Molecular Epidemiology of Human Enterovirus B in Children with Acute Flaccid Paralysis from Five West African Countries

- 1. Virology Department, Institut Pasteur de Dakar, Senegal

- 2. World Health Organisation country office in Mauritania, Route de la Corniche Ouest, Republic of Mauritania

- 3. Ministry of Health of Mauritania, Avenue Gamel Abdel, Republic of Mauritania

- 4. World Health Organisation country office in Guinea-Bissau, Avenue Pensa Na Isna Bissau, Republic of Guinea-Bissau

- 5. Ministry of Health and Public hygiene of Guinea, G77P+56P Boulevard de Commerce, Republic of Guinea

- 6. World Health Organisation country office in Guinea, G8Q8+JC6, Corniche N, Republic of Guinea

- 7. World Health Organisation country office in The Gambia, Private Mail Bag, Republic of The Gambia

- 8. Ministry of Health and Social Welfare of the Gambia, the Quadrangle, Banjul, Republic of the Gambia

- 9. Ministry of Health of Social Actions of Senegal, Fann Résidence, Rue Aimé Césaire, Senegal

- 10. World Health Organisation country office in Senegal, 19 Lotissement Ngor-Extension Zone 10, Almadies, Senegal

- 11. World Health Organisation, Inter-Country Support Team for Western Africa, Burkina Faso

- 12. World Health Organisation regional office in Africa, Cité du Djoué, 06 Brazzaville, Republic of Congo

- 13. The Polio Eradication Department, World Health Organization, Avenue Appia 20, Switzerland

- #. These authors participated equally to this study as first author

- $. These authors participated equally to this study

Abstract

Enterovirus genus includes many viruses that are pathogenic for humans and most of the studies focusing on the distribution of Non-Polio Enteroviruses (NPEV) were conducted in Asia, Europa and in the Americas. However, only scarce data on the epidemiology of Enterovirus are available from Africa. To assess the molecular epidemiology of non-polio enteroviruses and human parechoviruses in West Africa, we investigated the genetic diversity of isolates identified in stool samples from under 15 years-old children with acute flaccid paralysis and living in five countries over a one-year period. Cell-culture isolates were first confirmed using a pan-enterovirus Reverse-transcriptase real-time quantitative PCR assay. The second-line testing included a screening of those isolates with a panel of assays targeting the enterovirus D68, enterovirus A71, Coxsackievirus A6, Coxsackievirus A16, echovirus species, human rhinovirus and human parechovirus. We found 417 (17.6 %) NPEV isolates from 2361 stool samples corresponding to specimens from 269 patients. In addition, echoviruses were identified in all countries with higher detection rate (86%). Genetic characterization of the VP1 coding region of echoviruses showed 21 genotypes of human enterovirus B including 17 genotypes of echoviruses, 1 Coxsackievirus B2, 1 Coxsackievirus A9, 1 enterovirus B75 and 1 enterovirus B84. In addition, the phylogenetic data exhibited a sub-regional clustering of enterovirus B species in West Africa. Our data provided new insights in the molecular epidemiology of NPEV in West Africa and could be useful for proper implementation of future vaccination. In addition, effective programs for genomic surveillance of enteroviruses are urgent needs in Africa

Keywords

• Acute Flaccid Paralysis

• Human Enteroviruses B

• Echovirus

• West Africa

• 2021

CITATION

Ndiaye N, Thiaw FD, Djimadoum HN, Diakité ML, Biai S, et al. (2024) Molecular Epidemiology of Human Enterovirus B in Children with Acute Flaccid Paralysis from Five West African Countries. Clin Res Infect Dis 8(1): 1065.

INTRODUCTION

Belonging to the Picornaviridae family, Enterovirus (EVs) are ubiquitous non-enveloped, icosahedral-capsid viruses, with a worldwide distribution [1]. Mainly transmitted to humans by faecal-oral route [1], EVs are responsible for various clinical manifestations ranging from mild and unnoticed non-specific acute infections (Aseptic Meningitis (AM), upper respiratory tract infections, skin infections, etc), specific (Hand Foot and Mouth Disease) to chronic forms (chronic meningoencephalitis in patients with agammaglobulinemia, post-poliomyelitis syndrome, chronic myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathies, insulin-dependent diabetes, etc) [2]. Other modes of transmission such as respiratory and maternal-fetal routes have also been reported [3]. The EVs genome is a single-stranded positive RNA of approximately 7.5 kilobases in length, flanked by 5′ and 3′ Untranslated Regions (UTRs) [4]. EVs have been divided into 12 distinct types of Enteroviruses (A-L) and Rhinoviruses (RV) A-C [5]. In humans, only RV species A-C and EV species A-D were previously found [5]. Human Enterovirus (EV) species include polioviruses (PV), Coxsackievirus A (CVA), Coxsackievirus B (CVB) and Echoviruses (EchoV) and newly identified EV [3].

EVB are the most distributed species worldwide [6] and have been described as the major causative agent of Central Nervous System (CNS) infections. Several outbreaks of aseptic meningitis

[7] involved the CVB species, the CVA9 and the EchoV types 4, 6, 9, 11, 13, 18 and 30 [8]. However, members of the specie A such as EVA71, CVA6 and CVA16 and specie D such as EVD68 have been involved in recent outbreaks of fatal Hand Foot and Mouth Disease (HFMD) and respiratory disease, respectively [9]. In addition, to date, Human Rhinoviruses (HRV) represent major causes of respiratory illnesses leading to crucial economic problems due to clinical morbidity overloading the health systems [10]. During the past four years, Human Parechoviruses (HPeV) previously classified into the EVs, were also considered as the second most common viral cause of Central Nervous System (CNS) infections [11,12]. However, most of the HPeV infections are currently underdiagnosed due to the limited access to diagnostic tools, particularly in low and middle-income countries.

Traditionally, detection of EV relied on identification of a positive viral culture from stool, nasopharyngeal swab or cerebrospinal fluid samples [13]. Recently, this approach has been largely replaced by viral RNA amplification methods such as reverse transcriptase Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR), which is faster and more sensitive [14]. In addition, sequencing of the VP1 gene is mostly used for the EV genotyping as it provides a perfect correlation with the genotype of the strains and an excellent discrimination of all taxonomic ranks (from species to variants) [15].

In Africa, only some studies focusing on the prevalence of EV have been conducted [16-18] and those in environmental samples showed a predominance of Enterovirus C species [19]. Herein, we report the prevalence and molecular epidemiology of EV species and HPeV in children with Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP) from five West African countries, over a one-year surveillance period.

