Implementation of Machine Learning for Identification of Familial Hypercholesterolemia Requires a ŌĆ£Human in the LoopŌĆØ: Lessons Learned from a Novel Outreach Program in an Academic Health System

- 1. Heart and Vascular Center, Section of Cardiovascular Medicine, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, USA

- 2. The Family Heart Foundation, USA

- 3. Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth, USA

- 4. Department of Population Health, University of Kansas School of Medicine, USA

Citation

Hennessey KC, Bardach SH, Sturke T, Vaze VS, Forcino R, et al. (2025) Implementation of Machine Learning for Identification of Familial Hypercholesterolemia Requires a “Human in the Loop”: Lessons Learned from a Novel Outreach Program in an Academic Health System. Ann Vasc Med Res 12(2): 1192.

Introduction

The vast majority of individuals with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) remain undiagnosed despite a prevalence of approximately 1:250 – 1:300 in the general population [1-3]. If left untreated, FH results in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) as early as age 30 and increases the risk of experiencing a premature cardiac event by 20-fold [1-2]. Most individuals with FH respond to lipid lowering drug therapy, thereby, reducing their risk of a cardiac event by up to 80% [1-2]. Machine learning models (MLM) have been developed and validated to identify undiagnosed individuals with FH based on deidentified electronic medical record (EMR) data; however, strategies to integrate them into clinical care are lacking. Our team integrated the Flag Identify Network and Deliver FH (FIND-FH®) MLM developed by the Family Heart Foundation (FHF) into a direct-to-patient outreach process at Dartmouth Health (DH) system, an academic medical center with a local population enriched for FH due to French-Canadian ancestry [4-12]. Our experience highlights the role clinicians play in implementing novel diagnostic strategies and provides some practical insights for those endeavoring to use MLM in their clinical practice [6].

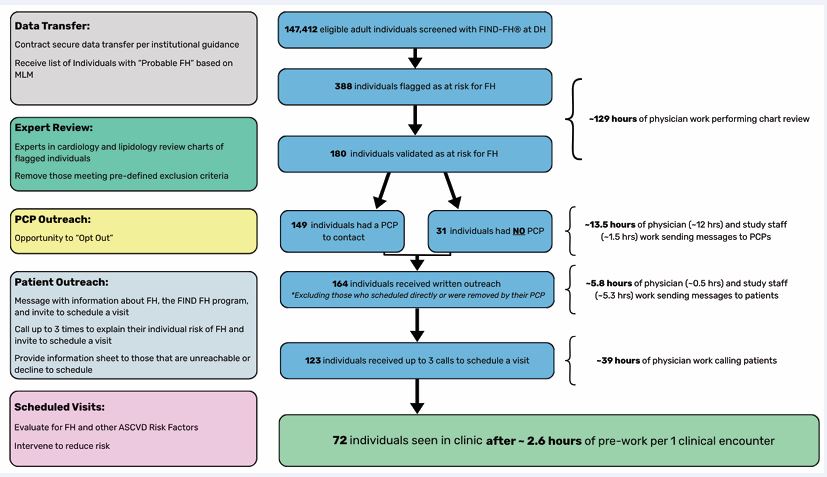

The process of using a machine learning model for outreach [Figure A],

begins with contracting terms of use and secure data transfer. Prior to using FIND-FH®, a de identified, secure data transfer was completed between DH and the FHF, where the model was run. Coordination between our health system and FHF required consultation with information technology specialists and approval at a system level. The FIND-FH® model was run in April 2021 and the EMR data of individuals flagged by the model were returned to DH and re-identified. Outreach design and implementation was performed from January 2023 to March 2024 after obtaining funding for outreach design and expert chart review.

