Splenic Infarction Revealing A Complex Congenital Cardiopathy in A 49-Year-Old Adult: Case Report

- 1. Department of Cardiology, Bogodogo University Hospital, Burkina Faso

- 2. Department of Nephrology, Bogodogo University Hospital, Burkina Faso

- 3. Department of Cardiology, Yalgado OUEDRAOGO University Hospital, Burkina Faso

Abstract

Introduction: Splenic infarction is the consequence of splenic parenchymal ischaemia related to occlusion of the splenic artery or one of its branches. We report a case of splenic infarction associated with a complex congenital heart disease discovered in adulthood.

Clinical observation: A 49-year-old sedentary female patient was admitted with progressive moderate pain in the left hypochondrium and dyspnoea. Clinical examination revealed auscultatory arrhythmia, exquisite left hypochondral pain and congestive heart failure syndrome. The electrocardiogram showed atrial fibrillation, while the echocardiogram showed an atrioventricular canal and a single right ventricle. The chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly with significant protrusion of the pulmonary artery. Abdominal angioscan was consistent with splenic infarction, while the laboratory work-up was normal. Complex congenital heart disease associating an atrioventricular canal and a single ventricle decompensated into congestive heart failure complicated by atrial fibrillation with splenic infarction was the diagnosis adopted. The patient was treated with furosemide, enalapril, spironolactone and enoxaparin. The patient died on the third day of hospitalization.

Conclusion: This observation shows that in the absence of early diagnosis and appropriate treatment, complex congenital heart disease can lead to major complications, particularly thromboembolic.

KEYWORDS

- Splenic infarction

- Atrioventricular canal

- Single ventricle

- Ouagadougou

CITATION

NACANABO MW, MAMA SIKA M, SEGHDA AT, TALL/THIAM A, YAMEOGO VN, et al. (2025) Splenic Infarction Revealing A Complex Con- genital Cardiopathy in A 49-Year-Old Adult: Case Report. JSM Clin Case Rep 13(1): 1255.

INTRODUCTION

Splenic infarction is a rare, potentially serious condition characterised by necrosis of splenic tissue due to interruption of the blood supply [1]. In patients with complex congenital heart disease, splenic ischaemia is usually due to a thromboembolic complication [2]. Congenital heart disease is a heterogeneous group of structural anomalies of the cardiovascular system that are present from birth and derive from abnormalities in embryonic development [3]. Their prevalence is estimated at between 6 and 8 per 1000 live births worldwide [3]. Complex forms are often associated with abnormalities of the spleen and abnormal arrangement of other thoraco- abdominal organs [4]. Among these complex pathologies seen in adults are univentricular hearts, Ebstein’s anomaly of the tricuspid valve and corrected transposition of the great vessels [5]. We describe an unusual situation in which a splenic infarction was the primo movens for the discovery of a complex congenital heart disease associating an atrioventricular canal (AVC) and a right-type single ventricle (SUV).

CLINICAL OBSERVATION

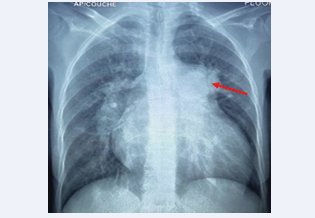

The patient was a 49-year-old housewife. The patient’s cardiovascular risk factors included a sedentary lifestyle. She presented with progressive onset, moderate-intensity pain in the left hypochondrium, associated with New York Health Association stage 2 dyspnoea, evolving in an apyretic context. Clinical examination revealed a blood pressure of 118/82 mmHg, an auscultatory arrhythmia with a heart rate of 108 beats per minute, palpatory pain in the left hypochondrium and a global heart failure syndrome. An emergency electrocardiogram revealed atrial fibrillation (AF). The chest X-ray showed significant cardiomegaly with major dilatation of the pulmonary artery and pulmonary hypervascularisation (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Front chest X-ray showing cardiomegaly, major dilatation of the pulmonary artery (red arrow) and pulmonary hypervascularisation

