Disruption of Cytokine Signaling Networks in Coronavirus Infection: from Immune Evasion to Cytokine Storm

- 1. School of Animal Science and Technology, Foshan University, China

- 2. Foshan University Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Foshan University, China

Abstract

Coronavirus infection elicits an immune response characterized by marked temporal phases and highly dynamic regulatory patterns, with the balance and subsequent disruption of cytokine signaling networks at its core. Through a diverse array of non-structural, structural, and accessory proteins, the virus rewires host immunity by suppressing interferon production, blocking JAK–STAT signalling, and activating NF-κB and MAPK pathways, thereby gaining a replicative advantage during the early stages of infection. A systematic delineation of the mechanisms underlying cytokine-signaling dysregulation will refine the immunopathological framework of coronavirus infection and inform more precise therapeutic strategies.

Keywords

• Cytokine-Signaling

• Coronavirus

• Immunopathogenesis

• Mechanistic

Citation

Sun Q, Liu Y, Zhang L, Chen J, Fu Q (2025) Disruption of Cytokine Signaling Networks in Coronavirus Infection: from Immune Evasion to Cytokine Storm. J Immunol Clin Res 8(2): 1058.

INTRODUCTION

The family Coronaviridae, belonging to the order Nidovirales, comprises enveloped, single-stranded positive-sense RNA viruses and represents one of the RNA virus groups with the largest genomes. According to the latest report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV, 2023), this family contains a single subfamily, Orthocoronavirinae, which is further divided into four genera: α-, β-, γ-, and δ-coronaviruses. The first two predominantly infect mammals and include all known human coronaviruses, whereas γ- and δ-coronaviruses mainly circulate in avian hosts [1].

Coronaviruses can cause a spectrum of acute respiratory infections, including upper respiratory tract illness, bronchitis, and pneumonia, and may also trigger gastrointestinal manifestations such as reduced appetite, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea [2]. In addition, emerging evidence indicates that coronaviruses are associated with a range of central nervous system disorders, including neuroinvasive infections, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and multiple sclerosis [3].

The host immune response serves as both a protective barrier and a source of tissue injury during viral infection. Throughout coronavirus infection, the virus and host immune system engage in a complex and dynamic interplay: on the one hand, interferon pathways and pro inflammatory signaling are activated to establish antiviral defense; on the other, multiple viral proteins target and disrupt the homeostatic regulation of host cytokine networks. Immune-signaling imbalance during the early infection phase and the progression to severe disease represents a critical determinant of clinical outcomes. By blocking the JAK–STAT pathway, suppressing NF κB activation, or aberrantly activating MAPK signaling, coronaviruses impair the proper integration of cytokine responses—simultaneously weakening antiviral defenses and amplifying inflammatory cascades—ultimately facilitating immune evasion and precipitating systemic cytokine storm.

This review aims to systematically delineate the dynamic regulation and dysregulation of cytokine signaling networks during coronavirus infection. By integrating perspectives on the immunomodulatory functions of viral proteins, the crosstalk among core immune signaling pathways, the amplification routes of inflammatory responses, and the pivotal stages of immune paralysis and tissue repair, it constructs a comprehensive framework of virus–host immune interactions. Such a framework provides a mechanistic foundation for understanding the pathogenesis of severe disease and supports the development of targeted immunotherapeutic strategies.

VIRAL PROTEIN–MEDIATED REWIRING OF HOST SIGNALING NETWORKS

Coronaviruses are enveloped, positive-sense RNA viruses with genomes of approximately 30 kb. The 5′-proximal two-thirds of the genome contain ORF1a/1b, which are translated into the large polyproteins pp1a/ pp1ab and subsequently cleaved into non-structural proteins NSP1–16. The 3′-terminal one-third encodes the structural proteins S, E, M, and N, along with a set of accessory proteins whose composition varies across viral subgenera [4].

Non-structural Proteins

Non-Structural Proteins (NSPs), encoded by the viral ORF1ab region and generated through proteolytic processing, primarily participate in viral replication transcription and immune evasion, and several serve as key antiviral drug targets. All coronaviruses encode NSP1–16, though NSP1 may be absent or truncated in some avian γ- and δ-coronaviruses. NSP1 occludes the ribosomal mRNA entry channel to suppress host translation and prioritize viral protein synthesis. NSP3 contains a papain-like protease domain responsible for autoprocessing, deubiquitination, and broad immune antagonism [5]. NSP4 and NSP6 act in concert with NSP3 to induce the formation of double-membrane vesicles that serve as replication platforms. NSP5, the main protease, executes extensive polyprotein cleavage and constitutes a key target for antiviral drug development [6]. NSP7, NSP8, and NSP12 assemble into the polymerase complex that carries out viral RNA synthesis [7]. NSP13 possesses helicase and NTPase activities that advance the replication fork and support the viral replication–transcription process [8]. NSP14 combines exonuclease and methyltransferase activities to provide proofreading and RNA capping, thereby maintaining genomic stability [9]. NSP15 employs its endoribonuclease activity to degrade immunogenic double-stranded RNA, thereby reducing its visibility to host immune sensors [10]. NSP16 forms a 2′-O-methyltransferase complex with NSP10 to modify the viral RNA cap and evade recognition by IFIT proteins. Together, these components assemble the viral replication factory and reprogram host metabolic pathways [4].

