The 4-Vinylcyclohexene Diepoxide (VCD)-Treated Rat Provides A Unique Preclinical Model to Study Peri-Menopausal Hot Flushes

- 1. Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, USA

- 2. Department of Physiology, University of Arizona, USA

Abstract

Objectives: Ovariectomy of young rodents is the most frequently used animal model of the menopause. However, the assumption that ovariectomy, causing a rapid loss of ovarian hormones is a general model of menopause in not well supported.

Several animal models have been developed with the aim of mitigating the human conditions of the menopause. Among these, the ovotoxin 4-vinylcyclohexene diepoxide (VCD) has gained popularity as chronic exposure to low dosing VCD causes apoptosis and subsequent ovarian follicle loss in rats and mice. The objective of these studies was to evaluate the VCD-treated female rat as a model of menopausal hot flush.

Methods: Fisher 344 rats were dosed daily with VCD (160 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle (sesame oil) for 20 days. By three months after the completion of VCD dosing all the animals showed vaginal cytology characteristic for constant diestrus indicating ovarian failure while control animals showed regular estrous cycles. At this point, control animals were ovariectomized. Four weeks later, all the animals were utilized in the morphine-addicted hot flush model.

Results: VCD-treated rats responded similarly to untreated ovariectomized rats, i.e., a 5-6C increase in their tail skin temperature (representing hot flush) was observed following morphine withdrawal. The tail skin temperature of ovariectomized, estrogen-treated rats increased only 2C following morphine withdrawal.

Conclusions: VCD-treated rats provide a more physiologically relevant model than young ovariectomized rats for studying menopausal symptoms, including hot flushes, since the gradual decrease in estrogen levels better mimics the human perimenopausal situation than ovariectomized animals (abrupt decline in estrogens)

Keywords

• Hot flush

• Menopause

• Ovariectomy

• Estrogen

Citation

Merchenthaler I, Lane MV, Zhan M, Hoyer PB (2014) The 4-Vinylcyclohexene Diepoxide (VCD)-Treated Rat Provides A Unique Preclinical Model to Study Peri-Menopausal Hot Flushes. J Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2(2): 1028.

INTRODUCTION

In female mammals, reproductive aging is characterized by a progressive decline in fertility attributed to the loss of follicles from the ovary and subsequent reduction in the serum levels of estrogens. The hypoestrogenic condition due to natural or surgical menopause results in dramatic changes in the function of estrogen-sensitive tissues in the periphery (pituitary, uterus, breast, bone) and the brain. These events are noted both in women and rodents.

Surgical menopause models only less than 13% of women (see the website http://www.menopause.org). The majority of women undergo natural menopause as a transitional hormone loss resulting from age-related alterations of the hypothalamus, pituitary, and ovary, ultimately resulting in follicular depletion and retention of residual ovarian tissue (1,2).

It is believed that neuronal changes in the hypothalamus initiate transition into reproductive decline early in the aging process, leading to reproductive senescence2 there are major differences in the mechanisms of age-related reproductive senescence of female rats and women. In women, as aging ensues, serum levels of estrogen and progesterone decline due to decreased ovarian follicular reserves (1). Thus, hormone loss during natural, nonsurgical menopause is ultimately due to ovarian follicle depletion. In contrast, the aging rat undergoes estropause, a persistent estrus state due to slightly elevated estrogen levels and chronic anovulation followed by a persistent diestrus state characterized by high progesterone levels due to increased activity of corpora lutea (3). These changes in ovarian-derived hormone release are primarily due to alterations in the hypothalamic/pituitary axis (3). Thus, the primary mechanism that ultimately results in reproductive senescence in the woman is ovarian follicle depletion, whereas in the rat it is the hypothalamic-pituitary axis.

The most common and characteristic symptom associated with the female climacteric is the hot flush which occurs in up to 75% of women after the physiological menopause or following oophorectomy (4-6). The critical role of estrogen in vasomotor instability resulting in hot flushes is supported by the known efficacy of estrogen therapy in preventing hot flushes. Although treatment of peri-and post-menopausal women with progestin, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs/NRIs), gabapentin, or clonidine shows minor efficacy, only estrogen or the combined estrogen/progestin therapy can prevent hot flushes effectively [7-12].

