Effectiveness of Simulation Training for Vaginal Hysterectomy (Using a Commercially Available High-Fidelity Model)

- 1. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Inspira Health Network at 2950 College Drive Suite 2A, United States of America.

- 2. Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology at NYU Grossman Long Island School of Medicine, United States of America.

Abstract

Importance: The hands-on simulations provide a safe environment for the learners to practice surgical steps and to increase confidence.

Objectives: To investigate the effectiveness of an educational intervention to teach major pelvic landmarks and basic steps of Vaginal Hysterectomy (VH) to the Obstetrics & Gynecology (OBGYN) residents, using a commercially available high-fidelity model.

Study Design: This is educational research: after didactic lecture, residents were paired and performed VH simulation on a commercially available VH model, guided by a board-certified urogynecologist, with step-by-step instructions. Demographics and assessments on confidence level, knowledge pretest/posttest, and satisfaction survey were collected. Demographics/survey questions were expressed using a descriptive analysis. The test scores were compared within groups using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Results: 11 residents (1PGY1, 2PGY2s, 4PGY3s, 4PGY4s) participated. The median age of residents was 31-year-old [IQR 29,32]. The median number of VH performed was 0.0[0.0, 5.5] and the number of VH observed was 1.0[1.0, 2.0], although the total number of completed GYN rotations was 11[6.5, 11.5]. The median score from the 25 multiple- choice knowledge questions on the pre-test was 72% [IQR 62, 78], while that of post-test was 80% [IQR 66, 80], (p=.030). Self-assessed confidence level scores improved from 3 to 4(1-lowest, 5-highest) in all questions asked. 100% of residents responded with 4 and 5(1-lowest, 5-highest) to the satisfaction statements.

Conclusions: A commercially available VH model increased residents’ confidence and knowledge scores in performing VH. This VH model can serve as an alternative method to teach the basic steps and surgical skills of VH to the OBGYN residents.

KEYWORDS

- Vaginal hysterectomy

- Surgical Education

- Surgical Simulation

CITATION

Chong W (2025) Effectiveness of Simulation Training for Vaginal Hysterectomy (Using a Commercially Available High-Fidelity Model). Med J Obstet Gynecol 13(1): 1194.

Simply Stated

The hands-on simulations provide a safe environment for the learners to practice surgical steps and to increase confidence. A commercially available vaginal hysterectomy model would provide an excellent way of reviewing the major pelvic landmarks and basic steps of vaginal hysterectomy for the OBGYN residents. In addition, the hands-on simulation also increased the residents’ confidence level.

Why This Matters? Vaginal hysterectomy is a preferred surgical route to address benign gynecologic indications for multiple reported benefits. However, there has been a decreasing trend in vaginal hysterectomy for the past decades, while the number of (robotic assisted) laparoscopic hysterectomy has been increasing. This trend can be translated to less experiences for OBGYN residents to perform vaginal hysterectomy. The commercially available realistic pelvic model can serve as an alternative method to teach pelvic anatomy and the basic steps of vaginal hysterectomy to the OBGYN residents.

INTRODUCTION

Vaginal hysterectomy (VH) is the preferred route of surgery for benign indications per American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) [1].There have been numerous reported benefits to VH when compared to other routes of surgery, including decreased length of hospital stay, decreased operative time, less postoperative pain and quicker recovery [2]. VH also has lower rates of intraoperative and postoperative complications when compared to robotic, laparoscopic and open hysterectomies [3]. In addition, VH has the lowest overall cost and is the only minimally invasive route that generates net income [4].

Despite these benefits, there has been a decreasing trend in VH performed although the rate of laparoscopic with/ out robotic assistance minimally invasive hysterectomy rates has significantly increased [5]. The overall number of hysterectomies performed/participated by OBGYN residents has been decreasing with a higher rate of decline for abdominal and vaginal routes [6]. The decline in VH case log numbers translates to less experience for OBGYN residents. According to an online survey, only 38.1% of program directors and 27.8% of residents reported graduating residents as being “completely prepared” to perform a VH [7].