DATA COLLECTION AND VIRUS ISOLATION

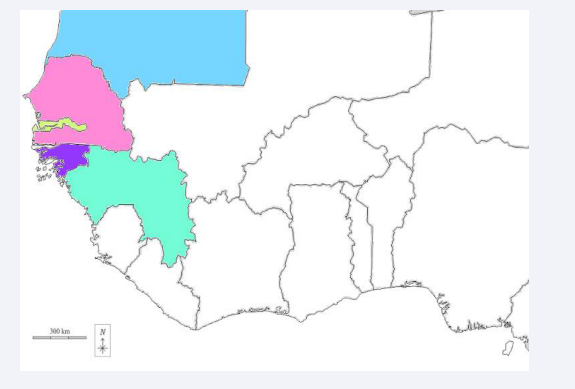

This study was conducted throughout five West African country (Figure 1) in 185 medical districts and 52 provinces for AFP case surveillance.

Figure 1: Map showing the five West African countries included in our study: Senegal (pink), Guinea (Green), Mauritania (blue), Guinea Bissau (Purple) and Gambia (yellow).

From January to December 2021, a total of 2361 stool samples were collected from 1261 patients under 15 years old with AFP including 44.6% (n = 563), 37.4% (n =471), 13.2% (n = 166), 2.5% (n = 32) and 2.3% (n = 29) cases from Senegal, Guinea, Mauritania, Guinea Bissau and Gambia, respectively. All stool samples were sent to the WHO-accredited Regional Reference Polio Laboratory in Senegal for processing according to the WHO standard procedures for poliovirus isolation [20].

Primary stools from AFP cases were treated using chloroform and stool suspensions were inoculated in both RD and human poliovirus receptor CD155 expressing recombinant murine (L20B) cell lines. For samples showing no Cytopathic Effect (CPE) after 5 days, a second passage in the same cell line was done and cells were monitored for CPE during the next 5 days. Samples with no CPE in both cell lines, even after the blind passage, were considered negative whereas, L20B-positive isolates were classified as suspected poliovirus and subjected them to the intratypic differentiation. Only supernatants producing CPE in RD cells and not in L20B cells were considered as Non-Polio Enteroviruses (NPEV). These RD-positive supernatants were then harvested and kept frozen (-200C) until use. Overall, NPEV were isolated in 422 stool samples (18.10%) and the highest of were found in Senegal with (49.5%; N = 209).

RNA Extraction and Molecular Detection

For AFP cases with NPEV-positive supernatants from both two-stool samples, only one was selected for the extraction. The viral genome (RNA) was extracted from 200µL using the QIAmp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Extracted RNA was eluted in 60µL of nuclease-free water and stored at -80°C until use. NPEV isolates were confirmed by TaqMan real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) using a pan- enterovirus (panEV) RT-PCR assay with the qScript™ XLT One- Step RT-PCR (Quanta Bio, Beverly, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In addition, differential singleplex RT qPCR assays for specific detection of EchoV [21]; EVA71 [22], CVA6 [23], CVA16 [24], EVD68 [25], HRV [26], and HPeV [27] were performed using specific primers and probe for each virus genus. Experiments were performed using the CFX96 Real-Time PCR system (Bio-Rad, Singapore). Positive RNA was stored at -80°C until further testing.

VP1 Gene Amplification

EchoV-positive RNA with Ct values lower than 25 were selected. The cDNA was synthetized using random hexamers with the Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific™ Vilnius, Lithuania). Amplicons of the VP1 region were then generated using The GoTaq® DNA Polymerase kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) for nested PCR method using pan-enterovirus published primers 222 and 224 that generate a 762bp nucleotide PCR product from the VP3-VP1 coding region as previously described [28]. PCR was carried out in a 50μL reaction volume containing 5μL of the cDNA product, 10μL of the PCR buffer (Promega), 4μL of MgCl2, 1.2μL of dNTP (10mM), 1μL each of 20μM 224 forward primer (5’GCIATGYTIGGIACICAYRT 3’), 222 reverse primer (5’CICCIGGIGGIAYRWACAT 3’) and 5μL of GoTaq® DNA Polymerase (5 u/μL). This reaction mixture was amplified using the following conditions: 3 minutes at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 30 seconds at 95°C, 30 seconds at 45°C and 1 minute at 72°C, plus a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. In order to avoid cross-contamination, a negative control with all the components of the reaction except for the template was included in the RT-PCR. PCR products size were verified using electrophoresis with 1% agarose gel and Bromide Ethidium staining, and UV visualization.

VP1 Gene Sequencing

Amplicons of the VP1 gene were quantified using the dsDNA High Sensitivity Kit on a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher). Amplicons were barcoded using the Rapid Barcoding Kit 110.96 with MRT001 expansion (Oxford nanopore technology). The pooled libraries were then purified and sequenced on a Minion MK1B instrument (Oxford nanopore technology) for 72 hours. Basecalled passed reads were analysed using the “Genome detective virus tool” program (version 2.40) and the generated consensus sequences were confirmed with the web-based “Enterovirus Genotyping Tool” platform. The obtained sequences were subjected to BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast. cgi) for identification of the closest sequence previously available in GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Phylogenetic Analyses

Multiple alignments of our dataset including the newly characterized VP1 sequences and 60 sequences previously available from Genbank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) were performed using Bioedit version 7.2.5 [29]. The Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree based on partial VP1 sequences was inferred using IIQ-TREE (version 1.6.12) for 1,000 replications [30]. The ML tree topology was visualized with Figtree (version 1.4.4) [31]. Nodes were supported by Bootstrap values.

Statistical Analysis

To assess the possible influence, data analysis was performed using RStudio software version 4.1.3 (RStudio, Boston, MA). The Fisher or Chi-square test test was used to compare the distribution with respect to sex and age groups. The age group of 0-5 years was used as a reference. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all the analyses.

