Equine Endoparasites: Insights into their Biology, Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Strategies for Treatment and Control

- 1. Fogera District Animal and Fishery Development and Promotion Office, Ethiopia

- 2. Woreta Town Offices of Agriculture and Environmental Protection, Ethiopia

- 3. Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, University of Gondar, Ethiopia

Abstract

Equine endoparasites continue to pose a significant threat to horse health, performance, and productivity worldwide. The most prevalent and pathogenic species—cyathostomins , large Strongyles, Parascaris, Dictyocaulus, Oxyuris, and Gastrophilus—cause a range of clinical and subclinical disorders that impact equine welfare and management. Despite decades of reliance on anthelmintic therapy, the emergence of widespread resistance across multiple drug classes has severely compromised the efficacy of traditional, calendar-based deworming programs. Recent advances in diagnostic technologies, including molecular assays, coproantigen detection, and serological testing, have greatly improved sensitivity and species identification, allowing for more targeted surveillance and treatment. However, the adoption of these tools remains limited by cost, accessibility, and standardization challenges. Sustainable parasite control now emphasizes evidence-based, selective deworming guided by fecal egg counts and resistance monitoring, integrated with sound pasture hygiene, biosecurity, and management practices. Continued research into novel therapeutics, vaccines, and biological control strategies, coupled with stakeholder education and coordinated surveillance, is essential to achieve long-term, sustainable control of equine endoparasites and safeguard the health of equine populations worldwide.

Keywords

• Equine Endoparasites

• Gastrointestinal Nematodes

• Anthelmintic Resistance

• Parascaris Equorum

• Diagnostic Advances

• Integrated Parasite Management

• Equine Health

Citation

Alemayehu H, Alemneh T, Seyoum Z (2026) Equine Endoparasites: Insights into their Biology, Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Strategies for Treatment and Control. J Vet Med Res 13(1): 1291

INTRODUCTION

Horses (Equus ferus caballus), donkeys (Equus africanus asinus), mules, zebras (Equus zebra), and other animals with similar characteristics are classified as “equine” [1]. There are an estimated number of 59 million horses, 43.4 million donkeys and 11 million mules in the world [2]. According to Central Statistical Authority [3] survey report, Ethiopia’s horse, donkey and mule population are estimated to be 2.16 million, 8.4 million and 0.41 million, respectively. Equines, especially in developing countries have a diversified role in the livelihood and health of human being. They are mainly used for pulling carts, public transport, for ploughing, threshing and ambulatory service for sick humans and animals. The recent work done on livelihood contribution of working equines in Ethiopia has disclosed the contribution of these animals in monetary terms [4]. Equines power in both rural and urban transport system is cheap and viable, providing the best alternative in places where the road network is insufficiently developed, and the terrain is rugged and mountainous, and in the cities where narrow streets prevent easy delivery of merchandise [5]. In addition to the transport service they provide, equines have an enormous role as a therapeutic tool for human [6]. Although equines are often described as hardy and resistant animals, they do suffer from a number of health problems [5]. Among which the most common entities leading to ill health, suffering and early demise and finally death are infectious diseases and parasitism, which resulted in considerably reduced animals work output, reproductive performance and most of all their longevity [5-7]. Equines are infected with a variety of parasite species that differ in life cycles, pathogenicity, epidemiology, and the drugs used to combat parasite infections [8]. Infection in these animals can be single or mixed, resulting in a variety of clinical signs. Endoparasites are those parasites that live within the body of the host [5-9], and numerous internal parasites are known to infect equines. These include round worms, flukes, tapeworm, protozoan’s and fly larvae that infest and damage the intestine, respiratory system and other internal organs [10-12]. Anemia, fever, diarrhea, colic, hemorrhage, pale mucosal membranes, jaundice, hyperbilirubinemia, emaciation, and death are some of the diseases that the infective parasites can cause in equines [13-15]. In addition, endoparasites cause damage to the host by inhibiting nourishment, by mechanical obstruction of passage or compression of organs, by blood sucking, by production of toxins with varying effects, by transmitting diseases, and facilitating the entrance of bacteria. All equine species of all ages are affected without age or breed susceptibility [16]; however, the effects of these parasites are greatly evident in young and malnourished equines [17]. Apparently healthy equine can harbor over half a million helminthes parasites [18], and these parasites are a major threat to the health and well-being of equines [17].

The socio-economic impact on livestock productivity and their zoonotic impact on human health are considerably greater and these are mostly due to indirect losses associated with parasitic infections including the reduction in productive potentials such as decreased growth rate and weight loss [19], substantial hazard to the welfare, and mortalities in which they are the leading cause of Equidae deaths [20,21]. Endoparsites could also act as carriers of some microorganisms such as bacteria, protozoans, rickettsia, viruses and fungi and these microbes could cause gastrointestinal infections and diseases [17 22]. Some of these parasites and gastrointestinal infections have been known to be zoonotic and can be transmitted from these infected equines to humans which could lead to mortalities in humans in the long run. Common zoonotic parasitic diseases transmitted from equines to humans include Fasciolosis, Cryptosporidiosis and Giardiasis, which contribute deleteriously to human health [23,24]. Due to the economic significance of parasites, several millions of dollars are spent annually on the control of these parasites worldwide, but these parasites remain a major problem affecting the health and well-being of equines in different parts of the world [22-25]. This review aims to summarize current knowledge on major equine endoparasites, highlighting their biology, epidemiology, pathogenic effects, clinical features, and treatment. It seeks to evaluate recent diagnostic advancements, assess the challenge of anthelmintic resistance, and discuss effective management and control strategies. The paper also aims to identify research gaps and propose future directions for sustainable parasite control in equines.

GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF EQUINE PARASITES

Equines are often subjected to a wide variety of diseases which affect their performance [26,27]. Among these, parasitic diseases stand out as a major challenge to the health and welfare of equines, especially in developing countries. Endoparasites infect equines and have significant impact on the performance of these animals [28]. Helminthes, notably the gastrointestinal parasites, have been recognized as one of the most critical problems of equines in developing countries [29], and infection rates have been estimated to be as high as 90% in equines [30,31]. It has been estimated that over 80% of donkeys in an area can be infected [32,33]. Studies of parasitic infection in equines have uncovered a diversity of helminthes species [34].

Nearly all equines have internal (and of external) parasites, and if left untreated, these parasites can deprive the animal of precious blood nutrients and energy, thereby affecting their performance. Parasites mainly affect the digestive system of equines; however, the respiratory system and other organs may also be affected [35]. The consequences of parasitic infection in equine may range from diarrhea, anemia, fever, colic, weight loss, weak growth, emaciation, impaired growth, increased susceptibility to other infectious diseases and sudden death [29-36].

ENDOPARASITES OF EQUINES

Equines harbor several parasite that prevail in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and other internal organs including round worms (Family: Strongylidae, Spiruridae, Oxyuridae, Trichostrongylidae and Ascarididae), tapeworm (Family: Anopiocephalidae), intestinal and liver fluke (Family: Paramphistomatidae and Fasciolidae), protozoan parasites, and flies (Family: Oestridae) that infest and damage the gastro-intestinal tract and respiratory system depending on the age and natural defense of the individual equine [10-33]. Mixed infections of round worms and tapeworms are also common in equines [1].