Accessory Proteins

ORF3a modulates lysosomal exocytosis and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome [11]. ORF3b, a short accessory protein of coronaviruses, inhibits the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of IRF3 in SARS-CoV by binding to IRF3, thereby blocking the RIG-I/MAVS–TBK1–IRF3 axis and markedly reducing IFN-β promoter activity [12]. Its sequence is highly variable, and extended ORF3b variants identified in SARS-CoV-2 lineages exhibit stronger type I interferon suppression [13]. ORF6 binds components of the nuclear pore complex to block the nuclear entry of STAT1 and IRF3, thereby attenuating interferon signaling [14]. ORF8 associates with MHC-I and promotes its degradation, diminishing antigen presentation [15]. Although accessory proteins are not directly required for replication, they profoundly shape immune evasion and pathogenicity.

Structural Proteins

Coronaviruses encode four essential structural proteins with distinct functional roles. The spike (S) protein is a trimeric class I membrane glycoprotein whose S1 subunit contains the receptor-binding domain and whose S2 subunit includes the fusion peptide and transmembrane region. Upon receptor engagement, host proteases cleave S to trigger membrane fusion, making it a key determinant of tissue tropism and transmissibility [16]. Studies further indicate that the co-receptor NRP1 enhances S-mediated attachment and entry efficiency [17]. The membrane (M) protein, the most abundant structural component, is a triple-pass transmembrane protein that governs virion assembly and membrane curvature. Within the ERGIC, it orchestrates the incorporation of S, E, and N proteins to form mature virions [18]. The envelope (E) protein is a small viroporin that modulates vesicular pH and viral egress, and its ion-channel activity directly influences host inflammatory responses and viral pathogenicity [19]. The nucleocapsid (N) protein binds viral RNA to form the ribonucleoprotein complex, stabilizes the replication transcription machinery, supports subgenomic RNA (sgRNA) synthesis, and interacts with host signaling factors to suppress antiviral pathways [20].

OVERALL CHARACTERISTICS OF CYTOKINE RESPONSES DURING CORONAVIRUS INFECTION

Following coronavirus infection, the host immune system releases cytokines in a highly ordered, temporally dynamic manner. This process can be broadly divided into four phases: the antiviral interferon phase, the hyperinflammatory phase, the immunoparalysis phase, and the tissue-repair phase.

Antiviral Interferon Phase

Coronaviruses such as SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 trigger a characteristic early innate immune response in which viral RNA sensing rapidly induces type I and type III interferon production, establishing an IFN ISG–dominated antiviral state.

Type I interferons (IFN-α/β), produced primarily by infected epithelial cells and dendritic cells, activate the JAK–STAT pathway to drive the expression of interferon stimulated genes (ISGs), thereby restricting viral RNA replication, protein translation, and virion assembly [21]. Type III interferons (IFN-λ), mainly secreted by mucosal epithelial cells, exert localized antiviral protection confined to epithelial surfaces, reducing the risk of systemic inflammation; during respiratory infection, IFN-λ is induced earlier than IFN-α/β and exhibits a more sustained effect [22]. Concurrently, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α are released by infected epithelial cells and macrophages, initiating acute-phase responses and promoting immune-cell recruitment [23]. Chemokines including CCL2, CXCL10, and CXCL9 further recruit monocytes, NK cells, and T cells, creating a tightly intertwined and cooperative antiviral inflammatory network [23]. This phase is characterized by delayed interferon induction alongside gradually rising inflammatory mediators: low early IFN-I/III levels permit rapid viral replication, whereas subsequent interferon upregulation suppresses viral expansion; incomplete viral control, however, may transition the response into an IL-6– and CXCL10-dominated inflammatory-amplification stage. The objective of this phase is to limit viral replication, set the inflammatory threshold, and coordinate the initiation of adaptive immunity.

Hyperinflammatory Phase

The hyperinflammatory phase represents the transition from antiviral defense to immune-mediated injury during coronavirus infection. This stage is marked by waning interferon-mediated antiviral activity and persistent amplification of inflammatory signaling. Its core mechanism involves prolonged innate immune activation with failure of negative-feedback control, leading monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils to continuously release pro-inflammatory cytokines that drive tissue damage and coagulopathy. During this period, immune activity no longer centers on viral clearance but instead becomes dominated by escalating inflammatory cascades [24]. In the early phase, viral suppression of IFN-I and IFN-III pathways weakens the IFN–ISG axis, prompting excessive compensatory activation of NF-κB, JAK–STAT, and NLRP3 inflammasome signaling in the host [25]. Persistent recognition of residual viral RNA or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) by pattern-recognition receptors activates IRF3 and NF-κB, inducing high level secretion of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, CXCL10, and other mediators that fuel the cytokine storm [25]. Continued cytokine stimulation sets up a self-reinforcing positive feedback loop, sustaining and escalating inflammation. The outcomes of this phase—tissue injury, immunothrombosis, and multiorgan dysfunction—reflect a pathological shift from antiviral immunity to immune-driven damage.

Immunoparalysis and Tissue-Repair Phase

Following the hyperinflammatory phase, the host enters a period of downregulated defense capacity and effector cell exhaustion—referred to as the immunoparalysis phase. During this stage, monocytes and macrophages exhibit reduced expression of HLA-DR and costimulatory molecules, leading to impaired antigen presentation [26]. T cells, subjected to persistent antigen exposure and an inflammatory milieu, upregulate inhibitory receptors such as PD-1 and TIM-3 and undergo functional exhaustion [27]. Elevated IL-10 and TGF-β further suppress inflammatory signaling and dampen effector-cell activation. As a result, the host becomes prone to secondary infections, and both antiviral activity and tissue-repair efficiency decline [26]. The subsequent repair phase represents an active process in which the immune system resolves inflammation and restores tissue integrity. This stage is characterized by the production of specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs)—including resolvins, protectins, and maresins— and the polarization of inflammatory M1 macrophages toward reparative M2 phenotypes. These processes promote apoptotic-cell clearance and facilitate the restoration of vascular and epithelial barriers [28].

