On an Overlooked and Falsifying Massive Theoretical Anomaly in the Eddington, Bending of Starlight by the Sun, Experiment

- 1. Independent researcher, retired from VITO, Belgium

Abstract

This publication critically examines the contemporary science (CS) paradigm surrounding the bending of starlight by the Sun’s gravity, emphasizing both the theoretical and experimental challenges in validating predictions from different CS models. It questions the fundamental assumptions of the CS framework, particularly the depiction of photons as being influenced by the Sun’s gravity (Newton’s law) to bend a star’s “ray of light.” The analysis revisits historical calculations of the bending angle, starting with von Soldner’s 1804 Newtonian estimate of 0.84 arcseconds, through Einstein’s predictions of 0.83 arcseconds (1911) and 1.7 arcseconds (1916), the latter based on general relativity. The publication also explores alternative models, such as Newtonian hyperbolic trajectory calculations and Euler method approximations. In addition, experimental limitations, such as atmospheric interference, are shown to compromise the precision of measurements, including Eddington’s 1919 eclipse observations, which were widely celebrated as validation of Einstein’s theory. It further exposes a significant, overlooked inconsistency: the paradox of photon acceleration under gravity, which conflicts with Einstein’s postulate of the constancy of light speed. The irrefutable anomaly in fact falsifies the Eddington paradigm itself. The text concludes that the prevailing CS paradigm, combining Newtonian and relativistic effects to explain light bending, requires re-evaluation, as it potentially misinterprets empirical phenomena and theoretical principles.

Keywords

• Eddington; Bending of Starlight; Gravitational Pull; Anomaly; Photon; Ray-of-Light; Paradigm; Falsification; Einstein’s Light Speed Postulate; Equivalence Principle.

Citation

Brauns E (2025) On an Overlooked and Falsifying Massive Theoretical Anomaly in the Eddington, Bending of Starlight by the Sun, Experiment. J Phys Appl and Mech 2(2): 1015.

INTRODUCTION

In contemporary science (CS), the concept of a star’s, so-called, ray-of-light bending due to the Sun’s gravity is associated with the 1919 Eddington solar eclipse experiment [1]. However, this paradigm can be falsified due to a significant theoretical anomaly that has remained unnoticed by CS for over 150 years. Despite photons being considered massless, CS persists in asserting that a “ray- of-light” from a star is bent by the Sun’s gravitational field. The CS “ray-of light” paradigm has already been irrefutably disproven in [2,3], and the findings in this publication (derived from section 12.13 in [2]) demonstrate that CS’s reliance on this model is fundamentally flawed. Instead, analyses should focus on the actual trajectories of photons in real space, emitted by the star in the distant past and arriving at the Sun’s location. Before addressing the falsification of the Eddington paradigm, it is crucial to first provide a detailed overview of the various gravitational approaches and calculations underlying CS light phenomena and gravity paradigms.

Historically, Newton hypothesized that light could bend under gravity, as he erroneously believed that light consisted of discrete material particles or “corpuscles” with mass-like properties. This assumption would have allowed Newton, in principle, to theoretically calculate the bending angle of light near the Sun using his gravitational laws. However, Johann Georg von Soldner was the first to perform such a calculation, publishing his analysis in 1804 (conducted in 1801) and determining a bending angle of 0.84 arcseconds for starlight near the Sun.

Einstein later theorized the bending of light rays using the equivalence principle in a thought experiment. However, since the CS “ray-of-light” paradigm was decisively falsified in [2,3], Einstein’s equivalence principle-based thought experiment is also invalid, as detailed in section 2.2. Section 2.3 presents an analytical solution based on Newton’s gravitational law. Using classic Newtonian orbit equations for a material object influenced by the Sun’s gravity, the resulting hyperbolic trajectory analysis yields a bending angle of 0.875 arcseconds.

As revealed in section 2.4 and in comparison, Einstein published in 1911 his linear ray-of-light based approach calculation of the bending angle of starlight by the Sun’s gravity, also based on Newtonian gravitational principles and arriving at a value of 0.83 arcseconds. In his paper, Einstein proposed measuring the 0.83 arcsecond bending angle of starlight during a solar eclipse, emphasizing the need for extraordinary experimental precision. To contextualize, a bending angle of 0.83 arcseconds corresponds to a deviation of only 0.00013% from a straight-line trajectory of 180° (648,000 arcseconds), highlighting the extreme accuracy required for such measurements on Earth during a solar eclipse.

It should be noticed that it was only in 1916 that Einstein published a second publication incorporating his relativity theory into his calculation, then yielding a total bending angle of 1.7 arcseconds. This value was derived by adding to his 1911 gravity-based calculation of 0.83 arcseconds a relativity-based contribution of the same magnitude, effectively doubling the bending angle. Measuring this minute 1.7 arcsecond deviation also required exceptionally high experimental precision, making conclusive results from the 1919 Eddington experiment inherently challenging. As discussed in section 3.1, the accuracy of Eddington’s measurements in 1919 likely fell short, casting doubt on their reliability. Nevertheless, the results were widely celebrated as proof of Einstein’s theory, catapulting those involved to fame. Retrospective analysis, however, acknowledges the inconclusive nature of Eddington’s findings, as noted in sources such as https:// www.physicsoftheuniverse.com/scientists_eddington.html (accessed February, 2025): “This verification of the bending of light passing close to the Sun (as predicted by relativity theory) was hailed at the time as a conclusive proof of general relativity, even if in retrospect the proof was actually far from conclusive.” Furthermore, section 3.2 reveals the existence of a significant hidden anomaly, invalidating not only the gravitational component of the bending angle but also the methodologies employed by von Soldner, Einstein and CS. Consequently, the Eddington experiment paradigm of a “ray of light bending due to the Sun’s gravity” is fundamentally falsified.

To complement the full overview of the different CS modelling approaches in section 2, an additional Euler based calculation of the bending angle is presented and analysed in section 2.5.

