Management and Clinical Outcome of Severe Diabetic Ketoacidosis (pH < 7.0) In Children and Adolescents

- 1. Department of Pediatrics, Division of General Pediatrics, University of Heidelberg, Germany

- 2. Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Cardiology, University of Heidelberg, Germany

Abstract

Objective: Evaluation of the management and clinical outcome of children and adolescents with severe diabetic ketoacidosis.

Methods: Patients admitted to the University Children´s Hospital Heidelberg with initial blood pH ≤ 7.0 were included in the study. Blood gas analyses, blood glucose and electrolytes were measured within the first 24 hours. The neurological status was evaluated by Glasgow coma scale (GCS). Requirements for insulin, fluid and potassium were recorded.

Results: 13 patients (mean 12.0±4.62 years) with blood pH≤7.0 were identified. Six were admitted with onset of type 1 diabetes. 77 % displayed mental alterations (GCS≤12/15). Mean insulin dose within the first hours was 0.09 IU/kg/h, blood glucose declined by 66 mg/dl/h within the first 4 hours. Blood pH reached normal levels after 16 hours, while base deficits lasted for more than 24 hours. High doses of potassium were required (range: 0.02-0.60 mmol/kg/h) within the first 24 hours. No sodium bicarbonate was administered. None of the patients developed severe neurological complications.

Conclusion: Treatment of severe diabetic ketoacidosis according to the international guidelines is safe and successful in routine clinical settings. There is no need for bicarbonate even in patients with initial pH ≤ 7.0

Keywords

Childhood diabetes; Diabetes mellitus Type 1; Ketoacidosis management

CITATION

Weiland C, Meyburg J, Springer W, Bettendorf M, Haas D, et al. (2018) Management and Clinical Outcome of Severe Diabetic Ketoacidosis (pH < 7.0) In Children and Adolescents. JSM Diabetol Manag 3(1): 1005

ABBREVIATIONS

DKA: Diabetic Ketoacidosis; GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale; ISPAD: International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetology; SD: Standard Deviation

INTRODUCTION

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is one of the major acute complications of diabetes mellitus type 1 (T1DM) in childhood associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality [1-5]. The frequency of diabetic ketoacidosis ranges from 15-70% at onset of T1DM and from 1-10% in children with established T1DM [6]. In Germany, diabetic ketoacidosis is present in approximately 21% of children and adolescents at onset of T1DM [7]. The risk for DKA is associated with young age, poor metabolic control, and socioeconomic status. DKA has still considerable mortality rates even in Europe and North America [5,8,9]. Cerebral edema is the most common cause for mortality in DKA [10]. In a casecontrol study by Glaser et al. it was shown that, although cerebral edema was present in some patients on admission to the hospital, it developed in most patients 3 to 13 hours after initiation of therapy for DKA, suggesting that the treatment itself might contribute to the development of cerebral edema [11]. The risk for cerebral edema is correlated with the severity of acidosis and with the use of sodium bicarbonate during initial treatment [12].

The first consensus guidelines for the management of ketoacidosis in children and adolescents were published by the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) in 1995 and were updated several times [13]. The ISPAD guidelines involve low-dose insulin administration as well as fluid and electrolyte repletion at a slow rate. Other guidelines and recommendations follow the same principles [14,15]. Studies have shown that bicarbonate therapy in the management of DKA did not have measurably beneficial effects in the recovery outcome [16,17]. On the contrary, it may increase hepatic ketone production, which slows the rate of recovery from ketosis [18]. One of the strongest arguments against the bicarbonate therapy is the concern about cerebral edema, which may arise from a paradoxical CNS acidosis [19]. In accordance with these studies the ISPAD guidelines have not recommended the use of bicarbonate administration in the therapy of diabetic ketoacidosis. However, depression of conscious level in children with DKA is closely related to low blood pH, and therefore even the latest update of the ISPAD guidelines suggest considering the use of bicarbonate in patients with severe acidosis. Furthermore,pediatric diabetologists frequently get into debate on the use of bicarbonate with physicians on intensive care units (ICU), when diabetic patients with initial pH < 7.00 are admitted.

The purpose of the present investigation was a) to evaluate if patients with very severe DKA and profound acidotic disturbances benefit from the therapeutic management following the consensus guidelines of the ISPAD, and b) to analyze the insulin, potassium, and fluid requirements as well as the course of laboratory parameters within the first 24 hours of treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Children and adolescents admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit at the University Children´s Hospital Heidelberg for severe DKA with initial blood pH levels+7.00 in the years 2003- 2015 were included.