Strongyles (red worm) infestation in equines

General description: The red worms (strongyles) are nematode parasites, which are commonly found in the large intestines of horses and other Equidae. They belong to the subfamily Strongylinae (large strongyles) and Cyathostominae (small strongyles). The large strongyles include S. vulgaris, S. edentatus and S. equinus, which, migrate extensively throughout the body, and Triodontophorus species, which do not have a migratory life cycle [5-37]. Members of the genus Triodontophorus (small strongyles) are frequently found in large numbers in the colon and contribute to the deleterious effects of mixed infection with other strongyles [11].

The large strongyles are among the most distractive parasites of equines. All of them are bloodsuckers as an adult worm in the caecum and colon, and their larvae undergo migration that inflicts greater damage especially in foals and yearlings [5-38]. Grossly they are robust dark red worms that are easily seen against the intestinal mucosa. Microscopically species differentiation is based on the size and presence, and shape of the teeth at the base of the buccal capsule [5].

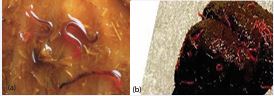

Taxonomy and morphology: Large strongyles are classified under the kingdom animalia, phylum nemathelminthes, class nematoda, order strongylida, superfamily strongyloidae, family strongylidae and subfamily strongylinae. The sex of large strongyles is separate that is female and male. Females are oviparous and eggs are strongyle type. They are reproduced by sexually and they do not have circulatory system (no blood vessel) and respiratory system. Grossly, these parasites look robust dark red worms (Figure 1a), which are easily seen against the intestinal mucosa. They have cylindrical unsegmented shape, body cavity, intestine with anus, nervous system and some has prominent leaf crown surrounding the mouth opening [39].

Figure 1 Adult large strongyles (a) and small strongyles (b) (Source: [40]).

The well-developed buccal capsule of the adult parasite is prominent as the bursa of the male. Microscopically species differentiation is based on size, presence or absence of teeth and the shape of the teeth in the base of buccal capsule. The S. vulgaris has 1.5-2.5 cm long and two ear-shaped rounded teeth; the S. edentatus has 2.5-4.5 cm long, with no teeth; S. equinus has 2.5-5 cm long with three conical teeth and one is situated dorsally and larger than others [41] (Figure 2). The shape of the buccal capsule in each large strongyle species is different from each other those are the S. vulgaris has oval shaped buccal capsule, the S. edentatus has normal buccal capsule and the S. equinus has oval in outline buccal capsule [39].

Figure 2 Anterior end of large strongyles depicting the buccal capsule, leaf crown and tooth-like structures at the base of the buccal capsule (Source: [40]).

Epidemiology: Large strongyles are a common parasite of horse throughout the world and causes deaths when control measures are neglected. In area with cold winters and mild summer, egg deposition peaks in spring and remains high over summer. At this time, temperate is suitable for larval development and massive contamination of pasture. Infective larvae may occur in the summer and early autumn, when young susceptible horses are present. If the summer is hot and dry, only a small proportion of strongyle eggs develop to larvae and these may be short lived, but continual re-infection keeps pasture contamination high [42]. In Ethiopian, S. vulgaris is very common and highest in equids in mid and high altitude areas where the rainfall is relatively high and follows as a bimodal pattern [41].3

Age is important in regard to susceptibility to infection and disease and foals and yearlings are usually the most affected while adults over five years of age usually harbor more moderate numbers of worms. Any factors that reduce immunity in adult horses are also likely to increase their strongyle burdens: for example, dietary problems and over workload [43]. Higher egg numbers per gram are recorded in young horse (= 3 year) as compared with older horse. The excretion of eggs is not affected by the sex of the animals [44].

The main sources of parasites are horses infected with adult worms. Young animals of less than 4-5 years are usually the most heavily infected and, because of their greater susceptibility, adult female worms in the intestine of these animals are fairly prolific and excrete considerable numbers of egg in the feces. Adult horses tend to have lower parasite burdens because of the development of immunity; however, this resistance or immunity is incomplete, so the animals continue to pass low number of eggs in their feces, these contributing to significant contamination of pasture [43]. Strongylosis may occur in adult animals kept in sub urban paddocks and subjects to overcrowding and poor management [41].

Life cycle: All species of equine strongyles have direct life cycles [45] (Figure 3). Eggs are laid by adult female worms and passed in the faeces to the external environment where they hatch to the first stage larvae (L1) at 260C which grows and molts to L2 and then to the L3 (infective stage) requiring approximately ten days to two weeks [46]. Five developmental stages are recognized in the life cycle of these parasites: first larval stage (L1), second larval stage (L2), third larval stage (L3), fourth larval stage (L4) and fifth larval stage (L5) [41]. Sheathed L3 is the only larval stage that can infect a new host, therefore called the infective larva. Infection of host occurs by ingestion of (L3), then they pass to the small intestine, remove outer sheath and initiate the further development. Exsheathment in the host gut is stimulated by certain physiological / biochemical conditions [47]. This triggers the larvae to release its exsheathing fluid hence disintegrating the larval sheath, thereby releasing the larvae either through an anterior cap (as in large strongyles) or via a longitudinal split in oesophageal region (in small strongyles) [48]. At this point, the life cycle of the various strongyles begin to differ. After ingestion of infective larvae (L3) through contaminated feed and water, the L3 travel through digestive system to large intestine and thereafter, those of S. vulgaris migrate towards anterior mesenteric artery and its branches (Figure 3); S. edentatus to liver or flank region and S. equinus to the liver and pancreas. The larvae come back into the lumen of caecum and colon and attain maturity. The pre-patent period in S. vulgaris is 6-7 months, S. edentatus is 10-12 months, and S. equinus is 8-9 months [46]. Large and small strongyle larvae have different migratory patterns. While large strongyles larvae have a preference for extra-alimentary tissues [49], the small strongyles larvae have an affinity to reside inside the fibrous cysts in sub-mucosal lining of the caecum and ventral colon [46-50].

Figure 3 The Life cycle of Strongyles (Strongylus vulgaris) (Source: [40]).

Pathogenesis: The disease process associated with the strongyle can be divided into those producing by migrating larvae and those producing by adult worms. Heavy intestinal infection can alter intestinal motility, permeability and absorption [41]. Naturally infected horses usually carry a mixed load of large and small strongyles in the intestine [46]. Among the large strongyles, S. vulgaris is usually the cause of the most devastating internal parasitic disease. The migrating larvae of S. vulgaris are more harmful as they migrate towards cranial mesenteric artery and its branches and lead to the formation of thrombus, which results in interference of blood flow to the intestinal wall and can cause gangrenous enteritis; intestinal stasis, intussusception; and possibly rupture. The thrombi detached, may block vital arteries like iliac artery, and a temporary lameness may occur. The verminous aneurysms in the cranial mesenteric artery and its branches may cause colic by exerting pressure on the associated nerve plexus. Hematological and biochemical studies performed in equines infected with S. vulgaris infection showed a decrease in haemoglobin rates, total serum proteins and an increase in lymphocytic count. The larvae of S. equinus may produce haemorrhagic tracts in the liver and pancreas. The larvae of S. edentatus may cause haemorrhagic nodules in the wall of peritoneum, caecum and colon. Adult large strongyles have large buccal capsules and are active blood feeders; they attach themselves, feed on mucosal plugs in the large intestine, suck blood producing anemia of a normochromic and normocytic type. S. edentatus and S. equinus adults are more harmful to the horse and suck more blood than S. vulgaris adults, but the larvae are not as dangerous [41-46].

