Quantitative Analysis of Mental Wellbeing of fly-in fly-out Construction Project Support Service Workers

- 1. School of Medical and Health Science, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, Australia

Abstract

This study investigated the prevalence of psychological distress among fly-in fly-out (FIFO) support service workers at a remote construction project in Western Australia. A cohort of 113 employees volunteered from a population of 306 workers. Eight questionnaires were incomplete leaving 105 useable surveys for analysis (34.3% response rate). All participants completed the Kessler 10 Psychological Distress Scale (K10) including questions relating to a range of lifestyle factors. Data was compared against general population scores and the correlations for each of the K10 factors were calculated. Participants reported more instances of high or very high K10 scores (25.7%) compared to the general population (8.2%). The least popular coping methods during difficult times were “contact a medical professional” (1.9%) and “contact a mental health support group” (1.0%). More than half the participants (52.4%) reported being subjected to workplace bullying and harassment. Feeling socially isolated while on-site was strongly correlated with high K10 scores (r2= 0.61). FIFO workers in the support services are at risk of suffering mental health problems at work. Workers are reluctant to seek help regarding their mental health due to a fear of stigmatisation. Employers need to develop strategies and training aimed at building resilience, breaking down stigma and eliminating bullying among FIFO workers.

Abbreviations: FIFO: Fly-in Fly-out; DIDO: Drive-in drive-out; K10: Kessler 10 Psychological Distress Scale; WA: Western Australia; ECU: Edith Cowan University; EAP: Employee Assistance Program

Keywords

Mental Wellbeing , Support Services , Fly-In Fly-Out , FIFO , Kessler 10 , Psychological Distress , Construction Project , Bullying , Harassment ,Social Isolation

Citation

Sellenger M, Oosthuizen J (2017) Quantitative Analysis of Mental Wellbeing of fly-in fly-out Construction Project Support Service Workers. J Prev Med Healthc 1(1): 1001

Abbreviations

FIFO: Fly-in Fly-out; DIDO: Drive-in drive-out; K10: Kessler 10 Psychological Distress Scale; WA: Western Australia; ECU: Edith Cowan University; EAP: Employee Assistance Program

INTRODUCTION

During 2013/2014, the Western Australian (WA) resources industry employed 108 975 people, of which, an estimated 67 000 were in fly-in fly-out (FIFO) roles [1]. FIFO employment requires workers to live on-site for a pre-determined period of time in remote locations, interspaced with time off at home. Recently the mental wellbeing of FIFO workers has been the focus of attention in WA with media reports indicating that over a 12 month period between 2013/2014, there were nine suicides allegedly related to the FIFO lifestyle. The Education and Health Standing Committee of WA released a report “The impact of FIFO work practices on mental health” in which it was noted that the nine suicides that prompted the inquiry could not be identified. The committee also determined that there was no central body responsible for collating and processing reports on mental health or suicides in the industry and that the results of research in the area is inconclusive with some data showing higher and others lower prevalence of mental health issues [2].

A study of FIFO and drive-in-drive-out (DIDO) workers in Queensland of self-reported psychosocial wellbeing reported both positive and negative impacts on their family and social life, relationships, mood, work satisfaction, financial situation and sleep. Workers were aware of various on-site support programs and also formal and informal support such as on-site medics or trusted friends and colleagues who they could talk to. A number of barriers to help seeking were noted and many workers had difficulty recognizing their own stresses. Employee Assistance Programs alone are not sufficient in providing support for remote workers. Due to small sample size (n=11) more work is needed to explore these issues further [3].

Access for workers to good quality recreational facilities promotes social interaction and also provides an environment that supports improved social inclusion that improves workers wellbeing, fosters a sense of community and reduces alcohol consumption. Accommodation and infrastructure also should provide opportunities for individual privacy [4].

The focus of research has been on “mining or FIFO employees”, which is a very general classification. In order to support remote resources projects a wide range of services need to be provided. These include catering, accommodation and maintenance and they are often classified as “essential services” or “support services”. The companies and workers responsible for providing these support services are often overshadowed by workers involved in construction, mining or refinery processes yet they also contend with the same lifestyle factors and psychological challenges faced by their operational counterparts and often have worse work conditions in terms of status, remuneration, FIFO rosters (time spent on-site and off-site) and shifts times spread across day and night.

