Review on Brucellosis in Ethiopia Focusing on Small Ruminants

- 1. Animal Health Institute (AHI), Central Ethiopia

Abstract

Small ruminants play a crucial role in providing food, income, and foreign exchange in Ethiopia, with their meat serving as a major export commodity to Middle Eastern and African markets. However, various diseases, including brucellosis, adversely affect their productivity by causing reproductive failures, reduced meat and milk output, and limiting trade opportunities. Brucellosis, a bacterial zoonotic disease caused by species of the genus Brucella, ranks among the top five globally significant zoonoses. While Brucella species are not strictly host-specific, they exhibit host preference, B. melitensis primarily affects sheep and goats and is the most virulent for humans. Transmission occurs mainly through contact with aborted materials, which contain high concentrations of the bacteria, especially during abortion or parturition. Humans are commonly infected by consuming unpasteurized dairy products or through direct contact with infected animals, particularly during birthing processes. Infected females may suffer from abortion with retained placenta, which can lead to metritis, prolonged calving intervals, and sometimes permanent infertility. In males, the disease can result in orchitis, epididymitis, and impaired fertility. Accurate diagnosis of brucellosis requires laboratory confirmation through direct detection methods such as microscopic examination, bacterial culture, animal inoculation, serological testing, or molecular diagnostics. The economic impact of the disease in Sub-Saharan Africa is exacerbated by limited resources, underdeveloped veterinary infrastructure, and a high burden of other infectious diseases. Control of brucellosis in small ruminants relies on integrated approaches, including vaccination, rigorous biosecurity, and test-and-slaughter policies.

Keywords

• Abortion; Brucella melitensis; Brucellosis; Review; Small ruminant

Citation

Desa G (2025) Review on Brucellosis in Ethiopia Focusing on Small Ruminants. J Vet Med Res 12(3): 1290

INTRODUCTION

Ethiopia, home to the largest small ruminant population in Africa, with an estimated 42.9 million sheep and 52.5 million goats, relies heavily on these animals for livelihoods, especially among pastoral communities. Small ruminants are vital for food, income, and foreign exchange, as their meat is a key export to Middle Eastern and African markets [1]. However, their productivity is hindered by challenges such as feed shortages, poor husbandry, and diseases like brucellosis, which limit both domestic and export potential [2]. Despite this large livestock resource, Ethiopia has not fully capitalized on its benefits due to the prevalence of infectious diseases, with brucellosis being a major constraint in sheep and goat production [3,4]. The disease significantly impacts the economy through reproductive losses, decreased meat and milk yield, and trade restrictions [5]. Its persistence in Ethiopia and other developing countries is linked to a lack of control programs, underreporting, and weak veterinary infrastructure [6]. Brucellosis is caused by Brucella, a gram-negative, intracellular bacterium that affects a wide range of animals and humans. Although Brucella species are not host-specific, they show host preference, with B. melitensis primarily infecting sheep and goats, and being the most pathogenic to humans [7]. In animals, brucellosis commonly causes abortion, retained fetal membranes, and infertility. Transmission occurs via aborted materials, vaginal discharges, and unpasteurized milk [8]. Human infection can occur through consumption of raw dairy products or contact with infected animals, particularly during parturition or abortion [9]. Seroprevalence varies across regions and is influenced by animal, environmental, and management factors. Reports from Ethiopia show a wide range: 0.8% in Sidama [10], 6.50% in Chiro and Burka Dhintu districts of West Hararghe zone [11], 6.40 in Karohey zone of Somali regional state [12], 1.23% in Somali [12], 1.76% in Central Ethiopia [13], 3.5% in Tigray [14], 4.8% in Afar [15], and up to 50% in Borena [16]. These variations highlight the need for region-specific control measures and improved surveillance.

Although numerous studies have been carried out on brucellosis in small ruminants across Ethiopia, the available information remains fragmented and lacks a comprehensive synthesis. As a result, a clear and consolidated understanding of the disease’s prevalence, distribution, and impact is still missing. To address this gap, it is essential to gather, organize, and analyze the most recent research findings related to brucellosis in sheep and goats. Therefore, the primary aim of this work is to review and compile up-to-date data on small ruminant brucellosis in order to provide a clearer epidemiological picture and support informed decision-making for disease control and prevention strategies.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The Causative Agent

Brucella is a Gram-negative, facultative intracellular bacterium capable of infecting a wide range of animal species, including humans. The genus Brucella comprises ten recognized species, including six classical species; B. abortus, B. melitensis, B. suis, B. ovis, B. canis, and B. neotomae—alongside four additional species identified more recently [17]. In small ruminants, brucellosis is mainly caused by Brucella melitensis and B. ovis, with occasional cases attributed to B. abortus [18]. Sheep and goats typically contract the disease through ingestion of feed or water contaminated with infectious materials or through sexual transmission. Brucella abortus is primarily responsible for bovine brucellosis and mainly affects cattle. However, it can also infect other species such as sheep, pigs, dogs, and horses. Additionally, cattle may contract infections from B. suis or B. melitensis when sharing grazing land or facilities with infected pigs, goats, or sheep. Infections in cattle caused by non-host-specific Brucella species tend to be less persistent than those caused by B. abortus [19].

Resistance and survival properties: Under appropriate conditions, Brucella organisms can survive in the environment for a very long period. Their ability to withstand inactivation under natural conditions is relatively high compared with most other groups of non spore forming pathogenic bacteria [20]. Brucella spp is sensitive to pasteurization temperatures and its survival outside the host is largely dependent on environmental conditions. The pathogen may survive in aborted fetus in the shade for up to eight months, for two to three months in wet soil, one to two months in dry soil, three to four months in faeces, and eight months in liquid manure tanks [21]. Survival is prolonged at low temperatures and organisms will remain viable for many years in frozen tissues. Brucella in aqueous suspensions is readily killed by most disinfectants. A 10g/l solution of phenol will kill Brucella in water after less than 15 minutes exposure at 37C0. Formaldehyde solution is the most effective of the commonly available disinfectants, provided that the ambient temperature is above 150C [20].

Epidemiology of Brucellosis

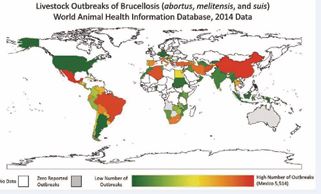

Brucellosis has been successfully controlled or eradicated in most developed countries, largely due to the implementation of comprehensive and well-resourced control programs. In contrast, the disease continues to pose significant economic and public health challenges in many developing nations, where large populations depend heavily on livestock for their livelihoods. The continued burden of brucellosis in these regions is primarily attributed to limited resources and the absence of organized, coordinated prevention and control efforts [22]. Brucellosis remains a widespread problem in the Mediterranean region, Western Asia, parts of Africa, and Latin America [23]. Underreporting and frequent misdiagnosis due to the disease’s clinical similarities with other infections have further delayed the implementation of effective control programs [24]. The epidemiology of brucellosis is highly complex, varying significantly across different agro-ecological zones. The disease continues to show high incidence and prevalence among animals in Africa, the Mediterranean, the Middle East, the Arabian Peninsula, the Indian subcontinent, and regions of Mexico, Central, and South America. This persistence is likely linked to the lack of established control or eradication strategies in these areas [25] (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Map of Brucellosis outbreaks in livestock - WAHIS 2014 [26].

