PreTerm PreLabor - A Clinical Entity Retrieved from Ancient OB Scrolls

- 1. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University City, USA

Keywords

• Preterm labor; Obstetric patients; Clinical data

Citation

Zalar RW (2025) PreTerm PreLabor - A Clinical Entity Retrieved from Ancient OB Scrolls. Med J Obstet Gynecol 13(1): 1195

Abastract

This paper dealt with the prevention of “spontaneous” preterm labor. In the early 1990’s several forces had merged which led to my clinical practice seeing a very large volume of obstetric patients. These numbers became a de facto cohort and with the increased availability of computers and improved software the collection of clinical data was becoming easier and more precise.

PREFACE

It was an ordinary twenty-first century day. I was just scanning my emails and noticed one from academia. edu. I was aware of Academia at the time but had had no previous direct connection. In their email they wanted to inform me that there were some requests about one of my obstetric research papers from the 1990’s which had usually only been generally available as an abstract. These individuals were seeking the full paper and Academia asked me if I could help.

I was a bit surprised for that work to get attention now since it had been more than 25 years (!) since publication. As it turns out I did have reprints (!) of the paper in a box in a closet at home. (Since I had been a clinical, not academic, obstetrician there were only a few papers, making the search easy.) I scanned the full paper - (Zalar RW Jr. Early cervical length, preterm prelabor and gestational age at delivery.

Is there a relationship? J Reprod Med. 1998 Dec;43(12):1027-33. PMID: 9883406) - and sent it to Academia and it now appears on a site there under my name with my other papers.

This paper dealt with the prevention of “spontaneous” preterm labor. In the early 1990’s several forces had merged which led to my clinical practice seeing a very large volume of obstetric patients. These numbers became a de facto cohort and with the increased availability of computers and improved software the collection of clinical data was becoming easier and more precise. A clinical entity soon became apparent to me and it changed my prenatal care: the first, sometimes lingering, step on the final common pathway to “spontaneous” preterm labor and birth is something I called Preterm Prelabor (PTPL). It is characterized by preterm shortening of cervical length (corresponding to symptoms of cervical effacement) with or without increased uterine activity. Acting on this precursor can be a simple example of early intervention similar to the broken windows theory in law enforcement: notice and respond to the little things to stop the big things. As a back of the envelope meta-analysis of the above paper combined with another paper1 of mine on the same topic, out of 747 singleton prenatal patients there were 0 spontaneous preterm births <1500gm (first paper) or <30 weeks gestation (second paper).

This would seem to be a good start on the resolution of the problem. Unusual circumstances led to my early retirement from obstetric practice and although I was pleased with these two papers I had not paid much further attention to them until I received the email from Academia. Progress in the prevention of “spontaneous” preterm labor seems much less than I would have expected 30 years ago and the clinical entity of Preterm Prelabor unfortunately has not yet been accepted.

At this point in time I would like to retrieve the ancient OB scrolls that contain these ideas, add to them some secondary discussion, and leave them as a signpost or marker to help reach future success in the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth.

PRETERM PRELABOR - SUPPLEMENTAL NOTES #1

Definitions - What is preterm prelabor? The most common clinical precursor of spontaneous preterm labor is Preterm Prelabor (PTPL): it is characterized by preterm shortening of cervical length (corresponding to symptoms of cervical effacement) with or without increased uterine activity. What is preterm increased uterine activity? Starting at 20 wks gestation, as perceived by the pregnant woman, Braxton Hicks (BH) contractions 10 or more per day and at least 30 seconds duration. What is normal cervical length after 20 weeks? >30 mm [1], only if no symptoms of PTPL are present. What is an acceptable cervical length at end of the first trimester (in particular at ~11 weeks gestational age)? >40 mm (10th percentile) and ideally >45 mm.

INTRODUCTION

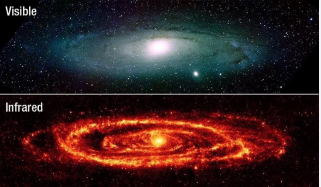

When there is an onset of disease or abnormality during the course of a life time or pregnancy time one might expect that are changes prior to clinical onset that can be identified and then managed to the benefit of the patient. Examples during life time would include Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. In pregnancy time the first example of such an abnormality is Eclampsia and its precursor Pre-eclamsia. Another example is “Spontaneous” Preterm Labor and Birth.Blurred light from the universe can be seen from earth and from earlier orbiting telescopes. The James Webb orbiting telescope is specialized to see with greater precision infrared light that the earth’s atmosphere would otherwise block out. In this galaxy light can be seen to spiral toward the core. Infrared light is the analogy for visualizing Preterm Prelabor (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The James Webb orbiting telescope specialized to see with greater precision infrared light that the earth’s atmosphere would otherwise block out.

