Knowledge and Readiness to Uptake Prenatal Genetic Screening among Antenatal Clinic Attendees Pre and Post Intervention in a Nigerian Teaching Hospital: A Pilot Study

- 1. Public health Nursing, University College Hospital, Ibadan , Nigeria

- 2. Department of Nursing, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

Abstract

Background: Prenatal Genetic Screening (PGS) refers to multiple procedures to identify congenital and genetic abnormalities prior to birth. Prenatal genetic screening is offered to all patients early in pregnancy in developed countries, but it has yet to be incorporated into government hospitals in Nigeria. It is therefore imperative to assess pregnant women’s knowledge and their readiness to uptake PGS in Nigeria.

Methods: A quasi-experimental one-group pre and post intervention was adopted Random-sampling method was used to select 35 pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in Lagos University Teaching Hospital. A structured questionnaire was utilised to collect information before and after a midwife led educational intervention. Data collected was managed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 25 software. Descriptive statistics was used to analyse and present variables. Mann Whitney U was used to test associations between variables because the data does not have normal distribution p = 0. 05.

Results: The mean age of the participants was 32.23 ± 4.99 years. Most of the participants were Christian 27 (77%), a higher percentage 16 (45.7%) of them were primigravida and only 2 (5.7%) reported ever having a child with congenital malformation/birth defect. The majority of participants (97.1%) were unaware of the different methods of PGS except for ultrasound, which was, the main method identified. The majority of the participants (62.9%) strongly agreed that PGS is valuable for all pregnant women and that it should be included as part of health education during antenatal clinic at post-intervention. The study revealed a significant difference in the median knowledge score of the participants at pre and post intervention (p value = 0.016) the median knowledge score at pre-intervention was 27 (IQR 24 – 31) while the median score at post intervention was 29 (IQR 27 -31). There was no significant difference in the median perception score of the participants at pre and post intervention stage (p-value = 0.293). In addition, the study revealed a significant difference in the proportion of participants who are ready to uptake PGS at pre intervention (17.1%) and post intervention stage (40%) (P-value = 0.039).

Conclusion: The result indicates that midwife-led educational intervention improved pregnant women’s knowledge of PGS and promote their readiness for uptake. Although perception score after intervention showed a slight improvement, it was not statistically significant.

Recommendation: Health care providers need to provide necessary information to pregnant women on the benefits of PGS and its implication to the health of their foetus. The readiness of pregnant women will inform stakeholders on the need to formulate policy that can guide provision of PGS services in Nigeria.

Keywords

• Prenatal Genetic

• Screening

• Knowledge

• Perception

• Preparedness

• Pregnancy

CITATION

Adigun AS, Ojo IO, Adejumo PO (2024) Knowledge and Readiness to Uptake Prenatal Genetic Screening among Antenatal Clinic Attendees Pre and Post Intervention in a Nigerian Teaching Hospital: A Pilot Study. Ann Nurs Pract 11(1): 1136.

INTRODUCTION

Background to the Study

Globally, about 240,000 neonatal deaths and 170,000 deaths of children between ages one month and 59 months occur yearly as a result of congenital anomalies [1] while those that survived face significant physical, psychological and emotional disabilities [2]. This leads to disappointment and grieving among women who had hoped for a normal development of a foetus and a healthy child. Perinatal mortality remains unacceptably high in Nigeria with fresh stillbirth accounting for most of these deaths and from autopsy, congenital malformations contribute significantly to these prevailing high perinatal mortalities [3,4]. In addition to this, it has been documented that birth defects are responsible for miscarriages, pre-term deliveries and stillbirths thus constituting a significant drawback to the achievement of global health goals [4].

Detecting foetal abnormality early in pregnancy encourages intrauterine correction of certain foetal congenital defects, enables the family to appropriately manage the pregnancy if congenital abnormality is discovered as well as prepare for a high-risk delivery and arrangement for a specialised postnatal medical care and support if required [1]. Provision of PGS is one strategy to decrease infant morbidity and mortality associated with congenital abnormality [5].

Prenatal Genetic Screening is not a new concept but has been primarily targeted at pregnant women who are older than 35 years. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology

[5] has recommended that all pregnant women should be offered PGS before 20 weeks gestation. As a result, the number of screening procedures offered during the first and second trimester of pregnancy has increased rapidly during the last few years. Prenatal genetic screening is offered to all patients early in pregnancy in developed countries allowing them to identify common aneuploidies and open neural defects, as well as other congenital malformations [6]. Prenatal genetic screening for foetal anomalies includes a combination of maternal serum biochemical markers in the second trimester that includes unconjugated estriol, human chorionic gonadotropin, alpha-fetoprotein, and inhibin a assesses for Trisomy 18, Trisomy 21, and neural tube defects [7]. Other non-invasive prenatal screening techniques include nuchal translucency, an ultrasound scan technique where the fluid volume at the back of the foetal neck is measured between 10-14 weeks gestation, foetal echocardiography, and magnetic resonance imaging among others. Non-Invasive Prenatal Diagnostic Test (NIPT) is another recent innovation, which utilises fragmented foetal DNA circulating in maternal blood, carries no risk and provides definitive chromosomal or molecular information about the foetus [8].