Possible risk factors for infection: Host risk factors: All animals are generally susceptible to brucellosis, and to date, no specific breed has shown resistance to the disease. Host factors such as age, sex, and reproductive status significantly influence susceptibility. While Brucella infection can occur at any age, it is most commonly observed in sexually mature animals, particularly during pregnancy [27]. Infection often occurs around parturition, when exposure to contaminated materials is highest. The seroprevalence of brucellosis tends to increase with age and sexual maturity, while it remains relatively low in younger animals [28]. This lower prevalence in young stock may be due to latent infection, where the organism remains in regional lymph nodes without triggering detectable antibody production until the animal conceives. During pregnancy, secretion of erythritol, a sugar alcohol found in fetal tissues, promotes Brucella growth and leads to immune detection [29]. Sex hormones and erythritol present in the male reproductive organs and in the allantoic fluid of pregnant females further enhance the proliferation of the bacteria, which explains the increased susceptibility with age and reproductive activity [30]. Infected cows that abort typically develop immunity but may remain carriers, continuing to shed large quantities of Brucella in fetal fluids during subsequent pregnancies [31].

Pathogen risk factors: Brucella is a facultative intracellular organism capable of multiplication and survival within the host phagocytic cells. The organisms are phagocytized by polymorpho nuclear leucocytes in which some survive and multiply. The organism is able to survive with in macrophages because; it has the ability to survive phagolysosome. The bacterium possesses an unconventional non endotoxin lipopolysacharide which confers resistance to antimicrobial attacks and modulates the host immune response. These properties make lipopolysacharide an important virulence factor for Brucella survival and replication [32].

Climatic and environmental factors: Survivability of the organism in the environment plays a great role in the epidemiology and transmission of the disease. Brucella may retain for several months in water, aborted fetuses, fetal membranes, feces, liquid manure, wool, hay, buildings, equipment and clothes. It is also able to withstand drying and will persist in dust and soil. Temperature, humidity and pH influence the organism’s ability to survive in the environment. Brucella is sensitive to direct sunlight, disinfectant and pasteurization [8,33].

Occupational risk factor: Workers handling Brucella cultures in laboratories are at high risk of acquiring brucellosis through aerosolizing due to inadequate laboratory procedures. In addition to this, abattoir workers, farmers, veterinarians and others who work with animals and consume their products are acquiring the infection [34]. Though muscle tissue of animals contains low concentrations of Brucella organisms, consumption of undercooked meat can transmit brucellosis, which may be due to contamination with blood and other potential secretions. But, Brucella has higher concentration in liver, kidney, spleen, udder and testis and consumption of these organs and tissues undercooked has very high risk. Inhalation of contaminated dust and infected animal fluids are also the main source of infection, particularly in clinics, laboratories and abattoirs [35].

Management risk factors: The unregulated movement of animals from brucellosis infected herds to free ones is the major means for the spread of the disease. Replacement or purchasing from an infected source is also potential for disease introduction to disease free herd. Improper management of reproductive tract excretion and abortion materials is the main source of infection. In lactating cows, if managed carelessly, the milk including colostrum is an important source of infection, and bacteria are excreted in milk throughout the lactation period. A contaminated environment or equipment used for milking or artificial insemination are further sources of infection too [36].

Mode of Transmission and Route of Infection

The gastrointestinal tract is the primary route of Brucella transmission, typically following the ingestion of contaminated pasture, feed, fodder, or water. Animals become infected through ingestion or inhalation of the bacteria from sources such as aborted fetuses, fetal fluids, and vaginal discharges contaminating the environment [36]. The disease can also spread between herds via infected animals, including through contact with wildlife that may carry the infection into brucellosis-free herds.

Aborted materials are a major source of Brucella transmission to both animals and humans, with large numbers of bacteria shed during abortion or parturition [37]. Horizontal transmission can also occur through contaminated feed or water, skin abrasions, conjunctival exposure, inhalation, udder contamination during milking, or licking of infected discharges or retained fetal membranes.

Venereal transmission has been reported, particularly for B. ovis, B. suis, and B. canis. Although B. abortus and B. melitensis can be present in semen, sexual transmission is considered rare for these species [38].

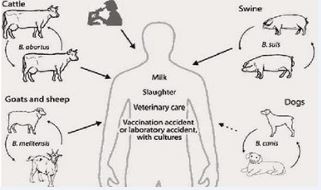

In humans, infection commonly occurs through the consumption of unpasteurized dairy products, raw blood, or undercooked meat especially organs like the liver, kidney, and spleen. It can also be contracted through direct contact with infected materials during or after parturition, making it an occupational hazard for individuals in high- risk professions [39] (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Transmission of Brucella [40].

Pathogenesis

Brucella bacteria exhibit a strong preference for certain tissues, particularly the pregnant uterus, udder, testes, accessory male sex glands, lymph nodes, joint capsules, and bursae. Following initial entry into the body, the bacteria primarily localize in the lymph nodes. Brucella species have the ability to invade host epithelial cells, often entering through M cells in the intestinal lining, after which they become sequestered within monocytes and macrophages of the reticuloendothelial system (RES), including the lymph nodes, liver, spleen, and bone marrow [41]. Once inside phagocytic cells, the bacteria migrate via the lymphatic system to regional lymph nodes. There, Brucella infection can result in cell lysis and hemorrhaging of the lymph nodes upon exposure [42].

Due to vascular damage, some bacteria escape into the bloodstream, leading to bacteremia and systemic dissemination. In pregnant animals, B. abortus preferentially colonizes and rapidly multiplies in the chorionic trophoblasts of the developing fetus. This colonization leads to necrosis of the fetal membranes and facilitates transmission of the bacteria to the fetus. The cumulative result of trophoblast infection and placental colonization is abortion, typically occurring in the final trimester of gestation [43].

The bacteria’s affinity for the reproductive organs in pregnant animals is linked to specific, yet not fully identified, factors found in the gravid uterus, collectively referred to as allantoic fluid factors. One such factor,

erythritol, a four-carbon sugar alcohol, has been identified as promoting the growth of Brucella. Erythritol levels rise in the placenta and fetal fluids starting around the fifth month of pregnancy [42].

The organism’s preferential replication in the extraplacentomal areas, particularly within the trophoblasts of the chorioallantoic membrane, leads to cellular rupture and ulceration of the fetal membranes. The resulting damage to placental tissue, along with fetal infection and distress, triggers maternal hormonal changes that induce abortion. This generally occurs during the final trimester, with the incubation period inversely related to the developmental stage of the fetus at the time of infection [44].

Clinical Signs

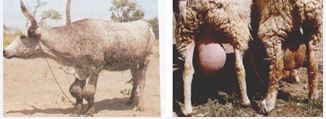

Clinical signs in animals: In animals, brucellosis can persist as a latent infection for several years, with clinical signs typically associated with the reproductive system. In females, the disease often presents as abortion during the third trimester, weak newborns, retained placenta, endometritis, and reduced milk production (Figure 4). In highly susceptible, unvaccinated pregnant animals, abortion after the fifth month of gestation is a hallmark sign. Although animals that abort due to brucellosis usually develop immunity, they often remain carriers and may continue to shed large numbers of Brucella organisms in fetal fluids during subsequent calvings [45].

