Preliminary Study on the Cross transmission of Digestive Strongyle Nematodes between Humans and Small Ruminants in the Foto Group, Dschang, West Cameroon

- 1. Department of Animal Biology, University of Dschang, Cameroon

Abstract

In areas where humans coexist with small ruminants, the circulation of gastrointestinal nematodes between these two species warrants investigation. The aim of this study was to identify strongyle nematodes with zoonotic potential and to assess the risk factors associated with their cross-transmission between small ruminants and humans in the locality of Foto-Dschang Cameroon. A total of 220 stool samples were collected from households where small ruminants were raised, including 76 from humans and 144 from goats and sheep. Once collected, the samples were sent to the laboratory for qualitative and quantitative coproscopic analysis. Digestive strongyle eggs found in the stool were identified based on their morphometric and morphological characteristics using identification key. Risk factors were assessed through a questionnaire administered to small ruminant owners in the Foto group. As result, seven species of digestive strongyles were identified in both humans and small ruminants. Trichostrongylus sp. 74 (55.1%) and Haemonchus contortus 25 (18.6%) were the most prevalent. Among these strongyle nematodes, three species were involved in the cross-transmission between humans and small ruminants: Trichostrongylus sp, Haemonchus contortus, and Cooperia curticei. The overall prevalence of digestive strongyles was 15.8% in humans and 61.8% in small ruminants. The primary risk factors associated with the cross-transmission of digestive strongyles included poor food hygiene, lack of hand hygiene, close contact with small ruminants, and stray farming practices. Although molecular identification of the strongyle found is needed for confirmation, the findings underscore the urgent need for the implementation of control strategies to protect the health of local populations and ensure the sustainability of small ruminant farming.

Keywords

• Foto

• Humans

• Small Ruminants

• Strongyle Nematodes

• Cross Transmission

Citation

Flavie DA, Gertrude MT, Gabriel TH, Sognia NT, Joel ATR (2025) Preliminary Study on the Cross-transmission of Digestive Strongyle Nema todes between Humans and Small Ruminants in the Foto Group, Dschang, West Cameroon. J Vet Med Res 12(3): 1289

INTRODUCTION

Small ruminant farming plays a vital role in Cameroon’s economy, providing sources of meat, milk, fiber, cash income, and leather. These animals are well adapted to extreme climatic conditions, can graze on forage unsuitable for larger ruminants, and require relatively low labor intensive inputs [1]. In many developing countries, the production performance of sheep and goats is hindered by poor management practices and diseases caused by various pathogens, including gastrointestinal strongyle nematodes. Strongylid nematodes are of significant research interest due to their ability to infect humans and other vertebrate hosts [2,3]. These nematodes predominantly inhabit the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems of their hosts, where they feed on blood or tissues [4,2]. Some species can survive for many years within their hosts, and severe infections can result in inflammatory responses, lesions, significant weight loss, anemia, and malnutrition [5]. In humans, the most notable strongylids are hookworms (Necator americanus, Ancylostoma duodenale, and Ancylostoma ceylanicum), which infect over 400 million people globally [6]. Among the most significant genera of nematodes recognized as major endoparasites causing health and production challenges in livestock industries worldwide are Teladorsagia, Haemonchus, Trichostrongylus, Cooperia, and Marshallagia [7]. In certain urban areas, such as Foto, a locality in Dschang, Cameroon, humans who breed small ruminants often share their homes with sheep and goats. This close co-existence, combined with poor hygiene practices over time, can sometimes result in undesirable outcomes, such as the transmission of zoonotic diseases. Strongyle nematodes, which have free-living stages in the environment, facilitate their transmission across various host species. In Isfahan, Iran, four genera of gastrointestinal nematodes from small ruminants (Teladorsagia, Haemonchus, Trichostrongylus, and Marshallagia) have been reported in humans [7]. In humans, heavy infections with these parasites can lead to symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, anorexia, nausea, weakness, mild anemia, low-grade peripheral eosinophilia, pulmonary and cutaneous symptoms, and, if left untreated, even death [8]. The ‘One Health’ approach emphasizes the importance of concurrently monitoring zoonotic pathogens that affect both humans and animals sharing the same environment [9]. Unfortunately, this integrated approach is not yet implemented in Cameroon. Most studies focus on gastrointestinal nematodes in small ruminants, and reports on the prevalence of zoonotic gastrointestinal nematodes in humans remain scarce.

