The Use of Soft Contact Lenses in Veterinary Ophthalmology: A Review and Future Perspectives

- 1. Department of Veterinary Science, University of Parma, Parma, Italy

- 2. CNR-IMEM, Italian National Research Council, Institute of Materials for Electronics and Magnetism, Parma, Italy

- 3. Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Parma, Parma, Italy

- 4. Centre for Regenerative Medicine, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena, Italy

- 5. CERT, Center of Excellence for Toxicological Research, Parma, Italy

Abstract

Background: In human and veterinary medicine Soft Contact Lenses (SCLs) have been used to defend and safeguard the cornea and to promote the healing of corneal lesions. In veterinary ophthalmology SCLs are mainly used in dogs with Spontaneous Chronic Corneal Epithelial Defects (SCCEDs). In cats and horses, the use of SCLs is more limited. Human contact lenses were superior to hydrogel veterinary ones either for retention times and prices. Actually the most used contact lenses in veterinary medicine are the human ones. In the last years. SCLs used for ophthalmic drug delivery were investigated.

Objective and procedures: It could be very interesting and suitable to utilize SCLs as an alternative method to eye drops, which are often uncomfortable techniques for delivering ophthalmic drugs in our pets.

Conclusion and clinical relevance: With 3D printing technology, SCLs can be custom-made to fit the exact specifications of an individual’s eye. This can result in a

Conclusion: Using 3D printing technology, SCLs can be custom made to fit the exact specifications of an individual’s eye. The result is a more comfortable and secure fit, as well as an improvement in the quality of vision. 3D printed SCLs can also incorporate medications, providing a personalized approach to treating eye diseases.

KEYWORDS

- Eye

- Drug delivery

- 3D bioprinting

- Dog

- Cat

- Horse

CITATION

Simonazzi B, Leonardi F, Martini FM, D’Angelo P, Tarabella G, et al. (2024) The Use of Soft Contact Lenses in Veterinary Ophthalmology: A Review and Future Perspectives. JSM Biotechnol Bioeng 9(1): 1094

INTRODUCTION

Contact Lenses (CLs) are medical devices in the shape of a small transparent cap, which are applied to the ocular surface and are used in humans for the correction of most refractive errors or ametropia (myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism).

The birth of the CLs can be traced back to Leonardo da Vinci. Subsequently, in 1636, Descartes perfected Leonardo’s idea, explaining that a tube filled with water and placed on the cornea cancels or reduces the refractive anomalies of the eye.

Modern CLs can be traced back to the discoveries of Fick [1], Kalt [2], and Muller [3]. These researchersbuilt lenses made of glassy material, large in diameter, to rest on the sclera and physiologically poorly tolerated. The first plastic lenses, significantly reducing the weights, were created by Dallos and Feinbloom [4].

Nowadays, it is commonly accepted that the main properties of the materials used for the CLs construction are oxygen permeability, wettability, and biocompatibility. Oxygen permeability is a fundamental characteristic for good tolerability of CLs, because the presence of oxygen is an indispensable factor for corneal metabolism. Wettability is the ability of a liquid to cover a solid surface and is mandatory to the maintain the tear film which is a condition for compatibility between the eye and the lens. Biocompatibility is the absolute lack of adverse reactions by the organism towards a material. All materials used for the construction of CLs have to be biocompatible.

CLs on the market today can be distinguished into Soft Contact Lenses (SCLs) and Hard Contact Lenses (HCLs).

SCLs are made of flexible, water-absorbing and breathable materials such as silicone hydrogel, which allows oxygen to pass through to the cornea and, consequently, helps maintain eye health and reduce the risk of corneal issues. SCLs are designed to conform to the curvature of the eye, providing a comfortable and secure fit for extended periods of time. They are usually more comfortable to wear and easier to adapt compared to hard lenses. In addition, SCLs also offer excellent visual acuity. The lenses sit directly on the surface of the eye, providing a wider field of vision compared to glasses. This can be particularly beneficial for individuals who engage in sports or activities that require a full range of vision without the obstructions of glasses.

HCLs, also known as Rigid Gas Permeable (RGP) lenses, are made of a firm plastic material (polymethylmethacrylate – PMMA) that offer exceptional oxygen permeability. This helps maintain the health of the cornea and reduces the risk of eye infections or discomfort. HCLs maintain their shape on the eye and do not easily tear or deform. They are typically more durable and have a longer lifespan compared to SCLs.

This paper aims to review CLs, describing their features and therapeutic use in human medicine and especially in veterinary medicine. In particular, the review will be focused on the use of CLs as smart drug delivery systems in patients who are not easily treated with drugs administration from the conjunctival mucosa. This review will also consider the futuristic aspects of 3D bioprinting to evaluate the possibility of printing CLs with the active ingredient inside.

CONTACT LENSES IN HUMAN MEDICINE

In human beings, CLs are commonly used for improving vision (to correct vision problems, such as nearsightedness, farsightedness, astigmatism, and presbyopia), but they also have various medical applications in the field of ophthalmology [5,6].

Specialized CLs known as orthokeratology lenses can be used to reshape the cornea overnight, providing temporary relief from conditions such as myopia (nearsightedness) [7]. These lenses are worn at night and removed during the day, allowing patients to see clearly without the need for glasses or traditional CLs during waking hours.

CLs can also be used in the treatment of corneal irregularities, such as keratoconus. Scleral CLs, which are larger in diameter and rest on the white part of the eye (sclera) rather than the cornea, can help provide better vision and comfort for patients with this condition.

