Application and Challenge of Metalloporphyrin Sensitizers in Noninvasive Dynamic Tumor Therapy

- 1. Pharmacy School, Guangdong Medical University, China

- 2. The Second affiliated hospital, Guangdong Medical University, China

- 3. Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology (SIAT), Chinese Academy of Sciences, China

ABSTRACT

Tumor treatment still face significant challenges. Though varies of treatment methods in clinic show certain therapeutic effects, serious side effects are often accompanied. Dynamic therapies, such as photodynamic therapy (PDT) and sonodynamic therapy (SDT), provide new opportunities for noninvasive tumor treatment. Sensitizers are crucial for dynamic therapy. Porphyrins and metalloporphyrins attract great attention due to their excellent photophysical properties and low cytotoxicity in dark. Metalloporphyrins shows greater potential for dynamic therapy because of the enhanced their photochemical and photophysical properties after metal ions coordinating to porphyrin rings. In this review, we introduced a comprehension on the mechanism of PDT and SDT, along with the recent progress in metalloporphyrins-based sensitizers against solid tumors. Additionally, the probable challenges and bottlenecks in clinical translation are also discussed.

KEYWORDS

- Metalloporphyrin

- Sensitizers

- Photodynamic therapy

- Sonodynamic therapy

- Antitumor

CITATION

Ouyang J, Li D, Zhu L, Liu L, Pan H, et al. (2024) Application and Challenge of Metalloporphyrin Sensitizers in Noninvasive Dynamic Tumor Therapy. J Materials Applied Sci 5(1): 1008.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is one of the leading causes of death worldwide, and its treatment continues to face significant challenges [1-4]. The popular treatment methods include surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy. Although each method shows certain therapeutic effects, serious side effects are often accompanied [5-8]. For instance, chemotherapy aims to quickly kill cancer cells using chemicals, but it also inevitably damages normal cells, leading to obvious side effects. Immunotherapy has been demonstrated significant clinical efficacy against malignant tumors in the blood system by activating the anti-tumor immune response; however, its therapeutic effect on solid tumors remains limitation [9]. Additionally, the introduction of too many cytotoxic T cells into the body during immunotherapy might trigger a severe cytokine storm, resulting in fever, low blood pressure, organ toxicity, and other side-effects [10]. Therefore, improving the therapeutic effect on tumors while minimizing side effects remains a significant challenge.

Noninvasive dynamic therapies, such as photodynamic therapy (PDT) and sonodynamic therapy (SDT), provide new opportunities for tumor treatment, especially for solid tumors [11-14]. After absorbing sensitizers, the tumor can be inhibited by light with specific wavelengths or ultrasound waves, which excite the sensitizers to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS, such as ·OH, 1O2, and -O2) to kill the tumor cells [15,16]. Because the sensitizers are of low- or non-toxicity in the absence of light and ultrasound irradiation, noninvasive dynamic therapies exhibit excellent antitumor potential. But light penetration is not strong enough to reach deep tumor lesions, therefore, PDT always shows efficiency for superficial tumors [17]. SDT is derived from PDT and aims to address the issue of poor light penetration [18,19]. Due to the deep penetration properties of ultrasound in soft tissue, SDT shows superior application prospects compared to PDT.

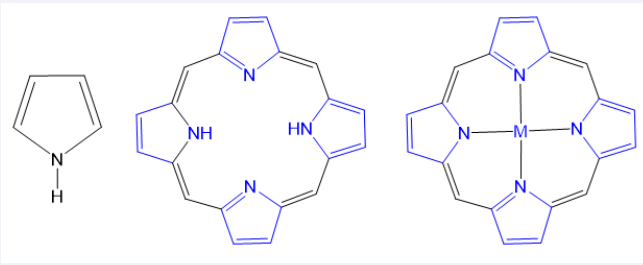

Sensitizers are a key to PDT/SDT. Porphyrins and their derivatives (such as hemoporphyrin, protoporphyrin, and ATX- 70) were first used in PDT and later in sonodynamic therapy SDT [20-22]. Porphyrins are a unique class of organic molecules with heterocyclic tetrapyrrole structures, and commonly found in nature. Structurally, porphyrin rings consist of four pyrrole units connected in a coplanar manner by four methylene bridges, forming a planar macrocyclic structure [Figure 1]. The internal cavity of porphyrins can coordinate metal ions to form metalloporphyrins. Porphyrins and metalloporphyrins have a highly conjugated π-bond system, which contributes to their efficient absorption of visible light, making them promising photosensitizers [23,24]. Moreover, compared to that of free porphyrins, the electrocatalytic and photophysical properties of metalloporphyrins can be significantly adjusted and even enhanced [25]. Studies have shown that metalloporphyrins have significant advantages, including high singlet oxygen yield, easy excitation, and a broad range of reactions [26]. To date, various metalloporphyrins have been utilized in biomedical applications and therapeutics [27-30]. In this review, we provided a comprehension on the mechanism of PDT and SDT, along with recent research on the metalloporphyrins as sensitizers in these therapies. Finally, the future prospects and challenges of using metalloporphyrins as sensitizers also discussed, offering theoretical insights for their application in sensitizers and other medical fields.

Figure 1 Typical structures, i.e., (A) pyrrole unit; (B) Porphyrin consist of four pyrrole rings joined by methane bridges, and (C) metalloporphyrin (M = Mn, Fe, Cu, Zn and so on).