RESULTS

Geographical Distribution and Demographic Characteristics

The age of the patients varies from 3 months to 15 years. The overall sex ratio in our population study was 1.2 with 4.4% missing data (n = 55). Male sex was more representative (660/546, p = 0.2993) in the same way children under 10 years were the most representative and accounted for 77.7% (n = 937) when compared to the other age groups (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of patients with AFP cases surveillance included in our study.

|

Features |

Senegal |

Guinea |

Mauritania |

Guinea Bissau |

Gambia |

Total |

P-Value |

|

(n = 563) |

(n = 471) |

(n = 166) |

(n = 32) |

(n = 29) |

(n = 1261) |

|

|

|

Gender % |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.2993 |

|

Female |

46.4 % (n = 261) |

42.7% (n = 201) |

37.4% (n = 62) |

37.5% (n = 12) |

34.5% (n = 10) |

43.3% (n = 546) |

|

|

Male |

53.6% (n = 302) |

48% (n = 227) |

58.4% (n = 97) |

50% (n = 16) |

65.5% (n = 19) |

52.3% (n = 660) |

|

|

Missing |

0 |

9.3% (n = 44) |

4.2% (n = 7) |

12.5% (n = 4) |

0 |

4.4% (n = 55) |

|

|

Age % |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2x10-16 |

|

0-5 years |

79.8% (n = 449) |

79.6% (n = 340) |

72.3% (n = 115) |

67.8% (n = 19) |

48.2% (n = 14) |

77.7% (n = 937) |

|

|

5-10 years |

14.2% (n = 80) |

15.7% (n = 67) |

20.1% (n = 32) |

14.3% (n = 4) |

27.6% (n = 8) |

15.8% (n = 191) |

|

|

10-15 years |

6% (n = 34) |

4.7% (n = 20) |

7.6% (n = 12) |

17.9% (n = 5) |

24.1% (n = 7) |

6.5% (n = 78) |

|

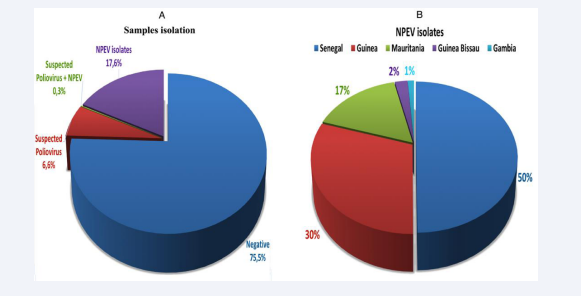

Of the 2361 samples processed, NPEV were isolated from 417 stool samples (17.6%), corresponding to specimens from 269 patients (Figure 2A). In addition, the highest numbers of NPEV was recorded in Senegal and Guinea with 208 (50%) and 125 (30%), respectively (Figure 2B).

Figure 2: Proportion of NPEV-positive isolates among the total number of samples received over 2021 (A) and their repartition per country (B).

Temporal Distribution of NPEV-Positive Samples

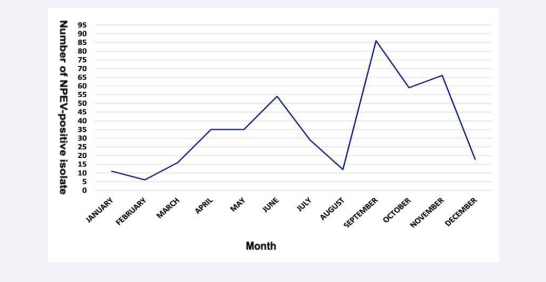

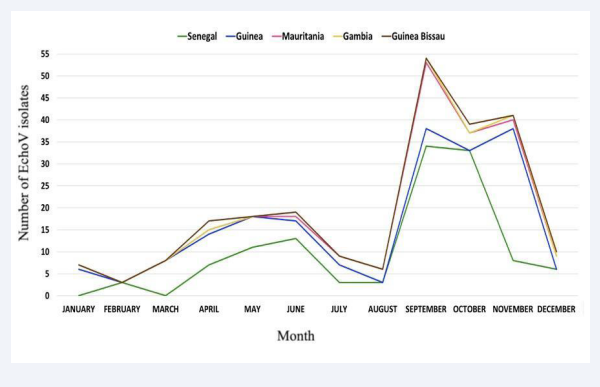

Although the study covered only a one-year surveillance period, a seasonality was observed for the circulation of NPEV in West Africa. Two peaks were observed: one from February to July (dry season) and another from August to November (rainy season (August-October) and beginning of the dry season with cold temperatures (November-December)) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Monthly distribution of NPEV-positive isolates from children with AFP in West Africa over 2021.

Molecular Testing

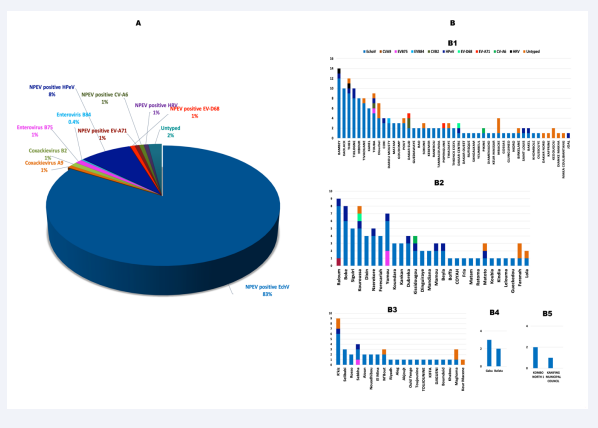

Out of the 269 NPEV-positive isolates from patients selected, a total of 268 (99.6%) were confirmed by RT-qPCR. Most of these isolates were collected in Senegal (n = 147), followed by Guinea (n= 75), Mauritania (n = 39), Guinea Bissau (n = 5) and The Gambia (n = 3). Specific molecular typing revealed a predominance of EchoV with a positivity rate of 86% (n = 231), followed by HPeV with 8% (n = 23). EVD68, EVA71, CVA6 and HRV exhibited both a prevalence of 1% (Figure 4A). Six isolates (2%) were untyped using our panel. EchoV were identified in all countries: Senegal Guinea, Mauritania, Guinea Bissau and Gambia (n = 121, 70, 32, 5 and 3, respectively). However, HPeV were identified in Senegal, Guinea and Mauritania (n = 10, 11 and 2, respectively). EVA71 and HRV were detected in Senegal while EVD68 and CVA6 were identified in Senegal and Guinea.

EchoV were also identified in all districts of the following countries: Guinea, Guinea Bissau and Gambia. However, they predominate in districts from Mauritania and Senegal with 97.4% (n=39) and 95.9% (n=140) respectively. The other types (HPeV, EVA71, EVD68, and CVA6), distribution varies according to the country. Indeed, HPeV were identified in 9 districts from Senegal (19.14%), 10 in Guinea (35.7%) and 2 in Mauritania (10%). In Senegal, EVA71 were identified in 2 districts (4.3%); EVD68 and CVA6 both in 1 district (2.12%). In Guinea, CVA6 and EVD68 were identified in 1 district (3.6%) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4: Proportion of the detected NPEV genotypes (A) and their geographical distribution by health districts that reported AFP cases in each country (B): Senegal (B1), Guinea (B2), Mauritania (B3), Guinea Bissau (B4) and Gambia (B5) during 2021.