Simulations certainly have a role in training residents, providing a safe environment for learning and practicing, in addition to increasing confidence. Currently, there are several cost-effective VH simulators available at the ACOG website [8-10]. However, they are time consuming to build each model with relatively complex steps involved. There are studies to suggest that low-cost models can also offer improved resident confidence. In a pilot study, 14 residents were able to successfully perform the steps of a VH and confidence was increased using a low-cost model. However, the construction and reloading were time consuming. Another low-cost model, developed by Anand (2016), teaches the basic steps of VH utilizes paper/plastic bag construction of the pelvic structures however it does not offer to practice basic surgical skills with clamp-cut- suture ligating surgical techniques [11-13].

Although the commercially available simulation pelvic model (The Miya Model ™ (Miyazaki Enterprises, Winston- Salem, NC, USA) costs $6,500, and its disposable and non-reusable structures cost $440, with a newer, more simplified version of uterus and vagina costing less than $200 [14], it mimics the most realistic pelvic structures and offers realistic surgical practice. In addition, the model can be utilized for multiple other uro/gynecologic procedures like cystoscopy, hysteroscopy, midurethral sling placement and vaginal apical suspensions (i.e. uterosacral ligament suspension and sacrospinous ligament fixation).

The objective of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of an educational intervention by measuring improvement of residents’ knowledge and confidence level to teach the basic steps of VH, using the commercially available Miya Model.

STUDY DESIGN

The educational research was conducted during resident teaching sessions at Inspira Medical Center in Vineland, New Jersey (NJ). Inspira Health Institutional Review Board approval (IRB00002854) was obtained. The matched pairs were utilized in pre/posttest methodology to assess the efficacy and perceptions of VH simulation using a commercially available Miya pelvic model [14].

The residents were invited to participate in the project when attending the routinely scheduled didactic sessions on March 22 and April 5, 2024. The voluntary consent was obtained before the educational intervention. OBGYN residents at Inspira Medical Center in Vineland, NJ were included. Non-Inspira OBGYN residents, non-OBGYN residents, and vulnerable populations, including medical students, were excluded from the data analysis.

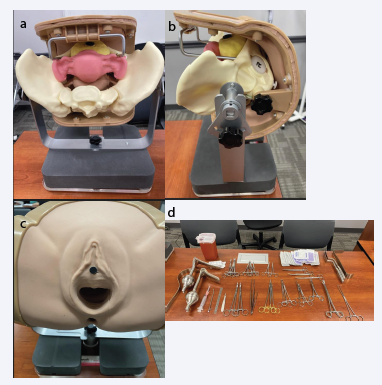

The study was conducted in a single 3.5-hour simulation session with the following sequences: (1) 30 minutes: Pre-Intervention Demographic Assessment (Appendix 1 –Demographics), Confidence Level Self- Assessment before Simulation (Appendix 2), and, the Pre- Test Knowledge Assessment (Appendix 3); (2) 60 minutes: didactic session, using the Miya Model for Simulation (Supplement 1 – Lecture Slides in PowerPoint); (3) 90 minutes: individually practicing/performing the basic steps of VH on the Miya Model under direct supervision of a board-certified Urogynecologist (Figure 1 for the model and surgical instrument set up); and, (4) 30 minutes: the Post-Test Knowledge Assessment (Appendix 3) and Post-Intervention Confidence/Satisfaction Assessments (Appendix 4 – Confidence Level Self-Assessment before Simulation & Appendix 5 – Satisfaction Survey).

Figure 1: The Miya Pelvic Model from different views and Surgical Tool Set up

The Miya Pelvic Model from different views and Surgical Tool Set up: (a) Internal View of the Model, (b) Lateral View of the Model, (c) Surgical View of the Model, and (d) Surgical Tool Set Up.