The possible therapeutic mechanism of PDT and SDT

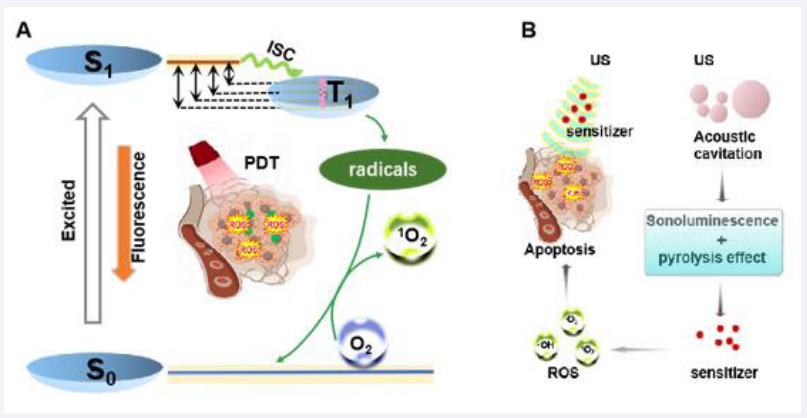

Sufficient ROS is the basis of PDT and SDT. In general view, ROS generation results from energy (triggered by light or ultrasound) transfer to sensitizers and electron transition [31,32]. These ROS increase oxidative stress levels in tumor cells, causing genetic and cell membrane damage, thus leading to apoptosis of cancer cells. However, the mechanism of ROS generation is not exactly the same, due to the different energy sources of PDT and SDT.

In PDT, after the sensitizer absorbs photon energy, electrons transition from S0 to S1. Following internal conversion, the excited electrons can return to the ground state through fluorescence emission. Alternatively, they can transition to a longer-lived triplet excited state (T1) via a non-radiative spin electr on transition [33]. During this process, excited state sensitizers react with surrounding reducing substances to form free radicals (·OH) or superoxide ions (-O2) and other ROS species through intersystem crossing (ISC). When the photosensitizers return from the excited T1 state to the ground state, the released energy is transferred to surrounding O2, converting it to singlet oxygen (1O2) [Figure 2A] [34].

Unlike the wave-particle duality of light, ultrasound is a mechanical wave. The unique effects caused by ultrasound (including cavitation and acoustic luminescence), cannot be ignored. In fact, there is no clear definition for the process of ROS production in SDT. One proposed mechanism is similar to PDT: the sonosensitizers transition to an excited state and induce ROS production, during the process that they return to the ground state. Conversely, the cavitation effect is widely accepted as the primary mechanism for ROS generation under ultrasound excitation [35]. When ultrasonic waves pass through an environment or tissue containing liquid, they cause microbubbles to oscillate in the sound field [36]. As the sound pressure increases, the microbubbles eventually implode, releasing much light (sonoluminescence) and heat [Figure 2B][37]. Sonoluminescence can stimulate the photochemical reaction of sonosensitizers, causing them to enter an excited state (S1), where they react with dissolved oxygen molecules or other substrate molecules to produce free radicals and superoxide ions. Meanwhile, as they return from the high-energy state to the ground state, the energy released by sonosensitizers is transferred to oxygen molecules, producing 1O2. Another perspective suggests that once the cavitation bubbles burst, the released heat produces local temperatures high enough to decompose the sonosensitizers, breaking some chemical bonds. This process causes the pyrolysis of water molecules, resulting in the production of hydroxyl radicals, or reactions with other endogenous substrates to produce additional free radicals [38]. Currently, the mechanism of ROS generation in SDT remains unclear and has not been accurately defined because of the complexity of sonodynamic processes. Significant efforts are needed to elucidate the underlying mechanism.

Figure 2 The possible mechanism of the PDT (A) and SDT (B).

Application of metalloporphyrins in PDT

Since hematoporphyrin was used as the first photosensitizer, porphyrins and their derivatives have attracted great interest in pharmaceutical science[27,39]. These compounds are considered excellent photosensitizers due to their exceptional light stability and biocompatibility. Metalloporphyrins are porphyrin derivatives with metal atoms inserted into the center of the porphyrin macrocycle. The combination of a metal with porphyrin can result in excellent physiological activity due to the additional unique physical and chemical properties of the metal elements. Some metalloporphyrins have been used as photosensitizers for PDT antitumor therapy [40-42]. For instance, Kevin et al., explored the effects of chelating copper or zinc into porphyrin liposomes (Cu-PoP and Zn-PoP) [43]. Cu-PoP and Zn-PoP exhibited unique photophysical properties with high fluorescence and ROS generation capabilities, indicating a strong antitumor effect. Moreover, compared to metal-free porphyrin liposomes, both Cu-PoP and Zn-PoP liposomes demonstrated reduced dark-toxicity in mice. Meanwhile, the liposomes provided targeted delivery, and drugs could be released upon light irradiation at the tumor site. Therefore, Cu-PoP and Zn-PoP enhanced therapeutic effects with good stability and reduced side effects. Wu et al. prepared a series of metalloporphyrin- indomethacin conjugates (PtPor, PdPor, and ZnPor) tethered with poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) chains [44]. Because of the heavy atom effect, the metal porphyrin complexes exhibited the higher 1O2 quantum yield than that of free base porphyrin (Por). The order of 1O2 yield of the synthesized metalloporphyrins was PtPor>PdPor>ZnPor, and all these complexes showed better 1O2 generation than Por.

Hypoxia is an important feature of tumor, and the oxygen consumption of PDT further aggravates hypoxia, thus affecting the therapeutic effect. Therefore, increasing the oxygen concentration in tumor or promoting the production of ROS in hypoxic condition is a strategy to improve PDT efficacy. Chen et al. designed a novel TiO-porphyrin nanosystem (FA-TiOPs) by encapsulating TiO-porphyrin (TiOP) in folate-liposomes for efficient PDT antitumor therapy under non-oxygen requirement [Figure 3A][45].