MODELLING METHODS TO DESCRIBE AND/OR CALCULATE THE BENDING OF STARLIGHT BY THE SUN

Bending of Starlight by the Sun’s Gravitation According to an Analysis by Von Soldner

Johann Georg von Soldner published in Germany in 1804 “Über die Ablenkung eines Lichtstrahls von seiner geradlinigen Bewegung” (Translation: “On the Deflection of a Light Ray from its Rectilinear Motion”) in the Berliner Astronomisches Jahrbuch, 1804, pp. 161-172 (1801). The English translation of his publication can be found at https://en.wikisource. org/?curid=755966 (accessed February, 2025). In that publication the detailed mathematical approach, as applied by von Soldner, can be found. The bending angle that von Solder calculated was 0.84 arcseconds.

Bending of light by the Sun’s gravitation on the basis of the equivalence principle

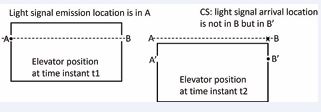

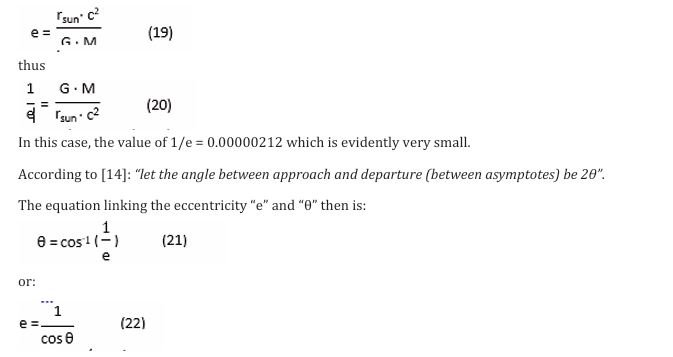

Chapters 9-11 in [2], and the related publications [3-5], conclusively refute the CS equivalence principle for photons, alongside other CS paradigms derived from light (photon) phenomena. Despite this, CS continues to endorse the representation in Figure 1, which attempts to explain the bending of light based on the equivalence principle.

Figure 1 Einstein’s bending of a ray-of-light in a gravitational field, thought experiment.

Einstein famously utilized a thought experiment involving a falling elevator to illustrate how the equivalence principle leads to light bending. In his scenario, an observer inside a freely falling elevator perceives the effects of gravity as indistinguishable from acceleration (velocity). If a horizontal light ray enters the moving elevator, CS claims that the observer inside the elevator would always observe the light to maintain its perfect horizontal trajectory inside the elevator, for whatever velocity of the elevator. This reasoning on the basis of the equivalence principle led Einstein to predict, in his 1911 publication [6], that light must bend in a gravitational field, a hypothesis that he suggested to test by observing the bending of starlight during a solar eclipse. While Einstein’s elevator thought experiment is not explicitly detailed in [6], it is frequently associated with his broader discussions of the equivalence principle, foundational to the development of special and general relativity.

CS, however, applies its interpretation of the equivalence principle in a simplistic manner, as depicted schematically in Figure 1. CS assumes that an observer inside an elevator, whether in free fall or moving at constant velocity, can use the CS equivalence principle and its simplistic “ray-of-light” paradigm to state that light travels as a perfectly horizontal ray from one wall opening to the opposite wall opening, regardless of the elevator’s velocity. The CS equivalence principle states: “The result of any local non-gravitational experiment, in a freely falling laboratory, is independent of the velocity of the laboratory, and its location in space. Thus, in a reference frame that is in free fall, the laws of physics are the same”. It can be noted that CS claims the validity of that equivalence principle for light phenomena (ray-of-light paradigm) in an elevator, as well in a laboratory on the surface of the Earth (since the Earth is in a free fall towards the Sun) and as well in the International Space Station (ISS) (since in a free fall towards the Earth).

The observer inside the elevator thus notes the presence of an opening A on the left wall and another identical opening B at the same height on the right wall. This observer, adhering to the CS framework, mistakenly concludes that light travels strictly horizontally as a “ray-of-light” from the hole A at the left to the hole B at the right within the co-moving reference frame of the elevator, regardless of the elevator’s velocity. However, since the elevator moves downward during the time interval Δt=t2−t1 that it takes for light to traverse from one side to the other, CS asserts (incorrectly) that the light will arrive at the hole in B′=B(t2). This claim, based on the CS ray-of-light and equivalence principle paradigms, leads to the erroneous conclusion that light thus must “bend”. CS proponents incorrectly argue that the light cannot follow the horizontal dotted line in Figure 1 to reach B(t1). These assertions are unfounded, representing fictitious constructs in their minds, disconnected from actual photon behavior in real space.

In contrast, as demonstrated in Chapters 9-11 of [2], and related publications [3-5], in real space a photon emitted from A(t1) will indeed travel along the dotted trajectory in Figure 1 to reach B(t1), and it will not arrive at B′=B(t2) as claimed by CS. It is also noteworthy that A(t2) is not the emission location of the photon; A(t1) was. The inconsistency in the CS type of reasoning is discussed in detail in [2-5]. The claim by CS that light bends due to gravity, based on forcing the photon’s arrival point to be B′=B(t2) using the CS equivalence principle, is therefore falsified. This view, still advocated by CS and its proponents, is purely expectation state-of-mind based and grounded in a simplistic and flawed CS ray-of-light paradigm that fails to save the real photon phenomena in real space. The correct view is represented by the “MF” effect described in [3], and illustrated in Fig. 9.12 in [2] (or Fig. 12 in [3]).

It is worth noting that while Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize for his work in [7], which established the existence of light quanta (photons), he did not incorporate photon behavior into his thought experiments. The CS reliance on the simplistic ray-of-light model in Figure 1 may stem from a then unknowingly/unintended/overlooked implementation of an infinite light velocity, which is evidently incorrect. Thus, the CS ray-of-light paradigm itself represents an “anomaly” within the thought experiment depicted in Figure 1. While the ray-of-light approach may serve as a useful and very good approximation for technical applications, it is fundamentally flawed and inadequate (inaccurate) for analyzing photon trajectories in fundamental research and thought experiments. Accurate analysis must consider photon trajectories in real space.

