Cardiotoxicity after Thoracic Radiotherapy: Multimodality Imaging Strategies for Early Detection and Surveillance

- 1. Department of Cardiology, Hitit University Erol Olçok Education and Research Hospital, Turkey

- 2. Department of Cardiology, Faculty of Medicine, Hitit University, Turkey

Abstract

Thoracic radiotherapy remains an essential component of curative treatment for multiple malignancies, yet cardiac exposure during treatment continues to generate clinically relevant long-term toxicity. Radiation-induced heart disease represents a broad continuum of coronary, myocardial, valvular, pericardial, microvascular, autonomic, and conduction system abnormalities that may evolve silently for years before becoming symptomatic. Early injury is typically driven by endothelial dysfunction, microvascular ischemia, and progressive fibrosis affecting myocardial and pericardial tissues, while late complications include left anterior descending artery–dominant coronary disease, restrictive or dilated cardiomyopathy, fibrotic valvulopathy, constrictive pericarditis, and clinically significant arrhythmias. Because these processes often begin subclinically, early detection has become central to modern cardio-oncology. Multimodality cardiovascular imaging provides a complementary and increasingly individualized approach to surveillance. Transthoracic echocardiography with global longitudinal strain allows early identification of functional decline before reductions in ejection fraction occur. Cardiac magnetic resonance offers superior quantification of ventricular performance and enables detailed tissue characterization through late gadolinium enhancement, T1/T2 mapping, and extracellular volume assessment. Coronary CT angiography improves anatomical evaluation of proximal and ostial coronary lesions typical of radiation-associated disease, while nuclear imaging techniques reveal inflammation and microvascular dysfunction at stages when structural injury is not yet apparent. Integrating imaging f indings with radiotherapy dosimetry, systemic therapy history, patient-specific cardiovascular risk, and evolving guideline recommendations enables risk adapted, longitudinal follow-up. This narrative review synthesizes current evidence on the pathophysiology, clinical spectrum, and diagnostic performance of multimodality imaging after thoracic radiotherapy, and proposes a practical surveillance framework aimed at detecting subclinical cardiac injury early enough to influence long-term outcomes in cancer survivors.

Keywords

• Radiation-induced heart disease

• Cardio-oncology

• Multimodality imaging

• Thoracic radiotherapy

• Cardiotoxicity surveillance

Citation

B?RGÜN A, KALÇIK M, ÇEL?K MC, YET?M M, BEKAR L, et al. (2026) Cardiotoxicity after Thoracic Radiotherapy: Multimodality Imaging Strategies for Early Detection and Surveillance. J Radiol Radiat Ther 14(1): 1117.

INTRODUCTION

Thoracic radiotherapy (RT) remains a fundamental component of curative treatment for breast cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, lung cancer, and esophageal cancer, with millions of patients worldwide receiving chest directed irradiation annually [1]. Over recent decades, substantial advances in RT planning, cardiac contouring, and dose-sparing techniques have markedly reduced mean heart doses compared with historical regimens. Nevertheless, epidemiologic data consistently indicate that clinically relevant cardiac injury persists even with contemporary protocols, and that thoracic RT continues to contribute to long-term cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in cancer survivors [2].

Radiation-induced heart disease (RIHD) represents a broad constellation of structural and functional cardiac abnormalities attributable to ionizing radiation. These injuries encompass pericardial inflammation, microvascular dysfunction, myocardial fibrosis, valvular thickening and calcification, coronary artery disease particularly involving the left anterior descending artery and a spectrum of arrhythmias and conduction disturbances [3]. Conceptually, it is useful to distinguish between acute injury, which may manifest within weeks to months as pericarditis or transient arrhythmias, and chronic injury, which typically evolves over years to decades and reflects progressive microvascular ischemia, fibrosis, and accelerated atherosclerosis [4]. The latency of these processes underscores the insidious nature of RIHD and the need for surveillance strategies that extend far beyond the completion of cancer therapy.

Early detection of subclinical cardiac injury is particular importance because many radiation induced abnormalities are initially silent, cumulative, and potentially irreversible once overt fibrosis or fixed coronary obstruction develops. Observational cohorts of breast cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma survivors demonstrate that measurable cardiovascular risk persists lifelong and may manifest decades after treatment, often at an age when patients would otherwise be expected to enjoy good functional status [5]. Identifying early changes such as impaired global longitudinal strain, rising biomarkers, or subtle tissue alterations on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging provides an opportunity to initiate preventive cardiology interventions, optimize risk factor modification, and guide timely referral to cardio oncology services before the onset of symptomatic disease. Within this landscape, multimodality cardiovascular imaging has emerged as a central pillar of contemporary cardio-oncology. Each imaging technique contributes unique diagnostic value: transthoracic echocardiography enables first-line assessment and serial monitoring; strain imaging detects subclinical systolic impairment; cardiac magnetic resonance provides unparalleled tissue characterization; coronary CT angiography characterizes plaque morphology and coronary stenosis; and nuclear imaging refines evaluation of perfusion and inflammatory activity. Integrating these tools within a risk-adapted framework considering radiation dose metrics, chemotherapy exposures, patient age, and baseline cardiovascular risk has become essential for accurate phenotyping of RIHD and for tailoring surveillance intervals. The aim of this narrative review is to synthesize current evidence on the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnostic performance of multimodality imaging in detecting radiation-associated cardiotoxicity after thoracic RT. In doing so, we outline key dose–response principles, describe the temporal progression of cardiac injury, summarize the strengths and limitations of imaging modalities across the disease continuum, and propose a pragmatic surveillance strategy grounded in contemporary cardio-oncology guidelines. Our goal is to provide clinicians with an evidence informed, imaging centered approach to the early recognition and management of RIHD in the modern era of cancer survivorship.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF RADIATION-INDUCED HEART DISEASE (RIHD)

Radiation dose Parameters

Cardiac radiation exposure is neither uniform nor

biologically equivalent across myocardial, coronary, valvular, and pericardial tissues. The risk of clinically meaningful RIHD is governed not only by mean heart dose (MHD) but also by regional dose distribution, fractionation, dose rate, and the sensitivity of individual cardiac substructures. Historically, MHD served as the primary surrogate for late cardiac risk, with Darby et al., showing a linear increase in major coronary events of 7.4% per 1 Gy increase in MHD after breast RT [1]. Although this landmark dose–response relationship remains influential, contemporary analyses reveal that MHD alone often masks the heterogeneous internal anatomy of the heart, in which small but critical structures may receive disproportionately high doses.

One such structure is the left anterior descending (LAD) artery, which frequently lies within the tangential radiation field in left-sided breast cancer. Even when whole-heart doses are low, LAD hotspots may reach 20–40 Gy, creating a focal atherosclerotic nidus not captured by MHD [6]. LAD maximum dose (LAD_max) and mean dose (LAD_mean) have each been independently associated with subsequent stenosis, ostial calcification, and perfusion defects, suggesting that coronary-specific dosimetry provides superior predictive value compared to global metrics. In mediastinal radiation particularly for Hodgkin lymphoma doses to the proximal coronary locations, including the left main and RCA ostium, may also be clinically relevant due to anterior mediastinal beam arrangements [7,8].

Beyond coronary exposures, dose–volume histograms (DVHs)incorporatingV5,V20,andV30havebecomeintegral for understanding differential injury patterns. V5 reflects low-dose scatter, associated with long-term microvascular dysfunction and subtle diastolic abnormalities. V20–V30 capture higher-dose regions associated with pericardial fibrosis, myocardial remodeling, and clinically overt cardiomyopathy [7]. These DVH metrics help distinguish global low-dose exposure (breast RT) from patchy high- dose exposure (lymphoma RT), each producing distinct biological trajectories.

Substructure-based contouring now recommended in multiple radiation oncology guidelines has expanded risk prediction by enabling dose quantification to the left ventricle, right ventricle, atria, pericardium, AV nodal region, and cardiac valves. Pericardial V20, mitral valve Dmean, and right atrial exposure, for example, have each been linked to downstream pericardial constriction, valvular calcification, and arrhythmia risk respectively. Modern RT software and atlas-based segmentation have shown that even small increases in valvular Dmean can translate into progressive leaflet thickening over decades, particularly for the aortic valve.

Emerging data highlight that fractionation schemes and dose rate also modify biological injury. Hypofractionated RT, while safe in most breast cancer cohorts, may produce higher instantaneous endothelial stress, whereas proton therapy reduces integral dose but can generate sharp distal dose gradients that occasionally affect substructures unpredictably [9]. Similarly, the adoption of deep inspiration breath hold (DIBH) enlarges the thoracic cavity, displacing the heart inferiorly and posteriorly, thereby reducing both MHD and LAD_mean by 30–60% in many left-sided treatments.

