Maintaining Quality of Life for Residents with Dementia in Long-Term Care Settings

- 1. School of Aging Studies, University of South Florida, USA

Abstract

Cognitive impairment compromises quality of life. This review will indicate how it is possible to maintain quality of life in resident with dementia who lives in a long-term care setting by providing appropriate care. This care must address three main factors: meaningful activities, neuropsychiatric behavioral problems, and medical issues. Meaningful activities must be provided by caregivers because residents with dementia cannot initiate activities they enjoyed in the past. The activities must be tailored to the severity of dementia, should be provided 7 days/week, and available also for residents with advanced and terminal dementia (e.g., by involvement in the Namaste Care). Physical and environmental causes of behavioral problems should be identified and eliminated. It is important to consider circumstances in which behavioral problems occur and distinguish between agitation and rejection of care because they could be prevented by different interventions: agitation by involvement in meaningful activities, and rejection of care by improved communication and changes in care strategies. Depression increases risk of both symptoms and should be effectively treated. Treatment of medical problems should take into consideration goals of care determined by residents or their families, and that any medical intervention may cause discomfort. Therefore, interventions that do not meet goals of care and cause discomfort should be eliminated. There is no evidence that cardiopulmonary resuscitation and tube feeding are beneficial in advanced dementia. Mobility should be maintained for as long as possible because it improves ability to participate in meaningful activities and decreases the risk of medical problems, e.g. inter current infections and pressure ulcers.

Keywords

• Dementia

• Quality of life

• Activities

• Agitation

• Rejection of care

• Goals of care

Citation

Volicer L (2016) Maintaining Quality of Life for Residents with Dementia in Long-Term Care Settings. J Mem Disord Rehabil 1(1): 1001.

INTRODUCTION

Dementia is becoming a worldwide problem because residents live longer and age is the main risk factor for development of cognitive impairments. Worldwide, 47.5 million residents have dementia and there are 7.7 million new cases every year. Dementia is one of the major causes of disability and dependency among older resident’s worldwide. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia and may contribute to 60–70% of cases [1].

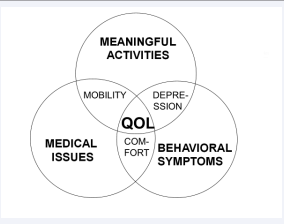

The main cause of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease and while many medications were tested for treatment or prevention of this disease, all of these tests were negative. The current medications do not prevent the disease progression but only slow it down and treat some of the symptoms. Therefore, we need to develop strategies for management of residents with dementia that have the potential to assure the best quality of life despite the disease progression. Quality of life is a very individual concept and is usually evaluated by an interview of the specific person. Unfortunately, dementia development leads to speech and comprehension problems making interview evaluation quality of life impossible. The concept, presented in this paper, postulates that quality of life for residents with dementia depends on three main factors: availability of meaningful activities, management of behavioral symptoms of dementia, and appropriate treatment of medical conditions (Figure 1) [2].

Figure 1: Factors needed to maintain quality of life (QOL) in persons with dementia (modified from “Enhancing the Quality of Life in Advanced Dementia”, L. Volicer and L. Bloom-Charette (eds.), Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis, 1999)

This model was developed based on clinical experience of a team of care providers on a dementia special care unit. The purpose of this review is to present the model, and the care issues which it raises, to providers of care in long-term care facilities, where many persons with advanced dementia receive care.

Meaningful activities

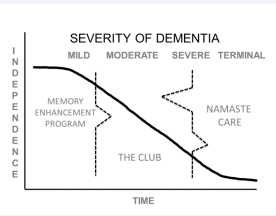

The activities provided in skilled nursing facilities, assisted living communities and day care program must be tailored to the severity of dementia and individual preferences. Considering stages of dementia, there is a need for three types of activities (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Activity programs for persons with dementia.

Persons with mild cognitive impairment and early stage dementia might not be comfortable to participate in activities meant for persons who are cognitive intact and isolate themselves in their rooms. They are often found sitting near the door of a dining room, because they forgot the meal times. The cognitively intact residents may criticize residents who ask the same question repeatedly. One program has been successful for helping residents with mild memory loss feeling comfortable in a social environment. These residents gather after breakfast in a small group with a staff member who guides throughout the day. Activities include reality orientation by reading a newspaper, easy trivia questions, reminiscence and a variety of brain exercises. This small group (10-15) meets daily and may attend appropriate programs with cognitively intact residents, e.g., physical exercises and entertainment [3]. Reports from nursing staff indicate that belonging and being accepted in a small group lowers the stress and slows cognitive decline (Joyce Simard, personal communication).