MAJOR CYTOKINE SIGNALING PATHWAYS AND THEIR DYSREGULATION IN CORONAVIRUS INFECTION

The JAK–STAT Pathway

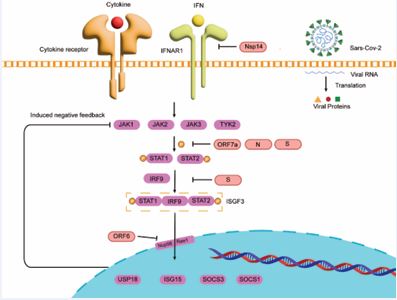

The JAK–STAT pathway serves as a central regulatory hub of immune homeostasis, rapidly linking extracellular cytokine signals to intracellular transcriptional programs that coordinate antimicrobial defense, tissue repair, and metabolic balance. Upon ligand engagement with class II cytokine receptors, members of the JAK family become activated, phosphorylating tyrosine residues on receptor tails and recruiting STAT proteins, which dimerize upon phosphorylation and translocate into the nucleus to regulate target genes [29]. STAT dimers bind GAS or ISRE elements to drive the expression of inflammatory mediators, antiviral effectors, and growth-related genes [30]. Negative regulators—including SOCS proteins, PIAS proteins, and tyrosine phosphatases—constitute feedback systems that constrain signal amplitude and duration [31,32]. Through JAK–STAT activation, interferons induce ISG expression and establish a broad antiviral state; IFN-γ STAT1 activation enhances macrophage microbicidal activity, antigen presentation, and class I MHC expression. Coronaviruses suppress the JAK–STAT pathway through multiple converging mechanisms to gain a replicative advantage during early infection. They delay interferon induction, weaken JAK–STAT activation, and deploy individual viral proteins to directly disrupt signal transduction [33,34]. In SARS-CoV-2, ORF6 binds the interferon-inducible Nup98–Rae1 complex and sequesters it away from the nuclear pore, thereby blocking nucleocytoplasmic transport and preventing STAT1/STAT2 nuclear entry [14-29]. ORF7a inhibits ISGF3 nuclear translocation and selectively suppresses IFN-α–induced STAT2 phosphorylation; it also interacts with HNRNPA2B1 to dampen IFN-triggered JAK STAT signaling [35]. NSP1 binds the ribosome to induce host-mRNA translation shutoff, reducing the protein levels of key signaling factors such as TYK2 and STAT2 and broadly impairing IFN-induced JAK–STAT responses [36]. PLpro suppresses host translation and ISG induction, preventing the onset of an antiviral state [34]. Recent studies show that NSP14 downregulates or degrades IFNAR1, thereby blocking IFN-α/β–mediated JAK–STAT activation and downstream ISG expression [37].

The spike protein (S) activates the angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) cascade, which stimulates MAPK signaling and activates NF-κB and AP-1/c-Fos, leading to IL-6 upregulation and STAT3-driven inflammation that creates a microenvironment favorable for viral replication [38]. Additional evidence indicates that S protein can compete with STAT2 for IRF9 binding, preventing assembly of the classical ISGF3 (STAT1–STAT2–IRF9) complex and thereby blocking ISG transcription [39]. The N protein suppresses STAT1/STAT2 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation, further reducing ISG induction [40]. The E protein modulates ER stress, inflammation, and virion assembly, exerting indirect effects on JAK–STAT signaling [34]. The M protein interacts with MDA5, TRAF3, TBK1, and IKKε, promoting K48-linked ubiquitination and degradation of TBK1, thereby inhibiting IRF3 activation and IFN-β production [41] [Figure 1]. Together, these mechanisms delay interferon responses, block STAT nuclear entry, and reconfigure host transcriptional and metabolic programs, enabling the virus to complete several replication cycles before host defenses are fully engaged.