However, it has been reported that PGS is not routinely done and is virtually still at the primitive stage thus making it unavailable to many pregnant women in Nigeria [9] because of several issues associated with it. Some of the factors responsible for the non-availability are said to be the limitation of genetic testing, obtaining information when no intervention exists and the issue of undesired option of abortion due to the restrictive law of abortion in Nigeria [10]. Despite these drawbacks, the need for PGS cannot be overlooked, previous studies have shown that it encourages intrauterine correction of certain foetal congenital defect, enables the family to appropriately manage the pregnancy if congenital abnormality is discovered as well as prepare for a high-risk delivery and arrangement for a specialised postnatal medical care and support if required [1, 5,11]. It also provides reassurance to the family concerning the health of the baby if the test result is favourable. In view of these there is need to assess factors associated with prenatal genetic testing uptake if PGS is to be made available and as part of routine testing to pregnant women in Nigeria.

An important concept required for making informed decisions about the uptake of any prenatal test that can be offered to pregnant women is their knowledge and perception. The concept of informed choice in PGS is based on both relevant knowledge and personal belief and values, which will reflect in the behaviour towards PGS. The amount of information provided on PGS will provide the basis for autonomy, which determines choice [12]. The extent to which PGS have been taken up by pregnant women varies, studies have suggested that majority of women declined PGS due to lack of knowledge and understanding [13,14,7]. The lack of knowledge and understanding of PGS can complicate the decision-making and increase anxiety for families who lack information resources [12]. Religious beliefs surrounding reproductive choice and pregnancy termination can also prevent women from choosing to accept PGS [15,16].

There is paucity of studies on PGS in Nigeria and policymakers are not prioritising PGS as an essential element to the achievement of sustainable health goals. Thus, this study aimed to determine the impact of educational intervention on knowledge, perceptions and readiness to uptake prenatal genetic screening among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Idi Araba, and Lagos State.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study is a pilot study conducted prior to a main study proposed to be conducted in selected Teaching Hospitals in Southwestern Nigeria.

Study Design

Quasi-experimental design.

Study Setting

This pilot study was conducted in the antenatal clinic of Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Idi Araba (LUTH). LUTH is a tertiary institution in Lagos state, Southwestern region of Nigeria, which serves as a referral centre for the neighbouring primary, secondary and private health facilities. The Obstetrics and Gynaecology department provides antenatal care and delivery management for booked patients. It also accepts unbooked patients and treats obstetric and gynaecological emergencies admitted through accidents and emergencies. The antenatal clinics are run four days in a week with an average of 100 pregnant women per week.

Study Population

All antenatal clinic attendees aged 18 years and above whose pregnancy were below 34 weeks of gestation at the antenatal clinic of LUTH. This is to ensure that the women will be available at the time of intervention.

Sample Size Calculation

As a pilot study, 10% of the total population of the main study (260) was used (n = 26). However, a total of 35 pregnant women participated in the study because of attrition.

Sampling Technique

Participants were recruited into the study using a simple random sampling method by asking eligible pregnant women to pick a random paper that has Yes/No written on it. Those who picked a yes and gave consent were recruited to participate in the study.

Research Instrument

Instruments utilised for this study was adapted questionnaire from previous study [2] and Educational Intervention package developed by the researcher. The structured questionnaire consists of four different sections. Section A contains 11 questions that elicit information on sociodemographic characteristics of participants and reproductive history, Section B contains 40 open and close ended questions that assessed respondents’ knowledge of genetic disease and the various PGS and diagnostic test as well as their source of knowledge, each correct answer was scored 1 while incorrect answer was scored as 0, Pass mark was set at 75th percentile, with score above 75% and above regarded as good knowledge; 50 to 75% as moderate knowledge while score below 50% were regarded as poor Section C contain 20 questions which assessed the perception of the respondents towards PGS, the need for PGS and their personal disposition towards PGS on a five-point Likert scale (5. Strongly Agree, 4. Agree, 3. Undecided, 2. Disagree and 1. Strongly Disagree) with greater scores indicating more positive perception towards PGS while Section D collected information on readiness of participants to be screened on a 5-point Likert scale. The face and content validity and the reliability of the instrument was established by test-retest prior to the administration of the questionnaire. The reliability of the instrument was measured using Cronbach alpha correlation and was found to be 0.79.

The Intervention Tool

The researcher developed the intervention tool (Midwife-led educational intervention) and it contains general information about common congenital abnormality and causes, prenatal genetic screening, the various methods of screening as well as the benefit of up taking the screening during pregnancy.

Procedure for Data Collection

Data was collected in three phases viz the pre-intervention phase, intervention phase and the post intervention phase. The first phase includes collection of baseline data using a self- administered questionnaire. The intervention was a training that was conducted among the pregnant women on a predetermined date and time. The respondents were exposed to 2 sessions of education on prenatal genetic screening, each session lasting 45 minutes in addition to standard care they normally receive on their antenatal day. The participants were educated on congenital malformation, prenatal genetic screening as well as the benefits of PGS. Each participant was also given a copy of the information booklet after the intervention. Immediate post intervention administration of the same questionnaire was done. Data collection took a period of two weeks.

Data Management and Analysis

Preliminary cleaning of the data was done for consistency. Data analysis was performed using the statistical package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25. Categorical variables like, ethnic group, religion, occupation and educational status were described in frequency and percentages. Continuous variables were summarised using mean, median and Standard Deviation. Relevant tables were used in presenting the results. Association or relationship between variables were tested using Mann Whitney U at 0.05 level of significance because the data was not normally distributed.