Clinical signs: In natural infestations, it is often impossible to quantify the effect of individual strongyle species as a clinical picture usually represents the combined effects of a mixed infestation. Unthrifitness, poor hair coat, anemia (if there is significant blood loss), impaired performance, poor appetite, depression, intestinal rapture, weight loss, diarrhea and death are signs associated with a wormy horse [41]. The principal clinical signs of a large strongyle (primarily S. vulgaris) infection are directly associated with the migrating larval stages in the walls of cranial mesenteric arteries and its branches, cause interference in blood flow to the intestinal wall, leads to the formation of thrombosis. These thrombi are responsible for arterial blockade which at the time of necropsy is evidenced by infarction of intestinal walls. The infected horses develop clinical signs like pyrexia, anorexia and severe colic [41]. “Verminous aneurysm” or “worm aneurysm” is classic of this parasite [42].

The significance of migrating larvae of S. vulgaris in natural cases of colic is difficult to assess but it is generally recognized that where strongyle infection of horses are efficiently control the incidence of colic is markedly decrease. The frequency of colic is directly related to the parasite control program. More colic in untreated young horses will mean more in the adults. Horses will have intermittent diarrhea and lameness from emboli in the legs may appear during exercise and disappear with rest [41]. The cyathostomins infections are generally mild with symptoms like anorexia, weight loss, poor hair coat, digestive disturbances, lethargy, emaciation, oedema and decreased intestinal motility [46,47].

Diagnosis: Diagnosis is based primarily on the basis of grazing history, clinical signs, faecal sample examination by faecal floatation technique for detection of strongyle egg and per rectal examination reveals aneurysm of cranial mesenteric artery [46]. Although oval, thin shelled strongyle eggs on fecal examination may be a useful aid to diagnosis, it is important to remember that substantial worm burdens may be associated with fecal egg counts of only a few hundred EPG due to either low fecundity of adult worms or to the presence of many immature parasites [41]. Diagnosis of the large strongyle infections can be assumed if eggs are found in the feces. However, because of the prolonged pre-patent period of all species in this group, eggs will not be present in the feces in animals less than 9-12 months old [41].

Nevertheless, regarding strongylosis, diagnosis by faecal microscopy in terms of morphology of the strongyle eggs does not allow the species differentiation, especially in cases of mixed infections, which are common and frequent in field conditions, not even to the sub-family level [51]. For this reason, coproculture for larval cultivation is the most practical and readily available method to differentiate between large and small strongyles, based on the morphology of the L3 stage [52,53]. In general, a specific diagnosis is difficult to achieve in every case, and only few clinical observations or laboratory results are pathognomonic for the disease syndrome associated with strongyle infection [42].

Treatment: Treatment may be targeted against immature and adult large strongyle worms in the lumen of the intestine, against migrating strongyle larvae, particularly S. vulgaris [42]. The most commonly used method for controlling GI parasites is the application of anthelminthic drugs [54]. Thiabendazole, a benzimidazole group member, has been widely used and several other anthelminthic drugs have been approved for use in equine, including tetrahydropyrimidines and organic phosphorus compounds [55].

In current scenario, mainly three broad spectrum group of anthelminthic are used, categorized by their mechanism of action: pro-benzimidazole/benzimidazoles (e.g. Febantel, Netobimin, Thiabendazole, Cambendazole, Fenbendazole and Oxibendazole) imidazothiazoles/ tetrahydropyrimidines (e.g. Levamisole, Tetramisole, Pyrantel and Morantel) and the macrocyclic lactones (e.g. Avermectins and Milbemycin [46-56]. Equines are usually treated with these anthelmintic drugs to eliminate adult strongyles from the large intestines to prevent excessive contamination of pastures with eggs and L3. However, some deworming treatments are less effective because the encysted larvae remain protected within a barrier wall for up to two and a half years [41].

Prevention and control: The approach of most equine strongyle control programs goes into the category of prevention of pasture contamination that is prevention of excessive pasture contamination thereby minimizing the risk of exposure to infective larvae [41-57]. The mixed or alternative grazing with ruminants can reduce pasture infectivity as horse strongyles will not establish in these hosts. Removal of all horse feces from the fields twice weekly is highly effective for the control of strongyles [42]. Since horse of any age can be become infected on the excreted eggs, all grazing animals over two months of age should be treated every 4-8 weeks with effective broad spectrum anthelmintics. Any new animals joining a treated group must receive anthelmintic and be isolated for 48-72 hours before being introduced [41]. Key elements of an effective control program include strategic treatment and improve pasture management [41]. Regular treatments of all animals in any group of horses, starting from the weaners are typically used to eliminate adult strongyles and these prevent excessive contamination of pasture with eggs and infective larvae (L3). The rotation of dewormers has been suggested as a means of helping prevent parasites’ developing resistance medications. The separation of different age group at grazing is recommended for the eradication of Strongylosis. The goal of strongyle control plan is to keep the number of adult, egg-bearing strongyles at low subclinical levels through the strategic use of selected, approved anthelmintics and programs that limit the horse’s exposure to infected manure [43].

Ascariosis

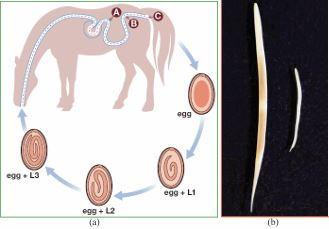

Etiology: Ascariosis in equines is exclusively caused by Parascaris equorum. It is a very large whitish nematode, up to 40 cm in length, cannot be confused with any other intestinal parasites of equines [5] (Figure 4b).

A: Hatching of third stage larvae (L3) in the stomach and small intestine, penetration of intestinal veins. B: Larvae reach liver via portal vein, migration through liver tissue and penetration of liver veins. C: Larvae reach lung via vena cava and right heart, penetration into lung alveoles and migraton via trachea and pharynx to small intestine (moulting to L4 and St5 prior to development into adults).

Figure 4 The life cycle of Parascaris equorum (a), and Adults in the small intestine (b) (Source: [40]).

Biology and epidemiology: Measuring up to 50 cm in length at the adult stage, these worms which reside in the small intestine represent one of the largest known parasitic nematode species. The females can shed hundreds of thousands of eggs per day (up to 200,000 eggs per day), thus contributing to considerable environmental contamination [58]. The infective stage is the third stage larva (L3) within the egg, which can survive in the environment for several years, even under harsh conditions such as prolonged periods of frost. Consequently, both stables and pastures once contaminated will remain a constant source of infection [40]. Typical Parascaris egg has a thick shell containing a single cell inside [5] (Figure 4a). The eggs are very resistant to adverse conditions, like drying or freezing and the larvae rarely hatch and infection usually takes place through ingestion of the eggs [5]. For this reason, no significant difference was observed in the infection prevalence of ascariosis between dry and wet season [59]. The infection is common throughout the world and is the major cause of unthriftiness in young foals [5]. Adult worms are common in young equids and infrequent in adults [11]. However, the high prevalence of P. equorum in an adult may be observed irrespective of the age of equines if the animals cannot develop immunity as a young or they might have been immuno-compromised as adults [33].

Life cycle: Following ingestion of eggs, larvae are released and penetrate the small intestinal wall to begin a somatic migration via the bloodstream through the liver, heart and lungs [58]. There, the larvae transfer to the respiratory system where they are transported with the mucosal flow to the larynx and, after being swallowed, reach the small intestine approximately three weeks post infection [60]. It then takes at least another 7 weeks of maturation before the first shedding of eggs in the faeces (pre-patent period 10-16 weeks) [40-58] (Figure 4a).