Furthermore, dedicated CLs may be employed in the management of dry eye syndrome. Scleral and gas permeable CLs can help protect the cornea and retain moisture on the ocular surface, providing relief.

CLs can also be used for innovative solutions, such as drug delivery purposes [8-10] in case of glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and ocular infections. By incorporating medication into the CLs material, drugs can be released slowly over time, providing continuous therapy and improving patient compliance.

Overall, CLs offer a versatile and effective means of addressing a range of medical issues affecting the eyes. With ongoing advancements in lens technology and design, CLs continue to play a vital role in the field of ophthalmology, providing patients with improved vision and enhanced quality of life [11].

Contact lenses in veterinary medicine

CLs have been used in veterinary medicine since 1970 for various purposes, including therapeutic and diagnostic applications. In recent years, in fact, there has been an increasing interest in utilizing CLs as a treatment option for many ocular pathologies in animals.

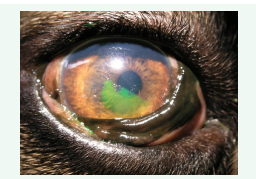

The management of corneal epithelial defects is one of the most common uses of CLs in veterinary medicine because CLs reduce corneal healing time [12-17]. Corneal defects or ulcers are a common ocular condition in dogs, cats, and horses [12,18- 22]. CLs can help protect the cornea from further damage, promote healing, and provide pain relief. CLs offer relief and prevent further corneal damages either in the first phase of the healing, until the ulcer had recovered (in case of superficial corneal erosion or corneal lesion with a small stromal defect) or till surgery is done (e.g., medial trichiasis, entropion). In dogs suffering from dystrophy of the cornea, improved comfort for the animals has been observed [21]. In addition, CLs may also act as a bandage to prevent infection and reduce the risk of scarring. In veterinary ophthalmology, SCLs are mainly used in dogs with Spontaneous Chronic Corneal Epithelial Defects (SCCEDs) [16,17,23-27] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Spontaneous Chronic Corneal Epithelial Defects (SCCEDs) in a Boxer breed dog.

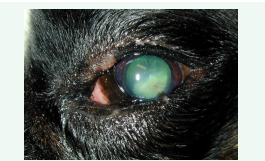

For this pathology, it has been supposed that SCLs may protect the migrating epithelial corneal cells from the harmful mechanical action of the eyelids supporting fast cellular moving. Furthermore, it is likely that SCLs may also supply an occasional exogenous matrix and provided a substrate on which migrating epithelial corneal cells can rise [24] (Figures 2,3).

Figure 2: Corneal neovascularization in a Boxer breed dog with a SCCEDs.

Figure 3: Corneal healing after the treatment with a SCL in combination with Linear Grid Keratotomy (LGK) in a Boxer breed dog with a SCCEDs.

In SCCEDs cases, SCLs may remain in place for a long period (up to 22 days) and significantly improve dogs’ comfort [28]. It has also been demonstrated that the use of SCLs in SCCED occurrence, the lesion had healed in 100% of eyes treated with SCLs whereas only 40% of eyes treated with usual management recovered [25].

Also laboratory trials on rabbits have demonstrated a rapid wound healing in experimentally induced corneal erosions treated with SCLs [24,26].

Always for preventive purposes, SCLs turned out to be useful for the treatment of symblepharon in a 7-month-old intact female Persian cat. After performing a superficial keratectomy, conjunctival tissue was fixed to the corneal limbus with a suture, a soft contact lens was placed, and a temporary tarsorrhaphy was done. This lens not only physically separated the cornea from and the conjunctiva until re-epithelialization occurred, but also relieved eye pain. Complete healing occurred at 3 weeks after surgery [29]. Wada S, et al. [22] documented, in a racehorse with ulcerated corneal damage, the therapeutic utility of SCLs. The use of SCLs, in fact, allowed the animal to be trained and participate in two races.

Another important previously described veterinary use of SCLs is the UV-blocking effect [30]. UV shields are usually contained in each lens. The shielded lenses ensure a 30% reduction of light and are used in animals (especially horses) suffering from photophobia [31]. In particular, animals with scarring or non-visual eyes caused by significant corneal damage can be treated with opaque lenses consisting of a non-transparent covering to prevent any light transmission.

Ling and Smith [32] documented the utility of tinted contact lens for the therapy of a Greyhound suffering from disturbance of vision, disorientation and photophobia caused by left retinal degeneration. The behavior and racing performance of the dog have been significantly improved after the fitting of this lens.

However, the therapeutic efficacy of these lenses is still debated and questionable. Denk N, et al. [30] have evaluated the effect of the UV-blocking in 26 dogs suffering from chronic superficial keratitis (CSK). In the eye with CSK of each dog, UV- blocking contact lens was placed for 6 months, while the other eye with no lens was considered as control eye. No positive effect of UV-blocking CLs in CSK could be proven because in both eyes the pigmentation was increased over the evaluation period.

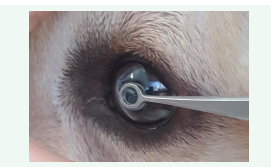

In order to ensure the patient’s welfare, an adequate size of the SCLs should be chosen using the Jameson caliper or based on suggestions from manufacturer company [26]. An inappropriate size of the lens could cause the dislocation or premature loss of the lens [33,21]. Recent new lenses have a much better fitting, are particularly soft and exactly stand into the eye (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Application of a soft contact lens.

These kinds of lenses begin to take on the layout of the cornea after only few minutes [21].

