Current Perspective for Atrial Fibrillation in Patient with Brugada Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review

- 1. Department of Cardiology, Universitas Padjajaran, Indonesia

Abstract

Brugada syndrome (BrS) is associated with SCD due to ventricular arrhythmia. The most common arrhythmic event in BrS is ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation (VT/VF). Atrial fibrillation (AF) is often documented as one of the SCN5A-positive mutation groups, the gene that may be found in BrS. Some studies say that Atrial Fibrillation is an atrial arrhythmia that is often found in Brugada Syndrome. In another study of 190 patients with Atrial Fibrillation, 11 were diagnosed with Brugada Syndrome, but did not experience Sudden Cardiac Death and 3 had Ventricular Fibrillation. The prognostic value of Atrial Fibrillation among Brugada Syndrome patients in relation to Sudden Cardiac Death has not been known until now. The prevalence of Atrial Fibrillation in Brugada Syndrome from previous studies ranged from 6% to 39%. The ESC guideline recommended that quinidine should be considered in patients with BrS who qualify for an ICD but have a contraindication, decline, or have recurrent ICD shocks. The latest ESC guideline recommended that ICD implantation is recommended in patients with BrS. The ESC guideline recommended that Catheter ablation of triggering PVCs and/or RVOT epicardial substrate should be considered in BrS patients with recurrent appropriate ICD shocks refractory to drug therapy. Recommendation of treatment of AF in BrS is limited, however double chamber ICD, quinidine, and PVI have shown some benefit in such patients. In this review we aimed to present the correlates Atrial Fibrillation and Brugada syndrome regarding pathophysiology, clinical manifestation, and management.

Keywords

• Brugada Syndrome

• Atrial Fibrillation

• SCN5A

• ICD

Citation

Iqbal M, Bunawan R, Karim K, Karwiky G, Achmad C (2025) Current Perspective for Atrial Fibrillation in Patient with Brugada Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Ann Cardiovasc Dis 9(1): 1041.

Citation

Iqbal M, Bunawan R, Karim K, Karwiky G, Achmad C (2025) Current Perspective for Atrial Fibrillation in Patient with Brugada Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Ann Cardiovasc Dis 9(1): 1041.

INTRODUCTION

Brugada syndrome (BrS) is associated with SCD due to ventricular arrhythmia. The most common arrhythmic event in BrS is ventricular tachycardia/ ventricular fibrillation (VT/VF). However, other rhythm disturbances such as AF is common finding in BrS [1]. The presence of AF in BrS has also been associated with a more malignant course. Atrial fibrillation (AF) is often documented as one of the SCN5A-positive mutation groups, the gene that may be found in BrS [2,3]. Age-related development of fibrosis and progressive slowing of atrial conduction due to a 50% reduction in the expression of atrial Connexin 43, was also documented in patient with SCN5A loss of function mutation, suggesting other genetic sharing mechanism in AF and BrS [4]. Some studies say that Atrial Fibrillation is an atrial arrhythmia that is often found in Brugada Syndrome. The prevalence of Atrial Fibrillation in Brugada Syndrome from previous studies ranged from 6% to 39%3. Although structural heart disease is the most common etiology of AF, other mechanism should not be overlooked since AF may be a combination of multiple factors, genetic or acquired, that may impact upon autonomic function, atrial structure, and conduction velocities or other unknown factors [2]. It is suspected that there is an interruption of electrical conduction in the atrium and ventricle which is indicated to cause further disease. The risk of SCD increase in patient with recurrent syncope, family history etc. However, the prognostic value of Atrial Fibrillation among Brugada Syndrome patients in relation to Sudden Cardiac Death has not been known until now [3]. Given the high prevalence of AF in BrS and the unrevealed share link between those arrhythmic entities, this review article aims to provide a comprehensive review on AF in BrS.

Atrial Fibrillation coexist Brugada Syndrome

The results of a meta-analysis of 6 studies showed that there was a relationship between the occurrence of Atrial Fibrillation and an increased risk in patients with Brugada Syndrome [3]. A study conducted by Brugada Laten et al., showed that from the results of genetic tests in patients with Atrial Fibrillation, two positive patients had mutations in the SCN5A and SNP genes within SCN10A. In a study conducted by Brugada Laten et al. on Atrial Fibrillation patients under the age of 45 without previous risk factors, out of the 74 individuals studied, 13 people (16.7%) were found to have an ECG pattern of Brugada Syndrome Type 1. This proportion is higher than the previous study which shows that Atrial Fibrillation may be associated with the incidence of Latent Brugada Syndrome. In another study of 190 patients with Atrial Fibrillation, 11 were diagnosed with Brugada Syndrome, but did not experience Sudden Cardiac Death and 3 had Ventricular Fibrillation5. Atrial fibrillation occurs spontaneously in up to 30% of Brugada syndrome patients and is usually associated with a poor diagnosis (Figure 1).

