Vancomycin Stewardship: Focus on the First Dose

- 1. Departments of Infection Prevention, Stamford Health, Stamford, Connecticut, USA

- 2. Departments of Pharmacy, Stamford Health, Stamford, Connecticut, USA

- 3. Departments of Infectious Diseases, Stamford Health, Stamford, Connecticut, USA

- 4. Division of Infectious Diseases, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, USA

Abstract

Background: It is widely appreciated that vancomycin use is excessive. A drug use evaluation of intravenous vancomycin orders at our hospital showed that 48% were inappropriate. This finding was surprising because our stewardship program required Infectious Disease (ID) approval for all vancomycin orders, although it allowed an emergency dose prior to approval.

Methods: After a comprehensive, hospital-wide educational program, all vancomycin orders were required to have ID pre-approval without exception.

Two months after the new pre-approval process began, vancomycin orders were again evaluated for appropriateness.

Results: After the intervention, there was a decrease in inappropriate prescribing from 48% to 22% of patients (p < 0.001), and a decrease in inappropriate days-on-therapy from 37% to 18% (p < 0.001). These improvements were due mainly to decreased prescribing of first dose, empiric use, in the Emergency Department (ED). No change was seen in clinical diagnosis, correctness of weight-based dosing, patient outcomes, or the rationale for vancomycin use. Common misconceptions amongst prescribers contributed to the overprescribing of vancomycin: (1) routinely adding vancomycin for empiric treatment of sepsis without risk factors for MRSA; (2) the false perception that vancomycin is necessary to “cover” various species of streptococci; (3) the need to treat a single positive blood culture growing coagulase-negative staphylococci; and (4) imprecision in assigning a diagnosis of “penicillin allergy”.

Conclusions: Eliminating the provision for single dose vancomycin administration without ID pre-approval resulted in more appropriate vancomycin prescribing, particularly in the ED. Education to improve prescribing habits and dispel misconceptions about the empiric role of vancomycin was enabled by the pre-approval process.

KEYWORDS

- Vancomycin Utilization; Antibiotic Stewardship; Antibiotic Pre-Approval; Inappropriate Use of Antibiotics

CITATION

Zolla B, Michalowska-Suterska M, Shah AK, Parry MF (2024) Vancomycin Stewardship: Focus on the First Dose. Clin Res Infect Dis 8(2): 1069.

ABBREVIATIONS

ID: Infectious Diseases; ED: Emergency Department; MRSA: Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus; MRSE: Methicillin- Resistant Staphylococcus Epidermidis; SSTI: Skin and Soft Tissue Infection; EMR: Electronic Medical Record; DUE: Drug Use Evaluation; PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; DOT: Days on Therapy

BACKGROUND

Vancomycin is often reflexively prescribed for the treatment of sepsis, usually in combination with other agents, due to the perception that it will cover all gram-positive flora without exception. In addition, there is a belief that Methicillin-Resistant Staphyloccus Aureus (MRSA) is likely to be the offending pathogen in a wide variety of skin and Soft Tissue Infections (SSTI) and requires empiric treatment with vancomycin. These perceptions have led to the inappropriate prescribing of vancomycin in up to 70% of cases [1-6]. Furthermore, overprescribing vancomycin has led to the emergence of resistance in enterococci, threatens its role for the treatment of staphylococcal infections, and contributes to cases of nephrotoxicity in patients.

A review of 100 consecutive patients receiving therapeutic intravenous vancomycin at Stamford Hospital showed that 48% of orders were inappropriate, using previously published criteria [1-8]. 50% of these were single-dose orders and 64% of these were ordered by Emergency Department (ED) physicians. These findings were surprising given our active antimicrobial stewardship program that required Infectious Disease service (ID) approval of vancomycin, but the restrictions were poorly enforced and traditionally allowed an initial dose before obtaining approval. Therefore, we hoped to improve the appropriateness of vancomycin utilization by revising our stewardship intervention plan.

METHODS

Stamford Hospital is a 330-bed independent community teaching hospital in southwestern Connecticut. Most inpatient orders are written by an employed hospitalist service (medical, family practice and pediatric services) or resident team (medicine, family practice, surgery or obstetrics/gynecology). Emergency services are provided onsite by a contracted emergency medicine group. Our antimicrobial stewardship program evolved over the preceding 15 years and relied heavily on a limited formulary with restricted agents requiring approval by members of the ID service, supplemented by prepopulated orders and published practice guidelines. The inpatient ID practice was comprised of four board certified physicians; there were no fellows or residents involved. Historically, an initial dose or two of restricted antibiotic was usually allowed before obtaining ID service approval. Unless a formal ID consult was obtained as part of the approval process, patients on restricted agents were not routinely followed after initial approval was granted and there was no formal de- escalation policy.