CLs can also be used in the treatment of refractive errors in animals that suffer from conditions such as myopia, hyperopia, and astigmatism, especially when surgery is not an option or is not recommended. In this regard, the use of an aphakic hydrogel contact lens on a monocular dog has been described. This 7-year- old terrier dog was aphakic in the left eye and blind in the right eye because of retinal detachment. Surgical complications have forced the use of aphakic hydrogel contact lens to improve the monocular vision of the dog, who appeared more vigilant, active, and attentive to the surrounding environment with the contact lens [34].

SCLs for drug delivery in case of allergy therapy have been tested on human beings but unfortunately these devices are not commercially available and, consequently, no data in veterinary medicine are available [35,36].

In addition to therapeutic applications, CLs can also be used for diagnostic purposes in veterinary medicine. CLs can help veterinarians get a better view of the ocular structures, such as the retina and optic nerve, during fundus examination and can also aid in the evaluation of tear film quality and corneal health in animals.

Nevertheless, there are some limitations and challenges associated with CLs use in veterinary medicine. One of the main challenges is fitting the appropriate contact lens size and type for each individual animal, as there is a lack of standardized CLs available for veterinary use. In addition, some animals may not tolerate wearing CLs, leading to potential complications such as discomfort, corneal irritation, and infection.

Corneal damages induced by lens wear in veterinary medicine

In veterinary literature, there are very few works that report damage to the eye caused by the lenses. In 1992 Madigan and Holden [37] reported a case of reduced epithelial adhesion in cat cornea after extended contact lens wear. The researchers have documented a decrease in the number of cell layers and hemidesmosomes per micrometer of basement membrane, that was likely to be directly related to the decrease of epithelial adhesion.

A presumed contact lens-induced intracorneal hemorrhage characterized by an annular pattern has also reported in a 10-year-old castrated male miniature poodle dog with diabetes mellitus [38]. A spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defect was diagnosed, so the dog was fitted with a contact lens as a bandage. The epithelial defect improved within a week but an annular intracorneal hemorrhage was found, so the contact lens was removed, and the hemorrhage resolved in 30 days.

Human silicone CLs versus veterinary hydrogel CLs

The most currently used CLs in veterinary medicine are the Bausch & Lomb Purevision because they are extended wear lenses which dogs and cats can safely and continuously have in their eyes for a few weeks, even during sleep. Purevision CLs allow oxygen to pass through to the cornea and the surface of the lenses and to naturally keep the eye moist in order to aid healing of the damage.

In 2018 Braus BK, et al. [39] compared two different types of CLs (single sized human silicone contact lens ‘PureVision 2’ [Bausch & Lomb Incorporated, Rochester, NY, USA] and specially designed veterinary hydrogel contact lens ‘AcriVet Pat D’ [Bausch & Lomb Incorporated]) used as a bandage in 12 healthy Beagle eyes. The retention times and the effects of the lenses regarding irritation of the eye, changes in tear production, impact of CLs on tonometer readings, and cytological and microbiological alterations were evaluated. The mean retention times for specially designed veterinary hydrogel CLs were significantly shorter (2 days) than for human silicon lenses (> 1 week). Irritation of the eye was low for both type of lenses even though severe keratoconjunctivitis was caused by folding and displacement of the human CLs was recorded in one dog. Tear production remained stable in dogs with human CLs while intraocular pressure readings with specially designed veterinary hydrogel CLs were only slightly altered. Cytology revealed a slight and non-significant increase in neutrophilic granulocytes with both types of lenses, whereas the microflora did not significantly change. Based on anatomical and clinical aspects of the treated eyes and the characteristics of the used lenses, the authors concluded that human silicone CLs were superior to hydrogel veterinary lenses regarding retention times (4× longer compared to veterinary lenses) and costs (approximately 1/10th of veterinary lenses). Moreover, the authors suggest that it is not necessary to use lenses with species specific features as bandage. Given that silicone lenses fulfill the requirement of being thinner, the authors pointed out that this material may be a better choice also for veterinary lenses. In conclusion, Braus BK, et al. [39] recommend the use of both types of lenses in canine eyes.

In addition, Diehl KA, et al. [17] confirmed that, although all CLs used as bandage were well tolerated and easy to use, human CLs were better maintained and lasted longer than veterinary ones. Specifically, Johnson and Johnson Vision Care Acuvue® Oasys™ with Hydraclear™ Plus lenses were retained significantly longer than all veterinary lenses, and Bausch and Lomb PureVision® 2 lenses were retained significantly longer than Keragenix HydroBlues™ 18 and AnimaLens™ HRT 78 18 mm lenses.

In accordance with previous studies, Dees DD, et al. [27] underline that Pure Vision lenses have an improved retention rate compared to Acrivet ones and showed that SCLs used as bandage in 237 dogs with SCEEDs significantly improved healing times of the cornea [40].

SCLs as drug delivery systems

The main drawback in the administration of drugs, in the form of drops, into the eye is their reduced availability due to the constant blinking of the eyelids and the constant tears production.

To overcome this problem, the use of CLs as a kind of leakage- limiting bandage of administered drugs and as tools for controlled and intelligent drug release has been opened up.

The therapeutic goal of CLs is to increase the bioavailability and retention of drugs at the corneal level, improving their efficacy [10] and patient welfare [41]. It is likely that therapeutic effects are affected by the kind of drug formulation [42],

CLs loaded with timolol have been experimentally studied on glaucomatous beagle dogs [43,44]. Glaucoma is one of the most common causes of blindness in human beings and animals and its therapy consists of administration of eye drops which reduce the intraocular pressure (IOP). These studies demonstrated the potential advantages of delivering ophthalmic drugs through CLs for the treatment of glaucoma. CLs used on daily basis achieved same efficacy as eye drops but with only 20% of the drug loading. Incorporation of vitamin E (ACUVUE® TruEyeTM with 20% vitamin E) into the lenses can significantly increase the drug release duration from a few hours to several days, and IOP can be significantly lowered. No sign of discomfort or ocular toxicity was observed for contact lens wear.