The questionnaires were collected without personal identifiers. Each subject was self-assigned with coded study identification, using a 4 digits code (“last digit of your cell phone number”, “last digit of the year you graduated from high school”, “your number of sisters (1 digit)”, “last day of your birthdate day (ex. for 16th –enter 6)”.

Outcomes were measured with the written knowledge test before and after the simulation and a self-graded survey for confidence and satisfaction. The pre-post knowledge assessments on pelvic anatomy and the basic steps of VH were prepared by the author (total 25 questions on the 100-point system, see Appendices 3).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using commercially available software: R v.4.0.3 (Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, URL: http://www.R-project.org/). The demographic variables and subjectively reported satisfaction survey on the model were described using descriptive analysis, since there was no control group to compare. The primary outcome was calculated using a bivariate analysis evaluating the written test scores before and after the VH simulation. The confidence score in performing VH after the intervention was also compared within the groups as the secondary outcome. Pre- and post-test scores on the written test were compared within groups using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. All reported p values were 2-sided, and p <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of a total of 14 residents (4 each for PGY3&4 levels and 3 each for PGY1&2 levels) in the OBGYN residency program, 11 participated in the simulation (PGY1, n=1; PGY2, n=2; PGY3, n=4; PGY4 n=4). The median age of residents was 31-year-old [IQR 29,32]. The median number of VH performed was 0.0 [0.0, 5.5] and the number of VH observed was 1.0 [1.0, 2.0], although the total number of completed GYN rotations was 11 [6.5, 11.5] (Table 1).

Table 1: Demographics

|

Variable |

Response (median [IQR]) |

|

|

Total |

|

11 |

|

Age (years) |

31 [29, 32] |

|

|

Training Year (PGY) (%) |

N |

(%) |

|

1 |

1 |

9.1 |

|

2 |

2 |

18.2 |

|

3 |

4 |

36.4 |

|

4 |

4 |

36.4 |

|

Number of VH performed |

0 [0, 5.5] |

|

|

Number of VH participated |

0 [0, 4.5] |

|

|

Number of VH observed |

1 [1, 2] |

|

|

Number of Completed GYN rotations |

11 [6.5, 11.5] |

|

PGY: post-graduate year, VH: vaginal hysterectomy, GYN: gynecology

The median score from the knowledge questions on the pre-test was 72% [IQR 62, 78], while that of post- test was 80% [IQR 66, 80], (p=.030) (Table 2).

Table 2: Knowledge test scores before and after simulation

|

Test Scores |

Before Simulation (n=11) |

After Simulation (n=11) |

p-value |

|

Raw test score: 25 total (median [IQR]) |

18 [15.5, 19.5] |

20 [16.5, 20] |

0.30 |

|

100 scale test score (median [IQR]) |

72 [62,78] |

80 [66, 80] |

0.30 |

IQR: Interquartile range

Self- assessed confidence level scores improved from 3 to 4 (1-lowest, 5-highest) in three questions asked: Question 1: “knowledge of vaginal pelvic anatomy”, Questions 2: “Identification of the pelvic landmarks during VH”, and Questions 3: “Understanding the basic steps of how to perform VH” (Table 3)

