Immunology or Microbiology for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Detection in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis

- 1. Department of Pediatrics, University Hospital “Aleksandrovska”, Bulgaria

- 2. Department of Clinical Laboratory and Immunology, Medical University, Bulgaria

- 3. Faculty of Medicine Medical University, Bulgaria

- 4. Department of Medical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine Medical University, Bulgaria

Abstract

Infection with P. aeruginosa (PA) is a milestone in the natural course of Cystic Fibrosis (CF), since its presence is associated with worsening of lung function and is a significant predictor of mortality. Besides through microbiology culture of the bacteria, PA infection could be detected with the immune response of the microorganism.

For a 1-year period we analyzed retrospectively the data of 140 patients with CF (77 males and 63 females, aged from 0 up to 62 years). 91 patients covered the criteria for a chronic PA infection (65.4%). A serum test for antibodies against PA with ELISA-ready kit was done to the rest of the patients (49) and on a random principle to 15 of the chronically infected ones.

From the studied group in 25 patients (39.06%) PA was not identified in the microbiological sample but elevated antibody titer was found. Almost half of those patients (12) had titre levels corresponding to a chronic infection. For those patients additional microbiology tests were performed and antibiotic treatment for some was done by consultant decision. In the follow up (in the range of 3 to 12 months) in 8 patients ?? was identified in the sputum.

This serology method has not yet been routinely applied in Bulgaria where one of the highest rates of chronic PA colonization in CF patients in Europe is reported. Routine inclusion of the serological test in the management plan for these patients might reduce this negative trend, through early initiation of eradication antibiotic regimens.

Keywords

• Cystic fibrosis

• Pseudomonas aeruginosa

• Serology

• Microbiology culture

Citation

Petrova G, Perenovska P, Lesichkova S, Lazova S, Miteva D, et al. (2017) Immunology or Microbiology for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Detection in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis – Results from Bulgaria. J Chronic Dis Manag 2(3): 1017.

ABBREVIATIONS

CF: Cystic Fibrosis; CFTR: Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator; PA: Pseudomonas Aeruginosa; FEV1: Forced Expiratory Volume for 1 second; BMI: Body Mass Index; ELISA: Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay

INTRODUCTION

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most common life-threatening inherited genetic disorder in the Caucasian population [1,2]. It is caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. In Bulgaria one in every 25 persons carry the mutated recessive gene and more than 1 in 3000 live births suffer from CF [3]. By the 1930s: the life expectancy of a baby with CF was only a few months, while in the 1980s, most deaths from CF occurred in children and teenagers. Today with improved treatments, nearly 40 percent of the CF population is aged 18 and older, and according the most recent publications for a person with CF the median age of survival is nearly 37 years [1,2].

Cystic Fibrosis affects a number of organs in the body, as cycles of infection and inflammation lead to a progressive deterioration of lung function. As a result of the disturbance in the ion secretion, the periciliar fluid is significantly less, which prevents normal muco-ciliary transport and mediates chronic bacterial infection. As a result, there is chronic airway inflammation [4].

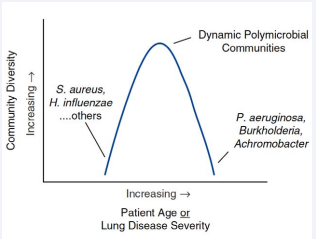

During the different age period there is airway bacterial diversity (Figure 1) [5].

Figure 1: Schematic representation of airway bacterial community diversity (number and abundance) versus patient age or lung disease severity (by Chmiel JF et al. Annal ATS 2014).

Initially there is an increase during childhood of gram-positive bacteria followed by glucose-non-fermenting gram-negative ones. The airway bacterial diversity peaks in young adulthood declines with advancing age and lung disease progression. At end-stage disease, bacterial communities may be dominated by a single species, most often a “typical” cystic fibrosis opportunistic pathogen [5].

