Recurrent Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection with LAD Occlusion: A Case Report of Initial and Subsequent Episode

- 1. Department of Cardiology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, UK

Abstract

Background: Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (SCAD) is an acute coronary event of uncertain origin. SCAD occurs when the coronary artery wall dissects non-traumatically and non-atherosclerotically, leading to the formation of an intramural hematoma or intimal tear, ultimately compressing and restricting the true lumen, or even occluding it. The management of SCAD remains controversial despite modern imaging techniques. In addition to supportive drug therapy, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is another option that can be used as an effective treatment modality.

Case summary: This is a 51-year-old patient with a history of SCAD initially diagnosed in 2019 after presenting with chest pain and anterior ST elevation on ECG. At that time, she was successfully treated by stenting, resulting in symptom resolution. Five years later, she represented with typical cardiac chest pain and ECG suggestive of anterior wall acute myocardial infarction, accompanied by a significant elevation in cardiac enzymes. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) revealed a haematoma with SCAD formation extending from the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) to the left main stem (LMS). Initial medical management did not suffice, and subsequently percutaneous intervention was required.

Discussion: This case report uniquely demonstrates an example of a recurrent SCAD presentation in which short term conservative therapy was not sufficient and subsequent percutaneous intervention was undertaken within hours of initial presentation. Aside from avoiding triggers and optimising hypertension levels, currently there is lack of data for secondary prevention of SCAD.

Keywords

• Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD); Percutaneous coronary Intervention; Cutting Balloon; Intramural Hematoma; Intravascular Ultrasound (IVUS)

CITATION

Chatwin G, Costa SG, Al-Shatanawi A, Barbosar LL, Shahid F. (2025) Recurrent Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection with LAD Occlusion: A Case Report of Initial and Subsequent Episode. Ann Cardiovasc Dis 9(1): 1038.

INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (SCAD) is a non-traumatic, nonatherosclerotic tear in the coronary artery wall which leads to collection of blood within the tunica media, forming an intramural hematoma and compressing the true lumen, triggering ischaemia and acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Two proposed pathophysiological processes are the “inside-out” hypothesis, where damage to endothelium allows blood to enter from the true lumen to the subintimal space, and “outside-in”, where the haematoma arises spontaneously in tunica media [1]. It is increasingly recognized as an important cause of myocardial infarction – primarily affecting young to middle-aged women with a reported mean age of 51.8 years, especially those without conventional cardiovascular risk factors [2]. Unlike atherosclerosis, SCAD occurs in arteries that are typically smooth and free from plaque buildup, resulting in fragile vessel walls that can experience extensive dissection upon rupture. SCAD remains under-recognized yet may account for up to 2–4% of all ACS cases [3], and as much as one-third of ACS presentations in young women [1].

Risk factors associated with SCAD include postpartum/ childbirth, rheumatological diseases, fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), connective tissue disease, extreme physical exertion or intense emotional stress [2]. More isolated cases were reported with sympathomimetic drugs (cocaine), valvasa-like activities (retching), and cancer treatment (fluorouracil and radiotherapy) [4-6].

The clinical presentation of SCAD often mirrors that of ACS, including chest pain, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-STEMI, arrhythmias, and, in severe cases, sudden cardiac death [7]. Conservative management is preferred due to the potential risks associated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), including dissection propagation and complications in navigating fragile arterial walls [7]. PCI may be necessary in cases of severe ischemia or hemodynamic instability. Recent advancements such as the use of small cutting balloons to fenestrate the intima and drain the hematoma, offer innovative options, though their application remains limited.

The aim of this case report is to highlight an unusual presentation of SCAD and describe a successful approach using a 4mm cutting balloon to release the hematoma leading to the resolution of symptoms in the context of acute ST elevation MI and failure of initial conservative measures.