Ethical Consideration

Approval for the study was obtained from the ethical review committees of Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Idi Araba. Recruitment and participation were in accordance with ethical principles guiding research. Informed consent was obtained both in written and verbal form. The study was voluntary, harmless and confidentiality was assured and respected. The participants were adequately informed of the nature and purpose of the study. Due respect and courtesy were accorded to the participants.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. The mean age of the participants was 32.23 ± 4.99 years. More than three-quarters 27 (77.1%) were Christians while 8 (22.9%) were Muslims; Only 1 (2.9%) was single. More than half 20 (57.1%) had B.Sc. qualification Majority of respondents 31 (88.6%) were employed among which 17 (54.8%) were self- employed.

Table 1: Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

|

Socio-Demographic Characteristics |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Age Group |

||

|

21 - 30 |

14 |

40.0 |

|

31 - 40 |

19 |

54.3 |

|

41 years and above |

2 |

5.7 |

|

Mean Age ± SD |

32.2 ± 4.9 years |

|

|

Min. – Max. |

24 – 45 years |

|

|

Religion |

|

|

|

Christianity |

27 |

77.1 |

|

Islam |

8 |

22.9 |

|

Marital Status |

||

|

Single |

1 |

2.9 |

|

Married |

34 |

97.1 |

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

Yoruba |

15 |

42.9 |

|

Igbo |

12 |

34.3 |

|

Hausa |

2 |

5.7 |

|

Others |

6 |

17.1 |

|

Highest Educational Qualification |

||

|

None |

1 |

2.9 |

|

Secondary |

5 |

14.3 |

|

Diploma |

2 |

5.7 |

|

B.Sc. |

20 |

57.1 |

|

Others |

7 |

20.0 |

|

Employment Status |

||

|

Employed |

31 |

88.6 |

|

Unemployed |

4 |

11.4 |

|

Occupation (n = 31) |

||

|

Self Employed |

17 |

54.8 |

|

Employed by Private Organisation |

5 |

16.1 |

|

Employed by Government |

3 |

9.7 |

|

Professional |

5 |

16.1 |

|

Non-Response |

1 |

3.2 |

Table 2 showed the childbearing history of the participants. Information in the table revealed that about two-fifth 16 (45.7%) of the participants were primigravida. The median week of the participants’ gestational age was 28 weeks with interquartile range 20 to 31 weeks. Only 2 (5.7%) reported ever having a child with congenital malformation/birth defect while none reported family member with history of congenital abnormality.

Table 2: Child Bearing History of the Participants

|

|

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Number of Pregnancies |

||

|

1st |

16 |

45.7 |

|

2nd |

12 |

34.3 |

|

3rd |

4 |

11.4 |

|

≥ 4th |

3 |

8.6 |

|

Gestational Age |

||

|

1st Trimester |

4 |

11.4 |

|

2nd Trimester |

10 |

28.6 |

|

3rd Trimester |

21 |

60.0 |

|

Median (IQR) |

28.00 (20.00 31.00) weeks |

|

|

Min. – Max. |

6 – 34 weeks |

|

|

Ever had a child with congenital malformation/birth defects? |

||

|

Yes |

2 |

5.7 |

|

No |

33 |

94.3 |

|

Family member with congenital abnormality/birth defect |

||

|

Yes |

0 |

0 |

|

No |

35 |

100.0 |

Knowledge of Prenatal Genetic Screening

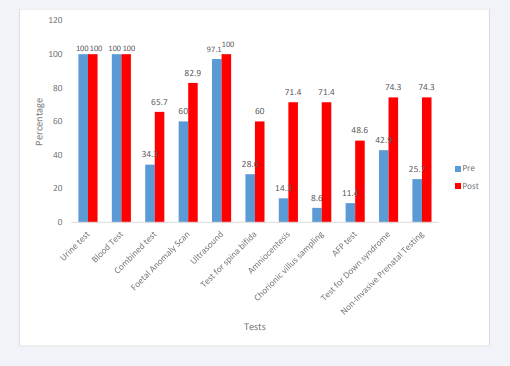

Figure 1 depicts the various tests that participants’ have heard of. Information in the chart showed that all the participants 35 (100.0%) have heard about urine and blood tests before and at post intervention.

Figure 1: Participant’s knowledge of methods of PGS.

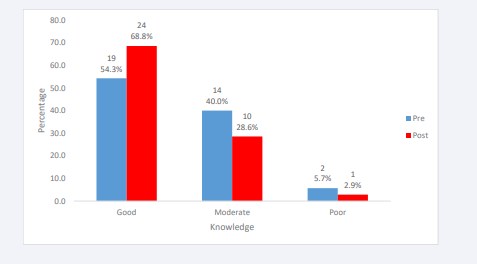

Majority of the participants have never heard about the different methods of PGS except for ultrasound (97.1%) and foetal anomaly scan (60.0%). Majority of the participants 26 (74.3%) believed that ultrasound can detect every form of birth defect while 20 (57.1 %) believed that a negative result from a chorionic villus sampling guarantees the absence of all birth defects and/or hereditary conditions. About 11% of the participants claimed they have heard about Alpa Feto Protein, which increased to 48.6% at post intervention. Further details of participant’s knowledge of PGS are shown in (Table 3) (Figure 2) revealed the general knowledge of the participants on congenital malformation and PGS. About 24 (68.8%) had good knowledge about genetic disease and prenatal genetic screening at post compared with 19 (54.3%) at pre-intervention.

