Anemia Prevalence and Associated Factors among Pregnant Women in Mbujimayi, a Highly Endemic Malaria Region from the Democratic Republic of Congo

- 1. Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics, University of Kisangani, Democratic Republic of the Congo

- 2. Department of Public Health, University of Mbujimayi, Democratic Republic of the Congo

- 3. Research Center for the Infectious Diseases study, Doctoral School of Medicine, Osaka Metropolitan University, Japan

- 4. Department of Internal Medicine, University of Mbujimayi, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Citation

Jean Paul CK, Nadine KK, Arsène TB, Nestor KT, Evariste TK, et al. (2025) Anemia Prevalence and Associated Factors among Pregnant Women in Mbujimayi, a Highly Endemic Malaria Region from the Democratic Republic of Congo. Ann Pregnancy Care 7(1): 1016

INTRODUCTION

Anemia is a public health problem, predominantly affecting children and women of childbearing age. Defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a hemoglobin level below 11 g/dL, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines it as a hemoglobin level below 11 g/dL in the first and third trimesters, and below 10.5 g/ dL in the second trimester of pregnancy [1,2]. The global prevalence of anemia is 42% in pregnant women, and it is responsible for 20% of maternal deaths worldwide [3,4]. Its consequences also include an increased risk of neonatal mortality, preterm delivery and low birth weight [4]. African countries where malaria is endemic are the most affected by maternal anemia, with up to 57% of pregnant women in some regions [2,5-7]. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where malaria is hyper-endemic, the prevalence of maternal anemia can still be very high, reaching 76% in Kisangani, according to a study by Likilo et al. [8]. Among the main associated factors are parity, antenatal clinics (ANC), level of education and iron-folate supplementation [2,6,7]. Although the causes of maternal anemia are multiple, including nutritional deficiencies (vitamin B12, folic acid and iron deficiencies), chronic pathologies and intestinal parasitosis, malaria occupies a central position in endemic countries [2].

In areas with stable malaria transmission, maternal anaemia and placental malaria are major complications of malaria infection in pregnant women [9,10]. Plasmodium falciparum, the main species involved in malaria infections in Africa, can accumulate in the placenta and cause anaemia, even in the absence of parasites in the maternal peripheral blood. Every year, around 400,000 cases of severe maternal anaemia are attributed to malaria in sub Saharan Africa, with maternal mortality of almost 10,000 cases per year [11,12]. A study conducted in Republic of Congo by Massamba revealed that microscopic and submicroscopic malaria were twice as frequent in anemic parturients [13].

In view of these risks, the WHO recommends several strategies to prevent malaria during pregnancy, including the use of long-acting insecticide-treated mosquito nets (LLINs), intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTg-SP) and effective management of malaria and anemia [14]. However, coverage of these interventions remains insufficient in the DRC, particularly in the province of Kasaï-Oriental, where coverage of three-dose IPT-SP was only 16% according to the 2023-2024 Demographic and Health Survey. And yet, this province is one of the regions with the highest burden of malaria-related morbidity in the country [15].

In addition, the emergence and expansion of P. falciparum resistance to antimalarial drugs and mosquito resistance to insecticides threaten the effectiveness of the strategies advocated [16,17]. Recent studies have thus reported contrasting results on the effectiveness of IPT SP, imposing the need for ongoing evaluation of control strategies across the country. Labama et al. found an association between malaria and maternal anaemia at delivery, but no significant reduction in risk with IPT-SP in Kisangani [18]. Similarly, Kayiba et al., found that IPT-SP was not associated with a reduction in maternal malaria, although it did demonstrate a protective effect against maternal anaemia and preterm delivery in Kinshasa [19]. Against this backdrop, we undertook this study to estimate the prevalence of maternal anemia and identify associated factors in parturients in Mbujimayi, a highly malaria endemic area in central DRC. A better understanding of these determinants will enable us to adapt prevention strategies and improve care for pregnant women exposed to this risk.