From September to October 2022, 100 consecutive patients receiving therapeutic vancomycin were analyzed by retrospective Electronic Medical Record (EMR) review as part of our routine stewardship Drug Use Evaluation process (DUE). Patients were selected from the pharmacy administration records, having received at least one dose of intravenous vancomycin. Patients receiving prophylactic vancomycin use were excluded. Practitioner decision making was assessed by detailed review of progress notes in the EMR. “Appropriateness” of vancomycin prescribing was determined according to four criteria, based on prior guidelines [1-8]: (1) proven MRSA or MRSE infection; (2) suspected serious systemic infection with a positive MRSA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) screening test or past history of documented MRSA infection; (3) Seriously ill patient with infection where MRSA or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis was a reasonably suspected pathogen and a risk factor was present (diabetes mellitus, intravenous drug use, living in congregate housing, homeless, post-surgery infection); (4) patient with β-lactam allergy with proven or suspected infection due to vancomycin susceptible gram-positive pathogen. In options 2 and 3, “appropriateness” included an order to de- escalate within 48 hours if culture information was available. Only inpatient treatment was assessed (treatment started in the ED was included). Alternate MRSA treatment options (e.g., daptomycin, ceftaroline or oral therapies) were not considered in determining vancomycin appropriateness and a history of β-lactam allergy was accepted at face value, realizing that many of these patients were probably not truly allergic.

After analyzing the initial 100 consecutive cases, in December 2022 new stewardship interventions were implemented. Providers underwent formal education on appropriate vancomycin prescribing and all vancomycin orders required ID approval before prescribing (single doses without pre-approval were permitted only between 11 pm. and 6 am). This plan was conceived based on the high prevalence of single-dose orders; it was felt that to focus on de-escalation would not achieve the intended goals. Approval to prescribe vancomycin was to be documented by the ID specialist in the progress notes or pharmacist in the medication administration record. Two months after implementation of the new stewardship initiative, from February to March 2023, a second 100 consecutive patients receiving intravenous vancomycin were reviewed to assess the impact of the change.

Medical records were independently reviewed by an infection preventionist and a senior board-certified infectious disease physician not concurrently involved in any of the inpatient vancomycin prescribing or vancomycin approval activity. Prescribing data and provider narratives were retrieved from the EMR (Meditech®, Sunnyvale, Ca) and internal IT programmers who created reports (Tableau® Software, Seattle, WA) for pharmacy medication administration and Days-On-Therapy (DOT). In-hospital mortality was recorded without regard to attribution and 30-day readmission rates were calculated according to CMS guidelines, then analyzed as to cause (non- infectious cause for readmission, infectious disease cause for readmission, and vancomycin-susceptible infectious disease cause for readmission). The DUE used an interrupted time series methodology, 2x2 contingency tables (Graphpad® Software, La Jolla, CA), and 2-tailed Fisher’s exact test for statistical significance. P-values were judged significant at a P value < 0.05.

RESULTS

Therapeutic vancomycin treatment in the baseline group of 100 patients totaled 252 DOT. Median duration of treatment was 2 days, range 1-12 days. Principal diagnoses were suspected skin and soft tissue infection (34), lower respiratory tract infection (14), bone and joint infection (11), urinary tract infection (9), primary bacteremia, including endocarditis (7) and other (13). 30 patients were clinically septic and 12 had no infectious diagnosis listed. 66 patients had a formal infectious diseases consultation. The initial vancomycin dose was judged appropriate in 64% (15- 25 mg/kg) and suboptimal in 32% (< 15 mg/kg).

Baseline assessment of the pre-intervention group showed that 48% (48/100) of vancomycin orders were inappropriate. 50% of these were single dose orders, and of these, 64% were ordered by ED physicians. 7 of 52 patients deemed initially appropriate failed to de-escalate despite available culture results. As a result, a total of 37% of DOT (94/252 days) were deemed inappropriate. Vancomycin use in the 52 patients judged clinically appropriate was justified according to the criteria enumerated above and shown in (Table 1).

Table 1: Clinical criteria for appropriate vancomycin use by clinicians before and after the stewardship intervention.

|

Indication for vancomycin use |

Baseline (%) |

After intervention (%) |

|

Proven MRSA or MRSE infection |

23 |

22 |

|

Suspected infection with + history MRSA |

12 |

13 |

|

Suspected infection with MRSA risk factor |

48 |

51 |

|

Beta lactam allergy |

17 |

14 |

After the stewardship intervention, vancomycin administration in the 100 patients totaled 306 DOT (Table 2).