This study is a pioneering effort to evaluate the potential zoonotic transmission of gastrointestinal strongyle nematodes in Cameroon. The findings may provide valuable insights that could aid in the development of effective control strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

The present study was conducted in the rural areas of the Foto group, located in the Menoua Department of West Cameroon. The Foto group extends to the north and east of the commune of Dschang, covering an area of 99 km², which represents 37.8% of the total communal territory. The group consists of both urban and rural areas, with a predominantly agricultural population, estimated at approximately 17,934 inhabitants in 2024 [10]. Situated at an altitude of 1,393 meters, the region experiences a dry season lasting 4 months and a rainy season spanning 8 months (from March to November). The Foto group is made up of 52 villages, and for this study, 15 villages were selected based on their accessibility.

Type of Study and Study Population

This study was a cross-sectional prospective investigation. Recruitment of participants began on March 16, 2024, and concluded on May 5, 2024. The study population consisted of small ruminants and humans living in households where these animals were raised.

Sample Collection

Human and small ruminant samples were collected from 123 households distributed across 15 villages in the Foto group. Fresh fecal samples were taken from 76 humans and 144 small ruminants, after confirming that neither had received anthelmintic treatment within 3 months prior to the study. Sterile stool jars, labeled and coded, were given to each human participant in the evening, with instructions on how to collect the stool during the first hour of the following morning. Participants were instructed to use the provided container to collect freshly emitted stool, avoiding contact with urine whenever possible. For small ruminants, approximately 5g of feces were collected directly from the rectums of goats and sheep using nursing gloves. All samples were placed in sterile jars labeled with the corresponding household code. The stool samples were preserved in 10% formalin and transported to the laboratory for parasitological analysis.

Parasitological Analysis

Both qualitative and quantitative coproscopies were performed using the Willis flotation technique and the McMaster method, respectively.

Qualitative Coproscopy: Strongyle eggs were identified using the Willis flotation technique. To perform this method, 2g of stool were weighed, placed in a mortar, and crushed. Then, 60 ml of 40% saline solution was added, and the mixture was homogenized and filtered using a fine mesh strainer. The resulting filtrate was transferred into two test tubes to form a convex meniscus. Coverslides were carefully placed on the menisci, avoiding air bubbles, and left to rest for 5 minutes. After this time, the coverslides were removed and placed on object slides for observation under a microscope with a 10X objective.

The number of positive samples was used to calculate the prevalence of digestive strongyles in humans and small ruminants using the following formula (1):

Where: n = number of positive cases and N = total number of samples examined

Quantitative Coproscopy: The McMaster technique was used to count strongyle eggs in samples that tested positive in the flotation technique. The remaining filtrate was transferred into the two chambers of the McMaster cell using a Pasteur pipette. After 5 minutes, the eggs were counted under the microscope using a 4X objective. The egg count was performed according to the standard method outlined by Soulsby [11].

Identification of Strongyle Eggs Found in Stool Samples

Strongyle eggs were identified based on their morphological characteristics (shape and size) as described by Soulsby [11]. and Thienpont et al. [12]. Size was measured using a calibrated micrometer in the 10X objective lens of the microscope.

Questionnaire Survey

During sample collection, a questionnaire was administered to human participants to identify risk factors related to the cross-transmission of digestive strongyles between humans and small ruminants. The questionnaire collected information on hygiene practices, interactions with small ruminants, water supply, farm management, veterinary care, and anthelmintic treatments. Due to the low educational level of many participants, questions were asked directly, and the forms were completed by the research team. Observations of the habitat were also recorded.

Data Analysis

The data collected were recorded in Microsoft Excel 2016 and transferred to SPSS version 20 for statistical analysis. A chi-square test was used to assess the association between the occurrence of gastrointestinal parasites and socio-demographic factors, as well as the villages of participants. The ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) test was used to compare the means of strongyle intensity in humans, while the T-test was used to compare the means of strongyle species according to the type of small ruminant. Odds ratios were calculated to assess risk factors. For all analyses, a significance level of P < 0.05 was considered.

RESULTS

RESULTS Presentation of strongyle nematodes identified in the study population

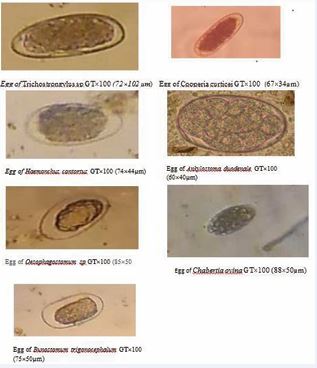

Figure 1 Pictures of strongyle nematode eggs found in faeces of study populations

Seven species of digestive strongyles were identified in both humans and small ruminants [Figure 1] namely Trichostrongylus sp, Haemonchus contortus, Cooperia curticei, Ankylostoma duodenale, Oesophagostomum sp, Bunostomum sp and Chabertia ovina.