After the TiO- group was inserted into the center of the porphyrin to obtain TiOP, folate modified liposomes was used to load TiOP to form nanoparticles, which significantly improved the tumor targeting delivery of metalloporphyrins. From the results, TiOP had excellent photocatalytic properties, and photocatalyzed H2O to split into OH radical, H2O2, and O2 [Figure 3B]. Generated O2 not only conquered the hypoxia of tumor environment, but also was further excited by TiOP to generate 1O2 for killing tumor cells [Figure 3C]. Theoretical calculations indicated that the high energy in the excited state (S1) of TiOP and the narrow energy gap between S1 and the triplet excited state (Tn) might contribute to the efficient photocatalytic action. Due to the narrow energy gap of the lowest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), TiOP is easily excited to S1, and transitions to a longer-lived triplet excited state (Tn), during which, TiOP react with surrounding reducing substances to form ROS through ISC. When TiOP in the triplet excited state returns to the ground state, surrounding molecules such as water or oxygen effectively intercept the energy and produce ROS. Additionally, TiOP also catalyzed H2O2 to generate 1O2 under light excitation [Figures 3D and 3E]. This property induced much more ROS generation, as there is overexpressed H2O2 in tumors. Burst- released ROS indicated a specific anticancer effect [Figures 3F- 3H] with no harm to healthy mice [Figure 3I].

Figure 3 TiO−porphyrin-loaded liposome nanosystem (FA−TiOPs) to photocatalytize H2O and H2O2 for PDT antitumor therapy [45].

Metalloporphyrins often exhibit special functions from the properties of metal ions [46]. Mn(III) can induce protein oxidation of tumor cells. MnP coordinated by Mn(III) with ortho- N-alkyl- and N-alkoxyalkyl-porphyrins (MnPs) were developed as superoxide dismutases to assistantly induce protein oxidation and increase ROS levels for cancer treatment [47]. Pt(IV) is highly toxic to cancer cells by blocking the replication and transcription of DNA, ultimately leading to cell death, synergistically enhancing the PDT effect [48]. Schneider et al. reported a tetraplatinated (metallo)porphyrin-based photosensitizer, which showed effective phototoxicity under light irradiation and chemical destruction on multicellular tumor spheres [49].

In addition, metalloporphyrins, such as Mn- and Ga- porphyrins, have been used as magnetic resonance (MR) contrast agents [50,51]. Fazaeli et al. designed a Ga-porphyrin complex [52]. This radio-labeled porphyrin had strong PET imaging capability, integrating diagnosis and treatment using labeled metalloporphyrins. Similarly, Hu et al. synthesized a water- soluble and tumor-targeted metalloporphyrin photosensitizer (Ga-4cisPtTPyP) containing Ga(III) and Pt(II) ions [53]. This photosensitizer showed a high singlet oxygen yield (Φ?) and significant photocytotoxicity. Guided by MR imaging, Ga- 4cisPtTPyP almost completely inhibited tumor growth over two weeks in an in vivo PDT assay. Moreover, guided by multimodal imaging, the precise of therapy will be increased. Chen et al. prepared metalloporphyrin (Gd-TCPP)-based nanotheranostics (Gd-PNPs), realizing the efficient PDT under dual-model guidance of fluorescence (FL) and MR imaging [Figure 4][54]. Notably, the multifunctional Gd–TCPP served triple functions in Gd–PNPs as a FL imaging probe, MR contrast agent, and PS for PDT. Cellular PDT experiments confirmed that Gd–PNPs exhibited good tumor cell ablation efficacy under light irradiation. The in vivo study proved that Gd–PNPs showed excellent PDT effect in CT26 tumor- bearing mice guided by FL/MR imaging.

In addition to metalloporphyrin molecules, which were obtained by inserting metal ions into the center of the porphyrin rings, porphyrins and metalloporphyrins can also be used as organic linkers to assemble metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [55,56]. Due to the high diffusion rates of oxygen and ROS within the porous material, MOFs allow for highly efficient PDT. For instance, Liu et al. reported to assemble doxorubicin (DOX)-encapsulated zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIF- 8) on the surface of Zr(IV)-based porphyrinic MOFs[57]. The metalloporphyrinic MOFs harvested photons to produce plentiful ROS, thus leading to amplified chemo/PDT therapeutic efficacy. Similar phenomena were observed in other porphyrinic MOFs [58,59].

From the above research, it is clear that the insertion of different metal elements into the porphyrin center can not only alter its optical properties and enhance the antitumor effect but also reduce skin toxicity and improve biocompatibility [60]. Furthermore, by selecting metal ions with specific functions (such as imaging or chemotherapy) to chelate porphyrin rings, the antitumor effect can be significantly improved through combined diagnosis or multi-modal therapy [30]. Besides, metalloporphyrin-based MOF showed potential application of PDT due to the porous property and biocompatibility and biodegradability [56]. Despite the potential benefits of metalloporphyrins in PDT, the limited penetration depth of visible light has restricted the widespread application especially in deep-seated tumors, such as liver cancer, kidney cancer, and glioma [61-63]. It is a big challenge how to improve the PDT effect through structural modification of metalloporphyrins or optical technology.

Application of metalloporphyrins in SDT

SDT is developed on the basis of PDT, aiming to address the inherent defect of light and improve the therpay effect of deep lesion. Similar to PDT, SDT mainly generates ROS to kill tumor cells. Due to the deep penetration of US wave, it will create a broader application prospect for the dynamic therapy [64-66]. Since hematoporphyrin, which is the first commercially available photosensitizer, was found to significantly kill various cancer cells after ultrasound irradiation, it paved a way for the application of porphyrins and their derivatives in SDT.

