Hepatic Lobar and Segmental Agenesis or Hypoplasia: CT Features

- 1. Department of Radiology, University of California-San Diego Medical Center, USA

Abstract

Agenesis or hypoplasia of the liver lobes are very uncommon developmental anomalies and can be recognized on CT examinations. These are usually asymptomatic and incidental finding, but they cause an altered topography and anatomical relationship of the upper abdominal organs. This can lead to various complications, particularly during the surgical or interventional procedures involving the liver or gallbladder. The CT appearance of these anomalies and their clinical implications are presented in this article, and differential diagnosis from acquired liver atrophy due to various pathological processes is also discussed.

Keywords

Liver anomalies; Computed tomography; Hepatic lobe agenesis; Segmental hypoplasia; Ectopic gallbladder; Malposition of the colon; Gastric volvulus

Citation

Ghahremani GG, Hahn ME (2023) Hepatic Lobar and Segmental Agenesis or Hypoplasia: CT Features. J Radiol Radiat Ther 11(1): 1096.

HIGHLIGHTS

- Anomalies of hepatic lobes are rare and occur in 0.005% of individuals.

- Most are asymptomatic and incidental finding on imaging studies.

- Agenesis or hypoplasia of the left lobe causes displacement and excessive mobility of the stomach.

- It may lead to development of hiatal hernia and gastric volvulus.

- Right hepatic lobe anomaly is associated with ectopic gallbladder and hepato-diaphragmatic interposition of the colon.

- Their recognition can be crucial in preoperative planning and preventing iatrogenic mishaps.

INTRODUCTION

Congenital anomalies of the liver are rare and reported to occur with an incidence of 0.005% in 19,000 postmortem examinations [1-3]. The observed manifestations are agenesis or hypoplasia of a hepatic lobe or its segments. These were previously recognized only at surgery or autopsy. However, the introduction of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has allowed the in vivo detection of these uncommon anomalies [4-8].

The CT diagnosis of hepatic lobar agenesis or hypoplasia is important because they alter the anatomic location and relationships of the upper abdominal organs. They may complicate the performance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, hepatectomy, or liver transplantation, and can be associated with various other abdominal disorders [2,9-12].

A search of Medline data base through PubMed reveals that fewer than one hundred isolated cases or small series of these liver anomalies have been reported in the medical literature, primarily in the surgical and clinical journals [1-3,9-11]. However, a more comprehensive review of this subject has not appeared in the radiological publications. The purpose of this article is to illustrate the spectrum of CT findings of hepatic lobe agenesis or hypoplasia, and to review the pertinent literature about their etiology and clinical significance.

PATHOGENESIS OF LIVER ANOMALIES

The liver is an important accessory digestive organ that exists only in vertebrates. Its development begins in the 3rd week of human gestation from hepatic bud in the distal part of foregut and grows rapidly through maternal blood supply from placenta. After birth, the liver becomes the heaviest internal organ and largest gland in the body by receiving up to 25% of total cardiac output. Its dual blood supply consists of the hepatic artery which contributes 25-30% of oxygenated blood, and the portal vein delivering 70-75% of blood rich in nutrients absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract [13,14].

It has been shown that any disruption of blood supply to the liver can interfere with its normal development, causing agenesis or hypoplasia of a hepatic lobe or its segments [10,12,14]. This may occur either during the fetal growth or soon after birth. It is usually due to thrombosis of intrahepatic portal vein branches as the result of hypercoagulable states, umbilical vein catheterization, abdominal infection, malnutrition, dehydration, and other causal factors [15,16]. The extensive anatomical variations of the portal vein and hepatic arterial system also contribute to the etiology of these anomalies [17-19].