The most common clinical precursor of spontaneous preterm labor and birth is Preterm Prelabor (PTPL): it is characterized by shortening of cervical length with or without increased uterine activity. Cervical length can easily be measured by TransVaginal Ultrasound (TVUS). Increased uterine activity in this setting is not preterm labor. In fact, if the obstetrician identifies the preterm labor process when the pregnant woman shows up in Labor and Delivery preterm and says “I think I’m going into labor,” the opportunity has been missed, the die has been cast, and there is little to be done to extend the pregnancy. While increased uterine activity in PTPL is simply more frequent Braxton Hicks (BH) contractions, they should not be ignored, and while it is true that they are not labor and usually are painless, it must also be remembered the main job of uterine muscle during pregnancy is relaxation to accommodate huge growth. After all, the uterus increases from roughly the size of a small flat pear before pregnancy to the size of a large watermelon at nine months.

Similarly, the fetus grows tremendously in half that time from 300 grams at 20 weeks to about 3400 grams at 40 weeks. Successful uterine quiescence is essential for the pregnancy to reach full term. BH contractions are significant if they are perceived by the pregnant woman to be >10 per day and >30 seconds duration and may mark the the first step on the final common pathway leading to “spontaneous” preterm labor and birth. Braxton-Hicks contractions and the education of the pregnant woman As Mark Twain or Ernest Hemingway might have said about how “spontaneous” preterm labor starts: first gradually (PTPL), then suddenly (PTL).

Everyone wants credit for this one. The prenatal visit at ~22 weeks gestation is a prime time to educate the pregnant woman as to what a BH contraction feels like. Often at this time there is not very much for the obstetrician (OB) to say about her pregnancy. She is obviously pregnant. Everyone wants to ask her about it: they have no fear of being wrong. Whatever early nausea and/or vomiting she has had is now mostly gone. She is eating better. She is gaining some weight. She is sleeping better. She is feeling better. She is feeling fetal movement. The baby is not that big yet. In fact, some women have said that they feel so good at 22 wk they otherwise barely feel pregnant, except, of course, they are.

This prenatal visit can reduce to merely a social visit, but there is work to be done so the patient can know what BH contractions feel like and how many are too many. Every patient should get this “talk” as a part of routine prenatal care. The shape of the pregnant uterus is now well defined. By using a hands-on technique - literally, with both hands - during abdominal examination of the pregnant woman the OB can gently squeeze the uterus from both sides along the longitudinal axis and then relax the squeeze, imitating a BH contraction.

Frequently the patient may even say “so that’s what that is!” The OB should then say that the uterus, like any muscle, will get hard all over when it contracts so that if she tries to make a dent with her fingers it won’t dent anyplace. There is good muscle definition during a BH contraction so that she can feel the edges more clearly and the uterus may push forward or stand up a bit in the abdomen, depending on maternal position. Lastly, the OB should say when she is most likely to notice BH contractions: in the late afternoon or evening, especially if she feels very tired. The OB should then describe what BH contractions are not. If she feels tightening in just one part of the uterus, probably that’s just part of the baby pressing to the outside. She may have experienced this kind of fetal movement already.

Sometimes the baby will be very active and the uterus might feel hard at the same time. That hardness is probably just from the movements. Prenatal patient education is essential for the recognition of BH contractions. Many first-time pregnant women may expect to watch for pain, which would be misleading. It is curious that the understanding of uterine activity is so easy for the physician and so difficult for the patient without education. And it is just as curious that the symptoms of cervical effacement are so easy for the patient and so difficult for the physician. If BH contractions can be perceived by the pregnant woman >10 times per day and >30 seconds duration, measurement of cervical length by TVUS is warranted to determine if any PTPL care is indicated. While it is clear that that the she will not notice all BH contractions, it is also clear that her threshold perception of contractions matters and has proved useful in these two studies.