Figure 3 Hygromas on leg joints, swollen testes and udder.

Figure 4 Clinical signs of brucellosis in small ruminants.

Abortion accompanied by retained placenta can lead to metritis, extended calving intervals, and potentially permanent infertility. In males, brucellosis may cause orchitis, epididymitis, and infertility. Chronic cases may present with polyarthritis, hygromas, and, in some instances, vaginitis. Aborted fetuses frequently exhibit blood-tinged fluid accumulation in body cavities along with an enlarged spleen and liver. Additionally, a mild interstitial inflammatory response in the mammary gland may occur, facilitating the shedding of bacteria through milk. In chronic infections, enlargement of the epididymis is common. Hygromas, particularly around leg joints in large animals, and swelling of the testes or udder in small ruminants (Figure 3), are frequent clinical signs observed in tropical regions [46-48].

Symptoms of human brucellosis: The most common symptoms of brucellosis include undulant fever in which the temperature can vary from 37.8°C in the morning to 40°C in the afternoon; night sweets and weakness. Common symptoms also include insomnia, anorexia, headache, constipation, sexual impotence, nervousness, encephalitis, arthritis, endocarditis, orchitis and depression [21]. Spontaneous abortion seen mostly in the first and second trimesters of pregnancy in pregnant women infected with Brucella. Lack of appropriate therapy during the acute phases may result in localization of Brucella in various tissues and organs and lead to sub-acute or chronic disease, which is very hard to treat [49].

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of brucellosis always requires laboratory confirmation. It is made possible by direct demonstration of the causal organism using microscopic examination, culture methods, animal inoculation (identification of the agent), directly demonstration of antibodies using serological techniques and molecular methods [50].

Microscopic examination and culture methods: Specimen of fetal stomach, lung, liver, placenta, cotyledon and vaginal discharges are stained with Gram stain and modified Ziehl Nelson stains. Brucella appears as small red-colored, coccobacili in clumps. Blood or bone marrow samples can be taken cultured in 5-10% blood agar is used. To check up bacterial and fungal contamination; Brucella selective media are often used [51]. The selective media are nutritive media, blood agar based with 5% sero negative equine or bovine serum. On primary isolation it usually requires the addition of 5-10% carbon dioxide and takes 3-5 days incubation at 37°C for visible colonies to appear [52].

Animal inoculation: Lab animals such as guinea pigs are intramuscularly inoculated 0.5-1ml of suspected tissue homogenate and sacrificed at three- and six-weeks post inoculation and serum is taken along with spleen and other abnormal tissue for serology and bacteriological examination [53].

Serological diagnosis: Body fluid such as serum, uterine discharge, vaginal mucus, and milk or semen plasma from suspected cattle may contain different quantities of antibodies of the IgM, IgG1, IgG2 and IgA types directed against Brucella [54].

Milk ring test: It is cheap, easy, simple and quick to perform. It detects lacteal antiBrucella IgM and fat globules from milk and form red ring in positive case. However, it tests false positive when milk that contains colostrums, milk at the end of the lactation period, milk from cows suffering from abnormal disorder or mastitis. Milk that contain low concentration of lacteal IgM, IgA or lack the fat clustering factors, tests false negative. Because lacteal antibodies rapidly decline after abortion or parturition, the reliability of milk ring test using 1ml milk to detect Brucella antibodies in individual cattle or intact milk is strongly reduced [55]. Although the milk ring test performed with 8ml milk, it improved the detection of brucellosis in tank milk. It may test false positive when races of colostrums are present in tank milk [21].

Rose Bengal plate test (RBPT): Rose Bengal Plate Test is simple, rapid test used for screening animal brucellosis. It is used to screen sera for Brucella antibodies. The test detects specific antibodies of the IgM and IgG type. Although the low PH (3.6) of the antigen enhances the specificity of the test and temperature of the antigen and the ambient temperature at which the reaction takes place may influence the sensitivity and specificity of the test [56].

Complement fixation test (CFT): The Complement Fixation Test (CFT) is known for its high specificity; however, it requires well-equipped laboratory facilities and personnel with advanced technical training. The test primarily detects IgG1 antibodies, with less sensitivity to IgM antibodies. It is considered the most dependable diagnostic tool currently used for testing individual animals. Notably, CFT is relatively unaffected by antibodies produced as a result of vaccination with Brucella strain 19 [57].

Despite its complexity, CFT is widely utilized and recognized as a confirmatory test. Accurate performance of the test depends on precise titration and proper maintenance of reagents, which necessitates skilled laboratory staff. Although various modifications of the

CFT exist, the microtiter format is the most practical and commonly applied version [58].

The test can be conducted using either warm or cold fixation during the incubation of serum, antigen, and complement—typically 37°C for 30 minutes or 4°C for 14–18 hours. Several factors influence the choice of fixation method. For example, cold fixation tends to reveal anti-complementary activity more clearly in poor-quality serum samples, whereas warm fixation at 37°C may lead to more frequent and intense prozone effects, requiring multiple dilutions to be tested for each sample [59].

ELISA test: The indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is a widely used serological method for determining the prevalence of brucellosis in epidemiological surveys. This test offers high sensitivity and specificity while requiring minimal equipment, as it is typically available in ready-to-use kit form. Its ease of use and reliability make it particularly well-suited for smaller laboratories, and it has become an important diagnostic tool for a broad range of animal and human diseases [50].

Although ELISA can, in principle, be applied to serum samples from various animal species as well as humans, results may vary between laboratories due to differences in methodologies. Standardization of protocols remains an ongoing challenge, and discrepancies in outcomes can occur as a result. For screening purposes, the test is generally performed using a single serum dilution. It is also worth noting that while ELISA offers slightly higher specificity than the Rose Bengal Plate Test (RBPT) or Complement Fixation Test (CFT), the improvement is only marginal [56].

Molecular methods

Polymerase Chain Reaction: Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays can be used to detect Brucella DNA in pure cultures and in clinical specimens, i.e. serum, whole- blood and urine samples, various tissues, cerebrospinal, synovial or pleural fluid, and pus [60]. Direct detection of Brucella DNA in brucellosis patients is a challenge because of the small number of bacteria present in clinical samples and inhibitory effects arising from matrix components. Basic sample preparation methods should minimize inhibitory effects and concentrate the bacterial DNA template [61].

Significance of the Disease

Economic Significance: Brucellosis remains endemic in many low-income countries across sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, where it poses significant economic

challenges not only in agriculture and public health but also in broader socio-economic development. The economic burden of the disease in these regions is compounded by limited resources, weak veterinary infrastructure, and the high prevalence of other infectious diseases. Unlike high-income countries, where brucellosis control and eradication programs have seen notable success, simply replicating these approaches is unlikely to be effective in low-income settings. This is largely due to the far greater infectious disease burden estimated to be at least ten times higher in low-income countries [62].