Infection Profiles

Among isolates typed (n = 262), 97.8% were a single NPEV infection. Except for HRV, co-infections accounted for 4.5% (n = 12) of the positive isolates. The co-infection of HPeV and EchoV were more prevalent with 58.3% (n = 7), followed by EchoV and EVA71 with 16.6% (n = 2) (Table 2).

Table 2: Proportion of single infections and co-infections among NPEV-positive cases.

|

Single infections |

Co-infections |

||

|

EVD68 |

2 |

HPeV + EVD68 |

1 |

|

EVA71 |

2 |

EchoV + EVA71 |

2 |

|

CVA6 |

2 |

EchoV + HPeV + CVA6 |

1 |

|

EchoV |

231 |

EchoV + EVD68 |

1 |

|

HPeV |

23 |

HPeV + EchoV |

7 |

|

HRV |

2 |

|

|

|

Total (%) |

262 (97.8) |

Total (%) |

12 (4.5) |

Impact and Circulation Dynamics of Echov

As for AFP cases, the overall sex ratio was 1.2 with 4.2% missing data (n = 12). There was no difference in EchoV identification between male and females (122/97, p = 0.2995). The highest detection rate for EchoV involved children from 0 to 5 years-old (94.5%), when compared to the other age groups (p< 0.05) and the dynamic was similar in all countries (Table 3).

Table 3: Demographic characteristics in patients with EchoV in West Africa, 2021.

|

Features |

Senegal |

Guinea |

Mauritania |

Guinea Bissau |

Gambia |

Total |

P-Value |

|

(n =121) |

(n =70) |

(n =32) |

(n =5) |

(n =3) |

(n = 231) |

|

|

|

Gender % |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.2995 |

|

Female |

48 % (n = 58) |

30 % (n = 21) |

43.8 % (n = 14) |

60 % (n = 3) |

33.3 % (n = 1) |

42 % (n = 97) |

|

|

Male |

52 % (n = 63) |

57.1 % (n = 40) |

46.9 % (n = 15) |

40 % (n = 2) |

66.7 % (n = 2) |

52.8 % (n = 122) |

|

|

Missing |

0 |

12.9 % (n = 9) |

9.3 % (n = 3) |

0 |

0 |

5.2 % (n = 12) |

|

|

Age % |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.2x10-16 |

|

0-5 years |

96.7 % (n = 117) |

91.8 % (n = 56) |

89.6 % (n = 26) |

100 % (n = 5) |

100 % (n = 3) |

94.5 % (n = 207) |

|

|

5-10 years |

2.5 % (n = 3) |

8.2 % (n = 5) |

7 % (n = 2) |

0 |

0 |

4.6 % (n =10) |

|

|

10-15 years |

0.8% (n = 1) |

0 |

3.4 % (n = 1) |

0 |

0 |

0.9 % (n = 2) |

|

In addition, our data showed a seasonal distribution for EchoV circulating in West Africa. Two peaks were observed: one from February to July and another from August to November for those from Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Mauritania and Gambia. However, in Senegal they were mainly detected between March- July, and August-November (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Monthly distribution of EchoV isolates from AFP cases surveillance West Africa, 2021.

Molecular Diversity and Prevalence

Overall, the partial VP1 gene was successfully amplified from 47 out of the 54 EchoV isolates selected. Global amplicons from 7 EchoV isolates showed very weak signal insufficient for sequencing although they had a Ct value < 25 by qPCR targeting the 5’UTR. Sequencing data showed that these isolates belonged to 21 distinct EVB genotypes. The highest prevalence was recorded for EchoV with 38 sequences (80.8%). However, the generated sequences included other EVB species such as EVB75 and EVB84 with 8.5% (n = 4), CVB2 with 6.38% (n = 3) and CVA9 with 4.25% (n = 2). E33, E21, E3 and E7 were the most commonly identified genotypes (n = 6, 5, 4 and 4, respectively). Geographical distribution of the newly characterized EVB sequences showed that 6 (CVB2, E2, E12, E13, E18 and EVB84) were from Senegal, 7 from Guinea (CVA9, E1, E5, E6, E11, E20 and E30) and 1 from Guinea-Bissau (E25) (Table 4).

Table 4: Frequency of different EVB genotypes detected in stool specimens of AFP cases, based on partial VP1 gene sequences West Africa, 2021.