Table 3: Self-assessment of confidence level before and after simulation

|

Confidence Level Self-Assessment |

Response |

Before Simulation (n=11) |

After Simulation (n=11) |

p-value |

|

Q1 |

median [IQR] |

3 [3, 4] |

4 [3.5, 4] |

0.17 |

|

2 (%) |

2 (18.2) |

1 (9.1) |

0.51 |

|

|

3 (%) |

4 (36.4) |

2 (18.2) |

|

|

|

4 (%) |

5 (45.5) |

7 (63.6) |

|

|

|

5 (%) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (9.1) |

|

|

|

Q2 |

median [IQR] |

3 [2.5, 3.5] |

4 [3.5, 4] |

0.18 |

|

1 (%) |

1 (9.1) |

0 (0.0) |

0.19 |

|

|

2 (%) |

2 (18.2) |

0 (0.0) |

|

|

|

3 (%) |

5 (45.5) |

3 (27.3) |

|

|

|

4 (%) |

3 (27.3) |

7 (63.6) |

|

|

|

5 (%) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (9.1) |

|

|

|

Q3 |

median [IQR] |

3 [3, 4] |

4 [4, 4] |

0.02 |

|

2 |

1 (9.1) |

0 (0.0) |

0.07 |

|

|

3 |

6 (54.5) |

1 (9.1) |

|

|

|

4 |

3 (27.3) |

8 (72.7) |

|

|

|

5 |

1 (9.1) |

2 (18.2) |

|

|

|

Q1: Knowledge of vaginal pelvic anatomy? |

|

|||

|

Q2: Identification of the pelvic landmarks during VH? |

||||

|

Q3: Understanding the basic steps of how to perform VH? |

||||

VH: vaginal hysterectomy, IQR: Interquartile range

On satisfaction survey at the end of the simulation, 100% of residents responded with 4 or 5 (1-lowest, 5-highest) to the statements for “Usefulness of the lecture”, “realism of Miya model for VH simulation”, and “Usefulness of the simulation exercise” (Table 4).

Table 4: Satisfaction scores after simulation

|

Satisfaction Question |

Response: Median [IQR] |

|

Usefulness of the lecture |

5 [4, 5] |

|

Realism of the TVH Miya model for simulation VH |

4 [4, 4.5] |

|

Usefulness of the simulation exercise |

5 [4, 5] |

VH: vaginal hysterectomy

DISCUSSION

In this study, the commercially available realistic pelvic model was utilized to assess the OBGYN residents’ knowledge scores and confidence/satisfaction levels in performing VH, before and after the simulation session.

It is well-known that simulation training enhances the learner’s knowledge on anatomy and basic steps of complex procedures without compromising patient safety. VH is one of the complex procedures that requires knowledge on complex anatomic relationships of vital structures within the relatively restricted space of the bony pelvis: this may limit the ability of teaching VH to the learners [14].

There are several VH simulation models available, including Low Fidelity Trainer [8,9,11-13], and Reusable Pelvic Simulator [15,16]. Almost all the currently available Low Fidelity and Reusable simulators require construction and reloading the parts on the bony pelvis, which take time to prepare the reloading parts of the simulation, although they are more economically affordable, compared to the commercially available realistic pelvic model, like Miya model. The common criticism of on the Low Fidelity simulation models is the lack of fidelity, i.e., “synthetic models do not feel lifelike and therefore does not simulate live surgery when used for surgical practice” [14,17,18].

In contrast, the Miya model does not require complex construction of the reloading the parts, but it requires to replace the used portion of the pre-made structures.

According to Miyazki. et al, (2019) [14], the model is only 6.5 pounds and easily portable. The model “exhibits realistic visceral and vascular anatomy as well as bony landmarks and tissue planes which mimics the tissue tension a surgeon would experience operating on biologic tissue”. Besides the pelvic model, there are eight replaceable parts: vulva, vagina, uterus tubes and ovaries, bladder, obturator membrane, perineum and sacrospinous ligament. Each piece is designed to mimic real tissue from feel, cutting and suturing. In addition, the model can be utilized for other types of surgical simulation including cystoscopy, hysteroscopy, midurethral sling placement and vaginal vault suspension.

Practicing VH on the Miya Model with step-by-step instructions improved OBGYN residents’ knowledge scores and self-assessed confidence level on pelvic anatomy and basic steps of performing VH. In addition, all participants were satisfied with the educational activity.

Strengths of this study included the use of high-fidelity pelvic model like the Miya Model to teach the basic steps of VH to the OBGYN resident. Having a valid and reliable simulation model for assessing VH skills is important, and it is equally important to have a simulation model for learning VH skills and anatomy relationships in the pelvis. The Miya model satisfies both. Limitations of this study included the small number of participants and lack of validation of the model for assessing the residents’ VH skill improvement in the real operative room setting.