Although rodents do not flush after removal of the ovaries or when their estrous cycle ceases, a small elevation (0.3-0.5 C) of tail skin temperature (TST) can be detected in rats following ovariectomy (OVX) (13). A second, physiological model without any pharmacological manipulation is based on the undulating, diurnal changes in TST in intact female rats (14-15). These changes disappear following OVX but estrogen treatment restores them. However, circadian temperature changes are clearly not equivalent to episodic human menopausal symptoms. A third, frequently used model is a pharmacological model. This model utilizes OVX, morphine-dependent rats (16-20). There is ample evidence that morphine and endogenous opioids modify body temperature. Opioids are thought to participate by altering the hypothalamic set point for thermoregulation (21-23) although the precise mechanism of their action is not known. Furthermore, morphine-responsive temperature-sensitive neurons have been identified in the peptic area of the hypothalamus, which is a major site of temperature regulation (5). The same area contains many estrogen-sensitive neurons, however it is not known if these neurons are also responsive for temperature changes. When morphine effects in morphine-dependent rats are removed with the nonspecific opioid receptor antagonist naloxone, a 4-7 C increase can be seen in TST and this elevation can be reduced significantly with estrogens (17-19), clonidine (24), or SSRs/ NRIs (15). The amplification of changes in TST has made this model attractive for studies aimed at developing novel therapies for hot flushes (19).

The studies utilizing any of these rodent models of hot flush involved young OVX rats, although it remains to be determined if young, OVX animals do indeed provide a good model for menopausal human health conditions (25-28). However, reproductive aging can be facilitated pharmacologically, for example by repeated daily dosing with 4-vinylcyclohexene diepoxide (VCD) which causes loss of primordial follicles in rats and mice (29). Following repeated daily dosing with VCD, the animals are follicle-depleted but retain residual ovarian tissue (30). VCD-treated follicle-depleted rodents cease to cycle and plasma FSH, and to a lesser extent LH levels, increase (30-31). This is a profile resembling natural, non-surgically menopausal women. Due to absence of non-ovarian side effects, studies have used the VCD-induced transitional ovarian-failure model to investigate disease progression in cardiovascular, osteoporosis, diabetes and learning/memory rodent models (32-35).

The aim of the present studies was to compare the effect of morphine withdrawal on TST rise, representing hot flush, in morphine-dependent, surgically OVX and VCD-treated rats. We hypothesized that both treatments will result in elevated TSTs, reinforcing the critical role of estrogens in the pathomechanism of hot flushes. However, the gradual reduction of estrogens in the VCD model will make this model more attractive for future studies aimed at dissecting out the mechanism of hot flushes and developing/testing novel therapies.

METHODS

Animals and treatments

The research animals were housed in a facility accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The animals were used in accordance with NIH guidelines according to the policies of the University of Arizona Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Fisher 344 rats were dosed daily with VCD (160 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle (sesame oil) for 20 days. Vaginal cytology was monitored daily. By three months after the completion of VCD dosing all the animals showed constant diestrus indicating ovarian failure, while control animals showed regular estrous cycles. At this point, age-matched control animals were ovariectomized and four weeks later half of them were treated with ethynyl-estradiol (EE, 200 ug/kg, sc) for ten days. Our previous work has shown that chronic treatment with EE is necessary to reduce the tail skin temperature elevation (see below) (18).

Hot flush protocol

VCD-treated (experimental group), OVX (negative control group), or OVX-EE-treated (positive control group) rats were subcutaneously implanted with a morphine pellet containing 75 mg morphine sulfate (Murty Pharmaceuticals, Lexington, KY). Each group consisted of 10 animals (due to the limited number of animals, VCD-EE-treated group could not be included in the studies). Two days later, two additional morphine pellets were implanted similarly. On the eighth day, the animals were injected with Ketamine (80 mg/kg, im) and a thermocouple, connected to a Data Acquisition System (iWorx, Dove, NH), was taped on the tail approximately one inch from the root of the tail. This system allowed the continuous measurement of tail skin temperature. Baseline temperature was measured for 15 min, then naloxone (1.0 mg/kg) was given sc (0.2 ml) to block the effect of morphine and TST was measured for 40 minutes (19).

Statistical evaluation of results

The effect of morphine withdrawal-induced TST rise was demonstrated by measuring the area under the curve (AUC) and by measuring the differences in TSTs at ten minutes post-withdrawal time point when the changes are the largest (18).

The area under the curve or between the temperature change curve and the ground, from baseline to the end of measurement (about 40 minutes), was calculated by trapezoid formula. Specifically, we had temperature change values in every second, and the area in each time unit (second) was calculated, then all the areas were added up to get AUC for each rat. One factor ANOVA was performed to assess overall difference in AUC among the 3 groups, followed by using Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons to assess the differences between OVX+EE-treated and OVX+vehicle-treated groups, as well as between VCD-treated and OVX+vehicle-treated groups. In addition, one factor ANOVA and Dunnett’s test were applied to compare the temperature change at 10 minutes among the 3 groups. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., NC, and USA).