It has also been demonstrated that SCLs loaded which nanoparticles of propoxylated glyceryl triacylate reduced the IOP lengthening the drug release in dogs [41,45].

Nevertheless, a critical point is the accuracy of IOP measurements through the SCLs, because one of the most challenging points of the glaucoma therapy is the continuous monitoring of IOP. In vivo studies highlighted that the IOP measurement could be easily and correctly done without removing the lenses in dogs [46,47].

More recently in 2022 it has been reported the use of smart SCLs for continuous 24-hour monitoring of IOP in glaucoma treatment. These devices maintained biocompatibility, softness, transparency, oxygen and nutrient permeability of traditional SCLs. These lenses are able to adapt to corneal curvatures, allowing accurate IOP measurements in both humans and animal models (rabbit and dog), making them an excellent assessment tool improving patient comfort, accuracy and repeatability of IOP measurements [48].

Thus, the goal in the next few years should be to manufacture ophthalmic devices with controlled drug release. In this regard, it should be investigated whether to load existing commercially available CLs with suitable formulations with drugs or to use another field of biosciences: 3D bioprinting.

The latest therapeutic CLs proposed to improve CLs properties with the final aim of treating ocular conditions are listed in (Table 1).

Table 1: List of the latest solutions for therapeutic CLs and related references.

|

Contact lenses (CLs) |

Model |

CLs Fabrication Technique |

Advantages/DisadVantages |

References |

|

Ganciclovir loaded microparticles Hydrogel CLs to prevent ocular irritation |

Chorioallantoic membrane of 9 day incubated chicken eggs |

Radical polymerization, mixed with ganciclovir loaded microparticles |

High bioavailability, prolonged drug release |

[49] |

|

Hydrogel CLs Material Containing Magnesium Oxide Nanoparticles and 3-(Trifluoromethyl) styrene |

- |

Cast molding polymerization |

High water content, wettability, oxygen permeability, and antibacterial properties. |

[50] |

|

Covalent cross-linking of chitosan for electrofabrication of hydrogel CLs |

HUVEC cells to evaluate biocompatibility, Staphylococcus aureus to evaluate adhesion properties |

Electrochemical cross-linking of chitosan and epichlorohydrin induced by electrodeposition |

Mild reaction conditions, high efficiency, low energy consumption, environmental friendliness. Epichlorohydrin Improves trasmittance and mechanical resistance. |

[51] |

|

Soft hydrogel CLs for posterior segment eye diseases treatment. |

- |

injection molding and thermal curing |

Narigerin controlled drug release of 72–82% for 24 h, faster (90% of narigerin released in the first five hours) with soak and release method. |

[52] |

|

Antibacterial releasing CLs to treat bacterial keratitis. |

Human corneal epithelial cells (HCEC) to evaluate cytotoxicity. Rabbit implantation showed effective control of the bacteria- infected cornea |

Electrostatic coating: the positively charged vancomycin-incorporated chitosan nanoparticles were used for layer-by-layer deposition with negatively charged heparin, obtaining a polyelectrolyte multilayer on the lens surface |

Biocompatibility, antibacterial activity, good hydrophilicity |

[53] |

|

Commercial hydrogel CLs integrated with Au/Ag nanoparticles |

- |

breathing-in/breathing-out (BI−BO) method |

Stability is preserved for a month. Treatment maintains wettability and water content. |

[54] |

|

Gelatin hydrogel/CLs composites as rutinity delivery systems to promote corneal wound healing. |

HCEC cells to assess cytotoxicity and wound healing. Rabbit implantation to evaluate biocompatibility, wound healing and proteome |

In situ free-radical polymerization and carboxymethyl cellulose/N- hydroxysulfosuccinimide crosslinking reactions |

Bioavailability (14 days), biocompatibility. Proteomic studies show that corneal wound healing can be promoted by ERK/ MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. |

[55] |

|

Zwitterionic Nanogel CLs based on poly (sulfobetaine methacrylate) embedded with levofloxacin. |

Mouse embryo fibroblast (3T3) cell lines |

Cast molding method via free radical polymerization |

Drug release for 10 days, biocompatibility |

[56] |

|

Hyaluronic acid and silver incorporated bovine serum albumin porous CLs for the treatment of alkali- burned corneal wound |

HCEC Cell line Mice implantation |

Cross Linking with N-Hydroxy succinimide and N-(3- dimethylaminopropyl)-N′- ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride in acid conditions |

Corneal healing rate was enhanced, corneal opacification and neovascularization were lessened, and the inflammation response was reduced in mice |

[57] |

|

Pirfenidone loaded soft CLs to prevent proliferative ocular diseases |

HCEC Cell line Rabbit implantation |

Insertion of pirfenidone and polyvinyl alchol into two layers of silicone films, polymerised at 60°C |

Prolonged drug capacity and release Higher thickness than commercially ones (less comfort). More expensive than eye drops. |

[58] |

|

Gatifloxacin-Pluronic-loaded contact lens to dissolve the gatifloxacin precipitates and improve optical properties of the lens |