Table 2: Outcome of stewardship intervention on appropriateness of vancomycin prescribing.

|

Vancomycin Drug Utilization Evaluation |

|||

|

Measure: Days on Therapy |

Before Intervention (n = 252) |

After Intervention (n = 306) |

p -value |

|

Days on Therapy Appropriate |

158 (63%) |

252 (82%) |

p < 0.001 |

|

Days on Therapy Inappropriate |

94 (37%) |

54 (18%) |

|

|

Measure: Patients |

Before Intervention (n = 100) |

After Intervention (n = 100) |

p -value |

|

Patients who received Appropriate treatment |

52 (52%) |

78 (78%) |

p < 0.001 |

|

Patients who received Inappropriate treatment |

48 (48%) |

22 (22%) |

|

|

Measure: ID Approval |

Before Intervention (n = 100) |

After Intervention (n = 100) |

p -value |

|

Vancomycin orders with ID consultation |

66 (66%) |

81 (81%) |

p = 0.02 |

|

Vancomycin orders without ID consultation |

34 (34%) |

19 (19%) |

|

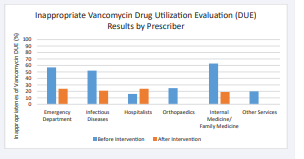

Median duration of treatment was again 2 days, range 1-28 days. Inappropriate DOT decreased from 37% (94/252 days) to 18% (54 of 306 days) (p < 0.001). Similarly, there was a decrease in the proportion of inappropriate prescribing from 48% to 22% of patients (p < 0.001). All clinical services reduced inappropriate vancomycin use except for the hospitalists (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Inappropriateness of vancomycin prescribing according to clinical service, before and after the stewardship intervention.

These improvements were due mainly to decreased prescribing of single doses in the ED which resulted in a slight increase in prescribing by the hospitalist service. 81% of patients had a formal infectious diseases consultation, increased from 66% (p < 0.02). The pre-approval process was documented by pharmacists in 82% of patients where vancomycin was prescribed after the intervention.

No change was seen in the reasons for vancomycin use, patients’ clinical diagnosis, correctness of weight-based dosing, or patient outcomes. Principal diagnoses did not differ significantly from the baseline group: suspected skin and soft tissue infection (35), lower respiratory tract infection (10), bone and joint infection (12), urinary tract infection (7), primary bacteremia, including endocarditis (20), other (12) and no infection (4). The appropriateness of vancomycin dosing was not addressed by the stewardship intervention and was unchanged from baseline (30% of dosing was suboptimal at < 15 mg/kg). Patient outcomes were not significantly different before and after the change in stewardship program. Inpatient mortality (10% versus 7%), 30- day readmission (18% versus 13%), and 30-day readmission for infection that justified vancomycin treatment (5% versus 4%) were no different in the post-intervention group compared to the baseline group (all P values > 0.5).

Practitioner misconceptions were apparent from our chart reviews both before and after the stewardship intervention. Themes were grouped as follows: (1) overestimating the prevalence of MRSA; (2) routinely adding vancomycin for empiric treatment of sepsis without risk factors for MRSA; (3) the false perception that vancomycin is necessary to “cover” various species of streptococci; (4) the need to use vancomycin for coverage of single blood cultures growing coagulase-negative staphylococci; and (5) imprecision in assigning a diagnosis of “penicillinallergy”. Due to the small number of total cases and the imprecision of practitioner documentation, the themes could not be easily quantified

DISCUSSION

We evaluated vancomycin use at Stamford Hospital as an antibiotic stewardship initiative. We found widespread misconceptions about the role of vancomycin and deemed its use inappropriate 48% of the time based on previously established criteria [1-8]. These percentages are compatible with findings published elsewhere [1-9]. Since the first multi-society consensus guideline for therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin for serious MRSA infections was published in 2009, most vancomycin stewardship initiatives have focused on the appropriateness of vancomycin levels, dosing algorithms and pharmacokinetics [10] rather than the decision to initiate vancomycin treatment. Even when stewardship initiatives have addressed the clinical decision to prescribe vancomycin, most of the focus has been on de-escalation rather than pre-emptive approval [2-11].