RESULTS

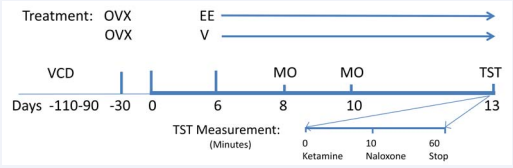

By three months after the completion of VCD dosing all the animals showed constant diestrus indicating ovarian failure, while control animals showed regular estrous cycles. At this point, control animals, with similar age as VCD-treated rats were ovariectomized and four weeks later half of them were treated daily with ethynyl-estradiol (EE, 200 ug.kg, sc) for ten days. Many of our studies have shown that this dose of EE consistently blunts the morphine withdrawal-induced rise in TST [15,18]. On day 11, the three groups of rats (OVX+vehicle; OVX+EE; and VCD) were exposed to the morphine-dependent rat hot flush model (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Protocol of the rat hot flush model. OVX or VCD-treated rats were made dependent to morphine by implanting a morphine pellet sc on days 3 and 5 of treatment. Two days after the second implantation, ketamine (80 mg/kg, im) was administered to keep calm the animals. Once they were calm, a thermistor, connected to a data acquisition system, was placed on the tail of the animals and morphine addiction was withdrawn by naloxone injection (1.0 mg/kg, sc). Temperature measurements were taken for 40-45 minutes.

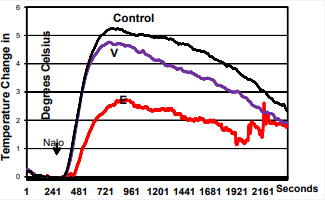

On average, the TST of OVX+vehicle-treated rats started to increase a few minutes after naloxone injection and reached the maximum value (app 5.5C) between 10-15 minutes. After this increase, TST started to drop and by 45 minutes it returned to the values close to those before naloxone administration or to TST values seen in EE-treated animals (Figure 2).

Figure 2 VCD and OVX animals respond similarly to morphine withdrawal indicating that the lack of estrogen in both models responsible for the rise in TST. In control animals, EE blunts the rise of TST in OVX rats. The data show TST changes during 45 minute evaluation time period. The difference in AUC between EE and control groups is significant (p<0.003), while the difference between VCD and control (OVX) groups is not significant (p<0.69).

Although TST values at 45 min post naloxone injection were still somewhat higher than those prior to naloxone injection, due to the fast metabolism of ketamine, at this point the animals become active and to prevent damaging the thermistors, we stopped the experiment.

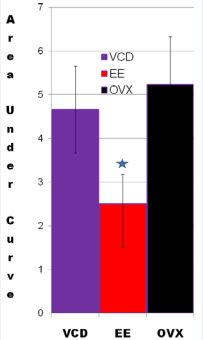

There were significant differences in temperature changes 10 minutes after naloxone administration among the 3 groups (P value for the overall F test is less than 0.001). The average temperature changes at 10 minutes were 5.25 (SE=0.40), 5.03 (SE=0.38), and 2.53 (SE=0.47), for OVX+vehicle-treated, VCD, and OVX+EE-treated groups, respectively. The difference in temperature changes at 10 minutes between OVX+EE and OVX+vehicle-treated groups was significant (P=0.0002), while the difference between VCD and OVX+vehicle-treated groups was not significant (P=0.89) (Figure 3).

Figure 3 VCD and OVX animals respond similarly to morphine withdrawal indicating that the lack of estrogen in both models responsible for the rise in TST. In control animals, EE blunts the rise of TST in OVX rats. The values of TST were taken at 10 minutes post-naloxone injection. The difference in temperature changes at 10 minutes between EE and control groups was significant (p<0.0002), while the difference between VCD and control groups was not significant (p<0.89).

