A Review of Laparoscopic Percutaneous Extra Peritoneal Closure (LPEC) for the Treatment of Pediatric Inguinal Hernia

- 1. Department of Surgery, Jikei University School of Medicine, Japan

ABSTRACT

Since laparoscopic percutaneous extra peritoneal closure (LPEC) was introduced as a treatment for pediatric inguinal hernia in 2000, the procedure has been the most common surgical technique for repairing pediatric inguinal hernia in Japan. Research date shows that LPEC and conventional open repair have equivalent rates of recurrence and of postoperative complications. In addition, if contra lateral patent processes vaginalis (CPPV) is confirmed, prophylactic contra lateral LPEC is useful for preventing metachronous contra lateral hernia (MCH). Recently, reduced-port surgery has been adopted throughout the laparoscopic surgery field. Two improved LPEC techniques, known as single-incision laparoscopic percutaneous extra peritoneal closure (SILPEC) and percutaneous internal ring surgery, are not significantly different from LPEC in operating time, intra operative complications or recurrence. Finally, the learning curve for surgical residents to perform the LPEC technique safely without supervision is more than 30 cases. Thus LPEC is an acceptable alternative to conventional open repair.

KEYWORDS

• Laparoscopic percutaneous extra peritoneal closure

• Pediatric inguinal hernia

• Contra lateral patent processes vaginalis

• Single-incision laparoscopic percutaneous extra

peritoneal closure

• Percutaneous internal ring surgery

• Learning curve

CITATION

Kanamori D, Yoshizawa J (2016) A Review of Laparoscopic Percutaneous Extra Peritoneal Closure (LPEC) for the Treatment of Pediatric Inguinal Hernia. J Surg Transplant Sci 4(3): 1029.

ABBREVIATIONS

LPEC: Laparoscopic Percutaneous Extra Peritoneal Closure; CPPV: Contra Lateral Patent Processes Vaginalis; MCH: Metachronous Contra Lateral Hernia; OR: Open Repair; SILPEC: Single-Incision Laparoscopic Percutaneous Extra Peritoneal Closure; SILS: Single-Incision Laparoscopic Surgery; PIRS: Percutaneous Internal Ring Surgery

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic treatment of inguinal hernias in pediatric patients was first described in 1997 by El-Gohary [1]. Initially, this procedure was performed only in female patients because the safety of the vas and vessels is of concern in male patients. Montupet and Esposito [2] were the first to report using laparoscopy in male children, in 1999. At that time, their method needed three ports to perform high ligation with the Endoloop or an intra peritoneal suture. New adaptations of fully intra corporeal techniques in both sexes have continued to evolve over the years. Nowadays, the most common surgical procedure for pediatric inguinal hernia repair in Japan, which was introduced in 2000 by Takehara et al. [3], is LPEC. Here, we review the literature to give an overview of LPEC and to evaluate the role of LPEC techniques in the operative treatment of inguinal hernias of children.

