The Wave-Particle Dualism of Photons as Seen from an Informational Perspective

- 1. Department of Applied Sciences and Mechatronics, Munich University of Applied Sciences, Germany

Abstract

The paper deals with J. A. Wheeler´s proposal that each piece of reality owes its existence due to observation - an approach to physics which implies that all physical entities at their bottom are informational in character. Focusing on the double-slit experiment with photons, which is the key evidence for the wave-particle dualism of photons, the paper follows Wheeler´s observational approach and interprets this experiment as a question posed to nature. Considering how the enquiry regarding the wave-particle duality of photons is answered by nature, it is shown that experimental questions are being answered by nature in the form of spatiotemporal patterns of elementary observations (EOs) which are binary pieces of information, produced by the dissipation of energy. Working through this line of thought, Wheeler´s statements of “binary information gain”, “observer participance”, and the “impossibility of continuum idealizations of physical laws” are elucidated and connections to the Landauer Principle being made. It is further shown that the wave-particle dualism of photons involves a dilemma of incompatible forms of existence, a problem which can be resolved by a discontinuous form of photon propagation in which photons repeatedly materialize and annihilate while being forward-shifted in space by finite distances equivalent to half the photon wavelength.

Keywords

• Quantum measurement

• Energy dissipation

• Information gain

• Elementary observations

• Observer participance

• Continuum idealization

• Existence; Reality

Citation

Gerhard Müller J (2025) The Wave-Particle Dualism of Photons as Seen from an Informational Perspective. J Phys Appl and Mech 2(1): 1009.

INTRODUCTION

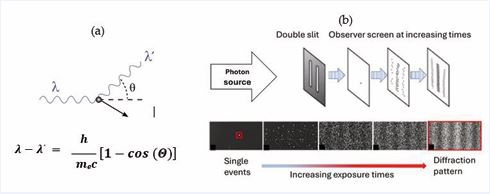

Throughout the history of science, the nature of light was an intensely debated subject that kept famous scientists busy over several centuries up to the present time. In the 17th century, i.e. upon the onset of modern science, two opposing views concerning the nature of light existed: while Isaac Newton [1-3], advocated a corpuscular nature of light, Christiaan Huygens [4], favored a wave like picture of light. This controversy turned towards an overwhelmingly accepted wave-nature of visible light when Thomas Young published the results of his interference experiments in 1807 [5]. Another piece of evidence in favor of the wave nature of light was the observation of Poisson spots [6,7], i.e. bright spots of light in the center of dark shadows of circular obstacles blocking off visible light sources. This general belief in the wave nature of light was shattered in the early 20th century when Max Planck [8], showed that the frequency spectra of the thermal radiation emitted from black-bodies could only be satisfactorily explained on the assumption that light is discussion, both experiments are sketched in Figure 1a,b. below (Figure 1).

Figure 1 (a): An X-ray photon of wavelength λ comes in from the left, collides with an electron at rest, and a new photon of wavelength λ′ emerges at an angle θ. The electron recoils, carrying away an angle-dependent amount of the incident photon momentum [10]. (b): (top row) Sketch of a double-slit experiment with photons (DSE), conducted for increasingly longer periods of time. Photon impacts on the detector screen feature as black dots which turn into increasingly denser patterns of black dots as time proceeds. After development of the photographic plates, the individual “photon impacts” appear as small, permanently whitened spots, approximating “diffraction patterns” in the long run [11].

