Pregnancy Experiences and Childhood Mortality in Rural Haiti

- 1. Department of Emergency Medicine, Harborview Medical Center, USA

Abstract

To better understand health risks and their social determinants for women and children in rural Haiti, we conducted a door-to-door survey of 5 villages. Our data revealed that pregnancy complications are common and that neonatal, infant, and under-five mortality in rural poor populations are approximately 200% higher in this region compared to national level estimates. These findings reveal important opportunities for further study and for intervention to decrease childhood deaths in this population.

Keywords

• Pregnancy experiences

• Childhood mortality

• Rural haiti

• Pregnancy complications

• Neonatal infant

Citation

Buresh C (2025) Pregnancy Experiences and Childhood Mortality in Rural Haiti. Med J Obstet Gynecol 13(2): 1197

INTRODUCTION

Haiti is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, with an underfunded national healthcare system [1], that makes quality health care access difficult for poor rural populations [2]. Despite the involvement of thousands of non-governmental health organizations in Haiti, there is little known about pregnancy risks and childhood mortality, particularly in rural areas. In 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 26 neonates died for every 1,000 live births, 49.5 infants died for every 1,000 live births, and 64.8 children under 5 died for every 1,000 live births [3]. These are the highest rates outside of Africa and Asia [4]. However, these numbers are only estimates based on administrative data, regional trends in other countries, and extrapolation from the last census [5]. Births and deaths often occur in the home in rural Haiti and may not be reliably reported to or recorded by the authorities. Indeed, the World Bank estimates that fewer than 10% of deaths are officially reported in Haiti [6].

Community Health Initiative Haiti (CHI) is a U.S.- registered not-for-profit organization working with rural communities in Central Haiti to improve health. As part of their ongoing needs assessments and to improve understanding of important health indices in their area, CHI conducted a survey of women in 5 partner communities. This study was done as a baseline at the beginning of their work with the intention of collecting data 10 years later to see how things had changed. That follow up data has been unobtainable. This paper provides a preliminary description of a subset of the results, including women’s experiences of pregnancy and delivery and the early health of their children.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A house-by-house survey was done in 5 small rural villages outside the city of Archaiae, Haiti in 2013. The selected villages are those served by Haitian Community Health Workers (CHWs) employed by CHI. Like 38% of rural Haiti, these villages are not connected by paved roads and only accessible by foot or 4x4 vehicle [7]. All villages were 5 kilometers or more from the nearest local health center, which is the case for 20% of rural Haitians [7]. This project was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Iowa; there was no formal local ethics review process available at the time of the study. The final survey instrument was modified from previously utilized CHI needs assessment surveys using feedback incorporated from community meetings. Before administration to the communities of interest, surveys were administered to local volunteers from other nearby communities and cognitive interviews were performed to get feedback on question clarity and understanding. After feedback was incorporated, the final survey instrument was administered to key adult informants in every household in the 5 villages studied.

Verbal consent was obtained in Haitian Creole (the participants’ native language) prior to initiating the survey, which was then administered verbally in Creole by the local CHW who recorded responses using paper and pencil. Households were able to decline to answer the survey altogether, and participants were able to decline to answer certain questions or to stop participating at any time without jeopardizing their ongoing care from the CHWs. Community health workers would visit the household as often as necessary to complete the survey for that house. GPS locations were recorded for every household surveyed.

Data were collected for all female participants over the age of 16 years on supplementary survey questions about menarche, marriage, contraception use, desired family size, pregnancies, deliveries, elective terminations, miscarriages and stillbirths, living children, childhood deaths, sexually transmitted diseases, sexual assault, and survival sex (intercourse in exchange for the necessities of living such as food, shelter, or protection.). It should be noted that elective termination (popularly known as “abortion”) has been illegal in Haiti since the adoption of the Napoleonic Code in 1835 [8]. If the women over 16 years old were not home when the survey was administered for their household, the primary adult household participant was asked the questions on their behalf. When this primary adult participant was unable or unwilling to answer questions about the absent women, the only information obtained for the absent woman was her age.

Any written comments were translated from Haitian Creole into English by a qualified translator. Data were transferred to an electronic database for storage and analysis. Descriptive statistics are reported, and bivariate tests (Pearson chi-square and Fisher’s exact test) were used to identify associations between maternal demographic characteristics and pregnancy outcome and childhood mortality. Due to the relatively large amount of missing data, imputation was not performed and results are an available case analysis with sample size for each analysis specified. Data were analyzed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute; Cary, NC).