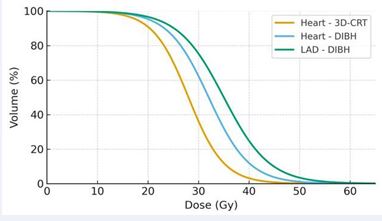

Despite significant progress, modern techniques do not eliminate risk. Even with contemporary conformal therapy, MHD of 1–3 Gy and LAD_mean of 5–10 Gy are common in left-sided breast RT, while mediastinal lymphoma therapy may produce highly heterogeneous patterns depending on beam arrangement. Thus, the integration of whole- heart metrics (MHD), coronary-specific dosimetry (LAD_ mean, LAD_max), and substructure dose parameters (pericardium, valves, conduction system) yields the most accurate framework for predicting long-term RIHD. An illustrative comparison of whole-heart and LAD dose– volume histograms demonstrating the dosimetric impact of deep inspiration breath-hold versus conventional techniques is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Comparative dose–volume histograms (DVH) for the whole heart and the left anterior descending artery (LAD) demonstrating the dosimetric impact of two radiotherapy techniques in left-sided breast irradiation. The yellow curve represents the whole-heart DVH obtained with three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT), showing higher dose exposure across the cardiac volume. The blue and green curves represent deep inspiration breath- hold (DIBH) plans for the whole heart and the LAD, respectively, illustrating substantial reductions in the proportion of heart volume receiving low– intermediate doses and marked decreases in LAD dose. This pattern highlights how DIBH displaces the heart away from the tangential fields and thereby reduces radiation exposure to both the whole heart and LAD.

Cellular and Tissue Injury Mechanisms

Radiation-induced heart disease (RIHD) reflects a cascade of molecular, microvascular, and structural alterations that evolve over years. The earliest injury

occurs at the level of the vascular endothelium, where ionizing radiation promotes DNA damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and chronic reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, impairing nitric oxide signaling and triggering pro-inflammatory adhesion molecule expression [10]. These changes lead to microvascular rarefaction, impaired coronary flow reserve, and diffuse ischemia that may be clinically silent for years.

Ionizing radiation also activates TGF-β–mediated profibrotic pathways, stimulating fibroblast proliferation and differentiation into myofibroblasts. The result is progressive interstitial and replacement fibrosis, a hallmark of chronic RIHD and a key substrate for diastolic dysfunction, conduction abnormalities, and restrictive physiology [11]. This fibrotic process occurs in both the myocardium and pericardium, where acute inflammatory changes may transition into thickening, adhesions, and eventually constrictive pericarditis.

Coronary vasculature demonstrates a unique form of accelerated atherosclerosis, characterized by fibrocalcific and often ostial lesions, most prominently affecting the left anterior descending artery (LAD). This pattern aligns closely with localized high-dose exposure [6], and differs biologically from conventional atherosclerosis by involving greater inflammatory activity and more rapid luminal narrowing.

Valvular structures also display radiation sensitivity. Exposure induces valvular interstitial cell transformation toward an osteogenic phenotype, resulting in leaflet thickening, fibrosis, and progressive calcification particularly affecting the aortic and mitral valves [12]. Over decades, this process produces clinically significant stenosis or regurgitation.

Radiation effects on the conduction system including the sinoatrial node, atrioventricular node, and His– Purkinje pathways are mediated by microvascular injury and fibrosis, which may present as bradyarrhythmias or conduction block even in the absence of overt cardiomyopathy [5]. Taken together, RIHD represents a multifaceted and time-dependent interplay of endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, fibrosis, and accelerated vascular aging.

Clinical Syndromes and Timeline

Radiation-induced cardiovascular injury spans a wide temporal spectrum, with early, intermediate, and late manifestations.

Early phase (weeks to months)

Early RIHD is uncommon but clinically relevant.

Acute pericarditis remains the most recognized early presentation, often occurring within the first three months after mediastinal RT. Transient arrhythmias, minor troponin elevations, or myocarditis-like inflammatory changes may also appear but are less frequent [5]. These early findings often resolve but may seed long-term structural changes.

Intermediate phase (1–5 years)

The intermediate period is characterized by subclinical abnormalities detectable primarily through imaging and functional assessment rather than symptoms. Persistent endothelial dysfunction and microvascular impairment manifest as reduced myocardial perfusion reserve, early diastolic dysfunction, or declines in global longitudinal strain (GLS). Cohort studies incorporating advanced echocardiographic and biomarker surveillance demonstrate that survivors may develop subtle systolic impairment long before LVEF declines [10]. During this phase, pericardial thickening or small effusions may develop, and mild valvular thickening can begin.

Late phase (>5–10 years and lifelong)

The late phase accounts for most clinically significant RIHD. Coronary artery disease particularly involving the LAD is the predominant manifestation, often presenting as exertional angina, atypical chest pain, or myocardial infarction decades after treatment [6,9]. Progressive valvular heart disease, especially aortic stenosis and mitral regurgitation, emerges over 10–20 years and may require surgical or transcatheter intervention (12).

Chronic restrictive or dilated cardiomyopathy may occur due to diffuse myocardial fibrosis, leading to heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Late pericardial complications, including constrictive pericarditis, can present with right-sided heart failure, ascites, or peripheral edema. Conduction system disease manifesting as sick sinus syndrome or varying degrees of atrioventricular block may appear many years after irradiation secondary to progressive fibrosis [5].

Survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma and left-sided breast cancer are particularly vulnerable, with risk persisting lifelong, often extending into the fifth and sixth decades of life despite modern dose-sparing radiotherapy [7,9]. This long latency underscores the need for risk-adapted, imaging-based surveillance strategies.

Clinical Spectrum of Cardiotoxicity After Thoracic RT

Coronary Artery Disease (LAD-dominant)

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most extensively characterized and clinically consequential late manifestation of radiation-induced heart disease. Radiation accelerates atherosclerosis through endothelial dysfunction, chronic inflammation, and fibrocalcific plaque formation—changes that differ from age-related atherosclerosis by their earlier onset and anatomic predilection [1,9]. Among coronary vessels, the left anterior descending (LAD) artery is disproportionately affected due to its anterior position within the radiation field, making it a consistent dosimetric hotspot during left- sided breast and mediastinal radiotherapy [6].

Large epidemiological cohorts show a linear dose– response relationship between cardiac exposure and major coronary events, with ischemic risk increasing by approximately 7.4% per Gy of mean heart dose (MHD) [1]. However, contemporary dosimetric analyses indicate that global metrics underestimate risk, and that coronary substructure–specific dose parameters, particularly LAD_ mean and LAD_max, better predict long-term events [6,7]. This shift toward coronary-focused dosimetry reflects the recognition that even when MHD is low, localized high- dose exposure within the LAD can drive early ischemic injury.

Emerging prospective imaging studies support this mechanistic understanding. In a 2023 cohort of left-sided breast cancer survivors, higher LAD-adjacent subvolume doses were significantly associated with new SPECT- detected myocardial perfusion defects at 6–12 months after radiotherapy, even in patients with minimal traditional risk factors [13]. This reinforces the concept that radiation- induced CAD begins as subclinical microvascular ischemia long before overt stenosis develops.

Clinically, radiation-associated CAD typically presents 10–20 years after treatment, but onset may be earlier in individuals receiving high-dose mediastinal irradiation. Patients may exhibit exertional angina, dyspnea, or atypical symptoms; a sizable proportion develop silent ischemia detectable only through stress imaging or coronary CT angiography. Characteristic findings include proximal LAD stenosis, left main ostial involvement, and multivessel fibrocalcific disease, which can complicate both percutaneous and surgical revascularization [6,9].

Together, these data highlight that the coronary consequences of thoracic radiotherapy are both dose- dependent and region specific, underscoring the need for precise LAD sparing in RT planning and long-term coronary surveillance in all thoracic RT survivors.

Cardiomyopathy

Myocardial injury after thoracic radiotherapy develops through a slow and progressive cascade driven by microvascular damage, chronic inflammation, and fibrosis. Endothelial dysfunction and impaired coronary flow reserve appear early, setting the stage for diffuse interstitial fibrosis that predominantly affects ventricular compliance and relaxation rather than early systolic performance [10]. Diastolic dysfunction, therefore, represents the most frequent and earliest measurable form of radiation associated myocardial impairment, even in patients without significant coronary artery disease [9].

In the intermediate phase after RT, subtle abnormalities in myocardial deformation especially impaired global longitudinal strain (GLS) may emerge despite normal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) [10]. These subclinical changes reflect diffuse myocardial remodeling and are strongly associated with cumulative radiation dose to left ventricular substructures, including the anterior and septal myocardial segments commonly exposed during mediastinal or left-sided breast radiotherapy [6]. Importantly, fibrosis resulting from this process is often irreversible, highlighting the clinical importance of detecting early functional changes before overt cardiomyopathy develops [1].

