Case Report with Pilomatrixoma with the appearance of Lymphadenopathy

- 1. Department of Child Hematology Oncology, University of Firat, Turkey

- 2. Departments of Pediatrics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA

- 3. Department of Radiology, University of Firat, Turkey

- 4. Department of Pathology, University of Firat, Turkey

Abstract

Background: Pilomatrixoma (benign calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe) is an uncommon benign tumor. It is frequently misdiagnosed as epidermoid or dermoid cyst. It has certain characteristic clinical and histopathologic features, but since it is not commonly suspected preoperatively, certain distinctive clinical features of tumor may suggest clinical diagnosis followed by histopathologic confirmation. We presented a female patient with pilomatrixoma who was treated many times with the preliminary diagnosis of lymphadenopathy.

Case presentation: We presented a case of a 15-year-old female found to have a large left cervical mass (6 cm×2.5 cm) and regional lymphadenopathy (<0.5 cm). The patient had a painless, slowly growing lesion over the left cervical region of 4 months duration. Examination showed a localized, subcutaneous, well-circumscribed, non-tender, pinkish-reddish mass with yellowish peripheral discoloration. The mass was firm-to-hard and adherent to overlying intact skin with gritty surface with telangiectatic vessels on palpation. Other physical examination findings and laboratory examinations were normal. MRI revealed a heterogeneously hyperechoic superficial oval formation with hypoechoic halo and calcifications. The mass was biopsied and proven to be a pilomatrixoma.

Conclusion: More than 70% of pilomatrixoma originate in the head and neck. The main pathological conditions of the neck in pediatric age are thyroid dysgenesis, thyroiditis, thyroid nodules, lymphadenopathies, cystic lesions, hemangiomas, vascular malformation, cervical thymus, fibromatosis colli and pilomatrixoma. Pilomatrixoma may rarely undergo malignant transformation into pilomatrix carcinoma. Unless the lesion is symptomatic, no treatment is require

CITATION

AKARSU S, YILDIRIM M, POYRAZ AK, ÖZERCAN IH (2025) Case Report with Pilomatrixoma with the appearance of Lymphadenopathy. Pediatr Child Health 15(1): 1345.

kEYWORDS

. Neck structures

• Paediatric age

• Pilomatrixoma

ABBREVIATIONS

MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging, CTNNB1: beta-cateningene

BACKGROUND

Cervical lymphadenopathy affects as many as 90% of children aged 4 to 8 years. The most common cause of cervical lymphadenopathy in the pediatric population is reactivity to known and unknown viral agents. The second most common cause includes bacterial infections ranging from aerobic to anaerobic to mycobacterial infections. Malignancies are the most concerning cause of cervical lymphadenopathy [1]. Among the diferent regions of the neck, normal cervical lymph nodes are commonly found in submandibular (19-23%), parotid (15-16%) and upper cervical (18–19%) regions, as well as the posterior triangle (35-37%) [2].

Pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe) is an uncommon benign tumor of the subcutaneous tissue originating from the hair follicle matrix cells. It commonly occurs in the pediatric patient on the hair-bearing areas of the head and neck but can also involve the extremities and trunk. On the head, the preauricular region is most commonly involved. The tumors only occur in hair-bearing areas. It was first described in 1880 by Malherbe and Chenantais. Over 70% of the tumors arise from the head and neck. Subsequently numerous ultrastructural and electron microscopic studies provided strong evidence of its origin from the matrix cells and the term pilomatrixoma was then coined by Forbis and Helwig keeping the histogenesis into consideration. These tumor cells can differentiate into hair matrix, hair cortex, follicular infundibulum, outer root sheath, and hair bulge. Case studies report the tumor occurring in other areas of the body including the periocular and on the scrotum and vulva [2-6].

We present a 15-year-old girl who was diagnosed with pilomatrixoma in the biopsy taken from a large mass in the left cervical region.

CASE PRESENTATION

We presented a case of a 15-year-old female found to have a large left cervical mass (6×2.5 cm) and regional lymphadenopathy (<0.5 cm) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A female case with a left pinkish-reddish anterior cervical mass (6×2.5 cm).