Table 1: Percentage of digestive strongyle species found in stool samples from humans and small ruminants.

|

Species |

Number |

Percentage (%) |

|

Trichostrongylus sp Haemonchus contortus Cooperia curticei Ankylostoma duodenale Oesophagostomum sp Bunostomum sp Chabertia ovina |

74 25 15 3 5 4 5 |

55.1 18.6 11.5 3.9 3.5 2.8 3.5 |

[Table 1], presenting the percentage of strongyle nematode in the study population revealed that Trichostrongylus sp was the most prevalent 74 (55.1%) followed by Haemonchus contortus 25 (18.6%).

Strongyle species involved in cross-transmission

Table 2: Presentation of strongyle nematode species probably involved in cross transmission.

|

Espèces |

Humans |

Small ruminants |

Common |

|||

|

|

Condition |

n(%) |

Condition |

n(%) |

Condition |

n(%) |

|

Trichostrongylus sp |

Present |

6(7.9) |

Present |

68(47.2) |

Present |

74(55.1) |

|

Haemonchus contortus |

Present |

2(2.6) |

Present |

23(16) |

Present |

25(18.6) |

|

Cooperia curticei |

Present |

3(3.6) |

Present |

11(7.6) |

Present |

14(11.2) |

|

Oesophagostomum sp |

Absent |

0(00) |

Present |

5(3.5) |

Absent |

0(00) |

|

Bunostomum trigonocephalum |

Absent |

0(00) |

Present |

4(2.8) |

Absent |

0(00) |

|

Chabertia ovina |

Absent |

0(00) |

Present |

5(3.5) |

Absent |

0(00) |

As shown in [Table 2], four species were identified in the human population: Trichostrongylus sp, Haemonchus contortus, Cooperia curticei and Ankylostoma duodenale. In contrast six species were found in small ruminants: Trichostrongylus sp, Haemonchus contortus, Cooperia curticei, Oesophagostomum sp, Bunostomum trigonocephalum and Chabertia ovina. Therefore, three species were found in both populations, namely Trichostrongylus sp, Haemonchus contortus and Cooperia curticei.

Prevalence and intensity of digestive strongyles in humans

From [Table 3], twelve peoples out of the seventy-six sampled were infested with digestive strongyles, giving prevalence of 15.8%; with an average intensity of 263±139 eggs per gram of faeces (EPG).

Table 3: General prevalence and intensity of strongyle infestations in humans sampled in the Foto grouping.

|

Results |

Prevalence n (%) |

EPG Mean±sd |

|

Positive |

12 (15.8) |

263±139 |

|

Negative Total |

64 (84.2) 76 (100) |

0 263±139 |

Prevalence and intensity of digestive strongyles in humans according to socio-demographic factors

Table 4: Prevalence and intensity of digestive strongyles in humans according to sociodemographic factors.

|

Caracteristics |

N |

Infested individuals |

Trichostrongylus sp |

Ancylostoma duodenale |

Haemonchus contortus |

Cooperia curticei |

|||||

|

|

|

n(%) |

EPG ± σ |

n(%) |

EPG ± σ |

n(%) |

EPG ± σ |

n(%) |

EPG ± σ |

n(%) |

EPG ± σ |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male |

42 |

7(9.2) |

311± 188 |

3(3.9) |

200±0,00 |

1(1.3) |

200±0.00 |

1(1.3) |

300±0.00 |

2(2.6) |

250±70 |

|

Female |

34 |

5(6.6) |

214± 89 |

3(3.9) |

466±230 |

2(2.6) |

200±0.00 |

1(1.3) |

200±0.00 |

1(1.3) |

200±00 |

|

P-value |

- |

0.81 |

- |

0.556 |

- |

0.42 |

- |

0.698 |

- |

0.58 |

- |

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[0-5] |

17 |

2(2.6) |

400±282 |

2(2.6) |

400±282 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

- |

|

[6-10] |

28 |

7(9.2) |

300±152 |

3(3.9) |

333±230 |

1(1.3) |

200±00 |

1(1.3) |

200±00 |

2(2.6) |

250±70 |

|

[11-15] |

24 |

2(2.6) |

200±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

2(2.6) |

200±00 |

1(1.3) |

300±00 |

1(1.3) |

200±00 |

|

[16-20] |

5 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

[21-25] |

1 |

1(1.3) |

200±00 |

1(1.3) |

200±0,00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

[+26[ |

1 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

P-value |

- |

0.12 |

- |

0.06 |

- |

0.719 |

- |

0.907 |

- |

0.769 |

- |

|

Study level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

None |

11 |

1(1.3) |

600±00 |

1(1.3) |

200±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

Primary |

48 |

10(13.2) |

270±133 |

4(5.3) |

466±230 |

3(3.9) |

333±230 |

2(2.6) |

250±70 |

2(2.6) |

250±70 |

|

Secondary |

16 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

Superior |

1 |

1(1.3) |

200±00 |

1(1.3) |

200±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

200±00 |

|

P-value |

- |

0.015 |

- |

0.05 |

- |

0.41 |

- |

0.6 |

- |

- |

- |

Table 4 presents the prevalence and intensity of digestive strongyles in humans according to socio demographic factors, indicates that males had a higher infestation rate (9.2%) compared to females (6.6%). At least one type of digestive strongyle was found in both sexes. Children aged 6 to 10 years exhibited the highest infestation rate (9.2%), which correlates with the infestation patterns observed according to education level, where elementary school children had the highest parasitism rate (13.2%). Overall, the infestation by strongyle nematodes was light across all categories, with an EPG (eggs per gram) of less than 500, except in individuals with no education, where a moderate infestation was observed with an EPG of 600±00.