METHODS

Setting, type and period of study

The study was carried out in Mbujimayi, capital of Kasaï-Oriental province in central DRC, in 4 health zones within the maternity wards of four hospitals, namely Bonzola, Christ-Roi, Sudmeco and La Grâce Divine. These sites had been selected because of their high attendance rates (an average of 40 deliveries per month), according to the National Health Information System (SNIS) report for 2022. The study was cross-sectional and analytical in nature, and took place over a seven-month period from August 15, 2023 to March 14, 2024. This duration includes site preparation, investigator training, data collection and analysis of biological samples.

Study population and minimum sample size

The study targeted all parturients presenting successively for delivery at the selected maternity hospitals during the study period. They were invited to participate in the survey, on the basis of defined selection criteria. The minimum sample size was calculated using the Schwartz formula, based on a 13.6% prevalence of placental malaria as a carrier of anemia, observed in Kwilu province [20]. Assuming a precision of 5%, the minimum number required was 180 parturients. A 10% increase was applied to account for non-response, bringing the final number to 199. All parturients admitted to the targeted maternity units were eligible for the study, regardless of gestational age, provided they had given informed consent. However, those for whom the essential study data were inaccessible,for whatever reason (e.g. advanced labor on admission, insufficient blood sample due to technical shortcomings or incomplete clinical assessment), were excluded from the analysis.

DATA COLLECTION

Data collection was carried out by a multidisciplinary team of 12 midwives or birthing nurses (three per targeted maternity hospital), two laboratory technicians, four medical student finalists in charge of logistics, a supervising physician and a principal investigator. These staff were qualified to carry out activities relating to delivery room management, and had received prior training in data collection for this survey.

On admission to the maternity unit, parturients were informed of the study objectives and invited to participate. After verification of eligibility criteria, they signed the informed consent form before undergoing a clinical examination. Data were then collected using a collection sheet, combining several methods: interviews, analysis of medical records, clinical and obstetrical examination, and biological analyses. Firstly, interviews were conducted using a structured questionnaire, translated into Tshiluba (the local language), and administered to parturients to gather socio-demographic, clinical and obstetrical information. This information was then supplemented by analysis of individual medical records, including prenatal consultation records. Finally, two milliliters of maternal venous blood were collected on EDTA for various biological analyses, including a Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT), microscopic examination of a thick drop and a thin blood smear, and hemoglobin determination.

At the same time, all data was entered daily and compiled on electronic sheets designed with the KoboToolbox application (https://kf.kobotoolbox.org/), installed on cell phones. Ongoing supervision was set up to identify and correct any data entry errors or inconsistencies. Finally, at the end of the survey, the database was exported in Excel format(Microsoft Office 2010, USA), checked, corrected and consolidated into a single, definitive database.

Laboratory analysis

Duly labelled EDTA blood tubes were sent daily, within 4 hours of collection, to the analysis laboratory at Valentin Disashi Hospital for screening for maternal anemia, as well as testing for Plasmodium spp. by RDT and thick drop by two experienced laboratory technicians. As soon as the tube was received, drops of blood were pipetted and deposited successively on the RDT device, on a slide for thick drop and thin smear, and on a microcuvette for haemoglobin measurement.

The SD Bioline© RDT (Standard Diagnostics Bioline©, South Korea) used is an immunochromatographic test that detects the histidine-rich protein 2 (HRP-2) of P. falciparum. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, a drop of blood (50 µL) was placed in the reaction well of the test device, then dilution buffer was added. The sample migrated along the test strip and the results were interpreted after 15 minutes. The appearance of a band in the ‘control zone’ validated the test, while an additional band in the ‘test zone’ indicated a positive result for P. falciparum. A HemoCue® Hb 301 automatic hematology analyzer (HemoCue® AB, Ängelholm, Sweden 2020) was used to measure hemoglobin levels. The principle of this measurement is based on spectrophotometric determination (at 570 nm and 880 nm) of the absorbance of turbidity resulting from the transformation of hemoglobin into azidemethhemoglobin after lysis of red blood cells. To do this, a microcuvette loaded with a drop of blood was inserted into the device; the system analyzed the sample photometrically, then displayed the results almost instantaneously on the screen, indicating the hemoglobin concentration in g/dL. This method provides fast, accurate results for monitoring hemoglobin levels in the blood.

