Estrogen Promotes Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation by Upregulating P2X7R-Related CREB Phosphorylatio

- #. Equal contribution

- 1. Department of Physiology, Second Military Medical University, China

- 2. Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Changhai Hospital, China

Abstract

Recent evidence suggests a role for the P2X7 purinergic receptor (P2X7R) in cell proliferation, but the underlying mechanisms of its effects on estrogen related breast cancer are unclear. Here, we examined the role of P2X7R in estrogen-induced proliferation and the underlying mechanisms regulating estrogen modulation of P2X7R in the breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231, using MTT assays, qRT-PCR, western blotting analysis and siRNA transfection. In MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, benzo ATP (BzATP) significantly promoted cell proliferation, which was blocked by the P2X7R antagonist A438079. In MCF-7 cells, the promoting effect of estrogen was blocked by the nonselective purinergic receptor antagonist PPADS, A438079 or P2X7R siRNA. Estrogen upregulated P2X7R expression at both the mRNA and protein levels, which was blocked by the estrogen receptor (ER) antagonist ICI 182,780, ERβ antagonist MPP or ERα siRNA, but not by ERβ antagonist PHTPP. The selective ERα agonist PPT, but not ERβ agonist DPN, significantly increased P2X7R expression. Estrogen and PPT significantly increased expression of ERK1/2 and Akt expression, which was blocked by ICI 182,780. Antagonists against MAPK (U0126) and PI3k/Akt (LY294002) blocked the estrogen effect on P2X7R expression and phosphorylation of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB). Administration of three different P2X7R antagonists or silencing P2X7R in MCF-7 cells injected in nude mice reduced MCF-7-derived tumor growth and decreased vessel formation. These findings suggested that estrogen promoted breast cancer cell proliferation by upregulating P2X7R via ERβ through the ERK1/2 or Akt-pCREB signaling pathways.

Keywords

• Estrogen

• P2X7R

• MCF-7 cells

• CREB

• Phosphorylation

Citation

Yu LH, Wang LY, Li HJ, Qu HN, Ma B, et al. (2025) Estrogen Promotes Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation by Upregulating P2X7R-Related CREB Phosphorylation. J Cancer Biol Res 12(1): 1153.

ABBREVIATIONS

17β-E2: 17β-estradiol; Akt: Protein Kinase B; ATP: Adenosine Triphosphate; BzATP: benzo ATP; ER: Estrogen Receptor; ERα: Estrogen Receptor alpha; ERβ: Estrogen Receptor beta; ERK 1/2: Extracellular Signal Regulated Kinase 1/2; MAPK: Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase; MPP: Methyl-piperidino-pyrazole; P2X7R: P2X7 Receptor; PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; PI3K: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; siRNA: Small Interfering RNA.

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is one of the most common malignancies in women. The incidence of breast cancer has been increasing over the past several decades [1]. Estrogen plays a critical role in the progression of breast cancer. Evidence has shown that 17β-estradiol induces neoplastic transformation in human breast cancer cells [2], promotes the growth of breast cancer cells in vivo and in vitro [3] and significantly increases the risk of breast cancer [4]. Previous studies have indicated that the two nuclear estrogen receptors ERα and ERβ respond differently to estrogen and thus play different roles in the process of proliferation. ERα appears to promote proliferation while ERβ mainly suppresses the proliferation of tumor cells [5,6].