Prevalence and intensity of digestive strongyles in humans according to villages

Table 5: Prevalence and intensity of digestive strongyles in humans according to villages.

|

Villages |

N |

Infested individuals |

Trichostrongylus sp |

Ancylostoma duodenale |

Haemonchus contortus |

Cooperia curticei |

|||||

|

|

|

n(%) |

EPG ± σ |

n(%) |

EPG ± σ |

n(%) |

EPG ± σ |

n(%) |

EPG ± σ |

n(%) |

EPG ± σ |

|

Azon |

3 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

Balevouli |

3 |

1(1.3) |

300±0 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

1(1.3) |

300±00 |

|

Fiakop |

6 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

Fonakeukeu |

6 |

1(1.3) |

200±0 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

Fotchouli |

2 |

1(1.3) |

200±0 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

1(1.3) |

200±00 |

|

Kelen |

11 |

1(1.3) |

250±0 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

1(1.3) |

200±00 |

1(1.3) |

300±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

Lefatsa |

5 |

2(2.6) |

400±282 |

1(1.3) |

600±00 |

1(1.3) |

200±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

Léfè |

4 |

1(1.3) |

200±0 |

1(1.3) |

200±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

Lefee |

2 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

Loung |

5 |

1(1.3) |

200±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

1(1.3) |

200±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

Toula djizon |

4 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

Tschoafeu |

4 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

Tsinbing |

11 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

Tsinkop |

5 |

4(5.3) |

350±191 |

4(5.3) |

300±200 |

1(1.3) |

200±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

Toutsang |

5 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

0(0.0) |

00±00 |

|

P-Value |

- |

0.03 |

- |

0.025 |

- |

0,737 |

- |

0.959 |

- |

0,55 |

- |

Table 5 presents the prevalence and intensity of digestive strongyles in humans according to villages. Out of the 15 villages sampled in the foto group, the human population was free of digestive strongyle in 6 villages. Individuals living in Tsinkop were the most infested 4 (5.3%).

Prevalence and intensity of digestive strongyles in small ruminants

General prevalence and intensity: Eighty-nine animals out of one hundred and forty-four examined were infested with digestive strongyles, giving a prevalence of 61.8%. The average fecal egg concentration recorded was 538±505 EPG [Table 6].

Table 6: General prevalence of digestive strongyles of small ruminants from the Foto group.

|

Results |

Prevalence n(%) |

EPG Mean±Sd |

|

positive |

89 (61.8) |

538±505 |

|

Negative Total |

55 (38.2) 144 (100) |

0 -- |

Prevalence and intensity of digestive strongyle species according to type of small ruminants: From [Table 7], Goats were more infested 54 (37.5%) than sheep 35(24.3). The highest EPG was recorded in sheep that is 557±573. Goats and sheep were infested with all the 6 types of digestive strongyles.

Table 7: Prevalence and intensity of digestive strongyles according to the type of small ruminants.

|

Type of small ruminants |

N |

Infested individual |

Trichostrongylus sp |

Oesophagostomum sp |

Bunostomum trigonocephalum |

Cooperia curticei |

Chabertia ovina |

Haemonchus contortus |

||||||

|

n (%) |

n (%) |

EPG ± σ |

n (%) |

EPG ±σ |

n (%) |

EPG ± σ |

n (%) |

EPG ± σ |

n (%) |

EPG ± σ |

n (%) |

EPG ± σ |

||

|

Goats |

89 |

54(37.5) |

46(31.9) |

460±447 |

2(1.4) |

200±0 |

3(2.1) |

200±0 |

6(4.2) |

200±0 |

4(2.8) |

200±0 |

12(8.3) |

366±115 |

|

Sheep |

55 |

35(24.3) |

22(15.3) |

566±693 |

3(2.1) |

500±435 |

2(1.4) |

350±212 |

5(3.5) |

200±0 |

1(0.7) |

200±0 |

11(7.6) |

390±280 |

|

P-Value |

|

0.3 |

_ |

_ |

|

_ |

|

_ |

|

_ |

|

_ |

|

0.48 |

Prevalence and intensity of digestive strongyle species in small ruminants according to villages: Table 8 summarizes the prevalence and intensities of the digestive strongyle species of small ruminants according to the villages. The villages that had the highest prevalence were Tsinbing and Tsinkop, i.e. 13 (9%. The highest intensity (2133±1301) was recorded in the village Tsinbing with Trichostrongylus sp.