Infection with the various plasmodial species was detected by microscopy on a thin smear and a thick drop. For the thick drop, slides were immersed in a solution of Giemsa for 10 to 15 minutes, then carefully rinsed and air-dried. The thin smears, spread out and fixed in methanol, were also stained with Giemsa for further analysis. Microscopic examination of the thick drop began with low magnification, followed by high magnification, enabling Plasmodiums to be identified on the basis of their characteristic shapes (rings, trophozoites, gametocytes) within the red blood cells. Examination of the thin smears enabled Plasmodium species to be identified on the basis of their distinctive morphologies.

Operational Definitions

The following operational definitions were used in this study:

- Malaria infection in parturients was defined by a composite indicator, including infections detected by a rapid diagnostic test (RDT) targeting the P. falciparum HRP2 antigen or by microscopic examination of a thick drop of blood.

- Maternal anemia was defined as hemoglobin (Hb) < 11 g/dL for pregnancies of 28 Weeks’ Amenorrhea (WA) or more, and hemoglobin < 10.5 g/dL for second-trimester pregnancies.

- Preterm Delivery (PD) was defined as a delivery between 28- and 37-weeks’ amenorrhea.

- Primiparity was defined as the first parturition, secondiparity as the second parturition, and multiparity as three or more parturitions.

Statistical data analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using R software version 4.4.1. Categorical variables were summarized in the form of frequencies and percentages. Calculations of the mean with standard deviations and the median with extremes were performed for quantitative variables. To measure the strength of association between variables, we calculated Odds Ratios (OR) and their 95% Confidence Intervals (CI). Hemoglobin levels were compared between two groups (malaria present/absent) using the Wilcoxon test. Distributions were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Logistic regression models were used to identify the various factors associated with maternal anemia. The final model was selected using Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) with a “forward” and “backward” approach. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

This study had been approved by the National Health Ethics Committee, under number 558/CNES/BN/ PMMF/2024. Free and informed consent was obtained and an identifier was assigned to all participants. The study was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with good clinical and laboratory practice.

RESULTS

Socio-demographic characteristics and clinical status of participants at admission, 246 parturients were eligible during the study period. However, only 199 were retained due to data availability. Tables 1and 2 present the socio demographic and clinical characteristics of the parturients included in the study.

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of parturients at inclusion

|

Characteristics |

n |

% |

|

Age (years) |

|

|

|

< 20 |

11 |

5,5 |

|

20 – 34 |

148 |

74,4 |

|

≥ 35 |

40 |

20,1 |

|

Mo Average ± Standard deviation |

28,3±6,4 |

|

|

Level of education |

|

|

|

Illiterate |

37 |

18,6 |

|

Primary |

18 |

9,1 |

|

Secondary |

144 |

72,4 |

|

Profession |

|

|

|

Household |

102 |

51,3 |

|

Self-employed |

66 |

33,2 |

|

Salaried |

31 |

15,6 |

Table 2 : Clinical (anamnestic) characteristics of parturients at inclusion

|

Chracteristics |

n |

% |

|

Gestational age (WA) |

|

|

|

? 37 |

27 |

13,6 |

|

37- 41 |

172 |

86,4 |

|

Parity |

|

|

|

Primiparous |

43 |

21,6 |

|

Secondiparous |

37 |

18,6 |

|

Multiparous |

119 |

59,8 |

|

Median (Min - Max) |

3 (1 – 12) |

|

|

Number of ANC follow-up visits |

|

|

|

None |

25 |

12,6 |

|

1 - 2 ANC visits |

37 |

18,6 |

|

3 or more ANC visits |

137 |

68,8 |

|

Median (Min - Max) |

3 (0 – 10) |

|

|

Fever during pregnancy |

|

|

|

No |

48 |

24,1 |

|

Yes |

151 |

75,9 |

|

Using LLIN |

|

|

|

No |

70 |

35,1 |

|

Yes |

129 |

64,9 |

|

Frequency of LLIN use (in a week) |

|

|

|

Never |

70 |

35,2 |

|

Rarely (less than 7 days/month) |

12 |

6,0 |

|

Often (less than 7 days/week) |

61 |

30,7 |

|

Always (7 days/7) |

56 |

28,1 |

|

IPT to MS |

|

|

|

No |

125 |

62,8 |

|

Yes |

74 |

37,2 |

|

Number of SP doses |

|

|

|

0 |

125 |

62,8 |

|

1 - 2 |

56 |

28,1 |

|

≥ 3 |

18 |

9 |

The results show that the majority of parturients were aged between 20 and 34 years (74.4%), with an average age of 28.3 ± 6.4 years. Most had attained secondary education (72.4%), while 18.6% were illiterate. More than half of parturients (51.3%) were housewives. Obstetrically, the majority of women went into labor with a gestational age of between 37 and 41 weeks’ amenorrhea (84.4%), while 13.6% delivered prematurely (< 37 SA). Over half the parturients were multiparous (59.8%).