|

Types |

Senegal |

Guinea |

Mauritania |

Guinea Bissau |

Gambia |

Total |

|

(n = 20) |

(n = 15) |

(n = 7) |

(n = 3) |

(n = 2) |

(n = 47) |

|

|

Coxackievirus A9 |

|

2 |

|

|

|

2 |

|

Coxackievirus B2 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

Echovirus 1 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

1 |

|

Echovirus 2 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

Echovirus 3 |

|

1 |

2 |

|

1 |

4 |

|

Echovirus 5 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

1 |

|

Echovirus 6 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

1 |

|

Echovirus 7 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

4 |

|

Echovirus 11 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

1 |

|

Echovirus 12 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

Echovirus 13 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

Echovirus 18 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

Echovirus 19 |

1 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

3 |

|

Echovirus 20 |

|

2 |

|

|

|

2 |

|

Echovirus 21 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

5 |

|

Echovirus 25 |

|

|

|

1 |

|

1 |

|

Echovirus 31 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

2 |

|

Echovirus 30 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

1 |

|

Echovirus 33 |

3 |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

6 |

|

Enterovirus B75 (EVB75) |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

3 |

|

Enterovirus B84 (EVB84) |

1 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

Phylogenetic Analysis

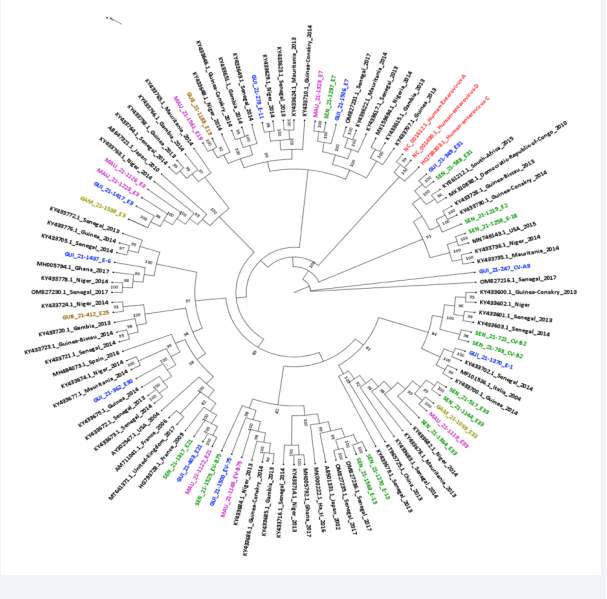

Phylogenetic inferences based on partial VP1 sequences were used to confirm the genotyping data. 34 out of the 47 VP1 sequences generated had a length of approximately 800bp and have been used for phylogenetic analyses. Multiple alignments of our dataset of 107 partial VP1 sequences including the 34 selected VP1 sequences and 73 sequences retrieved from GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) (accessed on 20 December 2022), was performed. The tree topology confirmed the genotyping data and showed that the newly characterized EVB sequences clustered with previous strains mainly from West Africa, and had nucleotide homology ranging from 90 to 100%, exhibiting a sub-regional clustering of enterovirus B species in West Africa (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Phylogenetic tree of EVB isolates identified in AFP cases surveillance programs West Africa, 2021 from 107 partial VP1 sequences (~800 bp) including sequences available from GenBank (black), 3 reference sequences belonging to the 3 human enterovirus species (red), 13 from Senegal (green), 10 from Guinea (blue), 7 from Mauritania (pink), 2 from Guinea Bissau (Brown) and 2 from Gambia (yellow). Bootstrap values ≥80 are shown on the tree that was rooted on midpoints

DISCUSSION

Beside polioviruses, some other viruses such as West Nile, Epstein-Barr, and NPEV may be responsible for AFP [32-34]. Therefore, surveillance of AFP cases is an essential strategy for better understanding the current molecular epidemiology of NPEV. Herein, we report on a one-year surveillance of NPEV in AFP cases for better understanding of their prevalence and the current molecular diversity in West Africa.

Our data showed that NPEV accounted for approximately 17.7% (417/2361) of total AFP cases reported in West Africa in 2021. This number is consistent with previous isolation rates reported for NPEV in most of the tropical countries (around 10%) [16]. However, higher detection rates have been previously reported in Nigeria and Congo (around 85%) [35,36]. These differences in isolation rates could be related not only to the use of different technical approaches, but also to differences in the overall incidence of these viruses and the population size in these countries. The highest prevalence of NPEV recorded in 0-5 years-old children exhibits the impact of enterovirus infections in this vulnerable age group as previously reported [37]. This age group could be prioritized as Target Population Profile (TPP) for future NPEV’s vaccine implementation. In addition, the temporal distribution of NPEV isolates observed in our study is consistent with those previously reported in West Africa [16,17]. The molecular screening with differential assays revealed also the presence of HPeV and HRV that accounted for 8.6% and 0.75%, respectively. The recorded prevalence found for these viruses in our study could be probably higher if we used clinical specimens such as clarified stool suspensions. HPeV and HRV are known for poor adaptation to cell culture systems and not all types replicate in the cell lines routinely used for EV isolation [38,39]. EVA71, CVA6 and EVD68 were also identified in our study with sporadic cases. These sporadic detections over 12 months confirmed the epidemic natural fitness and non-continuous pattern for these NPEV.

Interestingly, sequencing of the VP1 gene found that the primers used for detection of EchoV are not specific and amplified a large panel of EVB species. Therefore, there is a need to update the existing molecular assays according to the current molecular epidemiology to allow specific detection of the circulating EchoV and avoid primers erosion due to the large genetic diversity of NPEV [40].

The results of our research indicate the clear leadership of EVB as the etiological agents of AFP in West Africa. The high prevalence observed in our study for the EVB species is consistent with data previously reported from Africa [16,17]. However, more longitudinal studies focusing on the geographical and temporal dynamics of NPEV in Africa, including more countries, could be promoted in the future [41]. The large genetic diversity of EVB noted in our study was similar to previous data reported from AFP cases in West Africa (n = 27) [16] and highlighted a high prevalence of EchoV, which corroborated also previous data from Ghana, Nigeria, and Eastern China [42-44]. Echoviruses have been previously identified in 50% of central nervous system infections due to EV and described as the major EV type associated with cases of AM [7,45]. The most prevalent types identified in our study (E3, E33, E6, E7, E11 and E18), have been also previously associated with AFP, AM and HFMD in Africa, South America, Asia and Europe [16,46-48] while the E21 type was previously described in cases of AFP, meningitis, acute gastroenteritis and fulminant hepatitis [49].

Between 2001 and 2002, the E13 type emerged in the United States and Japan, and spread causing many epidemics of acute meningitis, worldwide. It has often been reported as a cause of childhood neurological diseases such as AFP and acute meningitis [50]. Through the AFP surveillance, E13 was also found to be the predominant NPEV in India and China [51,52] and among the most prevalent types in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic and south-west India [53]. Similarly, the E30 type is one of the most frequent genotypes associated with meningitis [54,55], causing multiple outbreaks with severe cases, worldwide [56]. However, The prevalence of E30 (2,12%) found in our study was slightly lower compared to data previously detected in west Africa [16], although sero-epidemiological studies previously reported high rates of E30 sero-positivity in younger age groups [57]. More studies could be important to determine environmental factors driving the low prevalence of E30 in AFP cases, particularly in West Africa. In addition, the circulation dynamics of less prevalent EVB species such as EVB84, E5, E12 and E20 and genetically distant genotypes such as E18 and E21 that clustered within sequences from USA and France, respectively, could be also monitored. Continuous surveillance of EVB-associated AFP in West Africa could help to understand patterns within the evolution of the epidemic process as well as other forms of enteroviral infection. Although considerable efforts have been made to develop EVA71-based vaccines [58- 60], EVB such as EchoV species could be also proposed as primary targets for vaccine development.

The VP1 gene analysis conducted in our study highlighted the ability of NPEV to spread over large geographical areas and exhibited the importance to pay more attention to the molecular epidemiology of NPEV worldwide and continue their surveillance in the context of various infections such as neurological diseases. It could be then important to set-up genomic surveillance of NPEV in more countries to better estimate their incidence and economic burden in Africa.