Table 3: Participants’ Knowledge of Prenatal Genetic Screening Pre and Post Intervention

|

Knowledge |

Pre-Intervention |

Post Intervention |

||

|

Correct Response N (%) |

Wrong Response |

Correct Response N (%) |

Wrong Response N (%) |

|

|

Have you heard about prenatal genetic screening before? |

16 (45.7) |

19 (54.3) |

28 (80.0) |

7 (20.0) |

|

What do you understand by Prenatal genetic screening? |

12 (34.3) |

23 (65.7) |

24(68.6) |

11(31.4) |

|

What conditions do you think PGS can pick up in pregnancy |

9 (25.7) |

26 (74.3) |

19(54.3) |

16 (45.7) |

|

It is possible to find out if my unborn child has a genetic disease or birth defect |

30 (85.7) |

5 (14.3) |

35 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

An ultrasound can be used to detect every kind of birth defect |

9 (25.7) |

26 (74.3) |

8 (22.9) |

27 (77.1) |

|

The main use of an ultrasound is to check the age, sex and well-being of the baby |

29 (82.9) |

6 (17.1) |

30 (85.7) |

5 (14.3) |

|

First trimester screening involves ultrasound and a maternal blood test. |

31 (88.6) |

4 (11.4) |

34 (97.1) |

1 (2.9) |

|

If a first trimester screening test shows at increased risk, further tests can be done to clarify a diagnosis |

31 (88.6) |

4 (11.4) |

33 (94.3) |

2 (5.7) |

|

Tests can be done as early as 11-13 weeks or in the first 3 months to identify pregnancies at risk of Down syndrome |

27 (77.1) |

8 (22.9) |

33 (94.3) |

2 (5.7) |

|

Second trimester ultrasound scan can be done between 18 and 22 weeks of pregnancy |

34 (97.1) |

1 (2.9) |

34 (97.1) |

1 (2.9) |

|

Second trimester ultrasound scan at 22 weeks detects heart malformations |

30 (85.7) |

5 (14.3) |

34 (97.1) |

1 (2.9) |

|

Second trimester maternal serum screening detects only Down syndrome |

18 (51.4) |

17 (48.6) |

11 (31.4) |

24 (68.6) |

|

If second trimester maternal serum screening shows at increased risk, further tests can be done to clarify a diagnosis |

32 (91.4) |

3 (8.6) |

35 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

If a positive screening result is given, this means that the foetus definitely has Down syndrome or a neural tube defect |

11 (31.4) |

24 (68.6) |

7 (20.0) |

28 (80.0) |

|

Ultrasound scans can be done in the first, second and trimesters to detect possibilities of birth defects in the foetus. |

30 (85.7) |

5 (14.3) |

32 (91.4) |

3 (8.6) |

|

Amniocentesis is a test of the mother’s blood |

8 (22.9) |

27 (77.1) |

6 (17.1) |

29 (82.9) |

|

A negative result from a chorionic villus sampling guarantees the absence of all birth defects and/or hereditary conditions |

15 (42.9) |

20 (57.1) |

25 (71.4) |

10 (28.6) |

|

Both amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling provide certainty about the presence of Down’s syndrome in an unborn child |

24 (68.6) |

11 (31.4) |

34 (97.1) |

1 (2.9) |

|

There is a chance of miscarriage associated with chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis. |

20 (57.1) |

15 (42.9) |

28 (80.0) |

7 (20.0) |

|

Repeatedly performing a scan is dangerous for the unborn child |

22 (62.9) |

13 (37.1) |

22 (62.9) |

13 (37.1) |

Figure 2: Participants’ general knowledge of PGS and congenital malformation.

Participants Perception Towards Prenatal Genetic Screening

Figure 3 depicts the perception of the participants towards prenatal genetic screening at pre and post interventions. Information in the figure showed that only 11 (31.4%) had positive perception towards prenatal genetic screening even at post intervention compared with pre-intervention at 10 (28.6%), detailed information can be seen in (Table 4).

Figure 3: Perception of the Participants towards PGS.

Table 4: Participants’ perception of Prenatal Genetic Screening

|

Statement |

Pre-Intervention |

Post Intervention |

||||

|

D |

U |

A |

D |

U |

A |

|

|

Perceived Benefits |

||||||

|

Prenatal genetic screening tests are valuable for pregnant women and their foetuses |

0 (0.0) |

3 (8.6) |

32 (91.5) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (2.9) |

34(97.2) |

|

Prenatal genetic screening (first trimester screening, quad screening, NIPT, cell-free DNA) should be offered to all pregnant women |

0 (0.0) |

8 (22.9) |

27 (77.1) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

35 (100.0) |

|

Prenatal genetic screening should be an integral part of antenatal care services. |

0 (0.0) |

3 (8.6) |

32 (91.4) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

35 (100.0) |

|

Prenatal genetic screening will reduce my fear of having a child with congenital malformation. |

1(2.9) |

2 (5.7) |

32(91.4) |

0 (0.0) |

3 (8.6) |

32 (91.4) |

|

Prenatal genetic screening will help me to detect earlier if my child has any genetic/ congenital abnormality |

1 (2.9) |

3 (8.6) |

32 (88.6) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (2.9) |

34 (97.1) |

|

Prenatal genetic screening should be made voluntary for all pregnant women after necessary counselling |