CLASSIFICATION OF HEPATIC LOBES AND SEGMENTS

The human liver is anatomically composed of the right and left lobes, as well as 2 smaller caudate and quadrate lobes located on the undersurface of the left lobe. For imaging and surgical purposes, however, the Couinaud classification is usually used [14,18,19]. It divides the liver into 8 functionally independent segments, which consist of segment 1(caudate lobe), segments 2-4(left lobe) and 5-8 (right lobe). The center of each segment contains a branch of the portal vein, hepatic artery, and bile duct, while in the periphery is the vascular outflow through the hepatic veins. Therefore, surgical resection lines that parallel the peripheral hepatic veins would leave the rest of hepatic parenchyma intact.

LEFT HEPATIC LOBE AGENESIS AND HYPOPLASIA

Agenesis of the entire left lobe has been reported in about 35 cases [1,6,10,11,20]. This anomaly causes a significant alteration of upper abdominal topography that can be readily appreciated on CT examination.

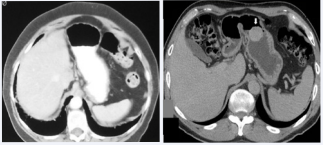

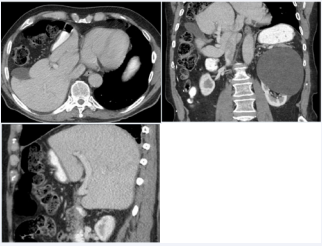

Figure 1: CT of the left hepatic lobe agenesis in 2 patients. A. Axial image of the upper abdomen in a 42-year-old woman reveals an absent left lobe, causing midline position of the stomach and protrusion of the splenic flexure in to the left subphrenic space. B. CT section of the upper abdomen in this 60-year-old man demonstrates a horizontal stomach with adjacent loop of the transverse colon. The absence of left lobe was confirmed at laparotomy for resection of the gastric GIST (arrow)

The left lobe consists of segments 2 and 3 that form its superior and inferior parts of it medial to the falciform ligament, whereas segment 4 lies lateral to it. The stomach is normally attached to the left lobe through the gastrohepatic ligament representing superior aspect of the lesser omentum. The duodenal bulb is also connected to the porta hepatis by the hepatoduodenal ligament [14].Therefore; the absence of left hepatic lobe and these attachments allows excessive mobility of the stomach. It becomes malpositioned in the midline and the vacated left upper abdomen is then occupied by the proximal jejunal loops and the splenic flexure protruding in to the left subphrenic space (Figure 1).

Figure 2: Agenesis of the left lobe complicated by gastric volvulus and its hiatal herniation in a 76-year-old woman. A, B. Coronal, and sagittal images show the right lobe of the liver but no left lobe, with a fluidfilled stomach herniating into the thorax

It has been reported that this anomaly can interfere with gastric emptying and may cause peptic ulcer disease [10]. The increased gastric mobility can also lead to development of large hiatal hernia and volvulus of the stomach [11-21] (Figure 2).

There have been several case reports of ectopic gallbladder in patients with left hepatic lobe agenesis or hypoplasia, including a floating or left-sided gallbladder in the epigastric region [22-24].

There is often a compensatory hypertrophy of the right and caudate lobes, thus maintaining the normal liver functions. These patients are usually asymptomatic unless the above-noted complications lead to the diagnosis of hepatic lobar anomaly on imaging studies [4-7]. In a patient with left lobar agenesis presented by Matsushita and associates, the three-dimensional CT revealed the absence of the left hepatic artery, left portal vein and biliary ducts [10].

Hypoplasia of the left lobe is encountered occasionally in patients undergoing CT examination for unrelated abdominal disorders. The observed findings are similar but less striking as compared to its complete agenesis.

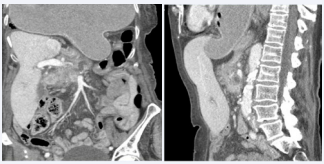

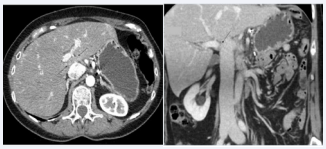

Figure 3: CT features of the left lobe hypoplasia in 2 patients. A. Axial image of the upper abdomen in this 47-year-old man demonstrates the small left lobe due to reduced size of segments 2 and 3, with gasfilled transverse colon occupying the upper abdomen. B and C. Axial and coronal images in this 36- year-old man show a concave defect in the anterior aspect of the liver caused by hypoplasia of segment 4 (arrows).