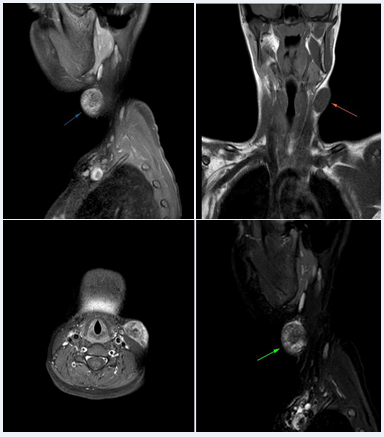

The patient had a painless, slowly growing lesion over the left cervical region of 4 months duration. Examination showed a localized, subcutaneous, well-circumscribed, non-tender, pinkish-reddish mass with yellowish peripheral discoloration. The mass was firm-to- hard and adherent to overlying skin with a gritty surface on palpation. Other physical examination findings and laboratory examinations were normal. MRI revealed a heterogeneously hyperechoic superficial oval formation with hypoechoic halo and calcifications (Figure 2).

Figure 2: On MRI, as a superficial oval formation, heterogeneously hyperechoic, hypoechoic halo and calcifications.

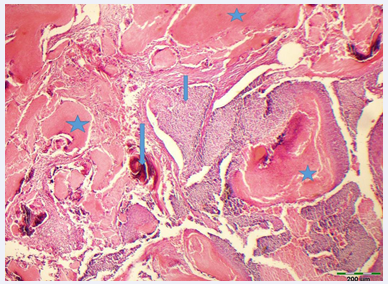

The mass was biopsied and proven to be a pilomatrixoma. The fibrous capsule surrounding the tumor was well-circumscribed and had firm to gritty in consistency (4×2x2 cm). Microscopic examination showed numerous lobules with basophilic cells in the periphery and of ghost-like squamous cells toward the center with a few anucleated cells. The fibrous capsule surrounding the tumor was well-circumscribed and had firm to gritty in consistency. Dermal cells extended into the subcutaneous tissue. There were islands of epithelial cells containing basaloid matrix cells, shadow, ghost (acellular eosinophilic material), or nucleated cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, and calcifications. These islands were surrounded by foreign body giant cells with a few lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates. Various stages of maturation of the basaloid cells into shadow cells were seen. There were numerous foci of calcification more so in the necrotic areas and in the periphery of cellular islands. Dense layers of eosinophilic keratinous material (foreign body giant cell reaction) were seen in necrotic areas (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Histological appearance of pilomatrixoma. Basaloid cells (short arrow), calcification (long arrow) and Ghost cell clusters (star). (Hematoxylin-Eosinx100).

DISCUSSION

Pilomatrixoma is benign tumor of the hair follicle matrix. The incidence of pilomatrixoma is reported to be between 0.001% and 0.0031% of all dermatopathology specimens and 20% of all pilar lesions. Another report listed the incidence at 0.18%. The cause of pilomatrixoma is uncertain. A familial component is seen in some cases as there is a genetic component to these lesions. A small percentage (3.9%) of cases are caused by an external insult such as trauma, insect bites, or surgery. Clinical features should arise clinical suspicion and they include onset in childhood or early adulthood, average size of 10 mm or less, consistency ranging from firm to cystic, moderate pattern of growth, pink to purple hue with subepithelial yellowish tinge, and intact overlying skin with telangiectatic vessels. Diagnosis is clinical or histological. The correct diagnosis was seen in only 12.5% to 55.5% of cases. There is low diagnostic accuracy because providers are unaware of the tumor and because pilomatrixoma mimics other lesions. Ultrasound can help correctly diagnose lesions preoperatively in 76% of cases compared to 33% when the diagnosis was made clinically. On a scan, it appears as a superfcial oval formation, heterogeneously hyperechoic with a hypoechoic halo and calcifcations [2,4,6].

Pilomatrixomas usually occur as solitary lesions, but multiple lesions can occur, often seen in syndromes such as myotonic dystrophy, Familial adenomatous polyposis, Gardner syndrome, Turner syndrome, xeroderma pigmentosum, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, Sotos syndrome, and basal cell nevus syndrome [4].