P2 nucleotide receptors are a family of purinergic receptors on cell membranes [7]. These receptors are classified as P2X (cation channels) and P2Y (G-protein coupled) receptors. The P2X7 receptor (P2X7R) is a member of the P2X receptor subfamily that functions as a ligand-operated channel permeable to K+, Na+, and Ca2+. Upon prolonged agonist exposure, P2X7R leads to the formation of progressively enlarged cytolytic pores (~900 Da) on the cell surface which may induce intrinsic cell death programs [8]. However, P2X7R has recently been shown to possess under physiological conditions survival/growth-promoting effects in several primary cell types including mouse embryonic stem cells, neural progenitor cells, microglial cells, osteoblasts and CD8+ memory T cells [9-14]. Moreover, P2X7R expression has been shown to be increased in several malignant tumors such as prostate cancer, breast carcinoma, neuroblastoma, leukemia and thyroid papillary carcinoma [15]. Recent in vitro and in vivo evidence has shown that P2X7R plays a central role in carcinogenesis enhancing tumor cell growth [16-19], tumor-associated angiogenesis [15] and cancer invasiveness [20-22], whereas P2X7R blockade inhibits tumor growth in melanoma [23], mesothelioma [24], glioma [25], osteosarcoma [26], and myeloid leukemia [27]. These experiments suggest that P2X7R antagonists may be novel potential anticancer drugs. Furthermore, P2X7R was shown to be overexpressed in breast cancer tissues and positively associated with ER expression [28]. However, whether P2X7R is involved in the estrogen effect on breast cancer cell proliferation is unknown and the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood. Therefore, in the current study we investigated the effects of P2X7R on the breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231, examined the involvement of P2X7R in the estrogen effect on proliferation of MCF-7 cells, and explored possible pathways of estrogen modulation of P2X7R.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and transfection

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines were maintained in DMEM (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sijiqing, Hangzhou, China). The cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. At 24 h prior to the drug experiments, the culture medium was replaced with a steroid-free medium (phenol red-deficient DMEM containing 8% heat inactivated FBS that was previously treated with charcoal to remove steroids). MCF-7 cells silenced with hP2X7 specific shRNA or MCF-7 P2X7R negative control cell clones were obtained by transfection with predesigned shRNA obtained from Genepharma (Shanghai, China) targeting the following sequences: GCATGAATTATGGCACCAT (shRNA1); GCAGACTACACCTTCCCTT (shRNA2); and TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT (shRNA negative control). Stably transfected MCF-7 cells expressing P2X7R shRNA1 and P2X7R shRNA2 were obtained by selection with puromycin (2 μg/mL). The cell lines were tested by Shanghai Biowing Applied Biotechnology Co., (Shanghai, China) using STR genotyping.

Cell viability assays

Cell suspensions were seeded in 96-well plates for 12 h to allow for attachment and then were treated with different concentrations of drugs. Drug-treated cells were incubated for 48 h and then 5 mg/mL MTT solution was added to the cultures for an additional 4 h. Finally, the medium containing MTT was removed and 100 μL DMSO solution was added. As a result, living cells formed crystals due to the presence of MTT, which were dissolved in the DMSO. Absorbance was then measured at 490 nm by an immunosorbent microplate reader.

RT-PCR and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted by TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Total RNA (2 µg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA with oligo (dT)15 primers in a 25 µL reaction using SuperScriptTM reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitative real time PCR was carried out using the Rotor-Gene 3000 thermal cycler (Corbett Research, Sydney, Australia). The reaction solution consisted of 2.0 μL diluted cDNA, 0.2 μM of each paired primer and 2× Taq PCR master mix (Tiangen, Beijing, China). All samples were normalized against an internal β-actin control. The following primers were used: P2X7R, 5’-AGATCGTGGAGAATGGAGTG-3’ (forward) and 5’-TTCTCGTGGTGTAGTTGTGG-3’ (reverse); β-actin, 5’-GTGGGGCGCCCCAGGCACCA-3’ (forward) and 5’-CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGATTTC-3’ (reverse). SYBR Green was used as detection dye. Reaction conditions consisted of a denaturation step at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of amplification at 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s and 72°C for 10 s. The temperature range to detect the melting temperature of the PCR product was set from 60°C to 95°C. The comparative Ct (threshold cycle) method with arithmetic formula (2-??Ct) was used to determine the relative quantitation of gene expression for both target and housekeeping genes.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) of ERα and ERβ

The siRNAs for ERα and ERβ were designed and synthesized by GenePharma. Control siRNA was scrambled sequence without any specific target. The target sequences for ERα were 5’-CAGGCCAAAUUCAGAUAAUTT-3’ (sense) and 5’-AUUAUCUGAAUUUGGCCUGTT-3’ (antisense). The target sequences for ERβ were 5’-GCCCUGCUGUGAUGAAUUATT-3’ (sense) and 5’-UAAUUCAUCACAGCAGGGCTT-3’ (antisense). Scrambled siRNA duplexes were designed (5’-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3’ and 5’-ACGUGA CACGUUCGGAGAATT-3’) for use as a negative control (NC). MCF-7 cells were transfected with 25 nM target siRNA or NC siRNA using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and transfections were carried out for 18 h (for ERα) and 24 h (for ERβ). Subsequently, the culture medium was replaced with phenol red-deficient DMEM-Ham’s F-12 medium supplemented with 8% heat-inactivated FBS containing 17β-E2 (0.1 μmol/L). After 48 h, MTT assays or western blot analyses were conducted to assess cell viability or P2X7R protein expression.