Over the long term, survivors may progress to either restrictive or dilated cardiomyopathy depending on the balance between microvascular ischemia, fibrotic burden, and concomitant risk factors. Late manifestations may arise 10–30 years after exposure and are frequently accompanied by pericardial thickening, valvular disease, or conduction abnormalities that compound ventricular dysfunction [9]. Left-sided breast cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma survivors remain at the highest risk due to historically higher mediastinal and LAD adjacent myocardial doses [6].

Given the predominantly subclinical and diastolic nature of early injury, contemporary cardio-oncology guidelines emphasize the role of GLS based echocardiography, serum biomarkers, and cardiac MRI T1/T2 mapping for early detection and longitudinal surveillance in thoracic RT survivors [14]. These modalities can identify microvascular and fibrotic changes long before LVEF declines, enabling a window for preventive strategies such as aggressive risk- factor modification, cardioprotective pharmacotherapy, and tailored imaging follow-up [14].

Valvular Heart Disease

Radiation-induced valvular heart disease (VHD) represents a distinct and increasingly recognized late manifestation of thoracic radiotherapy. Unlike age- related degenerative valve disease, radiation-associated valvulopathy demonstrates fibrocalcific thickening, reduced leaflet mobility, and a strong predilection for the aortic and mitral valves, which lie closest to the central mediastinal radiation field [12]. Histopathologically, ionizing radiation induces valvular interstitial cell transformation toward an osteogenic phenotype, resulting in progressive leaflet fibrosis and calcification over decades [12].

The onset of radiation-associated VHD is typically delayed. Mild thickening and early regurgitant lesions may appear within 5–10 years after treatment, but clinically significant stenosis or mixed valvular dysfunction generally manifests ≥15–20 years post RT. Survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma treated with mantle-field RT and left-sided breast cancer patients represent the highest-risk groups due to historically higher anterior mediastinal doses [9].

Recent population-level data confirm that thoracic RT increases the long-term risk of aortic stenosis, mitral regurgitation, and tricuspid regurgitation, with hazard ratios ranging from 2.3 to 7.0 depending on valve type and radiation dose [15]. Aortic stenosis tends to develop earlier and progress more aggressively than in non-irradiated patients, likely due to combined valvular and aortomitral curtain fibrosis. Mitral regurgitation is often functional in the early phase, related to subclinical LV remodeling, and later becomes structural as leaflet calcification progresses [12].

Radiation-associated VHD frequently coexists with coronary disease, pericardial fibrosis, and restrictive cardiomyopathy, creating a unique clinical profile that complicates both diagnosis and intervention [9]. Surgical aortic or mitral valve replacement carries increased perioperative risk due to mediastinal fibrosis, impaired wound healing, and coexistent CAD. As a result, transcatheter valve interventions (TAVR, TEER) have emerged as attractive alternatives, showing favorable outcomes in irradiated survivors [15].

Lifelong surveillance is recommended, especially for patients treated before age 30 or with high mediastinal doses. Echocardiography remains the cornerstone of detection, while CT provides superior evaluation of valvular calcification and aortomitral complex anatomy features especially relevant for planning transcatheter therapies [12].

Pericardial Disease (Acute vs Chronic Constrictive)

Pericardial involvement is one of the earliest and most frequent manifestations of radiation-induced heart disease, with a spectrum ranging from acute pericarditis to chronic effusion, fibrotic thickening, and late constrictive pericarditis [16,17]. The underlying mechanism combines microvascular injury, increased capillary permeability, and chronic inflammation, ultimately leading to fibrotic remodeling of the pericardial layers [16,18].

Acute Pericarditis

Acute radiation-induced pericarditis usually occurs during thoracic radiotherapy or within weeks to a few months after treatment. Patients may present with pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea, tachycardia, pericardial friction rub, and nonspecific ST–T changes on ECG; echocardiography often reveals a small pericardial effusion or isolated pericardial thickening [16,17]. In most cases, the clinical course is self-limited and responds well to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and colchicine, following general pericarditis management principles [19]. Interruption of radiotherapy is rarely required, but close monitoring is recommended in patients with significant symptoms or hemodynamic instability [16].

Chronic Pericardial Effusion and Fibrotic Remodeling

Chronic pericardial effusion is a common intermediate- term manifestation in thoracic radiation survivors. Contemporary cardio-oncology series report pericardial effusion in up to 10–50% of patients, particularly in those with mediastinal irradiation for lung cancer, lymphoma, or breast cancer [17,18]. Most effusions are small and asymptomatic, often detected incidentally on surveillance echocardiography; however, large or rapidly accumulating effusions may lead to cardiac tamponade and require urgent drainage [17,19]. Persistent low-grade inflammation and impaired lymphatic drainage promote pericardial thickening and fibrosis, which can gradually compromise ventricular filling even in the absence of overt tamponade [18].

Constrictive Pericarditis

Radiation-induced constrictive pericarditis is a late, relatively rare but clinically severe complication that typically appears 5–20 years after mediastinal irradiation [16,17]. Patients present with right-sided heart failure elevated jugular venous pressure, peripheral edema, hepatomegaly, ascites and characteristic findings such as Kussmaul’s sign and prominent y descent. Cross-sectional imaging often shows a markedly thickened and sometimes calcified pericardium, and invasive hemodynamics reveal dissociation of intrathoracic and intracardiac pressures with ventricular interdependence [16,18].

Pericardiectomy remains the only definitive treatment for advanced constrictive physiology. However, outcomes are significantly worse in radiation-associated constriction than in other etiologies: in a large contemporary series, pericardiectomy after mediastinal irradiation was associated with an operative mortality around 10% and 1-, 5-, and 10-year survival rates of approximately 74%,

53%, and 32%, respectively [20]. These data underscore the importance of early recognition and careful patient selection, as well as the need for a multidisciplinary discussion in high-risk thoracic RT survivors [16,20].

Diagnosis, Surveillance, and Management

Diagnosis, surveillance, and management of radiation- associated pericardial disease begin with transthoracic echocardiography, which remains the first line modality for detecting pericardial effusion, estimating hemodynamic impact, and identifying indirect signs of constriction [19]. When further anatomical detail is required, advanced imaging with CT or cardiac MRI provides superior characterization of pericardial thickness, calcification, and associated myocardial or valvular involvement features that carry particular relevance in patients with a previously irradiated mediastinum [16,18]. Within contemporary cardio-oncology frameworks, this imaging strategy supports a clinical approach centered on baseline and periodic echocardiography for high-risk thoracic RT survivors, rapid evaluation of any new dyspnea, edema, or unexplained right-sided heart failure, early drainage for large symptomatic effusions or tamponade, and timely referral to experienced centers for consideration of pericardiectomy when constrictive pericarditis is established [17-20].

Conduction System Disease (AV Block / Sinus Node Dysfunction / Arrhythmias)

Radiation-induced injury to the cardiac conduction system is less frequent than coronary, valvular, or pericardial involvement, yet it constitutes a clinically relevant and sometimes under-recognized manifestation of RIHD. Contemporary cardio-oncology data indicate that conduction abnormalities including sinus node dysfunction, atrioventricular (AV) block, bundle branch block, and ventricular arrhythmias occur in approximately 4–5% of long-term thoracic radiotherapy survivors [21].

Pathophysiology

Ionizing radiation induces microvascular endothelial damage, localized ischemia, chronic inflammation, and progressive fibrosis within nodal and His–Purkinje tissues, leading to delayed conduction and impaired automaticity [22]. Experimental models and human myocardial tissue analyses have shown that radiation can also alter ion- channel expression and connexin profiles specifically Na_v1.5 and connexin-43 thereby promoting conduction slowing and creating an arrhythmogenic substrate independently of structural fibrosis [23].

Clinical Presentation and Timing

Conduction system disease typically presents years to decades after mediastinal irradiation. Clinical manifestations include sinus bradycardia, chronotropic incompetence, first- to third-degree AV block, new-onset bundle branch block, or unexplained syncope [21]. In certain cases especially following high-dose mediastinal RT or combined chemo-radiation conduction abnormalities may emerge earlier, within the first 1–5 years [22]. These rhythm disturbances often coexist with other components of RIHD, such as myocardial fibrosis or pericardial thickening, complicating diagnosis and management.

Management and Clinical Implications

Given the potential for sudden high-grade AV block or symptomatic bradyarrhythmias, lifelong ECG surveillance is recommended for thoracic RT survivors, particularly those treated for lymphoma or receiving anterior mediastinal fields [21). Pacemaker implantation follows standard clinical indications; however, device implantation may be technically challenging due to venous stenosis, fibrosis, or altered thoracic anatomy after prior radiation [22].