DISCUSSION & CONCLUSION

Surgical procedure

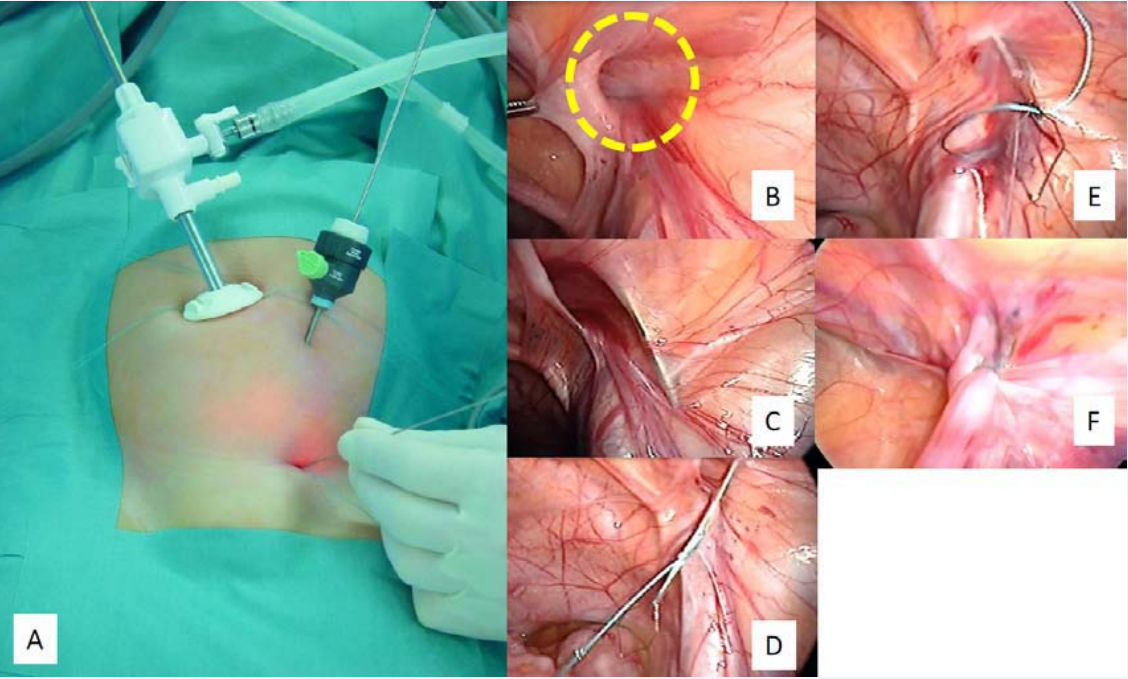

A 5-mm cannula for a 5-mm laparoscope is placed through an umbilical incision. A2-mm grasping forceps is inserted through a 2-mm trocar on the left side of the umbilicus (Figure 1A).

Figure 1: Surgical procedure. A. Through an umbilical incision we insert a laparoscope through a 5-mm trocar; at another point, we insert a grasping forceps through another trocar (2 mm). B. The yellow circle surrounds the internal inguinal ring. C. Inserting the LapahercloserTM. D. Letting go of the suture material. E. Tying the suture material. F. Pulling out the suture material.

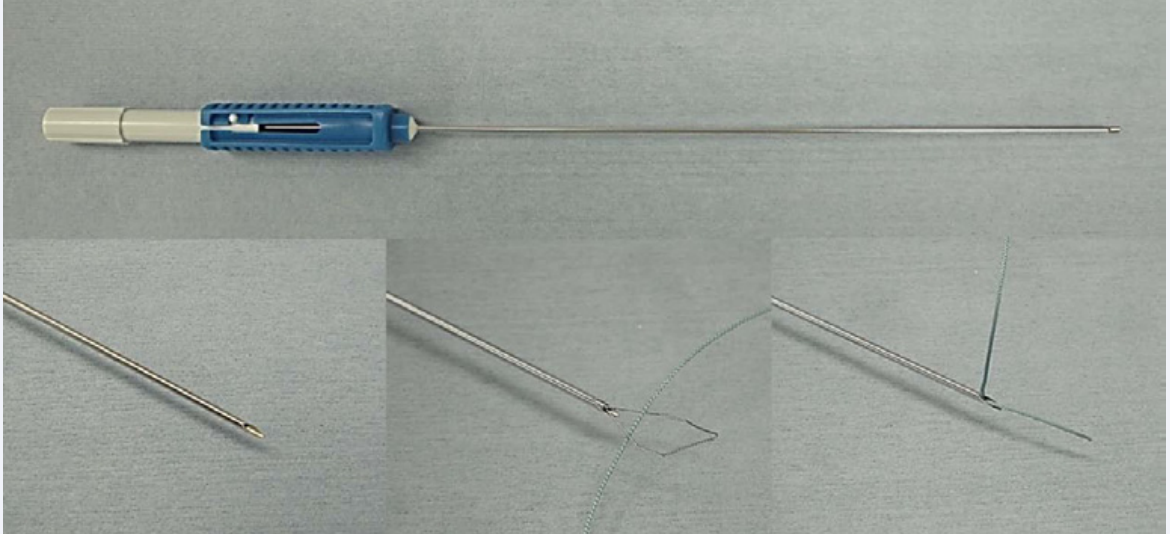

Then a 19-gauge LPEC needle (LapaherclosureTM) (Figure 2), threaded with suture material, is inserted at the midpoint of the right or left inguinal line.

Figure 2: LapaherclosureTM. The LapaherclosureTM, or LPEC needle, is a special instrument that has a wire loop at the tip to hold the suture material. It is used for circuit suturing around the internal inguinal ring (Figure 1B).

The orifice of the hernialsacis closed extraperitoneally with circuit suturing around the internal inguinal ring (Figure 1B) using the LPEC needle. Care is taken to cross over the spermatic duct or the gonadal vessels to avoid causing injury. Specifically, the first half of the circuit suturing is begun extraperitoneally from the anterior to the posterior edge of half of the internal inguinal ring using the LPEC needle with non-absorbable suture material (Figure 1C). After half of the circuit suturing is completed, the suture material is removed from the LPEC needle (Figure 1D) and left in the peritoneum. The circuit suturing of the opposite half of the rim of the internal ring is placed extraperitoneally using the same technique, the suture material in the peritoneum being picked up and held by the wire loop inside the LPEC needle (Figure 1E). The LPEC needle is then removed from the abdomen together with the suture material. The circuit suturing is tied extra corporeally, and the internal inguinal ring is completely closed and the suture material is pulled out (Figure 1F) [4].