Western blotting analysis

Cells were harvested and homogenized in cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% deoxycholic acid sodium salt, 0.1% SDS, and a protease inhibitor mixture) using a homogenizer. Total protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method using bovine serum albumin as a standard. Equal amounts of protein were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blockade in blocking buffer consisting of 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 137 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat milk for 2 h at room temperature, membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against P2X7R (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), ERα or ERβ (1:500, Santa Cruz), ERK1/2 or Akt (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB; 1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology) or β-actin (1:8,000, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The membranes were washed for 5 min each with TBST, incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1,000, Santa Cruz) for 2 h at room temperature, and finally visualized in ECL solution. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence western blotting detection system (Amersham Imager 600, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). The chemiluminescence signals were quantified with a GeneGnome XRQ scanner using GeneTools software (SynGene, Frederick, MD, USA). The ratio of band intensities to β-actin was obtained to quantify the relative protein expression level.

Mouse xenograft and in vivo drug administration

In vivo experiments were performed using 4–5-week old female BALB/c mice, which were provided by Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co., LTD (Shanghai, China). All animals were kept in a pathogen-free environment and fed ad libitum. The procedures for care and use of animals were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Naval Medical University and all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of animals were followed. Mice were pretreated with 3-mm pellets containing 17β-E2 (0.72 mg/60-day release; Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL, USA) by subcutaneous injection, starting 2 weeks before cell implantation. To induce tumor formation, 5×106 MCF-7 cells or MCF-7 cells silenced with hP2X7-specific shRNA were subcutaneously inoculated into BALB/c mice. Tumor size was measured with a caliper and volume was calculated according to the following equation: volume = π/6 (w1 × w22), where w1 = major diameter and w2 = minor diameter [15].

Histology

Tumors were fixed in 20% formalin for 24 h, processed and embedded in paraffin. Five-µm thick sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). For immunohistochemistry of CD31, sections were incubated with anti-CD31 primary antibody for 24 h. All images were acquired and analyzed with a Nikon Eclipse 90i digital microscope equipped with NIS-elements software (Nikon Instruments Europe, Amsterdam, Netherlands). The vascular network was evaluated by counting the number of blood vessels per microscope field with a 20× objective. Data shown represent counts from three different sections from each tumor. Fifteen fields, in the center and periphery of the mass, were analyzed for each tumor.

Statistical analysis

All data in the text and figures are shown as means ± S.E.M. Experiments were independently performed three times. Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA, followed by Student-Newman Keuls tests for multiple comparisons. Results from the immunohistochemical experiments were analyzed using chi-squared tests. The p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

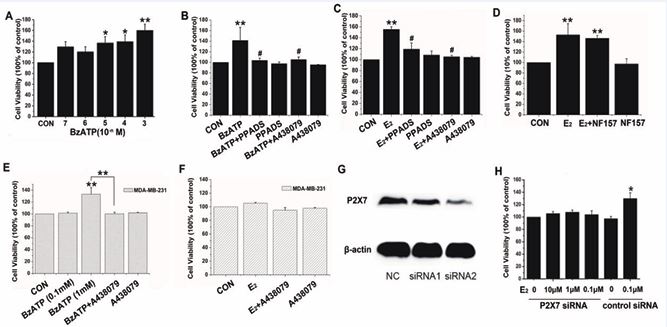

BzATP promoted the proliferation of MCF-7 cells via P2X7R.