A small left lobe due to hypoplasia of segments 2 and 3 will appear as a narrow structure on the medial aspect of the liver, with some shift of the stomach towards the midline (Figure 3A). There is often a compensatory enlargement of other hepatic segments. Furthermore, the gallbladder can be ectopic and located in the left upper abdomen or floating in the epigastric area [23,24].

Segment 4 of the left lobe is located lateral to the falciform ligament, and its hypoplasia can be easily recognized on abdominal CT as a defect on the anterior aspect of the liver (Figure 3B and C). This anomaly can be a risk factor for bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy due to much smaller distance between the gallbladder and adjacent structures at the resection site [25,26].

RIGHT HEPATIC LOBE ANOMALIES

A complete absence of the right lobe is highly unusual. In fact, all 65 cases reported prior to 2018 involved the agenesis or hypoplasia of only a part of it, most notably the segments 6, 7 and 8 of the liver [2-5,26-28].

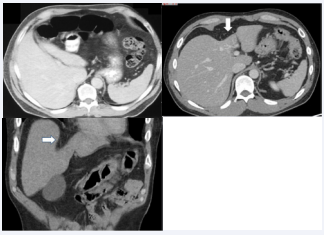

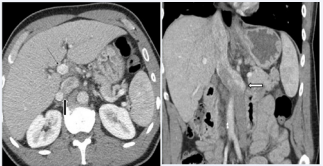

Figure 4: Segmental agenesis of the right hepatic lobe in an 82-yearold man with prostate cancer. A. Axial CT image reveals a deformed configuration of the liver due to the absence of its antero-lateral segments. The ectopic gallbladder and colon are visible in the vacated liver space. B, C. Coronal, and sagittal images show a large defect resulting from agenesis of segments 5-7 of the right lobe, where the gallbladder and hepatic flexure have occupied.

Such cases demonstrate a wedge-shaped defect on the lateral aspect of the right hepatic lobe on CT images. It is usually occupied by the hepatic flexure of the colon, which is displaced superiorly between the liver and right hemi-diaphragm (Figures 4 and 5). It presents with typical features of Chilaiditi syndrome [29]. It can be associated with right diaphragmatic eventration or Bochdalek hernia, intrathoracic right kidney, persistent right umbilical vein, and Budd-Chiari syndrome [26-28].

Figure 5: Segmental agenesis of the right lobe in a 74-year-old man. A, B. Axial and coronal CT images show a wedge-shaped defect of the liver caused by agenesis of its segment 8, occupied by the gallbladder and hepatic flexure.

Furthermore, the gallbladder is seen to be ectopic in the lateral or suprahepatic location and can be involved by cholecystitis or cholelithiasis in about 25% of the cases [2-9].This may be due to compression or torsion of the cystic duct of the displaced gallbladder. There is also an increased prevalence of portal hypertension in these patients, which has been attributed to the elevated pressure resulting from reduced number or obstruction of intrahepatic portal vein branches [26].

According to Chou et al. the diagnostic criteria for right lobar agenesis would include the absence of right portal and hepatic veins, as well as a dilatation of the left intrahepatic bile duct. In contrast, at least one of these venous structures remains visible in the case of hypoplasia [4].

The anomalous right hepatic lobe is usually associated with a compensatory enlargement of the left and caudate lobes, and normal liver functions. However, this anomaly should be differentiated from severe atrophy of the right hepatic lobe due to severe cirrhosis, cholangiocarcinoma, or prior segmental resection of the liver [4-6,26-29].