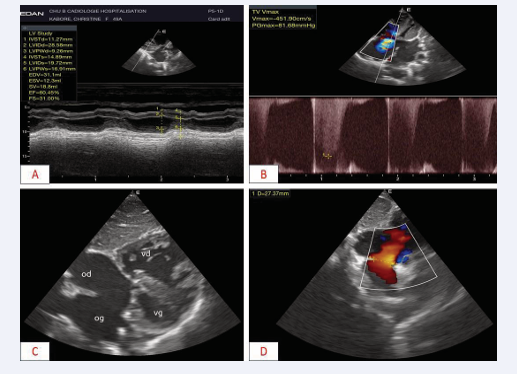

Transthoracic Doppler echocardiography revealed complex heart disease with mitral hypoplasia, a common atrioventricular canal and a single right ventricle (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Transthoracic Doppler echocardiography showing complex heart disease A: Para-sternal long-axis section, transventricular TM showing good systolic function B: Apical 4-cavity incidences, grade three Doppler IT with C & D: Subcostal 4-cavity view, complete atrioventricular canal, with single right ventricle

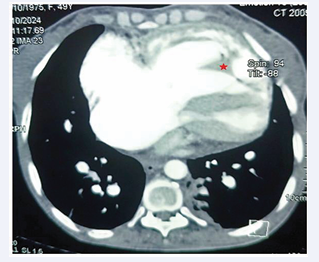

There was also grade III pulmonary insufficiency with severe pulmonary hypertension (80 mmHg). Abdomino- pelvic angioscan revealed a patch of intra-parenchymal splenic hypodensity suggestive of an upper mid-polar splenic infarction measuring 39x33x36 (Figure 3); the other viscera were normal. Biological tests were normal.

Figure 3: Axial-section injected abdomino-pelvic angioscan showing an upper mid-polar splenic infarct measuring 39x33x36 (star).

The diagnosis of a complex congenital heart disease combining VAD and right VU heart decompensated into congestive heart failure of late onset complicated by AF associated with splenic infarction was accepted. The patient was treated with drugs, including furosemide, enalapril, spironolactone and curative doses of low molecular weight heparin. The patient died on the third day of hospitalisation as a result of haemodynamic failure.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of congenital heart disease in sub- Saharan Africa is estimated at around 8 per thousand live births [6]. Adult patients with congenital heart disease may slip through the net of the health care system and only be discovered at the stage of complications. In fact, the main concern when heart disease is discovered in an adult is the presence of irreparable complications [7]. The case in our study was a 49-year-old adult who had never been diagnosed with heart disease. She was referred for chest pain and dyspnoea. The most frequent circumstances of discovery were dyspnoea (47.5%), heart murmur (35.3%), congestive heart failure (13.4%) and cyanosis (9.7%) [8]. These symptoms, although non- specific, point to a multitude of complex congenital heart diseases. Among septal defects, atrial septal defect (ASD) and ventricular septal defect (VSD) are the most common (15% and 10% respectively) in adults [5,9]. The single ventricle heart is extremely rare in adults. The absence of a subpulmonary ventricle leads to chronic systemic venous hypertension, markedly impaired pulmonary haemodynamics and a chronically ‘preload deprived’ ventricle [10]. Although 10-year survival can approach 90%, it must be understood that a premature decline in cardiac performance, with reduced survival, is inevitable [10]. Important haemodynamic problems contributing to late Fontan failure include progressive decline in systemic ventricular function, atrioventricular valve regurgitation, increased pulmonary venous return, atrial hypertrophy, pulmonary venous obstruction and the consequences of chronic systemic venous hypertension, including hepatic congestion and dysfunction [11].