CASE PRESENTATION

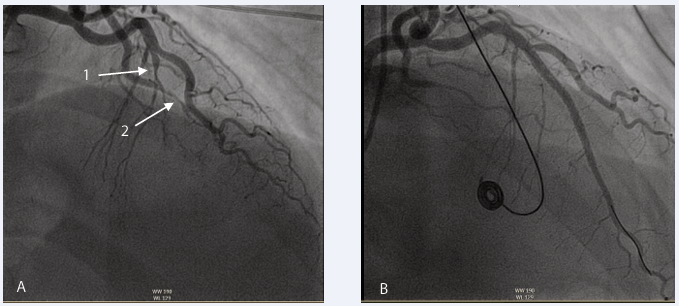

A 51-year-old patient first presented to the cardiology department in October 2019 with acute onset chest pain. Primary PCI pathway was activated due to her anterolateral ST elevation on 12-lead ECG. Notably, her cardiovascular risk factors included only smoking and raised BMI. Examination revealed a diaphoretic, tachycardic patient, but was otherwise unremarkable. Blood pressure was maintained. Coronary angiography showed an occlusion in the mid-left anterior descending (LAD) artery and a spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) not linked to coronary artery disease. She was treated percutaneously with drug eluding stents (DES), discharged, and remained asymptomatic during follow-up visits (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1: Coronary angiography from initial presentation in 2019. (A) Anteroposterior Cranial view. Arrow 1 highlights SCAD in mid part of left anterior descending after the first diagonal branch, arrow 2 demonstrates SCAD in distal marginal branch. (B) Right anterior oblique cranial view post PCI to mid left anterior descending (LAD) artery following deployment of 2 drug eluting stents (DES)

Table 1: Admission of Patients in Different Timeline

|

Dates |

Events |

|

|

11 October 2019 |

Admitted with ST elevation MI |

Coronary angiography revealed a complete occlusion of the mid- left anterior descending (LAD) artery with TIMI 0 flow in the distal segment. Additionally, spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) was identified in the distal marginal branch. PCI to LAD undertaken |

|

7 November 2024 - AM |

Chest pain with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Symptoms resolved spontaneously without treatment. |

First coronary angiogram showed mild in-stent restenosis (ISR), without any blocked artery. IVUS revealed proximal LAD hematoma. Conservative treatment was initiated. |

|

7 November 2024 - PM |

Later that same day, whilst in the coronary care unit (CCU), the patient experienced recurrent chest pain, with the ECG again showing STEMI in the anterolateral leads. |

Second coronary angiogram revealed proximal LAD totally occluded with no flow into the distal segment. Therefore, 4.0x12 Wolverine Cutting balloon was used to release the hematoma and 2 Drug eluting stents from LMS to mid LAD stents used. |

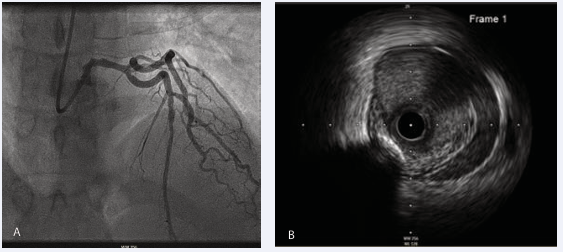

In November 2024, she returned with chest pain, anterior ST elevation on ECG. She was taken directly to the cardiac catheterization lab where angiography showed TIMI 3 flow in the left main stem (LMS) and LAD but an appearance in keeping with haematoma formation in the LAD. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) showed haematoma in the proximal LAD extending to the LMS (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Following presentation in 2024. (A) Anterio posterior cranial imaging during coronary angiography demonstrated features in keeping with in-stent restenosis. (B) Intravascular Ultrasound (IVUS) confirmed haematoma in the proximal LAD.

However, the patient’s chest pain settled, and ECG normalized - thus a decision for medical management was made.

TREATMENT

Whilst on the coronary care unit post initial coronary angiography, the patient developed new chest pain and ST-elevation in the anterolateral leads (Figure 3).

Figure 3: ECG whilst in CCU showed ST-elevation in anterolateral leads with reciprocal changes in inferior leads

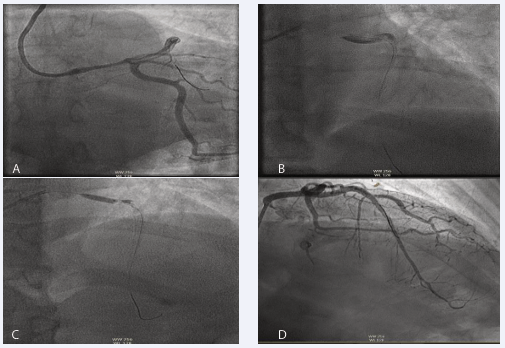

She was urgently returned to the catheter lab, where the right radial artery was accessed using a 6 French sheath and VL 3.5 guide was taken. Coronary angiography showed proximal LAD occlusion with contrast “hang-up,” indicating haematoma, and progression of the SCAD, requiring further treatment.

A run-through wire was advanced into the LAD without complications, and a 4.0 x 12 mm Wolverine Cutting balloon was used to release the hematoma and restore TIMI 3 flow.