Table 8: Prevalence and intensity of digestive strongyles in small ruminants according to villages.

|

Villages |

N |

Infested Individual |

Trichostrongylus sp |

Oesophagostomum sp |

Bunostomum trigonocephalum |

Cooperia curticei |

Chabertia ovina |

Haemonchus contortus |

||||||

|

n (%) |

n (%) |

EPG ± σ |

n (%) |

EPG ±σ |

n (%) |

EPG ± σ |

n (%) |

EPG ± σ |

n (%) |

EPG ± σ |

n (%) |

EPG ± σ |

||

|

Azon |

5 |

0(0.0) |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

|

Balevouli |

7 |

4(2.8) |

5(3.5) |

575±262 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

2(1.4) |

300±141 |

|

Fiakop |

11 |

5(3.5) |

4(2.8) |

275±150 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

1(0.7) |

200±0 |

1(0.7) |

200±0 |

1(0.7) |

400±0 |

|

Fonakeukeu |

6 |

3(2.1) |

4(2.8) |

333 ±152 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

1(0.7) |

600±00 |

|

Fotchouli |

6 |

4(2.8) |

3(2.1) |

200±0 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

2(1.4) |

200±0 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

1(0.7) |

200±0 |

|

Kelen |

11 |

7(4.9) |

3(2.1) |

400±0 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

1(0.7) |

500±00 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

|

Lefatsa |

9 |

7(4.9) |

3(2.1) |

433±115 |

2(1.4) |

600±565 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

1(0.7) |

200±0 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

2(1.4) |

500±141 |

|

Léfè |

8 |

6(4.2) |

5(3.5) |

340±207 |

2(1.4) |

250±70 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

2(1.4) |

200±0 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

|

Lefee |

3 |

1(0.7) |

4(2.8) |

333±230 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

1(0.7) |

200±0 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

1(0.7) |

200±0 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

|

Loung |

12 |

7(4.9) |

1(0.7) |

200±0 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

1(0.7) |

200±0 |

4(2.8) |

200±0 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

3(2.1) |

466±115 |

|

Toula djizon |

14 |

12(8.3) |

3(2.1) |

500±264 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

1(0.7) |

200±0 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

3(2.1) |

266±115 |

|

Tschoafeu |

8 |

5(3.5) |

12(8.3) |

375±237 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

1(0.7) |

200±0 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

2(1.4) |

300±00 |

|

Tsinbing |

28 |

13(9) |

3(2.1) |

2133±1301 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

1(0.7) |

200±0 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

5(3.5) |

260±00 |

|

Tsinkop |

13 |

13(9) |

9(6.3) |

377±171 |

1(0.7) |

|

0(0.0) |

_ |

1(0.7) |

200±0 |

1(0.7) |

200±0 |

1(0.7) |

500±00 |

|

Toutstang |

3 |

2(1.4) |

13(9) |

592±607 |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

0(0.0) |

_ |

2(1.4) |

650±00 |

|

P |

|

- |

0.25 |

0 .001 |

0.04 |

_ |

0.37 |

_ |

0.09 |

|

0.05 |

_ |

0,5 |

0,25 |

|

Total |

144 |

89(61.8) |

73(51.1) |

494±333 |

5(3.5) |

425±386 |

4(2.8) |

275±150 |

11(7.6) |

200±0 |

5(3.5) |

200±0 |

23(16) |

378±206 |

Risk factors related to cross-transmission

Table 9: Risk factors linked to cross-transmission of digestive strongyles between humans and small ruminants.