FIND-FH® was applied to 147,412 unique patient records and identified 388 adult patients at risk for FH. Lipidologists and cardiologists used FH clinical criteria to review the charts of flagged individuals and validate the model in our clinical environment. FH is clinically diagnosed based on a weighted combination of physical findings, personal or family history of hypercholesterolemia, premature ASCVD, and the low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentration, especially untreated. Patients were excluded from outreach if they had an established diagnosis of FH, were established in the lipid clinic, had insufficient information to suspect FH, had a low likelihood of FH, had moved, were deceased, or had alternative medical priorities at the time of review. We found that the EMR often lacked one or more of the necessary data elements including 1) the International Classification of Diseases code E78.01 to exclude patients known to have FH, 2) a detailed family history with the age of onset of ASCVD, 3) a physical exam noting pertinent findings including arcus senilis prior to age 45, xanthelasma, or tendon xanthoma, 4) LDL-C values, and 5) patient vital status, including whether they continued to receive care in our health system. Reviewing free text and scanned media was necessary for thorough chart review but time consuming. Allowing for 20 minutes per chart, physician data abstractors spent approximately 129 hours on the process of chart review for all 388 flagged individuals.

We found that expert review removed more than half of the flagged patients from outreach [54%; 208/388] including 115 [30%] individuals who had a low suspicion for FH with a median LDL of 122.5 mg/dL (interquartile range 98.6-143.8 mg/dL) and 32 [15%] that had insufficient information to suspect FH. By removing patients less likely to have FH, expert review reduced the patient burden associated with potential false positives, reduced the outreach workload, and increased community trust in the process of identification; however, the review process was labor-intensive and introduced delays between identification and outreach. The higher median LDL-C [172 mg/dL (interquartile range 132-216 mg/dL) vs. 134 mg/dL (interquartile range 102-154 mg/ dL)], and likelihood of having an LDL-C greater than 190 mg/dL [37% vs. 7%] among those selected for outreach compared to those excluded from outreach suggest that expert review identified the patients most appropriate for contact by clinical criteria.

A total of 180 [46%; 180/388] individuals were selected for outreach. The outreach process was designed with a step to allow primary care providers (PCPs) to “opt out” of the program. This approach removed provider nonresponse as a barrier to participation and respected feedback from PCPs and members of the public that PCPs should be involved. A total of 149 patients had a DH PCP to notify about the elevated risk of FH. Among PCPs, 105 were able to receive a message via the EMR. Physicians on the outreach team spent approximately 7 minutes per message to personalize the communication, resulting in 12 hours of labor. The remaining providers received a standardized letter paid for and mailed by the research support team, for an additional 1.5 hours of work. Seventy percent (105/149) of PCP messages did not receive a response. Among 44 PCP responders, only 4 objected to participation. Some PCPs discussed the program with their patients resulting in a total of 8 scheduled patients.

After PCP notification, a total of 164 individuals remained eligible for direct patient outreach. Individuals were first contacted in writing with information about FH and an invitation to schedule a visit, resulting in 7 scheduled visits. The majority received a letter mailed by study support staff [98%, 160/164], and four patients received a personalized EMR message from a physician. Assuming 2 minutes to address and mail each letter, the study team performed about 5.3 hours of work and team physicians spent 30 minutes messaging the final four patients directly via the EMR. After providing written communication, physicians with expertise in cardiovascular medicine and lipidology called each individual up to 3 times to discuss the program and schedule a visit. Ultimately, 236 total phone calls were made by a physician team member to achieve 53 additional scheduled visits. Allowing an average of 10 minutes to review the chart, complete the call, and track the attempt, this step added about 39 hours of physician work.

The outreach process yielded a total of 72 clinical visits [19%; 72/388] and 58 new diagnoses of possible/probable or definite FH [15%; 58/388] for a detection rate of 1:6.69. While this substantially improves on the rate of diagnosis when screening the general population (1:250, 0.4%), the validation and outreach process was labor intensive (~187 hours of labor to achieve 72 clinical visits, or 2.6 hours of pre-work per clinical encounter).

After a single visit, a majority of patients 62 (86%) had changes to their lipid lowering therapy, weight management, antihypertensives, or diabetes regimen, or referrals to smoking cessation or nutrition regardless of their diagnosis, highlighting a substantial opportunity to improve preventative care in this selected population of individuals at high risk for ASCVD.