Due to the special advantages of metal ions (such as low phototoxicity, high stability and functional diversity), a variety of metalloporphyrins have also been developed as sonosensitizers [24,67]. ATX-70, a Ga-porphyrin complex, was found to produce significant antitumor effects with both plane waves and focused waves, while avoiding damage to surrounding tissues [68,69]. Giuntini et al., demonstrated that the ultrasound activity of metalloporphyrins largely depends on the presence of metal ions [70]. Therefore, metalloporphyrins with different metal centers exhibit a variety of properties under ultrasound irradiation. Ma et al. synthesized three metalloporphyrins (MnTTP, ZnTTP, and TiOTTP) with different metal coordination as sonosensitizers to investigate the influence of metal centers on SDT [71]. These metalloporphyrins were respectively encapsulated with human serum albumin (HSA) to form nanoparticles (NPs), enhancing their biocompatibility and tumor-targeting ability. The results showed that these metalloporphyrins all could produce ROS under ultrasound irradiation [Figures 4A-4B]. Moreover, they could be remotely activated to generate ROS over a distance of

10 cm, demonstrating the excellent deep penetration ability of ultrasound [Figures 4C-4D]. This deep penetration ability was further demonstrated in mice [Figure 4E]. Additionally, the study proved that different metal centers greatly influence the ultrasound response of the metalloporphyrins. Among the three, MnTTP had the best ROS generation effect under ultrasound, which might be explained by the lowest gap energy between HOMO and LUMO, making it more easily excited by energy [Figure 4F]. Moreover, MnTTP-HSA is a successful example of photoacoustic/ magnetic resonance (PA/MR) imaging. Guided by dual-modal imaging, MnTTP-HSA realized the tumor precise inhibition. In another study, Ma et al. provided an urchin-shaped Cu-porphyrin (CuPP) liposome nanosystem (FA–L–CuPP) as a sonosensitizer [72]. FA–L–CuPP showed good tumor-targeting ability and ultrasound-mediated ROS generation. Molecular orbital distribution calculations indicated that strong intramolecular charge transfer of CuPP under US irradiation afforded energy to the surrounding O2 and H2O to generate ROS, which inhibited tumor growth as “ammunitions”. Similarly, Huang et al. anchored a mesoporous hollow structure with Mn-protoporphyrin IX onto its surface as a sonosensitizer, and demonstrated highly effective SDT antitumor activity and good MR imaging, achieving image- monitored tumor growth inhibition [73].

Figure 4 Gd–TCPP-based efficient PDT under dual-model guidance of FL and MR imaging [54].

Figure 5 The SDT effects of Metalloporphyrins with different metal centers.[71]

During the process of exploring the SDT mechanism of Mn-protoporphyrin IX (MnP), Chen et al. further discovered that ultrasound could not only activate MnP in tumors, but also triggered a systemic immune response to synergistically prevent tumor recurrence [74]. They designed a multifunctional nanosonosensitizer (FA-MnPs) by encapsulating MnP into folate- liposomes, a popular drug delivery carrier in cancer treatment to increase the accumulation of drugs in tumor [Figure 6]. Under US treatment, FA-MnPs exhibited excellent US-mediated deep response, and induced abundant 1O2 generation. Further exploration revealed the US irradiation mechanism of MnP, and the possible explaination for the enhanced US-ativating ability than the metal-free porphyrin (PP). FA-MnP showed excellent suppression to superficial and deep-seated tumors in mice, proving the effective in vivo SDT. Meanwhile, MnPs-mediated SDT also induced the re-polarization of macrophages from the immunosuppressive M2 type to the antitumor M1 type, and elicited ICD with the exposure and release of DAMPs, including high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and calreticulin (CRT). These DAMPs stimulated the maturation of dendritic cells (DCs), which subsequently activate the systemic immune response to synergistically suppress the tumors growth and recurrence.

Figure 6 Metalloporphyrin sonosensitizer mediated SDT-ICD antitumor.[74]

SDT effect not only depends on the ultrasound response ability of sonosensitizers, but is also directly connected to the concentration of oxygen at the tumor site. However, hypoxia is a unique characteristic of solid tumors due to the high consumption of oxygen by tumor cells and the insufficient supply from abnormal tumor vessels [75]. Therefore, increasing the oxygen supply is an efficient strategy to improve the SDT effect. Yin et al. developed an O2 -supplying nanosonosensitizer (FePO2 @HC) by encapsulating Fe-porphyrin (FeP) and O2 in human serum albumin (HSA) [76]. To enhance the penetration of the nanosonosensitizer into the tumor, collagenase (CLG) was fused into the nanoparticles to cut the tumor extracellular matrix like an artificial scissor [Figure 7A]. In FePO2 @HC, dioxygen was adducted to FeP. Theoretical calculations revealed that electrondonating FeP had a high affinity for dioxygen [Figure 7B]. Experimental results showed that FePO2 @HC rapidly released O2 in a deoxygenated PBS solution, suggesting the selective release of O2 in hypoxic environments [Figure 7C]. Meanwhile, the FePO2 @HC solution produced significant amounts of 1 O2 under US irradiation [Figure 7D]. In addition, due to the cutting function of CLG on the collagen fibers in the tumor [Figure 7E], FePO2 permeated into the tumor interior, and released O2 in the hypoxic environment, subsequently producing sufficient 1 O2 under US irradiation to inhibit tumor growth [Figure 7F]. In Zhu’s research on Fe-porphyrin, they found that Fe-porphyrin could kill tumor cells by Fenton reaction [77]. They prepared the Fe-porphyrin as a sonosensitizer (NTP) by assembling Fe3+ and meso-tetrakis (4-sulfonatophenyl) porphyrin (TPPS). The complex could not only be ultrasonically excited to generate ROS, but also undergo Fenton reactions with intracellular H2 O2 to produce ·OH. By combining SDT and the Fenton reaction, the Fe-porphyrin showed excellent antitumor effects. The multifunctionality of a single metalloporphyrin complex provided new design ideas for cancer therapy.