Respiratory infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with CF [6-8]. The presence of PA in the lower airways is associated with a more rapid decline in pulmonary function, worsening of nutritional status, more hospital admissions, and a shorter life expectancy [9-11]. Patients with chronic PA infection are 2-3 times more at risk for fatal outcome in the subsequent eight years, compared to non-chronically infected patients [10,12]. It is known that chronic infection is preceded by intermittent colonization [13-17]. In some patients the colonization may persist for 1-2 years before initiating the immune response, due to the presence of transit non-pathogenic strains or due to an inadequate immune response of the microorganism [14,18]. The isolation of PA from sputum/ deep throat swab is not equal to presence of an infection unless the humoral response is available microorganism [17,19]. Once chronic infection with PA is established, it is almost impossible to eradicate it [20]. Eradication protocols for newly acquired PA were shown to eradicate PA in about 80% of the cases in both different randomized trials and in real-life studies [21,22]. Despite these data, based on genetic analysis of pathogens in patients with CF it was proven that in up to 70% of the successful “eradicated” cases, new colonization from the same genetic strain are found in future with the. This suggests for a possible delay of the infection [23].

Detecting PA in CF patients could be sometimes quite challenging. These patients in nearly 30-35% have difficulties in expectorating sputum (even after induction). By now we know that routine methods detect roughly 1% of bacterial pathogens in CF, another problem faced in these patients is the formation of biofilms by the bacteria and the biodiversity especially regarding Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) infection. (Figure 2) [24].

Figure 2: Different parts of the lung due to inhomogeneous changes provide different environment for the P. aeruginosa colonies, thus they grow with different nutritional requirements and antibiotic resistance. Therefore the therapy effective in some parts of the lung [25] (by J orth P, et al. Cell Host & Microbe 2015).

Besides microbiologic cultivation of the bacterium, the PA infection can be found through the immune response of macroorganism. Numerous studies on the detection of antibodies against PA by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) have proven missing or minimal interference of cross reacting antibodies against other bacteria. Levels of antibodies may serve as a marker for follow up – due to the proven higher levels in cases of mucoid phenotype, as well as to determine the type of infection-chronic or intermittent [25,36]. Such research is not done routinely in Bulgaria.

The purpose of this study is compare the results from serological and microbiological results in CF patients regarding the PA infection in attempt to explain the fact that relatively high number of CF patients in Bulgaria are treated with inhaled antibiotics for chronic infection with PA (57,55% of all CF patients and 70,79% of patients aged 6 years and over)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After obtaining a signed informed consent we included 140 patients with proven CF in Bulgaria (77 males and 63 females, aged from 0 to 62 years). Anthropometric data (height and weight) in all patients were measured with a calibrated balance and meter (Detectoscale, USA). Patients over 6.5 years of age performed functional study of the breathing with Masterscreen Pneumo spirometer ‘ 98 (Jager®, Wuerzburg, Germany), with drawing curves in real time and automatic correction (BTPS), in accordance with world standards by complying with the criteria for repeatability and reproducibility. From 3 ml venous blood, after the separation of serum antibody titre measurement was done through ELISA test kit ready (Pseudomonas-CF-Serum IgG, Statens Institut, Denmark) following a well-established methodology [27,28]. Sample from sputum/deep throat) swab was microbiologically tested for precise identification of gram - negative non fermenting microorganisms at the Department of medical microbiology, MU-Sofia, in accordance with international standards using BBL Crystal identification system (Becton Dickinson, USA) [17,29].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The initial patient characteristics are shown on Table 1.

Table 1: Patient’s characteristics.

| Males (n=77) | Females (n=63) | |

| Mean age in years ± SD (min-max) |

16.392 ±10.12 (0-42) |

19.310±12.08 (0-62) |

| FEV1 % mean ± SD (min-max) |

67,162±28.31 (1.75 - 128.54) |

66,018±25,617 (17.06 - 129.5) |

| BMI ZScore mean ± SD (min-max) |

-1.379±1.636 (-3.36 - +2.43) |

-1.4500±1.30519 (-4.1 - +2.28) |

| Chronic PA infection (yes:no) |

48:29 | 43:20 |

| Abbreviations: FEV1: Forced Expiratory Volume for 1 Second (The Best Value for the Year of Each Patient); BMI: Body Mass Index; SD: Standard Deviation | ||

For chronic PA infection were considered patients with 3 positive cultures for a period of 2 years. 91 covered these inclusion critheria (65.40% of all) – 66.6% of adults and 64.68% of children. These are the highest chronic PA data in Europe, the closes ones are those of Moldova (64.58%) and Greece (60%) for the children, while for the adults the closest numbers are reported in Macedonia and Sweden-59%. Fifteen of these chronically infected patients (on randomized principle) and all other patients (49) not meeting the criteria for chronic PA infection were included in the further immunological study. According the microbiological findings those 64 patients were divided in 3 groups:

1st group – without isolated ?? at the moment or at any other time before

2nd group – without isolated ?? at the moment, but with history with previous isolation

3rd group – with chronic ?? infection.