Ventricular arrhythmias related to fibrosis or conduction heterogeneity may require antiarrhythmic therapy, catheter ablation, or implantable cardioverter- defibrillator placement. Novel therapies such as stereotactic arrhythmia radioablation (STAR) have shown promise in refractory ventricular tachycardia, although their role specifically in radiation-injured myocardium requires further study [23].

Autonomic Dysfunction

Autonomic dysfunction is an emerging feature of thoracic RT–related cardiotoxicity, characterized by reduced heart-rate variability, impaired parasympathetic activity, and sympathetic predominance [24,25]. Radiation may injure intramyocardial autonomic fibers or their microvascular supply, leading to inflammation, oxidative stress, and disruption of autonomic signaling pathways [26]. Prospective data demonstrate measurable declines in HRV indices and deceleration capacity shortly after RT changes that can occur even without concurrent chemotherapy and often precede structural myocardial abnormalities [24,25]. Clinically, autonomic imbalance may present with resting tachycardia, impaired heart- rate recovery, orthostatic symptoms, exercise intolerance, or increased susceptibility to arrhythmias [24]. Because these alterations appear early and may amplify other components of RIHD, incorporating periodic HRV assessment or simple autonomic testing into follow-up may help identify high-risk patients, although specific therapeutic strategies remain limited [26].

Multimodality Imaging: Principles and Diagnostic Performance

Transthoracic Echocardiography (TTE)

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is the first-line imaging tool for evaluation and long-term surveillance of patients exposed to thoracic radiotherapy, owing to its availability, cost-effectiveness, and suitability for serial follow-up [27]. Beyond conventional measures such as chamber size and ejection fraction, TTE provides detailed functional assessment and early detection of radiation- associated cardiac alterations.

A major strength of TTE in this setting is strain imaging, particularly global longitudinal strain (GLS), which identifies subclinical LV dysfunction before any decline in LVEF occurs. This is crucial because myocardial injury in radiation-induced heart disease often begins with subtle microvascular and fibrotic changes progressing silently over years [28]. GLS is therefore recommended as part of routine surveillance for early cardiotoxicity.

TTE is also central in evaluating diastolic function, which is frequently impaired after RT due to diffuse myocardial fibrosis and stiffening. Doppler and tissue Doppler indices help reveal abnormalities in relaxation and filling pressures even when systolic performance remains preserved [27].

Structural changes related to radiation including valvular thickening, early calcification, or pericardial effusion/thickening are readily detected by TTE, making it an essential tool for monitoring progressive valvulopathy and pericardial involvement [29]. However, limitations exist: acoustic windows may be compromised by chest wall fibrosis or prior surgery, and TTE may underestimate subtle myocardial fibrosis or small pericardial thickness increases, necessitating complementary imaging such as CMR or CT when diagnostic uncertainty persists [28].

Overall, TTE remains the cornerstone modality for surveillance in thoracic RT survivors, especially when combined with advanced deformation imaging to detect early, potentially reversible abnormalities.

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CMR)

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) is considered the gold standard for quantifying ventricular volumes, systolic function, and myocardial tissue characteristics in cardio-oncology, and is particularly valuable when echocardiographic windows are suboptimal or when a precise LVEF assessment is required [30,31]. Multiparametric CMR combines cine imaging, tissue characterization, perfusion, and strain, providing a comprehensive evaluation of radiation-induced heart disease.

A central strength of CMR in thoracic RT survivors is late gadolinium enhancement (LGE), which detects replacement fibrosis. In patients previously treated with chest radiotherapy, LGE often appears in non ischemic subepicardial or mid wall patterns within the LV or septum, reflecting focal fibrotic injury related to prior dose distribution [30,32]. These LGE abnormalities represent irreversible scarring and have been associated with adverse remodeling and worse outcomes in cancer survivors [31].

Beyond focal fibrosis, T1 and T2 mapping techniques enable quantification of diffuse interstitial fibrosis and myocardial edema, changes that are frequently invisible on LGE alone [30,31]. Native T1 and extracellular volume (ECV) mapping can detect early myocardial injury and subtle interstitial expansion; in breast cancer and other cohorts, elevated T1/ECV has been linked with subsequent cancer therapy–related cardiac dysfunction and may serve as an early biomarker of cardiotoxicity [32,33]. In selected patients, stress CMR with quantitative perfusion mapping can also unmask microvascular dysfunction, which is highly relevant in radiation-induced microvascular disease even when epicardial coronaries are angiographically normal [32].

Finally, feature-tracking CMR strain analysis allows measurement of global and regional myocardial deformation from standard cine images. CMR-derived GLS and circumferential strain can reveal subclinical LV dysfunction in cancer survivors with preserved LVEF and may complement echocardiographic strain when image quality is limited [31,33]. Taken together, CMR provides a uniquely powerful integration of structure, function, fibrosis, perfusion, and deformation in patients exposed to thoracic radiotherapy.

Coronary CT Angiography (CCTA)

Coronary CT angiography (CCTA) has become a key modality in evaluating radiation-associated coronary artery disease (RICAD), particularly because of its high spatial resolution and ability to characterize plaque morphology. CCTA accurately detects coronary stenosis, identifies non-obstructive and obstructive plaque, and provides detailed assessment of lesion composition, including fibrocalcific and mixed plaques that are typical in radiation-exposed vessels [34].

Thoracic radiotherapy disproportionately affects the left anterior descending (LAD) artery, given its anatomic proximity to left-sided breast and mediastinal fields. CCTA demonstrates high sensitivity for LAD involvement, identifying even subtle proximal or ostial lesions that may be missed on functional testing [35]. In long-term survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma and breast cancer, CCTA-derived coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring is useful for stratifying risk and predicting major adverse cardiovascular events, especially when asymptomatic [36].

CCTA is particularly advantageous in asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients, where stress testing may be non-diagnostic and echocardiography lacks sensitivity for early coronary disease. Quantitative CCTA also enables assessment of luminal narrowing, plaque burden, and adverse plaque features remodeling, spotty calcification, low-attenuation plaque which may be more prevalent in RT-induced disease [34,35].

Radiation-associated plaques often exhibit distinctive features: fibrocalcific composition, ostial or proximal location, and involvement of the left main LAD axis patterns different from typical atherosclerosis and more easily appreciated with CCTA [35,36].

Limitations include the need for iodinated contrast, potential for heart rate dependent motion artifacts, and the additional radiation dose, which requires careful risk benefit consideration in cancer survivors. Nevertheless, with modern low-dose protocols and iterative reconstruction techniques, radiation exposure from contemporary CCTA examinations has been substantially reduced [37].

Nuclear Imaging (SPECT, PET)

Nuclear imaging provides functional information that complements anatomic modalities in the evaluation of radiation-induced heart disease. Early after thoracic radiotherapy, FDG-PET can detect increased myocardial or pericardial FDG uptake in regions receiving higher radiation doses, reflecting an inflammatory–metabolic response that precedes structural remodeling [38]. These focal uptake patterns often appear within the irradiated myocardial volume and may be present even in clinically asymptomatic patients.

In thoracic malignancies, FDG-PET/CT frequently demonstrates localized myocardial or pericardial uptake confined to the radiation field, supporting the concept of radiation-associated myocarditis or microvascular inflammation rather than classic ischemic disease [39]. Hybrid PET/MRI studies extend these findings by showing simultaneous increases in FDG uptake, extracellular volume, and subtle reductions in stroke volume as early as one month after left-sided breast radiotherapy, reinforcing the role of PET in identifying an inflammatory edematous phase of RIHD [40].

Beyond inflammation, PET allows quantitative assessment of myocardial blood flow (MBF) and myocardial flow reserve (MFR), which is particularly valuable in survivors with suspected microvascular dysfunction. In long-term thoracic RT survivors, reduced global and LAD territory MFR has been demonstrated despite normal epicardial coronaries, indicating a radiation-induced microvascular phenotype with vasomotor impairment [41]. MBF and MFR quantification offer mechanistic links between radiation dose, perfusion abnormalities, and subsequent functional decline.

Finally, PET-based flow quantification techniques are supported by robust methodological literature showing high reproducibility and strong prognostic value across cardiovascular populations, making PET a powerful adjunct to CMR and CT when diffuse microvascular disease or early cardiotoxicity is suspected [42]. Compared with CMR and CT, nuclear techniques excel in detecting subtle flow abnormalities and inflammation, although their limitations include radiation exposure and lower spatial resolution (particularly in SPECT). The complementary diagnostic roles, strengths, and limitations of each cardiovascular imaging modality in radiation-induced heart disease are summarized in Table 1.