Figure 7 Oxygen-enhanced SDT based on Fe-porphyrin.[76]

Recently, several metalloporphyrin-based MOF sonosensitizers have shown good intrinsic SDT effects. Considering that Pt can convert overexpressed H2 O2 to O2 , and glucose oxidase (GOx) can reduce glucose, Bao et al. prepared a metalloporphyrinbased PCN-224 nanosonosensitizer through the self-assembly of Zr clusters and H2 TCPP [78]. Meanwhile, Pt NPs and GOx were encapsulated within the MOF. At the tumor site, Pt NPs were able to utilize endogenous H2 O2 to produce oxygen, alleviating tumor hypoxia and thus enhancing the SDT effect. The loaded GOx could consume glucose, achieving the tumor starvation therapy effect. The amplified synergistic therapy of SDT and starvation therapy efficiently inhibited tumor growth. Similarly, Niu et al. provided an effective strategy combining SDT and chemodynamic therapy (CDT) using a metalloporphyrin-integrated nanosystem (MOF@ MP-RGD), overcoming brain-related barriers to improve delivery [79]. xMOF-based sonosensitizers present a fundamental perspective in anticancer applications, aiming to highlight the improvements of SDT and synergistic therapies.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Metalloporphyrins have unique characteristics such as photocatalysis, electrocatalysis, and biomimetic catalysis. Moreover, they possess potential biological properties, such as biocompatibility, effective tumor retention, and various mimicking biological functions, making them extremely useful for biomedical applications, especially for PDT and SDT. Despite the growing number of impressive progress reports on metalloporphyrins, their biomedical applications in clinical settings are still in the early stages and face many challenges. First, in PDT, the depth of light penetration is limited, particularly for short visible wavelengths, making it difficult to effectively treat deep-seated tumors. Recently, new in vivo light source technologies (such as optical fibers and chemiluminescence) have emerged. Exploring how to use these technologies to enhance PDT effects is an attractive direction. Similarly, In SDT, there are still limitations in treating specific tumor sites, and new in vivo technologies are also required. Second, metalloporphyrins have excellent photophysical and photochemical properties, which provide advantages for their application in PDT and SDT. However, phototoxicity is a severe problem due to the continuous accumulation of these sensitizers in the skin during the repeated treatment. Reducing dark toxicity with ensuring dynamic effects is an important research content in a long term. Third, the stability and biocompatibility of metalloporphyrins in vivo directly affect their therapeutic efficacy and safety. Some metalloporphyrins may degrade or react with other molecules in the body, affecting their function. Ensuring their stability and compatibility is crucial for effective treatment. Finally, thorough and in-depth studies are necessary to understand the correlation between the fundamental parameters of metalloporphyrins and their biosafety, including biodistribution, pharmacokinetics, long- term toxicity, and clearance in vivo, to enable potential clinical translation. Overall, metalloporphyrins have great potential in tumor treatment. Moreover, benefited from the ROS generation of metalloporphyrins under light/ultrasound irradiation, the combination of PDT and SDT may synergistically increase the production of ROS in various ways, which would kill tumor cells with multiple mechanisms and improve therapy effec, and significant progress is expected in the biomedical field in the future.

AKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2021A1515010131); Guangdong Province Universities and Colleges Characteristic Innovation (2021KTSCX035); Project of Regional Joint Fund of Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (2023A1515140192); Construction Project of Nano Technology and Application Engineering Research Center of Guangdong Medical University (4SG24179G).

REFERENCES

- Ilic M, Ilic I. Cancer mortality in Serbia, 1991-2015: an age-period- cohort and joinpoint regression analysis. Cancer commun (Lond). 2018; 38: 10.

- Rollin G, Lages J, Shepelyansky DL. Wikipedia network analysis of cancer interactions and world influence. PloS one. 2019; 14: e0222508.

- Wu C, Li M, Meng H, Liu Y, Niu W, Zhou Y, et al. Analysis of status and countermeasures of cancer incidence and mortality in China. Sci China Life sci. 2019; 62: 640-647.

- Torre LA, Islami F, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A. Global Cancer in Women: Burden and Trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017; 26: 444-457.

- Schaue D, McBride WH. Opportunities and challenges of radiotherapy for treating cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015; 12: 527-540.

- Diesendruck Y, Benhar I. Novel immune check point inhibiting antibodies in cancer therapy—Opportunities and challenges. Drug Resist Updat. 2017; 30: 39-47.

- Phour A, Gaur V, Banerjee A, Bhattacharyya J. Recombinant protein polymers as carriers of chemotherapeutic agents. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2022; 190: 114544.

- Kong X, Gao P, Wang J, Fang Y, Hwang KC. Advances of medical nanorobots for future cancer treatments. J Hematol Oncol. 2023; 16: 74.

- Varadé J, Magadán S, González-Fernández Á. Human immunology and immunotherapy: main achievements and challenges. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021; 18: 805-828.

- Riley RS, June CH, Langer R, Mitchell MJ. Delivery technologies for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019; 18: 175-196.