There were also significant differences in AUCs among the 3 groups (P value for the overall F test is 0.004). The average AUCs from baseline to the end of measurement were 8221.90 (SE=808.09), 7407.56 (SE=773.69), and 3877.24 (SE=947.57), for OVX+vehicle, VCD, and OVX+EE groups respectively. The difference in AUC between OVX+EE and OVX+vehicle-treated groups was significant (P=0.003), while the difference between VCD and OVX+vehicle groups was not significant (P=0.69) (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

In women, the peri-menopausal period may last from a couple months to a few years during which the ovaries run out of developing follicles resulting in ovarian failure and diminished estrogen secretion (4). Hot flushes are characteristic features of the peri-menopause and menopause of primates (36). As millions of women suffer from menopausal symptoms (hot flushes, depression/anxiety, sleep disturbances, and dementia) a tremendous effort has been devoted to develop safer estrogen therapy, i.e., estrogen receptor ligands which could have beneficial effects in the brain, without stimulating the uterus and the breast. A major impediment to the development of safer alternatives, however, is the lack of animal model(s) that properly recapitulate the human symptoms (25-28).

As the volume and types of research that can be conducted directly in humans are extremely limited for ethical, practical, and financial reasons, we need to utilize animal models to better understand the complex biology and pathology of menopause. Animal species that experience similar menopausal processes as humans do is limited to non-human primates (NHPs). Only primates utilize both vasodilation and sweat responses for heat dissipation. Rodents utilize only radiant vasodilation as primary heat dissipation mechanisms. Thus, rodents do not accurately model the human hot-flush process but due to economic and technical problems, the use of NHPs is limited. Indeed, there have been only two studies utilizing small numbers of NHPs. Jelinek at al. (36) conducted a study utilizing two stumptail monkeys (Macaca arctoides) and Dierschke (37) rhesus monkeys (Macaca mullatta). Both showed that OVX induced an undulating pattern of skin temperature of the face and EE suppressed these changes. Similar undulating pattern of changes were observed in a menopausal monkey which was reversed with EE. The character and frequency of these changes resemble closely those recorded from women during hot flush stacks (4).

Although rodents do not flush following estrogen removal by OVX, it is believed that the central regulation of heat dissipation is similar among mammals. The observations that estrogens, SSRIs and NRIs, gabapentin, and clonidine reduces OVX-induced TST rise support this hypothesis (9-12). Most of the preclinical studies utilized OVX, morphine-dependent rats to study the mechanism of hot flushes and to test novel compounds for their efficacy (16-18,20). Among the many criticisms of this model, one is morphine treatment and the other is that the sudden drop in estrogen levels, as a result of OVX, does not mimic the situation occurring in premenopausal women. Therefore, the VCD-treated rat model provides a more relevant animal model to study the mechanism of hot flushes or other peri-menopausal symptoms including depression/anxiety, sleep disorders, dementia, learning and memory deficit, etc., since the gradual decrease in estrogen levels better mimics the pattern of hormonal changes present in human peri-menopausal conditions.

4-vinylcyclohexene diepoxide (VCD) is an occupational chemical and an active metabolite of the industrial byproduct 4-vinylcyclohexene. It has also been widely used as a solvent of other epoxides. VCD selectively destroys primordial and primary ovarian follicles in rats and mice with no significant effects on larger follicles or corpora lutea. Although has not been studied extensively, it is assumed that VCD does not affect significantly other systems in mice and rats (30,33,38). Only after weeks to months following repeated exposures to VCD and depletion of primordial follicles are there reductions of other follicle populations, reductions in uterine and ovarian weights, and cessation of cyclicity. These effects are assumed to be resulting from premature ovarian failure rather than from direct effects of VCD.

CONCLUSION

The primary purpose of these studies was to test the VCD-treated rats as a model of the human menopause. Our data clearly show that animals treated with VCD or ovariectomized, respond to morphine withdrawal with similar rise in TST, representing a flush. Due to the limited number of VCD-treated rats available, we did not include a VCD-estrogen-treated group. VCD-treated rats provide a more physiologically relevant model than young ovariectomized rats for studying menopausal symptoms, including hot flushes, since the gradual decrease in estrogen levels better mimics the human peri-menopausal situation than ovariectomized animals (abrupt decline in estrogens).

ETHICAL STANDARDS

We declare that the experiments comply with the current laws of the USA (NIH guidelines according to the policies of the University of Arizona Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Miss April Puskar for her valuable assistance. This work was Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Grant ES09246 (P.B.H.)

Funding/support

In part by ES09246 (Patricia B Hoyer)

REFERENCES

1. Timaras P, Quay W, Vernadakis A.eds. Hormones and Aging. New York, CRC Press, 1995.

4. Kronenberg F. Hot flashes: epidemiology and physiology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990; 592: 52-86.

11. Pitkin J. Alternative and complementary therapies for the menopause. Menopause Int. 2012; 18: 20-27.

25. Bellino FL, Wise PM. Nonhuman primate models of menopause workshop. Biol Reprod. 2003; 68: 1008.