RESULTS

A total of 685 households were surveyed from 5 villages. Information was collected on 941 women aged 16 years or older from 222 households. The remaining 463 households either were not home, declined to answer the questions, or did not contain any women over the age of 16 years. The ages of women surveyed ranged from 16 to 98 years old (mean 34 years old) (Table 1). A total of 2578 pregnancies were reported in 609 women, with a mean of 4 pregnancies per woman. On average, women were 20 years old (range 12 to 40 years old) at the time of their first pregnancy.

Table 1: Women surveyed ranged from 16 to 98 years old.

|

Table 1: Women surveyed ranged from 16 to 98 years old. |

||||

|

Category |

Range |

Mean (SE) |

Mode |

Median |

|

Age (years) n=941 |

16 to 98 |

33.7 (15.4) |

18 |

29 |

|

Age (years) at Menarche n=604 |

8 to 25 |

14.2 (2.0) |

13 |

14 |

|

Age (years) at First Pregnancy n=531 |

12 to 40 |

19.6 (3.8) |

17 |

19 |

|

Gravidity (# of pregnancies) n= 608 |

0-21 |

4.2 (3.2) |

3 |

3 |

Pregnancy Outcomes

Forty-three (9.0%) of the 478 women with information

provided on elective termination had undergone at least one termination (range 0 to 13 terminations per woman) for a total of 88 terminations (Table 2). Of the 511 women with information on stillbirth, 219 (42.8%) had at least one stillbirth (range 0 to 12 stillbirths reported per woman), for a total of 501 stillbirths. Ninety (18.7%) of the 481 women with information on miscarriage reported at least one miscarriage (range 0 to 5 miscarriages reported per woman) for a total of 139 miscarriages.

|

Table 2: Characteristics of Pregnancies and Delivery. |

||

|

Complications (n= 585) |

% |

|

|

Yes |

159 |

27.2 |

|

No |

426 |

72.8 |

|

Type of Complications* (n= 232) |

||

|

Infections |

91 |

39.2 |

|

Other |

54 |

23.2 |

|

Headaches and High Blood Pressure |

37 |

15.9 |

|

Bleeding |

22 |

9.5 |

|

Water Breaking Early |

14 |

6 |

|

Prematurity |

14 |

6 |

|

*Some women reported multiple complications. |

||

|

Location of Delivery (n=578) |

||

|

Home |

455 |

78.7 |

|

Hospital |

123 |

21.3 |

|

Person attending delivery (n=529) |

||

|

Midwife/Famn Sage |

325 |

61.4 |

|

Doctor |

157 |

29.7 |

|

Nurse |

9 |

1.7 |

|

Family |

37 |

7 |

|

Delivered alone |

1 |

0.002 |

We gathered data on pregnancy complications in 585 women; 159 of these women (27.2%) endorsed at least one of the 6 possible complications of pregnancy queried by the CHWs (Table 3). Infection was the most commonly reported pregnancy complication (91/585 women = 15.6%; 91/159 complications = 57.2%). Headache with high blood pressure (6.3%) of women, bleeding (3.6% of women), premature rupture of membranes (2.4% of women), and premature delivery (2.4% of women) were also reported.

|

Table 3: Pregnancy Outcomes (n= 2582). |

||||||

|

Category |

n |

Range |

Avg |

Mode |

Median |

Std. Dev |

|

Miscarriage |

139 |

0-5 |

0.289 |

0 |

0 |

0.734 |

|

Elective Termination |

88 |

1-13 |

0.184 |

1 |

1 |

2.236 |

|

Stillbirth |

501 |

0-12 |

0.98 |

0 |

0 |

1.686 |

|

Live births |

1772 |

0-10 |

3.18 |

1 |

3 |

2.053 |

|

Deaths after birth |

484** |

0-10 |

2.272 |

1 |

2 |

1.759 |

|

** 27 children not included in analysis because of incomplete data |

|

|||||

Overall, there were fifty-three participants (9.1%) noted to have birth complications not otherwise specified. There was no difference in age at first pregnancy when comparing woman who reported pregnancy problems versus those who reported no pregnancy problems (median age at first pregnancy with complications: 19 years, IQR: 17-21 versus no complications: 19 years, IQR: 17-21; p = 0.483) (Table 4).