A review of medical records revealed that 68.8% of women had attended at least three antenatal clinics (ANC), while 12.6% had had no medical check-ups at all during their pregnancy. Three quarters (75.9%) reported fever during pregnancy. With regard to the use of malaria prevention measures, 64.9% of women reported having a long-acting insecticide- treated net (LLIN). However, only 28.1% used it systematically (7 days/7), while 35.2% said they never used it. When it came to intermittent preventive treatment (IPT) with Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine (SP), around 62.8% of women claimed to have received no dose at all, while only 9% had received the recommended three doses.

Table 3: Logistic regression models identifying factors associated with maternal anemia in the study population

|

Characteristics |

Hb < 11g/dl |

Hb≥ 11g/dl |

OR goal [CI95%] |

p |

OR adjusted [CI95%] |

P |

|

n (%) |

n (%) |

|||||

|

Age (years) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

? 20 |

4 (9,5) |

17 (10,8) |

0,9 [0,2 ; 2,5] |

0,807 |

|

|

|

≥ 20 |

38 (90,5) |

140 (89,2) |

|

|

|

|

|

Education level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Illiterate |

13 (31,0) |

24 (15,3) |

2,5 [1,1 ; 5,4] |

0,023 |

2,5 [1,1 ; 5,9] |

0,035 |

|

Educated |

29 (69,0) |

133 (84,7) |

|

|

|

|

|

Gestational age (WA) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

? 37 |

12 (28,6) |

15 (9,6) |

3,8 [1,6 ; 8,9] |

0,002 |

3,7 [1,4 9,1] |

0,006 |

|

37 - 41 |

30 (71,4) |

142 (90,4) |

|

|

|

|

|

Parity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Primiparous |

7 (16,7) |

36 (22,9) |

0,7 [0,3 ; 1,6] |

0,383 |

|

|

|

Secondiparous and multiparous |

35 (83,3) |

121 (77,1) |

|

|

|

|

|

ANC follow-up |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

≤1 |

6 (14,3) |

28 (17,8) |

0,7 [0,3 ; 1,9] |

0,588 |

|

|

|

≥2 |

36 (85,7) |

129 (82,2) |

|

|

|

|

|

Fever during pregnancy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

37 (88,1) |

114 (72,6) |

2,8 [1,1 ; 8,5] |

0,044 |

|

|

|

No |

5 (11,9) |

43 (27,4) |

|

|

|

|

|

Malaria during pregnancy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive |

33 (78,6) |

105 (73,4) |

1,3 [0,6 ; 3,1] |

0,502 |

4,3 [1,9 ; 9,9] |

<0.001 |

|

Negative |

9 (21,4) |

38 (26,6) |

|

|

|

|

|

Malaria at delivery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive |

15 (35,7) |

21 (13,4) |

3,6 [1,6 ; 7,9] |

0,001 |

|

|

|

Negative |

27 (64,3) |

136 (86,6) |

|

|

|

|

|

IPT/SP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Less than 2 doses |

29 (69,0) |

114 (72,6) |

0,8 [0,4 ; 1,8] |

0,648 |

|

|

|

2 doses or more |

13 (31,0) |

43 (27,4) |

|

|

|

|

|

LLIN/pregnancy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Less than 7 days/week |