(a): An X-ray photon of wavelength λ comes in from the left, collides with an electron at rest, and a new photon of wavelength λ′ emerges at an angle θ. The electron recoils, carrying away an angle-dependent amount of the incident photon momentum [10]. (b): (top row) Sketch of a double-slit experiment with photons (DSE), conducted for increasingly longer periods of time. Photon impacts on the detector screen feature as black dots which turn into increasingly denser patterns of black dots as time proceeds. After development of the photographic plates, the individual “photon impacts” appear as small, permanently whitened spots, approximating “diffraction patterns” in the long run [11]. While the Compton scattering experiments showed that X-ray photons can transfer momentum to an electron much as if two corpuscular pieces of matter had collided with each other [10], the double-slit experiment with photons (DSE) [11], indicated that travelling photons can freely alternate between particle- and wave-like motion within one single experiment. Following Einstein´s arguments [9], photons are emitted from the source in Figure 1b in corpuscular form and then proceed through open space in an undulatory manner until they hit the double-slit obstacle, where their motion becomes broken up into several streams of diffracted wave trains which finally interact with the detection screen. Once arrived there, the photons are absorbed in a corpuscular form, thereby producing seeming “particle impacts” with a spatial distribution characteristic of a classical diffraction pattern. Assuming that sharply localized particles and continuously distributed waves are primary forms of existence, the DSE leads to the dilemma of a wave particle duality of photons that embraces two mutually incompatible forms of existence. A further decisive step forward was taken in 1989 by John Archibald Wheeler [1], who asked the question of “How comes existence?”. In his seminal paper he proposed that every piece of reality owes its existence due to observation, an idea which he epitomized as IT from BIT. Reading through Wheeler´s paper, his view of an observation-based physics is no less mind-boggling than the more familiar concept of a wave-particle duality [12,13], as it deeply touches on the assumption of a pre- existing material world that exists independent of human existence. In order to reveal the mental challenges imposed by Wheeler´s approach, we simply quote the four main conclusions in his seminal paper [1] (1) The world cannot be a giant machine, ruled by any preestablished continuum physical law; (2) There is no such thing at the microscopic level as space or time or spacetime; (3) The familiar probability function … of standard quantum-mechanical theory provides a mere continuum idealization that conceals the information theoretic source from which it arrives; (4) No element in the description of physics shows itself closer to primordial than the elementary quantum phenomenon, i.e. the elementary device-intermediated act of posing a yes-no physical question and eliciting an answer or, in brief, the elementary act of observer participance. Otherwise stated, every physical quantity, every “IT”, derives its ultimate significance from “BITs”, i.e. binary yes-no indications, a conclusion which we epitomize in the phrase ”IT from BIT”. Wheeler´s ”IT from BIT” statement opened a controversial discussion confronting the innovative ”IT from BIT” vs. the more classical “BIT form IT” approaches [14-19]. In the following sections, we follow Wheeler´s general reasoning and apply his ideas to the well-researched and widely known example of light quanta passing through a double-slit diaphragm and detected by photographic means after their passage through the double-slit obstacle. By considering this specific example, we attempt to clarify Wheeler´s notions of “binary information gain”, “observer participance”, “continuum idealizations of physical laws”. Finally, we touch on Wheeler´s concepts of “existence” and “reality”.

THE DOUBLE-SLIT EXPERIMENT AS A QUESTION POSED TO NATURE

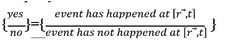

In this section, we follow Wheeler´s observational approach to physics and consider the DSE as an experimentally posed question to nature and ask ourselves how this question is being answered by nature itself. In order to proceed, we abandon here the interpretational pre-conceptions of “particle impacts” and “diffraction patterns” of the primary observables produced by the DSE and re-define them as informational entities. Turning to the seeming “particle impacts” on the photographs in the bottom row of Figure 1b and concentrating on the first picture on the left-hand side, only one single white spot in a black background can be observed. As this observation can neither be unequivocally attributed to a “particle impact”, nor to a “diffraction pattern”, the only unbiassed interpretation, possible at this stage, is that “an event had happened at the spacetime location

had been decided. As deciding a simple alternative, as for instance by tossing a coin, yields the minimum possible amount of information [20-23], the observation of a single bright spot may rightly be called an “elementary observation”, an “EO”, or simply a “quantum of observation” [24,25]. Referring back to Figure 1b, it is evident that the EOs are observables of a macroscopic size which can be observed either visually or at least with the help of an optical microscope, which implies that these

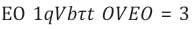

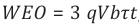

In this latter equation,

Processing in a sequential manner Nph photonsthrough the DSE, Nph EOs will emerge in small areas of size AEO, centered around positions

Ascreen. In this way, huge response matrices EO will emerge with NEO= Ascreen/AEO elements, where each element EOi,j counts the numbers of EOs that had appeared in the vicinity of

ELEMENTARY OBSERVATIONS AND “OBSERVER PARTICIPANCE”

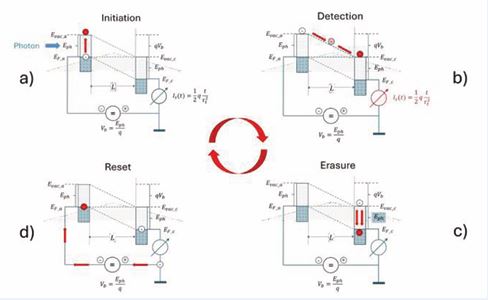

In the double-slit experiment of Figure 1b, the processed photons had been detected by photographic means with the aim of producing quasi-permanent, macroscopically observable EOs. As the photo-chemical processes involved in this technique are relatively complex, we return here to our previous work on photo-ionization detectors (PID) [27]. The reason for making this choice is that, firstly, the physics of PIDs can be easily overseen, and that, secondly, PIDs are able to perform as ideal photon detectors as explained in the textbook of Kingston [28]. PIDs, therefore, form ideal conceptual devices, which reveal how unobservable photon-detector interactions, occurring on the length scale of quantum phenomena, can be turned into macroscopically observable EOs [24,25]. Key motivation for considering such devices is elucidating Wheeler´s statement number 4, namely that

No element in the description of physics shows itself closer to primordial than the elementary quantum phenomenon, i.e. the elementary device-intermediated act of posing a yes-no physical question and eliciting an answer or, in brief, the elementary act of observer participance.