Diagnosis of DKA followed the criteria of the ISPAD. Blood samples were taken on admission for clinical chemistry and full blood count. An acid-base status was assessed by capillary blood gas analysis. Urine ketones were measured by reflection photometry (Clinitek Atlas® and Clinitek 500® from Bayer / Siemens, Germany) with a detection limit of 15 mg/dl.

Patients were treated according to a written in-house protocol which followed the ISPAD consensus guidelines 2000 and its updates:

a) Fluid replacement: Intravenous fluid substitution was started with normal saline solution (NaCl 0.9 %). When blood glucose level fell below 250 mg/dl, it was changed to halfelectrolyte solution (NaCl 0.45 % / Glucose 5 %).

b) Insulin administration: A dilution of regular insulin was administered intravenously at 1 IU/ml by an infusion pump. The initial substitution dose varied between 0.05 and 0.1 IU/ kg/h. A reduction in blood glucose between 50 and 100 mg/ dl/h was achieved by adapting insulin and fluid infusion rates. Intravenous insulin application was switched to subcutaneous insulin application once ketoacidosis resolved (pH ≥ 7.3) and the patients returned to a stable clinical condition.

c) Potassium replacement: Potassium was administered from the beginning of insulin treatment when oliguria and hyperkalemia were excluded. We started an overall substitution of 2 to 3 mmol/kg/24h. Potassium substitution was administered continuously by a separate infusion pump, which allowed adjustment of replacement independently of the fluid replacement. The substitution dose was adjusted hourly depending on the serum potassium levels.

d) Correction of acidosis: Correction of acidosis was performed by substitution of insulin and fluid alone. The use of sodium bicarbonate was considered only in case of decreased cardiac contractility or life-threatening hyperkalemia. The blood pH level did not serve as criteria for the use of bicarbonate.

e) Monitoring: Vital signs and ECG were monitored continuously. Capillary blood gases as well as blood glucose and electrolytes were initially checked every hour.

Statistical analysis and figures were performed using Microsoft Office Excel 2003 and SSPS Statistics 17.0. Results are shown as means + standard deviation (SD).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The study group included 13 children and adolescents (8 boys and 5 girls) with a mean age of 12 years (12.00 ± 4.62). In 46 % (n=6) DKA occurred at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. In the subgroup of patients with previously diagnosed T1DM (n=7),inadequate dosage of insulin and inadequate frequency of blood glucose self-monitoring due to non-compliance were identified as the causes of DKA in most of the patients. One patient developed ketoacidosis due to non adjustment of insulin doses to higher requirements during an infection of the respiratory tract. Two patients had experienced DKA once before.

Clinical findings: On admission, 11 out of 13 patients (84 %) showed signs of moderate to severe dehydration (dry skin and mucosa, reduced skin turgor, and tachycardia). An estimated extracellular fluid deficit of 5 to 10 % of body weight was detected in all of these patients. 92 % (n=12) presented with tachypnea and ´Kussmaul respiration`. Gastrointestinal complaints (abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting) were present in 69 % (n=9) of the patients. Additionally, 10 patients (77 %) displayed mental alterations (Glasgow-Coma-Scale (GCS) + 12/15). Typical clinical findings were fatigue, drowsiness and clouding of consciousness. One patient presented with shock on admission (blood pressure: 67/38 mmHg, heart rate: 114 bpm). He required rapid i.v. fluid substitution (20 ml/kg/h) and norepinephrine for 14 hours.

Laboratory: In the first blood samples taken from the patients on admission, an average capillary blood pH level of 6.93±0.07 was detected. The lowest pH level (6.79) was found in a 13-year-old girl, who arrived in hospital with a severely depressed sensorium (GCS = 7/15). Patients´ mean base excess on admission was –26.85 ± 1.99 mmol/l and the blood glucose level ranged from 379 to 1259 mg/dl with a mean of 609 ± 253 mg/dl. All patients showed a moderate to severe leucocytosis (27.47 ± 10.20 /nl). Leucocytosis is a frequent finding in patients with DKA, butit is not associated with infection (31, 32). Leucocytosis in these patients may be induced by stress hormones or dehydration.

Interestingly, the highest white blood count was found in a patient who presented in a bad clinical condition with signs of severe dehydration and greatly depressed consciousness (GCS = 7/15).

High urinary ketones were registered in all 13 patients on admission.