Overall, our experience highlights the strengths and potential pitfalls of machine learning-based outreach programs. Through expert review, we found that the rate of detection of possible FH using the FIND-FH® MLM in our cohort was lower than expected based on validation studies but superior to general population screening. Expert review and outreach increased PCP and community trust in the process of identification but introduced a significant workload on team physicians. Future efforts should consider methods to facilitate expert review, such as providing the elements flagged by the MLM. Improving the accuracy of machine learning identification, EMR interoperability, and standardization of key data elements will enhance the scalability of these types of programs. Once patient identification and chart review are reliable and reproducible, non-physician team members could be leveraged to perform data abstraction and some elements of outreach. Calls from study team physicians were the highest yield in terms of scheduling, so future outreach should have clinicians focus on patient calls and visits. Incorporating MLM based “flags” in the EMR at the time of a clinical visit with a member of the patient’s usual care team may negate the need for outreach from an unfamiliar provider. MLMs hold promise for improving identification of individuals with FH and reducing their risk of premature heart attack and stroke, however, the pre-work required to validate MLM with expert chart review and perform patient outreach with physicians is cost prohibitive in an environment where clinician reimbursement and productivity are determined based on relative value units (RVU). Importantly, the lessons learned about patient activation in patients with FH will be relevant to a larger population of patients with ASCVD and hypercholesterolemia who are not at their LDL goal. More work is needed to build confidence in MLM for identification of hypercholesterolemia in the clinical environment and allow seamless integration of these tools into clinical practice to improve ASCVD outcomes more broadly.

REFERENCES

- McGowan MP, Hosseini Dehkordi SH, Moriarty PM, Duell PB. Diagnosis and Treatment of Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019; 8: 24.

- Hu P, Dharmayat KI, Stevens CAT, Sharabiani MTA, Jones RS, Watts GF, et al. Prevalence of familial hypercholesterolemia among the general population and patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Circulation. 2020; 141: 1742-1759.

- Beheshti SO, Madsen CM, Varbo A, Nordestgaard BG. Worldwide prevalence of familial hypercholesterolemia: meta-analyses of 11 million subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020; 75: 2553- 2566.

- Banda JM, Sarraju A, Abbasi F, Parizo J, Pariani M, Ison H, et al. Finding missed cases of familial hypercholesterolemia in health systems using machine learning. NPJ digital Med. 2019; 11: 23.

- Myers KD, Knowles JW, Staszak D. Precision screening for familial hypercholesterolaemia: a machine learning study applied to electronic health encounter data. Lancet Digit Health. 2019; 1: e393-e402.

- Hennessey KC, Bardach SH, Sturke T, Vaze VS, Kalkur RS, PrinceAJ, et al. Implementation of a machine learning model and direct-to-patient outreach program for targeted screening for familialhypercholesterolemia. 2025; 19: 1029-1036.

- Mszar R, Buscher S, Taylor HL, Rice-DeFosse MT, McCann D. Familial hypercholesterolemia and the founder effect among Franco- Americans: a brief history and call to action. CJC Open. 2020; 2: 161- 167

- Myall, J. Franco-American Ancestry by County.

- Hobbs HH, Brown MS, Russell DW, Davignon J, Goldstein JL. Deletion in the gene for the low-density-lipoprotein receptor in a majority of French Canadians with familial hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 1987; 317: 734-737.

- Couture P, Morissette J, Gaudet D, Vohl MC, Gagné C, Bergeron J, etal. Fine mapping of low-density lipoprotein receptor gene by genetic linkage on chromosome and study of the founder effect of four French Canadian low-density lipoprotein receptor gene mutations. Atherosclerosis. 1999; 143: 145-151.

- Couture P, Vohl MC, Gagné C, Gaudet D, Torres AL, Lupien PJ, et al. Identification of three mutations in the low-density lipoprotein receptor gene causing familial hypercholesterolemia among French Canadians. Hum Mutat Suppl. 1998; 1: S226-231.

- Simard J, Moorjani S, Vohl MC, Couture P, Torres AL, Gagné C, et al. Detection of a novel mutation (stop 468) in exon 10 of the low-density lipoprotein receptor gene causing familial hypercholesterolemia among French Canadians. Human Molecular Genetics. 1994; 3: 1689-1691.