|

Table 4: Overall Characteristics of Participating Women. |

||||

|

Category |

N* |

Median (IQR) |

Mean (SD) |

Range |

|

Age (years) |

941 |

29 |

33.7 (15.4) |

16 to 98 |

|

Age at Menarche (years) |

604 |

14 (13 – 15) |

14.2 (2.0) |

8 to 25 |

|

Age at First Pregnancy (years) |

531 |

19 (17 – 21) |

19.6 (3.8) |

12 to 40 |

|

Gravidity (# of pregnancies) |

608 |

3 (2 – 6) |

4.2 (3.2) |

0 to 21 |

|

IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation. *Sample size varies for each row. |

||||

The majority of women (78.7%) delivered their babies at home (Table 3). Over half (61.4%) of these home births were attended by a ‘famn sage’ (i.e., a “wise woman” who isa layperson with varying degrees of informal training who attends deliveries). A minority (31.4%) of these home births were attended by a physician or a nurse. Seven percent were attended by family members, and one woman delivered alone (Table 5). Women who reported pregnancy complications were more likely to have given birth in a hospital (34.6% vs. 15.5%, p <0.001) and have a doctor attend their birth (37.1% vs 22.8%, p=0.001) than women without complications. Of the women who delivered at home, complications were reported less often when there was a ‘famn sage’ present than when there was not (53.5% vs. 74.9%, p<0.001).

|

Table 5: Pregnancy Outcomes per Women. |

|||||

|

Outcome |

Total Events Reported |

Median (IQR) |

Mean (SD) |

Range |

Number of Women Responding N (response rate) |

|

Miscarriage |

139 |

0 (0 – 0) |

0.29 (0.73) |

0 to 5 |

481 (51.1%) |

|

Elective Termination |

88 |

0 (0 – 0) |

0.18 (0.89) |

0 to 13 |

478 (50.8%) |

|

Stillbirth |

501 |

0 (0 – 1) |

0.98 (1.69) |

0 to 12 |

511 (54.3%) |

|

Live births |

1772 |

3 |

3.18 (2.05) |

0-10 |

579 (61.5%) |

|

Deaths after birth |

484 |

0 (0 – 1) |

0.95 (1.60) |

0 to 10 |

509 (54.1%) |

|

IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation |

|||||

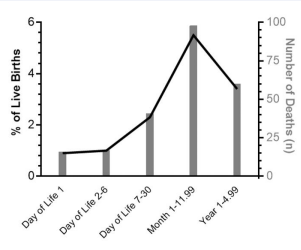

2578 deliveries were reported from 509 women. Outcomes were available on 2252 deliveries, while 326 (14%) were lost to follow-up. The 2252 deliveries include a total of 1772 living children and 480 (21.3%) child deaths. Information was obtained about the timing of death in 263/480 (54.3%) of the child deaths. Eighty- eight of these 263 cases (33.5%) occurred before 1 month of age, with more than half of these occurring in the first week (Table 6). Including these 88 neonatal deaths, 172 of the 263 cases (65.4%) of childhood death occurred before age 1 and 232 of them (88.2%) died by age 5 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Under Five Years Childhood Deaths.

Women reporting at least one child death (from day of life 1 through childhood) were slightly younger at the time of their first pregnancy than those with no child deaths (median age 18 (IQR: 17 to 20 ) vs. 19 (IQR: 17 to 22), p<0.001), more likely to have given birth at home (89.0% vs. 70.7%, p<0.001), and less likely to have had a doctor attend the birth (19.1% vs 30.9%, p=0.002) than women that did not have a child death.

|

Table 6: Characteristics of Delivery and Pregnancy Complications. |

||

|

|

n |

% |

|

Delivery Complications (N= 585) |

|

|

|

Any Pregnancy or Delivery Complication |

159 |

27.2% |

|

Type of Complication# |

|

|

|

Infections |

91 |

15.6% |

|

Headaches and High Blood Pressure |

37 |

6.3% |

|

Bleeding |

22 |

3.6% |

|

Water Breaking Early |

14 |

2.4% |

|

Prematurity |

14 |

2.4% |

|

Other |

54 |

9.2% |

|

Location of Delivery (N= 578) |

|

|

|

Home |

455 |

78.7% |

|

Hospital |

123 |

21.3% |

|

Person Attending Delivery (N=529) |

|

|

|

Midwife |

325 |

61.4% |

|

Doctor |

157 |

29.7% |

|

Nurse |

9 |

1.7% |

|

Family |

37 |

7.0% |

|

Delivered alone |

1 |

0.0% |

High-risk Child Mortality Subgroup: Among woman who reported at least one pregnancy (n=597), there were

0.95 average childhood deaths per woman (median: 0 [IQR: 0-1]). While most women (64.8%) did not report any child deaths, 10 percent of women (n=68) reported three or more child deaths. This high-risk group of 68 women represent only 13.4% of surveyed women who gave birth but suffered 61.0% (293/480) of all reported child deaths.