NF-κB Pathway

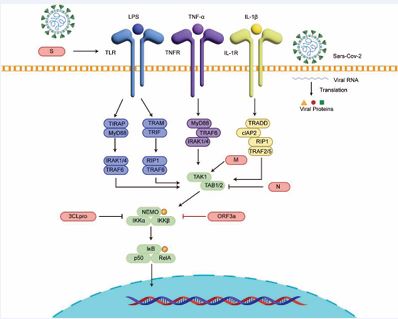

The canonical NF-κB signaling pathway is activated by receptors such as BCR, TCR, TLRs, IL-1R, and TNFR. Upstream stimulation activates the CBM complex or the TAK1–TAB module, which subsequently phosphorylates and activates the IKK complex. Activated IKK promotes the degradation of the inhibitor IκBα, thereby releasing the NF-κB p50/RelA heterodimer [42,43]. NF-κB then translocates into the nucleus, binds κB elements, and induces transcription of inflammatory genes such as TNF and IL-6, ultimately initiating JAK–STAT and MAPK cascades as well as inflammasome activation, thus driving inflammatory and acute-phase responses [42-44]. The coronavirus S protein can be sensed by TLR2 or TLR4, leading to NF-κB activation and increased expression of TNF, IL-6, pro–IL-1β, and various chemokines [45]. For example, SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 S proteins are recognized by TLR2 and activate NF-κB signaling [45], whereas PDCoV S protein activates NF-κB via TLR4 [46]. The E protein, one of the most conserved inflammatory activators across the coronavirus family, induces Ca²? efflux and ER stress, thereby activating NF-κB signaling and upregulating inflammatory mediators. In SARS-CoV-1, the E protein forms Ca²? channels in the ERGIC membrane, promoting Ca²? release, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and IL-1β maturation; viruses lacking E protein fail to effectively activate NF-κB [47,48]. SARS-CoV-2 N protein can inhibit the TAK1–TAB2/3 complex and thereby block NF-κB activation [49]. ORF3a interacts with IKKβ/NEMO to enhance NF-κB activation [50] [Figure 2]. Structural and biochemical evidence further shows that SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro cleaves NEMO, an essential subunit of IKK, thereby disrupting the assembly of NF-κB and interferon signaling complexes. This activity contributes to immune evasion and is implicated in endothelial and neurological damage associated with infection [51]. PLpro removes K63-linked ubiquitin and ISGylation (ISG15) from key adaptor proteins in the RLR and TLR pathways, broadly suppressing IFN and NF-κB signaling initiation. However, NF-κB can still be maintained through alternative routes, resulting in an imbalanced state characterized by high inflammation but low interferon responses [52-54].

MAPK Pathway

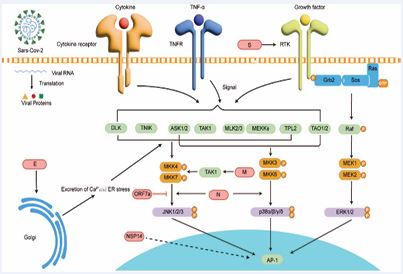

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is a central intracellular signaling cascade that conveys extracellular cues to the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. Its core functions include the fine-tuned regulation of gene expression, cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and inflammatory responses. MAPK signaling operates through a canonical tiered kinase cascade and consists of three major branches: ERK1/2, JNK, and p38.

Figure 1 Coronavirus proteins targeting the JAK–STAT signaling pathway | ORF7a, N protein, and the S protein selectively inhibit STAT2 phosphorylation; the S protein can block ISGF3 assembly; ORF6 binds the Nup98–Rae1 complex to prevent nuclear entry of the ISGF3 complex.

These branches exhibit extensive cooperative and antagonistic interactions and are frequently co-activated during complex conditions such as viral infection.The ERK1/2 pathway primarily responds to growth factors and is initiated through the Raf–MEK–ERK phosphorylation cascade, regulating cell proliferation and differentiation. Activated ERK translocates into the nucleus or acts on cytoplasmic substrates [55]. In contrast, the JNK and p38 pathways constitute major stress-responsive and immunoregulatory axes. JNK signaling is triggered by oxidative stress, TNF, IL-1, and viral infection [56], driving phosphorylation of transcription factors such as c-Jun and ATF2 and contributing to apoptosis and pro-inflammatory gene expression [57]. The p38 pathway is activated by inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF, IL-1) and TLR-mediated pathogen-recognition signals [58]. As a key regulatory hub, p38 controls the transcription, translation, and mRNA stability of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and IL-6 and plays essential roles in immune responses, stress tolerance, and programmed cell death [59].

Figure 2 Coronavirus proteins targeting the NF-κB signaling pathway | ORF3a enhances NF-κB activation by interacting with IKKβ/NEMO; 3CLpro cleaves NEMO, an essential subunit of the IKK complex, facilitating viral immune evasion; the N protein suppresses the TAK1–TAB2/3 complex and thereby blocks NF-κB activation.

Upon binding to ACE2, the coronavirus S protein can cross-activate the EGFR–RAF–MEK–ERK axis, inducing ERK1/2 phosphorylation to enhance metabolic activity and protein synthesis, thereby supplying energy and biosynthetic capacity for viral replication while increasing cellular secretion and survival [60,61]. Meanwhile, S protein and other structural proteins such as E protein are recognized by TLR2/MyD88, triggering p38 and JNK activation and promoting AP-1– and NF-κB-mediated transcription of pro-inflammatory genes, leading to high-level production of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β [45-62]. Reviews also report that the CoV M protein modulates the TRAF–TAK1 complex, linking it to p38 and JNK activation and inflammation [63,64]. The coronavirus E protein induces Ca²? efflux and ER stress, thereby activating ASK1–MKK3/6–p38 and ASK1–MKK4/7–JNK cascades [65]. SARS-CoV N protein has been shown to induce apoptosis through JNK and p38 pathways [64]. Recent studies indicate that SARS CoV-2 Nsp14 significantly enhances AP-1 reporter activity [66]. Additional evidence suggests that accessory proteins ORF3a and ORF7a activate p38 and JNK, linking them to mitochondrial stress and enhanced apoptosis/ inflammation, and may amplify antiviral responses [67]. SARS-CoV ORF7a has also been reported to promote JNK1 phosphorylation and cooperate with NF-κB to induce IL-8 and CCL5 expression [68-71] [Figure 3].

Figure 3 Coronavirus proteins targeting the MAPK signalling pathway | ORF7a enhances JNK1 phosphorylation; Nsp14 increases AP-1 reporter activity through the canonical p38/JNK/ERK pathways.

Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Cytokine Signaling

Given the dynamic immune landscape in coronavirus infection—characterized by a transition from antiviral defense to excessive inflammation—current therapeutic strategies emphasize temporally precise modulation of cytokine signaling. Interferon (IFN)-based agents are employed in the early phase to enhance innate antiviral immunity, whereas anti-inflammatory biologics and signaling-pathway inhibitors are implemented during the middle and late stages to restrain pathological inflammation.

Interferon Therapy and Timing of Administration

Both type III IFN (IFN-λ) and type I IFNs (IFN-α/β) exert antiviral effects by inducing ISG expression; however, IFN-λ receptors are restricted to epithelial barriers, allowing potent local activity with fewer systemic adverse effects [72]. The optimal therapeutic window is within the first three days of symptom onset, during which a single subcutaneous dose of PEG-IFN-λ significantly reduces the risk of hospitalization or prolonged emergency visits in high-risk patients with mild to moderate disease. Its efficacy extends across viral variants and combines antiviral activity with anti-inflammatory potential [72]. Clinically, IFN-λ is prioritized for patients in the early symptomatic phase without evidence of systemic inflammation, with the greatest benefits observed in high-risk populations. It should not be administered once oxygen support becomes necessary or when CRP levels rise, indicating systemic inflammation. Use of type I IFNs during the inflammatory phase requires caution, and guideline recommendations continue to evolve [73].

Anti-inflammatory Biologics and Signaling-Pathway Inhibitors

During the intermediate phase of viral infection, therapeutic strategies pivot toward anti-inflammatory intervention, employing biologics and signaling-pathway inhibitors to interrupt the cytokine-amplification cascade. Glucocorticoids, particularly dexamethasone, suppress NF-κB and AP-1 signaling and reduce IL-6 and TNF production. They are first-line therapy for hypoxic severe cases and significantly lower 28-day mortality, whereas their use provides no benefit in non-hypoxic patients [74]. IL-6R blockade disrupts the IL-6–JAK STAT3 inflammatory-amplification loop; in patients with systemic inflammation requiring oxygen therapy, IL-6R inhibitors combined with corticosteroids reduce both mortality and progression to critical illness [75]. IL-1 receptor antagonism with anakinra inhibits the IL-1β driven NLRP3–NF-κB axis. When stratified using soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) levels ≥6 ng/mL, early initiation of anakinra reduces the risk of respiratory failure and death [76].

As a downstream convergence node for multiple pro inflammatory cytokines, the JAK–STAT pathway is an attractive target for broad-spectrum immunomodulation. Baricitinib, a JAK inhibitor, suppresses IL-6, IFN-γ, GM CSF, and related signaling axes. In the ACTT-2 trial, its combination with remdesivir shortened recovery time and improved clinical status among hospitalized patients [77]. Rigorous safety monitoring is essential during treatment. Key considerations include secondary infections, hepatic injury, hematologic abnormalities, thrombotic and cardiovascular events, and screening for latent tuberculosis and hepatitis B reactivation [78]. According to WHO 2025, IDSA, and NICE guidelines, corticosteroids constitute the foundation of therapy for severe disease, upon which a single immunomodulatory agent should be selected [73].

CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVES

During coronavirus infection, the JAK–STAT, NF-κB, MAPK, and NLRP3 pathways constitute a continuous immunological axis. Early in infection, interferon induced JAK–STAT signaling initiates antiviral defense and suppresses viral replication. Upon recognition of viral RNA, NF-κB and MAPK pathways are activated and drive the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6. IL-6 amplifies inflammation through a JAK–STAT3–mediated positive-feedback loop, while TNF-α concurrently activates NF-κB and MAPK to further intensify inflammatory output. The precursor of IL-1β is generated through NF-κB signaling and processed to its mature form via NLRP3 inflammasome activation, triggering pyroptosis and additional cytokine release. These four pathways are interconnected through IL 6, TNF-α, and IL-1β as central nodes, linking antiviral responses with inflammatory escalation. Together, they illustrate the host’s dynamic transition from antiviral containment to immune dysregulation and delineate a unified model of signal transduction, inflammatory regulation, and tissue injury.

Despite progress, current research still lacks precise mapping of how specific structural domains of S and N proteins remodel innate-immune “dose–timing–spatial” effects across viral variants and host cell types, leaving a gap between molecular sites and phenotypic outcomes [79]. Immunomodulatory therapies are often administered based on empirical staging, with few validated quantitative biomarker thresholds [80]. The therapeutic window for early innate-immune enhancers such as IFN-λ, as well as their optimal sequencing with small-molecule antivirals and later anti-inflammatory agents, remains insufficiently defined due to limited prospective evidence [81]. Precision modulation of cytokine signaling is expected to become a major direction in future therapeutic strategies against coronavirus-associated diseases.

REFERENCES

- Woo PCY, de Groot RJ, Haagmans B, Lau SKP, Neuman BW, Perlman S, et al. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Coronaviridae 2023. J Gen Virol. 2023; 104: 001843.

- Luo X, Zhou G Z, Zhang Y. Coronaviruses and gastrointestinal diseases. Military Medical Research, 2020; 7: 49.

- ???????????????????????????_???[Z].

- V’kovski P, Kratzel A, Steiner S, Stalder H, Thiel V. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021; 19: 155-170.