|

Factors |

N |

Percentage n(%) |

P |

Odds ratio |

95% CI |

P-Value |

||

|

Level of education |

||||||||

|

None |

11 |

1(1.3) |

0,022 |

0.047 |

[0.001-1.79] |

0.1001 |

||

|

Primary |

48 |

10(13.2) |

0.09 |

[0.004-2.39] |

0.151 |

|||

|

Secondary |

16 |

0(0.0) |

0.01 |

[0.0001-0.71] |

0.0346 |

|||

|

Superior |

1 |

1(1.3) |

|

|

-- |

|||

|

Washing fruits and vegetables with drinking water |

||||||||

|

No |

1 |

0(0.0) |

0.435 |

|

|

-- |

||

|

Sometime |

10 |

4(5.3) |

2.07 |

[0.68-63.42] |

0.6752 |

|||

|

Yes |

65 |

8(10.5) |

0.44 |

[0.01-11.79] |

0.6271 |

|||

|

Washing hands with clean water and soap before eating |

||||||||

|

No |

1 |

0(0.0) |

0.435 |

|

|

-- |

||

|

Sometime |

6 |

2(2.6) |

1.66 |

[0.04-58.28] |

0.7782 |

|||

|

Yes |

69 |

10(13.20) |

0.45 |

[0.017-11.87] |

0.6348 |

|||

|

Close contact with small ruminants |

||||||||

|

No |

3 |

0(0.0) |

0.444 |

|

|

-- |

||

|

Yes |

73 |

12(15.8) |

1.42 |

[0.06-29.30] |

0.8193 |

|||

|

Diagnosing humans with parasitic infestations |

||||||||

|

No |

16 |

5(6.6) |

0.056 |

|

|

-- |

||

|

Yes |

60 |

7(9.2) |

0.2906 |

[0.07-1.08] |

0.07 |

|||

|

Breeding method |

||||||||

|

Enclosure |

2 |

0(0.0) |

0.544 |

|

|

-- |

||

|

Pickets |

62 |

9(11.8) |

0.89 |

[0.04-19.98] |

0.94 |

|||

|

Wandering |

12 |

3(3.9) |

1.84 |

[0.07-48.68] |

0.71 |

|||

Legend: CI= Confidence Interval; N=Size of population.

Table 9 summarizes the risk factors linked to the crosstransmission of digestive strongyles between humans and small ruminants. It appears that cross-transmission of digestive strongyles between humans and small ruminants in the Foto village was linked to non or occasional washing of fruits and vegetables, wandering method of breeding, no or occasional washing of hand with potable water and soap and close contact with animals with odds ratio of 2.07, 1.84, 1.66 and 1.42 respectively.

Ethical Consideration

This study focused on digestive strongyles in humans. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Regional Health Delegation of the Western Region. Written informed consent was obtained from each adult participant prior to the administration of the questionnaire and stool sampling. For minor participants, parental consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Non-experimental animals were used in this study. Fecal samples were collected through non-invasive and non-painful procedures, following NIH Care guidelines.

DISCUSSION

At the conclusion of this study, which aimed to identify species of strongyles with zoonotic potential and assess the risk factors associated with their cross-transmission between small ruminants and humans in the villages of the Foto group, seven species of strongyles were identified in both humans and small ruminants. These included Trichostrongylus sp., Haemonchus contortus, Ancylostoma duodenale, Oesophagostomum sp., Cooperia curticei, Bunostomum trigonocephalum, and Chabertia ovina. The presence of these seven species reflects the parasitic diversity in the Foto group and underscores the importance of implementing sustainable control strategies for digestive strongyles in the region.

Trichostrongylus sp. and Haemonchus contortus were the most prevalent species, with prevalences of 74 (55.1%) and 25 (18.6%), respectively. Similar trends were observed by Makamté et al. [13], in their study of gastrointestinal strongyles in sheep in Nziih. According to Ashrafi et al. [14], the number of adult females of Trichostrongylus sp. and Haemonchus contortus present in the intestines of small ruminants is generally higher than that of other strongyle species. Consequently, the free-living stages of Trichostrongylus sp. and Haemonchus contortus are more abundant in pastures, facilitating their transmission and making them more likely to infest their hosts compared to other species, thereby explaining their predominance in both human and small ruminant populations.

Three species of strongyles were found to be common to both humans and small ruminants: Trichostrongylus sp., Haemonchus contortus, and Cooperia curticei. These species are likely responsible for the cross-transmission observed between the two populations. This finding aligns with the work of Ashrafi et al. [14], who studied the zoonotic transmission of digestive strongyles in northern Iran. Gastrointestinal parasites typically follow a specific life cycle, with a developmental phase in the host’s body before being excreted into the environment. These parasites can be found in the feces of infested animals, contaminating soil, grasses, and other surfaces. Humans may unintentionally contract these parasites when they come into contact with contaminated environments. In this study, the strongyles involved in cross-transmission were primarily those of small ruminants. Unlike animals, whose feces are commonly found in nature, human feces are rarely encountered in the environment, making contact between animal and human feces unlikely. Additionally, since strongyle eggs are initially found in feces, it is difficult for animals to contract strongyles from humans. However, humans have easier access to animal droppings, facilitating the risk of infestation.

The predominance of Trichostrongylus sp. and Haemonchus contortus suggests a higher risk of cross transmission between humans and small ruminants. These two species are widespread in small ruminants, which also explain their high prevalence in humans.