A comprehensive assessment of the economic dimensions of brucellosis in Africa and Asia typically involves three major components. First, it outlines a general framework for evaluating the economic burden of disease and the potential impact of control strategies. Second, it provides a systematic review of available studies estimating the burden of brucellosis in animals, humans, and in joint animal-human contexts. Third, where data is available, it presents estimates of various costs associated with the disease both in terms of illness and control interventions. This final component also discusses tools and methodologies relevant for evaluating brucellosis control programs in low- and middle-income countries [63].

The detection of brucellosis in livestock herds, flocks, or at regional or national levels often triggers international veterinary trade restrictions, leading to significant economic losses. These losses, alongside the disease’s public health implications, are the primary drivers behind the establishment of control and eradication programs targeting brucellosis, especially in cattle [64].

In Ethiopia, however, data on the economic losses specifically attributable to brucellosis across different livestock production systems remain limited. One of the few documented studies by Tariku [65], reported an estimated annual loss of 88,941.96 Ethiopian Birr (equivalent to approximately USD 5,231) among 193 cattle at Chaffa State Farm in Wollo. These losses, recorded between 1987 and 1993, were mainly due to reduced milk yield and abortion events resulting from brucellosis infections.

Public Health Significance

Brucella species such as Brucella abortus, B. melitensis, and B. suis are recognized as highly pathogenic to humans. Brucellosis remains the most widespread zoonotic disease globally, with over 500,000 new human cases reported annually [66]. However, the true burden is likely much higher due to underreporting and undiagnosed infections [67]. Despite its endemic nature and significant zoonotic

potential in many parts of the world, brucellosis is often neglected in public health discussions [68].

The prevalence of human brucellosis varies significantly across regions, influenced by factors such as personal and environmental hygiene standards, animal husbandry practices, the specific Brucella species involved, and local food processing methods [21]. According to the Brucellosis 2003 International Research Conference, an estimated 500,000 human infections occur worldwide each year. Incidence rates vary from less than one case per 100,000 individuals in countries like the UK, USA, and Australia, to 20–30 cases per 100,000 in southern European nations such as Greece and Spain, and over 70 cases per 100,000 in Middle Eastern countries including Kuwait and Saudi Arabia [69].

Most human brucellosis cases are attributed to B. melitensis, B. abortus, and B. suis, in that order of prevalence. In recent years, novel and atypical Brucella strains have also emerged as subjects of investigation [67].

Compared to research on animal brucellosis, studies on human brucellosis in Ethiopia remain limited, particularly concerning the identification of risk factors for human infection. For example, a study involving 56 patients with fever of unknown origin found that 2 individuals (3.6%) tested positive for B. abortus antibodies using the Rose Bengal Plate Test (RBPT) and Complement Fixation Test (CFT) [70]. Another study by Pal et al. [64], in traditional pastoralist communities found that among febrile patients, 34.1% in Borena, 29.4% in Hammer, and 3% in Metema tested positive using the Brucella IgM/IgG lateral flow assay.

Research targeting high-risk occupational groups including farmers, veterinary workers, meat inspectors, and artificial insemination technicians has revealed notable seroprevalence rates: 5.30% in the Amhara Regional State [71], 3.78% in the Sidama Zone [72], and 4.8% in Addis Ababa [73]. Differences in seroprevalence rates among studies may be attributed to varying dietary practices, particularly raw milk consumption, as well as differences in the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic tests used [9].

Human infection typically occurs through the consumption of unpasteurized dairy products such as milk and cheese, direct contact with infected animals, or handling of Brucella-contaminated materials in laboratory settings. Transmission can also occur via exposure to the skin or mucous membranes during animal parturition or abortion, especially among those who consume raw milk or engage in risky animal handling practices [9].

In South Sudan, several traditional practices and risk factors contribute to the spread of brucellosis among livestock and humans [74]. A key contributor is the pastoralist tradition of grouping multiple herds in cattle camps, resulting in frequent and close interactions between humans and animals. Poor awareness regarding the disease further compounds its persistence in livestock populations, subsequently posing a threat to human health [75]. Risk-enhancing practices such as vulval blowing during milking to stimulate letdown and direct udder-to- mouth consumption of raw milk have also been identified as potential transmission routes [74]. Notably, consuming raw milk has been significantly associated with brucellosis infection, whereas boiling milk has been shown to be a protective practice. Therefore, public health education promoting the benefits of boiling milk before consumption is essential in mitigating the spread of brucellosis.

Treatment

An effective treatment for animals with brucellosis is not known to date [76]. The treatment of brucellosis in the cow has generally been unsuccessful because of the intracellular sequestration of the organisms in lymph nodes, the mammary gland, and reproductive organs and the bacteria are facultative intracellular which survive and multiply within the cells [19]. Generally, treatment of infected livestock is not attempted because of the high treatment failure rate, cost, and potential problems related to maintaining infected animals in the face of ongoing eradication programs [77]. Man can be treated with antibiotics (doxicyclin with rifampicin), however, relapses are impossible [78].

Prevention and Control

Prevention, control and eradication of brucellosis are a major challenge for public health programmes. Although controlled or eradicated in a number of developed countries, re-introduction of brucellosis remains a constant threat, while in others, especially in the developing world, this disease continues to exert its devastating impact perpetuating poverty [21]. The strategies for preventing brucellosis have to be adapted to the animal production system [64]. The successful prevention of this disease, which is so difficult in cattle production in the tropics, requires that, as far as possible, all available steps taken to combat it [19].

Vaccination: The WHO has long been involved in brucellosis surveillance and control, including research and development of vaccines to prevent animal brucellosis [79]. Systematic vaccination of animals is recommended where the prevalence is greater than 5% [21]. Vaccine

increases individual resistance to systemic infection, and in infected animals decreases the probability of placental infection, abortion and massive shedding of infectious organisms [80].

Test and slaughter: It involves recognition of all animals which have responded immunologically to a Brucella infection and subsequent culling of the reactors. According to Musa and Roba [81], this method could be achieved when the rate of infection is reduced to an acceptable level (about 1-2%). Part of the scheme has to be a careful control of all animals which will be newly added to the herd as well as a production system which prevents contact with infected neighboring farms and/or contaminated feed or pasture.

Pasteurization: The most rational approach for preventing human brucellosis is control and eradication of the infection in animal reservoirs. Brucella is inactivated by pasteurization and its survival outside the host is largely dependent on environmental conditions. The pathogen may survive in aborted fetus in the shade for up to eight months, for two to three months in wet soil, one to two months in dry soil, three to four months in faeces, and eight months in liquid manure tanks. Bacterial survival is prolonged at low temperatures and organisms will remain viable for many years in frozen carcass [82]. Pasteurization of dairy products is an important safety measure where this disease is endemic. Unpasteurized dairy products and raw or undercooked animal products (including bone marrow) should not be consumed [83].

Hygienic Prophylaxis: Experience shows that vaccination alone cannot bring about the eradication of the disease [21]. From the epidemiology of the disease, important steps were derived at an early stage as hygienic prophylactic measures. These include the isolation of calving animals’ in separate calving pens which are subsequently disinfected with 2.5 % formalin, wet and well- grassed calving camps should be avoided, and vehicles used for transporting infected animals should be disinfected after use [84], aborted fetuses, placentas, and uterine discharges must be disposed of, preferably by incineration, test all cattle, horses, and pigs brought to the farm, isolate for 30 days, and retest, cows, which are in advanced pregnancy, should be kept in isolation until after parturition, replacement stock should be purchased from herd free of brucellosis [19].