A dynamic representation EMDR008_E_Brauns_CS_Elevator_Obs1_Obs2.mp4 (based on the flawed CS views) can be downloaded at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/dv3bbhpb4h/1 (accessed February, 2025). From that same Mendeley Data Repository a consistent dynamic representation EMDR009_E_Brauns_True_Elevator_Obs1_Obs2.mp4 (based on the irrefutable scientific findings in [2-5]) can also be downloaded. In the mp4 representation EMDR008, CS claims erroneously on the basis of the equivalence principle that the light signal needs to be modelled as “AB” (time related in fact A(t1)-B(t2)) for the observer inside the moving elevator, for whatever value of the velocity of the elevator. In the mp4 representation EMDR009 however the irrevocable claim is made that the photon does not arrive in the location B(t2) but in the location B1=B(t1). In the dynamic representation the observer in the elevator thus does not observe the photon to arrive in B(t2) (the hole in the elevator wall at the right) but in the location B1=B(t1). The BB1 effect is akin to the MF effect discussed in [2,3] and represented by Fig. 9.12 in [2] (= Fig. 12 in [3]). The MF effect is the basis for the RVMD (Real Velocity Measuring Device) discussed in [2-5]. The CS falling (or moving) elevator thought experiment, used by CS to assert the bending of light based on the equivalence principle, is conclusively falsified. The CS equivalence principle paradigm is fundamentally flawed when applied to photons [2-5]. According to Thomas Kuhn [8] and Karl Popper [9], a scientific paradigm can be falsified by demonstrating the existence of an unresolvable anomaly that it cannot explain [8,9]. In [2,3], two such theoretical anomalies were identified, invalidating the simplistic and fundamentally flawed CS ray-of-light paradigm for use in fundamental research. It was shown in [2,3], that a photon cannot inherit any velocity vector component from its emission source, regardless of direction. This finding irrefutably falsifies the CS equivalence principle paradigm for photons. Furthermore, these theoretical anomalies led to the design and execution of a straightforward laser experiment [2-4], which provided experimental evidence against the CS ray- of-light paradigm and the equivalence principle for photons.

Additionally, section 3.2 presents further falsification based on a theoretical gravitational anomaly that CS overlooked for decades. This anomaly arises from the claimed gravitational pull on a “ray-of-light,” which directly contradicts Einstein’s postulate of the constant velocity of light. In fact, if a gravitational solar pull on a photon would exist, photons travelling in the direction of the Sun would accelerate and thus experience an increase of their velocity, in contradiction with Einstein’s second postulate claiming the speed of light to be constant. This contradiction invalidates the CS modeling approach for determining gravitational bending of light, as well as Eddington’s 1919 experimental validation of this concept during a solar eclipse.

A Theoretical Model Based on Newton’s Gravitational Laws to Calculate the Trajectory of a Photon Grazing the Sun.

In the CS literature addressing such analysis, it is assumed that the Sun’s gravity bends a “ray of light” as it grazes the Sun, adhering to Newton’s law of gravitational attraction. This assumption implies that the Sun’s gravitational pull affects not only material entities like planets but also light, thus photons. However, this raises significant questions, as it is difficult to reconcile how light, a non- material phenomenon, could exhibit mass-like properties and be influenced by gravity.

Newton’s corpuscular theory of light, which viewed light as consisting of material particles, was long ago discarded in scientific history. Even under the CS framework where light is conceptualized as a longitudinal electromagnetic wave, there is no theoretical basis to suggest that light possesses mass-like characteristics. Within the CS quantum paradigm, which describes light as being composed of photons, CS proponents might introduce speculative reasoning to attribute mass to a photon. Consequently, CS adherents might propose employing the Planck equation (1), invoking Planck’s particle-wave framework to describe photons and their behavior:

The CS proponents then could assume that Ephoton within the equation (1) could be converted by equation (2) in order to obtain:

This speculative equation (4) would enable CS proponents to assert that a photon possesses “mass,” thereby allowing them to “explain and claim” the Sun’s gravitational bending of a “ray of starlight” grazing the Sun. Newton’s law of gravitation-based light bending by the Sun is indeed discussed in CS literature, where proponents might reason as follows:

- a photon emitted by a distant star, thus originating very long ago from a far-off location, approaches the Sun

- as the photon nears the Sun, the gravitational pull exerted by the Sun intensifies, altering the photon’s originally linear trajectory into a “bent” orbital path. This bending culminates in the photon reaching its closest approach to the Sun at a specific moment.

- it is assumed that this closest approach corresponds to the photon grazing the Sun. This grazing point is further presumed to mark the midpoint of the photon’s trajectory. Consequently, the trajectory’s second half is expected to mirror the first half, forming a symmetrical, hyperbolic path.

- due to the photon’s high velocity, which exceeds the Sun’s escape velocity, the photon continues along its hyperbolic trajectory without being captured by the Sun’s gravity.

CS proponents might employ the mathematical framework of hyperbolic trajectories [10], modeled by a conic section expressed in polar coordinates, to support this reasoning:

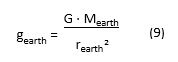

Obviously, for MEarth = 5.97219E24 kg and rEarth = 6.371E06 m one indeed obtains gEarth = 9.81 m/sec2. Regarding gSun, when implementing MSun = 1.98855E30 kg and rSun = 6.955E08 m, the value becomes gSun=274 m/sec², at the surface of the Sun. The gravitational acceleration gSun at the Sun’s surface is thus about 28 times higher than the gravitational acceleration gEarth at the Earth’s surface.]

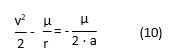

According to [10], one obtains an equation linking the velocity “v” of a particle in orbit and the value of “a” which is the semi-major axis of the orbit’s hyperbola:

One obtains from this equation the following equation expressing “a”, while replacing μ with G.M

The value of “a” is needed in the equations that follow, in order to calculate the eccentricity “e” value. When implementing:

rSun =the Sun’s radius = 6.955E08 m

M = the Sun’s mass = 1.98855E30 kg

one obtains a = 1474.59 m

The value of “a” already indicates the extremely small bending of the photon’s trajectory anticipated in the following calculations. Specifically, “a” represents the semi-major axis of the hyperbolic orbit, meaning that the distance between the grazing point and the intersection of the two asymptotes above that point is approximately 1.5 km. When compared to the Sun’s vast radius of 6.955E05 km, this amounts to a mere 0.0002 % of the Sun’s radius. Subsequent calculations will confirm the exceedingly small deviation of the actual hyperbolic trajectory from a straight line.