The principle architecture of a PID is shown in (Figure 2), in the form of a semiconductor-like band diagram, featuring two metal or semiconductor electrodes positioned face-to-face to each other in the form of a parallel-plate capacitor, with both electrodes having an electron work function of

Figure 2 shows Architecture of a photo-ionization detector (PID) as shown in the form of a semiconductor like band diagram. The four sub-figures indicate how a photoelectron, liberated from the photocathode on the left (Figure 2a), moves through the device, thereby creating a triangular current pulse Is(t) (Figure2b). (Figure2c) shows that upon termination of the current pulse, the energy Eph carried by the incoming photon and the kinetic energy Ekin= qVb=Eph , gainedbytheliberated photoelectron on its journey towards the photoanode, are both dissipated inside the photoanode and converted there into low-temperature heat. (Figure 2d),

Figure 2: Architecture of a photo-ionization detector (PID) as shown in the form of a semiconductor-like band diagram. The four sub-figures indicate how a photoelectron, liberated from the photocathode on the left (Figure 2a) moves through the device, thereby creating a triangular current pulse I(t) (Figure2b).(Figure 2c) shows that upon termination of the current pulse, the energy Eph carried by the incoming photon and the kinetic energy Ekin= qVb=Eph , gained by the liberated photoelectron on its journey towards the photoanode, are both dissipated inside the photoanode and converted there into low-temperature heat. (Figure 2d),

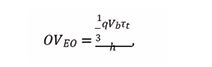

finally, shows that,upon termination of the current pulse, the energy Eph carried by the incoming photon and the kinetic energy Ekin= qVb=Eph , gainedbytheliberated photoelectron on its journey towards the photoanode, are both dissipated inside the photoanode and converted there into low-temperature heat. (Figure 2d), finally, shows that the thermalized photoelectron needs to be lifted back to the Fermi energy of the photocathode EF, a to enablea new round of photon detection. As already shown in our previous work [24,25], EOs are pieces of physical action, generated at the expense of generating entropy, and representing simple yes-no answers indicating whether a photon had interacted with the PID or not. In particular, we have shown that the EOs generated by a PID, can be characterized by two dimensionless figures of merit (FOM) with the first FOM signifying the observational value of the generated

The above-defined observables of EOs and matrices PEO are the principle forms of existence against which the mental constructs of “point-like particles”, “continuously undulating electromagnetic wave fields” or “photons” can be checked and whereby decisions can be taken whether these mental images do in fact mirror those pieces of reality that exist in a material world independent of any human existence.

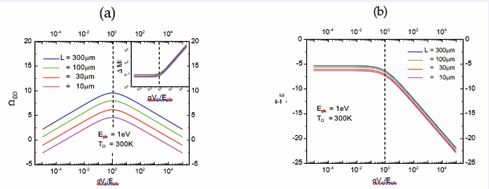

Figure 3a, b, in turn, plot the FOMs OVEO and SIEO , as normalized to the entropy that had been created inside the photoanode, as functions of the kinetic energy Ekin=qVb that had been imparted to the photoelectron on its journey from photocathode to photoanode. Figure 3a,b show that both FOMs take on optimum values at minimum entropic cost, in case both photon and detector share evenly in the energy expense of producing a macroscopically observable EO. This latter result clearly expresses the necessity of “observer participance” in generating macroscopically accessible “yes-no- indications” (Figure 3). (a) Observability ΩEO asa function of the normalized bias potential qVb ⁄Eph with the device size L as a parameter. The different curves in the inset show the impact of temperate on the entropy production; (b) Statistical significance ΣEO as a function of the normalized bias potential qVb ⁄Eph and as evaluated for different device sizes L. For clarity of presentation the curves in Figure 3b had been slightly offset from each other,

Figure 3 (a): Observability ΩEO as a function of the normalized bias potential qVb ⁄Eph with the device size L as a parameter. The different curves in the inset show the impact of temperate on the entropy production; (b) Statistical significance ΣEO as a function of the normalized bias potential qVb ⁄Eph and as evaluated for different device sizes L. For clarity of presentation the curves in Figure 3b had been slightly offset from each other.