Recent Status of Small Ruminant Brucellosis in Ethiopia

Small ruminant brucellosis is endemic and widely distributed in Ethiopia, which has been causing high

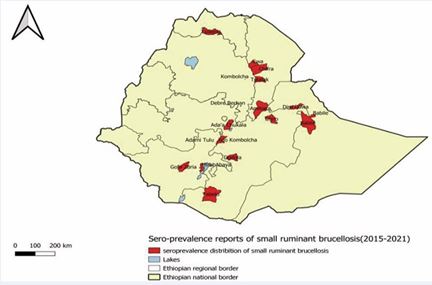

economic losses as well as becoming a serious public health threat [85]. The distribution or prevalence of small prevalence of brucellosis in Ethiopia is varied from place to place and time to time may be due to differences in animal production and management system, community living standard and awareness level as well as agro ecological conditions of those study places (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Blowing through the vulva to let down the milk and direct sucking of raw milk from the cattle camps; Source: [74].

Different seroprevalence study reports which have been conducted since 2015 shows the disease is endemic in Ethiopia [37]. This seropositive prevalence may be due to natural infection because of no brucellosis prevention and control vaccination history in Ethiopia [86]. Recent studies conducted across Ethiopia by Muhidin et al. [87] in Berbere district of Bale zone, Wubay et al. [11] in Chiro and Burka Dhintu districts of West Hararghe zone, Hussen et al. [12] in Karohey zone of Somali regional state, Edao et al. [86] in Borana zone and Teshome et al. [88] in Yabello district of Borana zone revealed brucellosis seroprevalence of 2.97%, 6.50%, 6.40%, 8% and 7.44%, respectively. Recently, a research reported an overall animal level prevalence of 6.5% and 2.9%, tested by RBPT and CFT respectively in Bale Zone, Oromia region [89]. A study with an overall animal level prevalence of 6.5% and 2.9%, tested by RBPT and CFT respectively in untouched areas of Oromia region indicates how the disease has wider spread prevalence in the country [90] (Table 1).

|

Region |

Specific study area |

Prevalence (%) |

Year of publication |

Reference |

|

Afar |

Dubti |

6.7 |

2025 |

Dubie et al.[91] |

|

Oromia |

Chiro and Burka districts |

6.5 |

2024 |

Wubay et al. [11] |

|

Somali |

3 districts |

1.23 |

2023 |

Hussen et al. [12] |

|

Somali |

Korahey zone |

6.4 |

2023 |

Hussen et al. [12] |

|

South Ethiopia |

SouthOmo |

1.65 |

2023 |

Getachew et al. [92] |

|

Oromia |

Elweye, Moyale and Yabello districts |

17.36 |

2022 |

Teshome et al. [88] |

|

Afar |

In 7 districts |

8.9 |

2021 |

Tschopp et al. [89] |

|

Somali |

In 6 districts |

6.6 |

2021 |

Tschopp et al. [89] |

|

Oromia |

Bale |

22 |

2021 |

Adem et al. [90] |

|

Oromia |

Chiro |

0.24 |

2021 |

Geletu et al. [2] |

|

SNNPR |

S/Omo |

21 |

2020 |

Dima et al. [93] |

|

Oromia |

Borena |

3.2 |

2020 |

Edao et al. [86] |

|

Oromia |

Borena |

8.8 |

2020 |

Zewdie, [94] |

|

Harare |

Babile |

0.78 |

2019 |

Atlaw & Girma, [95] |

|

Oromia |

Borena |

8.1 |

2019 |

Demena, [96] |

|

SNNPR |

Nechisar |

12.8 |

2018 |

Chaka et al. [97] |

|

D/Dawa |

D/Dawa |

2.6 |

2018 |

Teshome et al. [98] |

|

Amhara |

S/W &N/S |

4.89 |

2018 |

Addis et al. [99] |

|

Tigrai |

Tselemt |

1.79 |

2017 |

Kelkay et al. [100] |

|

SNNPR |

Meirab Abaya |

5.1 |

2017 |

Dulo, [101] |

|

Somali |

Jigiga/Gursm |

1.37 |

2017 |

Mohammed et al, [48] |

Table 1: Small ruminant Brucellosis sero-prevalence reports in Ethiopia (2017-2025).

Key: D/Dawa (Dire-Dawa), D.Z & M.EA (Debre -Zeit and Mojo Export Abattoirs), S/W &N/S (South Wolo and North Shewa), S/Omo (South Omo).

Figure 6 Distribution of small ruminant brucellosis (Sero-prevalence 2015-2021) [102]

The observed disparity in brucellosis prevalence among different regions of Ethiopia could also be attributed to various factors including differences in testing protocols, age difference, sex, pregnancy status, geographical difference, animal management practices, reproductive diseases, herd size, sample size, and the serological tests employed that would further accentuate these variations [76].

Furthermore, the distribution of small ruminant brucellosis was described on the following map (Figure 6)

Knowledge of Respondents about Brucellosis

Several researchers have assessed respondents’understanding of brucellosis using structured questionnaire surveys. Their findings consistently revealed a substantial knowledge gap regarding the disease, particularly in areas such as its causes, modes of transmission, symptoms, prevention methods, and potential public health implications which indicates a need for increased awareness and targeted educational interventions to bridge the existing knowledge deficit. The study conducted by Wubay et al. [11], concluded that, the community in the study area had inadequate knowledge regarding brucellosis which is in consistent with other

researchers result. According to his finding, nearly three quarters (74.0 %) of the study respondents stated that they had provided assistance to their ewes and does during the time of giving birth without using protective equipment and majority of them (82.4 %) consume raw milk.

With respect to knowledge about zoonotic disease risks, the majority of individuals demonstrated a lack of awareness that brucellosis can be transmitted from animals to humans. Most respondents were unaware of the zoonotic nature of the disease and did not recognize the potential health risks it poses to humans. Furthermore

a significant portion of the population lacked information about effective prevention and control measures for brucellosis in both animals and humans. This highlights a critical gap in public health education and the urgent need for awareness campaigns to improve understanding and promote safer practices among communities at risk [86].

Knowledge about the disease and preventive flock management practices have previously been identified as the most important factors needed for minimizing the disease risk in animals. This combination of high-risk exposure and poor awareness underscores the urgent need for targeted education programs and training on safe animal handling practices and the importance of using PPE to protect both human and animal health [103].

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The review of various recent studies on small ruminant brucellosis reveals the presence of the disease in sheep and goats across different regions of the country, with varying seroprevalence rates. The incidence of the disease differs by region and is influenced by factors related to the animals, their environment, and management practices. This variation highlights the need for tailored, region-specific control strategies and enhanced disease surveillance. According to the review, the seroprevalence of brucellosis in small ruminants ranged from a minimum of 0.24% to a maximum of 17.36%, indicating considerable differences in the risk factors associated with the disease across the country. Based on the above conclusion, the following recommendations were forwarded :

- Enhance routine surveillance and diagnostic capabilities to accurately detect and monitor brucellosis cases, enabling early response and containment.