Clinical signs: Often, no clinical signs are observed. Sometimes during the somatic migration, clinical signs occur mostly associated with pathological changes in the lungs, whereas the migration through the liver does not appear to cause clinical signs. In the lungs, changes include hemorrhagic mucosal lesions and heavy infections can result in coughing and decreased weight gain in young stock and can also lead to secondary bacterial or viral infections [40]. Parascaris equorum can definitely be pathogenic in foals. It can produce ill health but also can kill foals by affecting the small intestine by impaction and rupture of the wall, resulting in peritonitis [61]. During the intestinal phase (Figure 5), Parascaris spp. infected animals show reduced appetite and a rough coat; intermittent colic and wasting may also occur [40]. Occasionally, heavy infections can result in severe colic, respiratory signs (from migrating larvae), ill thrift, diarrhea, perforation, invagination followed by peritonitis, and intestinal obstruction that may be fatal [11]. Under current epidemiological conditions in most western European countries, the infection intensity is low and the vast majority of cases in foals and young horses are subclinical. Adult mares can occasionally excrete eggs and so act as a source of infection for subsequent generations [40].

Hatching of L3 in the small intestine (A), histotrophic phase in the caecum and colon (B), adults develop in the colon, females emerge from the anus to lay egg clusters on the perineum (C)

Figure 5 The life cycle of Oxyuris equi (a); and Adult female & male worms (b) (Source: [40]).

Treatment: Foal ascariosis control programs are based on year round monthly rotational anthelmintic treatment with benzimidazole (e.g. fenbendazole, tetrahydropyrimidine (e.g. pyrantel) and macrocyclic lactones (e.g. ivermectin and moxidectin) [62]. In Parascaris spp., anthelmintic resistance to macrocyclic lactones, probably due to intensive use of these drugs, has been widely reported since 2002 [63]. Additionally, recent reports have suggested anthelmintic resistance to pyrantel salts and benzimidazole drugs to be present as well [64,65]. In Italy, for instance, anthelmintic resistance to pyrantel and ivermectin in ascarids in horses has been reported since 2009 [58-66].

Diagnosis, prevention and control: Diagnosis of Parascaris spp. infections relies on the direct detection of eggs (round, brownish, approximately 100 μm in length, thick-shelled) by faecal flotation and/or of pre-adult stages or adult worms in the faeces. Coproscopic analysis is based upon the microscopic detection of the eggs either during a qualitative or quantitative flotation protocol [40]. Sustainable control approaches should include regular faecal monitoring (preferably individual samples). Stable and pasture hygiene must accompany anthelmintic treatment, which should begin at two months of age and repeated every three months during the first year of life, employing different drug classes [40-61].

Gasterophilus species (Bot flies)

Etiology: Species of Gasterophilus, known as bots, are obligate parasites of horses, donkeys, mules, zebras, elephants and rhinoceroses [5]. Bot flies are arthropods of the genus Gasterophilus (Diptera: Oestridae) [67]. Gasterophilus intestinalis, G. haemorrhoidalis, G. nasalis,

G. inermis and G. pecorum are the most prevalent species. Gasterophilus intestinalis, G. haemorrhoidalis and G. nasalis frequently infest grazing horses; G. inermis and G. pecorum are found less often. Their larvae mainly cause gastrointestinal myiasis [40].

Biology and epidemiology: Adult flies resemble honey bees and females play the major role in the infection. In southern Europe they may already be active in spring/ early summer, while in temperate regions, egg laying takes place in late summer [68]. Females of most Gasterophilus species fly near horses and dart very rapidly close to the skin to attach an egg to a hair. This fly activity produces a special buzzing noise which many horses find very disturbing. Females die after laying small (1-2 mm), mostly operculate and yellowish, eggs. The eggs can be seen fairly easily with the naked eye, especially on animals with a dark hair coat [40]. Regarding the egg localization, G. intestinalis places eggs on the hair of the forelimbs, shoulders and flanks while most other species deposit their eggs on the head. G. pecorum is an exception as females lay eggs in the environment. Humans have occasionally been infected showing conspicuous tracks in the cheeks, and even infection of the digestive tract [40].

Life cycle: The hatching of first stage larvae (L1) takes place after a mechanical stimulus (G. intestinalis and G. pecorum) or spontaneously (G. nasalis). The L1 reach the oral cavity through oral uptake (licking or grazing for G. intestinalis and G. pecorum respectively) or by larval migration. Second stage larvae (L2) are found in the stomach and duodenum where they moult into third stage larvae (L3). The L3 measure 16-20 mm in length, have a barrel-shaped form and bear two large mouth hooks. The segments have one or two rows of spines. After several months, the L3 finally leave the host in the faeces and pupate in the soil, before the adult flies emerge into the environment. The parasitic phase takes 8-10 months and the pupal phase 3-8 weeks [67]. The adults mostly emerge during June/July and are usually active until October or November, although their activity may begin earlier and last longer in southern European regions [40].

Pathogenesis and clinical signs: Gasterophilus L2/ L3 are found attached to the mucosa of the stomach (G. intestinalis), duodenum (G. nasalis, G. haemorrhoidalis) or rectum (G. haemorrhoidalis, G. inermis), where they may cause focal, superficial mucosal ulceration, cutting and piercing of tissues to facilitate feeding [68]. When L1 are found in the oral cavity, they migrate through the mucous membranes of the tongue, gums and palate, causing gingivitis and pain which may affect food intake [40]. Generally, the first clinical signs of gasterophilosis are characterized by difficulties in swallowing due to the localization of the larval stages in the throat. Remarkably, massive infections with Gasterophilus spp. are not always associated with clinical signs and are thus considered much less pathogenic than most nematode parasites [67]. Nevertheless, gastric and intestinal ulcerations have been associated with this infection, as well as chronic gastritis, gut obstructions, volvulus, rectal prolapses, rupture of the gastrointestinal tract, peritonitis, anemia and diarrhea [40].

Diagnosis: The presence of Gasterophilus spp. can be confirmed in the summer/autumn by inspecting the horse’s coat and finding yellowish eggs attached to the hair. Gastrointestinal examination through endoscopy may allow the detection of Gasterophilus spp. larvae attached to the stomach and duodenum. ELISA based on excretory/ secretory antigens of G. intestinalis L2 for antibody detection and PCR techniques have been used; however, these tools are not yet considered routine laboratory techniques [40].

Treatment, prevention and control: The larval stages of Gasterophilus are highly susceptible to macrocyclic lactones (particularly Ivermectin) and will be eliminated during regular deworming with these drugs. As fly activity ceases with the first frosts, an appropriate treatment in late autumn, e.g. early November, should remove all larvae present within horses [40-67]. The removal of the eggs by hand with a special bot comb or bot knife or thoroughly washing the hair with warm water mixed with an insecticide is recommended though it is usually not sufficient to effectively prevent gastrointestinal infection [41]. Thus, controlling of insects and its larval stages required natural alternative methods without harming the environment. Nowadays, the plant extracts e.g. Neem seed oil is a new protocol study for controlling the disease as well as the parasite and pests [69-71].

Pinworm (Oxyuris equi)

Biology and life cycle: Oxyuris equi, the equine pinworm, is classified in the superfamily Oxyuroidea. Oxyuroid nematodes inhabit the distal alimentary tract of mammals and reptiles, and female worms generally deposit their eggs outside the host. In addition to equines, oxyuroid species are found among domestic animals only in sheep and goats (Skrjabinema spp.) and in several species of laboratory animals. Human individuals also host a common oxyuroid (Enterobius vermicularis) and multiple other species infect various New and Old World primates [72].