This research project focused specifically on a cohort of support service workers at an accommodation village that serviced the construction of a plant in the Pilbara region of WA. In early 2015, the village experienced the loss of a young worker who took his own life during his time off-site. His passing was not initially linked to his FIFO role and was not reported in the media, raising the question of how many suicides associated with FIFO are not reported or investigated at all [2]?

As far as could be established no previous studies of psychological distress among FIFO support service workers and the personal challenges they face in their workplace have been conducted. The primary objective of this project was to examine a specific cohort of support service workers within a large industry to assess their mental wellbeing as measured against the general population of WA. These findings could be used to inform the development of mental health interventions among this unique cohort of workers supporting the resources industry in WA

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

At the time of this study there were 306 workers employed in a role that met the inclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were;

• employed by the support services company at the remote accommodation village,

• experience in the role of at least 4 weeks,

• on a “4 weeks on-site, 1 week off-site” FIFO roster.

The workers’ job roles included, but were not limited to, catering, housekeeping, liquor and retail service, luggage handling, facilities maintenance, gardening, supply chain, and general cleaning

Eight information sessions were scheduled across a twoweek period at the workplace in order to recruit as large a sample as possible. The sessions provided information to the workers regarding the nature of the study and to inform them that the questionnaire would be sent out to their email addresses. Workers were given an opportunity to ask questions either in a public or private forum. Researcher contact details were provided, as well as details for an independent contact at Edith Cowan University (ECU). The researcher also provided contact details for the Employee Assistance Program (EAP) and several other public support groups in case participant(s) wanted to speak to somebody confidentially.

The workers were invited by email to participate by following a link to an external online questionnaire. The questionnaire included an information and informed consent page that requested the participants to provide consent and complete the questionnaire honestly and to the best of their ability

Anonymity

As a requirement of the ethics approval, participation was confidential and anonymous and this was explained during the information sessions, and in the invitation sent out by email and at the start of the survey. The questionnaire was completed online through Qualtrics Online Survey Software (Provo, Utah), which de-identified the responses before allowing the data to be accessible to the researcher. Due to the nature of the professional relationship between the researcher and the workers, the questions asked in the questionnaire were chosen specifically so that no worker could be identified by their responses. Types of questions not asked included the participant’s age and specific job role.

The Questionnaire

The questionnaire consisted of twenty-eight items and could be completed in approximately 5-10 minutes. The initial questions collected information on demographics, FIFO job characteristics, job satisfaction and lifestyle factors such as self-perceived health and fitness levels, alcohol and cigarette consumption, time spent exercising as well as sleep quality, major life events and coping methods. The final 10 questions incorporated the validated K10 as this is a scale used by the Australian government allowing for comparison with the general population [5].

The K10 explores levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms experienced over the previous 4 week period and it was designed as a standard measure of psychological distress. Items are rated on a score between 1 and 5. The sum of individual scores provides a potential score range from 10 to 50. A low score of between 10 and 15 is not considered to require any help. A medium score between 16 and 21 is considered as requiring some level of self-help. A score above 22 is considered to be an “at risk” level of psychological distress requiring self-help or professional help. A score above 30 is considered to be a very high level of psychological distress where the individual is considered to require professional help [6]. The K10 instrument has been previously validated [7] and it provides a straightforward approach to anonymous data collection on psychological distress.

Statistical Analysis

Data was collected from 29 July to 18 August 2015 and downloaded into Microsoft Excel 2010. The questionnaire was completed by 113 individuals, six responses were considered incomplete or spoiled and two were completed by workers who did not meet the inclusion criteria, leaving a total of 105 valid respondents (34.3% response rate). Individual factors were compared against the K10 scores and scatter plots were examined to identify trends. Kendall tau correlation was used to indicate relationship between K10 scores and methods for coping. Pearson correlation was used for the association between K10 and social isolation.