- Where feasible, initiating vaccination programs is recommended in small ruminants, particularly in areas with high sero-prevalence, to reduce infection rates and improve herd immunity

REFERENCES

- Abro Z, Kimathi E, De Groote H, Tefera T, Sevgan S, Niassy S, et al. Socioeconomic and health impacts of fall armyworm in Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2021; 16: e0257736.

- Geletu US, Usmael MA, Mummed YY. Seroprevalence and risk factors of small ruminant brucellosis in West Hararghe Zone of Oromia Regional State, Eastern Ethiopia. Vet Med Int. 2021; 2021: 6671554.

- Kiros A, Asgedom H, Abdi RD. A review on bovine brucellosis: Epidemiology, diagnosis and control options. ARC J Animal Vet Sci (AJAVS). 2016; 2: 8-21.

- Sibhat B, Tessema TS, Nile E, Asmare K. Brucellosis in Ethiopia: A comprehensive review of literature from the year 2000–2020 and the way forward. Transbound emerg dis. 2022; 69: e1231-e1252.

- Shoukat S, Wani H, Ali U, Para PA, Ara S, Ganguly S. Brucellosis: a current review update on zoonosis. 2017; 19: 61-69.

- Murphy SC, Negron ME, Pieracci EG, Deressa A, Bekele W, Regassa F, et al. One Health collaborations for zoonotic disease control in Ethiopia. Rev Sci Tech. 2019; 38: 51-60.

- Foster G, Osterman BS, Godfroid J, Jacques I, Cloeckaert A. Brucella ceti sp. nov. and Brucella pinnipedialis sp. nov. for Brucella strains with cetaceans and seals as their preferred hosts. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007; 57: 2688-2693.

- Coelho AC, Díez JG, Coelho AM. Risk factors for brucella spp. Domestic and wild animals. 2015: 1-32.

- Ferede Y, Mengesha D, Mekonen G. Study on the seroprevalence of small ruminant brucellosis in and around Bahir Dar, North West Ethiopia. Ethiopia Vet J. 2011; 15.

- ABERA A. ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY, COLLEGE OF VETERINARY MEDICINE AND AGRICULTURE, DEPARTMENT OF VETERINARY MICROBIOLOGY, IMMUNOLOGY AND PUBLIC HEALTH. 2018.

- Wubaye AM, Mitiku S, Lataa DT, Ambaw YG, Mekonen MT, Kallu SA. Seroprevalence of small ruminant brucellosis and owners knowledge, attitude and practices in Chiro and Burka Dhintu Districts, West Hararghe, Ethiopia. Heliyon. 2024; 10: e37708.

- Hussen AM, Alemu F, Hasan Hussen A, Mohamed AH, Gebremeskel HF. Herd and animal level seroprevalence and associated risk factors of small ruminant brucellosis in the Korahey zone, Somali regional state, eastern Ethiopia. Front Vet Sci. 2023; 10: 1236494.

- Tsegay A, Tuli G, Kassa T, Kebede N. Seroprevalence and risk factors of Brucellosis in small ruminants slaughtered at Debre Ziet and Modjo export abattoirs, Ethiopia. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2015; 9: 373-380.

- Tekle M, Legesse M, Edao BM, Ameni G, Mamo G. Isolation and identification of Brucella melitensis using bacteriological and molecular tools from aborted goats in the Afar region of north- eastern Ethiopia. BMC microbiology. 2019; 19: 108.

- Ashenafi F, Teshale S, Ejeta G, Fikru R, Laikemariam Y. Distribution of brucellosis among small ruminants in the pastoral region of Afar, eastern Ethiopia. Rev Sci Tech. 2007; 26: 731-739.

- Teka D, Tadesse B, Kinfe G, Denberga Y. Sero-prevalence of bovine brucellosis and its associated risk factors in Becho District, South West Shewa, Oromia regional state. ARC J Animal Vet Sci. 2019; 5: 35-45.

- Banai M, Corbel M. Taxonomy of Brucella. Open Vet Sci J. 2010; 4: 85-101.

- Seria W, Tadese YD, Shumi E. A review on brucellosis in smallruminants. Am J Zool. 2020; 3: 17-25.

- Getahun TK, Urge B, Mamo G. Seroprevalence of Brucellosis in dairy animals and their owners in selected sites, Central Highlands of Ethiopia. Int J Tropical Vet Biomed Res. 2023; 7: 23-39.

- Ambika N. Studies on stress susceptibility growth kinetics andstability of Brucella abortus S19 per (Doctoral dissertation). 2023.

- Mitiku W, Desa G. Review of bovine brucellosis and its public healthsignificance. Healthcare Review. 2020; 1: 16-33.

- Khatibi M, Abdulaliyev G, Azimov A, Ismailova R, Ibrahimov S, Shikhiyev M, et al. Working towards development of a sustainable brucellosis control programme, the Azerbaijan example. Res Vet Sci. 2021; 137: 252-261.

- Ducrotoy MJ, Bertu WJ, Ocholi RA, Gusi AM, Bryssinckx W, Welburn S, et al. Brucellosis as an emerging threat in developing economies:lessons from Nigeria. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2014; 8:e3008.

- Aworh MK, Okolocha E, Kwaga J, Fasina F, Lazarus D, Suleman I, et al. Human brucellosis: seroprevalence and associated exposure factors among abattoir workers in Abuja, Nigeria-2011. Pan Afr Med J. 2013; 16: 103.

- Nicoletti P. Brucellosis: past, present and future. Prilozi. 2010; 31:21-32.

- Hull NC, Schumaker BA. Comparisons of brucellosis between humanand veterinary medicine. Infect ecol epidemiol. 2018; 8: 1500846.

- Gul ST, Khan A, Rizvi F, Hussain I. Sero-prevalence of brucellosis in food animals in the Punjab, Pakistan. 2014; 34: 454- 458.

- Negash E, Shimelis S, Beyene D. Seroprevalence of small ruminant brucellosis and its public health awareness in selected sites of Dire Dawa region, Eastern Ethiopia. J Vet Med Anim Health. 2012; 4: 61- 66.

- Bile MM, Motbynor A, Getahun D. SEROPREVALENCE OF BRUCELLOSIS IN SMALL RUMINANTS, ITS RISK FACTORS, KNOWLEDGE, ATTITUDE AND PRACTICE TOWARDS COMMUNITIESIN GARAWE DISTRICT, SOMALIA (Doctoral dissertation, HaramayaUniversity).

- Megersa B, Biffa D, Abunna F, Regassa A, Godfroid J, Skjerve E. Seroepidemiological study of livestock brucellosis in a pastoral region. Epidemiol Infect. 2012; 140: 887-896.

- Al-Hamada A. An epidemiological study of the impact of Toxoplasma gondii and Brucella melitensis on reproduction in sheep and goats in Dohuk Province, Iraq (Doctoral dissertation, Murdoch University). 2021.

- Stranahan LW, Arenas-Gamboa AM. When the going gets rough: The significance of Brucella lipopolysaccharide phenotype in host– pathogen interactions. Front Microbiol. 2021; 12: 713157.

- Beruktayet W, Mersha C. Review of cattle brucellosis in Ethiopia. Acad J Anim Dis. 2016; 5: 28-39.