Consequence

Takehara et al., [4] reported that in the 711 children they studied, who had 972 internal inguinal hernias, the overall recurrence rate was 0.73% (6 cases) during follow-up ranging from 5 months to 10 years, and no hydroceles or testicular atrophy occurred after surgery. They said that because absorbable materials had been used in 5 cases of the recurrences, the recurrences appeared to have been caused by the absorption of the suture materials without adhesive closure in the hernia sac. Recently, Miyake et al., [5] compared LPEC and open repair (OR) for pediatric inguinal hernia in a total of 2067 patients; 1017of these patients underwent LPEC, and the other 1050 patients underwent OR at a single institution. According to their study, the frequency of postoperative recurrence was similar in the two groups: 0.27% in the LPEC group and 0.52% in the OR group (P=0.72). Other postoperative complications were also similar in the LPEC group and the OR group: testicular atrophy was seen in 0% and 0.29% (P=0.21), iatrogenic cryptorchidism was seen in 0% and 0.29% (P=0.21), and surgical site infection was seen in 0.79% and 0.48% (P=0.54), respectively [5].

CPPV and MCH

The presence of a CPPV in patients with unilateral pediatric inguinal hernia has been a concern for pediatric surgeons. A large review and meta-analysis reported that the incidence of a CPPV detected by laparoscopy with an umbilical approach was approximately 31% [6].Whether the incidence of CPPV changes with age is not yet clear. While some previous studies reported that the incidence of CPPV decreased with age [7,8], Lazar et al., indicated that there was no significant difference in the rates of CPPV by age. Recently Sumida et al. [9] reported the incidence of CPPV revealed by laparoscopy increased as age increased [P < 0.01].

In a study of LPEC for the exploration and treatment of unilateral inguinal hernia in 115 girls, Oue et al., [10] concluded that CPPV that were smaller than 20 mm were unlikely to develop into clinical hernias, so performing a closure procedure for a small CPPV was unnecessary. However, Miyake et al., [5] reported that in their LPEC group, 41.7% were confirmed to have a CPPV and underwent prophylactic LPEC. As a result, MCH was seen in 0.33% in the LPEC group but in 6.48% in the OR group [P < 0.01], indicating that if CPPV was confirmed, prophylactic contralateral LPEC was useful for preventing MCH.Advanced techniques Single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS), also known as laparoendoscopic single-site surgery or single-port access surgery is considered to have the merits of cosmesis and reduced incision pain. Yamato et al., [11] described the first use of single-incision, two-port access for single-incision laparoscopic percutaneous extraperitoneal closure (SILPEC) to manage inguinal hernia in children, in 2011. The point of the procedure was that a 3-mm laparoscope (30-degree heteroscope) was placed within the incision of the umbilicus using an open technique, and grasping forceps (3mm) were inserted through the same skin incision but with a different entry site also using the open technique.

Advanced techniques

Single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS), also known as laparoendoscopic single-site surgery or single-port access surgery is considered to have the merits of cosmesis and reduced incision pain. Yamato et al., [11] described the first use of single-incision, two-port access for single-incision laparoscopic percutaneous extraperitoneal closure (SILPEC) to manage inguinal hernia in children, in 2011. The point of the procedure was that a 3-mm laparoscope (30-degree heteroscope) was placed within the incision of the umbilicus using an open technique, and grasping forceps (3mm) were inserted through the same skin incision but with a different entry site also using the open technique.

A similar technique, percutaneous internal ring suturing (PIRS), was introduced by Patkowski et al., [13] in 2006. PIRS requires only one umbilical port and one needle puncture point. In this technique the suture is placed through the puncture-point access and tied around the hernia sac at the level of the inguinal ring under the peritoneum.

Complication rates and recurrence rates appear to be less for SILPEC than for PIRS. A recent study comparing SILPEC with LPEC for stability and risk of pediatric inguinal hernia was reported by Obata et al., [12]. They stated that there was no significant difference in operating time and that there were fewer total number of postoperative complications in the SILPEC group (37 patients) compared with the LPEC group (72 patients) at a single institution (P = 0.07). They also reported no intraoperative complications or recurrences. For PIRS, complications reported by Patkowski et al., [13] were that incidental puncture of the iliac vein was 2.14%, and postoperative complications including adhesion ileus were 3.77%. The recurrence rate was 2.14%. Przemyslaw et al., [14] reported that the complication of incidental puncture of the iliac vessels was 2.99%, and the recurrence was 1.49%. Thus, SILPEC appears to be a safer technique than PIRS.

Learning curve

Although LPEC is a simple technique, pediatric surgeons need training in how to use the LPEC needle (Lapaherclosure), even if they have performed other kinds of laparoscopic surgery. Yoshizawa et al., [15] reported a retrospective study that assesses the difference in learning curves for the safe performance of LPEC by attending surgeons and residents. Their analysis showed that whereas attending surgeons needed a mean of 12 operations to perform LPEC repairs safety in 30 min or less, residents needed more than 30 operations to safety perform LPEC repairs without supervision.

CONCLUSIONS

In addition to being, simple, safe, effective, and reliable, the LPEC technique has a low recurrence rate equal to that obtained with conventional open repair. Additionally this procedure has advantages of cosmetics, less postoperative pain and the possibility of preventing MCH. Therefore we believe that the LPEC procedure should be viewed as an acceptable alternative to the conventional open repair.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Mimi Zeiger, MA, University of California, San Francisco, for editorial assistance.