With the value of “a” determined, the next step is to calculate the value of “e” by incorporating the angular momentum “h” of the photon. At this stage, a CS proponent must acknowledge that if a photon lacks mass, it would also lack angular momentum “h,” rendering the analysis invalid. This realization would lead to the conclusion that the Sun’s gravity does not bend a photon grazing the

Sun. Nonetheless, CS proponents may proceed by assuming the angular momentum “h” is valid and incorporating it into the analysis [12,13]. The value of “h” is calculated by multiplying the speed of light “c” by the distance to the Sun’s center, which in this case is the Sun’s radius, as the “ray of light” is assumed to graze the Sun:

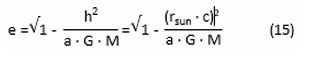

The equation for the eccentricity “e” then becomes:

When implementing the equation for “a” in this equation one obtains:

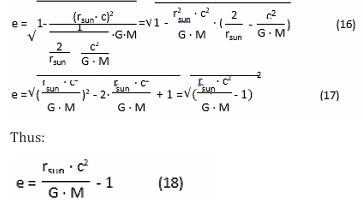

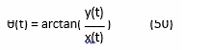

The value for the eccentricity “e” in this case of light grazing the Sun thus is e=471657. Obviously, one notices that the subtraction of “1” has a negligible effect on the value of “e”, thus here one can simplify the equation of “e” into:

Since 1/e is that small and very near to zero such means that θ is very near to π/2. Therefore 2θ is very near to π, meaning the trajectory is very near to a straight line.

The very small total bending angle α is therefore:

When implementing G, M, r and c, α in radians becomes α = 4.24035930410095 E-06. The many digits are shown in order to compare with the result from (24):

The small difference between both values results from the fact that arcsin(x)≈x for very small values of x, thus:

The value α = 4.24035930410095 E-06 (radians) from (23) then equals α = 0.875 arcseconds.

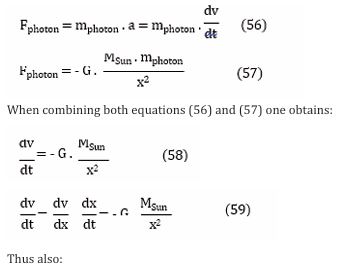

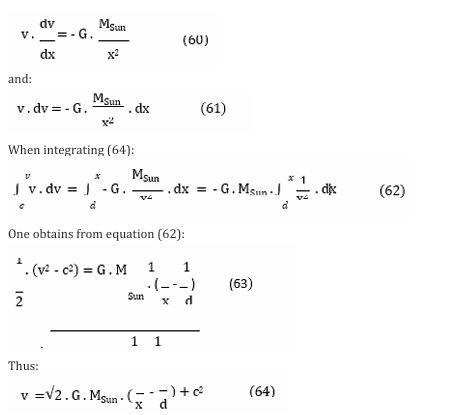

Einstein’s Gravity Based Approach in his First 1911 Publication in “Annalen Der Physik”

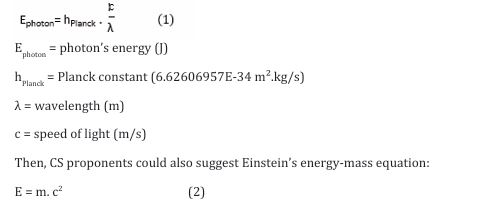

Einstein published his first “bending of light by gravity” paper [6] in 1911. Einstein did not implement his light quantum (photon) concept [7] in his analysis [6]. Instead, he introduced a Huygens light wave front based theoretical model, while “combining” that model with the CS ray-of- light paradigm (Figure 2a and Figure 2b) model.

Figure 2 a: Einstein’s Figure 2 model on page 907 in [6] based on a Huygens light wave front.

Figure 2 b: Einstein’s Figure 3 model on page 908 in [6] based on a “ray-of-light”.

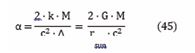

He concludes on page 907 of [6]: “Der Krümmungswinkel pro Wegeinheit des Lichtstrahles ist also”; meaning “The angle of bending per unit of travelling distance of the ray of light is thus”:

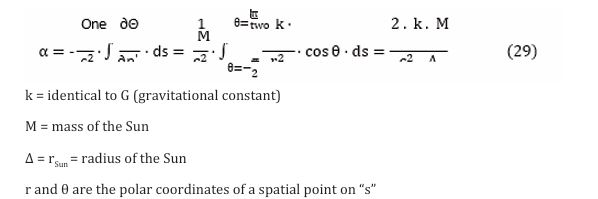

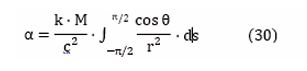

Einstein did not include the full integration in his paper, but explicitly exploring it is quite informative. Despite addressing a Newtonian gravity problem involving a non-linear trajectory, Einstein utilized a perfectly straight “ray-of light” line (refer to equation (33)) to compute the “bent trajectory” of that straight line. From a mathematical perspective, modeling a curved path using a straight line and then integrating along this straight line to determine the straight line’s bending is rather peculiar and unconventional. To substantiate this claim, here is the complete integration procedure he must have followed.