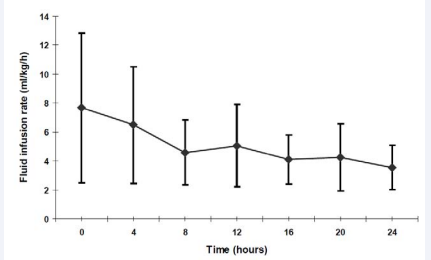

Treatment: Volume replacement was started at an average rate of 7.7 ± 5.1 ml/kg/h. As expected, intravenous fluid requirements showed a decline within the first 8 hours with intravenous fluid administration being decreased to an average of 5.1 ± 2.9 ml/kg/h after 12 hours and reaching a stable rate of 3.6 ± 1.5 ml/kg/h at the end of the observed 24 hours (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Intravenous Fluid substitution (ml/kg/h) within the first 24 hours Data are shown as mean + standard deviation (SD)

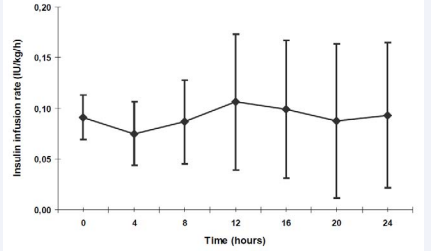

Average insulin substitution in the first hour was 0.09 IU/ kg/h. The insulin doses were adapted individually according to the blood glucose levels measured every hour. Within the first 24 hours, the insulin substitution dose varied only little (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Intravenous low-dose Insulin substitution (IU/kg/h) within the first 24 hours Data are shown as mean + standard deviation (SD).

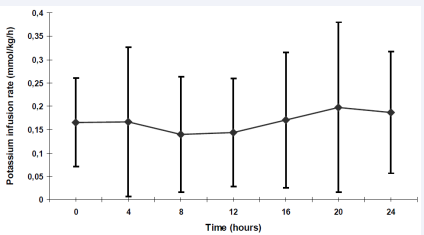

Potassium was administered from the beginning of the therapy in all but two patients. These two patients presented with anuria and hyperkalemia on admission. Similar to the substitution of insulin and fluid, potassium adjustments were performed according to laboratory data. During the first 4 hours the average potassium infusion rate was 0.09mmol/kg/h. Within the following hours of the treatment, the infusion rates needed to be raised to 0.14 mmol/kg/h (9th to 12th after beginning of treatment) and reached a maximum of 0.20 ± 0.18 mmol/kg/h in the 17th to 20th hour of the treatment (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Potassium substitution (mmol/kg/h) within the first 24 hours Data are shown as mean + standard deviation (SD)

Large intra- and inter-individual variations in the potassium requirement within the first 24 hours of treatment were observed (range: 0.02-0.6 mmol/kg body weight/hour). The plasma potassium levels were kept between 3 and 5 mmol/l.

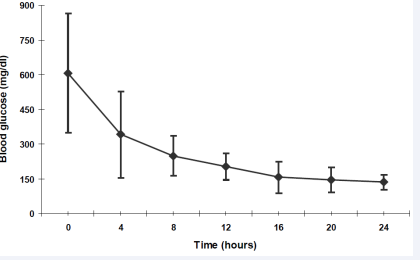

Blood glucose showed a slow but continuous fall with an average decline rate of 66 mg/dl/h within the first 4 hours, followed by 23 mg/dl/h in the 5th to 12th hour. From the 13th to 16th hour, the rate of fall in blood glucose decreased to 11 mg/ dl/h. In the following 8 hours (17th to 24th), blood glucose finally reached normal values with only minor changes (figure 4).

Figure 4 Blood glucose (mg/dl) within the first 24 hours. Data are shown as mean + standard deviation (SD)

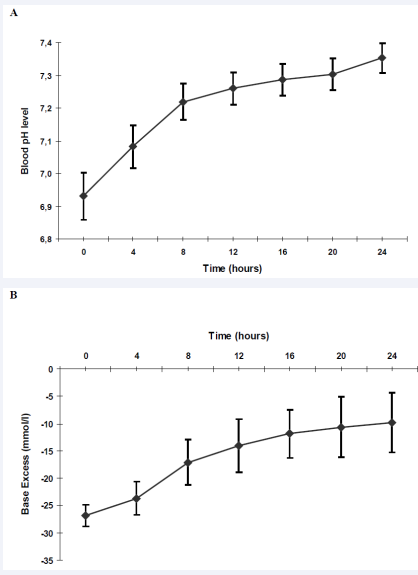

The time courses of blood pH and base excess are shown in Figure 5A and 5B,

Figure 5

A Capillary blood pH levels within the first 24 hours.