It was clear from analyzing the pre-intervention group at our hospital that most of the correctible excess vancomycin use was due to single dose therapy for presumed sepsis, often, but not exclusively, in the ED. De-escalation offered less of an opportunity. In fact, only 10 vancomycin DOT judged to be inappropriate (4.0%) could have been saved by intervening to de-escalate. Therefore, we elected to require pre-approval for all vancomycin doses. After the pre-approval process was implemented, we achieved a 54% reduction in inappropriate orders and 43% reduction in inappropriate DOT.

A concern raised by clinicians during implementation of the pre-approval process was that outcome gains made in the treatment of sepsis through the Surviving Sepsis Campaign [12] and compliance with CMS National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures [13] might be lost by delaying the antibiotic approval process. Clearly, the absence of available ID clinicians to discuss the case and grant antibiotic approval would have been problematic unless it was replaced by an electronic pre-approval process as has been done by some institutions [3-15]. In our hospital, the expectations of 24/7 ID consult availability were set prior to implementation of the process and has not been a problem. In fact, a 3-month report from our Sepsis Committee, monitoring the Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Bundle, found no cases of delayed antibiotic initiation after implementation of the pre-approval process. Neither was there a negative impact on in-hospital mortality or 30-day readmissions for relapsing infection.

Further improvements in vancomycin stewardship require ongoing physician education to dispel misconceptions about the role of vancomycin. Practitioner misconceptions were apparent from our chart reviews both before and after the stewardship intervention. Overestimating the prevalence of MRSA has been noted by others [16], fostering the routine addition of vancomycin for empiric treatment of sepsis without risk factors for MRSA. We also found that clinicians falsely perceived that vancomycin was necessary to “cover” all gram-positive flora including various species of streptococci. Blood, body fluid, or tissue cultures growing gram-positive cocci in chains was not considered an appropriate use of the drug; and if enterococcus was considered possible, re-education on the prevalence of vancomycin-resistant strains is important. Additionally, the use of vancomycin for coverage of single blood cultures growing coagulase-negative staphylococci constitutes “low-hanging fruit” for vancomycin disapproval. Finally, there remains imprecision in assigning a diagnosis of “penicillin allergy”. Better clarification of the type of allergy (as could be built into EMR documentation) would allow safe beta-lactam use in many such cases. This has been a useful stewardship tool, as shown by others [17,18].

This is a relatively small DUE in a single community teaching hospital and our results may be limited in scope. They may not be applicable to larger urban or tertiary care facilities. The assessment of “inappropriateness” of therapy in a retrospective chart review, furthermore, is often subjective despite our best attempts to preemptively categorize cases based on established criteria. Our relative abundance of ID clinicians (albeit no fellows) who were motivated to participate and educate (but not required to provide formal consultation) resulted in a prompt response for consultation and drug approval or disapproval. Such may not be the case in many other institutions and electronic solutions may be better options. Finally, we were not able in this short time frame to assess the impact of our vancomycin use reduction on the prevalence of vancomycin resistance or vancomycin toxicity.

CONCLUSION

Most vancomycin stewardship initiatives have focused on the appropriateness of vancomycin levels, dosing algorithms and pharmacokinetics [10] rather than the decision to initiate vancomycin treatment in the first place. We found little opportunity for vancomycin sue reduction by addressing de- escalation or better dosing algorithms. However, eliminating the provision for vancomycin administration without ID pre-approval resulted in much more appropriate vancomycin prescribing, particularly in the ED. Education to improve prescribing habits and dispel misconceptions about the empiric role of vancomycin was enabled by the pre-approval process.

DECLARATIONS

Ethics approval and consent to participate:

This project was designed as a drug use evaluation as part of our antibiotic stewardship and quality improvement program. It was conducted under institutional auspices and exempt from Institutional Review Board Approval. No protected health information is included in the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

Data accessed in this project were mined from the EMR and contain PHI. A limited dataset, redacted of PHI, can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors Contributions

The project was designed by AKS and MFP. The stewardship program was administered by AKS and MM. The data were extracted from the EMR and analyzed by BZ and MFP. The first draft was written by BZ and MFP with revisions by MM and AKS. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgement

We wish to acknowledge the many hours of uncompensated consultation provided by the infectious diseases clinicians, and the contributions of the antimicrobial stewardship team, the clinical pharmacists, infection preventionists and the microbiology laboratory.

REFERENCES

- Recommendations for preventing the spread of vancomycin resistance. Recommendations of the Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). MMWR Recomm Rep. 1995; 44: 1-13. PMID: 7565541.