30 (71,4) |

113 (72,0) |

1,0 [0,5 ; 2,1] |

0,944 |

|

|

|

7days/7(always on LLIN) |

12 (28,6) |

44 (28,0) |

|

|

|

|

|

Occupation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Housewife |

20 (52,4) |

82 (52,2) |

0,8 [0,4 ; 1,7] |

0,596 |

|

|

|

Working |

22 (47,6) |

75 (47,8) |

|

|

|

|

Prevalence of Anemia and Malaria at Delivery

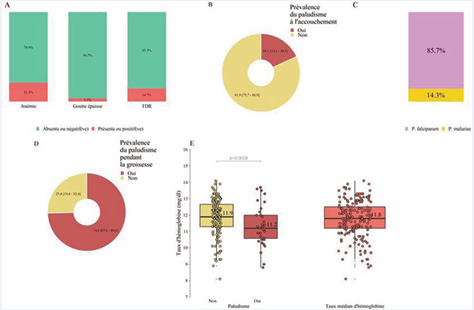

Overall, Plasmodium spp. were detected by RDT in 29 out of 199 participants and by thick drop in 7 out of 199, giving an estimated malaria prevalence of 18.1% [95% CI 13.1; 24.3] at the time of delivery (Figure 1A-B). Two species of Plasmodium spp. were identified at thin smear among infected participants, notably P. falciparum as the most prevalent species (85.7% [95% CI 42.0; 99.2]) followed by P. malariae (14.3% [95% CI 0.75; 57.9]) (Figure 1C). Overall, 74.6% of women had been diagnosed with malaria during pregnancy (Figure 1D). The median hemoglobin level at delivery was statistically different according to malaria status: 11.2 g/dL (8.3-13.9 g/dL) in parturients with malaria versus 11.9 g/dL (8.1-14.1 g/ dL) in parturients without malaria, with p= 0.0028 (Figure 1E), and the median overall hemoglobin level was 11.8 g/ dL, with extremes ranging from 8.1 g/dL to 14.1 g/dL. This allowed us to estimate the prevalence of maternal anemia at 21.1% [95% CI 15.8; 27.6] (Figure 1A).

Figure 1 : Prevalence of maternal anemia and malaria

Factors Associated with Maternal Anemia

Multivariate logistic regression modeling showed that maternal anemia was independently influenced by several factors, including the parturient’s level of education and medical history. Thus, illiteracy and diagnosis of malaria during pregnancy proved to be significant factors multiplying the risk of anemia by 2.5 for the former (aOR = 2.5 [95% CI 1.1; 5.9]; p = 0.035) and by 4 for the latter (aOR = 4.3 [95% CI 1.9; 9.9]; p ?0.001) in the women concerned. Furthermore, preterm delivery (? 37 weeks’ amenorrhea) was found to be a consequence significantly associated with anemia (adjusted OR = 3.7 [95% CI 1.4; 9.1]; p = 0.006). In contrast, prevention of malaria during pregnancy showed no statistically significant association with anemia (p > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of maternal anemia and identify associated factors in pregnant women in a malaria-endemic area.

Prevalence of Maternal Anemia and Malaria

This study enabled us to estimate the prevalence of maternal anemia and malaria at delivery in parturients admitted to the above-mentioned maternity hospitals. The prevalence of maternal anemia was 21.1% [95% CI 15.8; 27.6] and that of maternal malaria was 18.1% [95% CI13.1; 24.3], with Plasmodium falciparum the most prevalent species at 85.7%. These results confirm that maternal anemia and malaria remain a major, persistent public health problem among pregnant women living in areas with stable malaria transmission [9,10]. At least these prevalences are lower than those reported by other studies, such as Doumbo in Mali with a rate of 44.5% anemia and 52% malaria; the prevalence of anemia was 33% in the Vindhya series in India, it varied between 11 and 63% in the Bihoun series, depending on the degree of placental malaria infestation, and Oumaro reported a maternal malaria prevalence of 36.5 [21-24]. The prevalence of anemia was very high, at 76% in the Likilo et al., series in Kisangani [8]. In contrast, other studies have reported low prevalences of maternal malaria : Bamba with 4.7% in Burkina Faso ; 7.2% in the Massamba series in the Republic of Congo ; and Mudji who reported 9.7% malaria with 63% maternal anemia in Vanga, Kwilu [13,20,25]. Our results are superior to those of Kayiba et al. in Kinshasa, who reported a prevalence of 10.8% malaria and 14.9% maternal anemia [19]. These observed differences can be attributed to several factors, including geographical, environmental and nutritional variations or disparities, the study methodologies used, but also the effectiveness of malaria prevention and control programs in other settings,notably the distribution of insecticide- treated mosquito nets, intermittent preventive treatment with Sulfadoxine pyrimethamine and iron and folic acid supplementation during pregnancy [7,8,14,20,22,25]. In this study, we used the microscopic technique on peripheral blood to diagnose malaria, whereas in pregnant women living in endemic areas, parasites are typically sequestered in the placenta due to the cyto-adherence of parasitized red blood cells to placental tissue, and the density of available peripheral blood parasites is below the detection limit of microscopy, requiring highly sensitive molecular tools [11]. Plasmodium falciparum remains the most common species in areas of stable transmission, especially in pregnant women, due to its affinity with placental tissue [26,27].