- Chang M, Wang Z, Dong C, Zhou R, Chen L, Huang H, et al. Ultrasound- Amplified Enzyodynamic Tumor Therapy by Perovskite Nanoenzyme- Enabled Cell Pyroptosis and Cascade Catalysis. Adv Mater 2022; 35: e2208817.

- Chen S, Li B, Yue Y, Li Z, Qiao L, Qi G, et al. Smart Nanoassembly Enabling Activatable NIR Fluorescence and ROS Generation with Enhanced Tumor Penetration for Imaging-Guided Photodynamic Therapy. Adv Mater. 2024; 36: e2404296.

- Li X, Kwon N, Guo T, Liu Z, Yoon J. Innovative Strategies for Hypoxic- Tumor Photodynamic Therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018; 57: 11522-11531.

- Zhang Y, Zhang X, Yang H, Yu L, Xu Y, Sharma A. Advanced biotechnology-assisted precise sonodynamic therapy. Chem Soc Rev. 2021; 50: 11227-11248.

- Gong F, Cheng L, Yang N, Gong Y, Ni Y, Bai S,et al. Preparation of TiH(1.924) nanodots by liquid-phase exfoliation for enhanced sonodynamic cancer therapy. Nat commun. 2020; 11: 3712.

- Di Y, Deng R, Liu Z, Mao Y, Gao Y, Zhao Q, et al. Optimized strategies of ROS-based nanodynamic therapies for tumor theranostics. Biomaterials. 2023; 303: 122391.

- Zhou Z, Song J, Nie L, Chen X. Reactive oxygen species generating systems meeting challenges of photodynamic cancer therapy. Chem Soc Rev. 2016; 45: 6597-6626.

- Liang G, Sadhukhan T, Banerjee S, Tang D, Zhang H, Cui M, et al. Reduction of Platinum(IV) Prodrug Hemoglobin Nanoparticles with Deeply Penetrating Ultrasound Radiation for Tumor-Targeted Therapeutically Enhanced Anticancer Therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2023; 62: e202301074.

- Wu A, Jiang L, Xia C, Xu Q, Zhou B, Jin Z, et al. Ultrasound-Driven Piezoelectrocatalytic Immunoactivation of Deep Tumor. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2023; 10: e2303016.

- Guo S, Sun X, Cheng J, Xu H, Dan J, Shen J, et al. Apoptosis of THP-1 macrophages induced by protoporphyrin IX-mediated sonodynamic therapy. Int J Nanomedicine. 2013; 8: 2239-2246.

- Yumita N, Iwase Y, Nishi K, Komatsu H, Takeda K, Onodera K, et al. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in sonodynamically induced apoptosis using a novel porphyrin derivative. Theranostics. 2012; 2: 880-888.

- Umemura S, Yumita N, Nishigaki R. Enhancement of ultrasonically induced cell damage by a gallium-porphyrin complex, ATX-70. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1993; 84: 582-588.

- Hashimoto T, Choe YK, Nakano H, Hirao K. Theoretical Study of the Q and B Bands of Free-Base, Magnesium, and Zinc Porphyrins, and Their Derivatives. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 1999; 103: 1894-1904.

- Luo H, Yu W, Chen S, Wang Z, Tian Z, He J, et al. Application of metalloporphyrin sensitizers for the treatment or diagnosis of tumors. J Chem Res. 2022; 1-9.

- Liao M, Cui J, Yang M, Wei Z, Xie Y, Lu C. Photoinduced electron transfer in metalloporphyrins. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2022; 1267: 133591.

- Pereira MM, Dias LD, Calvete MJF. Metalloporphyrins: Bioinspired Oxidation Catalysts. ACS Catalysis. 2018; 8: 10784–10808.

- Ethirajan M, Chen Y, Joshi P, Pandey RK. The role of porphyrin chemistry in tumor imaging and photodynamic therapy. Chem Soc Rev. 2011; 40: 340-362.

- Faustova M, Nikolskaya E, Sokol M, Fomicheva M, Petrov R, Yabbarov N. Metalloporphyrins in Medicine: From History to Recent Trends. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2020; 3: 8146-8171.

- Jiang L, Chee PL, Gao J, Gan CRR, Owh C. Lakshminarayanan R, et al. A New Potent Antimicrobial Metalloporphyrin. Chem Asian J. 2021; 16: 1007-1015.

- Shao S, Rajendiran V, Lovell JF. Metalloporphyrin Nanoparticles: Coordinating Diverse Theranostic Functions. Coord Chem Rev. 2019; 379: 99-120.

- Maeda K, Domen K. Photocatalytic Water Splitting: Recent Progress and Future Challenges. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 2010; 1: 2655-2661.

- Hu F, Xu S, Liu B. Photosensitizers with Aggregation-Induced Emission: Materials and Biomedical Applications. Adv Mater. 2018; 30: e1801350.

- Pass HI. Photodynamic therapy in oncology: mechanisms and clinical use. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993; 85: 443-456.

- Klaper M, Fudickar W, Linker T. Role of Distance in Singlet Oxygen Applications: A Model System. J Am Chem Soc. 2016; 138: 7024-7029.

- Zhou Y, Wang M, Dai Z. The molecular design of and challenges relating to sensitizers for cancer sonodynamic therapy. Materials Chemistry Frontiers. 2020; 4: 2223-2234.

- Lafond M, Yoshizawa S, Umemura S-I. Sonodynamic Therapy: Advances and Challenges in Clinical Translation. J Ultrasound Med. 2019; 38: 567-580.

- Wu J, Nyborg WL. Ultrasound, cavitation bubbles and their interaction with cells. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008; 60: 1103-1116.

- Misík V, Riesz P, Free Radical Intermediates in Sonodynamic Therapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000; 899: 335-348.