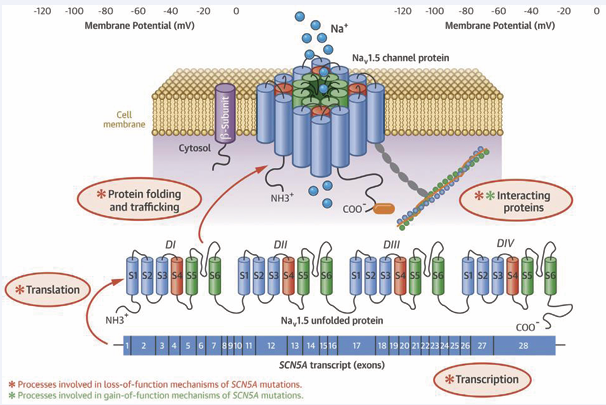

Figure 1: SNC5A, Nav1.5, and the underlying Molecular Mechanism of SCN5A Mutation on Disease.

Pathophysiology Atrial Fibrillation in Brugada Syndrome

Several genes have been implicated in the pathogenesis of BrS, the most common being SCN5A (with more than 100 mutations) (Figure 2), which can be found in 20% to 30% of patients; rare variants in genes affecting the sodium current (SCN1B, SCN10A) and calcium current (CACNA1C, CACNA2D1, and CACNB2B) have been described in a minority of patients [5].

Figure 2: Pathophysiology of Atrial Fibrillation in Brugada Syndrome.

Based on the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines regarding the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias, it is recommended to examine the SCN5A gene for all patients who have proven Brugada syndrome [6]. Since in humans, the cardiac sodium channel (SCN5A) gene has a role to depolarize the cardiac action potential. Mutations in the SCN5A gene can be found in Long QT syndrome, Sick sinus syndrome, cardiac conduction defects, BrS and AF [7]. So far, there are 23 genes associated with Brugada syndrome, so several studies refer to hypotheses regarding pathophysiology related to genes, namely those genes can be divided according to whether they affect the sodium current INa (SCN5A, SCN10A, GPD1L, SCN1B, SCN3B, RANGRF, SCN2B, PKP2, SLMAP, and FGF12), the potassium current IK (KCNJ8, KCNH2, KCNE3, KCND3, KCNE5, KCND2, SEMA3A, and ABCC9), or the calcium current ICa (CACNA1C, CACNB2B, and CACNA2D1) [8]. While in AF, the genetic mutation that was found to increase the risk of AF development includes the potassium current gene (ABCC9, HCN4, KCNA5, KCND3, KCNE1, KCNE2, KCNE3, KCNE4, KCNE5, KCNH2, KCNJ2, KCNJ5, KCNJ8, KCNN3, and KCNQ1), the sodium current gene (SCN3B, SCN4B, SCN5A, and SCN10A), and other genes that involve in gap junction protein, nuclear pore complex, etc. (GJA5, NUP155, E169K, CASR, PITX2, NURL1, PRRX1, CAV1, CUX2, ZFHX3) [9]. Molecular structure of the SCN5A transcript with its 28 exons, which is translated into the a-subunit (Nav1.5) of the cardiac sodium channel. Mechanisms by which SCN5A mutations cause Nav1,5 loss-of function and gain of function involve disruption in several molecular process including gene transcription and translation, Nav1.5 folding and trafficking and Nav1.5 interaction with the regulatory proteins. In addition, SCN5A mutations may cause changes in channel gating [10]. 3 of 10 sodium channel-related gene (SCN5A, and SCN10A, SCN3B) that has been known to cause BrS also increase the risk of AF. 5 out of 8 potassium channel-related gene (ABCC9, KCNH2, KCNE3, KCND3, and KCNE5) that has been known gene to cause BrS also increase the risk of AF. While none of the calcium-channel-related gene in BrS was found to increase the risk of AF among those genes, SCN5A mutation is the most commonly studied since it is most commonly found in BrS patients [2,9]. The pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation in Brugada syndrome includes interactions between triggers, and arrhythmogenic substrates and factors that modulate the autonomic nervous system or inflammation. The circadian pattern of atrial fibrillation occurs mostly at night, potentially influencing Vagal stimulation in arrhythmogenesis, Vagal stimulation can reduce atrial conduction velocity and shorten the refractory period thus facilitating the induction of Atrial Fibrillation [4]. Atrial structural anomalies can cause delays in interatrial conduction within Brugada Syndrome and Atrial Fibrillation patients. These atrial changes usually serve as a substrate for reentry to occur for atrial tachyarrhythmias. It takes two fundamental conditions for reentry to occur in arrhythmias, namely: anatomical or functional block and excited gaps throughout the area. Slow atrial conduction causes reentry in atrial tachyarrhythmias that can explain cause of the higher incidence of tachyarrhythmias in patients with Brugada syndrome3. Bradycardia and vagal can decrease calcium flow and ultimately contribute to ST segment elevation and pro-arrhythmias. To date, based on a collection of several studies in Brugada syndrome patients, ST segment elevation in leads V1 to V3 are due to delayed conduction flow along with delayed activation, increased number of end potentials, and altered repolarization duration [11]. Abnormalities of the conduction and repolarization systems are also associated with the SC5NA gene mutation, which is the gene responsible for the sodium channel subunit. This abnormality produces ECG waves with RBBB appearance and ST segment elevation on the right precordial12. Loss-of-function SCN5A mutations can have opposite effects on sodium channel inactivation with different effects on repolarization. Inactivation of this sodium channel causes a disturbance of the phase 0 action potential, a continuous abnormality of the sodium current affects the depolarization phase, repolarization becomes abnormal. Diagnostic criteria for diagnosing Brugada syndrome show that there is an abnormal structure in the myocardial muscle. This structural change can trigger a slow but progressive remodeling in both the ventricles and atria [12,13]. The process of atrial remodeling causes electrical disturbances between the muscle fibers and the conduction fibers of the diatria and is a precipitating factor as well as a perpetuating factor in the occurrence of atrial fibrillation. This electroanatomical substrate facilitates the reentry circuit that will perpetuate the arrhythmia. One study reported a shortened atrial effective refractory period in the first days of atrial fibrillation. The main mechanism underlying the shortening of the recoil period is down-regulation of potassium inflow (through L-type channels) and up-regulation of potassium currents. Shortening of potassium currents mediated by L-type calcium channels caused reduced potassium inflow. This mechanism could be the basis for the arrhythmogenesis in Brugada syndrome [11].