The exact cause of pilomatrixoma is not known. These tumors have been found to be possibly related to mutations in exon 3 of the beta-catenin gene (CTNNB1). B-catenin is a component of the cadherin protein, and it plays a role in hair follicle differentiation. High expression of B-catenin leads to activation of the Wnt signaling pathway, and this is seen in the matrix cells that are proliferating. B-catenin, during development, controls the adhesion between epithelial cells. Both benign and malignant lesions showed increased expression of beta-catenin, suggesting malignancy arises from a precursor benign lesion. Beta-catenin mutations may result in pilomatrixoma development and malignant transformation with additional mutations over time [3,4].

The mean age of onset is 4.5 years, and 90% of patients are younger than ten years old. There is a slight female predilection, and it occurs more commonly in whites. In the periocular area, it usually arises from the lids and eyebrows. It may show rapid progression, especially after trauma. There can be a blue or red color to the overlying skin, which can occasionally ulcerate. It is usually not associated with other signs or symptoms. But can report some pain or itching. The tent sign, a flattening of a part of the lesion with angulation resembling a tent, may be seen when the skin is stretched. Pigmented pilomatrixoma contains melanin or melanocytes, and it is thought to be rare [2,4,6].

Pilomatrixoma has been reported not only as a benign lesion, or as a low-grade malignant lesion with a tendency to recur locally, but also as a highly malignant tumour. The earliest known description of the malignant counterpart was by Gromiko in 1927. In a review of 125 registered cases of pilomatrix carcinoma revealed that 10 of those developed from histologically confirmed benign pilomatrixoma. Similar activating mutations of the Wnt signaling pathway have been found in both benign and malignant pilomatrixomas suggesting the possibility of malignant transformation. Pilomatrix carcinoma is a rare aggressive tumor with a high rate of local recurrence after surgical excision.

Diagnosis is made by histopathology and when discovered, wide local excision has been shown to have the best results. It is unknown if these tumors arise de novo or arise through malignant transformation of a benign pilomatrixoma. There are similarities between the benign lesion and its malignant counterpart in terms of activating mutations in signaling pathways. Overexpression of BCL2 proto-oncogene also has been seen in immunohistochemical studies [3,4].

Diagnosis is clinical or histological. The correct diagnosis was seen in only 12.5% to 55.5% of cases. There is low diagnostic accuracy because providers are unaware of the tumor and because pilomatrixoma mimics other lesions. Imaging is generally not performed. If imaging is necessary, x-ray, computed tomography, or ultrasound can be done to rule out vascular or lymphatic malignancies. Ultrasonography is crucial for the detection of neck pathologies in children. Ultrasound can help correctly diagnose lesions preoperatively in 76% of cases compared to 33% when the diagnosis was made clinically. Ultrasound can be used to distinguish heterogeneous echotexture, calcifications, hypoechoic rim, and posterior shadowing. On a scan, it appears as a superfcial oval formation, heterogeneously hyperechoic with a hypoechoic halo and calcifcations [2,4].

Clinical differential diagnosis includes epidermoid cysts, dermoid cyst, sebaceous adenoma or carcinoma, juvenile xanthogranuloma, capillary hemangioma, chalazion, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Although they grow slowly, they occasionally demonstrate rapid growth and may resemble keratoacanthoma. They can rarely undergo malignant transformation into pilomatrix carcinoma. Histopathologic differential diagnosis include basal or squamous cell epitheliomas as well as a variety of skin and subcutaneous cysts. The differential diagnosis includes sebaceous and epidermoid cysts, epitheliomas, neurofibromas, foreign body reactions, calcified cysts or hematomas, chondromas, fibroxanthomas, osteoma cutis, and giant cell tumor [2,4,6,7]. Kimura’s disease is is characterized by head and neck subcutaneous nodules along with lymphadenopathy, which is usually solitary but can be generalized. It is diagnosed histopathologically [8].

Pilomatrixoma can be appropriately treated while avoiding unnecessary diagnostic tests. Complete surgical excision with clear margins is almost always curative [9].