In order to validate the effect of P2X7R on MCF-7 cells, we carried out MTT assays to measure cell viability. The MTT results showed that 48 h after application of the P2X7R agonist BzATP (10 µmol/L–1 mmol/L), the proliferation of MCF-7 cells was increased significantly compared with the control groups in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1A, n=3). After co-application of BzATP (0.1 mmol/L) with the nonselective P2X receptor antagonist PPADS (1 µmol/L) or the selective P2X7R antagonist A438079 (10 µmol/L), the increase in proliferation caused by BzATP was reversed (Figure 1B, n=6, p < 0.01). In parallel with the MCF-7 cells, BzATP at a concentration of 1 mmol/L also increased the proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 1E, n=3, p < 0.01). After co-application of BzATP and A438079, the proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells returned to control levels (Figure 1E, n=3, p < 0.01).

Figure 1 The effects of P2X7R on MCF-7 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells. A) BzATP promoted MCF-7 in a dose-dependent manner. B) P2X7R antagonists blocked the BzATP effect. C) P2X7R antagonists blocked 17β-E2 on MCF-7. D) The excitatory effect of estrogen was not blocked by NF 157. E) BzATP at a high concentration promoted MDA-MB-231, which was blocked by A438079. F) A438079 did not block the estrogen effect on MDA-MB-231. G) Reduced P2X7R expression in MCF-7. H) Silencing P2X7R significantly reduced the estrogen-promoted proliferation. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 vs control group; #p < 0.01 vs BzATP or E2 group.

P2X7R was involved in the process of estrogen promoting proliferation of MCF-7 cells.

From our previous study [29], we found that 17β E2 in different concentrations (0.01 nmol/L–1 μmol/L) promoted the proliferation of MCF-7 cells via ERα receptors. To investigate whether P2X7R was involved in the effect of 17β-E2 on cell proliferation, we applied PPADS (1 μmol/L) or A438079 (10 μmol/L) to block the function of P2X7R and then examined the effect of 17β-E2 on the proliferation of MCF-7 cells. The MTT results showed that the proliferation of MCF-7 cells was increased significantly after application of 17β-E2 (0.1 μmol/L, 48 h treatment), which was blocked by PPADS or A438079 (Figure 1C, n=3, p < 0.01). However, A438079 did not affect the estrogen effect on the MDA-MB-231 cell line (Figure 1F, n=3, p > 0.05). Because BzATP can also activate P2Y11 receptors, we treated the cells with the P2Y11 receptor antagonist NF 157 and then studied the effect of 17β-E2 on the proliferation of MCF-7 cells. The MTT results showed that the excitatory effect of estrogen could not be blocked by NF 157 (Figure 1D, n=3, p > 0.05). We then tested the tumorigenic capacity of MCF-7 cells silenced with hP2X7 specific siRNA. As shown in Figure 1G and H, silencing significantly reduced the estrogen-promoted proliferative response. These data confirmed that P2X7R was involved in the process of estrogen promoting the proliferation of MCF-7 cells.

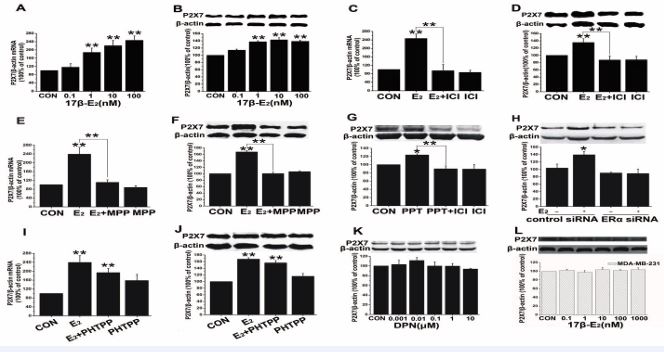

Estrogen upregulated the expression of P2X7R via ERα in MCF-7 cells.

In order to explore the possible effect of estrogen on P2X7R expression, we examined P2X7R expression in MCF-7 cells after treatment with estrogen by qRT-PCR and western blot methods. In MCF-7 cells, after 48 h incubation with 17β-E2 (1 nmol/L–0.1 μmol/L), P2X7R mRNA levels were significantly increased compared with those of the control groups (Figure 2A, n=3, p < 0.01), as were the P2X7R protein levels (Figure 2B, n=3, p < 0.01). The excitatory effect of 17β-E2 on P2X7R expression was blocked by the ER antagonist ICI 182,780 (1 µmol/L) at both the mRNA (Figure 2C, n=3, p < 0.01) and protein levels (Figure 2D, n=3, p < 0.01). To prove that the effect of estrogen was specific to ERs, further research was conducted with the ERα antagonist MPP and the ERβ antagonist PHTPP in MCF-7 cells after 48 h treatment with 17β-E2 (0.1 μmol/L).