- Chen H, Wang Y, Wang W, Cao T, Zhang L, Wang Z, et al. High- yield porphyrin production through metabolic engineering and biocatalysis. Nat Biotechnol. 2024.

- Abbas G, Alibrahim F, Kankouni R, Al-Belushi S, Al-Mutairi DA, Tovmasyan A, et al. Effect of the nature of the chelated metal on the photodynamic activity of metalloporphyrins. Free Radic. Res. 2023; 57: 487-499.

- Sehgal P, Narula AK. Metal substituted metalloporphyrins as efficient photosensitizers for enhanced solar energy conversion. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry. 2019; 375: 91-99.

- Stanojevi? A, Milovanovi? B, Stankovi? I, Etinski M, Petkovi? M. The significance of the metal cation in guanine-quartet – metalloporphyrin complexes. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2021; 23: 574-584.

- Carter KA, Wang S, Geng J, Luo D, Shao S, Lovell JF. Metal Chelation Modulates Phototherapeutic Properties of Mitoxantrone-Loaded Porphyrin-Phospholipid Liposomes. Mol Pharm. 2016; 13: 420-427.

- Wu F, Yang M, Zhang J, Zhu S, Shi M, Wang K. Metalloporphyrin- indomethacin conjugates as new photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2018; 24: 53-60.

- Chen H, Ma A, Yin T, Chen Z, Liang R, Pan H, et al. In Situ Photocatalysis of TiO–Porphyrin-Encapsulated Nanosystem for Highly Efficient Oxidative Damage against Hypoxic Tumors. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020; 12: 12573-12583.

- El-Mahalawy AM, Nawar AM, Wassel AR. Efficacy assessment of metalloporphyrins as functional materials for photodetection applications: role of central tetrapyrrole metal ions. Journal of Materials Science. 2022; 57: 15413–15439.

- Batinic-Haberle I, Tovmasyan A, Huang Z, Duan W, Du L, Siamakpour- Reihani S, et al. H(2)O(2)-Driven Anticancer Activity of Mn Porphyrins and the Underlying Molecular Pathways. Oxid med cell longev. 2021; 2021: 6653790.

- Liu B, Li C, Chen G, Liu B, Deng X, Wei Y, et al. Synthesis and Optimization of MoS2@Fe3O4-ICG/Pt(IV) Nanoflowers for MR/IR/ PA Bioimaging and Combined PTT/PDT/Chemotherapy Triggered by 808 nm Laser. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2017; 4: 1600540.

- Schneider L, Kalt M, Larocca M, Babu V, Spingler B. Potent PBS/ Polysorbate-Soluble Transplatin-Derived Porphyrin-Based Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. Inorg chem. 2021; 60: 9416-9426.

- Fu X, Cai Z, Fu S, Cai H, Li M, Gu H, et al. Porphyrin-Based Self- Assembled Nanoparticles for PET/MR Imaging of Sentinel Lymph Node Metastasis. ACS appl mater interfaces. 2024; 16: 27139-27150.

- Mouraviev V, Venkatraman TN, Tovmasyan A, Kimura M, Tsivian M, Mouravieva V, et al. Mn porphyrins as novel molecular magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. J Endourol 2012; 26: 1420-1424.

- Fazaeli Y, Jalilian AR, Amini MM, Ardaneh K, Rahiminejad A, Bolourinovin F, et al. Development of a (68)Ga-Fluorinated Porphyrin Complex as a Possible PET Imaging Agent. Nucl med mol imaging. 2012; 46: 20-26.

- Hu X, Ogawa K, Kiwada T, Odani A. Water-soluble metalloporphyrinates with excellent photo-induced anticancer activity resulting from high tumor accumulation. J Inorg Biochem. 2017; 170: 1-7.

- Chen W, Zhao J, Hou M, Yang M, Yi C. Gadolinium–porphyrin based polymer nanotheranostics for fluorescence/magnetic resonance imaging guided photodynamic therapy. Nanoscale. 2021; 13: 16197-16206.

- Gao P, Hussain MZ, Zhou Z, Warnan J, Elsner M, Fischer RA. Zr-based metalloporphyrin MOF probe for electrochemical detection of parathion-methyl. Biosens Bioelectron. 2024; 261: 116515.

- Leng F, Liu H, Ding M, Lin QP, Jiang HL. Boosting Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production of Porphyrinic MOFs: The Metal Location in Metalloporphyrin Matters. ACS Catalysis. 2018; 8: 4583-4590.

- Liu B, Liu Z, Lu X, Wu P, Sun Z, Chu H, et al. Controllable growth of drug-encapsulated metal-organic framework (MOF) on porphyrinic MOF for PDT/chemo-combined therapy. Materials & Design. 2023; 228: 111861.

- Liu J, Yang Y, Zhu W, Yi X, Dong Z, Xu X, et al. Nanoscale metal-organic frameworks for combined photodynamic & radiation therapy in cancer treatment. Biomaterials. 2016; 97: 1-9.

- Zhao Y, Kuang Y, Liu M, Wang J, Pei R. Synthesis of Metal–Organic Framework Nanosheets with High Relaxation Rate and Singlet Oxygen Yield. Chemistry of Materials. 2018; 30: 7511-7520.

- Horváth O, Valicsek Z, Fodor MA, Major MM, Imran, M, Grampp G, et al. Visible light-driven photophysics and photochemistry of water- soluble metalloporphyrins. Coord Chem Rev. 2016; 325: 59-66.

- Wei Z , Liang P, Xie J, Song C, Tang C, Wang Y, et al. Carrier-free nano- integrated strategy for synergetic cancer anti-angiogenic therapy and phototherapy. Chemical sci. 2019; 10: 2778-2784.