An active epidemiological and virological surveillance will play a key role in analysing the long-term incidence of AFP and other EV infections, along with an assessment of the influence of associated risk factors, systematic monitoring of the spread of new virus variants and the main causes of outbreak emergence. It will also provide the public health authorities with reliable data about the real epidemic potential of NPEV in order to readapt the existing local strategies for timely and appropriate preventive measures. Since poliomyelitis is being eradicated, the use of a testing approach combining cell isolation and systematic NPEV sequencing methods could guide clinicians for the appropriate management of patients.

CONCLUSION

Our study is to date, one of the largest that assessed the molecular epidemiology of NPEV in West Africa. It firstly highlighted that specific assays must be continuously monitored and updated, secondly the large genetic diversity of NPEV and added new insights on the high prevalence of EVB in AFP cases identified among young West African children. Information on the genetic diversity of NPEV in West Africa where sequencing data are still scarce, will contribute to better understanding their molecular epidemiology and provide an added value about the importance of these viral etiologies in the AFP syndrome. Our data are also noteworthy by the identification of rarely reported echovirus strains (E1, E3, and E20) and point out the urgent need to establish an effective NPEV surveillance system in Africa and implement appropriate public health prevention and control measures for significant reduction of AFP cases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all the staff of the virology department for their support, particularly the team of the Inter-country reference center for poliomyelitis.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Institutional Review Board Statement Not applicable. As part of the GPEI, our study did not directly involve humans or animals, but included cell culture isolates from AFP cases and Environmental Surveillance (ES) collected as part of routine surveillance activities for polio in Senegal, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, The Gambia and Mauritania for public health purposes. Protocols have been approved by WHO and the national ethical committee at the Ministries of Health. Clear oral consent was obtained from all patients or their parents or relatives.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceived the study: M.F; mobilized funding: O.F, A.AS, J.K, O.D; performed the experiment: N.N, F.D.T, O.K, K.L.D ; analyzed and interpreted the data: N.N, F.D.T, M.F; wrote the manuscript: N.N, F.D.T, M.F ; provided materials: H.N.D, M.L.D, S.B, G.C, L.D.E,O.JJ, S.F, B.D, A.D1 (Aliou Diallo); revised and accepted the final version of the manuscript: N.N, F.D.T, H.N.D, M.L.D, S.B, G.C, L.D.E, O.JJ, S.F, B.D, A.D1 (Aliou Diallo), A.D2 (Annick Dosseh), J.K, O.D, O.K, K.L.D, N.D, O.F, A.AS, M.F; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Noor A, Krilov LR. Enterovirus infections. Pediatr Rev. 2016; 37: 505-515.

- Tang JW, Holmes CW. Acute and chronic disease caused by enteroviruses. Virulence. 2017; 8: 1062-1065. doi: 10.1080/ 21505594.2017.1308620. Epub 2017 Mar 31. PMID: 28362547; PMCID: PMC5711444.

- Tapparel C, Siegrist F, Petty TJ, Kaiser L. Picornavirus and enterovirus diversity with associated human diseases. Infect Genet Evol. 2013; 14: 282-293. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.10.016. Epub 2012 Nov 29. PMID: 23201849.

- Classification and nomenclature of viruses. Fourth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Intervirology. 1982; 17: 1-199. doi: 10.1159/000149278. PMID: 6811498.

- Stanway G. Molecular Biology and Classification of Enteroviruses. In: Taylor K, Hyöty H, Toniolo A, Zuckerman AJ, eds. Diabetes and Viruses. Springer New York; 2013: 109-115.

- Brouwer L, Moreni G, Wolthers KC, Pajkrt D. Worldwide Prevalence and Genotype Distribution of Enteroviruses. Viruses. 2021; 13: 434. doi: 10.3390/v13030434. PMID: 33800518; PMCID: PMC7999254.

- Tapparel C, Siegrist F, Petty TJ, Kaiser L. Picornavirus and enterovirus diversity with associated human diseases. Infect Genet Evol. 2013; 14: 282-293. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.10.016. Epub 2012 Nov 29. PMID: 23201849.

- Lee BE, Davies HD. Aseptic meningitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007; 20:272-277.

- Antona D, Kossorotoff M, Schuffenecker I, Mirand A, Leruez-Ville M, Bassi C, et al. Severe paediatric conditions linked with EV-A71 and EV-D68, France, May to October 2016. Euro Surveill. 2016; 21: 30402. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.46.30402. PMID: 27918268; PMCID: PMC5144948.

- Esneau C, Duff AC, Bartlett NW. Understanding Rhinovirus Circulation and Impact on Illness. Viruses. 2022; 14: 141. doi: 10.3390/ v14010141. PMID: 35062345; PMCID: PMC8778310.

- van Hinsbergh TMT, Elbers RG, Hans Ket JCF, van Furth AM, Obihara CC. Neurological and neurodevelopmental outcomes after human parechovirus CNS infection in neonates and young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020; 4: 592-605. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30181-4. Epub 2020 Jul 22. PMID: 32710840.

- Britton PN, Jones CA, Macartney K, Cheng AC. Parechovirus: an important emerging infection in young infants. Med J Aust. 2018; 208: 365-369. doi: 10.5694/mja18.00149. PMID: 29716506.

- Louten J. Detection and diagnosis of viral infections. Essent Hum Virol. Published online 2016:111-132.

- Nijhuis M, van Maarseveen N, Schuurman R, Verkuijlen S, de Vos M, Hendriksen K, et al. Rapid and sensitive routine detection of all members of the genus enterovirus in different clinical specimens by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2002; 40: 3666-3670. doi: 10.1128/ JCM.40.10.3666-3670.2002. PMID: 12354863; PMCID: PMC130891.

- Oberste MS, Maher K, Kilpatrick DR, Pallansch MA. Molecular evolution of the human enteroviruses: correlation of serotype with VP1 sequence and application to picornavirus classification. J Virol. 1999; 73: 1941-1948. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.3.1941-1948.1999. PMID: 9971773; PMCID: PMC104435.

- Fernandez-Garcia MD, Kebe O, Fall AD, Ndiaye K. Identification and molecular characterization of non-polio enteroviruses from children with acute flaccid paralysis in West Africa, 2013-2014. Sci Rep. 2017; 7: 3808. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03835-1. PMID: 28630462; PMCID: PMC5476622.