Oxyuris equi is a fairly large nematode (~1-6 cm in length) that resides as an adult in the small colon and dorsal colon of equids [73]. Oxyuris is known as a pinworm because the tail end of the female is sharply pointed [74] (Figure 5b). Pinworms (Oxyuris equi) are an annoying but not life threatening parasite of equines. They provoke irritation of the perianal region of equines causing them to rub and bite their tail. This can result in hair loss and sometimes physical damage to the tissue of the area. The parasite is ubiquitous but of greater prevalence in areas of high rainfall [5].

The mature females are large grayish-white, opaque worms, with a very long tapering tail that may reach 10 to 15cm in length, whereas the mature males are generally less than 1.2 cm long (Figure 5b). The L4 stages of this parasite are 5 to 10 mm in length, having tapering tails and are often attached orally to the intestinal mucosa. Egg of O. equi is ovoid, yellowish, thick shelled and slightly flattened on one side with a mucoid plug at one end. Eggs contain a morula or larval stage when shedding in faeces [5-11] (Figure 5a).

(a) = itching and dermatitis of the tail root; (b) = massive O. equi egg excretion with cream-colored, dried egg clusters.

Figure 6 Oxyuris equi infection in horse (Source: [40]).

Clinical signs: Pinworms are the most frequent nematodes that affect horses of all ages and the infection is more common in stabled horses than in those at pasture because the eggs are poorly resistant in external conditions [73]. Oxyuris equi infections arise in stables and may also occur on pasture, but usually only a few horses appear to be clinically affected. Oxyuris equi is rarely considered a major

Treatment, prevention and control : The macrocyclic lactones (MLs) and benzimidazoles (BZs) are effective against pinworms and their larval stages. Pyrantel has variable efficacy against pinworms. Recent anecdotal reports on the reduced efficacy of MLs (ivermectin and moxidectin) against O. equi must be viewed as potential resistance. The perianal region of infected horses should be washed with hot water containing a mild disinfectant to relieve the pruritus and to prevent the spread of pinworm eggs throughout the horse’s environment [40-72].

Threadworm (Strongyloides westeri)

Biology: The nematode Strongyloides (Strongyloides westeri) resides in the small intestine, mainly the duodenum [75]. Patent infections are largely found in young horses, i.e. foals up to six months old. Occasionally, older horses can harbour this parasite and mares are an important source of infection for their foals. It is a unique parasite, since it only develops female and no male parasitic stages. The very slender, small (maximum length 10 mm) parasitic females reproduce through parthenogenesis, that is, development from an unfertilized egg. They shed small, thin-shelled, embryonated eggs (40-50 x 30-40 μm) containing the first stage larvae (L1) which hatch in the environment. These can develop directly to infective third stage larvae (L3) or give rise to free-living males and females that will reproduce and in turn produce infective (L3) [5-61].

Transmission and life cycle: Infection may occur by ingestion of L3 in the mare’s milk (“lactogenic infection”) and this is the primary mode of transmission of S. westeri to foals. Later on, transmission also occurs by ingestion of infective L3 from the pasture or environment, or through percutaneous infection. When percutaneous infection occurs in immune adult horses, S. westeri larvae do not become established in the alimentary tract and patent infections are rare. Instead, they are distributed through various somatic tissues where they may remain viable for long periods, probably years [40]. In mares, the hormonal shifts during pregnancy and lactation probably stimulate these larvae to resume migration to the mammary glands so that they are transmitted to the foal. After being ingested with the milk, the larvae undergo a somatic migration starting with the penetration of the small intestinal wall [75]. They subsequently travel through the lungs, via the trachea and pharynx where they are swallowed finally reaching the small intestine. Here they mature to adult female worms. The prepatent period can take some weeks but can be as short as 5-8 days [11].

Pathogenesis and clinical signs: During massive percutaneous infection, local dermatitis can occur. The hair coat may become dull and animals can be stressed by local skin irritation and itching, which is often a consequence of an allergic response to re-infections [75]. The major pathogenic effect of infection occurs in the intestine, where adult females embed in the small intestinal mucosa and cause local enteritis, which can lead to diarrhea [40-75]. The role of S. westeri as the cause of diarrhea in young foals is unclear since there are reports of high faecal egg counts associated with severe cases of diarrhoea while high Strongyloides egg shedding has also been found in animals showing no clinical signs. Clinically affected foals may become anorexic and lethargic but in situations where regular worm control is employed, it appears that most S. westeri infections are asymptomatic. It should be noted that there are many cases of diarrhea in foals aged 1-2 weeks which are not associated with S. westeri infection [40-75].

Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention and control:

Diagnosis of S. westeri infection is performed by coproscopic detection of the typical eggs in faeces [40]. Treatment and control of S. westeri infections should involve both anthelmintics and basic hygiene measures. Under the current epidemiological situation, the formerly often-employed, routine treatment of foals during the first few weeks of life does not seem justified anymore due to the low prevalence and lack of evidence for S. westeri associated disease in foals [40]. On farms where S. westeri has previously been detected, regular deworming of mares, before or shortly after parturition (i.e. 1-2 days) is thought to reduce the number of larvae in milk and lower the incidence of diarrhoea in foals [40]. For clinical cases, a number of drugs are available including Ivermectin or Fenbendazole, the latter at a dosage of 50 mg/kg body weight (significantly higher than the standard dosage of 7.5 mg/kg body weight). Pasture and stable hygiene, together with cleaning of the mare’s udder should reduce the risk of environmental contamination and foal infection [40].

Lungworm (Dictyocaulus arn????ieldi)

Biology: Dictyocaulus arnfieldi is the true lungworm affecting donkeys, horses, mules and zebras and is found throughout the world [76,77]. It is a relatively well adopted parasite of donkeys but tend to be quite pathogenic in horses, where this parasite is endemic [38-78].

The equine lungworm, D. arnfieldi, is a nematode which occurs most commonly in the donkey, and the donkey is considered to be the more normal host. Patent infections may persist in donkeys throughout their lives. Although less common, patent infections can also be found in mules and horses, particularly in foals and yearlings. Donkeys, therefore, provide the most important sources of pasture contamination, nevertheless, a small proportion of infected adult horses shed low numbers of eggs and this may be sufficient to perpetuate the lifecycle even in the absence of donkeys and foals [37]. Cross transmission may occur when these different hosts share the same pasture [40].?

Epidemiology: The epidemiology of D. arnfieldi, is characterized by its distinct host preferences and transmission dynamics. Donkeys (Equus asinus), are the natural and primary reservoir hosts, often exhibiting patent (egg-shedding) infections with minimal clinical signs, while horses (Equus caballus), are aberrant hosts, rarely developing patent infections but suffering more severe respiratory pathology, including chronic coughing and bronchitis when exposed [79]. The parasite has a direct life cycle: infective third-stage larvae (L3) develop on pasture from feces-contaminated environments, typically within 5-7 days under warm, moist conditions,and are ingested during grazing [79]. Transmission is heavily influenced by shared pasture use between donkeys and horses, with donkeys acting as the main source of environmental contamination due to their high prevalence rates (e.g., 54% in Kentucky, USA, and 31.8% in Urmia, Iran) [79,80]. Foals and immunologically naïve adult horses are particularly susceptible, and outbreaks are linked to management practices such as co-grazing or inadequate anthelmintic use [81]. Geographic distribution is global, with reported cases in temperate and tropical regions, including North America, Europe, Africa, and Asia, though prevalence varies locally due to climate, pasture management, and donkey population density [79-82].