Vagal stimulation of atrial fibrillation reduces atrial conduction velocity and shortens the refractory period. The onset of atrial fibrillation is often preceded by fluctuations in autonomic tone; vagal stimulation reduces atrial conduction velocity and shortens the refractory period. SCN5A mutation has the potential to determine the slowing of intatrium electrical conduction. Intraatrial conduction delay is significantly increased in patients with diagnosed Brugada syndrome and Atrial Fibrillation, suggesting that atrial myocardial conduction is impaired and confirming increased atrial susceptibility in patients with Brugada Syndrome where abnormal atrial conduction may be the electrophysiological basis for induction of Atrial Fibrillation. Patients with Brugada syndrome have a higher incidence of interatrial block. (A) In general, has been extensively and current understanding includes an interplay of triggers, arrhythmogenic substrate, and modulating factors such as the autonomic nervous system or inflammation. (B) Brugada syndrome has typical autosomal dominant transmission with variable penetrance [4].

Clinical Manifestation of Atrial Fibrillation in Brugada Syndrome

The clinical presentation of atrial fibrillation varies widely, ranging from asymptomatic to cardiogenic shock or cerebrovascular events. Patients often complain of mild symptoms such as palpitations, fatigue or low tolerance for physical activity, presyncope or syncope and dizziness. Next, the symptoms that arise in Brugada Syndrome are symptomatic and asymptomatic. The majority of asymptomatic patients (about 63%) have just been diagnosed with Brugada syndrome. Symptomatically, the most common symptoms are fainting, convulsions, and the presence of VT/VF, even to sudden cardiac death if an arrhythmia persists [1,14]. Based on data from SABRUS, the incidence of fainting and SCD in Brugada syndrome is around 17 - 42%. The age that is associated with SCD symptoms in adulthood are most frequent in men [14]. Atrial arrhythmias are now increasingly recognized in Brugada syndrome with an incidence rate of around 6% and which have been reported as many as 38% [3].The atrial arrhythmia that often occurs in Brugada syndrome is Atrial fibrillation with an incidence rate of 10-20% and this is often associated with a risk of fainting and sudden cardiac death1. Atrial fibrillation is one of the mutations in the SCN5A gene which is one of the causes of Brugada Syndrome. This could show a relationship between the two, but this research is still unclear.