Surveillance Algorithms and Follow-Up Strategies

International Guideline Comparison

Follow-up strategies for radiation-induced heart disease (RIHD) vary across international societies, yet all converge on a risk stratified approach combining radiation dosimetry, cancer therapy exposures, patient specific cardiovascular (CV) risk, and time from treatment. Among available documents, the 2022 ESC Cardio-Oncology Guidelines provide the most detailed and algorithmic framework, whereas ASCO, NCCN, and earlier ESC position statements offer complementary principles focusing on survivorship and multimodality surveillance [43–49]. Foundational evidence for radiation-associated risk estimation is drawn largely from observational cohorts and large cardio-oncology reviews [35].

ESC Cardio-Oncology 2022

ESC 2022 adopts a structured high, moderate, and low-risk model for long-term follow-up of thoracic RT survivors, integrating detailed dosimetry and treatment history into a single framework. The central determinant is the mean heart dose (MHD): patients with MHD >15 Gy or with substantial substructure exposure such as proximal LAD doses exceeding 20 Gy fall into the high-risk category, whereas those with MHD between 5 and 15 Gy are considered moderate risk, and individuals exposed to

<5 Gy are classified as low risk. This baseline classification is then modified by additional factors that meaningfully amplify susceptibility to radiation-related cardiovascular disease, including concomitant anthracycline therapy (which adds independent cardiotoxicity and synergistic injury), pre-existing cardiovascular disease, multiple conventional CV risk factors, and younger age at the time of RT, particularly <30 years, which confers a markedly elevated lifetime risk [47]. Tumor types historically associated with higher cardiac radiation exposure such as Hodgkin lymphoma, left-sided breast cancer, and esophageal cancer are automatically flagged for enhanced and more prolonged surveillance given their propensity to involve critical cardiac structures during treatment.

ESC recommends a baseline echocardiogram before treatment, with reassessment at 1 year, 5 years, and every 5 years thereafter for moderate risk. High-risk survivors require earlier and more frequent imaging, ideally with GLS-based strain or CMR to detect subclinical dysfunction. Coronary evaluation (CCTA or functional stress testing) is advised for symptomatic survivors or those with high LAD/substructure dose.

ASCO Recommendations

ASCO’s cardio-oncology recommendations emphasize combination therapy as the dominant risk amplifier. The interaction between anthracyclines and RT particularly mediastinal RT significantly raises risk of late LV dysfunction and heart failure, and therefore ASCO considers these patients equivalent to “high-risk” even with modest MHD [48].

Routine post-therapy echocardiography at 6–12 months is recommended for high-risk survivors, with additional imaging dictated by symptoms, abnormal baseline studies, or persistent biomarker elevation. ASCO strongly prioritizes aggressive management of traditional CV risk factors, noting that hypertension and dyslipidemia accelerate RIHD progression independently of radiation dose.

Table 1: Diagnostic Contributions of Multimodality Cardiovascular Imaging

|

Imaging Modality |

Primary Pathologies Detected |

Strengths |

Limitations |

|

TTE with GLS |

Subclinical systolic/diastolic dysfunction; pericardial effusion; early valvular changes |

Widely available; inexpensive; ideal for serial monitoring; early detection via GLS |

Window limitations; limited fibrosis/ microvascular assessment |

|

Cardiac MRI (LGE, T1/T2, ECV) |

Focal/diffuse fibrosis; edema; ventricular dysfunction |

Gold-standard for volumes/function; excellent tissue characterization |

High cost; contraindications; long acquisition |

|

Coronary CT Angiography (CCTA) |

Proximal LAD/ostial lesions; fibrocalcific plaque |

High spatial resolution; detects early CAD; CAC scoring |

Contrast required; radiation; motion artifacts |

|

Nuclear Imaging (SPECT/PET) |

Perfusion defects; inflammation; microvascular dysfunction |

Functional assessment; PET quantifies MBF/MFR |

Radiation; lower resolution; high cost |

|

CMR-derived Strain |

Global/regional deformation abnormalities |

Excellent when echo windows are poor |

Limited availability; cost |

|

ECG |

Conduction disease; arrhythmias |

Simple, inexpensive, ideal for long-term surveillance |

No structural/functional assessment |

Abbreviations: TTE: transthoracic echocardiography; GLS: global longitudinal strain; CMR: cardiac magnetic resonance; LGE: late gadolinium enhancement; ECV: extracellular volume; CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography; LAD: left anterior descending artery; CAC: coronary artery calcium; SPECT: single-photon emission computed tomography; PET: positron emission tomography; MBF: myocardial blood flow; MFR: myocardial flow reserve; ECG: electrocardiogram.

Where ESC provides detailed dosimetric cut offs, ASCO relies more on treatment-based and patient-based risk, making its approach broadly applicable even when dosimetry data are unavailable

NCCN Survivorship Guidelines

NCCN classifies thoracic RT survivors as at increased risk for premature coronary artery disease, valvular pathology, pericardial disorders, and heart failure. Although NCCN does not stratify by explicit MHD thresholds, the guideline labels mediastinal RT, childhood/AYA radiation, and left- sided breast fields as major long-term risk categories [49].

For long-term (>10 years) survivors, NCCN recommends periodic ischemia assessment, either via stress testing or coronary CT, beginning around 5–10 years post-RT depending on risk profile and symptoms. Echocardiography is advised when dyspnea, edema, chest discomfort, or new murmurs develop. Compared with ESC, NCCN focuses more on survivorship care and practical long-term monitoring rather than detailed imaging intervals.

Across ESC, ASCO, NCCN, and prior ESC statements, a unifying principle emerges: surveillance must be risk adapted, lifespan oriented, and multimodal. ESC provides the most granular dose-stratified algorithm; ASCO highlights therapy interactions and early imaging; NCCN centers on long-term survivorship; and foundational reviews define the biologic and epidemiologic basis for follow-up intensity. Together, these frameworks support individualized strategies based on MHD, anthracycline exposure, CV risk factors, age, and tumor-specific RT fields, enabling earlier detection and prevention of RIHD.

Proposed imaging-based surveillance pathway Baseline pre-RT evaluation

All patients undergoing thoracic RT particularly those with a mean heart dose (MHD) ≥5 Gy, left-sided or mediastinal fields, or concurrent anthracycline exposure should receive a comprehensive pre-treatment cardiovascular assessment. This evaluation includes a 12-lead ECG to document rhythm, conduction intervals, and baseline repolarization features [47,49], as well as transthoracic echocardiography with quantitative LVEF and global longitudinal strain to establish a reference point for detecting future subclinical dysfunction [47]. A full cardiovascular risk review covering hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and smoking status is essential, and biomarkers such as troponin and NT-proBNP should be obtained in patients receiving anthracyclines or those with pre-existing cardiovascular disease to help identify heightened susceptibility [47,48]. Establishing this baseline is critical for accurately interpreting any subsequent imaging, biomarker, or clinical changes that may emerge during or after radiotherapy.

Early post-RT phase (6–12 months)

High- and intermediate-risk survivors benefit from repeat TTE + GLS approximately 6–12 months after RT completion. A >15% relative reduction in GLS from baseline is considered an early sign of subclinical injury even when LVEF is preserved and should prompt closer follow-up or escalation to advanced imaging [47,49]. Biomarker elevation in this period similarly warrants further assessment [47].

Intermediate phase (1–5 years)

Between 1 and 5 years after RT, surveillance is guided by the patient’s risk category. Individuals at moderate to high risk should undergo annual transthoracic echocardiography with global longitudinal strain to detect early functional decline [47], whereas low-risk patients those with MHD <5 Gy, no cardiotoxic systemic therapy, and minimal cardiovascular risk factors may be adequately monitored with TTE every 3–5 years [49]. If symptoms develop or if echocardiography reveals borderline or worsening parameters, cardiac MRI becomes the modality of choice to confirm ventricular function, quantify focal fibrosis with late gadolinium enhancement, assess diffuse interstitial remodeling via T1 mapping and extracellular volume fraction, or evaluate pericardial involvement [47,49]. Functional ischemia testing, using stress echocardiography or stress CMR, is recommended for symptomatic survivors or for those who received substantial LAD radiation exposure, where occult epicardial or microvascular ischemia is a concern [35].

Late phase (>5 years)

After five years, chronic radiation sequelae such as coronary disease, valvular degeneration, and restrictive myocardial phenotypes become increasingly prevalent [49,35]. In high-risk survivors, coronary CT angiography every 5–7 years can be considered to identify proximal LAD involvement, ostial lesions, or accelerated calcification suggestive of radiation-associated coronary pathology [35]. Cardiac MRI at intervals of 3–5 years is appropriate for patients with high mean heart dose, combined anthracycline exposure, younger age at the time of RT, or any previously abnormal imaging, as it allows longitudinal assessment of ventricular function, fibrosis, and evolving tissue-level changes [47,49]. Across all risk categories, annual ECG and clinical follow-up remain essential to detect new conduction disturbances, arrhythmias, or pericardial complications, which may emerge slowly but carry significant prognostic implications [47]. The proposed imaging-based follow-up across baseline, early, intermediate, and late phases according to patient risk category is outlined in Table 2.