Residents with moderate dementia require different group activities. They rarely self-initiate an activity and need staff to keep them engaged. One program offers an opportunity to participate in a volunteer activity as soon as they finish their breakfast. It is useful to use individual Montessori type of activities [4], e.g., sorting of cards, buttons or coupons for the staff. They are thanked for their volunteer work which helps to improve their self-esteem. This group meets daily and becomes a family. One activity flows into another so the residents are engaged during all their waking hours. The day begins with a ritual, e.g., in the USA with the Pledge of Allegiance and singing God Bless America. All activities should be failure proof and include mental and physical exercises [5].

Persons with advanced dementia may not be able to participate even in simple activities. They are usually immobile and restricted to bed or chair, isolated in their rooms or placed in a hallway or on the periphery of an activity in which they cannot participate [6]. However, even these persons need to be involved in activities that improve their quality of life. One of the programs, designed specifically for persons who cannot benefit from usual activities is Namaste Care [7]. This program has two main components: a calm environment and loving touch approached to care [8]. The space where Namaste Care is offered is as free from distractions as possible, lights are lowered, calming music is playing and scent of lavender permeates the room. A small group of persons with advanced dementia are made comfortable in recliners, soft blanket tucked around them, and are continually offered beverages throughout the morning and afternoon sessions. They are always in presence of a care provider who interacts with them. Meaningful activities include activities of daily living offered with a loving touch approach. Faces, hands and arms are gently washed and moisturized by application of familiar scented cream. Seasonal and holiday items are shown, blowing bubbles brings smiles and laughter, which is an important part of Namaste Care. Namaste Care decreased agitation, improved appetite and communication and decreased pain complaints and rejection of care [8,9] Namaste Care improved quality of family visits and job satisfaction for the staff because they found the job more rewarding and less challenging because residents were not rejecting care.

Behavioral symptoms

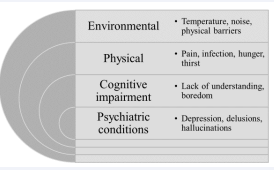

There are many causes of behavioral symptoms in persons with dementia. They include environmental and physical factors, cognitive impairment and psychiatric conditions (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Causes of behavioral symptoms of dementia

In residents with dementia, several neuropsychiatric symptoms can appear and increase as dementia progresses. These include psychiatric symptoms (delusions and hallucinations) as well as affective and behavioural symptoms (depressive mood, anxiety, irritability/liability, apathy, euphoria, disinhibition, aberrant motor activities, sleep disturbance and eating disorder). Survey of 200 physicians involved in long-term care showed that the most common behavioral symptoms in residents with dementia that required treatment were resisting care in 71% of cases with physical aggression toward staff in 56% of cases, vocal or verbal behaviors that disturbed others in 63% of cases, and restlessness in 50% of cases [10]. This indicates that there are two types of problem behaviors, 1. Resisting care with physical aggression when interacting with others and 2. Restlessness and vocal behavior disturbing others that occur when the resident is not interacting with others. This distinction is supported by an evaluation of behaviors in the Minimal Data Set 3.0 (MDS) that must be performed periodically on all nursing home residents. The MDS separates behavioral symptoms directed towards others and symptoms not directed towards others and uses rejection of care instead of resisting care [11].

Development of treatment strategies for behavioral symptoms of dementia is hindered by confusing terminology. Some investigators treat the symptoms as a black box, using terms like Behavioral and Psychiatric Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD) or Neuropsychiatric Symptoms (NPS). The first scale, developed for measuring behavioral symptoms of dementia, included all symptoms under the term “Agitation”[12]. The problem is, that treatments may be found to be ineffective if they affect only one type of the behaviors. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory [13], considered to be the gold standard for behaviour assessment in dementia, combines agitation and aggression in one its ten domains and has separate domain for Aberrant motor activities.However, questions in Agitation/aggression domain are really measuring rejection of care, which may lead to reactive aggression, while most agitation is measured by questions in the Aberrant motor activities domain, except for disruptive vocalization [14]. Although majority of experts polled by the International Psychiatric Association felt that aggression is part of agitation I believe that it is important to define and distinguish these two behavioral syndromesbecause the non-pharmacological strategies for management of these syndromes are different. Therefore, this review will be limited to two main behavioural problems and will separate agitation from rejection of care/aggression.