- Karadzinska-Bislimovska J, Minov J, Mijakoski D, Stoleski S, TodorovS. Brucellosis as an occupational disease in the Republic of Macedonia. 2010; 3: 251-256.

- Zewdie W. Review on Bovine, Small ruminant and Human Brucellosisin Ethiopia. J Vet Med Res. 2018; 5: 1157.

- Madzingira O. Epidemiology and Molecular Confirmation of Brucella Spp. in Cattle in Namibia (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pretoria (South Africa)). 2021.

- Bedore B, Mustefa M. Review on Epidemiology and Economic Impact of Small Ruminant Brucellosis in Ethiopian Perspective. 2019; 4: 77- 86.

- Pal M, Kerorsa GB, Desalegn C, Kandi V. Human and animal brucellosis: a comprehensive review of biology, pathogenesis, epidemiology, risk factors, clinical signs, laboratory diagnosis. Am J Infect Dis. 2020; 8: 118-126.

- Abera M. A Review on Bovine Brucellosis and Its Public HealthSignificance in Ethiopia. J Vet Med Sci. 2024; 1.

- Gadaga B. A survey of brucellosis and bovine tuberculosis in humans at a wildlife/domestic animal/human interface. 2013.

- Paixao TA, Roux CM, den Hartigh AB, Sankaran-Walters S, Dandekar S, Santos RL, et al. Establishment of systemic Brucella melitensis infection through the digestive tract requires urease, the type IV secretion system, and lipopolysaccharide O antigen. Infect immun. 2009; 77: 4197-4208.

- Neta AV, Mol JP, Xavier MN, Paixão TA, Lage AP, Santos RL.Pathogenesis of bovine brucellosis. Vet J. 2010; 184: 146-155.

- Taylor D, Upadhyay UD, Fjerstad M, Battistelli MF, Weitz TA, Paul ME. Standardizing the classification of abortion incidents: the Procedural Abortion Incident Reporting and Surveillance (PAIRS) Framework. Contraception. 2017; 96: 1-13.

- Borel N, Frey CF, Gottstein B, Hilbe M, Pospischil A, Franzoso FD, et al. Laboratory diagnosis of ruminant abortion in Europe. Vet J. 2014; 200: 218-229.

- Megid J, Mathias LA, Robles C. Clinical manifestations of brucellosis in domestic animals and humans. Open Vet Sci J. 2010; 4: 119-126.

- Yami A, Sheep E, Merkel RC. Sheep and goat production handbook for Ethiopia. 2008.

- Weldegebriall B. Assessment of major reproductive problems of dairy cattle in selected sites of central Zone of Tigrai Region, northern Ethiopia (Doctoral dissertation, Mekelle University). 2015.

- Mohammed M, Mindaye S, Hailemariam Z, Tamerat N, Muktar Y. Sero- prevalence of small ruminant brucellosis in three selected districts of Somali region, eastern Ethiopia. J Vet Sci Animal Husb. 2017; 5: 1-6.

- Bosilkovski M, Krteva L, Dimzova M, Kondova I. Brucellosis in 418 patients from the Balkan Peninsula: exposure-related differences in clinical manifestations, laboratory test results, and therapy outcome. Int j infect dis. 2007; 11: 342-347.

- Kaur G. Development and evaluation of recombinant antigen based enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (Elisa) for serodiagnosis of brucellosis (Doctoral dissertation, Guru Angad Dev Veterinary and Animal Sciences University). 2014.

- De Miguel MJ, Marín CM, Muñoz PM, Dieste L, Grilló MJ, Blasco JM. Development of a selective culture medium for primary isolation of the main Brucella species. J Clin Microbiol. 2011; 49: 1458-1463.

- Ledwaba MB, Matle I, Van Heerden H, Ndumnego OC, Gelaw AK. Investigating selective media for optimal isolation of Brucella spp. in South Africa. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2020; 87: 1-9.

- Pappas G, Akritidis N, Tsianos E. Effective treatments in the management of brucellosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2005; 6: 201-209.

- Kaltungo BY, Saidu SN, Sackey AK, Kazeem HM. A review on diagnostictechniques for brucellosis. Afr J Biotechnol. 2014; 13: 1-10.

- Matekwe N. Seroprevalence of Brucella abortus in cattle at communal diptanks in the Mnisi area, Mpumalanga, South Africa (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pretoria). 2011.

- Legesse A, Mekuriaw A, Gelaye E, Abayneh T, Getachew B, Weldemedhin W, et al. Comparative evaluation of RBPT, I-ELISA, and CFT for the diagnosis of brucellosis and PCR detection of Brucella species from Ethiopian sheep, goats, and cattle sera. BMC Microbiol. 2023; 23: 216.

- Desquesnes M, Gonzatti M, Sazmand A, Thévenon S, Bossard G, Boulangé A, et al. A review on the diagnosis of animal trypanosomoses. Parasit Vectors. 2022; 15: 64.

- Poester FP, Nielsen K, Samartino LE, Yu WL. Diagnosis of brucellosis.Open Vet Sci J. 2010; 4: 46-60.

- Xavier MN, Paixão TA, Poester FP, Lage AP, Santos RL. Pathological, immunohistochemical and bacteriological study of tissues and milk of cows and fetuses experimentally infected with Brucella abortus. J Comp Pathol. 2009; 140: 149-157.

- Colmenero JD, Morata P, Ruiz-Mesa JD, Bautista D, Bermúdez P, Bravo MJ, Queipo-Ortuño MI. Multiplex real-time polymerase chainreaction: a practical approach for rapid diagnosis of tuberculous and brucellar vertebral osteomyelitis. Spine. 2010; 35: E1392-E1396.

- Queipo-Ortuño MI, De Dios Colmenero J, Macias M, Bravo MJ, MorataP. Preparation of bacterial DNA template by boiling and effect of immunoglobulin G as an inhibitor in real-time PCR for serum samples from patients with brucellosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008; 15: 293- 296.

- Zhang N, Huang D, Wu W, Liu J, Liang F, Zhou B, et al. Animal brucellosis control or eradication programs worldwide: a systematic review of experiences and lessons learned. Prev Vet Med. 2018; 160: 105-115.

- Zamri-Saad M, Kamarudin MI. Control of animal brucellosis: TheMalaysian experience. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2016; 9: 1136-1140.

- Pal M, Gizaw F, Fekadu G, Alemayehu G, Kandi V. Public health and economic importance of bovine Brucellosis: an overview. Am J Epidemiol. 2017; 5: 27-34.

- Tariku S. The impact of brucellosis on productivity in improved dairy herd of Chaffa State Farm, Ethiopia. Berlin, Freiuniversity, Fachburg Veterinary medicine (Doctoral dissertation, Msc Thesis).

- Godfroid J, Garin-Bastuji B, Saegerman C, Blasco JM. Brucellosis in terrestrial wildlife. Rev Sci Tech. Office International des Epizooties. 2013; 32: 27-42.

- Al Dahouk S, Sprague LD, Neubauer H. New developments in the diagnostic procedures for zoonotic brucellosis in humans. Rev Sci Tech. 2013; 32: 177-188.

- Poester FP, Samartino LE, Santos RL. Pathogenesis and pathobiology of brucellosis in livestock. Rev sci tech. 2013; 32: 105-115.