Table 2: Risk-Adapted Cardiac Surveillance After Thoracic Radiotherapy.

|

Risk Category |

Definition |

Baseline (Before RT) |

Early Phase (6–12 Months Post-RT) |

Intermediate Phase (1–5 Years) |

Late Phase (>5 Years) |

|

High Risk |

MHD >15 Gy; LAD dose >20 Gy; mediastinal RT; combined anthracycline therapy; age <30; multiple CV risk factors |

TTE + GLS, ECG, CV risk assessment; troponin/BNP as needed |

TTE + GLS; CMR if abnormal or symptomatic |

Annual TTE + GLS; stress imaging/CMR as indicated |

CCTA every 5–7 yrs; CMR every 3–5 yrs; annual ECG & clinical exam |

|

Moderate Risk |

MHD 5–15 Gy; moderate LAD dose; limited CV risk |

TTE + GLS, ECG |

TTE at 6–12 months |

Annual TTE + GLS |

TTE every 2–3 yrs; imaging per symptoms |

|

Low Risk |

MHD <5 Gy; right-sided RT; no cardiotoxic therapy; low CV risk |

Baseline TTE if indicated |

Clinical follow-up |

TTE every 3–5 yrs |

TTE every 5 yrs; further imaging only if symptoms |

Abbreviations: RT: radiotherapy; MHD: mean heart dose; LAD: left anterior descending artery; CV: cardiovascular; TTE: transthoracic echocardiography; GLS: global longitudinal strain; ECG: electrocardiogram; CMR: cardiac magnetic resonance; CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography; BNP: B-type natriuretic peptide.

Role of biomarkers

Circulating biomarkers provide a low-cost, repeatable adjunct to imaging for surveillance of patients receiving thoracic radiotherapy (RT), but their use in RT specific cardiotoxicity remains largely exploratory. High-sensitivity cardiac troponins (hs-cTn) and natriuretic peptides are the most extensively studied: in a large prospective NSCLC cohort treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy, serial hs-cTnT elevations during RT were tightly correlated with mean heart dose and heart V5–V55 and independently predicted subsequent grade ≥3 cardiac events and mortality, suggesting that on-treatment Δhs-cTnT can serve as an early damage signal in high-dose settings [50]. Prospective longitudinal RT studies in mixed thoracic malignancies similarly show dose-dependent changes in cardiovascular biomarkers; in particular, NT-proBNP, hs- cTnT, placental growth factor, and GDF-15 rise in patients with higher cardiac exposure, although the magnitude of change is modest and often not clearly linked to short- term changes in LV function [51,52]. In early breast cancer treated with hypofractionated adjuvant RT, NT-proBNP and hs-cTnI measurements have yielded conflicting results: some series report transient BNP/NT-proBNP increases related to left-sided irradiation, while others fail to demonstrate a robust association with acute clinical or subclinical cardiotoxicity, underscoring that single- marker approaches may lack sensitivity and specificity in contemporary low–to-moderate-dose RT regimens [53]. Beyond acute injury markers, fibrosis and stress-related biomarkers such as galectin-3 and soluble ST2 (sST2) reflect extracellular matrix remodeling and have shown prognostic value in heart failure and anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy; in one prospective anthracycline cohort, rising sST2 and galectin-3 were associated with incident CTRCD and GLS decline, whereas NT-proBNP and hs-cTnI were less informative, suggesting that multi-marker panels targeting complementary pathways may better capture early myocardial remodeling than traditional biomarkers alone [54]. Contemporary cardio-oncology reviews support integrating biomarker panels (hs-cTn, natriuretic peptides, sST2, galectin-3, and inflammatory markers) with sensitive imaging tools such as LV global longitudinal strain (GLS), right-ventricular strain, and CMR T1/T2 mapping; combined strategies consistently improve discrimination for subclinical CTRCD compared with either imaging or biomarkers alone and may be particularly valuable for triaging high-risk patients exposed to large cardiac RT doses to intensified surveillance or cardioprotective therapy [55,56]. Nevertheless, several limitations restrict the use of biomarkers as stand-alone tools for RT-specific injury: available studies are relatively small, heterogeneous in cancer type, RT technique, concomitant systemic therapy, assay platforms, and sampling schedules, and often report only small absolute biomarker changes with inconsistent relationships to long-term clinical events or imaging defined RIHD [51,53,56,57]. Moreover, hs-cTn and natriuretic peptides are influenced by pre-existing coronary disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, pulmonary hypertension, and systemic inflammation, while galectin-3 and sST2 lack tissue and disease specificity; none of these markers has an accepted RT specific threshold or timing protocol, and current cardio-oncology guidance therefore positions biomarkers as adjuncts rather than primary screening tools after thoracic RT, best interpreted in conjunction with imaging findings, baseline cardiovascular risk, and cumulative RT/ systemic therapy exposure [55-57].

Integration of Imaging with Radiotherapy Planning

Integration of cardiac imaging with radiotherapy (RT) planning has shifted from “draw the heart as one blob” to a genuinely anatomy-driven, risk-adapted process. Dedicated pre-RT contouring of the whole heart and substructures atria, ventricles, valves, pericardium and especially the coronary arteries using standardized atlases, cardiac CT and, when available, CMR, allows planners to set explicit dose constraints and to visualize where hot spots intersect with vulnerable anatomy, rather than relying solely on mean heart dose [58]. For left-sided breast cancer, CT-simulation in Deep Inspiration Breath Hold (DIBH) is now a cornerstone heart-sparing technique: lung inflation and diaphragmatic descent displace the heart away from tangential fields, consistently lowering mean heart and LAD doses without compromising target coverage [59]. In patients requiring large fields or internal mammary nodal irradiation, proton therapy adds another layer of cardioprotection by exploiting the Bragg peak to reduce integral dose and high-dose volumes to the heart and LAD compared with optimized photon plans [60,61]. Coronary-focused planning is further refined by ECG-gated CT or coronary CT angiography, which map the three- dimensional trajectory and motion envelope of the LAD and other coronaries; these datasets enable robust “internal risk volume” margins and beam arrangements that deliberately steer high-dose regions away from the proximal LAD and major bifurcations [62,63]. Emerging MR-guided RT and online adaptive workflows extend this concept into the time domain: real time soft tissue visualization and daily on table reoptimization allow smaller margins around both tumor and cardiac structures, dynamically trading target conformity against heart sparing as anatomy and filling states change over a multi-week course [64]. Finally, predictive imaging markers regional strain abnormalities, T1/T2-mapping and extracellular volume on CMR, or PET based radiomics and molecular imaging signatures of inflammation and fibrosis are beginning to close the loop between planning and surveillance: segments showing early, dose dependent injury may in future trigger plan adaptation (e.g., preferential use of DIBH or protons, tighter LAD constraints) and more intensive cardiac follow-up, pushing RT toward a truly personalized cardio- oncologic paradigm [65-67].

Management Implications of Imaging Findings

Imaging-derived evidence of early cardiac injury after thoracic radiotherapy increasingly pushes clinical decision- making toward a preventive cardiology model in which subclinical abnormalities are treated as opportunities for intervention rather than findings to be merely observed. When strain impairment, rising native T1, early pericardial enhancement, or CCTA-detected coronary plaque progression are identified, aggressive risk-factor control becomes the backbone of management: LDL-cholesterol targets consistent with secondary prevention, strict blood- pressure optimization, and tight glycemic control all appear to mitigate long-term RT-related cardiovascular disease, particularly in patients with pre-existing risk factors or those exposed to high cardiac doses [68]. Imaging abnormalities also provide a framework for evaluating emerging anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory strategies such as TGF-β pathway inhibition, renin-angiotensin system modulation, and agents targeting oxidative stress which have demonstrated biologic plausibility in preclinical and early translational studies, though none are yet established for routine post RT cardioprotection [21]. In patients with imaging-defined coronary involvement, CCTA enables precise grading of plaque burden, stenosis, and high-risk plaque characteristics; when progressive or obstructive disease is demonstrated, management follows established CAD pathways, including intensified lipid lowering, antianginal therapy, or revascularization depending on anatomical and functional significance [69]. Likewise, imaging-detected pericardial thickening, constrictive physiology, valvular fibrosis, or progressive calcification may appropriately trigger early surgical consultation, because timely intervention often prevents irreversible hemodynamic deterioration [16]. These management decisions increasingly rely on structured cardio-oncology care pathways, which integrate multimodality imaging, biomarkers, and longitudinal clinical follow-up into predefined intervals of surveillance. Patients at highest risk those receiving high heart or LAD doses, combined chemoradiation, or with significant baseline cardiovascular disease benefit most from such coordinated care, where imaging findings directly guide escalation of preventive therapy, specialist referral, and individualized monitoring intensity [70].