CAUDATE LOBE ANOMALIES

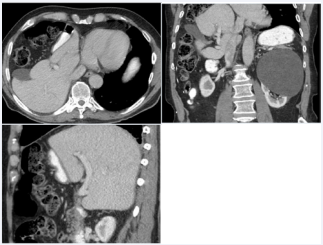

Agenesis of the caudate lobe or segment 1 of the liver is a very rare finding [29,30]. However, its hypoplasia may be encountered occasionally on CT examination. This lobe is located on the inferior surface of the liver and protrudes between the portal vein and the inferior vena cava at the porta hepatis (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Hypoplasia of the caudate lobe in a 45- year-old woman. A, B. Axial, and coronal images show a small caudate lobe projecting between the portal vein and inferior vena cava (arrows).

Complete agenesis of the caudate lobe was observed in a man with duplication of inferior vena cava, in whom the persistent left IVC was much larger than the right IVC and continued its course through the liver. This was unusual because the left IVC would typically drain into the left renal vein, which then joins the right IVC [31,32]. It is postulated that the congenital development of the caudate lobe may have been prevented by its compression in the narrowed space between the portal vein and dilated IVC (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Agenesis of the caudate lobe in a 54-year-old man with duplication of the inferior vena cava. A. Axial CT image reveals the absence of caudate lobe in the space between portal vein (small arrow) and junction of the larger left and smaller right IVC (large arrow). B. Coronal section shows a markedly dilated left IVC that continues through the liver (white arrow).

This concept was further confirmed in another case of a young man undergoing CT examination of the abdomen for jejunal intussusception complicating T-cell lymphoma, in whom a dilated IVC, gallbladder and some intestinal loops protruded into the area of absent caudate lobe. The same etiological process could also account for the hypoplasia of the caudate lobe as demonstrated in Figure 6. In fact, the anatomical studies of 20 human livers by Kogure and associates show the importance of such close relation between the caudate lobe and IVC [33].

It should be noted that the caudate lobe is unique because of its own portal blood supply and hepatic vein drainage that are separate from the rest of the liver. Therefore, it is anatomically and functionally independent and differently affected by the liver pathologies. In fact, the caudate lobe may be spared from the cirrhotic atrophy of the liver and instead undergo a compensatory hypertrophy [14,31,34].These features of caudate lobe may have significant implications for liver surgery and transplant; hence its appearance should be carefully evaluated on CT examinations [34].

DISCUSSION

The hepatic anomalies that are presented herein had a congenital or idiopathic etiology since the affected lobe or segments were not involved by any inflammatory or neoplastic lesion that could have caused their reduced size. This contrasts with the acquired atrophy resulting from various pathological processes, such as cirrhosis, portal vein thrombosis, cholangiocarcinoma, pyogenic or sclerosing cholangitis, and biliary obstruction [35,36]. Compared to the normal liver parenchyma, the atrophied parts often show a lower attenuation on pre-contrast CT and higher enhancement during the hepatic arterial phase, as well as a decreased signal intensity on T1- weighted MRI and increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images. These findings reflect the increased water content of atrophic parts due to edema, arterio-portal shunting, and fibrosis [35]. In rare instances, an atrophic part of the liver may form a pseudotumor and present as a diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma [37,38].

Despite the congenital nature of hepatic lobe agenesis or hypoplasia, these anomalies are seldom diagnosed in the pediatric age group [11].This is a somewhat surprising fact because the vascular anomalies that lead to abnormal liver development have been well documented in infants and children [15-18].

At the time of their diagnosis most patients with agenesis or hypoplasia of the liver lobes are adults, in whom these findings are discovered incidentally during CT or MRI and ultrasound studies performed for unrelated medical conditions [1-8,11,12,15]. We have illustrated their CT features in this article mainly because our experience indicates that the abnormal liver configurations are more easily appreciated on CT of the abdomen due to widespread usage of this imaging modality in clinical practice. Nevertheless, the radiological diagnosis of hepatic lobar and segmental anomaly can be important because of the potential complications resulting from distorted anatomical relationships between the upper abdominal organs.

The main concern in patients with the left hepatic lobe agenesis is the excessive mobility of the stomach due to concurrent absence of the gastrohepatic attachment. This may lead to hiatal hernia or gastric volvulus, which have been reported in both children and adults [11,21].There have been case reports of delayed gastric emptying and development of peptic ulcer complicating displacement of the stomach due to absent left lobe [10,40].