Ethics approval

The project was approved by the Edith Cowan University Human Research Ethics Sub-Committee and the support services company that employed the workers.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the gender distribution of the sample compared with the general WA population. There was a higher prevalence of female workers (55.2%) than male workers (44.8%) in the participant sample compared to the general distribution of genders in the WA population [8].

| Gender |

Sample (n) |

Prevalence (%) |

General Population (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 58 | 55.2 | 49.9 |

| Males | 47 | 44.8 | 50.1 |

| Gender distribution (n) and prevalence (%) of the FIFO support service worker sample compared to the prevalence (%) of the Western Australian general population [8] | |||

Table 2 shows the responses to the K10 survey. Participants reported a higher prevalence of higher K10 scores (25.7%) when compared to the general WA population (8.2%) [8].

| Kessler 10 Score | Sample | Prevalence | General Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) (95% CI)† | (%) | |

| Low (10-15) | 54 | 51.4 (51.0-51.9) | 76 |

| Medium (16-21) | 24 | 22.9 (22.3-23.5) | 15.9 |

| High (22-29) | 18 | 17.1(15.9-18.3) | 5.8 |

| Very High (30-50) | 9 | 8.6 (6.4-10.8) | 2.4 |

Table 3 shows the prevalence of coping methods used by participants when they are experiencing periods of difficulty onsite, including loneliness, sadness or stress. In the questionnaire participants were able to select several coping methods. Only 1.9% reported that they would contact a medical professional for help. 1% reported they would contact a mental health support group for help. From the sample, 50.5% said that at times they may keep to themselves during difficult periods on-site. Kendall tau (r2= 0.39) for keeping to themselves indicates a medium positive relationship with higher K10 scores.

| Coping methods |

Sample (n) |

Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Contact family members | 60 | 57.1 |

| Keep to self (not engage with anybody) |

53 |

50.5 |

| Engage in positive thinking | 46 | 43.8 |

| Contact friends – outside of work | 35 | 33.3 |

| Speak to a work colleague | 27 | 25.7 |

| Engage in meditation or relaxation techniques | 19 | 18.1 |

| Write down thoughts in a journal or diary | 7 | 6.7 |

| Speak with supervisor or manager | 4 | 3.8 |

| Contact the Employee Assistance Program | 3 | 2.8 |

| Speak to a medical professional | 2 | 1.9 |

| Contact a public support group | 1 | 1 |

| Prevalence (%) of coping methods used by FIFO support service workers, during difficult times at their workplace | ||

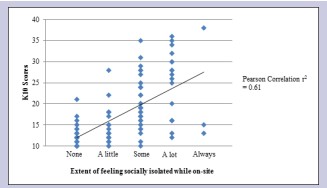

Figure 1: Scatter plot showing the relationship between the extent that FIFO support service workers, n=105, felt socially isolated while at their workplace and K10 scores with supporting Pearson Correlation (r2=0.61)

Table 4 shows the prevalence of workplace bullying with more than half the participants (52.4%) reporting they had been bullied or harassed in their workplace.

| Subjected to workplace bullying or harassment |

Sample (n) |

Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No | 50 | 47.6 |

| YES | 55 | 52.4 |

| Prevalence (%) of FIFO support service worker sample, n=105, reporting being subjected to workplace bullying or harassment in the workplace | ||

DISSCUSSION

No published studies that specifically examined the mental wellbeing of support service FIFO workers could be identified and therefore, this body of work appears to be the first to cover this particular occupational cohort specifically using the K10 scale. The data presented in Table 2 support recent findings of a Parliamentary enquiry in WA that indicates FIFO workers experience higher levels of psychological distress when compared to the general population [2].

It has been shown that a key intervention these remote sites can implement to improve mental health is the provision of good infrastructure for people to engage and socialize and develop a bond and a feeling of belonging, yet they also need to be able to access privacy if desired [4]. The village in question has several free to access high quality gymnasiums and recreational facilities open at all hours where health, fitness and wellbeing classes are regularly organised. All workers have individual accommodation to provide a sense of privacy.

Of concern are the findings presented in Table 3 that only 1.9% of participants were willing to speak to a medical professional about their mental health issues. This appears to be a general industry trend [3]. An explanation for this, and for a general lack of mental health reporting, is that their employment relies on their “fitness for work”, as determined by the specific site medical requirements. A classification that they are unfit, whether for physical or mental reasons would mean they are not permitted to be present on-site to continue their usual work, and would be required to make use of sick leave, and if that runs out, annual or unpaid leave. A key motive for being a FIFO worker is for the associated financial benefits, which usually become tied in with higher standards of living, and property investment. Being locked into a mortgage requiring regular payments builds a reliance on steady income, which leads to a FIFO related condition known as the “golden handcuffs” [2]. For many workers the fear of being removed from site and suffering severe financial distress motivates them not to report health issues. Losing their employment is likely to lead to additional mental health stressors.