- |

free radical polymerization/cast molding method |

Need to optimize the Plackett-Burman experimental design |

[59] |

|

Drug-eluting contact lens containing cyclosporine-loaded cholesterol- hyaluronate micelles for dry eye treatment |

Rabbits implantation |

Photopolymerization |

Good properties of CLs cyclosporine/C-HA micelle. |

[60] |

|

Gold nanoparticles CLs uptake and release timolol |

Rabbits implantation |

Gold nanoparticles were synthesized by reducing the chloroauric acid (HAuCl4) with tri- sodium citrate dihydrate |

Critical lens properties are not compromised by gold nanoparticles |

[59] |

|

Cyclosporine A-eluting porous CLs for the Treatment of Dry Eye |

Rabbits implantation (Draize test, ELISA and PAS stain, Schirmer’s test) |

Thermal polymerization |

Continuous drug release (48h-72h); improvement of clinical parameters and density of conjunctival goblet cells and reduction of inflammatory cytokines. |

[61] |

|

Molecular Imprinted Structural Color CLs |

|

Molecular imprinting and polymerization by UV irradiation. Removal of SiO2 and imprinted molecule |

Increase the loading amount and the residence time of the drug. Timolol release control by colour changing, possible application to other drugs |

[62] |

3D BIOPRINTING

3D bioprinting is a revolutionary technology that involves the use of 3D printers to create complex biological structures that mimic the natural human and animal tissues and organs using bio- ink made from living cells. 3D bioprinting could be used to create personalized implants and prosthetics, generate tissues for drug testing and disease modeling, and organs for transplantation. Not least, 3D bioprinting could give great impetus to the production of printed CLs that are already loaded with drugs.

However, there are several challenges that need to be overcome in order to fully realize the potential of 3D bioprinting, such as the need for more advanced bio-inks, better printing techniques, and the ability to vascularize the tissues to ensure proper nutrient delivery.

3D Bioprinting contact lenses

3D printed CLs are a relatively new development in the world of ophthalmology. Traditional CLs are typically mass-produced in standard sizes and shapes, which may not fit perfectly for every individual’s unique eye shape and size.

With 3D printing technology, CLs can be custom-made to fit the exact specifications of an individual’s eye. This can result in a more comfortable and secure fit, as well as improved vision quality. This can improve comfort of human and animal patients with specific eye conditions, irregular corneas or particular pathologies.

Additionally, 3D printed CLs can also incorporate drugs, offering a personalized approach to the treatment of eye diseases. Medications or therapeutic agents can be embedded into the contact lens material and released gradually over time, providing a more efficient and targeted way of delivering drugs to the eye. 3D printed CLs are still in the early stages of development, but it has the undoubted advantage of reducing the dose of drug to be administrated due to less waste and improving patient compliance.

Thus, 3D bioprinting technology has the potential to significantly enhance the functionality and performance of CLs, making them more personalized and effective for individual needs.

Specificity of 3D printed CLs

Additive manufacturing is made up of seven families, three of which use powders or filaments, binder jetting, and directed energy deposition, another three use liquid or molten materials (material-extrusion, material-jetting and VAT polymerisation), the seventh uses laminated sheets.

There are many papers that describe the use of 3D printing in ophthalmology, but only 8 papers describe the 3D printing of CLs (Table 2).

Mohamdeen YMG, et al. [63] developed a first device useful for drug release using FDM technologies. The objective was to test the release of the drug through a filament specifically produced. The release of the active ingredient lasted 3 days, but the roughness and difficult reabsorption typical of these materials/technologies appear to be highly limiting.

With the aim of completely absorbing the scaffold upon contact with the eye, Choi JH, et al. [61] used DIW technology. This technology allows to print biodegradable and bioresorbable materials starting from a fluid loaded into a syringe. Their flexible structure certainly improves ergonomics compared to rigid lenses, but overall the gradual release of the active ingredient remains difficult to manage. In fact, approximately 50% of the drug is released within the first day and then stabilizes in the following 14 days, thus requiring an increase in performance through new composite materials, as described by Zidan A, et al. [64], who adopted the use of the silicone fixed via photopolymerization.

Therefore, the application of a polymerizable composite material appears to be a de facto driver of improvement, and Alam A, et al. [65] studied printability starting from DLP technologies, analysing the printing parameters of a contact lens such as the orientation of the object, the roughness of the surface, the transparency of the lens and its potential in terms of customization. Different types and functionalizations of lenses are developed up to scaffolds intended for sun protection in order to replace sunglasses or correct colour vision deficiency.

Moreover, Hisham H, et al. [66] presented a multi-material technique for the development of bio-composite lenses, dedicated to the release of active ingredients by stratifying them within the same lens, by changing the tray and integrating partial processes. Chen Y, et al. [67] explored problems related to surface roughness and transparency, solving them via continuous projection during the lifting of the Z axis starting from a confined surface.

In conclusion, DLP/SLA [67] technology seems to be the preferable technology for the development of lenses in order to guarantee resistance, durability over time, flexibility and almost total customization. By introducing concepts such as bio- composite scaffolds and partial processes [68], it allows achieve a high level of customization and reproducibility. However, there are still numerous improvements to be implemented, as well as the complex industrial scalability required for medical devices [69], including FDM [70] and DIW [68] technologies too.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Compared to eye drops, SCLs are a more natural technique to administer ophthalmic drugs thanks to the nearness of these devices to the cornea. SCLs consist of hydrogel able to absorb fixed volume of aqueous vehicle, including drug and nanoparticles inside polymerizable monomers solution able to manage the related release and to reduce side effects due to systemic absorption [71]. Therefore, therapeutic SCLs for drug delivery may overcome the following main drawbacks of traditional eye drops: low drug bioavailability, low duration of action of drug, low patient welfare, frequent drug administration, and systemic toxicity [72]. Moreover, the drug released by the SCLs remains in the tear film for prolonged time of at least 30 minutes allowing the drug to achieve therapeutic concentration in the most part of the cornea and demonstrated that the bioavailability increases to about 50% with SCLs. Unfortunately, available SCLs require SCLs daily replacement at least.