Significant complications may occur with segmental agenesis or hypoplasia of the right lobe. These are primarily related to the ectopic gallbladder, which creates difficulty during laparoscopic cholecystectomy and may cause inadvertent injury to the liver and bile ducts [2,9,12]. It should be noted that an ectopic gallbladder occurs in 0.007% to 0.13% of individuals but is more commonly associated with the right than the left hepatic lobe anomaly [22-24].

An ectopic gallbladder is predisposed to development of cholecystitis and gallstones in about 25% of cases. The reason is that the abnormal liver configuration and displacement of gallbladder will cause compression or torsion of the cystic duct, leading to bile stasis and calculus formation [2,9,22,26].

Another problem relates to the interposition of the hepatic flexure of the colon between lateral aspect of the liver defect and right hemi-diaphragm (Figures 4 and 5). It can sustain injury during percutaneous liver biopsy, gallbladder drainage, and operative procedures on the liver or biliary tract [26,27,29].

Liang et al recently reviewed the clinical findings of right hepatic lobe anomaly in 43 patients, who ranged in age from 7 to 83 years (Mean age: 59 years) [26].The authors found that this condition was associated with left or caudate lobe hypertrophy in 93% and 44% respectively, ectopic gallbladder in 96%, cholecystitis in 31% of the cases. Furthermore, the obstruction or narrowing of the right portal vein had resulted in portal hypertension in 38% of the patients. This complication was also confirmed in a comprehensive review of 31 patients by Inoue and associates [35]. It has been postulated that portal hypertension occurring with anomalous right lobe may be due to the reduced number of intrahepatic portal vein branches and increased vascular resistance within the liver parenchyma [26].

There have been several case reports of patients with hepatic lobe agenesis or hypoplasia, who had presented with cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, Budd-Chiari syndrome, or retroperitoneal fibrosis [10,12,26,28]. However, these pathological entities were most likely a coincidental finding.

It is of interest to note that we had encountered agenesis or hypoplasia of the caudate lobe in patients who had rather large or dilated inferior vena cava (Figures 6 and 7). We assume that the narrowed space between the portal vein and IVC may have interfered with the congenital development of caudate lobe in such cases. This concept is supported by anatomical studies that have documented a close relation of the caudate lobe to IVC [33- 41].

CONCLUSIONS

It is important for diagnostic radiologists and practicing clinicians to be familiar with features of hepatic lobe agenesis or hypoplasia that may be detected incidentally on imaging studies performed for various unrelated abdominal disorders. These anomalies can be associated with important coexisting complications, particularly if any surgical intervention is planned. Therefore, their presence should be clearly described in the radiological report to the referring physician. It is also important to differentiate these anomalies from acquired atrophy of the liver lobes or segments caused by various underlying pathological processes.

DECLARATIONS

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest and have no disclosure relevant to the subject matter of this article.

Ethical approval

Due to the retrospective review of the already performed and medically warranted examinations, the patients consent, and IRB approval were waived.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that they had full access to all the data in the study and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data.

REFERENCES

12. Alicioglu B. Right liver lobe hypoplasia and related abnormalities. Pol J Radiol. 2015; 80: 503-505.

14. Abdel-Misih SRZ, Bloomston M. Liver anatomy. Surg Clin North Am. 2010; 90: 643-653.

17. Albers BK, Khanna G. Vascular anomalies of the pediatric liver. RadioGraphics. 2019; 39: 842-856.

19. Choi TW, Chung JW, Kim HC, Lee M, Choi JW, Jae HJ, et al. Anatomic variations of the hepatic artery in 5625 patients. Radiology: Cardiothor Imaging. 2021; 3: 1-9 e21007.

22. Kanwal R, Akhtar S. Left hepatic lobe agenesis with ectopic gallbladder. Cureus. 2021; 13: e 16131.

36. Ham JM. Lobar and segmental atrophy of the liver. World J Surg 1990; 14: 457-462.