B Capillary Base Excess (mmol/l) within the first 24 hours. Data are shown as mean + standard deviation (SD).

respectively. While base excess did not reach normal values after 24 hours of intensive treatment, blood pH level (7.35 ± 0.05) and blood glucose (136 ± 32 mg/dl) returned to normal ranges

Patients stayed in the ICU for an average of 25.2 ± 19.3 hours. When patients were clinically in a stable condition with normal sensorium, they were transferred to a regular ward. At this point of time, laboratory parameters, especially the acidosis, had not completely returned to normal values in most of the patients (BE –9.78 ± 5.43).

In this observational clinical study, the feasibility of the ISPAD guidelines and clinical outcome of patients with most severe diabetic ketoacidosis were evaluated. A detailed inhouse protocol guided by the ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines was used. All patients were successfully treated according to this protocol. The principles of management of DKA included adequate but cautious fluid replacement, continuous low-dose insulin substitution, electrolyte substitution and intensive and careful monitoring of laboratory parameters as well as repeated evaluation of clinical and neurological (GCS) status.

Fluid replacement in DKA follows the same principles as in dehydration or shock: an initial phase of great demand of fluids, followed by a phase of slower rehydration and replacement of losses [14]. This principle of fluid replacement was safe and was well tolerated by all patients. Input and output of fluids were recorded continuously, and fluid balance was calculated every six hours. Previous studies have suggested an association between cerebral edema and a) administration of large amounts of fluids and b) the time in which these fluids were applied [11,16, 20]. The use of lower infusion rates has been proven safe in children [21,22].

In DKA, the extent of hyperglycemia is mainly determined by hepatic glucose production. This mechanism is effectively interrupted by insulin substitution, which suppresses hepatic glucose production [23,24]. Since 1976 a variety of studies have clearly demonstrated that continuous low dose insulin treatment in patients with DKA resulted in a slow but steady reduction of hyperglycemias well as a gentle normalization of acidosis by avoiding further aggravation of electrolyte displacement [22,25- 27]. Physiological studies suggest that with insulin administered intravenously at a rate of 0.1 IU/kg/h, a stable plasma insulin level of around 100 - 200 µU/ml can be achieved within 60 minutes. Such plasma insulin levels are able inhibiting lipolysis and ketogenesis [23]. In accordance with the common recommendations, patients in the present study were administered an average of 0.08 – 0.11 IU/kg/h insulin intravenously by a continuous infusion pump whereby blood glucose levels showed a continuously but slowly decline. More recent data show that children can also be managed safely with initial insulin doses as low as 0.03 - 0.05 IU/kg/h,

avoiding a too rapid fall in blood glucose levels [28]. In a study from 2009, Puttha et al. show the effectiveness and safety of low (0.05 IU/kg/h) compared with standard dose insulin infusion (0.1 IU/kg/h) in correcting the main biochemical abnormalities associated with DKA in a pediatric population within the first 6 hours after starting treatment [29].

Common problems during the treatment of DKA are electrolyte disturbances. Especially the first few hours of therapy are typically associated with a rapid decline in the plasma potassium concentration. This decrease is caused by several factors, the most significant being the insulin-mediated re-entry of potassium into the intracellular compartment. As the treatment will rapidly decrease plasma potassium concentrations, potassium replacement must be initiated as soon as possible. Interestingly, potassium substitution required by our patients was not high on admission, but it showed a continuous increases in the course of time, finally reaching a maximum in the second half of the first 24 hours of treatment (17th to 20th hour). This observation is in accordance with a study by Vanelli et al. who demonstrated that as soon as blood glucose drops below 250 mg/dl, the requirement of potassium increases because of progressively increased endocellular uptake [30].

Bicarbonate therapy in DKA still remains controversial, although most pediatric centers do not use it. However, a recent study demonstrated that the adherence to pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis protocols is still poor [33]. In several controlled trials the use of sodium bicarbonate in children and adults with diabetic ketoacidosis has not been able to show any immediate clinical benefits or measureable beneficial effects in the recovery outcome, even in patients with severe acidosis [19,34]. Sodium bicarbonate may even cause increased intracellular acidosis due to excess carbon dioxide production, paradoxical acidosis in the central nervous system leading to cerebral edema [18]. The present study suggests that children and adolescents with pH < 7.00 do not need bicarbonate.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the present study provides evidence that the international guidelines for the treatment of children and adolescents with ketoacisosis can be applied to children and adolescents with even severe diabetic ketoacidosis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank the staff of our intensive care units for supporting this study.

REFERENCES

11.Glaser N. Cerebral Edema in Children with Diabetic Ketoacidosis. Curr Diab Rep. 2001; 1: 41-46.

27.Burger W, Weber B. Treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis in children and adolescents. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 1983; 131: 694-701.