Pilomatrix carcinoma shows basaloid cells, atypia, and a high mitotic rate on histology. Ghost cells are present. Not many calcifications are seen. The histological features between pilomatrixoma and pilomatrix carcinoma are similar and can be difficult to differentiate [4].

a proliferation of pleomorphic hyperchromatic basaloid cells with areas of squamous metaplasia and exhibits numerous mitoses and prominent nucleoli. Pilomatrix carcinomas also have an infiltrative growth pattern and can have necrosis and lymphovascular invasion [2]. Pilomatrix carcinoma is a rare malignant and locally aggressive hair follicle tumor with a high propensity for recurrence after excision. It is important to perform wide local excision to avoid an incomplete resection and higher recurrence rates. A well-defined gold standard for surgical management has not been established. Wide local excision with safe margins is recommended along with regional lymph node dissection when metastasis is suspected. Most authors recommend wide local excision with safe margins of 0.5 cm–1 cm as opposed to simple excision, as an incomplete resection results in high recurrence rates. In simple excision, the recurrence rate increases to 50-60% [7]. A recurrence rate of 83% in tumors that were simply excised versus a recurrence rate of 23% in tumors that were extensively excised was reported. Metastasis occurred in 13% of the cases. Regional lymph nodes, lungs, bone, other internal organs, and brain are the most common sites of metastasis. In most cases, metastatic disease is noted at or after local recurrence. In a few cases, metastatic disease was detected at diagnosis or without clinical recurrence. Lymph node metastases should be treated by regional lymph node dissection combined with wide local excision of the primary lesion. The role of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy in treatment has yet to be fully defined and remains unclear. Neither treatment modality has shown a significant difference in modifying the disease course. Adjuvant radiation therapy is recommended for locoregional, metastatic, and recurrent disease, or if there are questions concerning clear margins. Currently, no chemotherapy regimen has been shown to be effective in local control or in preventing metastatic spread [3].

CONCLUSION

Although pilomatrixoma is an uncommon benign tumor and frequently misdiagnosed as epidermoid or dermoid cyst. ?t has some distinctive clinical features that suggest the correct diagnosis. Most healthcare professionals usually will not encounter this lesion but they need to know when to refer the patient to the dermatologist. Unless the lesion is symptomatic, no treatment is required. All malignant lesions require excision.

CONCLUSION

Although pilomatrixoma is an uncommon benign tumor and frequently misdiagnosed as epidermoid or dermoid cyst. ?t has some distinctive clinical features that suggest the correct diagnosis. Most healthcare professionals usually will not encounter this lesion but they need to know when to refer the patient to the dermatologist. Unless the lesion is symptomatic, no treatment is required. All malignant lesions require excision.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SA was a major contributor in writing the case report. AKP provided interpretation of the imaging. IHO performed the pathologic examination of the mass, MY revised the case report. All authors read and approved the case report.

DECLARATIONS

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given her consent for her images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understand that her name and initial will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardian for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

REFERENCES

- Weinstock MS, Patel NA, Smith LP. Pediatric Cervical Lymphadenopathy. Pediatr Rev. 2018; 39: 433-443.

- Caprio MG, Di Serafino M, Pontillo G, Vezzali N, Rossi E, Esposito F, et al. Paediatric neck ultrasonography: a pictorial essay. J Ultrasound. 2019; 22: 215-226.

- Martin S, DeJesus J, Jacob A, Qvavadze T, Guerrieri C, Hudacko R, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma of the right postauricular region: A case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019; 65: 284-287.

- Le C, Bedocs PM.Calcifying Epithelioma of Malherbe. 2023 Jun 12. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2024.

- Iqbal B, Putenparampil RA, Kambale T, Dharwadkar A, ViswanathanV. Calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe - a rare localization. Pol J Pathol. 2023; 74: 286-288.

- Singh M, Sharma M, Kaur M, Gupta P. Calcifying Epithelioma of Malherbe of the Eyebrow. Int J Trichology. 2020; 12: 41-42.

- Ali MJ, Honavar SG, Naik MN, Vemuganti GK. Malherbe’s Calcifying Epithelioma (Pilomatrixoma): An Uncommon Periocular Tumor. Int J Trichol. 2011; 3: 31-33.

- Anbessie ZM. Kimura’s disease: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2024; 18: 44.

- Jones CD, Ho W, Robertson BF, Gunn E, Morley S. Pilomatrixoma: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018; 40: 631-641.