Table 2 covers the results of the patients in each group

Table 2: The results of the patients in each group and comparison between groups.

| Criteria | 1st group (n=15) | 2nd group (n=34) | 3rd group (n=15) | p, test |

| Age(mean± SD) | 14.42 ± 2.22 | 16.37 ± 2.4 | 15.2 ± 2.47 | 0.111, Kruskal-Wallis |

| Sex (m:f) | 8:7 | 18:16 | 7:8 | 0.96, Chi-square |

| Antibody titre (mean± SD; min-max) | 22.01 ± 17.43 (5.3-52) |

34.47 ± 19.59 (5.01-62) |

53.3 ± 3.9 (49.04-61.3) |

0.001, Kruskal-Wallis 0.000, ANOVA |

| FEV1%, (mean± SD; min-max )* | 86.22 ± 24.26 (36-120) |

81.45 ± 22.83 (40-120) |

66.30 ± 35.17 (14-119) |

0.253, Kruskal-Wallis 0.229, ANOVA |

| BMI, Z score (mean± SD; min-max)§ | -1.2 ± 0.9 (-2.87- +0.13) |

-0.37 ± 1.2 (-3.30 - + 1.2) |

-1.41 ± 1.27 (-3.27- +0.87) |

0.016, Kruskal-Wallis 0.030, ANOVA |

| Abbreviations: FEV1: Forced Expiratory Volume for 1 Second (The Best Value for the Year of Each Patient); BMI: Body Mass Index; SD: Standard Deviation *only for patients over the age of 7 (n = 56, 8 children did not perform spirometry - 2 from the first and third group and 4 from the second group) § only for patients over 2 years of age (under this age percentiles were defined, n = 63, only one child in group one is under 2 years of age) |

||||

In examining the specificity and sensitivity of the quantitative diagnostic test, we constructed Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves that graphically represent the relationship between sensitivity (indeed positive values) as a function of 1-specificity (false positives). The ROC curve shows the discriminatory power of the test using the area under curve (AUC). We counted the level of antibodies as a predictor for isolating PA from sputum / deep throat secretion.

For antibody titre below 25 U/ml (considered as an indicator for lack of any infection) AUC 0.337, p = 0.031, at a titer between 25 and 50 U/ml (considered as an indicator for intermittent infection) AUC 0.472, p = 0.749, at a titer above 50 U/ml (considered as an indicator for chronic infection) AUC 0.688, p = 0.014.

Corresponding analysis between the presence or absence of PA in the sputum and the interpretation of the antibody titer revealed a significant association (p = 0.002)

Our results suggest that there are some limitations to the microbiological culture study, which may not fully reflect the lung microbiome.

In a time where for CF patients PA and S. aureus are named the principle pathogens, and chronic infection is presumed as natural consequence of exposure, introduced once yearly prevalence reporting of pathogens provided a reasonable assessment of airway microbiology [1,2,29]. This assessment can serve as the basis for the efficiency of diagnosis and therapeutic measures applied. However, in the UK, when comparing different cohorts of children born with CF in 2008-2010 to the ones with CF born in the period 2011-2014 years completely unexpected for scientists was the discovery that the median age of first onset of PA is 10.8 months earlier for the later cohort. Such a comparison group, born between 1990-2001 and those between 2002-2014 proves that chronic infection with PA develops on average 6 years earlier in the second group [30]. One of the possible explanations for this fact is that modern children with CF get infected with PA earlier, leading to an earlier chronification. Another possible explanation is the earlier and reliable modern diagnosis when combining serological, microbiological and genetic approach.

A number of longitudinal studies prove the presence of high titre antibodies within 3 years prior to isolation in a culture of PA-i.e. antibody titre could be used as an early diagnostic marker for infection with PA [31].