Turning back to Figure 2, it is seen that a photon, which had initiated the formation of an EO in step (a), gets annihilated in step (c). In this step of annihilation, the energy Eph of the photon is broken down into pieces of size kBTD, i.e. the size of the mean thermal energy inside the detector. What is also evident from Figure 2c is that together with the photon energy EPh itself also the kinetic energy Ekin= qVb= Eph , thatthe photoelectronhadgained upon traversing the electrode gap, is also dissipated in step (c). Altogether, each bit of potential information [23], of size that the photon had carried prior to its detection, is thereby annihilated at the cost of dissipating an energy of size ELa ≥ 2 In (2) kBTD units of energy per bit of initially carried potential information. As argued above, the factor of 2 in Equation 7 originates from the fact that in addition to the photon energy Eph itself, the same amount of energy had to be invested in step b as well to make the unobservable photon-detector interaction in step a to become macroscopically observable. This additional energy demand is a clear sign of “observer participance” in eliciting “yes-no indications”. Further considering that Equation 7 represents the Landauer minimum energy cost for erasing a single bit of information [29-33], it is revealed that Wheeler´s statement of “observer participance” is simply another version of Landauer´s earlier statement of a minimum energy cost for annihilating bits of existing information [29-31].

SPATIAL PATTERNS OF EOS AND “OBSERVER PARTICIPANCE

The DSE had been designed to reveal whether a single photon propagates through a DSE in the form of a continuously undulating electromagnetic wave or as a corpuscular particle following a classical trajectory. As revealed from Figure 1b, experimental answers concerning the propagational behavior of a single photon do not emerge upon passage of a single photon but rather gradually evolve as increasing numbers of additional photons are sequentially processed through the DSE. In the limit of very large numbers of photons the form of the generated patterns of EOs ultimately take the form of “granular diffraction patterns (GDP)”. Recalling that the generation of each individual EO requires an observational energy expense of Eobs_EO≈ Eph , it is clear that the generation of a GDP is associated with an energetic burden of

where Ntrial counts the number of times a photon had been passed through the DSE. This latter burden is obviously orders of magnitude larger than the energy carried by a single photon, whose propagational behavior had initially been at the center of interest in in processing photons through a DSE. Returning to the series of photographs at the bottom of Figure 1b, these photographs suggest that in the limit Ntrial → ∞, the white dots, which represent the individual EOs, will merge and ultimately produce the image of a continuously varying probability density function PEO(x, y) , already introduced in section 2. As passing an infinite number of photons through the DSE and generating an equally large number of EOs requires an infinite amount of observational energy, which is practically impossible to supply, Wheeler´s first and third statements follow, namely the “impossibility of continuum idealizations of physical laws”. From the explanations above, it follows that this impossibility is an extreme form of “observer-participance” as the energetic cost of generating a GDP hugely overwhelms the cost of creating each individual EO inside this GDP.

In approaching the continuum limit of experimental answers, a second, DSE-specific problem arises through the merging of the white spots on the photographic detection screens shown in the bottom of Figure 1b. Through this merger, the illusion arises that photons propagating through a DSE perform this task in the form of classical electromagnetic waves – a result which seriously disagrees with the standard interpretation of the DSE which considers it as a key proof of the wave particle duality of photons. This latter results also clashes with Wheeler´s statement number 4 concerning the “primordial nature of binary yes-no indications”. Overall, this DSE-specific problem demonstrates that approaching the continuum level of physical answers may not always be the method of choice of providing physical evidence as important information might get lost in the process of eliminating granularity. With these remarks we leave the issues of “observer participance” and the “impossibility of continuum idealizations of physical laws” and touch on Wheeler´s other notions of “existence” and “reality”.