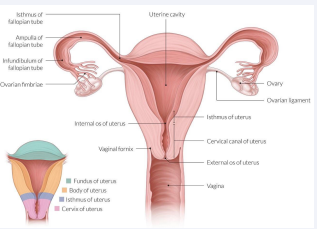

These details are discussed in my first paper [1], on preterm prelabor. A second paper [2], looked to see if cervical length measurement at 11 wk gestation has predictive value for PTPL (it does). Early Cervical Length: at ~11 weeks gestation A short cervix at ~11 wk identified by TVUS indicates that the usual establishment of the pregnancy may not be occurring. In the early first trimester the fertilized egg has developed to the blastocyst stage when it implants in the uterus. It continues to take shape during the embryonic stage and reaches the fetal stage by the end of the first trimester. The parts of the uterus of special concern at this time are the body, the isthmus (which later in pregnancy expands to become the lower segment), and the cervix.

The isthmus during this time has a choice (to anthropomorphize a bit): it can join the body or it can join the cervix. The right answer is cervix, which may need help during pregnancy to become functionally robust to carry and hold the fetus in utero until full term. The Cervix + Isthmus together do this work. This enhanced cervix at 11 wk should be longer (>40 mm, and ideally >45 mm) than a non-pregnant cervix (~25 mm). If this change is not happening, close antepartum follow-up is indicated (Figure 2).

Figure 2: “isthmus of uterus” in each drawing (Copyright 2023 AMBOS).

The main precursor of spontaneous preterm labor is PTPL. The main precursor of PTPL is a short functional cervix at 11wk, which then requires repeat measurement by TVUS at18-19 wk and prompt cervical cerclage if there is shortening to 25 mm or less. In this study of early cervical length about 60% of early short cervices developed PTPL and about one half of the them required cerclage before 20 wk because of further shortening. On the other hand, functional cervical length actually normalized by that time in about 40% of cases allowing for routine prenatal care, which still included patient education about BH contractions. Again, most of the cases of early shortness at 11 wk are not so much a matter of early cervical shortening, but rather that the isthmus has not functionally joined the cervix to establish support for the pregnancy in the first place. Because the cervix is not becoming “pregnancy long” the weakness of its “pregnancy short-ness” may require cerclage or PTPL care. On the other hand, cervical length >45 mm identifies low risk for both PTPL and spontaneous preterm labor.

As William Osler might have said about PTPL: “Listen to the patient and (s)he will tell you the diagnosis.”

1. There is an array of descriptions that the pregnant woman may have for these perceptions, predominantly after 20 weeks gestation. Below is a list of them in order of frequency, higher to lower, as told to me by patients in my practice. If any of these symptoms are present, examination by TVUS is indicated to measure cervical length:Feeling like her period is about to start.

2. Feeling vaginal, rather than lower abdominal, pressure.

3. Feeling like it’s “opening up” or “spreading apart” vaginally. She may demonstrate these symptoms with her hands: if her hands reach low and her palms face each other, this is lower abdominal and probably not significant; if her palms press laterally against the upper inner thighs, this is vaginal/pelvic and is important.

4. Feeling like the baby is down too low and wants to fall out.

5. Feeling like she is in the last month of her pregnancy.

6. Feeling like she won’t last until her due date.

7. Feeling very swollen vaginally.

8. Feeling like the baby’s head is hitting the cervix.

9. Feeling like she wants to push the baby’s head back up.

10. Feeling like she needs to sit down or lie down to relieve any of the above symptoms. Also,

11. Feeling an increased, clear, mucous-like discharge.

12. Any vaginal spotting.

These descriptions are quite specific and require no prior education for the pregnant woman. She will recognize that something is “not right” and will readily want to report these symptoms to her physician. All live members of the office staff, including nurse practitioners and those screening patient phone calls, should be ready to facilitate this communication. Sometimes, however, there can be initial confusion about cervical effacement vs increased uterine activity. The key is for the physician then to see the patient, listen closely to her descriptions, recognize them, verify them, interpret them for her, and proceed with TVUS to see if PTPL care is indicated. The understanding of these symptoms may also help the patient to monitor herself clinically between visits until full term.

As noted, details of the management of PTPL are discussed at length, using a PTPL Matrix, in my first paper1 on this topic. Unfortunately, terbutaline, the tocolytic that I used in these old studies, has fallen out of favor apparently because of side effects. I would now suggest vaginal progesterone or nifedipine, as a possible candidate in a future revised strategy of PTPL care. Whatever is found must be available in more than one dosage level.