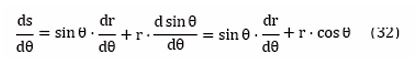

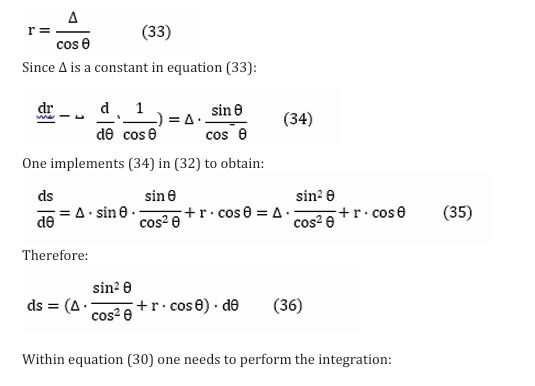

Figure 2b is clearly presenting the polar coordinates approach of a perfect straight line (see also equation (33)) and therefore:

s = r ⋅ sin θ (31)

On the basis of equation (31) one wants to perform the integration in equation (30) and therefore:

Since, from the perfect line in Figure 2b as assumed by Einstein with Δ (=rsun) being constant, one has:

This derivation makes it evident that Einstein in [6] could only have derived the result in equation (44) by assuming a perfectly linear trajectory (where Δ = rsun remains constant) (see also equation (33)) to calculate the “bending” of that straight line. This underscores the remarkable abstractions the human mind can devise. In this context, Einstein was “mathematically fortunate,” as explained further.

The result of the integration for the Sun bending a grazing ray of light is then:

Einstein’s result in equation (45) is “comparable” with the analytically (exact) obtained hyperbolic trajectory result in section 2.3, but is then only valid for very small values of ∝:

Einstein’s calculation relies on a straight-line “s” for his integration to determine the bending of a straight line, rather than employing an exact analysis that considers a curved trajectory. In the exact analytical hyperbolic trajectory case (section 2.3), the deviation from a straight trajectory is incorporated from the outset, yielding the precise hyperbolic solution. Similarly, the Euler approach (section 2.5) accounts for the cumulative deviation from a straight-line trajectory in its calculations. Notably, the exact analysis preserves the full arcsin term (section 2.3) in equation (46), whereas Einstein’s 1911 approach of course does not contain this arcsin term in equation (45). However, because the arcsin of a small value is nearly equal to the value itself, the resulting difference is negligible, leading to comparable ∝ values. If the bending angle had been much larger, the discrepancy in Einstein’s “straight ray-of-light” integration would have been more apparent.

On page 908 in [6], Einstein writes “Es wäre dringend zu wünschen, dass sich Astronomen der hier aufgerollten Frage annähmen ...Denn abgesehen von jeder Theorie muss man sich fragen, ob mit den heutigen Mitteln ein Einfluss der Gravitationsfelder auf die Ausbreitung des Lichtes sich konstatieren lässt.” (Translation: “It is highly recommended for astronomers to look into this ... the question should be raised if it would be possible to verify the bending of light with contemporary measuring instruments”).

Thus as early as 1911, Einstein suggested investigating the possibility of measuring the very small bending effect of light. However, he expressed skepticism about the sensitivity of the instruments available at the time to detect such small effects. Einstein proposed measuring the Sun’s gravitational bending angle of 0.83 arcseconds for starlight passing near the Sun during an eclipse. Plans for such experiments were indeed underway before Eddington’s famous solar eclipse mission in 1919: however a 1912 Argentinian solar eclipse mission in Brazil failed due to poor weather while a 1914 German solar eclipse mission in Crimea failed because of the outbreak of war and the temporary arrest in Crimea of the scientists involved, suspected of espionage. These events raise intriguing questions about how the history of science might have changed if these missions had gone ahead. The measurements would then have aimed to confirm Einstein’s 0.83 arcseconds bending angle, as published in his 1911 paper [6]. Had these missions succeeded, the trajectory of scientific discovery might have shifted significantly, as discussed in sections 3.1 and 3.2. Those measurements in 1912 and 1914 would have occurred before Einstein published his second paper in 1916 [15], in which he thus afterwards claimed a bending angle double that of his original 1911 prediction.

An Euler Method based Approximation of the Hyperbolic Orbit, as can be Conveniently Calculated, also in Excel.

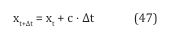

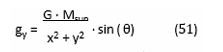

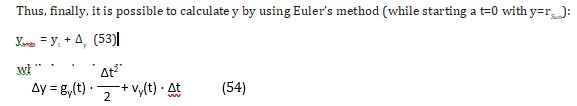

In Section 2.3, the hyperbolic trajectory of a photon was calculated using classical orbital equations derived from Newton’s laws of gravity, assuming the photon has mass and is therefore influenced by the Sun’s gravitational pull. This assumption leads to a slightly curved path rather than a straight line, with the trajectory’s incoming and outgoing segments forming asymptotes at an angle of 0.875 arcseconds. This trajectory can also be simulated mathematically using the Euler method in Excel. To set this up, one places the Sun’s center at the origin (0,0) of an (x,y) coordinate system and positions a photon at (0, rSun), moving horizontally at the speed of light, perpendicular to the y-axis. The assumption of mass is essential for the Sun’s gravity to exert a force on the photon, drawing it toward the Sun’s center and enabling the computation of the trajectory traj(x,y)=f(t) under gravitational influence. The gravitational force vector can be decomposed into horizontal and vertical components. A CS proponent emphasizes the vertical gravitational pull on the photon along the y- axis, while disregarding the horizontal pull in order to avoid a paradoxical outcome (discussed in detail in Section 3.2) that arises if horizontal forces are considered in the analysis. By focusing solely on the photon’s horizontal displacement at the constant speed of light c, the CS adherent can simplify the model through Euler calculations. To achieve this, the CS adherent introduces the following equation:

To calculate each new xt+Δt value in the series from the preceding xt value using this straightforward equation (47), one selects a time step interval Δt. For instance, Δt=0.01 s can be used when applying the Euler method and Newton’s law of gravity to calculate the photon’s position traj(x,y)=f(t). A sufficiently small-time step Δt ensures accuracy. In Excel, time values are stored in the first column, beginning at t=0 and incrementing by 0.01 seconds. The simulation showed that a total simulation time of 12.5 seconds was adequate to achieve the final bending value of approximately 0.875 arcseconds. The second column in Excel contains the x-values calculated using equation (47), representing the x-coordinates of the photon’s position traj(x,y)=f(t).