- NdiayeN,Fall A, Kébé O, Kiory D,DiaH,Fall M, et al. National Surveillance of Acute Flaccid Paralysis Cases in Senegal during 2017 Uncovers the Circulation of Enterovirus Species A, B and C. Microorganisms. 2022; 10: 1296. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10071296. PMID: 35889015; PMCID: PMC9319795.

- Sadeuh-Mba SA, Bessaud M, Massenet D, Joffret ML, Endegue MC, Njouom R, et al. High frequency and diversity of species C enteroviruses in Cameroon and neighboring countries. J Clin Microbiol. 2013; 51: 759-770. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02119-12. Epub 2012 Dec 19. PMID: 23254123; PMCID: PMC3592076.

- Majumdar M, Klapsa D, Wilton T, Bujaki E, Fernandez-Garcia MD, Faleye TOC, et al. High Diversity of Human Non-Polio Enterovirus Serotypes Identified in Contaminated Water in Nigeria. Viruses. 2021; 13: 249. doi: 10.3390/v13020249. PMID: 33562806; PMCID: PMC7914538.

- Organization WH. Polio Laboratory Manual. World Health Organization. 2004.

- Fujimoto T, Izumi H, Okabe N, Enomoto M, Konagaya M, Chikahira M, et al. Usefulness of real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of echovirus aseptic meningitis using cerebrospinal fluid. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2009; 62: 455-457. PMID: 19934538.

- Puenpa J, Suwannakarn K, Chansaenroj J, Vongpunsawad S, Poovorawan Y. Development of single-step multiplex real-time RT- PCR assays for rapid diagnosis of enterovirus 71, coxsackievirus A6, and A16 in patients with hand, foot, and mouth disease. J Virol Methods. 2017; 248: 92-99. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2017.06.013. Epub 2017 Jun 27. PMID: 28662914.

- Zhang L, Wang X, Zhang Y, Gong L, Mao H, Feng C, et al. Rapid and sensitive identification of RNA from the emerging pathogen, coxsackievirus A6. Virol J. 2012; 9: 298. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9- 298. PMID: 23194501; PMCID: PMC3566960.

- Cui A, Xu C, Tan X, Zhang Y, Zhu Z, Mao N, et al. The development and application of the two real-time RT-PCR assays to detect the pathogen of HFMD. PLoS One. 2013; 8: e61451. doi: 10.1371/journal. pone.0061451. PMID: 23637836; PMCID: PMC3630163.

- Piralla A, Girello A, Premoli M, Baldanti F. A new real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay for detection of human enterovirus 68 in respiratory samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2015; 53: 1725-1726. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03691-14. Epub 2015 Feb 18. PMID: 25694533; PMCID: PMC4400749.

- Feng ZS, Zhao L, Wang J, Qiu FZ, Zhao MC, Wang L, et al. A multiplex one-tube nested real time RT-PCR assay for simultaneous detection of respiratory syncytial virus, human rhinovirus and human metapneumovirus. Virol J. 2018; 15: 167. doi: 10.1186/s12985-018- 1061-0. PMID: 30376870; PMCID: PMC6208169.

- Selvaraju SB, Nix WA, Oberste MS, Selvarangan R. Optimization of a combined human parechovirus-enterovirus real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay and evaluation of a new parechovirus 3-specific assay for cerebrospinal fluid specimen testing. J Clin Microbiol. 2013; 51: 452-458. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01982-12. Epub 2012 Nov 21. PMID: 23175256; PMCID: PMC3553926.

- Nix WA, Oberste MS, Pallansch MA. Sensitive, seminested PCR amplification of VP1 sequences for direct identification of all enterovirus serotypes from original clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2006; 44: 2698-2704. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00542-06. PMID: 16891480; PMCID: PMC1594621.

- Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series. 1999; 41: 95-98.

- Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015; 32: 268-274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/ msu300. Epub 2014 Nov 3. PMID: 25371430; PMCID: PMC4271533.

- Rambaut A. FigTree, a graphical viewer of phylogenetic trees (tree. bio. ed. ac. 691 uk/software/figtree). Inst Evol Biol Univ Edinb. 2014; 1: 2.

- Mehrabi Z, Shahmahmoodi S, Eshraghian MR, Tabatabaie H, Yousefi M, Mollaie Y, et al. Molecular detection of different types of non- polio enteroviruses in acute flaccid paralysis cases and healthy children, a pilot study. J Clin Virol. 2011; 50: 181-182. doi: 10.1016/j. jcv.2010.10.006. Epub 2010 Nov 3. PMID: 21051279.

- Saad M, Youssef S, Kirschke D, Shubair M, Haddadin D, Myers J, et al. Acute flaccid paralysis: the spectrum of a newly recognized complication of West Nile virus infection. J Infect. 2005; 51: 120-127. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.10.005. Epub 2004 Nov 6. PMID: 16038762.

- Wong M, Connolly AM, Noetzel MJ. Poliomyelitis-like syndrome associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. Pediatr Neurol. 1999; 20: 235-237. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(98)00142-8. PMID: 10207935.

- Faleye TOC, Adewumi MO, Japhet MO, David OM, Oluyege AO, Adeniji JA, et al. Non-polio enteroviruses in faeces of children diagnosed with acute flaccid paralysis in Nigeria. Virol J. 2017; 14: 175. doi: 10.1186/ s12985-017-0846-x. PMID: 28899411; PMCID: PMC5596853.

- Junttila N, Lévêque N, Kabue JP, Cartet G, Mushiya F, Muyembe- Tamfum JJ, et al. New enteroviruses, EV-93 and EV-94, associated with acute flaccid paralysis in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. J Med Virol. 2007; 79: 393-400. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20825. PMID: 17311342.

- Tseng JJ, Lin CH, Lin MC. Long-Term Outcomes of Pediatric Enterovirus Infection in Taiwan: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Front Pediatr. 2020; 8: 285. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00285. PMID: 32596191; PMCID: PMC7303813.

- Benschop K, Minnaar R, Koen G, van Eijk H, Dijkman K, Westerhuis B, et al. Detection of human enterovirus and human parechovirus (HPeV) genotypes from clinical stool samples: polymerase chain reaction and direct molecular typing, culture characteristics, and serotyping. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010; 68: 166-173. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.05.016. PMID: 20846590.

- Lee WM, Chen Y, Wang W, Mosser A. Growth of human rhinovirus in H1-HeLa cell suspension culture and purification of virions. Methods Mol Biol. 2015; 1221: 49-61. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1571-2_5. PMID: 25261306.