- Shebli Atrash, Katherine T Lusardi, Juan Carlos Rico, Rajesh Banderudrappagari, Angela Pennisi, Belal Firwana, et al. A quality improvement project to decrease overuse of vancomycin in an inpatient hematology/oncology service. J Clinical Oncol. 2016; 34: 15_suppl.e18167. Doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.34.

- Anglim AM, Klym B, Byers KE, Scheld WM, Farr BM. Effect of a vancomycin restriction policy on ordering practices during an outbreak of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. Arch Intern Med. 1997; 157: 1132-1136. PMID: 9164379.

- Singer MV, Haft R, Barlam T, Aronson M, Shafer A, Sands KE. Vancomycin control measures at a tertiary-care hospital: impact of interventions on volume and patterns of use. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1998; 19: 248-253. doi: 10.1086/647803. PMID: 9605273.

- Thomas AR, Cieslak PR, Strausbaugh LJ, Fleming DW. Effectiveness of pharmacy policies designed to limit inappropriate vancomycin use: a population-based assessment. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002; 23: 683-688. doi: 10.1086/501994. PMID: 12452297.

- Kim NH, Koo HL, Choe PG, Cheon S, Kim M, Lee MJ, et al. Inappropriate continued empirical vancomycin use in a hospital with a high prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015; 59: 811-817. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04523-14. Epub 2014 Nov 17. Erratum in: Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015; 59: 2478. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00241-15. Choe, Pyeong Gyun [corrected to Choe, Pyoeng Gyun]; Kim, Moon Suk [corrected to Kim, Moonsuk]; Jung, Young Hee [corrected to Jung, Younghee]. PMID: 25403664; PMCID: PMC4335878.

- Drori-Zeides T, Raveh D, Schlesinger Y, Yinnon AM. Practical guidelines for vancomycin usage, with prospective drug-utilization evaluation. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000; 21: 45-47. doi: 10.1086/501697. PMID: 10656356.

- Cieslak PR, Strausbaugh LJ, Fleming DW, Ling JM. Vancomycin in Oregon: who’s using it and why. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999; 20: 557-560. doi: 10.1086/501669. PMID: 10466557.

- Roghmann MC, Perdue BE, Polish L. Vancomycin use in a hospital withvancomycin restriction. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999; 20: 60-63. doi: 10.1086/501548. PMID: 9927270.

- Rybak MJ, Le J, Lodise TP, Levine DP, Bradley JS, Liu C, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin for serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: A revised consensus guideline and review by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020; 77: 835-864. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/ zxaa036. PMID: 32191793.

- Heather Glassman, Arif Ismail, Stephanie W Smith, Jackson J Stewart, Cecilia Lau, Dima Kabbani, et al. Appropriateness of intravenous vancomycin in a Canadian acute care hospital. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022; 9: 1414.

- Society for Critical Care Medicine. https://www.sccm.org/SurvivingSepsisCampaign/Guidelines/Adult-Patient. Accessed 9/18/2023.

- CMS. Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting Program. https://www. cms.gov/medicare/quality/initiatives/hospital-quality-initiative/ inpatient-reporting-program. Accessed 9/26/23.

- Shojania KG, Yokoe D, Platt R, Fiskio J, Ma’luf N, Bates DW. Reducing vancomycin use utilizing a computer guideline: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998; 5: 554-562. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1998.0050554. PMID: 9824802; PMCID:PMC61335.

- Katherine Lusardi, Brett Bailey, Ramez Awad, Mitchell Jenkins, Juan Carlos Rico Crescencio, Matthew Horak, et al. Leveraging EMR Alerts for vancomycin time outs. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022; 9: 1791.

- Chotiprasitsakul D, Tamma PD, Gadala A, Cosgrove SE. The Role of Negative Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Nasal Surveillance Swabs in Predicting the Need for Empiric Vancomycin Therapy in Intensive Care Unit Patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018; 39: 290-296. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.308. Epub2018 Jan 28. PMID: 29374504.

- Devchand M, Urbancic KF, Khumra S, Douglas AP, Smibert O, Cohen E, et al. Pathways to improved antibiotic allergy and antimicrobial stewardship practice: The validation of a beta-lactam antibiotic allergy assessment tool. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019; 7: 1063- 1065.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.07.048. Epub 2018 Aug 29. PMID:30172019; PMCID: PMC6395557.

- Mabilat C, Gros MF, Van Belkum A, Trubiano JA, Blumenthal KG, Romano A, et al. Improving antimicrobial stewardship with penicillin allergy testing: a review of current practices and unmet needs. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2022; 4: dlac116. doi: 10.1093/jacamr/dlac116. PMID: 36415507; PMCID: PMC9675589.