Surprisingly only 1% of participants were willing to contact a public support group such a Lifeline or Beyond Blue as a coping method. These services are well advertised and have no connection to employers or medical professionals who could threaten the worker’s employment status, yet workers were not willing to make contact when needing support. The company has a contracted Employee Assistance Program (EAP) that provides confidential counselling free of charge to workers and immediate family. Contact information for the EAP is provided during the site induction and displayed on a discrete poster in the worker’s accommodation. Only 2.8% of survey participants said they would contact the EAP as a coping method. As identified in previous studies [3], there appears to be a stigma attached to contacting support groups due to a fear that doing so may deem the worker to be unfit for work. This is a matter that merits further investigation.

Where 50.5% of participants indicated they kept to themselves as a coping method, there was a medium positive relationship (r2= 0.39) with higher K10 scores. This coincides with Figure 1, where the extent of feeling socially isolated was strongly correlated to high K10 scores (r2= 0.61). These findings are supported by findings in a Queensland FIFO environment [3]. This parallels current literature which identifies that not engaging in a social environment with peers and leading an inactive lifestyle was also linked to a perception of poor overall wellbeing [9,10].

Workplace bullying or harassment appears to be quite prevalent among this cohort (>50%) and there is also a moderate positive correlation between bullying and high K10 scores (r2= 0.31). A recent study has confirmed that workplace bullying is directly related to poor mental health [11]. The report of the Education and Health Standing Committee has recommended changes to legislation to hold responsible those individuals who are found guilty of bullying [2]. The company has specific policies on fair treatment, discrimination and harassment and provides basic training to all workers. More could be done to develop the workers’ understanding of coping methods and building resilience for working in remote regions. There would be benefits to providing additional training to managers and supervisors on preventing bullying and harassment and for how to support the mental health of their workers.

A number of limitations were identified that affected this study;

1. Participants self-selected to participate in the survey and it is therefore likely that people that were concerned about their mental health may have been over sampled thus leading to an over-estimation of the extent of the problem.

2. Media coverage of suicide in the industry immediately prior to the study would also have sensitised the population, particularly since one of their colleagues had suicided recently.

3. The nature of FIFO rosters is such that the workers are constantly rotating through their periods on-site and off-site which impacted on recruitment as many workers missed briefing sessions and assumed the email was “junk mail” and so they did not respond.

CONCLUSION

Support service workers are a key component of any project in the remote WA resources industry and these workers are often overlooked when evaluating FIFO workers, yet they experience the same challenges associated with FIFO work. This survey determined that these workers report higher levels of psychological stress when compared to the general population. Feeling isolated on-site significantly increased likelihood of experiencing higher levels of psychological distress and workers are reluctant to report mental health issues. It also appears as if workplace bullying and harassment is a significant issue among this cohort.

The findings of this study should be validated by conducting similar surveys among cohorts of support service workers in different environments, using random sampling methods to eliminate self-selection bias and in workplaces with no history of recent suicide among the cohort. An area of interest for further investigation would be to explore reasons for the apparent stigma attached to reporting personal mental health issues. The extent of bullying and harassment among this work cohort also requires further investigation.

Employers need to develop robust and evidence based interventions to ensure they fulfil their duty of care obligations to provide a safe work environment from a mental health perspective and to protect their workers from bullying, harassment and harm. Employee relations can be improved by encouraging open discussion about social isolation, “golden handcuff” concerns, job satisfaction and workplace bullying. Company policy should incorporate financial advice for workers, training programs to build resilience of workers in remote regions, and team-building strategies to cultivate a sense of community and reduce the feeling of social isolation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the support service company and their employees for participating in the questionnaire and making the project possible.

DISCLOSURE

There was no financial interest or conflict of interest in producing this report.

About the Corresponding Author

Matthew Sellenger

Summary of background:

Masters of Occupational Health and Safety

Bachelor of Science: Anatomical Science (Major in Anatomy & Human Biology)

Permanent e-mail address: mr.sellenger@gmail.com