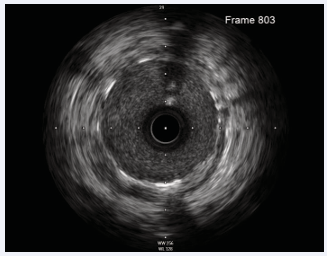

A 3.5 x 36 mm Biomatrix stent was deployed to cover the proximal LAD, overlapping with the previous mid-LAD stent. IVUS confirmed LAD diameter at 4.5 mm and a 4.75 mm diameter at the left main stem. (Distally with previous LAD stent and proximally to cover whole LMS.) (IVUS measurement). A 3.5 x 29 mm Biomatrix stent was deployed to overlap with the ostium of the left main stem. A 4.5 mm NC balloon was used at high pressure from just distal to the diagonal to the LAD ostium (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 4: Return to cath lab. (A) Anterio posterior caudal view showed SCAD in LAD back to LMS with no flow in distal LAD. (B) Anterio posterior Cranial showed no flow in LAD (Dye hang up). (C) Wolverine cutting balloon 4.0x12 at 6 atm pressure was used to release the hematoma in LMS and Proximal LAD. (D) The result after PCI with 2 Drug eluting stents from LMS down to mid LAD.

Figure 5: Final IVUS post stent deployment shows well opposed and expanded stents with resolution of haematoma

DISCUSSION

SCAD is an important differential diagnosis to take into consideration in female patients with chest pain. This is especially significant in those <50 years old and with a previous history of SCAD, which accounts for up to 35% of ACS cases in women. This figure is also considered to be underestimated since it is limited by dependence on administrative database, lack of clinical data or limitation during diagnostic criteria for patients who died before diagnosis or without coronary imaging.

The definition and predictors of recurrent SCAD are often mislabeled due to variable classification factors. Many studies classify recurrent SCAD as an apparent new dissection in a location that does not suggest the extension of a prior SCAD alone or associated with elevated ACS symptoms and biomarkers usually within 7 days of presentation. However, timeframe is not a precise factor in classifying this entity. When recurrence is considered, clinical consideration of new myocardial ischemia (symptoms, ECG and biomarkers) associated with invasive imaging are advised to be followed to differentiate an extension to a new SCAD.

Cases so far have reported recurrence of SCAD majority seen within 1 year of first presentation, such as a study of Krittanawong et al., 2020 showed 26.9% of his database of patients admitted with primary diagnosis of SCAD (1836 in total) with recurrent SCAD within 1 year (74% female, 74% <65 years old).

This case report uniquely demonstrates an example of an atypical recurrent SCAD presentation in which intravascular imaging in the form of IVUS was used to confirm the diagnosis and resolution of intramural haematoma and symptoms. Given the suspicion of acute coronary ischemia, this patient warranted revascularization despite initial attempts at a “conservative” approach. Aside from avoiding triggers and optimizing hypertension levels, currently there is lack of data for secondary prevention of SCAD.

CONCLUSION

In summary, there is a limited indication regarding secondary prevention of SCAD, which makes the optimization of diagnosis and treatment essential for improving patient outcomes. Further studies regarding follow-up in patients with recurrent SCAD are necessary to assess the efficacy of this method

REFERENCES

- Hayes S, Tweet M, Adlam D, Esther S, Rajiv G, Joel E, et al. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020; 76: 961-984.

- Saw J, Starovoytov A, Humphries K, Kunal M, Neil B, Andrea L, et al. Canadian spontaneous coronary artery dissection cohort study: in- hospital and 30-day outcomes, Eur Heart J. 2019; 40: 1188-1197

- Adlam D, Alfonso F, Maas A, Vrints C, Writing C. European Society of Cardiology, acute cardiovascular care association, SCAD study group: a position paper on spontaneous coronary artery dissection, Eur Heart J. 2018; 39: 3353-3368.

- Brunton N, Best PJM, Skelding KA, Emily EC. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (SCAD) from an Interventionalist Perspective. Curr Cardiol. 2024; 26: 91-96.

- Mujtaba S, Srinivas VS, Taub CC. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection causing acute myocardial infarction in a 62-year-old postmenopausal woman without co-morbidities: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2012; 28: 430.

- Hart K, Patel S, Kovoor J. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection Associated with Anal Cancer Management with Fluorouracil and Radiotherapy. Cureus. 2019; 11: 4979.

- Aziz S. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection. ESC E-j Cardiol Prac. 2017; 14