Characteristics and Clinical History of the Study Population

The majority of participants were aged between 20 and 34 (74.4%), with an average age of 28. Women with secondary education were the most represented (72.4%), and most were multiparous (59.8%). Our results are similar to those of Biaou, who reported an average age of 27 years, with the majority being pauciparous (multiparous) [21,28], but differ from those of Oumaro in Niger with regard to educational level, with a high proportion of illiterate women (67.5%) [24]. Bamba reported an average age of 26 years, with the majority being uneducated (41.5%) [25]. In contrast, in Doumbo’s series, adolescents were the most represented with 28% [21]. The similarity of average age in most studies is explained by the fact that these are women of childbearing age, and the differences are explained by early marriage in some remote areas with a lack of education for girls; our study was carried out in the city, where girls’ studies are becoming increasingly encouraged. Over 68% of women had undergone at least 3 ANCs, a rate of 72% of 4 or more ANCs was reported in the Biaouseries [23], while in the Oumaro study, only 26% had undergone 3 ANCs [24].

Nearly 65% used LLINs, the same trend was observed in the Doumbo study (62%) [21], the regular use of insecticide-treated nets is the main large-scale preventive measure against malaria, particularly in regions where the endemic is high, this rate of use is superposable on ANC attendance (68%) because it is during these sessions that LLINs are distributed, although their use is often abused in most cases [20].

The IPTg-SP coverage rate was 37.2%, but only 9% of participants had received at least 3 doses of SP. This IPT coverage rate is significantly lower than those reported by other studies : 64, 8% and 22% for 3 doses ; 80% and 13% for 3 doses ; 31-34% for 3 doses and Mudji who reported 80% coverage with an average number of doses at 2.5 [13,20,24,28]. The 2023-2024 Demographic and Health Survey reported a 3-dose SP coverage rate of 16% for the whole province of Kasaï-Oriental. According to the same survey, ours is higher than that of Tanganyika province (7.8%) [15]. Differences in national malaria control program (NMCP) policies may explain these disparities. For example, some peripheral health zones are well supported compared with those in the city center, but overall IPT coverage remains very low in our area. More than three quarters (75.9%) of parturients mentioned a history of fever during pregnancy; several studies report that fever is the most common sign of malaria in endemic areas, and also contributes to maternal anemia [19,23,24].

Factors associated with maternal anemia in malaria endemic areas

Lack of education (illiteracy) and history malaria during pregnancy were factors associated with maternal anemia, and preterm delivery was a direct consequence, underlining the impact of anemia on perinatal health. Pregnancy makes women vulnerable to malaria infection, exposing them to anemia and death; Plasmodium falciparum can localize in the placenta and contribute to maternal anemia even in the absence of parasites in peripheral maternal blood [11]. Malaria in pregnant women is characterized by maternal anemia, and preterm delivery is one of the consequences [19,25,28].

IPT is not only an effective but also, and above all, an inexpensive means of preventing malaria-related maternal anemia. Numerous studies have shown the benefit of IPT and LLIN in the prevention of placental malaria and its effects on maternal anemia and birth weight [19 21,24,25,28]. On the other hand, we did not note any impact of IPT-SP on maternal anaemia in this study. Our results concur with those of Labama in Kisangani [18], but contrast with those of Kayiba, who noted a beneficial effect of IPT-SP on maternal anemia and preterm delivery in Kinshasa, although the prevalence of maternal malaria was not reduced by this prevention ; This could be explained by the emergence of Plasmodium falciparum resistance to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine [19,29]. It should be noted, however, that we reported a very low IPT coverage rate to assess the benefit, and also the notion of iron-folate supplementation was not taken into account in this study for lack of reliable data. Nevertheless, these results suggest a reassessment of these measures in settings endemic to Plasmodium falciparum, which is clearly becoming increasingly resistant to antimalarial drugs.