Agitation

can be defined as “behaviors that communicate to others [who observe the patient] that the patient is experiencing an unpleasant state of excitement and which remain after interventions to reduce internal or external stimuli have been carried out” [15]. It occurs when the persons with dementia is solitary and is not interacting with others. Symptoms of agitation include general restlessness, repetitive mannerisms, pacing, inappropriate dressing and undressing and repetitive vocalization. If all the possible environmental and physical causes of agitation are eliminated, the cause of agitation may be boredom. Therefore, involvement in meaningful activities may be the best treatment for agitation [16]

Rejection of care

occurs when a person with dementia does not understand intentions of a caregiver or the need for the care [17]. If the care provider insists on providing care, the person with dementia may defend himself/herself from being touched, may become combative and may even strike the care provider. Such a resident then may be called aggressive but such a label is blaming the victim because the resident with dementia considers the care provider to be the aggressor. Some residents with dementia do not tolerated being touch by others and develop this reactive aggression. The best strategies for management of rejection of care are improved communication and change in the care strategy. For instance, replacing a shower or tub bath with a bed bath decreases significantly rejection of care during bathing [18]. Rejection of care is also decreased when the residents are exposed to frequent comfortable touch by hand, scalp or feet massage.

Treatment of other behavioral problems requires specific non-pharmacological or pharmacological strategies and is beyond the scope of this review, with the exception depression treatment. Depression has an impact on both behavioral symptoms and engagement in meaningful activities and is discussed below.

Treatment of medical conditions.

Residents with dementia may suffer from chronic medical conditions and develop intercurrent illnesses. There are some conditions that are more common in persons with dementia than in general population, which include Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, sensory impairments, infections, malnutrition, hip fractures and other injuries, and pressure sores [19]. Treatment of these conditions should take into consideration lower life expectancy of persons with dementia, induction of discomfort caused by medical interventions, and inability of persons with advanced dementia to report symptoms of their diseases and adverse effects of medications. Therefore, treatments that have only long term effects (e.g., diets and medications lowering cholesterol levels) may not be indicated. Treatment should also try to prevent adverse effects of medications, e.g., hypoglycemic episodes in diabetics and overaggressive blood pressure control in hypertension. The two main medical problems in residents with advanced dementia are intercurrent infections and eating difficulties because they affect not only quality of life but also survival. Another condition, which may severely affect quality of life, is pain that will be discussed in the Comfort section.

Intercurrent infections

Infections occur quite frequently in residents with advanced dementia. They are almost an inevitable consequence of advance dementia because of several risk factors which develop with dementia progression. These risk factors include changes in function, difficulties in diagnosing infections, incontinence, decreased mobility, and aspiration. Changes in immune function include loss of thymic and t-lymphocyte function with age, skin anergy in 60% of impaired nursing home residents, and changes in cytokine secretion [20]. Infections are difficult to diagnose if the resident with dementia hasa decreased ability to report symptoms and their locations because of aphasia or memory deficits. Infections in elderly persons may also have altered clinical presentations and the absence of a fever. Incontinence predisposes residents with dementia to urinary infections, especially if indwelling or external catheters are used [21]. Decreased mobility also increases the risk of developing urinary tract infections [22] and pneumonia [23]. Aspiration will be discussed later with eating difficulties.

Treatment of intercurrent infections may sometime result in transfer to an acute care setting. However, there is good evidence that it is better to treat an infection in a long-term care setting without transfer. Short term mortality may be similar in residents with dementia treated in the long-term setting and in a hospital, but residents treated in a hospital have significant decrease of their functional status [24]. Therefore, residents who developed pneumonia should be treated in long-term care facility, unless they have a high respiratory rate and significant co morbidities.