Although the high-risk group of women did have more pregnancies than women who had two or fewer children die (median 8 vs. 3 pregnancies per woman, p<0.001), when accounting for the higher number of overall pregnancies, they still had a slightly higher proportion of total pregnancies ending in death (21.4% vs. 16.7%, p<0.001). These high-risk women were more likely than their lower-risk parous neighbors to be married (25.0% vs. 16.3%, p=0.001), to deliver children at home as opposed to in a hospital (92.7% vs. 73.2%, p=0.002), and to have a ‘famn sage’ present at a home delivery (85.3% vs. 65.0%, p=0.001).

DISCUSSION

We found that one in five children born in rural Haitian villages died before adulthood and the vast majority of these deaths occurred before the age of 5. Two in five women in these villages had lost a child, with a small high- risk subgroup bearing the majority of this burden. While not directly comparable to WHO estimates, the rate of neonatal (4.2 vs 2.6%), infant (9.7 vs 5%), and under 5 deaths (13.1 vs 6.5%) in this study is nearly twice as high in each category as WHO data. This suggests there may be a bigger problem with neonatal and infant mortality in rural Haiti than publicly available data indicate.

Published data underestimates child and neonatal mortality for a number of well-known reasons. It may be due in part to disparate resources between urban and rural populations with associated differences in access to quality healthcare [9], safe water sources, and sanitation [10], among other things. Poor reporting and collection of vital statistics also likely contributes to these differences. According to the World Bank, 90.4% of urban births are registered in Haiti compared to 82% of rural births. Many deaths in Haiti go unreported, especially in rural areas, (9.5% of death registrations complete per the World Bank [11]), as people die at home and are buried without intersecting with the healthcare system or other government agencies clustered in cities. This underreporting of country-specific mortality data forces international bodies like the World Bank, UNICEF, and the

WHO to use statistical models based on regional trends to estimate childhood mortality, resulting in inaccurate accounting of mortality in Haiti.

Regarding maternal health, we found that the majority of women delivered at home and were attended by someone without formal training in delivery. Importantly, only 31.4% of the women in this group had a doctor or nurse present compared to the national statistics of 41.6% attendance by a doctor or nurse [12]. These home deliveries without the presence of a trained healthcare provider may be a contributing factor to the high rates of neonatal mortality. There were also high self-reported rates of pregnancy complications, making the lack of access to a formalized health care system in the perinatal period more troublesome. The high rates of pregnancy complications, stillbirths, neonatal deaths on the first day of life, and deaths within the first week are all remediable through better prenatal care, training in neonatal resuscitation, and early recognition and treatment of neonatal illness. Such poor outcomes have been addressed in other settings through widespread community education and incentivizing delivery at healthcare facilities equipped for obstetric emergencies [13], ensuring that facilities have the proper equipment for delivery and obstetric complications [14], and improving training on neonatal resuscitation [15], among other efforts.

In our cohort, women who had complications were more likely to deliver in the hospital, but the majority of them still delivered at home. It is unclear if the women chose to deliver at the hospital more often because they were having complications, or if complications were recognized more often in a hospital setting. Of those who stayed at home to deliver, women were less likely to report complications if they had a ‘famn sage’ present at delivery. Future work examining how women in this region choose to seek care in a hospital and a qualitative examination of healthcare provider’s perspectives on the frequency and cause of complications would be useful.

The number of elective terminations may have been under-reported. There were fewer women who answered questions about elective terminations than other questions, likely because of stigma and concerns about illegality. There were a remarkably high number of self-reported stillbirths. Some of these may be elective terminations that the women had reported as stillbirths [16,17]. For the stillbirths, it may not be possible to clarify whether these neonates would have survived with adequate resuscitation and, if so, what their health outcomes may have been.

It was notable that there was a subset of women with

significantly more child deaths than others. These high-

risk women tended to be older, multiparous (half of them had more than 8 pregnancies), economically insecure, and unable to access healthcare (e.g. home deliveries and ‘famn sage’ attendants). Despite the recurrence of poor pregnancy outcomes, these women were still less likely to deliver in the hospital or to have a doctor at their delivery. As such, multifactorial interventions targeted to high-risk women could greatly reduce infant and child mortality in this region of rural Haiti.