- Schubert K, Karousis ED, Jomaa A, Scaiola A, Echeverria B, Gurzeler LA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp1 binds the ribosomal mRNA channel to inhibit translation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2020; 27: 959-966.

- Huang Y, Wang T, Zhong L, Zhang W, Zhang Y, Yu X, et al. Molecular architecture of coronavirus double-membrane vesicle pore complex. Nature. 2024; 633: 224-231.

- Hillen HS, Kokic G, Farnung L, Dienemann C, Tegunov D, Cramer P. Structure of replicating SARS-CoV-2 polymerase. Nature. 2020; 584: 154-156.

- Newman JA, Douangamath A, Yadzani S, Yosaatmadja Y, Aimon A, Brandão-Neto J, et al. Structure, mechanism and crystallographic fragment screening of the SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 helicase. Nat Commun. 2021; 12: 4848.

- Eckerle LD, Becker MM, Halpin RA, Li K, Venter E, Lu X, et al. PLoS Pathog. 2010; 6: e1000896.

- Kindler E, Gil-Cruz C, Spanier J, Li Y, Wilhelm J, Rabouw HH, et al. Early endonuclease-mediated evasion of RNA sensing ensures efficient coronavirus replication. PLoS Pathog. 2017; 13: e1006195.

- Chen D, Zheng Q, Sun L, Ji M, Li Y, Deng H, et al. ORF3a of SARS-CoV-2 promotes lysosomal exocytosis-mediated viral egress. Dev Cell. 2021; 56: 3250-3263.e5.

- Kopecky-Bromberg SA, Martínez-Sobrido L, Frieman M, Baric RA, Palese P. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus open reading frame (ORF) 3b, ORF 6, and nucleocapsid proteins function as interferon antagonists. J Virol. 2007; 81: 548-57.

- Konno Y, Kimura I, Uriu K, Fukushi M, Irie T, Koyanagi Y, et al. Cell Rep. 2020; 32: 108185.

- Miorin L, Kehrer T, Sanchez-Aparicio MT, Zhang K, Cohen P. SARS- CoV-2 Orf6 hijacks Nup98 to block STAT nuclear import and antagonize interferon signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020; 117: 28344-28354.

- Zhang Y, Chen Y, Li Y, Huang F, Luo B, Yuan Y, et al. The ORF8 protein of SARS-CoV-2 mediates immune evasion through down-regulating MHC-Ι. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 ;118: e2024202118.

- Lan J, Ge J, Yu J, Shan S, Zhou H, Fan S, et al. Structure of the SARS- CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020; 581: 215-220.

- Cantuti-Castelvetri L, Ojha R, Pedro LD, Djannatian M, Franz J, Kuivanen S, et al. Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and infectivity. Science. 2020; 370: 856-860.

- Gorkhali R, Koirala P, Rijal S, Mainali A, Baral A, Bhattarai HK. Structure and Function of Major SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV Proteins. Bioinform Biol Insights. 2021; 15: 11779322211025876.

- Schoeman D, Fielding BC. Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Virol J. 2019 ;16: 69.

- Wu W, Cheng Y, Zhou H, Sun C, Zhang S. The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein: its role in the viral life cycle, structure and functions, and use as a potential target in the development of vaccines and diagnostics. Virol J. 2023; 20: 6.

- Allaf B, Pondarre C, Allali S, De Montalembert M, Arnaud C, Barrey C, et al. Appropriate thresholds for accurate screening for β-thalassemias in the newborn period: results from a French center for newborn screening. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020; 59: 209-216.

- Khurana S, Chen KK, Brooks JJ. Radiographic Outcomes in Treatment of Thumb Basal Joint Arthritis: Does Interposition of Acellular Dermal Allograft Prevent Metacarpal Settling? J Hand Microsurg. 2020; 12: 177-182.

- Flint RB, Simons SHP, Andriessen P, Liem KD, Degraeuwe PLJ, Reiss IKM, et al. The bioavailability and maturing clearance of doxapram in preterm infants. Pediatr Res. 2021; 89: 1268-1277.

- Hadjadj J, Yatim N, Barnabei L, Corneau A, Boussier J, Smith N, et al. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID-19 patients. Science. 2020; 369: 718-724.

- Del Valle DM, Kim-Schulze S, Huang HH, Beckmann ND, Nirenberg S, Wang B, et al. An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID-19 severity and survival. Nat Med. 2020; 26: 1636-1643.

- Hammad R, Kotb HG, Eldesoky GA, Mosaad AM, El-Nasser AM, Abd El Hakam FE, et al. Utility of Monocyte Expression of HLA-DR versus T Lymphocyte Frequency in the Assessment of COVID-19 Outcome. Int J Gen Med. 2022; 15: 5073-5087.

- Bonnet B, Cosme J, Dupuis C, Coupez E, Adda M, Calvet L, et al. Severe COVID-19 is characterized by the co-occurrence of moderate cytokine inflammation and severe monocyte dysregulation. EBioMedicine. 2021; 73: 103622.

- Serhan CN, Levy BD. Resolvins in inflammation: emergence of the pro-resolving superfamily of mediators. J Clin Invest. 2018; 128: 2657-2669.

- Philips RL, Wang Y, Cheon H, Kanno Y, Gadina M, Sartorelli V, et al. The JAK-STAT pathway at 30: Much learned, much more to do. Cell. 2022; 185: 3857-3876.

- Villarino AV, Kanno Y, Ferdinand JR, O’Shea JJ. Mechanisms of Jak/ STAT signaling in immunity and disease. J Immunol. 2015; 194: 21- 27.