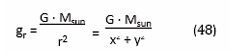

The y-values corresponding to the photon’s position on the trajectory are also calculated. The vertical component of the Sun’s gravitational force has the most significant effect on the photon’s deflection from a straight path. This force creates an acceleration directed toward the Sun’s center, which depends on the distance r between the Sun’s center and the photon’s position traj(x,y)=f(t). The relationship is described by the following equation:

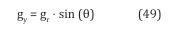

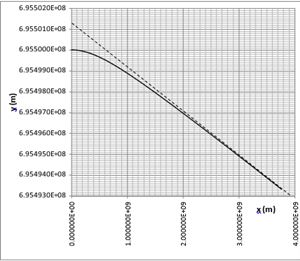

Within the Euler method approximation it is assumed further that during the very small Δt=0.01 sec time step linked to the movement of the photon of one trajectory location traj (x,y)=f(t) to the next location (x+Δx,y+Δy)=f(t+Δt) the value of gr is constant. One can calculate Δy by calculating first the vertical component of gr :

Notice that the Cartesian coordinate system (x,y) is linked to the polar coordinate system (r, θ). The value of θ can be obtained from the value of the photon’s momentarily location (x,y): y(t)

The value of θ is stored in an Excel column.

[Remark: in order not to run into a “division by zero” problem (see further) within the very first calculation step when determining θ at t=0 a value it is necessary to adequately use any very small value for the first value of xt=0 in the column of x; e.g. xt=0 = 0.0001 m.]

The values gy are stored in an Excel column.

Given the assumption that gravity at the photon’s location traj(x,y)=f(t) remains locally constant at each time instant, the vertical component of the photon’s “free-fall” velocity vector can also be calculated. It becomes evident that the photon’s motion is essentially a “free fall” within the Sun’s gravitational field, which shapes its trajectory, resulting in the observed hyperbolic path. Accordingly, the classic equation for the vertical velocity component vy can be implemented:

Δvy = gy(x,y) ⋅ Δt (52)

Since vy = 0 at t=0 one can calculate vy(x,y)= vy(t) at each time instant by applying Euler’s approach, thus by adding Δvy to the previous value vy(t) in order to obtain the next local value vy(t+Δt). In that manner the accumulating values for vy(t) are obtained. The calculated values of vy are stored within an Excel column.

As a result, the Euler method simulates the values for x and y of the photon’s trajectory traj(x,y)=f(t).

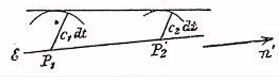

From the graphical representation in Figure 3 of the simulated hyperbolic trajectory, the bending angle α can be determined by extending and drawing the asymptote of the hyperbola (shown as a dotted line). Due to the large disparity in scale between the x-axis and y-axis in Figure 3, this scaling adjustment provides a clearer visual representation of the bending, which would otherwise be imperceptible. The angle β (= α/2) between the asymptote and the x-axis is then calculated by determining the inclination of the asymptote. This is done by identifying the coordinates of the two points where the linear asymptote intersects the x-axis and y-axis.

Figure 3 Simulation of the photon’s trajectory on the basis of the Euler approach.

This resulted in:

So:

β = 2.1146E-06 radians = 1.2116E-04 degrees = 0.436 arcseconds Thus the total bending angle α is:

α = 2 x β = 0.872 arcseconds

The Euler method, applied within Excel, thus approximates very well the result of 0.875 arcseconds as obtained in

section 2.3. Again: this is based on a CS proponent’s assumption that a photon has mass.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Eddington’s 1919 Solar Eclipse Expedition to Measure the Bending of Starlight

In 1911, as detailed in section 2.4, Einstein published his first calculation of the light-bending angle, arriving at a value of 0.83 arcseconds. This calculation was fully based on Newtonian gravity and relied on a peculiar integration method along a straight “ray-of-light.” The resulting approximation in equation (29) matched the analytical equation (23) due to the coincidence that, for small angles, arcsin(x)≈x. As explained in section 2.4, two solar eclipse missions to measure that light- bending angle of 0.83 arcseconds failed: a 1912 Argentinian mission in Brazil failed due to poor weather while a 1914 German mission in Crimea failed due to the start of the first world war 1914- 1918.

By 1916, Einstein published a revised calculation, doubling the predicted light-bending angle from 0.83 arcseconds to 1.7 arcseconds [15]. This updated value incorporated both Newtonian gravity and his general theory of relativity, accounting for the additional curvature of space caused by the Sun. In 1920, in appendix 3 of the third edition of his 1916 book, Einstein indeed explained that half of this deflection was due to Newtonian attraction and the other half to spacetime curvature, stating: “It may be added that, according to the theory, half of this deflection is produced by the Newtonian field of attraction of the Sun, and the other half by the geometrical modification (“curvature”) of space caused by the Sun.”: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:Relativity_(1931).djvu/173 (accessed February, 2025).

An eclipse mission to Venezuela in 1916 didn’t go through as a result of the war. An American eclipse mission in 1918 did not produce conclusive measurements. Finally, two British expeditions in 1919 succeeded in taking measurements during a solar eclipse. Crommelin led an expedition to Sobral, Brazil, while Eddington’s team observed from Principe Island, Spanish Guinea [16].

Eddington’s solar eclipse mission in 1919 made Einstein and Eddington famous instantly. It was hailed worldwide as the proof of Einstein’s relativity theory and most only know about Einstein’s 1916 publication and the 1919 Eddington mission. Many publications have been written about the Eddington mission, including scientific doubts about the quality of the measurements. Since the bending angle to be detected was that small it seems that the scientific consensus nowadays is that the quality of the measurement data was insufficient to be conclusive, as indicated explicitly in section 1.

Paul Marmet, a Canadian professor and PhD in physics, highlighted these issues in his paper “Relativistic Deflection of Light Near the Sun Using Radio Signals and Visible Light”. He argued: “This paper shows how all experiments claiming the deflection of light by the Sun are subjected to very large systematic errors, which render the results highly unreliable and proving nothing”:

https://www.newtonphysics.on.ca/ (accessed February, 2025)

https://www.newtonphysics.on.ca/einstein/appendix2.html (accessed February, 2025).