It is possible that the titre of antibodies to be within the normal range (for uninfected or healthy person) just before the initial isolation, but in follow up it rises within 2 months [32]. The continued colonization in both cases leads to an increase in titre.

The presence of systemic immune response over the border of the norm is an indicator of tissue invasion and infection. At the same time the single isolation of PA, followed by a decline of the antibodies is a marker for an absence of infection [19,24,33]. In the presence of systemic corticosteroid treatment however, antibody titre is low, despite the presence of intermittent PA and thus it could not be used as a standalone biomarker [34].

In two patients, in which for the first time was isolated PA and high titre of antibodies an aggressive eradication therapy was performed. Positive results (drop in antibodies to the normal range, clinical improvement and negative microbiological results) were reported on the 6th month. For eradication it is considered lack of isolated microorganism and levels of antibodies within the normal low antibody titre (<25 U/ml) in the two patients is a good marker for a successful eradication, in accordance with the published literature [34,35].

In the all nine treated patients as expected clinical improvement was achieved, supported by serological testing, proving the applicability of the method in the follow-up plan. In one patient with observed negative trend and increased antibody titre, notwithstanding the absence of an isolated PA of sputum for the past 13 years, we also began antibiotic treatment according eradication protocol.

Many studies focus on the prolonged effect of aggressive treatment of infection with PA. They impose the need for the early initiation of inhaled antibiotic, in order to preserve the lung as long as possible, because the decline in the indicators of the functional testing of breathing is inevitable in the natural course of the disease [35,36].

PA remains the most frequent and significant pathogen for patients with CF. Its successful eradication is significant and economically an important objective for the treating CF team. Although difficult to be achieved, this task is attainable in accordance with the established protocols. In cases with eradication failure and thus chronification of the infection, the correct choice of antibiotic, the exact dosage and duration are associated with better quality of life and prolonged survival. It is important to note that the choice of antibiotic is at the discretion of the treating doctor in accordance with clinical and microbiological findings.

CONCLUSION

With this study, we have proven the good correlation between serology and microbiology as well as the possibility of early detection of potential infection and aggressive treatment prior to the actual microbiological isolation of PA. Similarly, to longitudinal studies our studies have shown the ability of serological tests to “spot” PA infection months before positive microbiological culture. This serology method has not yet been routinely applied in Bulgaria where there is one of the highest rates of chronic PA colonization in CF patients in Europe, probably due to the late PA confirmation and delayed eradication regimens. Timely and accurate detection of PA is crucial for therapy and prognosis. Routine inclusion of testing for antibodies against PA in the management plan for these patients might reduce this negative trend, through early initiation of eradication antibiotic regimens.

Our results confirm the role of antibodies as a useful marker for the progress of the infection and response to antibiotic treatment in patients with CF. Though still not universal approach; this is a step forward to the ideas of the microbiological and immunological phenomena, standing at the base of the infection with the PA in patients with CF.

The complex microbiology in CF requires the use of selective tools for atypical pathogens and specialized knowledge for:

a) Prevention, including avoiding cross-contamination,

b) Antibiotic therapy, including combinations, synergy tests, etc.,

c) Infections in the form of biofilm and chronicity of infections,

d) Side effects of antibiotics.

Such knowledge and skills can be acquired only through the close and long-term cooperation between doctors and the clinical microbiologist. Interdisciplinary teams should regularly discuss each patient and its diagnostic and therapeutic problems.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The study was carried out with the support of the Council for science, Medical University- Sofia (project No. 512/2016, grant No. 64/2016).

REFERENCES

1. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation National Patient Registry Annual Data Report. 2015.

2. European Cystic Fibrosis Society Patient Registry Annual Data Report 2015.

11. Temelkov A, Marinova R. Nosocomial infections in intensive care, Artik, Sofia. 2011(in Bulgarian).

12. O’Sullivan BP, Freedman SD. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 2009; 373: 1891- 1904.

![Different parts of the lung due to inhomogeneous changes provide different environment for the P. aeruginosa colonies, thus they grow with different nutritional requirements and antibiotic resistance. Therefore the therapy effective in some parts of the lung [25] (by J orth P, et al. Cell Host & Microbe 2015).](https://www.jscimedcentral.com/public/assets/images/uploads/image-1705650919-1.png )