In conclusion, a commercially available high-fidelity VH model increased residents’ confidence and knowledge scores in performing VH. This VH model can serve as an alternative method to teach the basic steps and surgical skills of VH to the OBGYN residents.

REFERENCES

- Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Committee Opinion 701. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 129: 155-159.

- Aarts J, Nieboer T, Johnson N, Tavender E, Garry R, William J Mol B, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015: CD 003677.

- Rahimi S, Jeppson PC, Gattoc L, Westermann L, Cichowski S, Raker C, et al. Comparison of perioperative complications by route of hysterectomy performed for benign conditions. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2016; 22: 364-368.

- Abdelmonem A. Observational Comparison of Abdominal, Vaginal and Laparoscopic Hysterectomy as Performed at a University Teaching Hospital. J Reprod Med. 2006; 12: 945-954.

- Kandahari N, Tucker LY, Ojo A, Zaritsky E. Factors Associated with Variation in Vaginal Hysterectomy Rates in an Integrated Health Care System [18B]. Obstet Gynecol. 2020; 135: 23S

- Gressel G, Potts JR, Cha S, Valea FA, Banks E. Hysterectomy Route and Numbers Reported by Graduating Residents in Obstetrics and Gynecology Training Programs. Obstet Gynecol. 2020; 135: 268-273

- Burkett D, Horwitz J, Kennedy V, Murphy D, Graziano S, Kenton K. Assessing current trends in resident hysterectomy training. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2011; 17: 210-214.

- Vaginal hysterectomy task trainer: gynecologic tasks and skills series. ACOG. 2024.

- Braun K, Henley B, Ray C, Stager R. Teaching Vaginal Hysterectomy: Low Fidelity Trainer Provides Effective Simulation at Low Cost. Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 130: 44S

- Guntupalli SR, Doo DW, Guy M, Sheeder J, Omurtag K, Kondapalli L, et al. Preparedness of obstetrics and gynecology residents for fellowship training. Obstet Gynecol 2015; 126: 559-568.

- Anand M. The no-excuses vaginal hysterectomy model. Poster presentation at the American Urogynecologic Society Annual Scientific Meeting; September 27-October 1, 2016; Denver, CO. ePoster 100. Female Pelvic Medicine Reconstructive Surg. 2016; 22: S71-S151.

- Anand M, Duffy CP, Vragovic O, Abbassi W, Bell SL. Surgical Anatomy of Vaginal Hysterectomy-Impact of a Resident-Constructed Simulation Model. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018; 24: 176-182.

- Chong W. Reeves M, Bui A. Effectiveness of Simulation Training for Vaginal Hysterectomy, Using a Low-Cost Model. Biomed J Sci Tech Res. 2022; 46.

- Miyazaki D, Matthews CA, Kia MV, El Haraki AS, Miyazaki N, Grace Chen CC. Validation of an educational simulation model for vaginal hysterectomy training: a pilot study. Int Urogynecol J. 2019; 30: 1329-1336.

- Barrier BF, Thompson AB, McCullough MW, Occhino JA. A novel and inexpensive vaginal hysterectomy simulator. Simul Healthc. 2012; 7: 374-379.

- Malacarne DR, Escobar EM, Lam CJ, Ferrante KL, Szyld D, Lerner VT. Teaching Vaginal Hysterectomy via Simulation: Creation and Validation of the Objective Skills Assessment Tool for Simulated Vaginal Hysterectomy on a Task Trainer and Performance Among Different Levels of Trainees. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019; 25: 298-304

- Aggarwal R, Darzi A. Technical-skills training in the 21st century. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355: 2695-2696.

- Nwamaka MA, Onwugbenu M. Vaginal Hysterectomy Simulation: Adjunct Training. Obstetr Gynecol. 2015; 126: 53S-54S.