2 (5.4) |

1 (2.9) |

32 (91.5) |

3(8.6) |

0 (0.0) |

32 (91.4) |

|

Prenatal genetic screening will help doctors find cure for genetic disease and birth defects in children. |

1 (2.9) |

6 (17.1) |

28 (80.0) |

1 (2.9) |

3 (8.6) |

32 (88.6) |

|

If all women perform prenatal genetic screening during pregnancy, the rate of genetic or congenital birth defects would decrease greatly |

2 (5.7) |

2 (5.7) |

31 (88.6) |

3 (8.6) |

0 (0.0) |

32 (91.4) |

|

If I underwent prenatal genetic screening, I will be satisfied with myself |

0 (0.0) |

11 (31.4) |

24 (68.6) |

1 (2.9) |

4 (11.4) |

30 (85.7) |

|

Prenatal genetic screening will help reduce my anxiety during my pregnancy. |

1 (2.9) |

4 (11.4) |

30 (85.8) |

3 (8.6) |

0 (0.0) |

32 (88.4) |

|

General perception |

||||||

|

Prenatal genetic screening test should be made free for all pregnant women |

1 (2.9) |

4 (11.4) |

30 (85.7) |

0 (0.0) |

2 (5.7) |

33 (94.2) |

|

Non-invasive prenatal testing should be made available for all pregnant women |

0 (0.0) |

5 (14.3) |

30(74.7) |

1 (2.9) |

4 (11.4) |

30 (85.7) |

|

Screening for foetal anomaly scan should be made compulsory for all pregnant women |

2 (5.7) |

6 (17.1) |

27 (77.2) |

1 (2.9) |

3 (8.6) |

31 (88.5) |

|

Perceived Barrier |

||||||

|

Participating in first trimester prenatal screening for any congenital malformation is, in my opinion a waste of resources |

24 (68.6) |

5 (14.3) |

6 (17.2) |

24 (68.6) |

2 (5.7) |

9(25.7) |

|

There is no reason for me to undergo prenatal genetic screening. |

24 (68.6) |

9 (25.7) |

2 (5.7) |

28(80.0) |

3 (8.6) |

4 (11.5) |

|

Prenatal genetic screening will make me worry about my baby unnecessarily |

17 (48.6) |

6 (17.1) |

12 (34.3) |

18(51.4) |

5 (14.3) |

12 (34.3) |

|

Prenatal genetic screening is too costly |

2 (5.7) |

18 (51.4) |

15 (42.9) |

4 (11.4) |

20 (57.1) |

11 (21.4) |

|

Prenatal genetic screening will exhaust me and my spouse physically, emotionally and psychologically |

16 (45.7) |

8 (22.9) |

11(31.4) |

17 (48.5) |

5 (14.3) |

13 (37.2) |

|

Going for prenatal genetic screening will not have any impact on my decision to continue with the pregnancy or not. |

10 (28.6) |

9 (25.7) |

16 (45.7) |

11 (31.4) |

8 (22.9) |

16(45.7) |

|

It is not advisable to perform any prenatal genetic screening test during pregnancy because something negative could be discovered |

24 (68.5) |

6 (17.1) |

5 (13.3) |

24 (68.6) |

1 (2.9) |

10 (28.6) |

Participants’ Readiness to Uptake Prenatal Genetic Screening

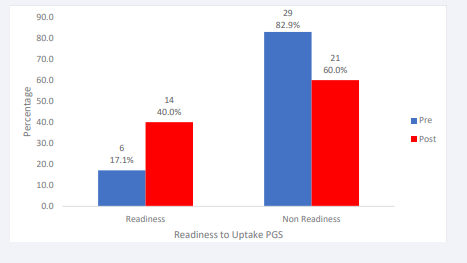

Generally, moreparticipantsstronglyagreed on theirreadiness to uptake prenatal genetic screening at post intervention. Also, at post intervention, more participants 24 (68.6%) strongly agreed that they will definitely go for prenatal genetic screening if available compared with 15 (42.9%) that strongly agreed at pre- intervention. About 42.9% of the participants also reported that they would still go for screening even if their husband disagrees with their decision to uptake PGS, which increase to 48.6% at post intervention. Further information can be seen as shown in (Table 5).

Table 5: Readiness to Uptake PGS

|

Statement |

SD |

D |

U |

A |

SA |

|

Pre-Intervention |

|||||

|

I will definitely go for prenatal genetic screening if available |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

4 (11.4) |

16 (45.7) |

15 (42.9) |

|

There is a high probability that I will uptake prenatal genetic screening in my next pregnancy |

0 (0.0) |

1 (2.9) |

9 (25.7) |

14 (40.0) |

11 (31.4) |

|

I will recommend Prenatal genetic screening to other pregnant women |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

5 (14.3) |

18 (51.4) |

12 (34.3) |

|

I will not go for any Prenatal Genetic screening if my husband says NO |

5 (14.3) |

15 (42.9) |

9 (25.7) |

2 (5.7) |

4 (11.4) |

|

I think prenatal genetic screening is an essential part of Antenatal care |

1 (2.9) |

0 (0.0) |

3 (8.6) |

13 (37.1) |

18 (51.4) |

|

Post Intervention |

|||||

|

I will definitely go for prenatal genetic screening if available |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (2.9) |