CONCLUSION

Radiation-related cardiotoxicity is now recognized as a major long-term consequence of thoracic cancer treatment, shaping morbidity and mortality across a growing population of survivors. The cardiovascular effects of radiotherapy span coronary disease, myocardial dysfunction, valvular and pericardial injury, and microvascular damage, forming a broad spectrum of pathology that mayevolvesilentlyforyearsbefore becoming clinically evident. In this landscape, multimodality imaging stands at the center of early detection: echo-derived strain, CCTA for coronary assessment, cardiac MRI tissue characterization, and selected nuclear techniques together provide a sensitive and complementary view of subclinical injury long before declines in ejection fraction or the onset of symptoms. Yet detection is only the first step. Because cardiac radiation exposure, baseline risk factors, systemic therapy combinations, and patient- specific susceptibilities differ widely, surveillance cannot follow a uniform template; instead, it must be individualized, with higher-risk patients receiving more intensive and prolonged monitoring. Despite meaningful advances, important uncertainties persist. Optimal follow- up intervals remain ill-defined, imaging thresholds that should prompt preventive or therapeutic intervention are not firmly validated, and the mechanistic links between dose, inflammation, fibrosis, and late events require more rigorous investigation. Integrating imaging with biomarkers, radiomics, and machine-learning–driven risk prediction offers promising avenues for future refinement. Continued prospective research, standardized imaging frameworks, and coordinated cardio-oncology care pathways will be essential to reduce the burden of radiation-induced cardiac disease and to move toward more precise, personalized prevention.

CONTRIBUTORSHIP

All of the authors contributed planning, conduct, and reporting of the work. All authors had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

REFERENCES

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021: 71: 209-249.

- Darby SC, Ewertz M, McGale P, Bennet AM, Blom Goldman U, Bronnum D, et al. Risk of ischemic heart disease in women after radiotherapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368: 987-998.

- Wang H, Wei J, Zheng Q, Meng L, Xin Y, Yin X, et al. Radiation- induced heart disease: a review of classification, mechanism and prevention. Int J Biol Sci. 2019; 15: 2128-2138.

- Chang H, Okwuosa T, Scarabelli T, Okwuosa TM, Yeh ET. Cardiovascular Complications of Cancer Therapy: Best Practices in Diagnosis, Prevention, and Management: Part 2. JACC. 2017; 70: 2552-2565.

- Ellahham S, Khalouf A, Elkhazendar M, Dababo N, Manla Y. An overview of radiation-induced heart disease. Radiation Oncol J. 2022; 40: 89-102.

- Zureick AH, Grzywacz VP, Almahariq MF, Silverman BR, Vayntraub A, Chen PY, et al. Dose to the Left Anterior Descending Artery Correlates With Cardiac Events After Irradiation for Breast Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2022; 114: 130-139.

- Locquet M, Jacob S, Geets X, Beaudart C. Dose-volume predictors of cardiac adverse events after high-dose thoracic radiation therapy for lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2024; 24: 1556.

- Taparra K, Lester SC, Harmsen WS, Petersen M, Funk RK, Blanchard MA, et al. Reducing Heart Dose with Protons and Cardiac Substructure Sparing for Mediastinal Lymphoma Treatment. Int J Part Ther. 2020; 7: 1-12.

- Bergom C, Bradley JA, Ng AK, Samson P, Robinson C, Lopez-Mattei J, et al. Past, Present, and Future of Radiation-Induced Cardiotoxicity: Refinements in Targeting, Surveillance, and Risk Stratification. JACC Cardio Oncol. 2021; 3: 343-359.

- Wolf CM, Reiner B, Kühn A, Hager A, Müller J, Meierhofer C, et al. Subclinical Cardiac Dysfunction in Childhood Cancer Survivors on 10-Years Follow-Up Correlates With Cumulative Anthracycline Dose and Is Best Detected by Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing, Circulating Serum Biomarker, Speckle Tracking Echocardiography, and Tissue Doppler Imaging. Front Pediatr. 2020; 8: 123.

- Koutroumpakis E, Deswal A, Yusuf SW, Abe JI, Nead KT, Potter AS, et al. Radiation-Induced Cardiovascular Disease: Mechanisms, Prevention, and Treatment. Curr Oncol Rep. 2022; 24: 543-553.

- Xu S, Donnellan E, Desai MY. Radiation-Associated ValvularDisease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020; 22: 167.

- Wang SY, Lin KH, Wu YW, Yu CW, Yang SY, Shueng PW, et al. Evaluation of the cardiac subvolume dose and myocardial perfusion in left breast cancer patients with postoperative radiotherapy: a prospective study. Sci Rep. 2023; 13: 10578.

- Lyon AR, López-Fernández T, Couch LS, Asteggiano R, Aznar MC, Bergler-Klein J, et al. 2022 ESC Guidelines on cardio-oncology developed in collaboration with the European Hematology Association (EHA), the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO) and the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS). Eur Heart J. 2022; 43: 4229-4361.

- Patil S, Pingle SR, Shalaby K, Kim AS. Mediastinal irradiation andvalvular heart disease. Cardiooncology. 2022; 8: 7.

- Mitchell JD, Cehic DA, Morgia M, Bergom C, Toohey J, Guerrero PA, et al. Cardiovascular Manifestations From Therapeutic Radiation: A Multidisciplinary Expert Consensus Statement From the International Cardio-Oncology Society. JACC Cardio Oncol. 2021; 3: 360-380.

- Mori S, Bertamino M, Guerisoli L, Stratoti S, Canale C, Spallarossa P, et al. Pericardial effusion in oncological patients: current knowledge and principles of management. Cardiooncology. 2024; 10: 8.

- Lorenzo-Esteller L, Ramos-Polo R, Pons Riverola A, Morillas H, Berdejo J, Pernas S, Pomares H, et al. Pericardial Disease in Patients with Cancer: Clinical Insights on Diagnosis and Treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2024; 16: 3466.

- Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, Badano L, Barón-Esquivias G, Bogaert J, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Endorsed by: The European Association for Cardio- Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2015; 36: 2921-2964.

- Pahwa S, Crestanello J, Miranda W, Bernabei A, Polycarpou A, Schaff H, et al. Outcomes of pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis following mediastinal irradiation. J Card Surg. 2021; 36: 4636-4642.

- Narowska G, Gandhi S, Tzeng A, Hamad EA. Cardiovascular Toxicities of Radiation Therapy and Recommended Screening and Surveillance. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2023;10: 447.

- Bedi R, Ahmad A, Horbal P, Mar PL. Radiation-associated Arrhythmias: Putative Pathophysiological Mechanisms, Prevalence, Screening and Management Strategies. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2023; 12: e24.

- Zhang DM, Navara R, Yin T, Szymanski J, Goldsztejn U, Kenkel C, et al. Cardiac radiotherapy induces electrical conduction reprogramming in the absence of transmural fibrosis. Nat Commun. 2021; 12: 5558.

- Wu S, Guan W, Zhao H, Li G, Zhou Y, Shi B, et al. Assessment of short-term effects of thoracic radiotherapy on the cardiovascular parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems. Front Neurosci. 2023; 17: 1256067.

- Noor B, Akhavan S, Leuchter M, Yang EH, Ajijola OA. Quantitative assessment of cardiovascular autonomic impairment in cancer survivors: a single center case series. Cardiooncology. 2020; 6: 11.

- Siaravas KC, Katsouras CS, Sioka C. Radiation Treatment Mechanismsof Cardiotoxicity: A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24: 6272.

- Armstrong GT, Joshi VM, Ness KK. Comprehensive Echocardiographic Detection of Treatment-Related Cardiac Dysfunction in Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer: Results From the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015; 65: 2511-2522.

- Plana JC, Galderisi M, Barac A, Ewer MS, Ky B, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Ganame J, et al. Expert consensus for multimodality imaging evaluation of adult patients during and after cancer therapy: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014; 15: 1063-1093.

- Yusuf SW, Sami S, Daher IN. Radiation-induced heart disease: aclinical update. Cardiol Res Pract. 2011; 2011: 317659.

- Ricco A, Slade A, Canada JM, Grizzard J, Dana F, Gharai LR, et al. Cardiac MRI utilizing late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) and T1 mapping in the detection of radiation induced heart disease. Cardiooncology. 2020; 6: 6.