Therefore, the viability of this drug administration method should be significantly improved by using new approaches, such as bioprinting, hydrogels, bio-composite materials and partial processes, that enable the ability to design medical devices aiming to fit the functional ability required. In particular, DIW enables the ability to print GelMA-based bioresorbable lenses, but the management of long-term drug release is still difficult, while lens performances should be improved via PEGDA. This last material was the most used material with GelMA and HEMA for the DIW and VAT polymerisation manufacturing approaches, respectively. Moreover, designing bio-composite materials showed the ability of bioprinting to reproduce stratified lenses with localised deposition of different materials via DLP technology, that it should be merged with the continuous printing mode to scale industrially a first medical device.

The most recent studies aimed to design SCLs able to lengthen drug release also for several days. In particular, SCLs loaded with vitamin E seem to be suitable for lengthening drug release to the cornea in dogs [73].

In conclusion, aiming to quantitatively evaluate in-vivo the efficacy of topical medications loaded in SCLs determining whether their effects can be modulated, we described, in the present review, the bases of this new clinical customization field of bioprinting, enabling the ability of clinicians, bioengineers and researchers to design new experimental studies related to SCLs, customised for drug delivery systems and specifically designed towards greater effectiveness in subjective human and animal therapy.

REFERENCES

- Fick E. Über den durchmesser der sehorgane und die brechkraft der linse. Archiv für Anatomie und Physiologie. 1888; 165-194.

- Kalt H. Über die Verwendung von Kontaktlinsen zur Korrektion von Fehlsichtigkeiten. Klinische Monatsblätter für Augenheilkunde. 1929; 82: 626-635.

- Muller A. Die Anpassung von Kontaktlinsen. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 1936; 135: 1-18.

- Dallos P, Feinbloom W. A Method for Producing a Methyl Methacrylate Plastic Contact Lens. Am J Optometry and Arch Am Ac Optometry. 1948; 25: 381-386.

- Daglioglu MC, Coskun M, Ilhan N, Tuzcu EA, Ilhan O, Keskin U, et al. The effects of soft contact lens use on cornea and patient’s recovery after autograft pterygium surgery. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2014; 37: 175-177.

- Maurizi E, Schiroli D, Atkinson SD, Mairs L, Courtney DG, O’Hagan B, et al. A novel role for CRIM1 in the corneal response to UV and pterygium development. Exp Eye Res. 2019; 179: 75-92.

- Lim L, Lim EWL. Therapeutic contact lenses in the treatment of corneal and ocular surface diseases-a review. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2020; 9: 524-532.

- Patel A, Cholkar K, Agrahari V, Mitra AK. Ocular drug delivery systems: An overview. World J Pharmacol. 2013; 2: 47-64.

- Franco P, De Marco I. Contact lenses as ophthalmic drug delivery systems: A Review. Polymers (Basel). 2021; 13: 1102.

- Mustfa SA, Maurizi E, McGrath J, Chiappini C. Nanomedicine approaches to negotiate local biobarriers for topical drug delivery. Advanced Therapeutics. 2021; 4: 2000160.

- Pucker AD, Tichenor AA. A Review of contact lens dropout. Clin Optom (Auckl). 2020; 12: 85-94.

- Dice PF, Cooley PL. Peripheral corneal ulcers in the horse. Equine Vet J Suppl. 1990; 10: 18-21.

- Bentley E, Murphy CJ. Thermal cautery of the cornea for treatment of spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects in dogs and horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004; 224: 250-253, 224.

- Nevile JC, Hurn SD, Turner AG, Morton J. Diamond burr debridement of 34 canine corneas with presumed corneal calcareous degeneration. Vet Ophthalmol. 2016; 19: 305-312.

- Chow DW, Westermeyer HD. Retrospective evaluation of corneal reconstruction using ACell Vet(™) alone in dogs and cats: 82 cases. Vet Ophthalmol. 2016;19: 357-366.

- Spertus CB, Brown JM, Giuliano EA. Diamond burr debridement vs. grid keratotomy in canine SCCED with scanning electron microscopy diamond burr tip analysis. Vet Ophthalmol. 2017; 20: 505-513.

- Diehl KA, Bowden AC, Knudsen D. Bandage contact lens retention in dogs-A pilot study. Vet Ophthalmol. 2019; 22: 584-590.

- Schmidt GM, Blanchard GL, Keller WF. The use of hydrophilic contact lenses in corneal diseases of the dog and cat: A preliminary report. J Small Anim Pract. 1977; 18: 773-777.

- Tammeus J, Krall CJ, Rengstorff RH. Therapeutic extended wear contact lens for corneal injury in a horse. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1983; 182: 286.

- Chavkin MJ, Riis RC, Scherlie PH. Management of a persistent corneal erosion in a boxer dog. Cornell Vet. 1990; 80: 347-356.

- Bossuyt SM. The use of therapeutic soft contact bandage lenses in the dog and the cat: A series of 41 cases. Vlaams Diergeneeskd Tijdschr. 2016; 85: 343-348.