10 (28.6) |

24 (68.6) |

|

There is a high probability that I will uptake prenatal genetic screening in my next pregnancy |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

3 (8.6) |

9 (25.7) |

23 (65.7) |

|

I will recommend Prenatal genetic screening to other pregnant women |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

9 (25.7) |

26 (74.3) |

|

I will not go for any Prenatal Genetic screening if my husband says NO |

6 (17.1) |

17 (48.6) |

6 (17.1) |

2 (5.7) |

4 (11.4) |

|

I think prenatal genetic screening is an essential part of Antenatal care |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

10 28.6) |

25 71.4) |

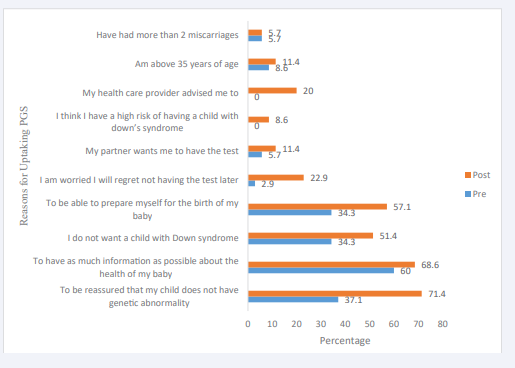

Figure 4 also depicts that more participants (40.0%) are ready to uptake at post intervention than at pre-intervention (17.1%), even though it is less than 50% of the total participants. Some of the reason for participant’s readiness to uptake PGS are depicted in (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Readiness to Uptake PGS among the Participants.

Figure 5: Reason for readiness to uptake

DISCUSSION

The study sought to determine the effect of educational intervention on the knowledge and readiness of pregnant women to uptake prenatal genetic screening. The knowledge of PGS among pregnant women is an important aspect of their readiness to uptake PGS which will eventually affect the incidence of congenital malformation with subsequent decrease in neonatal mortality. In addition, early diagnosis of a child with congenital malformation provides the parents with an opportunity to establish a care team and a care plan before the delivery and associated intervention options as well as the care of the mother during pregnancy and the newborn [11].

Knowledge of Prenatal Genetic Screening among Pregnant Women

About half of the participants were found to have good knowledge of PGS prior to intervention, this is slightly higher than previous studies that have shown low level of understanding of prenatal genetic screening among pregnant women [12,16,17]. Similarly, a qualitative study conducted by Page, et al. [7] revealed a limited understanding and knowledge of prenatal genetic screening among their respondents. This slight disparity may suggest that population receiving care from tertiary institution are better informed than those in primary secondary facilities. Awareness of the participants on prenatal genetic screening methods for congenital defect was very low. Majority of the participants have not heard of the different methods of PGS such as Alpha Foeto Proteins (AFP), Maternal Serum Screening (MSS), amniocentesis, chorionic villus samplings among others, the most known method was ultrasound. This could be attributed to the fact that ultrasound is the main method of prenatal genetic screening in the study centre and the fact that Ultrasound has many benefits with no known complications associated with it [17]. In addition, ultrasound is the cheapest form of PGS to assess foetal health. The result of this study also mirrors the findings from previous studies where participants find it challenging to identify majority of the methods of PGS [7,9]. Generally, more participants reported that they have heard about the listed tests after intervention compared with the percentage that heard about it before intervention.

Perception of Respondents’ Towards PGS

This study revealed a negative perception of participants towards prenatal genetic screening. This is contrary to reports of previous studies which showed good attitude scores of participants towards PGS [2,12]. El-Said, et al. [18] in their study also discovered that more than three quarter of the pregnant women in their study showed a positive attitude towards prenatal genetic screening and showed their willingness to uptake the screening if recommended by their consultant. The discordant in the result may be because this is a pilot study with fewer respondents and majority of the respondents were primigravida

Readiness to Uptake Prenatal Genetic Screening

Most of the participants have never gone for PGS before the study but some of them indicated their readiness to undergo the screening after the intervention. This is because PGS is usually not part of the topic for discussion during regular antenatal clinic, which can serve as barrier for uptake. Similar studies have shown participants’ willingness to undergo PGS following intervention [17,18]. Reasons given by majority of the participants for their readiness to uptake is that they want to be reassured that their babies do not have any abnormality, and that they will like to have as many information as possible about the health of their baby. In addition, the reason for readiness of participants for screening in this study may be attributed to the fact that majority of the participants were primigravida. First pregnancies may be confusing to most women; as a result, screening was accepted in order to feel reassured about foetal health. However, Chen, et al. [19] suggested that primigravida tends to assume that whatever service the health care system offer is well thought of and it is likely to be the best option for them [19].

Effect of Intervention on Knowledge and Readiness For Uptake

The educational intervention utilised in this study provide an immediate effect in improving the knowledge of the participants and their readiness to uptake PGS, even though the effect on their perception was minimal. The findings revealed that despite improvement in the knowledge of participants following intervention, the pregnant women’s perception towards PGS varies and are generally negative. The educational intervention was found to have no significant impact on the perception of the participants toward PGS. This is in contrast to a study conducted by Steven, et al. [11], which revealed an instant improvement in the attitude of the pregnant women towards PGS for sickle cell disease following a clinical vignette intervention. The result is in tandem with the result of the study by Peters, et al. [20] and Rabiee, et al. [21], which is also corroborated by a study conducted by Stortz, et al. [6] that revealed that video education on prenatal genetic testing improved patients’ knowledge on PGS. Yeniceri, et al. [22], in their study also discovered in their study that women had inadequate knowledge about PGS and revealed that provision of education in addition to a written information brochure of information increased their knowledge considerably. The result of this study is also supported by a study conducted by Smith, et al. [23], which showed an increase in pregnant women’s knowledge of different type of screening test after exposure to a decision aid tool on PGS for Down’s syndrome. This indicates that providing adequate information to pregnant women will promote awareness and knowledge of innovations in their care as well as foster making an informed decision regarding their health and the health of their unborn baby. Education has been found to be a cost effective and feasible means of promoting knowledge and engagement as well as potential uptake of health behaviour.