Predilection site and life cycle: The detailed life cycle is not fully known, but is considered to be similar to that of bovine lungworm, Dictyocaulus viviparous [78]. Adult

D. arnfieldi can measure up to 6 cm in length and can be found in the bronchial tree, especially in the terminal bronchioles. Adult females are ovoviviparous and lay eggs containing first-stage larvae (L1) in the bronchial secretions which are transported with the mucus to the pharynx, swallowed and passed in the faeces. The eggs hatch almost immediately to release L1 which moult twice to produce third stage infective larvae (L3). Infection occurs by ingestion of L3 with herbage. Following ingestion of L3, the larvae penetrate the small intestinal wall and migrate via the lymph and blood vessels to the heart and lungs. There they penetrate the alveoli and develop into adult stages in the bronchial tree. The prepatent period is about 3 months [40-83].

Clinical signs: The most common finding in the majority of clinical cases of lungworms in horses is a history of previous direct or indirect contact with donkeys. Major significant lesions are those of chronic eosinophilic bronchitis and bronchopneumonia [40]. Clinically, chronic coughing is the most frequent sign; occasionally there may be a mucopurulent bilateral nasal discharge, dyspnoea, tachypnoea and weight loss. The clinical disease is more severe in young horses (yearlings) [78]. However, pony foals may be infected and shed L1 in the faeces while showing no clinical signs. Infected donkeys rarely show any signs of infection despite the presence of adult worms in the lungs [84]. Comparatively, mild clinical signs like hyperpnoea and harsh respiratory sounds can be associated with some infections; however, there are a few reports of severe outbreaks of disease in adult animals which have resulted in fatalities, even in donkeys [40].

Diagnosis: Diagnosis is mainly based on grazing history and clinical signs, since in horses, lungworm infections rarely develop to patency. Confirmation of a patent infection can be achieved by the demonstration of embryonated eggs or free L1 of D. arnfieldi (420-480 μm length) isolated by flotation technique in combination with the Baermann method. In some cases, broncho- alveolar lavage has proved successful in the recovery of eggs/L1 and L4/L5 of D. arnfieldi from the nasal and upper respiratory tract. A positive clinical response to appropriate anthelmintic treatment in suspected cases may be an indicator that lungworm infection was indeed present [40-78].

Treatment, prevention and control: In general, equine lungworm infections are well controlled on farms with good parasite control measures in place. However, when respiratory signs including coughing are associated with a poor response to antibiotics, a parasitic pneumonia should be considered as a possible diagnosis, especially if donkeys are or were present on the farm [40]. This is particularly true when the anthelmintic control program is infrequent and when there is a history of horses and donkeys grazing on the same pasture. Generally, control of equine lungworm infection will be achieved by following the general control measures for parasitic diseases in horses. The MLs and BZ anthelmintics are effective against this parasite [40-78]. It is likely that control program for large and small strongyles which use these compounds and are applied strategically during the course of the year will also be effective in the control of D. arnfieldi infections [78].

CONCLUSIONS

Equine endoparasitism remains a persistent and complex challenge in modern horse management, with species such as Strongyles, Parascaris, Dictyocaulus, Oxyuris, and Gastrophilus continuing to exert significant health and economic impacts worldwide. Despite decades of control efforts, the widespread development of anthelmintic resistance has diminished the effectiveness of traditional, routine deworming programs, emphasizing the urgent need for more sustainable approaches. Advances in diagnostic technologies—including molecular assays, coproantigen detection, and serological tests—have greatly enhanced the accuracy and sensitivity of parasite identification, enabling early diagnosis and improved monitoring of treatment efficacy. However, practical limitations related to cost, accessibility, and standardization continues to hinder their routine application in field conditions. Effective parasite management now requires an integrated approach that combines diagnostic-led, targeted deworming with sound pasture management, manure control, and biosecurity measures. Selective treatment strategies guided by fecal egg counts and resistance monitoring not only reduce selection pressure on drugs but also help maintain refugia and delay further resistance development. Furthermore, continued research into novel anthelmintics, vaccine development, and biological control options is vital to broaden available control tools. In conclusion, the sustainable control of equine endoparasites depends on the harmonization of advanced diagnostics, responsible anthelmintic use, and effective management practices. Collaboration among veterinarians, researchers, and horse owners, supported by education and surveillance, is essential to preserve drug efficacy, enhance equine health, and ensure the long-term stability of parasite control programs worldwide.

REFERENCES

- Alali F, Jawad M, Al-Obaidi QT. A review of endo- and ecto-parasites of equids in Iraq. J Advances in VetBio Science and Techniques. 2022; 7: 114-128.

- Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). Food and Agriculture Organization Stat Database. 2011.

- Central Statistical Authority (CSA). Agricultural samples survey volume II. Statistical Bulletin 585. Addis Ababa. 2017.

- Berhanu A, Yoseph S. The Brooke: Donkey, Horses and mules their contribution to peoples livelihoods in Ethiopia. 2011.

- Gebresilassie DB, Andarge B. Review on the epidemiological features of equine Endoparasites in Ethiopia. J. Parasitol. Vector Biol. 2018; 10: 97-106.

- Schultz PN, Remick-Barlow GA, Robbins L. Equine-assisted psychotherapy: a mental health promotion/intervention modality for children who have experienced intra-family violence. Health Soc Care Community. 2007; 15: 265-271.

- Tamador EEA, Ahmed AI, Abdalla MI. The Role of Donkeys in Income Generation and the Impact of Endoparasites on Their Performance. J Vet Med Animal Production. 2011; 2: 65-89.

- Scoles GA, Ueti MW. Vector ecology of equine piroplasmosis. AnnuRev Entomol. 2015; 60: 561-580.

- Heinemann B. Veterinary parasitology. The practical veterinarian.United State of America. 2001: 53.

- Pereira JR, Vianna SS. Gastrointestinal parasitic worms in equines in the Paraíba Valley, State of São Paulo, Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2006; 140: 289-295.

- Taylor MA, Coop RL, Waller L. Veterinary Parasitology 3rd Ed. Oxford, England: Blackwell Science, Ltd. 2007.

- Alemayehu R, Etaferahu Y. Gastrointestinal Parasites of Equine in South Wollo Zone, North Eastern Ethiopia. Global Veterinaria. 2013; 11: 824-830.

- Raue K, Heuer L, Böhm C, Wolken S, Epe C, Strube C. 10-year parasitological examination results (2003 to 2012) of faecal samples from horses, ruminants, pigs, dogs, cats, rabbits and hedgehogs. Parasitol Res. 2017; 116: 3315-3330.

- Camino E, Dorrego A, Carvajal KA, Buendia-Andres A, de Juan L, Dominguez L, et al. Serological, molecular and hematological diagnosis in horses with clinical suspicion of equine piroplasmosis: Pooling strengths. Vet Parasitol. 2019; 275: 108928.

- Zhao S, Wang H, Zhang S, Xie S, Li H, Zhang X, et al. First report ofgenetic diversity and risk factor analysis of equine piroplasm infection in equids in Jilin, China. Parasit Vectors. 2020; 13: 459.

- Aftab F, Khan MS, Perez K, Avasi M, Khan JA. Prevalence and Chemotherapy of Ecto-and Endoparasites in Rangers Horses at Lahore–Pakistan. Int J Agri Biol. 2005; 7: 853-854.