Paul Marmet points to the specific experimental problems and the poor quality of the eclipse data. He mentions the effect of atmospheric turbulence: “Rare is the night when any telescope, no matter how large its aperture or perfect its optics, can resolve details finer that 1 arc second. More typically at ordinary locations is 2- or 3-arc second seeing, or worse”. He thus states: “How could Einstein and Dyson claim to observe that, if at best their precision due to atmospheric turbulence in daytime heat was several arcseconds?”. One can also read about his other arguments, questioning the accuracy during Eddington’s eclipse measurements.

In [2] it is also explained in detail that, for accurate measurements of the Eddington type, it would be required to incorporate in the analysis the effect of the Earth’s RVV (Real Velocity Vector) and thus the use of a RVMD [2-5]. Including the Earth’s RVV value as a factor in the model during the analysis of the “bending measurement result” of the light signal (photon) trajectory has not been done but would be crucial. Also this missing part in the analysis needs verification to assess the possibility of a total misinterpretation by CS proponents regarding the so-called “bending” of starlight phenomena in solar eclipse effect measurements. Additionally, and as a decisive falsification of the CS approach regarding the derivations in section 2 of the bending angle of starlight by the Sun, by applying Newton’s gravity laws, a massive hidden theoretical anomaly is discussed in section 3.2. The oversight of that massive anomaly, present even in Einstein’s calculations, suggests that a comprehensive re-evaluation of all theoretical and empirical approaches to the bending of starlight is needed.

Falsification of all, Newton’s Gravity Laws Based Starlight Bending by the Sun, Calculations Supported by CS Proponents and the Resulting Consequences for CS

It is now evident and critically important to recognize that Einstein’s initial derivation and calculation of starlight bending by the Sun, published in 1911 [6], relied on Newtonian gravitational principles to estimate a light-bending angle of 0.83 arcseconds. Even in his 1916 publication, Einstein attributed half of the calculated bending angle to Newton’s classical gravitational effect, with the remaining half explained by his general relativity theory. This division is explicitly confirmed in his own writings, as quoted in Section 3.1. The attribution of the first half of the bending angle to Newtonian gravity assumes that photons possess mass and can thus be influenced by the Sun’s gravitational pull. Consequently, if this assumption were incorrect, all prior calculations and conceptual frameworks in section 2 would collapse into a meaningless virtual construct, only existing in the minds of the CS proponents, but without any correspondence to the real-world behavior of photons and thus not saving the real photon phenomena. If a photon has no mass, it would of course not be subject to Newton’s gravitational pull by any celestial body, including the Sun. The gravitational part of the bending angle, based on Newton’s gravity laws, would be meaningless. This would undermine the goal of measuring a total bending angle of 1.7 arcseconds during solar eclipse missions, as the foundational premise would be flawed.

To challenge the assumption, still upheld by CS proponents (January 2025), that photons have mass and are gravitationally pulled by the Sun, consider the following thought experiment. A photon is traveling in RS towards the center of the Sun, starting at time t=0 from a distance of 1 AU (Astronomical Unit; 149,597,870.7 km or 92,955,807.3 miles). According to Einstein’s second postulate, the speed of light is a constant, 299,792,458 m/s. However, in this scenario, if the photon is subject to the Sun’s gravitational pull, as claimed by CS proponents to explain light bending, the photon’s velocity should increase as it approaches the Sun. This implication directly conflicts with Einstein’s postulate of the constancy of the speed of light. From a qualitative perspective, the claim introduces a paradox: if photons are gravitationally accelerated toward the Sun, their speed would necessarily increase, violating Einstein’s second postulate.

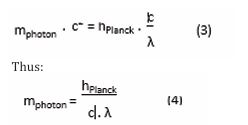

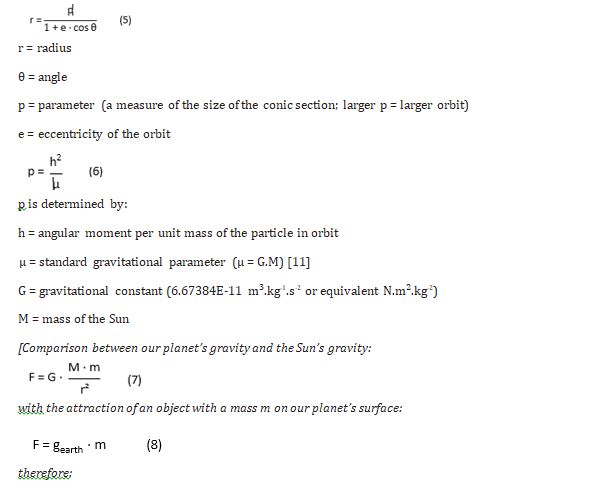

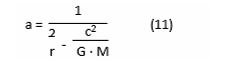

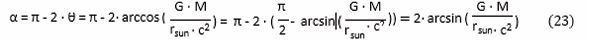

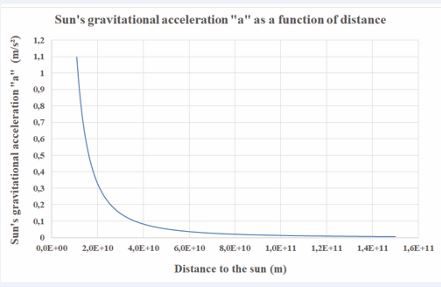

Quantitatively, the paradox can be modeled using Newtonian gravitational laws, which state that the gravitational acceleration depends on the distance between the object and the Sun’s center. As shown in Figure 4, the gravitational acceleration increases sharply near the Sun, reaching a peak of 274 m/s² at the Sun’s surface. Under CS reasoning, the photon would experience continuous acceleration, causing its speed to increase as it approaches the Sun. To quantify this inconsistency, one could establish a differential equation describing the photon’s velocity as it “falls” toward the Sun. By defining an x-axis with the Sun’s center at x(0) and the photon’s emission point at a distance d (1 AU) at x(d), the photon begins its trajectory along the x-axis towards the Sun’s center with the speed of light, c. Along its path toward the Sun, the gravitational pulling force Fphoton acting on the photon at a position “x” can be modeled using Newton’s equations:

Figure 4 The Sun’s gravitational acceleration “a” as a function of distance.