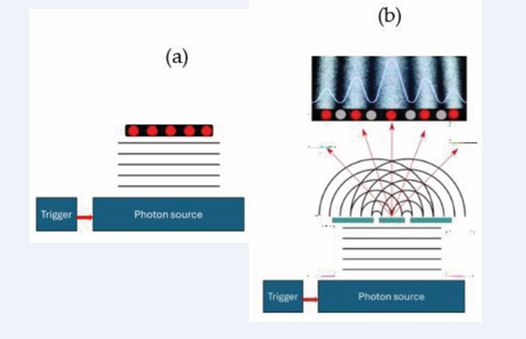

THE INCOMPATIBLE EXISTENCES OF WAVES AND PARTICLES

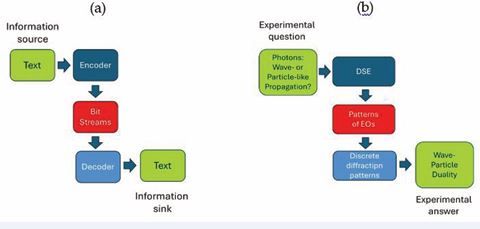

Section 2 has revealed that the elementary step in the process of experimental information gain is the generation of EOs, i.e. binary pieces of information, which in the long run evolve into response matrices PEO which represent the final experimental answers. This process of accumulating binary pieces of information into complete messages bears some resemblance to the technical process of communicating meaningful texts and images from an information source to an information sink in the form of meaningless binary digits [34,35]. Such a comparison is made in graphical form in Figure 4. As illustrated in Figure 4a, such a technical form of transmission requires a step of encoding at the source end, where human-understandable texts and images are encoded into bit streams, and a step of decoding at the receiver end, where the bit streams are re converted into human-understandable form again (Figure 4). (a) Comparison of a technical communication process; and (b) an experimentally posed question to nature concerning the propagation of photons through a DSE and eliciting an answer to the initially posed question. (Figure 4b), on the other hand, illustrates the process of information gain concerning the propagation of photons through a DSE. While the physical question is posed in verbal form in step 1, the answer is elicited, also in verbal form, in step 5. Looking back on the very long struggle between wave- and particle supporters of a theory of light, the initial question is asked in an either-or form, requiring a decision between the wave- and particle options of photon propagation to be taken in step 4 and to be verbally announced in step 5. Working from the initial step 1 to the final step 5, a translational step is required in step 2, in which the initial question is “translated” into the physical language of EOs to allow a macroscopically observable experimental answer to evolve in step 3. This task is effectively performed by the DSE shown in Figure 1b. As the construction of the DSE combines obstacles that are overcome with different ease in case a photon will choose the wave- or the particle option of moving through the DSE, distinctly different response matrices PEO will emerge at the end of step 3. As illustrated in Figure 1b, the patterns of EOs produced at this point, take the form of GDPs, i.e. a form that can neither be attributed to photons moving through the DSE in the form of continuously undulating electromagnetic waves, nor in the form of corpuscles continually following.

Figure 4 (a): Comparison of a technical communication process; and (b) an experimentally posed question to nature concerning the propagation of photons through a DSE and eliciting an answer to the initially posed question.

classical particle trajectories. As a consequence, the decision demanded in step 1 cannot be taken in step 4, and the expected result not be announced in verbal form in step 5. With the final message that photons in reality are neither waves nor particles, but maybe something as yet undefined in between, the narrative of the wave-particle duality of photons [12,13], had emerged. Looking at this situation from Wheler´s perspective, the failure of arriving at the requested binary decision between the wave- and particle pictures of photon propagation means that none of the alternatives addressed in step 1 can be endowed with the label of “existence”, which implies that neither photons moving along in the form of continuously undulating electromagnetic waves nor in the form of corpuscles continually following classical particle trajectories can be accepted as mental images of photons that do exist in reality in the outside material world. Overall, it appears that the process of information gain, depicted in Figure 4b, has resulted in a clear failure as the basic ontological question concerning the true nature of photons has been left unanswered at this stage.

AN ALTERNATIVE FORM OF WAVE-PARTICLE DUALITY

Drawing on the widely shared wisdom that “good questions produce good answers”, a re- iteration of the process in Figure 4b, is suggested. Carefully avoiding either-or alternatives, as in step 1 above, an initial question to start with in the re-iteration process could be: “Is it possible to devise a model of photon propagation through a DSE that incorporates in a single process elements of classical electrodynamic wave theory and of quantum mechanics, and that successfully reproduces the patterns of EOs produced at the end of step 3 ?”. In case such a model could be devised, there would be a clear match with the observations reported in Figure 1b, which allows a label of “existence” to be assigned to the GDPs displayed there. With this assignment in place, the mental construct of photons propagating in this innovative way could then be raised to valid mental images of photons travelling in reality in the outside material world. In order to arrive at such a modified form of photon propagation, we turn to the process of classical electromagnetic wave propagation. According to Maxwell´s equations [36,37], electromagnetic waves are propagated in a source-free environment, by a continuous interaction of local time-dependent electric

The solution of both coupled differential equations yields electrical and magnetic fields with amplitudes sinusoidally varying in x -and y -directionsandwithphases propagating into z – direction In these latter equations

Figure 5 (a): Spatial dependence of electric

c, (b) variation of the electromagnetic energy density (z , t) as a function of the propagational coordinate z , and as measured in units of the light wavelength

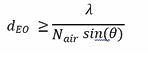

The transport of electromagnetic field energy through space is described by Poynting´s theorem [36,37], which yields for the electromagnetic energy density. This variation is plotted in Figure 5b. As u (z , t) varies quadratically with the electrical and magnetic field strengths, positive pulses of electromagnetic energy are repeatedly, but discontinuously being shifted along the positive z -axis with afinite step length of

(Figure 5). (a) Spatial dependence of electric

c, (b) variation of the electromagnetic energy density u (z , t) as a function of the propagational coordinate z , and as measured in units of the light wavelength