- Wada S, Yoshinari M, Mizuno Y. Practical usefulness of a therapeutic soft contact lens for a corneal ulcer in a racehorse. Vet Ophthalmol. 2000; 3: 217-219.

- Kirschner SE. Persistent corneal ulcers. What to do when ulcers won’t heal. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1990; 20: 627-642.

- Gosling AA, Labelle AL, Breaux CB. Management of spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects (SCCEDs) in dogs with diamond burr debridement and placement of a bandage contact lens. Vet Ophthalmol. 2013; 16: 83-88.

- Grinninger P, Verbruggen AM, Kraijer-Huver IM, Djajadiningrat- Laanen SC, Teske E, Boevé MH. Use of bandage contact lenses for treatment of spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects in dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 2015; 56: 446-449.

- Wooff PJ, Norman JC. Effect of corneal contact lens wear on healing time and comfort post LGK for treatment of SCCEDs in boxers. Vet Ophthalmol. 2015; 18: 364-370.

- Dees DD, Fritz KJ, Wagner L, Paglia D, Knollinger AM, Madsen R. Effect of bandage contact lens wear and postoperative medical therapies on corneal healing rate after diamond burr debridement in dogs. Vet Ophthalmol. 2017; 20: 382-389.

- Martinez E, Ortiz M, Salas V. Clinical usefulness of hydrophilic bandage lenses. Proc Europ Soc Vet Oph. 2010: 349.

- Kim Y, Kang S, Seo K. Application of superficial keratectomy and soft contact lens for the treatment of symblepharon in a cat: a case report. J Vet Sci. 2021; 22: e19.

- Denk N, Fritsche J, Reese S. The effect of UV-blocking contact lenses as a therapy for canine chronic superficial keratitis. Vet Ophthalmol. 2011; 14: 186-194.

- Veterinary Speciality Products. SJ Hales Ltd- Farm and Veterinary Products 2024.

- Ling T, Smith J. Tinted contact lenses for treatment of retinal degeneration in a Greyhound. JAVMA. 1986; 188: 65-67.

- Morgan RV, Bachrach A, Ogilvie GK. An evaluation of soft contact lens usage in the dog and cat. JAAHA. 1984; 20: 885-888.

- Yeung KK, Silverman BS, Kageyama JY. Aphakic hydrogel contact lens fitting on a monocular canine: a case report. Optometry. 2001; 72: 421-425.

- Gause S, Hsu KH, Shafor C, Dixon P, Powell KC, Chauhan A. Mechanistic modeling of ophthalmic drug delivery to the anterior chamber by eye drops and contact lenses. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2016; 233: 139- 154.

- Rykowska I, Nowak I, Nowak R. Soft contact lenses as drug delivery systems: A review. Molecules. 2021; 26: 5577.

- Madigan MC, Holden BA. Reduced epithelial adhesion after extended contact lens wear correlates with reduced hemidesmosome density in cat cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992; 33: 314-23.

- Jung S, Park SA. Case report: Presumed contact lens-induced intracorneal hemorrhage in a diabetic dog. Front Vet Sci. 2022; 9: 959782.

- Braus BK, Riedler D, Tichy A, Spergse RJ, Schwendenwein I. The effects of two different types of bandage contact lenses on the healthy canine eye. Vet Opht. 2018; 21: 477-486.

- Dees DD, Fritz KJ, Wagner L, Paglia D, Knollinger AM, Madsen R. Effect of bandage contact lens wear and postoperative medical therapies on corneal healing rate after diamond burr debridement in dogs. Vet Opht. 2017; 20: 382-389.

- Jung JH, Abou-Jaoude M, Carbia BE, Plummer C, Chauhan AJ. Glaucoma therapy by extended release of timolol from nanoparticle loaded silicone-hydrogel contact lenses. Control Release. 2013; 165: 82-89.

- Hatzav M, Bdolah-Abram T, Ofri R. Interaction with therapeutic soft contact lenses affects the intraocular efficacy of tropicamide and latanoprost in dogs. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2016; 39: 138-143.

- Peng CC, Burke MT, Carbia BE, Plummer C, Chauhan A. Extended drug delivery by contact lenses for glaucoma therapy. J Control Release. 2012; 162: 152-158.

- Peng CC, Ben-Shlomo A, Mackay EO, Plummer CE, Chauhan A. Drug delivery by contact lens in spontaneously glaucomatous dogs. Curr Eye Res. 2012; 37: 204-211.

- Alvarez-Lorenzo C, Haruyiki Hiratani J, Gómez-Amoza L, Martínez- Pacheco R, Souto C, Concheiro A. Soft contact lenses capable of sustained delivery of timolol. J Pharm Sci. 2002; 91: 2182-2192.

- Miller PE, Murphy CJ. Intraocular pressure measurement through two types of plano therapeutic soft contact lenses in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 1995; 56: 1418-1420.

- Ahn, JT, Jeong MB, Park YW, Kim SE, Ahn JS, Lee YR, et al. Accuracy of intraocular pressure measurements in dogs using two different tonometers and plano therapeutic soft contact lenses. Vet Opht. 2012; 15: 83-88.

- Zhang J, Kim K, Kim HJ, Meyer D, Park W, Lee SA, et al. Smart soft contact lenses for continuous 24-hour monitoring of intraocular pressure in glaucoma care. Nat Commun. 2022; 13: 5518.

- Harsolekar M, Ansari M, Supe S, Singh K. Formulation development and evaluation of therapeutic contact lens loaded with ganciclovir. Int Ophtalmol. 2023; 43: 2225-2236.