A total prevalence of 15.8% of digestive strongyles was observed in humans from the rural areas of Foto, with a mean intensity of 350±70 OPG (eggs per gram). This prevalence is similar to that reported by Ashrafi et al. [14], who recorded strongyle prevalences ranging from 0.4% to 18% in certain regions of Iran. Similarly, the study by Wabo et al. [15], on the prevalence and intensity of infections with the three most neglected diseases among patients at the Dschang health center showed a 10.7% prevalence of digestive strongyles. The higher prevalence in men compared to women may be due to greater exposure, as men are typically responsible for the care of animals in most households.

A higher educational level was associated with a lower prevalence of strongyle infestations in the inhabitants of the Foto villages. This observation aligns with several previous studies, including Kamau et al. [16], which linked education level with hygiene practices. Education appears to play a crucial role in reducing the prevalence of strongyles, particularly at the primary school level, where lack of hygiene knowledge and preventive measures against parasitic diseases make individuals more vulnerable to infestation. Therefore, incorporating educational programs into health interventions is essential to reduce the prevalence of strongyles and improve the overall health of the community.

Although children aged 6 to 10 years had the highest prevalence, children aged 0 to 5 years showed the highest average intensity. This could be due to their underdeveloped immune systems, as young children tend to explore their environment more and may have poor hygiene practices, increasing their exposure to parasites. This high intensity can lead to symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and anemia.

The overall prevalence of 61.8% of digestive strongyles observed in small ruminants in the rural areas of Foto indicates that a significant number of small ruminants are infested with these parasites. This result is consistent with findings by Makamté et al. [13], and Ntonifor et al. [17], who reported prevalences of 60.9% and 66.9% in small ruminants, respectively. These high prevalences can be attributed not only to weak husbandry practices but also to the environmental conditions in the study area. In Foto, strongyle infestations varied depending on the type of small ruminant and the rearing system. Goats were more heavily infested than sheep, possibly due to their larger size. Verheyden et al. [18], demonstrated a positive correlation between small ruminant density and strongyle infestations in France. However, while sheep had a lower prevalence, they had a significantly higher average fecal egg concentration than goats. This could be due to physiological, immune, or behavioral differences between the species. The high concentration of strongyle eggs in sheep feces reflects a weak immune system [19]. Sheep tend to graze at ground level, in close proximity to their feces, unlike goats, which graze higher up on grasses [18].

Strongyle infestations in small ruminants also varied according to villages. Tsinkop recorded the highest prevalence and intensity of digestive strongyles. The higher values in this village were attributed to the presence of a high proportion of sheep. As mentioned earlier, sheep have weaker immune systems and further contribute to pasture contamination, which increases the risk of infestation for goats. Additionally, small ruminant owners in the area often only deworm animals showing clinical signs of parasitosis, rather than routinely administering anthelmintics.

The survey conducted among farmers revealed that lack of food hygiene, inadequate hand hygiene, close contact with animals, and allowing small ruminants to roam freely were the main risk factors contributing to the cross-transmission of digestive strongyles between humans and small ruminants in the Foto group. People who did not wash or insufficiently washed fruits and vegetables before consumption were twice as likely to be exposed to strongyle transmission. In this area, small ruminant feces, which likely contain strongyle eggs, are used 100% for fertilizing crops, including market garden vegetables. Farmers who kept their animals confined or tied them to a stake were half as exposed to strongyles as those who allowed their animals to roam freely. In the rural areas of the Foto group, contaminated animal feces were found scattered throughout the environment, even in fields where market garden crops were grown. This practice facilitates the dispersal of strongyles into the environment. When conditions are favorable, the eggs in animal feces will hatch, and their glycogenic and lipid reserves enable them to escape and leave the feces. Once on the grass or vegetables, they undergo vertical migration, waiting for humans to harvest them [20]. This study also found that people who cleaned their farms regularly were less at risk of infestations than those who cleaned only every few months. The accumulation of feces in the environment creates a significant reservoir of parasites [14]. Regular cleaning helps reduce soil contamination and the risk of zoonotic transmission [1].

CONCLUSION

Assessing the risk of cross-transmission of digestive strongyles in humans and small ruminants in a given area is crucial for implementing effective health strategies. This preliminary study was conducted to contribute to the development of control strategies for digestive strongyles in the study area and beyond. While waiting for the confirmation by molecular identification, the results show that the strongylofauna responsible for strongyle infestations in the Foto villages consists of Trichostrongylus sp., Haemonchus contortus, Cooperia curticei, Oesophagostomum sp., Bunostomum trigonocephalum, Chabertia ovina, and Ancylostoma duodenale. The species Trichostrongylus sp., Haemonchus contortus, and Cooperia curticei are involved in cross-transmission between humans and small ruminants in the Foto villages. The prevalence and intensity of digestive strongyles in both humans and small ruminants in the Foto group are high and vary according to socio-demographic factors. The risk factors for cross-transmission include poor hygiene, close contact with animals, and free-range farming practices. The findings highlight the urgent need for rapid treatment of strongyle infestations in small ruminants to prevent transmission to humans. Regular hand washing and confinement of animals are essential to reduce the risk of cross-transmission and protect both human and animal health.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are sincerely grateful to the population of Foto group who accepted to take part to the study and give their approval for sample collections on their small ruminants.