Use of antibiotics for treatment of intercurrent infection in residents with dementia often has many adverse effects not only for the resident receiving the antibiotic, but also for the nursing home community, and the whole society. Individual adverse effects include gastrointestinal symptoms, allergic reactions and idiosyncratic reactions including agranulocytosis [25]. Gastrointestinal symptoms include diarrhea, nausea and flatulence. These symptoms are caused by alteration of the physiological gut micro flora leading to reduced microbial metabolism of carbohydrates and bile acid. The diarrhea is mainly osmotic but may be aggravated by facultative enteropathogens [26]. The most dangerous of them is Clostridium difficile which may cause life-threatening pseudo membranous colitis. Recently, a hyper virulent strain of C. diff. developed that may cause sepsis and toxic mega colon and to which nursing home residents are particularly vulnerable [27]. Prevalence of allergic reactions caused by antibiotics increases with aging [28] and may include anaphylactic reaction [29].

Frequent use of antibiotics in a nursing home may result in an epidemic of C. diff. infection and development of highly resistant pathogens. These pathogens include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, and multiple-drug-resistant gram-negative bacilli [30]. Overuse of antibiotics in a long-term care facility is promoted by diagnostic uncertainty, failure to recognize fever’s clinical manifestation in the elderly, treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria and bacterial colonization [31]. Therefore, it is important to carefully balance burdens and benefits of an antibiotic treatment. In advanced dementia, use of antibiotics for treatment of pneumonia does not increase comfort [32] may just prolong the dying process instead of improving long-term survival [33].

There is also evidence that hydration status may be more important for treatment of infections than antibiotics. Residents who had sufficient fluid intake, defined as more than 1500 mL daily [previous 7 days] or evidence that fluid loss did not exceed fluid intake [previous 3 days] had exactly the same morality rate after developing nursing home–acquired lower respiratory infection whether they received antibiotics or not [34]. Insufficient hydration increased mortality in both residents treated and not treated with antibiotics but this increase was much larger in residents not receiving antibiotics. Therefore, maintaining hydration status may be the most important strategy in residents with dementia who are at higher risk for development of infections. However, dehydration during dying is not uncomfortable [35] except for dryness of the mouth can be easily managed. Dehydration may actually increase comfort because decreased secretions minimize diarrhea, vomiting and need for suctioning [36] and there may be decreased perception of pain [37].

Eating difficulties

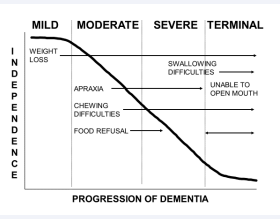

Maintaining adequate nutrition and hydration may be challenging for residents with dementia who develop eating difficulties. These may develop early in the course of dementia. Weight loss actually occurs in women before dementia diagnosis [38]. This weight loss could be related to pre dementia apathy, loss of initiative, and reduced olfactory function. As dementia progresses, eating difficulties may include apraxia, chewing difficulties and food refusal (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Eating difficulties in persons with dementia.

Apraxia may make residents with dementia unable to use utensils, but they may still feed themselves if they are provided finger food. Chewing difficulties can be managed by changing textures of the food.

Food refusal could be caused by several physical and environmental factors: fatigue, over stimulation, not feeling good, constipation/impaction, intercurrent illnesses, nausea, dehydration, oral problems with gingivae, teeth or ill-fitting dentures, and xerostomia [39]. Residents with dementia may reject institutional food, which may be sometimes unfamiliar to them. However, food refusal could be a symptom of depression, which requires careful evaluation and treatment if necessary but could be also a voluntary decision of the person with dementia that he/she do not want to live any longer with advanced dementia.

In the later stages of dementia, residents are unable to feed themselves, develop swallowing difficulties and eventually orofacial dyspraxia that makes them unable to open their mouths. Swallowing difficulties could lead to coughing during feeding and drinking, and increase the risk of aspiration. However, coughing by itself is not a sign of aspiration because coughing reflex prevents aspiration and aspiration risk can be reduced by medications that potentiate coughing reflex, e.g., anti-Parkinson medications [40], and angiotensin-converting-enzyme antagonists [41]. Aspiration of saliva is more dangerous than aspiration of food and liquids because the high number of pathogens in saliva. Risk of aspiration can be decreased by meticulous oral care and by oral rinse with 0.12% of chlorhexidine gluconate that decreases number of pathogens in saliva [42]. Not every resident who aspirates food and liquids develop aspiration pneumonia. A study, that followed documented aspirators for 4 years found that only 38% of them developed pneumonia [43].