- Belay W, Teshome D, Abiye A. Study on the prevalence of gastrointestinal helminthes infections in equines in and around Kombolcha. J Vet Sci Technol. 2016; 7: 367-372.

- Matthee S, Krecek RC, Milne SA. Prevalence and biodiversity of helminth parasites in donkeys from South Africa. J Parasitol. 2000; 86: 756-762.

- Dogo GIA, Arinze SC, Oshadu DO. Incidence of gastrointestinal parasites in Zebu and N’dama Breeds from Cattle Ranches in Jos Plateau, Nigeria. J Parasite Res. 2020; 1: 2690-6759.

- Alemayehu MT, Abebe BK, Haile SM. Investigation of Strongyle Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors in Horses in and around Alage District, Ethiopia. J Parasitol Res. 2022; 2022: 3935008.

- Mathewos M, Teshome D, Fesseha H. Study on Gastrointestinal Nematodes of Equines in and around Bekoji, South Eastern Ethiopia. J Parasitol Res. 2022; 2022: 8210160.

- Ogbeina KE, Dogob GA, Oshadub DO, Edehc ER. Gastrointestinal parasites of horses and their socio-economic impact in Jos Plateau – Nigeria. Appl. Vet. Res. 2022; 1: 1-11.

- Zahedi A, Paparini A, Jian F, Robertson I, Ryan U. Public health significance of zoonotic Cryptosporidium species in wildlife: Critical insights into better drinking water management. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2015; 5: 88-109.

- Sazmand A, Bahari A, Papi S, Otranto D. Parasitic diseases of equids in Iran (1931-2020): a literature review. Parasit Vectors. 2020; 13: 586.

- Lem MF, Vincent KP, Pone JW, Joseph T. Prevalence and intensity of gastro-intestinal helminths in horses in the Sudano-Guinean climatic zone of Cameroon. Trop Parasitol. 2012; 2: 45-48.

- Khamesipour F, Dida GO, Anyona DN, Razavi SM, Rakhshandehroo E. Tick-borne zoonoses in the Order Rickettsiales and Legionellales in Iran: A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018; 12: e0006722.

- Moazeni M, Khamesipour F, Anyona DN, Dida GO. Epidemiology of taeniosis, cysticercosis and trichinellosis in Iran: A systematic review. Zoonoses Public Health. 2019; 66: 140-154.

- Pritchard JC, Lindberg AC, Main DC, Whay HR. Assessment of the welfare of working horses, mules and donkeys, using health and behaviour parameters. Prev Vet Med. 2005; 69: 265-283.

- Khamesipour F, Taktaz-Hafshejani T, Tebit KE, Razavi SM, Hosseini SR. Prevalence of endo- and ecto-parasites of equines in Iran: A systematic review. Vet Med Sci. 2021; 7: 25-34.

- Fikru R, Reta D, Teshale S, Bizunesh M. Prevalence of equine gastrointestinal parasites in western highlands of Oromia, Ethiopia. Bulletin of Animal Health and Production in Africa. 2005; 53: 161-166.

- Valdez-Cruz MP, Hernandez-Gil M, Galindo-Rodriguez L, Alonso- Diza MA. Gastrointestinal parasite burden, body condition and haematological values in equines in the humid tropical areas of Mexico. In R. A. Pearson, C. J. Muir, & M. Farrow (Eds.), Proceedings of the 5th international colloquium on working equines. The future for working equines. Ethiopia: Addis Ababa. 2006.

- Burden FA, Du Toit N, Hernandez-Gil M, Prado-Ortiz O, Trawford AF. Selected health and management issues facing working donkeys presented for veterinary treatment in rural Mexico: some possible risk factors and potential intervention strategies. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2010; 42: 597-605.

- Getachew MA, Trawford G, Feseha G, Geid JSW. Gastrointestinal nematodes of donkeys (Equus asinus) in Khartoum state, Sudan. J Anim Vet Adv. 2010; 3: 736-739.

- Hosseini SH, Meshgi B, Eslami A, Bokai S, Sobhani M, Ebrahimi SR. Prevalence and biodiversity of helminth parasites in donkeys (Equus asinus) in Iran. Int J Vet Res. 2009; 3: 95-99.

- Al-Qudari A, Al-Ghamdi G, Al-Jabr O. Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites in horses in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia. SJKFU. 2015; 16: 37-47.

- Arfaei AA, Rasooli A, Razi JM, Hamidinejad H, Rouhizadeh A, Raki AR. Equine theileriosis in two Arab mares in Ahvaz. Iranian J Vet Res. 2013; 9: 103-108.

- Radostitis OM, Gay CC, Hinchclif KW, Constable PD. A textbook of the disease of cattle, sheep, goats, pigs and horse: Veterinary medicine 10th ed. UK: Baillere, Jindall. 2006: 1556-1586.

- Bowman DD. Parasitology for veterinarians. 8th ed. New York, USA: Saunders. 2003: 155-184.

- Mandal SC. Veterinary Parasitology at a Glance. 2nd ed. Revised andenlarged edition (Based on new VCL syllabus). 2012: 230-236.

- European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP). A Guide to the Treatment and Control of Equine Gastrointestinal Parasite Infections. ESCCAP Guideline 08 2nd ed., March 2019. Malvern Hills Science Park, Geraldine Road, Malvern, Worcestershire, WR14 3SZ, United Kingdom. 2019.

- Shite A, Admassu B, Abere A. Large Strongyle Parasites in Equine: AReview. Adv Biol Res. 2015; 9: 247-252.

- Radostits OM, Gay CC, Hinchcliff KW, Constables PO. Veterinary medicine, a text book of the disease of cattle, horse, sheep, pig and goats. 10th ed. London. 2007: 1558-1562.

- Lefevre PC, Blancou J, Chermette R, Ulienberg G. Infectious and parasitic disease of livestock. French. 2010; 2: 1530-1544.

- Saeed K, Qudir Z, Ashraf K, Ahmad N. Role of intrinsic and extrinsic epidemiological factors on strongylosis in horses. J Animal Public Sci. 2010; 20: 277-280.

- Nielsen MK, Kaplan RM, Thamsborg SM, Monrad J, Olsen SN. Climatic influences on development and survival of free-living stages of equine strongyles: implications for worm control strategies and managing anthelmintic resistance. Vet J. 2007; 174: 23-32.

- Kaur S, Singh E, Singla LD. Strongylosis in equine: An overview. J Entomology and Zoology Stud. 2019; 7: 43-46.

- Khan MA, Roohi N, Rana MAA. Strongylosis in Equines: a Review. JAnimal Plant Sci. 2015; 25: 1-9.

- Kuzmina TA, Lyons ET, Tolliver SC, Dzeverin II, Kharchenko VA.Fecundity of various species of strongylids (Nematoda: Strongylidae)--parasites of domestic horses. Parasitol Res. 2012; 111: 2265-2271.

- Kaplan RM, Klei TR, Lyons ET, Lester G, Courtney CH, French DD, et al. Prevalence of anthelmintic resistant cyathostomes on horse farms. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004; 225: 903-910.

- Reinemeyer CR. Controlling Strongyle Parasites of Horses. A Mandatefor Change 352 Special Lectures. 55. AAEP Proceedings. 2009.

- Lichtenfels JR, Kharchenko VA, Dvojnos GM. Illustrated identification keys to strongylid parasites (Strongylidae: Nematoda) of horses, zebras and asses (Equidae). Vet Parasitol. 2008; 156: 4-161.