Other complications include atrial thrombus formation with an increased risk of systemic embolism, and the development of pulmonary and systemic arteriovenous malformations [12]. In patients with complex congenital heart disease, thromboembolic complications result from several mechanisms [12]. These can include paradoxical embolisms, where right-left shunts allow blood clots to pass from the venous circulation into the arterial circulation, including the splenic artery. This may be due to rhythm disorders such as AF, which is common in adults with congenital heart disease and promotes thrombogenesis. It may involve pulmonary hypertension and blood hyperviscosity.

CONCLUSION

Splenic infarction is a potentially serious thromboembolic complication in complex congenital heart disease. In addition to demonstrating the possibility of late discovery of these cardiopathies in adulthood, this observation illustrates one of the major complications. Improved awareness would enable early diagnosis of these conditions at an operable stage.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Wendlassida Martin NACANABO: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Visualization; Writing – original draft.

Taryètba André Arthur SEGHDA: Visualization; Writing – review & editing

Mohamed MAMA SIKA: Writing – review & editing

Anna Tall/Thiam: Supervision

Nobila Valentin Yameogo: Supervision André K. Samadoulougou: Supervision Patrice Zabsonre: Supervision

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable Request.

CONSENT

We have obtained the patient’s consent for publication. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the journal’s patient consent policy.

REFERENCES

- Lawrence YR, Pokroy R, Berlowitz D, Aharoni D, Hain D, Breuer GS. Splenic infarction: an update on William Osler’s observations. Isr Med Assoc J. 2010; 12: 362-365.

- Karsenty C, Waldmann V, Mulder B, Hascoet S, Ladouceur M. Thromboembolic complications in adult congenital heart disease : the knowns and the unknowns. Clin Res Cardiol. 2021; 110: 1380- 1391.

- van der Linde D, Konings EEM, Slager MA, Witsenburg M, Helbing WA, Takkenberg JJM, et al. Birth Prevalence of Congenital Heart Disease Worldwide (Prévalence à la naissance des cardiopathies congénitales dans le monde): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 58: 2241-2247.

- Peoples WM, Moller JH, Edwards JE. Polysplénie: A review of 146 cases. Pediatr Cardiol. 1983; 4: 129-137.

- Moodie DS. Adult Congenital Heart Disease. Ochsner J. 2002; 4: 221-226.

- Zühlke L, Mirabel M, Marijon E. Cardiopathies congénitales et maladies cardiaques rhumatismales en Afrique: progrès récents et priorités actuelles. Heart. 2013; 99:1554-1561.

- Webb GD. Challenges in the care of adult patients with congenital heart defects (Défis dans la prise en charge des patients adultes atteints de malformations cardiaques congénitales). Heart. 2003; 89:465-469.

- Ba Ngouala GAB, Affangla DA, Leye M, Kane A. Prévalence des cardiopathies infantiles symptomatiques au Centre Hospitalier Régional de Louga, Sénégal. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2015; 26: e1-5.

- Hoffman JIE, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002; 39: 1890-1900.

- Fontan F, Kirklin JW, Fernandez G, Costa F, Naftel DC, Tritto F, et al. Outcome after a « perfect » Fontan operation. Circulation. 1990; 81: 1520-1536.

- Khairy P, Fernandes SM, Mayer JE, Triedman JK, Walsh EP, Lock JE, et al. Long-Term Survival, Modes of Death, and Predictors of Mortality in Patients With Fontan Surgery (Survie à long terme, modes de décès et facteurs prédictifs de mortalité chez les patients ayant subi une chirurgie de Fontan). Circulation. 2008; 117: 85-92.

- Baumgartner H, Bonhoeffer P, De Groot NMS, de Haan F, Deanfield JE, Galie N, et al. Task Force on the Management of Grown-up Congenital Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), Association for European Paediatric Cardiology (AEPC), ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). Lignes directrices de l’ESC pour la prise en charge des cardiopathies congénitales de l’adulte (nouvelle version 2010). Eur Heart J. 2010; 31: 2915-2957.