- Starr R, Hilton DJ. Negative regulation of the JAK/STAT pathway. Bioessays. 1999; 21: 47-52.

- Valentino L, Pierre J. JAK/STAT signal transduction: regulators and implication in hematological malignancies. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006; 71: 713-721.

- Xia H, Cao Z, Xie X, Zhang X, Chen JY, Wang H, et al. Evasion of Type I Interferon by SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep. 2020; 33: 108234.

- Minkoff JM, tenOever B. Innate immune evasion strategies of SARS- CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023; 21: 178-194.

- Wen Y, Li C, Tang T, Luo C, Lu S, Lyu N, et al. SARS-CoV-2 ORF7a Protein Impedes Type I Interferon-Activated JAK/STAT Signaling by Interacting with HNRNPA2B1. Int J Mol Sci. 2025; 26: 5536.

- Kumar A, Ishida R, Strilets T, Cole J, Lopez-Orozco J, Fayad N, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Nonstructural Protein 1 Inhibits the Interferon Response by Causing Depletion of Key Host Signaling Factors. J Virol. 2021; 95: e0026621.

- Thakur N, Chakraborty P, Tufariello JM, Basler CF. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp14 binds Tollip and activates pro-inflammatory pathways while downregulating interferon-α and interferon-γ receptors. bioRxiv. 2024: 2024.12.12.628214.

- Patra T, Meyer K, Geerling L, Isbell TS, Hoft DF, Brien J, et al. SARS- CoV-2 spike protein promotes IL-6 trans-signaling by activation of angiotensin II receptor signaling in epithelial cells. PLoS Pathog. 2020; 16: e1009128.

- Cai Z, Ni W, Li W, Wu Z, Yao X, Zheng Y, et al. SARS-CoV-2 S protein disrupts the formation of ISGF3 complex through conserved S2 subunit to antagonize type I interferon response. J Virol. 2025; 99: e0151624.

- Mu J, Fang Y, Yang Q, Shu T, Wang A, Huang M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 N protein antagonizes type I interferon signaling by suppressing phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of STAT1 and STAT2. Cell Discov. 2020; 6: 65.

- Lu Y, Michel HA, Wang PH, Smith GL. Manipulation of innate immune signaling pathways by SARS-CoV-2 non-structural proteins. Front Microbiol. 2022; 13: 1027015.

- Zhang T, Ma C, Zhang Z, Zhang H, Hu H. NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. MedComm (2020). 2021; 2: 618-653.

- Guo Q, Jin Y, Chen X, Ye X, Shen X, Lin M, et al. NF-κB in biology and targeted therapy: new insights and translational implications. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024; 9: 53.

- Stephenson AA, Taggart DJ, Xu G, Fowler JD, Wu H, Suo Z. The inhibitor of κB kinase β (IKKβ) phosphorylates IκBα twice in a single binding event through a sequential mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2023; 299: 102796.

- Khan S, Shafiei MS, Longoria C, Schoggins JW, Savani RC, Zaki H. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein induces inflammation via TLR2-dependent activation of the NF-κB pathway. Elife. 2021; 10: e68563.

- Saeng-Chuto K, Madapong A, Kaeoket K, Piñeyro PE, Tantituvanont A, Nilubol D. Co-infection of porcine deltacoronavirus and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus induces early TRAF6-mediated NF-κB and IRF7 signaling pathways through TLRs. Sci Rep. 2022; 12: 19443.

- Zhou S, Lv P, Li M, Chen Z, Xin H, Reilly S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 E protein: Pathogenesis and potential therapeutic development. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023; 159: 114242.

- Nieto-Torres JL, Verdiá-Báguena C, Jimenez-Guardeño JM, Regla- Nava JA, Castaño-Rodriguez C, Fernandez-Delgado R, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus E protein transports calcium ions and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Virology. 2015; 485: 330-339.

- Guo X, Yang S, Cai Z, Zhu S, Wang H, Liu Q, et al. SARS-CoV-2 specific adaptations in N protein inhibit NF-κB activation and alter pathogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2025; 224: e202404131.

- Nie Y, Mou L, Long Q, Deng D, Hu R, Cheng J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a positively regulates NF-κB activity by enhancing IKKβ-NEMO interaction. Virus Res. 2023; 328: 199086.

- Hameedi MA, T Prates E, Garvin MR, Mathews II, Amos BK, Demerdash O, et al. Structural and functional characterization of NEMO cleavage by SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. Nat Commun. 2022; 13: 5285.

- Osipiuk J, Azizi SA, Dvorkin S, Endres M, Jedrzejczak R, Jones KA, et al. Structure of papain-like protease from SARS-CoV-2 and its complexes with non-covalent inhibitors. Nat Commun. 2021; 12: 743.

- Mahmoudvand S, Shokri S. Interactions between SARS coronavirus 2 papain-like protease and immune system: A potential drug target for the treatment of COVID-19. Scand J Immunol. 2021; 94: e13044.

- Zheng WH, Ni RZ, Ran XH, Mu D. Papain-like protease of SARS-CoV-2 inhibits dsRNA-induced type I interferon response partly by cleaving TBK1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2025; 777: 152244.

- Bahar ME, Kim HJ, Kim DR. Targeting the RAS/RAF/MAPK pathway

for cancer therapy: from mechanism to clinical studies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023; 8: 455.