- Andersen UV, Haakansson IT, Roust T, Rhod M, Baptiste KE, Nielsen MK. Developmental stage of strongyle eggs affects the outcome variations of real-time PCR analysis. Vet Parasitol. 2013; 191: 191- 196.

- Anutescu SM, Buzatu MC, Gruianu A, Bellaw J, Mitrea IL, Ionita M. Use of larval cultures to investigate the structure of strongyle populations in working horses, Romania: preliminary data. Agro Life Scientific J. 2016; 5: 9-14.

- Braga FR, Araújo JV, Silva AR, Carvalho RO, Araujo JM, Ferreira SR, et al. Viability of the nematophagous fungus Pochonia chlamydosporia after passage through the gastrointestinal tract of horses. Vet Parasitol. 2010; 168: 264-268.

- Saeed JZ, Qadir KA, Ahmed N. Role of intrinsic and extrinsic epidemiological factors on stronglosis in horses. J Anim Plant Sci. 2008; 18: 2-3.

- Gasser RB, Hung GC, Chilton NB, Beveridge I. Advances in developing molecular-diagnostic tools for strongyloid nematodes of equids: fundamental and applied implications. Mol Cell Probes. 2004; 18: 3-16.

- Marquartd C, Riochard S, Robert D, Grieve B. Parasitology and vectorbiology. 2nd ed. Canada Harcourt Academic press. 2000: 381-385.

- Scala A, Tamponi C, Sanna G, Predieri G, Meloni L, Knoll S, et al. Parascaris spp. eggs in horses of Italy: a large-scale epidemiological analysis of the egg excretion and conditioning factors. Parasit Vectors. 2021; 14: 246.

- Ayele G, Feseha G, Bojia E, Joe A. Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites of donkeys in Dugda Bora District, Ethiopia. J Livest Res Rural Dev. 2006; 18: 2-6.

- Reinemeyer CR, Nielsen MK. Control of helminth parasites in juvenile horses. Equine Vet Educ. 2017; 29: 225-232.

- Lyons ET, Tolliver SC. Strongyloides westeri and Parascaris equorum: observations in field studies in thoroughbred foals on some farms in Central Kentucky, USA. Helminthologia. 2014; 51: 7-12.

- Robert M, Hu W, Nielsen MK, Stowe CJ. Attitudes towards implementation of surveillance-based parasite control on Kentucky Thoroughbred farms - Current strategies, awareness and willingness- to-pay. Equine Vet J. 2015; 47: 694-700.

- Cooper LG, Caffe G, Cerutti J, Nielsen MK, Anziani OS. Reduced efficacy of ivermectin and moxidectin against Parascaris spp. in foals from Argentina. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Rep. 2020; 20: 100388.

- Armstrong SK, Woodgate RG, Gough S, Heller J, Sangster NC, Hughes KJ. The efficacy of ivermectin, pyrantel and fenbendazole against Parascaris equorum infection in foals on farms in Australia. Vet Parasitol. 2014; 205: 575-580.

- Peregrine AS, Molento MB, Kaplan RM, Nielsen MK. Anthelmintic resistance in important parasites of horses: does it really matter?. Vet Parasitol. 2014; 201: 1-8.

- Veronesi F, Moretta I, Moretti A, Fioretti DP, Genchi C. Field effectiveness of pyrantel and failure of Parascaris equorum egg count reduction following ivermectin treatment in Italian horse farms. Vet Parasitol. 2009; 161: 138-141.

- Attia MM, Khalifa MM, Mahdy OA. The prevalence of Gasterophilus intestinalis (Diptera: Oestridae) in donkeys (Equus asinus) in Egypt with special reference to larvicidal effects of neem seed oil extract (Azadirachta indica) on third stage larvae. Open Vet J. 2018; 8: 423- 431.

- Otranto D, Milillo P, Capelli G, Colwell DD. Species composition of Gasterophilus spp. (Diptera, Oestridae) causing equine gastric myiasis in southern Italy: parasite biodiversity and risks for extinction. Vet Parasitol. 2005; 133: 111-118.

- Giglioti R, Forim MR, Oliveira HN, Chagas AC, Ferrezini J, Brito LG, et al. In vitro acaricidal activity of neem (Azadirachta indica) seed extracts with known azadirachtin concentrations against Rhipicephalus microplus. Vet Parasitol. 2011; 181: 309-315.

- Abdel-Ghaffar F, Al-Quraishy S, Al-Rasheid KA, Mehlhorn H. Efficacy of a single treatment of head lice with a neem seed extract: an in vivo and in vitro study on nits and motile stages. Parasitol Res. 2012; 110: 277-280.

- Ruchi T, Amit KV, Sandip C, Kuldeep D, Shoor VS. Neem (Azadirachta indica) and its Potential for Safeguarding Health of Animals and Humans: A Review. J Biol Sci. 2014); 14: 110-123.

- Reinemeyer CR, Nielsen MK. Review of the biology and control of O xyuris equi. Equine veterinary education. 2014; 26: 584-591.

- Kouidri M, Boumezrag A, Mohmmed SSA, Touihri Z, Sassi A, Chibi A. First study on Oxyuriosis in horses from Algeria: Prevalence and clinical aspects. J Hellenic Veterinary Medical Society. 2021; 72: 3179-3184.

- Nielsen MK, Reinemeyer CR, Sellon DC. Nematodes. Equine.Infectious. Diseases. 2014; 475-489.e4.

- Olliver SC, Lyons ET, Nielsen MK, Bellaw JL. Transmission of some species of internal parasites in horse foals born in 2013 in the same pasture on a farm in Central Kentucky. Helminthologia. 2015; 52: 211.

- Smith PB. Large animal internal medicine, 4th Ed., USA, Mosby Elsevier of Lalitpur District. 2009: 232-321.

- Feye A, Bekele T. Prevalence of Equine Lung Worm (Dictyocaulus Arnfieldi) and Its Associated Risk Factors in Jimma Town, South West Ethiopia. Adv Life Sci Technol. 2016; 40: 26-30.

- Abdisa T. Review on Dictyocaulosis and Its Impact in Equines. WorldJ Adv Healthcare Res. 2018; 2: 22-28.

- Saadi A, Tavassoli M, Dalir-Naghadeh B, Samiei A. A survey of Dictyocaulus arnfieldi (Nematoda) infections in equids in Urmia region, Iran. Ann Parasitol. 2018; 64: 235-240.

- Lyons ET, Tolliver SC, Drudge JH, Swerczek TW, Crowe MW. Lungworms (Dictyocaulus arnfieldi): prevalence in live equids in Kentucky. Am J Vet Res. 1985; 46: 921-923.

- Hodgson JL, Hodgson DR. Collection and analysis of respiratory tract samples. In Equine respiratory medicine and surgery. WB Saunders. 2007: 119-150.

- Over HJ, Jansen J, Van Olm PW. Distribution and impact of helminth diseases of livestock in developing countries. Food & Agriculture Org. 1992; 96.

- Junquera P. Dictyocaulus species, parasitic lungworms of Cattle, Sheep, Goats and other Livestock. Biology, prevention and control. Dictyocaulus filaria, Dictyocaulus viviparus, Dictyocaulus arnfieldi. In: Merck Veterinary Manual, Merck and Co, Inc, Whitehouse Station, N.J., USA. 2014; 14: 28.

- Johnson M, MacKintosh G, Labes E, Taylor J, Wharton A. Dictyocaulus species. Cross infection between cattle and red deer. New Zealand Veterinary J. 2003; 51: 93-98.