Management of Atrial Fibrillation in Brugada Syndrome

The principle of management in BrS is to prevent cardiovascular mortality from life-threatening arrhythmia. Recommendation on treatment of AF in BrS is limited. The ESC guideline recommended that quinidine should be considered in patients with BrS who qualify for an ICD but have a contraindication, decline, or have recurrent ICD shocks. Isoproterenol infusion should be considered in BrS patients suffering electrical storm. The ESC guideline recommended that class I drugs are contraindicated. Side effects due to class I-C AADs have been potentially documented and these agents today are not considered as first-line therapy. Most AADs with sodium channel blocking properties may increase transmural dispersion of refractoriness, and subsequently may expose a patient with BrS to the development of malignant arrhythmias. Amiodarone (a class III AAD) has been demonstrated to be ineffective in prolonging survival in BrS. Sotalol may cause bradycardia, facilitating the induction of VAs, while beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers may increase transmural dispersion of repolarization and ECG ST-segment elevation6. Quinidine, an AAD with blocking activity in the Ito and IKr currents, has been shown to prevent phase II re-entry and ventricular fibrillation (VF) in in vitro studies of BrS. AADs that are considered effective in preventing malignant arrhythmias in BrS such as quinidine, may also be useful in AF treatment. Quinidine, with Ito blocking properties, may restore normal epicardial action potential dome morphology, preventing phase 2 re-entry [15]. A study by Giustetto et al., analyzed the prevalence of atrial arrhythmias and the effectiveness of hydroquinidine in Brugada syndrome patients with no recurrence of AF after drug therapy for an average of 28 month [16]. Then, from a study conducted by Kusno et al., AF patients treated with quinidine and bepridil for recurrent VF episodes did not experience AF episodes while using this drug [17].

ICD implantation remains the gold standard therapy proven to reduce mortality in BrS. The latest ESC guideline recommended that ICD implantation is recommended in patients with BrS who: (a) Are survivors of an aborted CA and/or (b) Have documented spontaneous sustained VT (class I). ICD was used as secondary prevention for patient with BrS (class I). For primary prevention, ICD can be useful or can be considered in patient with spontaneous type I ECG and history of syncope judged to be caused by ventricular arrhythmias or inducible VF on EP study. Systematic review by El-Battrawy et al., assimilated a total of 11 studies, analyzing the outcome in 747 BrS patients receiving ICD. Although ICD is the mainstay non-pharmacological treatment of BrS, data regarding its use in AF patients are limited. ICD therapy is not recommended when VF or VT is amenable to surgical or catheter ablation such as in AF. Catheter ablation in AF have been proven to successfully treat AF episode, implying that ICD may prevent SCD in BrS but not prevent AF in BrS. The impact of ICD on all-cause mortality in AF patients when compared to goal-directed medical therapy is unclear15. The ESC guideline recommended that Catheter ablation of triggering PVCs and/or RVOT epicardial substrate should be considered in BrS patients with recurrent appropriate ICD shocks refractory to drug therapy. Catheter ablation in asymptomatic BrS patients is not recommended [15]. Meta analysis by Rodríguez-Mañero et al., involved 49 studies that evaluated interventional treatment for AF in the BrS population using pumonary vein isolation (PVI). A total of 49 patients with BrS and AF were included. 38 patients were implanted with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD) at baseline, and of them, 39% suffered inappropriate shocks for rapid AF [18]. Other study by Bisignani et al compared 60 patients AF with BrS and 60 patients AF without BrS on long term outcome after PVI. After a mean follow-up of 58.2±31.7 months, freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias was achieved in 61.7% in the BrS group and in 78.3% in the non-BrS group (log-rank P=0.047). In particular, freedom from AF was 76.7% in the BrS group and in 83.3% in the non-BrS. In the BrS group, 29 patients (48.3%) had an ICD and 8 (27.6%) had a previous ICD-inappropriate shock for fast AF. Pulmonary vein isolation in patients with BrS was associated with higher rate of arrhythmic recurrence [14].