CONCLUSION

The results of our study show that anemia is a major problem among pregnant women in Mbujimayi, significantly influenced by the low level of education, and that malaria is the major source of anemia in an environment endemic to Plasmodium spp. Maternal anemia thus adds to perinatal morbidity through the prematurity associated with it. On the other hand, the emergence of resistance to SP and other antimalarial drugs, which has yet to be demonstrated in our environment but has already been documented in other parts of the country, would threaten the hopes placed in this preventive method. In the light of these results, we believe that raising women’s awareness of the problem of malaria and its consequences, and reinforcing the NMCP ‘s actions in the field, could encourage pregnant women to adhere to IPT with SP and to the judicious use of LLINs in the town of Mbujimayi, in order to improve maternal and infant health

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993-2005: WHO global database on anaemia. / Edited by Bruno de Benoist, Erin McLean, Ines Egli and Mary Cogswell. 2008 ;40.

- Ntuli TS, Mokoena OP, Maimela E, Sono K. Prevalence and factors associated with anaemia among pregnant women attending antenatal care in a district hospital and its feeder community healthcare centre of the Limpopo Province, South Africa. J Family Med Prim Care. 2023; 12: 2708-2713.

- Afeworki R, Smits J, Tolboom J, van der Ven A. Positive Effect of Large Birth Intervals on Early Childhood Hemoglobin Levels in Africa Is Limited to Girls: Cross-Sectional DHS Study. PLoS One. 2015; 10: e0131897.

- Abay A, Yalew HW, Tariku A, Gebeye E. Determinants of prenatal anemia in Ethiopia. Arch Public Health. 2017; 75: 51.

- Carneiro IA, Smith T, Lusingu JP, Malima R, Utzinger J, Drakeley CJ. Modeling the relationship between the population prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria and anemia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006; 75 :82-89.

- Gebrerufael GG, Hagos BT. Anemia Prevalence and Risk Factors in Two of Ethiopia’s Most Anemic Regions among Women: A Cross- Sectional Study. Kumar M, éditeur. Adv Hematology. 2023 :1-9.

- Animut K, Berhanu G. Determinants of anemia status among pregnant women in ethiopia: using 2016 ethiopian demographic and health survey data; application of ordinal logistic regression models. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2022; 22 :663.

- Jeremy LO, Opara A, Agasa B, Bosunga K, Likwekwe K. Risk factors associated with anemia among pregnant women in Kisangani in D.R.Congo. Int J Recent Sci Res. Int J Recent Sci Res. 2018; 9: 26015- 26021

- Unger HW, Rosanas-Urgell A, Robinson LJ, Ome-Kaius M, Jally S, Umbers AJ, et al.Microscopic and submicroscopic Plasmodium falciparum infection, maternal anaemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes in Papua New Guinea: a cohort study. Malar J. 2019; 18: 302.

- Kalinjuma AV, Darling AM, Mugusi FM, Abioye AI, Okumu FO, Aboud S, et al. Factors associated with sub-microscopic placental malaria and its association with adverse pregnancy outcomes among HIV- negative women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: a cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2020; 20: 796.

- Shulman CE, Dorman EK. Importance and prevention of malaria in pregnancy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2003; 97: 30-35.

- Menendez C. Malaria during pregnancy. Curr Mol Med. 2006; 6: 269-273.

- Massamba JE, Djontu JC, Vouvoungui CJ, Kobawila C, Ntoumi F. Plasmodium falciparum multiplicity of infection and pregnancy outcomes in Congolese women from southern Brazzaville, Republic of Congo. Malar J. 2022; 21: 114.

- WHO. WHO policy brief for the implementation of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy using sulfadoxine- pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP) World Health Organization Geneva, Switzer land; 2013.