Any given volume V, filled with Nph photons, therefore will feel a pressure on its walls that directly scales with the numbers of photons trapped inside: i.e. prad ~ Nph . Returning to (Figure 5b), a new kind of wave-particle duality can then be envisaged: in this new picture, an electromagnetic wave starting out at z = 0 and at t = 0 with vanishingly small constituent field strengths will start out in the form of a space-demanding electromagnetic wave that propagates forward into z - direction. As this wave propagates it will generate an increasing radiation pressure onto those pieces of field energy that had originated from wave trains starting out at z = 0 but at times t < 0 . As these preceding pieces of electromagnetic field energy are already travelling at the maximum speed of light, the acting radiation pressure cannot enforce an acceleration onto the preceding electromagnetic wave packages towards higher speeds. The only escape from this increasing pressure dilemma is to transform increasing numbers of space demanding classical electromagnetic waves into much more compact and heavily localized light corpuscles, i.e. photons. Figure 5b shows that upon reaching the position

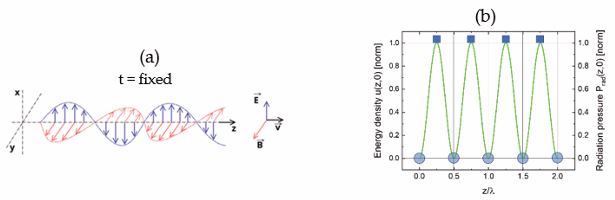

Figure 6 (a): Coherent light source launching plane electromagnetic waves towards a flat-plate absorber fitted with an array of photon detectors (red circles); (b) same kind of photon source launching plane electromagnetic waves towards an absorber pierced with two transparent slits. The ensuing emission of diffracted wave trains form an arrival pattern of photons on a downstream photographic screen. Colored circles indicate possible detector positions for tracing plane-wave propagation in (a) and non-uniform diffraction pattens of EOs in (b).

(a) Coherent light source launching plane electromagnetic waves towards a flat-plate absorber fitted with an array of photon detectors (red circles); (b) same kind of photon source launching plane electromagnetic waves towards an absorber pierced with two transparent slits. The ensuing emission of diffracted wave trains form an arrival pattern of photons on a downstream photographic screen. Colored circles indicate possible detector positions for tracing plane-wave propagation in (a) and non-uniform diffraction pattens of EOs in (b). Moving forward from freely propagating plane wave fields (Figure 6a) to situations in which obstacles such as double-slit diaphragms are inserted into the flow of plane-wave fronts (Figure 6b), planar wavefronts become disturbed by these obstacles through the classical process of wave diffraction. As illustrated in Figure 6b, the initially planar wave fronts thereby become split up into a number of diffracted wave fronts. In this event, streams of diffracted waves start to radiate out into different directions after the obstacle had been passed, giving rise to continuously distributed diffraction patterns. As in the proposed new scheme of photon propagation the co generated “corpuscular photons” will consistently follow the directions of the classical wave trains towards the downstream photographic detection screen, the wave guided photons will produce apparent “particle impacts” on the photographic screen with a spatial distribution corresponding to a “classical diffraction pattern”. In this way the observed kinds of GDPs, shown in Figure 1b, will arise. Unlike in the classical interpretation of the DSE, cited in the introduction, there is no longer a dilemma of a conversion between incompatible forms of existence of light, as the interconversion of light waves into photons and vice-versa has now become a periodic process deeply interwoven with the process of classical wave propagation. At this point, we note that the proposed new process of light propagation is consistent with Youngs classical interference experiments [5], on the one hand, and with Planck´s [8], and Einstein´s [9], quantum interpretations of light propagation, on the other hand. Returning to the process of experimental information gain sketched in Figure 5b the avoidance of an either-or question at the beginning and the assumption of a wave-particle duality, deeply interwoven into the normal process of electromagnetic wave propagation, removes the dilemma of photons of changing between two incompatible forms of existence on their way through a DSE. Needless to say at this point is that this proposition will require significant downstream scientific scrutiny to become finally accepted.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we have been following J.A. Wheeler´s observational approach to physics [1], and regarded the double-slit experiment with photons (DSE) [11], as a question posed to nature. Progressing along Wheeler´s line of thoughts, we have abandoned the interpretative preconceptions of the experimental outputs of a DSE as being “particle impacts” and “diffraction patterns” and re- interpreted them as informational entities residing at the primary level of physical existence.Discussing these primary forms of physical existence, we could clarify and elucidate Wheeler´s notions regarding “observer participance” in eliciting “binary yes-no indications” and the “impossibility of continuum idealizations of physical laws”. In particular, we could elucidate the following items:-

- Eliciting yes-no indications” is enabled by turning photon-detector interactions at the quantum level into macroscopically observable EOs,

- The “observer participance” in “eliciting “yes no” indications” arises out of the necessity of supplying extra energy on the observer side to turn unobservable, quantum-mechanical photon- detector interactions into macroscopically observable EOs,

- The “impossibility of continuum idealizations of physical laws” arises out of the excessive observational energy demand in eliciting infinite numbers of EOs.