- Cutler SJ, Whatmore AM, Commander NJ. Brucellosis–new aspects ofan old disease. J Appl Microbiol. 2005; 98: 1270-1281.

- Jergefa T, Kelay B, Bekana M, Teshale S, Gustafson H, Kindahl H. Epidemiological study of bovine brucellosis in three agro-ecological areas of central Oromiya, Ethiopia. Rev sci tech. 2009; 28: 933-943.

- Mussie H, Tesfu K, Yilkal A. Seroprevalence study of bovine brucellosis in Bahir dar milk shed, northwestern amhara region. Ethiop Vet J. 2007; 11: 42-49.

- Getahun TK, Mamo G, Urge B. Seroprevalence of bovine brucellosis and its public health significance in central high land of Ethiopia. 2021.

- Edao BM. Brucellosis in Ethiopia: epidemiology and public healthsignificance (Doctoral dissertation). 2021.

- Lado D, Maina N, Lado M, Abade A, Amwayi S, Omolo J, et al. Brucellosis in Terekeka counTy, cenTral equaToria sTaTe, souThern sudan. East Afr Med J. 2012; 89: 28-33.

- Lita EP, Erume J, Nasinyama GW, Ochi EB. A Review on Epidemiology and Public Health Importance of Brucellosis with Special Reference to Sudd Wetland Region South Sudan. 2016; 4: 7-13.

- Kebede T, Ejeta G, Ameni G. Seroprevalence of bovine brucellosis in smallholder farms in central Ethiopia (Wuchale-Jida district). Rev Méd Vét. 2008; 159: 3-9.

- G?owacka P, ?akowska D, Naylor K, Niemcewicz M, Bielawska-DrozdA. Brucella–virulence factors, pathogenesis and treatment. Pol J Microbiol. 2018; 67: 151-161.

- Al-Tawfiq JA. Therapeutic options for human brucellosis. Expert revanti-infect ther. 2008; 6: 109-120.

- Munir R, Afzal M, Hussain M, Naqvi SM, Khanum A. Outer membrane proteins of Brucella abortus vaccinal and field strains and their immune response in buffaloes. Pak Vet J. 2010; 30: 110-114.

- Ibrahim N, Belihu K, Lobago F, Bekana M. Sero-prevalence of bovine brucellosis and its risk factors in Jimma zone of Oromia Region, South-western Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2010; 42: 35-40.

- MUSA AM, ROBA HM. COLLEGE OF VETERINARY MEDICINE. 2021.

- Maudlin I, Eisler MC, Welburn SC. Neglected and endemic zoonoses.Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2009; 364: 2777-2787.

- Abbas BA, Aldeewan AB. Occurrence and epidemiology of Brucella spp. in raw milk samples at Basrah province, Iraq. Bulg J Vet Med. 2009; 12: 136-142.

- Yohannes M, Degefu H, Tolosa T, Belihu K, Cutler RR, Cutler S. Brucellosis in Ethiopia. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2013; 7: 1150-1157.

- Tsegay A, Tuli G, Kassa T, Kebede N. Seroprevalence and risk factors of Brucellosis in small ruminants slaughtered at Debre Ziet and Modjo export abattoirs, Ethiopia. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2015; 9: 373-380.

- Edao BM, Ameni G, Assefa Z, Berg S, Whatmore AM, Wood JL. Brucellosis in ruminants and pastoralists in Borena, Southern Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020; 14: e0008461.

- Muhidin M, Degafu H, Abdurahaman M. Seroprevalence of brucellosis in small ruminants, its risk factors, knowledge, attitude and practice of owners in Berbere district of Bale Zone southeast Ethiopia. Ethiop J Appl Sci Technol. 2021; 12: 10-23.

- Teshome D, Sori T, Banti T, Kinfe G, Wieland B, Alemayehu G. Prevalence and risk factors of Brucella spp. in goats in Borana pastoral area, Southern Oromia, Ethiopia. Small Ruminant Res. 2022; 206: 106594.

- Tschopp R, Gebregiorgis A, Tassachew Y, Andualem H, Osman M, Waqjira MW, et al. Integrated human-animal sero-surveillance of Brucellosis in the pastoral Afar and Somali regions of Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021; 15: e0009593.

- Adem A, Hiko A, Waktole H, Abunna F, Ameni G, Mamo G. Small Ruminant Brucella Sero-prevalence and potential risk factor at Dallo- Manna and HarannaBulluk Districts of Bale Zone, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. Ethiop Vet J. 2021; 25: 77-95.

- Dubie T, Kasa T, Kinfe G, Bulbula A, Asgedom H. Seroprevalence and Associated Factors of Small Ruminant Brucellosis in the Dubti District of the Afar Region, Ethiopia. Vet Med Int. 2025; 2025: 7469192.

- Getachew S, Kumsa B, Getachew Y, Kinfu G, Gumi B, Rufaele T, et al. Seroprevalence of Brucella infection in cattle and small ruminants in South Omo zone, southern Ethiopia. Ethiop Vet J. 2023; 27: 125-144.

- Dima FG, Shahali Y, Dadar M. Prevalence and associated risk factors of brucellosis in sheep and goat. 2021.

- Zewdie W. Study on sero-prevalence of small ruminant and human brucellosis in Yabello and Dire districts of Borena zone Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. Am J Anim Vet Sci. 2020; 15: 26-31.

- Atlaw T, Girma Y. Sero-Prevalence of Caprine Brucellosis in Babile Woreda, Eastern Hararghe, Ethiopia. Dairy Vet Sci J. 2019; 10: 1-5.

- Demena GK. Small ruminant brucellosis and awareness of pastoralist community about zoonotic importance of the disease in yabello districts of Borena zone Oromiya regional state, Southeren Ethiopia. Int J Infect Dis. 2019; 79:72.

- Chaka H, Aboset G, Garoma A, Gumi B, Thys E. Cross-sectional survey of brucellosis and associated risk factors in the livestock–wildlife interface area of Nechisar National Park, Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2018; 50: 1041-1049.

- Teshome A, Geremew H, Lijalem N. Asero-prevalence of small ruminant brucellosis in selected settlements of Dire Dawa Administrative Council Area, Eastern Ethiopia. ARC J Immunol Vaccin. 2018; 3: 7-14.

- Addis SA, Desalegn AY. Comparative seroepidemiological study of brucellosis in sheep under smallholder farming and governmental breeding ranches of Central and North East Ethiopia. J Vet Med. 2018; 2018: 7239156.

- Kelkay MZ, Gugsa G, Hagos Y, Taddelle H. Sero-prevalence and associated risk factors for Brucella sero-positivity among small ruminants in Tselemti districts, Northern Ethiopia. J Vet Med Anim Health. 2017; 9: 320-326.

- Dulo F. Seroprevalence of Caprine Brucellosis and Its Associated Risk Factor in Mirab Abaya district, South Eastern Ethiopia. J Natu Sci Res. 2017; 7.

- Erkyihun GA, Gari FR, Kassa GM. Bovine brucellosis and its publichealth significance in Ethiopia. Zoonoses. 2022; 2: 985.

- Díez JG, Coelho AC. An evaluation of cattle farmers’ knowledge of bovine brucellosis in northeast Portugal. J Infect Public Health. 2013; 6: 363-369.