The study revealed a significant difference in the median knowledge score of the participants at pre and post intervention but no significant difference in the median perception score of the participants at pre and post intervention stage. In addition, the study revealed a significant difference in the proportion of participants who are ready to uptake PGS at pre and post intervention stage. This indicates that for a significant portion of pregnant women, provision of adequate information by their healthcare provider, as well as the professional recommendation of their physician, would be crucial to their choice about PGS. The discussion between the patient and healthcare provider surrounding PGS has the potential to significantly affect a woman’s views toward this type of screening. In view of the significance of the information that can be obtained through PGS and the possible difficult decisions that the screening could lead to, it is important that pregnant women make a thoughtful and informed decision, which requires provision of comprehensive information and discussion with the health care provider. Furthermore, the only sociodemographic variable that was found to have significant relationship between knowledge of PGS was age of the pregnant women. The older the pregnant women, the higher their likelihood of acceptance of PGS. This is similar to the results of previous studies [2,17] No association was found between sociodemographic variables and readiness to uptake.

Most of the participants agreed that PGS should be made available to all pregnant women during antenatal clinic therefore. Health professionals, in particular, obstetricians, midwives, genetic counsellors as well as primary care physicians can benefit from this study by educating clients and their families on the importance of prenatal genetic screening in order to facilitate decision-making. Community intervention such as educating the general populace, creating awareness in church, mosque and market place may also facilitate the readiness to uptake PGS. Early and appropriate information should be offered to all pregnant women in a group session, followed by individual session for those who are interested. To do this, there is need for continuing education for health care providers to ensure that the providers have sufficient knowledge about PGS so that patients can make informed decision whether to go for screening or not.

This study utilised an integrated model that integrates 2 validated theories viz Health belief Model and Theory of planned behaviour with five specific constructs such as knowledge, perceive barriers, perceived benefits, attitudes as well as intention which have been used to test participants perception and readiness to uptake PGS.

LIMITATION

Only 35 pregnant women participated because this is mainly a pilot study, despite the fact that the sample is small, we had sufficient power to detect minimal effects. Additionally, the study was unable to evaluate the actual uptake of PGS among the participants due to absence of facilities for PGS at the hospital.

CONCLUSION

Congenital malformation is one of the largest contributors to neonatal mortality. Prenatal genetic screening is one of the ways to reduce the incidence and subsequently neonatal mortality. Various methods of PGS are now recommended for all pregnant women in developed countries but in developing countries like Nigeria, its availability it is limited to routine ultrasonography. There is a clear need for prenatal genetic education for all pregnant women. This educational intervention was found to be acceptable and effective in promoting women’s knowledge and readiness to uptake PGS. Even though, this a pilot study it shows that increasing knowledge of PGS will facilitate uptake of PGS among pregnant women. Promoting uptake of PGS will reduce the burden of care and the psychological distress that usually result from having a baby with congenital abnormality, as well as reduce the prevalence of neonatal mortality thus ensuring the achievement of healthy goals. It is important that pregnant women be provided adequate information about PGS in order to facilitate informed decisions.

RECOMMENDATION

Nurses and medical practitioners as key players in promoting maternal and child health must take up the responsibility to constantly provide necessary information to pregnant woman at booking and during antenatal clinics. Health care workers should intensify efforts of highlighting the importance and benefits to the wellbeing of their babies thus reducing the burden of care resulting from having a baby with congenital abnormality. In addition, the policy makers in health ministries need to provide appropriate legislation and policy on prenatal genetic screening that will incorporate and expand it into the different level of care. Furthermore, there is a need to train the health care workers especially on maternal foetal medicine for doctors, genetic counselling education for nurses and in-country prenatal genetic screening to detect aneuploidies early.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank all the pregnant women that participated in the study. Special appreciation to all the nurses and midwives at LUTH for their support during the data collections.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organisation Factsheet 2022. Autism.

- Ogamba CF, Roberts AA, Babah OA, Ikwuegbuenyi CA, Ologunja OJ, Amodeni OK. Correlates of knowledge of genetic diseases and congenital anomalies among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in Lagos, South-West Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2021; 38: 310. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.38.310.26636. PMID: 34178228; PMCID: PMC8197039.

- Adekanbi AO, Olayemi OO, Fawole AO. The knowledge base and acceptability of prenatal diagnosis by pregnant women in Ibadan. Afr J Reprod Health. 2014; 18(1): 127-132. PMID: 24796177.

- De Silva J, Amarasena S, Jayaratne K, Perera B. Correlates of knowledge on birth defects and associated factors among antenatal mothers in Galle, Sri Lanka: a cross-sectional analytical study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019; 19(1): 35. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2163-9. PMID: 30654759; PMCID: PMC6337825.