- Tournier C, Dong C, Turner TK, Jones SN, Flavell RA, Davis RJ. MKK7 is an essential component of the JNK signal transduction pathway activated by proinflammatory cytokines. Genes Dev. 2001; 15: 1419-

- Yan H, He L, Lv D. The Role of the Dysregulated JNK Signaling Pathway in the Pathogenesis of Human Diseases and Its Potential Therapeutic Strategies: A Comprehensive Review. Biomolecules. 2024; 14: 243.

- Canovas B, Nebreda AR. Diversity and versatility of p38 kinase signalling in health and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021; 22: 346- 366.

- Morgan D, Berggren KL, Spiess CD, Smith HM, Tejwani A, Weir SJ, et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinase-2 (MK2) and its role in cell survival, inflammatory signaling, and migration in promoting cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2022; 61: 173-199.

- Engler M, Albers D, Von Maltitz P, Groß R, Münch J, Cirstea IC. ACE2- EGFR-MAPK signaling contributes to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Life Sci Alliance. 2023; 6: e202201880.

- Han Y, Kim S, Park T, Hwang H, Park S, Kim J, et al. Reduction of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variant infection by blocking the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway. Microbiol Spectr. 2024; 12: e0158324.

- Zheng M, Karki R, Williams EP, Yang D, Fitzpatrick E, Vogel P, et al. TLR2 senses the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein to produce inflammatory cytokines. Nat Immunol. 2021; 22: 829-838.

- arahani M, Niknam Z, Mohammadi Amirabad L, Amiri-Dashatan N, Koushki M, Nemati M, et al. Molecular pathways involved in COVID-19 and potential pathway-based therapeutic targets. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022; 145: 112420.

- Hemmat N, Asadzadeh Z, Ahangar NK, Alemohammad H, Najafzadeh B, Derakhshani A, et al. The roles of signaling pathways in SARS- CoV-2 infection; lessons learned from SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. Arch Virol. 2021;166: 675-696.

- Hassan SS, Choudhury PP, Dayhoff GW 2nd, Aljabali AAA, Uhal BD, Lundstrom K, et al. The importance of accessory protein variants in the pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2022; 717: 109124.

- Li W, Wang Y, Peng Q, Shi Y, Wan P, Yao Y, et al. SARS-CoV-2 NSP14 induces AP-1 transcriptional activity via its interaction with MEK. Mol Immunol. 2024; 175: 1-9.

- Zhang J, Ejikemeuwa A, Gerzanich V, Nasr M, Tang Q, Simard JM, et al. Understanding the Role of SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a in Viral Pathogenesis and COVID-19. Front Microbiol. 2022; 13: 854567.

- Hurtado-Tamayo J, Requena-Platek R, Enjuanes L, Bello-Perez M, SolaI. Contribution to pathogenesis of accessory proteins of deadly human coronaviruses. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023; 13: 1166839.

- Swanson KV, Deng M, Ting P Y. The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat Rev. Immunology. 2019.

- Xu H, Akinyemi IA, Chitre SA, Loeb JC, Lednicky JA, McIntosh MT, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viroporin encoded by ORF3a triggers the NLRP3 inflammatory pathway. Virology. 2022; 568: 13-22.Shi CS, Nabar NR, Huang NN, Kehrl JH. SARS-Coronavirus Open Reading Frame-8b triggers intracellular stress pathways and activates NLRP3 inflammasomes. Cell Death Discov. 2019; 5: 101.

- Reis G, Moreira Silva EAS, Medeiros Silva DC, Thabane L, Campos VHS, Ferreira TS, et al. Early Treatment with Pegylated Interferon Lambda for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2023; 388: 518-528.

- World Health Organization. Therapeutics and COVID-19: Living guideline, August 2025. World Health Organization, 2025.

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group; Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, Linsell L, et al. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384: 693-704.

- WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group; Shankar-Hari M, Vale CL, Godolphin PJ, Fisher D, Higgins JPT, Spiga F, et al. Association Between Administration of IL-6 Antagonists and Mortality Among Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19: A Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2021; 326: 499-518.

- Kyriazopoulou E, Poulakou G, Milionis H, Metallidis S, Adamis G, Tsiakos K, et al. Early treatment of COVID-19 with anakinra guided by soluble urokinase plasminogen receptor plasma levels: a double- blind, randomized controlled phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 2021; 27: 1752-1760.

-

Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, Tomashek KM, Wolfe CR, GhazaryanV, et al. Baricitinib plus Remdesivir for Hospitalized Adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384: 795-807.

- Malgie J, Schoones JW, Zeegers MP, Pijls BG. Decreased mortality and increased side effects in COVID-19 patients treated with IL-6 receptor antagonists: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021; 11: 21522.

- Minigulov N, Boranbayev K, Bekbossynova A, Gadilgereyeva B, Filchakova O. Structural proteins of human coronaviruses: what makes them different? Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024; 14: 1458383.

- Paranga TG, Mitu I, Pavel-Tanasa M, Rosu MF, Miftode IL, Constantinescu D, et al. Cytokine Storm in COVID-19: Exploring IL-6 Signaling and Cytokine-Microbiome Interactions as Emerging Therapeutic Approaches. Int J Mol Sci. 2024; 25: 11411.

- Korobova ZR, Arsentieva NA, Lyubimova NE, Totolian AA. Redefining Normal: Cytokine Dysregulation in Long COVID and the Post- Pandemic Healthy Donors. Int J Mol Sci. 2025; 26: 8432.