- Whittaker’s notion of “observer participance” complies with “Landauer´s earlier statement of a finite energy demand of

Key enabling step in elucidating these items was analyzing the act of photon detection with the help of photo-ionization detectors (PID) [25-28]. Because of their easily overseeable physics and their ability to act as ideal photon detectors, PIDs appeared as useful conceptual devices to analyze the informational characteristics of photon-detector interactions. Still following Wheeler´s observational line of thought [1] , we touched in the final section on the physical concepts of “existence” and “reality”. There, we proposed an alternative interpretation of the DSE which is based on a new kind of discontinuous light propagation, in which light repeatedly and discontinuously alternates between “wave-like” and “particle like” motion with a finite step- length equivalent to half a photon wavelength.

Funding: This research did not receive institutional or public funding. Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applicable. Data Availability Statement: All relevant data are contained in the published text. Acknowledgments: The author thanks Professor Bormashenko for useful comments during the text preparation.

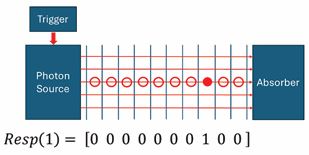

Conflicts of Interest: The author does declare “no conflicts of interest. Apendix A. Do Photons Travel Along Straight Lines ? After Planck [8], and Einstein [9], had proposed their photon hypothesis, the idea became popular that photons propagate through empty space along simple straight lines, similar to corpuscular particles moving through force-free environments. In this appendix we consider the example of a freely propagating photon and show how a discrete set of observations converges to the continuum limit of a simple straight line. Figure A1 sketches a thought experiment that could be used to test the proposition made in the headline. As shown there, a plane electromagnetic wave is launched from a photon source on the left and allowed to propagate towards a photon absorber on the right. As discussed in section 6, the photon source in Figure A1 can in principle be turned into a single-photon source by appropriately reducing.

Figure A1: A photon source, producing plane-wave fronts carrying photons, moving on parallel paths, from source to sink. Along the chosen line, a 10-detector array is positioned at regular positions with identical distances between detectors to allow photons to be detected as they move from source to sink. In the example above, a single photon travelling through the array is randomly absorbed at the eighth detector downstream to the source, thereby producing as an output signal a 10-element response vector with ZEROs at all positions, except for position 8.

the electric and magnetic field strengths Ex0 and Bx0 . In order to trace out the trajectories of photons emitted there, ten detectors are positioned along the imagined photon trajectory, with each detector being placed at equidistant positions

(Figure A1). A photon source, producing plane-wave fronts carrying photons, moving on parallel paths, from source to sink. Along the chosen line, a 10-detector array is positioned at regular positions with identical distances between detectors to allow photons to be detected as they move from source to sink. In the example above, a single photon travelling through the array is randomly absorbed at the eighth detector downstream to the source, thereby producing as an output signal a 10-element response vector with ZEROs at all positions, except for position 8.

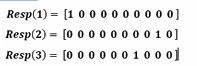

Starting with the experiment, we first send three photons sequentially through the array. In this way, three 10-element row vectors are produced with ONES at random positions:

Vector addition of all three responses produces a new 10-element row vector, resulting in an average number of response indications per sensor position of Eoav (3):

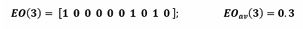

Repeating this process of passing photons and accumulating outputs, random vectors with increasingly larger natural numbers on all positions result and with relatively smaller statistical scatter between individual positions as the number of trials Ntrail is increased:

Normalizing the row vectors EO with regard to the number of photons Ntrial that had been passed through the array, it is easily seen that the numbers Eoav (Ntrial), converge to the quantum efficiency of each detector of

Figure A2 :(a) top curves: Numbers of accumulated EOs and their standard deviation with increasing numbers of photon passages Ntrial through the array; (b) same quantities as above but normalized to the numbers of photon passages Ntrial through the array.

(Figure A2). (a) top curves: Numbers of accumulated EOs and their standard deviation with increasing numbers of photon passages Ntrial through the array; (b) same quantities as above but normalized to the numbers of photon passages Ntrial through the array.

Recalling that an ideal approximation to a straight line is obtained when all entries for the individual detector positions are exactly the same, Figure A2 shows that this situation is attained in the case Ntrial→ ∞. Further recalling that for generating each individual EO an observer-related energy cost of Eph is involved, the observational energy response raises towards infinity, i.e. a result that underlines Wheler’s statement of the “impossibility of continuum idealizations of physical laws”.

REFERENCES

- Wheeler JA. Information, physics, quantum: the search for links. Proceedings III. International Symposium on Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. 1989; 354-358.