- Harries I, Liang K, Williams M, Berlot B, Biglino G, Lancellotti P, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging to Detect Cardiovascular Effects ofCancer Therapy: JACC CardioOncology State-of-the-Art Review. JACC Cardio Oncol. 2020; 2: 270-292.

- Burrage MK, Ferreira VM. The use of cardiovascular magnetic resonance as an early non-invasive biomarker for cardiotoxicity in cardio-oncology. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2020; 10: 610-624.

- Ferreira VM, Schulz-Menger J, Holmvang G, Kramer CM, Carbone I, Sechtem U, et al. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Nonischemic Myocardial Inflammation: Expert Recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72: 3158-3176.

- Gallone G, Bellettini M, Gatti M, Tore D, Bruno F, Scudeler L, et al. Coronary Plaque Characteristics Associated With Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Atherosclerotic Patients and Lesions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2023; 16: 1584-1604.

- Jaworski C, Mariani JA, Wheeler G, Kaye DM. Cardiac complications ofthoracic irradiation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 61: 2319-2328.

- Wennstig AK, Garmo H, Wadsten L, Lagerqvist B, Fredriksson I, Holmberg L, et al. Risk of coronary stenosis after adjuvant radiotherapy for breast cancer. Strahlenther Onkol. 2022; 198: 630-638.

- Corbett T. Radiation Dose Reduction Strategies in CoronaryCTA. Radiol Technol. 2020; 91: 404-406.

- Jo IY, Lee JW, Kim WC, Min CK, Kim ES, Yeo SG, et al. Relationship Between Changes in Myocardial F-18 Fluorodeoxyglucose Uptake and Radiation Dose After Adjuvant Three-Dimensional Conformal Radiotherapy in Patients with Breast Cancer. J Clin Med. 2020; 9: 666.

- Unal K, Unlu M, Akdemir O, Akmansu M. 18F-FDG PET/CT findings of radiotherapy-related myocardial changes in patients with thoracic malignancies. Nucl Med Commun. 2013; 34: 855-859.

- Chau OW, Islam A, Lock M, Yu E, Dinniwell R, Yaremko B, et al. PET/ MRI Assessment of Acute Cardiac Inflammation 1 Month After Left- Sided Breast Cancer Radiation Therapy. J Nucl Med Technol. 2023; 51: 133-139.

- Groarke JD, Divakaran S, Nohria A, Killoran JH, Dorbala S, Dunne RM, et al. Coronary vasomotor dysfunction in cancer survivors treated with thoracic irradiation. J Nucl Cardiol. 2021; 28: 2976-2987.

- Pelletier-Galarneau M, Martineau P, El Fakhri G. Quantification of PET Myocardial Blood Flow. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2019; 21: 11.

- Thavendiranathan P, Poulin F, Lim KD, Plana JC, Woo A, Marwick TH. Use of myocardial strain imaging by echocardiography for the early detection of cardiotoxicity in patients during and after cancer chemotherapy: a systematic review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 63: 2751-2768.

- Sammut EC, Villa ADM, Di Giovine G, Dancy L, Bosio F, Gibbs T, et al. Prognostic Value of Quantitative Stress Perfusion Cardiac Magnetic Resonance. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018; 11: 686-694.

- Lancellotti P, Suter TM, López-Fernández T, Galderisi M, Lyon AR, Van der Meer P, et al. Cardio-Oncology Services: rationale, organization, and implementation. Eur Heart J. 2019; 40: 1756-1763.

- Armenian SH, Lacchetti C, Barac A, Carver J, Constine LS, Denduluri N, et al. Prevention and Monitoring of Cardiac Dysfunction in Survivors of Adult Cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017; 35: 893-911.

- Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Rodriguez Muñoz D, Aboyans V, Asteggiano R, Galderisi M, et al. 2016 ESC Position Paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines: The Task Force for cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016; 37: 2768-2801.

- Xu T, Meng QH, Gilchrist SC, Lin SH, Lin R, Xu T, et al. Assessment of Prognostic Value of High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin T for Early Prediction of Chemoradiation Therapy-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Secondary Analysis of a Prospective Randomized Trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021; 111: 907-916.

- Beukema JC, Haveman JW, Langendijk JA, Oldehinkel E, van den Bergh ACM, de Haan JJ, et al. Blood biomarkers for cardiac damage during and after radiotherapy for esophageal cancer: A prospective cohort study. Radiother Oncol. 2024; 200: 110479.

- Demissei BG, Freedman G, Feigenberg SJ, Plastaras JP, Maity A, Smith AM, et al. Early Changes in Cardiovascular Biomarkers with Contemporary Thoracic Radiation Therapy for Breast Cancer, Lung Cancer, and Lymphoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019; 103: 851- 860.

- De Sanctis V, Alfò M, Vitiello C, Vullo G, Facondo G, Marinelli L, et al. Markers of Cardiotoxicity in Early Breast Cancer Patients Treated With a Hypofractionated Schedule: A Prospective Study. Clin Breast Cancer. 2021; 21: e141-e149.

- Shirzadi S, Borazjani R, Attar A. Efficacy of Novel Cardiac Biomarkers in Detecting Anthracycline- Induced Cardiac Toxicity.Int Cardiovasc Res J. 2021; 15: e116347.

- Zhang X, Sun Y, Zhang Y, Fang F, Liu J, Xia Y, et al. Cardiac Biomarkers for the Detection and Management of Cancer Therapy-Related Cardiovascular Toxicity. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2022; 9: 372.

- Michel L, Rassaf T, Totzeck M. Biomarkers for the detection of apparent and subclinical cancer therapy-related cardiotoxicity. J Thorac Dis. 2018; 10: S4282-S4295.

- Palaskas N, Patel A, Yusuf SW. Radiation and cardiovascular disease.Ann Transl Med. 2019; 7: S371.

- Finnegan RN, Quinn A, Booth J, Belous G, Hardcastle N, Stewart M, et al. Cardiac substructure delineation in radiation therapy - A state-of- the-art review. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2024; 68: 914-949.

- Hayden AJ, Rains M, Tiver K. Deep inspiration breath hold technique reduces heart dose from radiotherapy for left-sided breast cancer. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2012; 56: 464-472.

- Lin LL, Vennarini S, Dimofte A, Ravanelli D, Shillington K, Batra S, et al. Proton beam versus photon beam dose to the heart and leftanterior descending artery for left-sided breast cancer. Acta Oncol.2015; 54: 1032-1039.

- Nangia S, Burela N, Noufal MP, Patro K, Wakde MG, Sharma DS. Proton therapy for reducing heart and cardiac substructure doses in Indian breast cancer patients. Radiat Oncol J. 2023; 41: 69-80.

- Kataria T, Bisht SS, Gupta D, Abhishek A, Basu T, Narang K, et al. Quantification of coronary artery motion and internal risk volume from ECG gated radiotherapy planning scans. Radiother Oncol. 2016; 121: 59-63.

- Lester, Scott C. Electrocardiogram-Gated Computed Tomography with Coronary Angiography for Cardiac Substructure Delineation and Sparing in Patients with Mediastinal Lymphomas Treated with Radiation Therapy. Practical Radiation Oncol. Volume 10, Issue 2, 104 -111

- Nierer L, Eze C, da Silva Mendes V. Dosimetric benefit of MR-guided online adaptive radiotherapy in different tumor entities: liver, lung, abdominal lymph nodes, pancreas and prostate. Radiat Oncol. 2022; 17: 53.

- Omidi A, Weiss E, Trankle CR. Quantitative assessment of radiotherapy-induced myocardial damage using MRI: a systematic review. Cardio-Oncology. 2023; 9: 24.

- Walls GM, Bergom C, Mitchell JD, Rentschler SL, Hugo GD, Samson PP, et al. Cardiotoxicity following thoracic radiotherapy for lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2025; 132: 311-325.

- Kersting D, Mavroeidi IA, Settelmeier S, Seifert R, Schuler M, Herrmann K, et al. Molecular Imaging Biomarkers in Cardiooncology: A View on Established Technologies and Future Perspectives. J Nucl Med. 2023; 64: 29S-38S.

- Wilson J, Jun Hua C, Aziminia N, Manisty C. Imaging of the Acute and Chronic Cardiovascular Complications of Radiation Therapy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2025; 18: e017454.

- Groarke JD, Nguyen PL, Nohria A, Ferrari R, Cheng S, Moslehi J. Cardiovascular complications of radiation therapy for thoracic malignancies: the role for non-invasive imaging for detection of cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2014; 35: 612-623.

- Pedersen LN, Schiffer W, Mitchell JD, Bergom C. Radiation- induced cardiac dysfunction: Practical implications. Polish Heart J (Kardiologia Polska). 2022; 80: 256-265.