- Ikuse T, Aizawa Y, Takihara H, Okuda S, Watanabe K, Saitoh A. Development of Novel PCR Assays for Improved Detection of Enterovirus D68. J Clin Microbiol. 2021; 59: e0115121. doi: 10.1128/ JCM.01151-21. Epub 2021 Aug 25. PMID: 34432489; PMCID: PMC8525583.

- Pons-Salort M, Parker EP, Grassly NC. The epidemiology of non-polio enteroviruses: recent advances and outstanding questions. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2015; 28: 479-487. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000187. PMID: 26203854; PMCID: PMC6624138.

- Oyero OG, Adu FD. Non-polio enteroviruses serotypes circulating in Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2010; 39: 201-208. PMID: 22416664.

- Tao Z, Wang H, Liu Y, Li Y, Jiang P, Liu G, et al. Non-polio enteroviruses from acute flaccid paralysis surveillance in Shandong Province, China, 1988-2013. Sci Rep. 2014; 4: 6167. doi: 10.1038/srep06167. PMID: 25145609; PMCID: PMC4141246.

- Odoom JK, Obodai E, Barnor JS, Ashun M, Arthur-Quarm J, Osei-Kwasi M. Human Enteroviruses isolated during acute flaccid paralysis surveillance in Ghana: implications for the post eradication era. Pan Afr Med J. 2012; 12: 74. Epub 2012 Jul 16. PMID: 23077695; PMCID: PMC3473960.

- Mirand A, Archimbaud C, Henquell C, Michel Y, Chambon M, Peigue- Lafeuille H, et al. Prospective identification of HEV-B enteroviruses during the 2005 outbreak. J Med Virol. 2006; 78: 1624-1634. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20747. PMID: 17063526.

- Cabrerizo M, Echevarria JE, González I, de Miguel T, Trallero G. Molecular epidemiological study of HEV-B enteroviruses involved in the increase in meningitis cases occurred in Spain during 2006. J Med Virol. 2008; 80: 1018-1024. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21197. PMID: 18428125.

- Chen X, Li J, Guo J, Xu W, Sun S, Xie Z. An outbreak of echovirus 18 encephalitis/meningitis in children in Hebei Province, China, 2015. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2017; 6: e54. doi: 10.1038/emi.2017.39. PMID: 28634356; PMCID: PMC5584482.

- Wang W, Fan H, Zhou S, Li S, Nigedeli A, Zhang Y, et al. Molecular Characteristics and Genetic Evolution of Echovirus 33 in Mainland of China. Pathogens. 2022; 11: 1379. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11111379. PMID: 36422630; PMCID: PMC9697921.

- Liu H, Cong S, Xu D, Lin K, Huang X, Sun H, et al. Characterization of a novel echovirus 21 strain isolated from a healthy child in China in 2013. Arch Virol. 2020; 165: 757-760. doi: 10.1007/s00705-019- 04506-4. Epub 2020 Jan 7. PMID: 31912293.

- Mullins JA, Khetsuriani N, Nix WA, Oberste MS, LaMonte A, Kilpatrick DR, et al. Emergence of echovirus type 13 as a prominent enterovirus. Clin Infect Dis. 2004; 38: 70-77. doi: 10.1086/380462. Epub 2003 Dec 8. PMID: 14679450.

- Maan HS, Chowdhary R, Shakya AK, Dhole TN. Genetic variants of echovirus 13, northern India, 2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013; 19: 293-296. doi: 10.3201/eid1902.111832. PMID: 23343581; PMCID: PMC3559031.

- Bingjun T, Yoshida H, Yan W, Lin L, Tsuji T, Shimizu H, et al. Molecular typing and epidemiology of non-polio enteroviruses isolated from Yunnan Province, the People’s Republic of China. J Med Virol. 2008; 80: 670-679. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21122. PMID: 18297723.

- Bessaud M, Pillet S, Ibrahim W, Joffret ML, Pozzetto B, Delpeyroux F, et al. Molecular characterization of human enteroviruses in the Central African Republic: uncovering wide diversity and identification of a new human enterovirus A71 genogroup. J Clin Microbiol. 2012; 50: 1650-1658. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06657-11. Epub 2012 Feb 15. PMID: 22337981; PMCID: PMC3347117.

- Suresh S, Rawlinson WD, Andrews PI, Stelzer-Braid S. Global epidemiology of nonpolio enteroviruses causing severe neurological complications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. 2020; 30: e2082. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2082. Epub 2019 Oct 6. PMID: 31588651.

- Farshadpour F, Taherkhani R. Molecular epidemiology of enteroviruses and predominance of echovirus 30 in an Iranian population with aseptic meningitis. J Neurovirol. 2021; 27: 444- 451. doi: 10.1007/s13365-021-00973-1. Epub 2021 Mar 31. PMID: 33788142.

- Broberg EK, Simone B, Jansa J, EU/EEA Member State contributors. Upsurge in echovirus 30 detections in five EU/EEA countries, April to September, 2018. Euro Surveill. 2018; 23: 1800537. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.44.1800537. PMID: 30401013; PMCID: PMC6337069.

- Österback R, Kalliokoski T, Lähdesmäki T, Peltola V, Ruuskanen O, Waris M. Echovirus 30 meningitis epidemic followed by an outbreak- specific RT-qPCR. J Clin Virol. 2015; 69: 7-11. doi: 10.1016/j. jcv.2015.05.012. Epub 2015 May 22. PMID: 26209368.

- Zhang Z, Dong Z, Li J, Carr MJ, Zhuang D, Wang J, et al. Protective Efficacies of Formaldehyde-Inactivated Whole-Virus Vaccine and Antivirals in a Murine Model of Coxsackievirus A10 Infection. J Virol. 2017; 91: e00333-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00333-17. PMID: 28424287; PMCID: PMC5469256.

- He X, Zhang M, Zhao C, Zheng P, Zhang X, Xu J. From Monovalent to Multivalent Vaccines, the Exploration for Potential Preventive Strategies against Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease (HFMD). Virol Sin. 2021; 36: 167-175. doi: 10.1007/s12250-020-00294-3. Epub 2020 Sep 30. PMID: 32997323; PMCID: PMC7525078.

- Zhang W, Dai W, Zhang C, Zhou Y, Xiong P, Wang S, et al. A virus-like particle-based tetravalent vaccine for hand, foot, and mouth disease elicits broad and balanced protective immunity. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2018; 7: 94. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0094-1. PMID: 29777102; PMCID: PMC5959873.