CREDIT AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT

MBOGNING TAYO Gertrude and TSILA Henri Gabriel designed and supervised the study; DJOUELA Auriane Flavie carried out the study assisted by NGUEPNANG TOUKAM Sognia and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; ATIOKENG TATANG Rostand Joel conducted the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Feyisa B, Bayisa D. Prevalence of Heamonchosis in Small Ruminants and It Associated Risk Factors in and Around Ejere Town, West Shoa, Oromia, Ethiopia. Am J Biomed Res. 2019; 3.

- Anderson RC. Order Strongylida (the bursate nematodes). In Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates. Their Development and Transmission, second edition Wallingford: C.A.B. International, Unversity Press.2000; 41-229.

- Gonçalves ML, Araújo A, Ferreira LF. Human intestinal parasites in the past: new findings and a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003; 98: 103-118.

- ?ervená B, Vallo P, Paf?o B, Jirk? K, Jirk? M, Petrželková KJ, et al. Host specificity and basic ecology of Mammomonogamus (Nematoda, Syngamidae) from lowland gorillas and forest elephants in Central African Republic. Parasitology. 2017; 144: 1016-1025.

- Delano ML, Mischler SA, Underwood WJ. Biology and diseases of ruminants: sheep, goats and cattle. In Laboratory Animal Medecine, second edition. 2002; 519-614.

- Loukas A, Hotez PJ, Diemert D, Yazdanbakhsh M, McCarthy JS, Correa- Oliveira R, et al. Hookworm infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016; 2: 16088.

- Petstechian N, Kalani H, Faridnia H, Yousefi H. Zoonotic gastrointestinal nematodes (Trichostrongylus) from sheep and goat in Isfahan, Iran. Acta Scientiae. 2014; 42: 1-6

- Ghanbarzadeh L, Saraei M, Kia EB, Amini F, Sharifdini M. Clinical and haematological characteristics of human trichostrongyliasis. J Helminthol. 2019; 93: 149-153.

- Mbuthia P, Murungi E, Owino V, Akinyi M, Eastwood G, Nyamota R, et al. Potentially zoonotic gastrointestinal nematodes co-infecting free ranging non-human primates in Kenyan urban centres. Vet Med Sci. 2021; 7: 1023-1033.

- BUCREP. Recensement Général de l’Habitat de Population du Cameroun (RGHP) 2024 with Projections. Yaoundé, Cameroun. 2024.

- Soulsby EJL. Helminths, arthropods and protozoa of domesticated animals. 7th Edition Bailliere Tindall, London, UK. 1982; 809.

- Thienpont D, Rochette F, Vanparijs OFJ. Diagnosing helminthiasis by coprological examination. Janssen Animal Health. Third edition. 2003.

- Makamte TS, Yondo J, Mbogning TG, Mpoame M. Anthelminthic resistance of gastrointestinal strongyles infecting sheep in Nziih, west Cameroun. Ann Res Rev Biol. 2022; 37: 11-20.

- Ashrafi K, Sharifdini M, Heidari Z, Rahmati B, Kia EB. Zoonotic transmission of Teladorsagia circumcincta and Trichostrongylus species in Guilan province, northern Iran: molecular and morphological characterizations. BMC Infect Dis. 2020; 20: 28.

- Wabo P J, Mpoame M, Nkeng-Efouet PA, Bilong CF. Prevalence and intensity of infections of three negleted tropical diseases in patient consulted at a Traditional Health Care Centre in Dschang West Cameroon. Access Library J. 2012; 2: 24-28.

- Kamau M, Chasek P, O’Connor D. Educating children in good hygiene practices. Access Library J. 2018; 2: 34-38.

- Ntonifor H, Shei S, Ndaleh N, Mbunkur G. Epidemiological studies of gastrointestinal parasitic infections in ruminants in Jakiri, BuiDivision, and North West Region of Cameroon. J Vet Med Anim Health, 2013; 5: 344-352.

- Verheyden M, Charlier J, Rinaldi L. Strongyles of small ruminants: A review of the current knowledge and future perspectives. Veterinary Parasitology. 2020. 283: 109-155.

- Vande Velde F, Charlier J, Claerebout E. Farmer Behavior and Gastrointestinal Nematodes in Ruminant Livestock-Uptake of Sustainable Control Approaches. Front Vet Sci. 2018; 5: 255.

- Zajac AM. Gastrointestinal nematodes of small ruminants: life cycle, anthelmintics, and diagnosis. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2006; 22: 529-541.