Basic Outpatient Strategy re PTPL

A. Universal TVUS @~11wk. (Can be referred for anatomic survey, but examination must include measurement of cervical length). Establish baseline measurement and accurate EDD. ID live fetus. ID twins. Or ID no embryo or fetus and impending spontaneous abortion. To see early fetal heartbeat and possible fetal movement is good for initial parental bonding with baby and may modify attitudes regarding abortion. Others also will hear these stories about what you can actually see. It’s Alive! It’s a real baby!

B. ID =45 at 11wk PTPL would be rare before 20wk. Verification in future cohorts would be useful.

C. Starting at 20wk with each prenatal visit, listen for patient’s worry about symptoms of preterm cervical effacement (PCE). Remember/see known descriptions. Be vague about low pressure so patient’s report is spontaneous and not an attempt to game the system. (If new description, add to list.). If positive symptoms, use TVUS to verify. (Also, use of TVUS inhibits gaming of system in the future.)

D. After 20wk/before24wk prenatal visit when the pregnant uterus is easily palpable on abdominal examination teach patient how to ID BHC’s and when to call. Pt to watch for BHC’s 10 or more per day, 30 seconds duration or longer. See slide: Catherine Spong 2008 re UC’s 1/hr. (Which would correspond to 10/day.) Note graph of UC’s starts at 28wk.

E. If PTPL is present, follow revised PTPL Matrix1: Stop work or work from home instead. Pt must have physical autonomy to help manage symptoms of PTPL. (As needed, sit down, lie down, or rest.) Need new tocolytic. Need a ladder of dosages. Appointments q2wk. (Routine q1wk is beyond tedious for pt and OB and not possible). If sx not improving (or worsening) before 2wk visit, pt should call office and promptly be seen for TVUS and recheck. Assess need for increased dose of tocolytic and modifcation of activity. Then generally, reschedule new 2wk visit. Only if very necessary, in one week.

G. Abdominal US to check fetal growth in early third trimester - check for too small (IUGR) or too large (macrosomia or polyhydramios). Either may promote PTPL.

H. Stop Rx between 36 and 37wk (closer to 37). Cut and remove cerclage. Stop tocolytic. Expect 50% will deliver by 38wk.

1. In this study the finding of short cervical length at 11 wk gestation was quite useful in identifying a group in that same pregnancy at high risk for more shortness before 20 wk, allowing for timely cerclage placement or very early diagnosis and management of PTPL. Again, in the future there will need to be a new tocolytic, perhaps vaginal progesterone or nifedipine, to replace terbutaline. Early measurement of cervical length at a short second visit at the best estimate of 11wk based on the new OB visit can screen for risk in all current pregnancies and not just those in women with a history of preterm birth. It also yields a more accurate EDD which can be useful in future investigations. Establishing a baseline early can allow trends to emerge if later TVUS becomes necessary. More studies will be needed to confirm the utility of early cervical length measurement found in this paper [2].

2. African-Americans in this study [2], appeared to have a greater proportion (~1.9x) of short cervical length at ~11 wk gestation and that may help to explain their well-known increased risk (2-3x) of PTB <32 wk. A population study with larger numbers would be important to validate this impression.

3. Concomitantly, a study to locate the site of implantation in each pregnancy would also be of interest. This location is marked by where the umbilical cord inserts and is quite easily seen with TVUS at 11wk. The placenta then grows radially, and frequently asymmetrically, from this spot usually toward more favorable areas of uterine blood supply the result of which can be seen during ordinary postpartum placental examination. The questions to be asked: is there a greater frequency of low implantation (especially in African-Americans) in cases of short early cervical length and might that explain an increased frequency of preterm birth, especially <30 weeks gestation?

4. And if that is the case, then why is there a greater chance of low implantation?

5. Comments on Parity: Multiparas (2-4) have longer early cervical length and less PTL risk than primiparas in this study. In labor primips generally have cervical effacement before dilatation; multips generally have dilatation before effacement. This basic knowledge would suggest that the body of the cervico-isthmic junction may somehow persist after first pregnancies to explain these differences in subsequent pregnancies.

6. More … Comments on Parity: In this study [2], with universal first trimester cervical measurement (at 11wk), cerclage performed because of progressive cervical shortening prior to 20 wk and appropriate PTPL management after 20 wk, no multips (222 of 373 total) delivered before 36 wk. Also, no nullips delivered before 30 wk. Form my 2 studies, 747 total births, 0< 30 wk, 0<1500 gm.