CONCLUSION

One type of gene, a mutated SCN5A, can change the function of the sodium channel so that it affects depolarization and repolarization work to become abnormal and can trigger arrhythmia, one of which is atrial fibrillation. Due to its genetic sharing with AF through SCN5A gene mutation, the risk of AF in BrS is higher than that in normal population. AF indicates a more severe BrS and its occurrence may increase the rate of inappropriate shock. Both BrS and AF had underlying genetic predisposition that include the sodium, potassium, and calcium channel gene. Some of the gene that found to be associated with BrS were also found in AF, thus they may share similar genetic mechanism. Even though the BrS is a ventricular arrhythmia, but the presence of AF may indicate that gene expression predisposing to BrS has already manifested. It is thought that BrS and AF are developed as manifestation of genetic mutation, that may explain the genetic share link between the two arrhythmic entities. Recommendation of treatment of AF in BrS is limited, however double chamber ICD, quinidine, and PVI have shown some benefit in such patients.

REFERENCES

- Brugada J, Campuzano O, Arbelo E, Sarquella-Brugada G, Brugada R. Present Status of Brugada Syndrome: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72: 1046-1059.

- Sieira J, Brugada P. The definition of the Brugada syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2017; 38: 3029-3034.

- Kewcharoen J, Rattanawong P, Kanitsoraphan C, Mekritthikrai R, Prasitlumkum N, Putthapiban P, et al. Atrial fibrillation and risk of major arrhythmic events in Brugada syndrome: A meta-analysis. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2019; 24: e12676.

- Vlachos K, Mascia G, Martin CA, Bazoukis G, Frontera A, Cheniti G, et al. Atrial fibrillation in Brugada syndrome: Current perspectives. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020; 31: 975-984.

- Ghaleb R, Anselmino M, Gaido L, Quaranta S, Giustetto C, Salama MK, et al. Prevalence and Clinical Significance of Latent Brugada Syndrome in Atrial Fibrillation Patients Below 45 Years of Age. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020; 7: 602536.

- Zeppenfeld K, Tfelt-Hansen J, de Riva M. ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death Developed by the task force for the management of patients with death of the European Society of Cardiology ( ESC ) Endorsed by the. Eur Heart J. Published online 2022; 1-130.

- Deb B, Ganesan P, Feng R, Narayan SM. Identifying Atrial Fibrillation Mechanisms for Personalized Medicine. J Clin Med. 2021; 10: 5679.

- Gourraud JB, Barc J, Thollet A, Le Scouarnec S, Le Marec H, Schott JJ, et al. The Brugada Syndrome: A Rare Arrhythmia Disorder with Complex Inheritance. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2016; 3: 9.

- Vutthikraivit W, Rattanawong P, Putthapiban P, Sukhumthammarat W, Vathesatogkit P, Ngarmukos T, et al. Worldwide Prevalence of Brugada Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2018; 34: 267-277.

- Wilde AAM, Amin AS. Clinical Spectrum of SCN5A Mutations: Long QT Syndrome, Brugada Syndrome, and Cardiomyopathy. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018; 4: 569-579.

- Blok M, Boukens BJ. Mechanisms of Arrhythmias in the Brugada Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2020; 21: 7051.

- Li KHC, Lee S, Yin C. Brugada syndrome: A comprehensive review of pathophysiological mechanisms and risk stratification strategies. IJC Hear Vasc. 2020; 26: 100468.

- Aziz HM, Zarzecki MP, Garcia-Zamora S, Kim MS, Bijak P, Tse G, et al. Pathogenesis and Management of Brugada Syndrome: Recent Advances and Protocol for Umbrella Reviews of Meta-Analyses in Major Arrhythmic Events Risk Stratification. J Clin Med. 2022; 11: 1912.

- Bisignani A, Conte G, Pannone L, Sieira J, Del Monte A, Lipartiti F, et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Pulmonary Vein Isolation in Patients With Brugada Syndrome and Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022; 11: e026290.

- Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström- Lundqvist C, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio- Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): Eur Heart J. 2021; 42: 373-498.

- Giustetto C, Cerrato N, Gribaudo E, Scrocco C, Castagno D, Richiardi E, et al. Ferraro A. Atrial fibrillation in a large population with Brugada electrocardiographic pattern: prevalence, management, and correlation with prognosis. Heart Rhythm. 2014; 11: 259-265.

- Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death. 2018; 138.

- Rodríguez-Mañero M, Kreidieh B, Valderrábano M, Baluja A, Martínez- Sande JL, García-Seara J, et al. Ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with Brugada syndrome: A systematic review of the literature. J Arrhythm. 2018; 35: 18-24.