- Demographic and Health Survey DHS-DRC III 2023-2024. InDemocratic Republic of Congo. 2024.

- Kayiba NK, Tshibangu-Kabamba E, Rosas-Aguirre A, Kaku N, Nakagama Y, Kaneko A, et al. The landscape of drug resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in the Democratic Republic of Congo: a mapping systematic review. Trop Med Health. 2023; 51: 64.

- Darriet F, editor. Impregnated mosquito nets and mosquito resistance to insecticides. IRD Éditions; 2007; 116.

- Noël LO, Jean-Didier BN, Mike-Antoine MA, Joris LL, Jean-Pascal MO. Intermittent Preventive Treatment in Pregnancy with Sulphadoxine- Pyrimethamine Does Not Have Effect on Maternal Hemoglobin at Delivery and Birth Weight in Kisangani, Democratic Republic of Congo. JBM. 2019; 07: 168-180.

- Kayiba NK, Yobi DM, Tchakounang VRK, Mvumbi DM, Kabututu PZ, Devleesschauwer B, et al. Evaluation of the usefulness of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy with sulfadoxine- pyrimethamine in a context with increased resistance of Plasmodium falciparum in Kingasani Hospital, Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Infect Genet Evol. 2021; 94: 105009.

- Mudji J, Yaka PK, Olarewaju V, Lengeler C. Prevalence and risk factors for malaria in pregnancy in Vanga, Democratic Republic of Congo. Afr J Reprod Health. 2021; 25: 14-24.

- Doumbo, S, Ongoiba, O.A, Doumtabé, D.et al. Prévalence de Plasmodium falciparum, de l’anémie et des marqueurs moléculaires de la résistance à la chloroquine et à la sulfadoxine-pyrim éthamine chez les femmes accouchées à Fana, Mali. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 2013; 106: 188-192.

- Vindhya J, Nath A, Murthy GVS, Metgud C, Sheeba B, Shubhashree V, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of anemia among pregnant women attending a public-sector hospital in Bangalore, South India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019; 8: 37-43.

- Bihoun B, Zango SH, Traoré-Coulibaly M, Valea I, Ravinetto R, Van Geertruyden JP, et al. Age-modified factors associated with placental malaria in rural Burkina Faso. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022; 22: 248.

- Oumarou ZM, Lamine MM, Issaka T, Moumouni K, Alkassoum I, Maman D, et al. Infection palustre de la femme enceinte à Niamey au Niger [Malaria infection during pregnancy in Niamey, Niger]. Pan Afr Med J. 2020; 37: 365. French.

- sulfadoxine--pyriméthamine du paludisme chez les femmes enceintes: efficacité et observance dans deux hôpitaux urbains du Burkina Faso [Intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine--pyrimethamine for malaria in pregnant women: efficacy and compliance in two urban hospitals in Burkina Faso]. Pan Afr Med J. 2013; 14: 105.

- Kayiba NK, Nitahara Y, Tshibangu-Kabamba E, Mbuyi DK, Kabongo- Tshibaka A, Kalala NT, et al. Malaria infection among adults residing in a highly endemic region from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Malar J. 2024; 23: 82.

- Anchang-Kimbi JK, Achidi EA, Nkegoum B, Sverremark-Ekström E, Troye-Blomberg M. Diagnostic comparison of malaria infection in peripheral blood, placental blood and placental biopsies in Cameroonian parturient women. Malar J. 2009; 8: 126.

- Biaou COA, Kpozehouen A, Glèlè-Ahanhanzo Y, Ayivi-Vinz G, Ouro- Koura AR, Azandjèmé C. Traitement préventif intermittent à la sulfadoxine-pyriméthamine chez la femme enceinte et effet sur le poids de naissance du bébé: application de la politique à 3 doses en zone urbaine au Sud Bénin en 2017 [Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine- based intermittent preventive treatment in pregnant women and its effect on birth weight: application of 3-dosing regimen in the urban area of South Benin in 2017]. Pan Afr Med J. 2019; 34: 155.

- Likwela JL, D’Alessandro U, Lokwa BL, Meuris S, Dramaix MW. Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine resistance and intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy: a retrospective analysis of birth weight data in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Trop Med Int Health. 2012; 17: 322-329.