- ACOG and SMFM. Ob-Gyns release revised recommendations on screening and testing for genetic disorders. Press Release 2016.

- Stortz SK, Mulligan S, Snipes M, Hippman C, Shridhar NN, Stoll K, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial on the Effect of Standardized Video Education on Prenatal Genetic Testing Choices: Uptake of Genetic Testing. Am J Perinatol. 2023; 40(3): 267-273. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1727229. Epub 2021 Apr 20. PMID: 33878774.

- Page RL, Murphey C, Aras Y, Chen LS, Loftin R. Pregnant Hispanic women’s views and knowledge of prenatal genetic testing. J Genet Couns. 2021; 30(3): 838-848. doi: 10.1002/jgc4.1383. Epub 2021 Jan 26. PMID: 33496987; PMCID: PMC8248231.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologist (2020). Prenatal genetic screening tests.

- Ogamba CF, Roberts AA, Balogun MR. Genetic diseases and prenatal genetic testing: knowledge gaps, determinants of uptake and termination of pregnancies among antenatal clinic attendees in Lagos, south west Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci research. 2018; 8: 143-150.

- Ajah LO, Nwali SA, Amah CC, Nwankwo TO, Lawani LO, Ozumba BC. Attitude of Reproductive Healthcare Providers to Prenatal Diagnosis in a Low Resource Nigerian Setting. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017; 11(2): QC04-QC07. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/22874.9424. Epub 2017 Feb 1. PMID: 28384937; PMCID: PMC5376790.

- Steven M, Akyüz A, Eroglu K, Daack-Hirsch S, Skirton H. Women’s knowledge and utilization of prenatal screening tests: A Turkish study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2016; 26.

- Pop-Tudose ME, Popescu-Spineni D, Armean P, Pop IV. Attitude,knowledge and informed choice towards prenatal screening for Down Syndrome: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018; 18(1): 439. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2077-6. PMID: 30419853; PMCID: PMC6233289.

- Chetty S, Garabedian MJ, Norton ME. Uptake of noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) in women following positive aneuploidy screening. Prenat Diagn. 2013; 33(6): 542-546. doi: 10.1002/pd.4125. PMID:23592525.

- Farrell R, Hawkins A, Barragan D, Hudgins L, Taylor J. Knowledge, understanding, and uptake of noninvasive prenatal testing among Latina women. Prenat Diagn. 2015; 35(8): 748-753. doi: 10.1002/pd.4599. Epub 2015 May 21. PMID: 25846645.

- Floyd E, Allyse MA, Michie M. Spanish- and English-Speaking Pregnant Women’s Views on cfDNA and Other Prenatal Screening: Practical and Ethical Reflections. J Genet Couns. 2016; 25(5): 965-977. doi: 10.1007/s10897-015-9928-3. Epub 2016 Jan 7. PMID: 26739840; PMCID: PMC4936962.

- Abousleiman C, Lismonde A, Jani JC. Concerns following rapid implementation of first-line screening for aneuploidy by cell-free DNA analysis in the Belgian healthcare system. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019; 53(6): 847-848. doi: 10.1002/uog.20280. PMID:30937993.

- Winters P, Curnow KJ, Benachi A, Gil MM, Santacruz B, Nishiyama M, Hasegawa F, Sago H. Multisite assessment of the impact of a prenatal testing educational App on patient knowledge and preparedness for prenatal testing decision-making. J Community Genet. 2022; 13(4): 435-444. doi: 10.1007/s12687-022-00596-x. Epub 2022 Jun 10. PMID: 35680723; PMCID: PMC9314500.

- El-Said R, El-Weshahi H T, Ashry M H. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of women in the reproductive age on prenatal screening for congenital malformations, Alexandria-Egypt. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 6: 1707-1712.

- Chen A, Tenhunen H, Torkki P, Peltokorpi A, Heinonen S, Lillrank P, et al. Facilitating autonomous, confident and satisfying choices: a mixed-method study of women’s choice-making in prenatal screening for common aneuploidies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018; 18(1):119. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1752-y. PMID: 29720125; PMCID: PMC5930782.

- Peters IA, Posthumus AG, Reijerink-Verheij JC, Van Agt HM, Knapen MF, Denkta? S. Effect of culturally competent educational films about prenatal screening on informed decision making of pregnant women in the Netherlands. Patient Educ Couns. 2017; 100(4): 776-782. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.11.007. Epub 2016 Nov 15. PMID: 27887753.

- Rabiee M, Jouhari Z, Pirasteh A. Knowledge of Prenatal Screening, Down Syndrome, Amniocentesis, and Related Factors among Iranian Pregnant Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2019; 7(2): 150-160. doi: 10.30476/ IJCBNM.2019.44886. PMID: 31041325; PMCID: PMC6456766.

- Yeniceri EN, Kasap B, Akbaba E, Akin MN, Sariyildiz B, Kucuk M, et al. Knowledge and attitude changes of pregnant women regarding prenatal screening and diagnostic tests after counselling. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 44(1): 48-55. PMID: 29714865.

- Smith SK, Cai A, Wong M, Sousa MS, Peate M, Welsh A, et al. Improving women’s knowledge about prenatal screening in the era of non-invasive prenatal testing for Down syndrome - development and acceptability of a low literacy decision aid. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018; 18(1): 499. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2135-0. PMID: 30558569; PMCID: PMC6296052.