- Newton I. Opticks or, a treatise of the reflexions, refractions, inflexions and colours of light. Also, two treatises of the species and magnitude of curvilinear figures.1998.

- Sabra AI. Theories of Light, from Descartes to Newton. CUP Archive. 1981.

- Shapiro AE. Huygen´s “Traité de la Lumière and Newton’s ‘Opticks’:Pursuing and Eschewing Hypotheses”. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of The history of science. 1989; 43: 223-247.

- Joseph Johnson. A Course of Lectures on Natural Philosophy and the Mechanical Arts. Young Th, London 1807.

- Fresnel A. JO, Euvres Completes. Imprimerie impériale.1868; 369.

- Arago spot – Wikipedia. 2025.

- Planck M. On the Law of Distribution of Energy in the Normal Spectrum. Ann Phys. 1901; 4: 553

- Einstein A. Über einen die Erzeugung und Verwandlung des Lichtes betreffenden heuristischen Gesichtspunkt. Ann. Phys. 1905; 17: 132.

- Compton AH. A Quantum Theory of the Scattering of X-Rays by Light Elements. Phys Rev. 1923; 21: 483- 502.

- Meschede D. Youngs Interferenzexperiment mit Licht. In Die Top Ten der Schönsten Physikalischen Experimente Fäßler; Fäßler, A, Jönsson, C. Eds. Rowohlt Verlag. 2005; 94-105.

- Feynman RP. Lectures on Physics - Quantum Mechanics. Addison- Wesley, Reading, Massachusetts, Palo. 1965; 1-3.

- Landau LD, Lifshid EM. Quantum Mechanics Non-Relativistic Theory, 3rd ed.; Pergamon Press. 1977; 3: 46-49.

- Piccinini G, Maley C. Computation in physical systems. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2010.

- Lloyd S. The Universe as Quantum Computer, A Computable Universe: Understanding and Exploring Nature as Computation. 2013.

- Miller JF, Harding SL, Tufte G. Evolution-in-materio: Evolving computation in materials. Evol Intel. 2014; 7: 49-67.

- MarkovI. Limits on fundamental limits to computation. Nature. 2014; 512: 47-154.

- It From Bit or Bit from It? On Physics and Information; Aguirre, A. Forster, B., Merali, Z. eds.; Springer Verlag, Berlin Frontiers Collection. 2015.

- Quantentheorie: It from Bit. 2025.

- Shannon CE. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst Tech J. 1948; 27, 379-423.

- Ben-Naim A Dufour C. Information Theory-Part1: An introduction tothe fundamental concepts“. World Scientific. 2017.

- Ben-Naim A. A Farewell to Entropy: Statistical Thermodynamics Based on Information; World Scientific. 2008.

- Müller JG. Information contained in molecular motion. Entropy. 2019; 21: 1052.

- Müller JG. Events as Elements of Physical Observation: Experimental Evidence. 2024; 26: 255.

- Müller JG. Elementary Observations: Building Blocks of Physical Information Gain. Entropy Basel. 2024; 26: 619.

- Bormashenko E. Landauer Bound in the Context of Minimal Physical Principles: Meaning, Experimental Verification, Controversies and Perspectives. 2024; 26: 423.

- Müller JG. Photon Detection as a Process of Information Gain. Entropy Basel. 2020; 22: 392.

- Kingston RH. Detection of Optical and Infrared Radiation; Springer: Berlin Heidelberg. 1978.

- Landauer R. Irreversibility and heat generation in the computing process. IBM J Res. 1961; 5: 183-191.

- Landauer R. Information is physical. Phys Today. 1991; 44: 23-29.

- Landauer R. Minimal Energy Requirements in Communication. Science. 1996; 272: 1914-1918.

- Bormashenko E. The Landauer Principle: Re-Formulation of the Second Thermodynamics Law or a Step to Great Unification? Entropy. 2019; 21: 10-918.

- Witkowski C Brown S, Truong K. On the Precise Link between Energy and Information. Entropy. 2024; 26: 203.

- Young JF. Einführung in die Informationstheorie, R. Oldenbourg München, Wien. 1975.

- Kraus G. Einführung in die Datenübertragung. R. Oldenbourg Verlag: München; Wien. 1978.

- Nolting W. Grundkurs-Theoretische Physik 2 Elektrodynamik; Springer: Berlin. Heidelberg. 2013; Jackson JD. Classical Electrodynamics. John Wiley & Sons. 1975.

- Author 1A. Author 2B. Book Title, 3rd ed.; Publisher: 2008; 154-196.

- Kittel Ch, Physik der Wärme, R. Oldenbourg, München, Wien, John Wiley Sons. 1973.

- Radiation pressure - Wikipedia