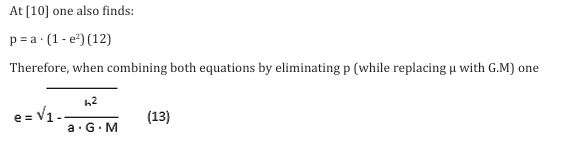

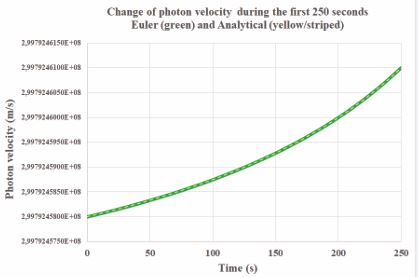

Equation (64) allows CS proponents to calculate the increase in a photon’s velocity due to the Sun’s gravitational pull during its trajectory toward the Sun’s center, starting from the moment it is emitted from a source located at x(d). As an additional validation, the Euler method was first applied to provide an initial approximation of the photon’s velocity increase. Figure 5 illustrates the impact of the Sun’s gravitational pull (as asserted by CS proponents) on the photon during the first 250 seconds of its “free fall” toward the Sun. The figure demonstrates that after 250 seconds, the photon’s velocity increases at an accelerating rate, as the decreasing distance between the photon and the Sun amplifies the gravitational pull, further boosting the photon’s acceleration. The calculation using the analytical equation (64) produces an identical curve (striped curve in Figure 5), confirming the consistency of the analysis.

Figure 5 The change of the photon’s velocity during the first 250 seconds.

Figure 5 exposes a significant theoretical anomaly that was overlooked by CS and its proponents. This undeniable evidence of such a major anomaly demonstrates that the CS paradigm concerning the bending of light, specifically, the deviation of a photon’s linear trajectory in RS due to gravity, must be regarded as fundamentally falsified (Popper’s falsification by anomaly principle in [9]). As a result, CS proponents are obliged to re-evaluate the flawed “ray-of-light” bending paradigm, including Einstein’s derivation in Section 2.4 and Eddington’s solar eclipse measurements, which aimed to confirm a bending angle of 1.7 arcseconds. It is now evident that half of this target value is fictitious. The conclusion is unequivocal: the assumption by CS proponents that a photon has mass and is subject to celestial gravity, such as that of the Sun, is incompatible with Einstein’s second postulate and must be considered falsified. This falsification carries profound implications across other areas of physics and astronomy. CS models related to light phenomena and their purported gravitational effects must undergo a comprehensive reassessment. In connection with the falsification proof of the equivalence principle for photons in [2,3], it can be additionally mentioned that artificial intelligence confirms this proof, as explained in detail in [17].

CONCLUSION

The modeling and description of light phenomena during the history of science was based on many different paradigms. From Newton’s corpuscular material light particles concept and the Huygens wave concept for light to Maxwell’s electromagnetic wave theory and Plank’s light quanta to the dual quantum theoretical particle-wave character. This gave rise during the history of science to the emergence of many CS (contemporary science) paradigms such as the CS ray-of-light paradigm and the CS paradigm of the bending of such a ray-of-light by gravity. Regarding the Eddington solar eclipse experiment in 1919 for measuring the bending of light by the gravity of the Sun, several scientific publications already reported on the inconclusive nature of the measurement results, as obtained during the Eddington mission. In this publication, moreover, the existence of a hidden anomaly in the modeling by CS of the bending of light by gravity is irrefutably proven. That anomaly contradicts Einstein’s second postulate of the speed of light to be constant. This unnoticed but irrefutable anomaly therefore undermines and falsifies the theoretical models that were used to determine the angle of bending of a ray-of-light by the gravity of the Sun and therefore also the Eddington related CS paradigm. CS must therefore completely revise the latter and in fact, multiple other CS paradigms based on light phenomena.

REFERENCES

- Dyson FW, Eddington AS, Davidson C. A Determination of the Deflection of Light by the Sun’s Gravitational Field, from Observations Made at the Total Eclipse of May 29, 1919. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 1920; 220: 571-581.

- Brauns, E. A Shattered Equivalence Principle for Photons - The Future History of the Falsification of Multiple Paradigms in “Exact” Science. 2024.

- Brauns E. On two thought experiments revealing two massive theoretical anomalies, proving both the contemporary “ray of light” paradigm to be flawed and the impossibility of a photon to inherit any velocity vector component from its source. Optik. 2021; 230: 1-12.

- Brauns E. On a straightforward laser experiment, confirming the previously published irrevocable falsification of the Equivalence Principle paradigm for photon phenomena. Optik. 2021; 242: 1-15.

- Brauns E. On the concept and potential applications of a photons-based device, measuring the velocity vector of an object, moving at high speed in space. Results in Optics. 2023; 10: 1-2.

- Einstein A. Über den Einfluss der Schwerkraft auf die Ausbreitung des Lichtes. (On the influence of gravitation on the propagation of light”.). Annalen der Physik. 1911; 4: 898-908.

- Einstein A. Über einen die Erzeugung und Verwandlung des Lichtes betreffenden heuristischen Gesichtspunkt. (On a heuristic point of view about the creation and conversion of light), Annalen der Physik. 1905; 6: 132-148.

- Kuhn T. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Second edition. The University of Chicago Press. 1970.

- Popper K. The Logic of Scientific Discovery, Routledge. Oxfordshire. 2002.

- Wikibooks contributors. “Astrodynamics/Orbit Basics,”. Wikibooks.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Standard gravitational parameter,” Wikipedia. The Free Encyclopedia.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Angular momentum,” Wikipedia. The Free Encyclopedia.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Orbit,” Wikipedia. The Free Encyclopedia.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Hyperbolic trajectory,” Wikipedia. The Free Encyclopedia.

- Ginoux J-M. Albert Einstein and the Doubling of the Deflection of Light. Foundations of Science. 2021; 27: 1-22.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Eddington experiment,” Wikipedia. The Free Encyclopedia.

- Brauns E. On artificial intelligence confirming my falsification of Einstein’s equivalence principle, for photons. 2025; 1-12.