There are several limitations of this study. Primarily, this was a secondary analysis of a larger cross-sectional survey project assessing determinants of health and community health needs. As such, granular data at the level of individual pregnancies and deliveries were not obtained, and temporality between many risk factors and pregnancy outcomes was not established. There is no way to be certain that participants in this study were representative of the population as a whole. Missing data was a major limitation of this study, and due to the nature of the data and extent of missingness, we were not able to estimate the effect of the missingness on the estimates provided. Furthermore, possible socioeconomic and medical confounders (such as homelessness, varying degrees of poverty, interpersonal violence and family support) were not measured in this dataset, so associations between risk factors and outcomes for each pregnancy could not be identified.

Recall bias is a factor, as women were asked about pregnancies that happened across their lifespans, and some of the pregnancy questions were answered by friends and relatives when the woman was not present. Reporting bias may also be present, especially for sexual health questions querying potentially sensitive information. This is particularly concerning when considering the potential underreporting of some events such survival sex or abortions. Further, interviewers did not routinely ask clarifying or probing questions when participants gave confusing or conflicting responses. Taken in total, these data demonstrate associations only and cannot be utilized to assume cause and effect.

In conclusion, this work from a comprehensive house- to-house survey of 5 rural villages in Central Haiti provides unique and previously underappreciated insight into pregnancy experiences, childbirth, and early childhood for rural Haitian women and their families. According to these data, childhood death in rural Haiti may be much more common than what is reported through estimates from international bodies. Our study also highlights opportunities to improve these mortality rates in the perinatal period with programs that identify high risk pregnancies, improve prenatal and postnatal care, and establish early contact with the healthcare system for each maternal-infant dyad. Further prospective studies examining risk factors for complicated pregnancies and neonatal and early childhood mortality will help clarify how best to target such interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Community Health Workers Nola Fenelon, Widlyne Julien, Tamarra Joseph, and Guirliene Ripert for their help with data collection and their work in rural Haiti.

REFERENCES

- Cavagnero Eleonora Del Valle, Cros Marion Jane, Dunworth Ashleigh Jane, Sjoblom Mirja Channa. 2017. Better spending, better care: a look at Haiti’s health financing: summary report (English). Washington, DC: World Bank Group. 2017.

- Anna DG, Leslie Hannah H, Bitton Asaf, Jerome J Gregory, Thermidor Roody, Joseph Jean Paul, et al. Assessing the quality of primary care in Haiti”. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2017; 95: 182-190.

- WHO Global Health Observatory Data Repository, Data by Country: Haiti. 2019.

- CIA World Factbook, Country Comparison: Infant Mortality Rate:WHO Global Health Observatory Indicator Metadata Registry List. 2019.

- World Bank IBRD IDA Data, Completeness of Birth Records and World Bank IBRD IDA Data, Completeness of Death Registration with Cause- of-Death Information.USAID/HAITI Maternal and Child Health Portfolio Review and Assessment. 2008.

- The Spirits and the Law: Vodou and Power in Haiti, Ramsey, Kate, University of Chicago Press. 2014.

- WHO and UNICEF Joint Monitoring Program for Water Supply and Sanitation, Information on Haiti.World Bank Data, Information on Haiti.

- WHO. GHO Data Repository

- Serbanescu F, Goodwin MM, Binzen S, Morof D, Asiimwe AR, Kelly L, et al. Addressing the First Delay in Saving Mothers, Giving Life Districts in Uganda and Zambia: Approaches and Results for Increasing Demand for Facility Delivery Services. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2019; 7: S48-S67.

- Ngoma T, Asiimwe AR, Mukasa J, Binzen S, Serbanescu F, Henry EG, et al. Addressing the Second Delay in Saving Mothers, Giving Life Districts in Uganda and Zambia: Reaching Appropriate Maternal Care in a Timely Manner. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2019; 7: S68-S84.

- Mayer MM, Xhinti N, Mashao L, Mlisana Z, Bobotyana L, Lowman C, et al. Effect of Training Healthcare Providers in Helping Babies Breathe Program on Neonatal Mortality Rates. Front Pediatr. 2022; 10: 872694.

- Berry-Bibee EN, St Jean CJ, Nickerson NM, Haddad LB, Alcime MM, Lathrop EH. Self-managed abortion in urban Haiti: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2018.

- Tiziana Leone, Laura Sochas, Ernestina Coast. Depends Who’s Asking: Interviewer Effects in Demographic and Health Surveys Abortion Data. Demography. 2021; 58: 31-50.