- Guan X, Yin HH, Xu XH, Xu G, Zhang Y, Zhou BG, et al. Tumor Metabolism-Engineered Composite Nanoplatforms Potentiate Sonodynamic Therapy via Reshaping Tumor Microenvironment and Facilitating Electron-Hole Pairs’ Separation. Adv Funct Mater. 2020; 30: 2000326.

- Lin X, Song J, Chen X, Yang H. Ultrasound-Activated Sensitizers and Applications. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2020; 59: 14212-14233.

- Liang S, Yao J, Liu D, Rao L, Chen X, Wang Z. Harnessing Nanomaterials for Cancer Sonodynamic Immunotherapy. Adv Mater. 2023; 35: e2211130.

- Chen J, Luo H, Liu Y, Zhang W, Li H, Luo T, et al. Oxygen-Self-Produced Nanoplatform for Relieving Hypoxia and Breaking Resistance to Sonodynamic Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer. ACS Nano. 2017; 11: 12849-12862.

- Tang J, Zhang X, Cheng L, Liu Y, Chen Y, Jiang Z, et al. Multiple stimuli-responsive nanosystem for potent, ROS-amplifying, chemo- sonodynamic antitumor therapy. Bioact Mater. 2021; 15: 355-371.

- Yuan M, Liang S, Zhou Y, Xiao X, Liu B, Yang C, et al. A Robust Oxygen- Carrying Hemoglobin-Based Natural Sonosensitizer for Sonodynamic Cancer Therapy. Nano Lett. 2021; 21: 6042-6050.

- Yumita N, Okudaira K, Momose Y, Umemura SI. Sonodynamically induced apoptosis and active oxygen generation by gallium- porphyrin complex, ATX-70. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2010; 66: 1071-1078.

- Yumita N, Sasaki K, Umemura S, Nishigaki R. Sonodynamically induced antitumor effect of a gallium-porphyrin complex, ATX-70. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1996; 87: 310-316.

- Giuntini F, Foglietta F, Marucco AM, Troia A, Dezhkunov NV, Pozzoli A, et al. Insight into ultrasound-mediated reactive oxygen species generation by various metal-porphyrin complexes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018; 121: 190-201.

- Ma A, Chen H, Cui Y, Luo Z, Liang R, Wu Z, et al. Metalloporphyrin Complex-Based Nanosonosensitizers for Deep-Tissue Tumor Theranostics by Noninvasive Sonodynamic Therapy. Small. 2019; 15: e1804028.

- Zhang L, Yin T, Zhang B, Yan C, Lu, C, Liu L, et al. Cancer-macrophage hybrid membrane-camouflaged photochlor for enhanced sonodynamic therapy against triple-negative breast cancer. Nano Research. 2022; 15: 4224-4232.

- Huang P, Qian X, Chen Y, Yu L, Lin H, Wang L, et al. Metalloporphyrin- Encapsulated Biodegradable Nanosystems for Highly Efficient Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Guided Sonodynamic Cancer Therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2017; 139: 1275-1284.

- Chen H, Liu L, Ma A, Yin T, Chen Z, Liang R, et al. Noninvasively immunogenic sonodynamic therapy with manganese protoporphyrin liposomes against triple-negative breast cancer. Biomaterials. 2021; 269: 120639.

- Petrova V, Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli M, Melino G, Amelio I. The hypoxic tumour microenvironment. Oncogenesis. 2018; 7: 10.

- Yin T, Chen H, Ma A, Pan H, Chen Z, Tang X, et al. Cleavable collagenase- assistant nanosonosensitizer for tumor penetration and sonodynamic therapy. Biomaterials. 2023; 293: 121992.

- Zhu J, Chu C, Li D, Pang X, Zheng H, Wang J, et al. Fe(III)-Porphyrin Sonotheranostics: A Green Triple-Regulated ROS Generation Nanoplatform for Enhanced Cancer Imaging and Therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2019; 29: 1904056.

- Bao Y, Chen J, Qiu H, Zhang C, Huang P, Mao Z. et al. Erythrocyte Membrane-Camouflaged PCN-224 Nanocarriers Integrated with Platinum Nanoparticles and Glucose Oxidase for Enhanced Tumor Sonodynamic Therapy and Synergistic Starvation Therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021; 13: 24532-24542.

- Niu H, Chen J, Jin J, Qi X, Bai K, Shu C, et al. Engineering metalloporphyrin-integrated nanosystems for targeted sono-/ chemo- dynamic therapy of leptomeningeal carcinomatosis through intrathecal administration. Chem Eng J. 2022; 437: 135373.

![TiO?porphyrin-loaded liposome nanosystem (FA?TiOPs) to photocatalytize H2O and H2O2 for PDT antitumor therapy [45].](https://www.jscimedcentral.com/public/assets/images/uploads/image-1737542365-1.png)

![Gd–TCPP-based efficient PDT under dual-model guidance of FL and MR imaging [54].](https://www.jscimedcentral.com/public/assets/images/uploads/image-1737542430-1.png)

![The SDT effects of Metalloporphyrins with different metal centers.[71]](https://www.jscimedcentral.com/public/assets/images/uploads/image-1737542450-1.png)

![Metalloporphyrin sonosensitizer mediated SDT-ICD antitumor.[74]](https://www.jscimedcentral.com/public/assets/images/uploads/image-1737543265-1.png)

![Oxygen-enhanced SDT based on Fe-porphyrin.[76]](https://www.jscimedcentral.com/public/assets/images/uploads/image-1737544655-1.png)