With all medical conditions, it should be recognized that advanced dementia is a terminal disease. Therefore, the main goal of care may be maintenance of comfort instead of preserving life at all cost.

There are also important interfaces between the three main factors (Figure 1).

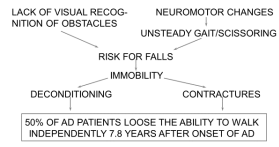

Mobility

is important for both participating in activities and decreases the risk of medical conditions; pneumonias and urinary tract infections [44]. Therefore, it is important to maintain mobility for as long as possible. The two main causes of walking difficulties caused by dementia are failure recognize obstacles and neuromotor changes (Figure 5) [45].

Figure 5: Causes of walking difficulties in persons with dementia

Walking could be maintained longer if residents with dementia have a safe environment to walk in and appropriate assistive devices. One useful device is a Merry Walker, that provides the ability to sit down when the resident is tired and has a strap that prevents falls [46].

Comfort

Interface between medical conditions and psychiatric and behavioral symptoms of dementia consist of comfort considerations. It should be recognized that even a simple medical intervention, e.g., obtaining blood sample, can cause discomfort in person who does not understand the procedure or its necessity. The discomfort caused by this intervention may lead to increased behavioral problems, mainly rejection of care that may escalate into combative behavior. Therefore, a balance between benefits and burdens should be always considered and medical interventions should be limited to those which are important for reaching the goals of care.

Comfort cannot be achieved in somebody who has pain. Although pain is not the main symptom of dementia, residents with dementia often have pain because of chronic conditions, e.g., arthritis, or because of intercurrent diseases, e.g., urinary tract infection [47]. Pain perception is not only diminished in Alzheimer’s disease but may actually be increased because patients perceive their pain for a longer time [48]. While neither stimulus detection nor pain threshold is correlated to cognitive status in Alzheimer’s disease, the vegetative response is lower in residents with more advanced dementia [49] but facial responses to noxious stimulation are increased when compared to cognitively intact individuals [50]. Very few if any residents with advanced dementia progress into a persistent vegetative stage [51] and, therefore, they can still perceive pain. More than half of the residents who were dying with advanced dementia experienced pain in the last week of life that was not satisfactorily managed [52,53].

Detection and diagnosis of pain in residents with advanced dementia is one of the most important factors in their quality of life. Nurses may feel uncertain about presence of pain in residents with dementia who could not report if they were in pain [54]. Patients with advanced dementia are less likely to have the ability to respond to pain scales, necessitating the use of observational scales in up to about half of patients [55,56]. One of the widely and easily used scales for detection of pain in non communicative residents is PAINAD [57].

Depressive symptoms

The interface between psychiatric and behavioral symptoms of dementia and meaningful activities are depressive symptoms. Depression is the most common psychiatric symptom in residents with dementia and it can be alleviated by meaningful activities [58]. Prevalence of depression increases with severity of dementia, reaching 42.5% in institutionalized residents with severe dementia, and is often under diagnosed and undertreated [59]. Symptoms of depression are related to both agitation [60] and rejection of care [61] and, therefore, successful treatment of depression improves quality of life of persons with dementia not only by improving their mood, but also by decreasing their stressful behaviors.

CONCLUSION

Quality of life for residents with dementia may be maintained despite ravages of the disease, by providing meaningful activities, treating behavioral symptoms, and managing the burdens and benefits of medical treatments. This framework can be used for holistic approach to management of problems affecting persons with dementia at all severity levels. However, it is mostly oriented toward residents with advanced dementia. There are several issues that are important for quality of life in mild and moderate dementia, e.g., driving, involvement in instrumental activities of daily living, and problem concerning family caregivers, which were not addressed in this review.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. Dementia, Fact sheet April 2016.

8. Manzar BA, Volicer L. Effects of Namaste Care: Pilot Study. Am J Alzheim Dis. 2015; 2: 24-37.

31. Wick JY. Infection control and the long-term care facility. Consult Pharm. 2006; 21: 467-480.

36. Bennett JA. Dehydration: hazards and benefits. Geriatr Nurs. 2000; 21: 84-88.