- Lee DJ, Scruggs BA, Sánchez E, Thomas M, Faridi A. Transient vision loss associated with prefilled aflibercept syringes: A case series and analysis of injection force. Ophthalmol Sci. 2022; 2: 100115.

- Yang C, Wang M, Wang W, Liu H, Deng H, Du Y, et al. Electrodeposition induced covalent cross-linking of chitosan for electrofabrication of hydrogel contact lenses. Carbohydr Polym. 2022; 292: 119678.

- Chau Thuy Nguyen D, Dowling J, Ryan R, McLoughlin P, Fitzhenry L. Controlled release of naringenin from soft hydrogel contact lens: An investigation into lens critical properties and in vitro release. Intern J Pharmac. 2022; 621: 121793.

- Wang R, Lu D, Wang H, Zou H, Bai T, Feng C, et al. “Kill-release” antibacterial Ahmed polysaccharides multilayer coating based therapeutic contact lens for effective bacterial keratitis treatment. RSC Adv. 2021; 11: 26160-26167.

- Salih AE, Elsherif M, Alam F, Alqattan B, Yetisen AK, Butt H. Syntheses of gold and silver nanocomposite contact lenses via chemical volumetric modulation of hydrogels. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2022; 8: 2111-2120.

- Zhao L, Qi X, Cai T, Fan Z, Wang H, Du X. Gelatin hydrogel/contact lens composites as rutin delivery systems for promoting corneal wound healing. Drug delivery. 2021; 28: 1951-1961.

- Wang Z, Li X, Zhang X, Sheng R. Novel contact lenses embedded with drug-loaded zwitterionic nanogels for extended ophthalmic drug delivery. Nanomaterials. 2021; 11: 2328.

- Yin C, Qi X, Wu J, Guo C, Wu X. Therapeutic contact lenses fabricated by hyaluronic acid and silver incorporated bovine serum albumin porous films for the treatment of alkali-burned corneal wound. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021; 184: 713-720.

- Wu C, Or PW, Chong JIT, Pathirage Don IKK, Lee CHC, Wu K, et al. Extended delivery of pirfenidone with novel, soft contact lenses in vitro and in vivo. Journal of ocular pharmacology and therapeutics. 2021; 37: 75-83.

- Maulvi FA, Patil RJ, Desai AR, Shukla MR, Vaidya RJ, Ranch KM, et al. Effect of gold nanoparticles on timolol uptake and its release kinetics from contact lenses: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. Acta Biomater. 2019; 86: 350-362.

- Mun J, Mok JW, Jeong S, Cho S, Joo CK, Hahn SK. Drug-eluting contact lens containing cyclosporine-loaded cholesterol-hyaluronate micelles for dry eye syndrome. RSC Adv. 2019; 9: 16578-16585.

- Choi JH, Li Y, Jin R, Shrestha T, Choi JS, Lee WJ, et al. The efficiency of cyclosporine a-eluting contact lenses for the treatment of dry eye. Curr Eye Res. 2019; 44: 486-496.

- Deng J, Chen S, Chen J, Ding H, Deng D, Xie Z. Self-reporting colorimetric analysis of drug release by molecular imprinted structural color contact lens. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018; 10: 34611-34617.

- Mohamdeen YMG, Tabriz AG, Tighsazzadeh M, Nandi U, Khalaj R, Andreadis I, et al. Development of 3D printed drug-eluting contact lenses. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2021; 74: 1467-1476.

- Zidan A, Alayoubi A, Asfari S, Coburn J, Ghammraoui B, Aqueel S, et al. Development of mechanistic models to identify critical formulation and process variables of pastes for 3D printing of modified release tablets. Int J Pharm. 2019; 555: 109-123.

- Alam F, Elsherif M, AlQattan B, Salih A, Lee SM, Yetisen AK, et al. 3D Printed Contact Lenses. Biosensor. 2022; 12: 654.

- Hisham H, Salih AE, Butt H. 3D printing of multimaterial contact lenses. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2023; 9: 4381-4391.

- Chen Y, Wang T, Zhang G. Research on parameter optimization of micromilling Al7075 based on edge-size-effect. Micromachines. 2020; 11: 197.

- Ahmed I, Sullivan K, Prive A. Multi-Resin Masked Stereolithography (MSLA) 3D printing for rapid and inexpensive prototyping of microfluidic chips with integrated functional components. Biosensors. 2022; 12: 652.

- Foresti R, Rossi S, Pinelli S, Alinovi R, Barozzi M, Sciancalepore C, et al. Highly-defined bioprinting of long-term vascularized scaffolds with Bio-Trap: Complex geometry functionalization and process parameters with computer aided tissue engineering. Materialia. 2020; 9: 100560.

- Mamo HB, Adamiak M, Kunwar A. 3D printed biomedical devices and their applications: A review on state-of-the-art technologies, existing challenges, and future perspectives. J Mech Behav Biomed Mat. 2023; 143: 105930.

- Foresti R, Ghezzi B, Vettori M, Bergonzi L, Attolino S, Rossi S, et al. 3D printed masks for powders and viruses safety protection using food grade polymers: Empirical tests. Polymers. 2021; 13: 617.

- Gourishanker J, Kumar A. Drug delivery through soft contact lenses: An introduction. Chron Young Sci. 2011; 2: 3-6.

- Pratumjorn N, Pumipuntu N, Kusolsongkhrokul R, Lorsirigool A. The use of soft contact bandage lenses for corneal ulcer in dogs and cats: A review. World Vet J. 2022; 12: 128-132.