Figure 2 17β-E2 on the expression of the P2X7R in MCF-7 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells. A-F) 17β-E2 stimulation of P2X7R mRNA or protein expression was blocked by the ICI or MPP. G, K) PPT could mimic the effect of estrogen, while DPN had no effect. H) ERα siRNA blocked the upregulation of P2X7R protein expression by 17β-E2 . I, J) Estrogen-induced upregulation of P2X7R mRNA or protein levels was not blocked by the PHTPP. L) 17β-E2 did not affect the expression of P2X7R in MDA-MB-231. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 vs control group.

The expression of P2X7R was stimulated by17β-E2 at both the mRNA (Figure 2E, n=5, p < 0.01) and protein levels (Figure 2F, n=3, p < 0.01). In addition, ERα agonist PPT (0.1 μmol/L) could mimic the effect of estrogen (Figure 2G, n=3, p < 0.05). Furthermore, after depleting ERα by siRNA, 17β-E2 (0.1 μmol/L) had no effect on P2X7R protein levels (Figure 2H, n=3, p > 0.05). However, PHTPP did not block the promoting effect of 17β-E2 on the expression of P2X7R. After pre-incubation with PHTPP and 17β-E2 , the expression of both P2X7R mRNA (Figure 2I, n=3, p > 0.05) and P2X7R protein (Figure 2J, n=3, p > 0.05) was not significantly different compared with 17β-E2 treatment alone. The expression of P2X7R protein was also not affected by ERβ agonist DPN (1 nmol/L–0.1 μmol/L; Figure. 2K, n=3, p > 0.05). In the ERα-negative cell line MDA-MB-231, 17β-E2 (0.1 nmol/L–1 μmol/L) did not affect the expression of P2X7R (Figure 2L, n=3, p >0.05 vs control at each concentration).

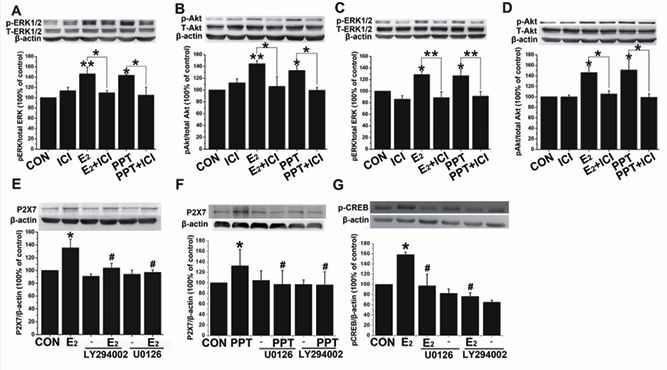

MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt signaling were responsible for estrogen-induced P2X7R expression.

It has been reported that estrogen exerts proliferative effects mediated by rapid membrane-starting actions. Estrogen via binding to ERs can activate classical, genomic pathways, which directly regulate nuclear transcription. On the other hand, estrogen binding to ERs may also switch on non-classical, rapid estrogen pathways involving alterations in transcription factor and second messenger functions. Furthermore, a variety of kinase signaling pathways have been shown to be activated by estrogen, including mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) [30,31], and phosphatidylinositide 3,4,5-trisphosphate kinase (PI3K)/Akt [32]. To determine whether estrogen acutely activated kinase signaling pathways we then promotes expression of P2X7R in MCF-7 cells, we exposed these cells to 17β-E2 (0.1 μmol/L) and PPT (0.1 μmol/L) for 15 min and 4 h, respectively, and measured levels of phosphorylated Akt and ERK. Western blot analysis demonstrated that in MCF-7 cells 17β-E2 or PPT treatment significantly increased expression levels of phospho-ERK and phospho-Akt after 15 min (Figure 3A, n=3, p < 0.05; Figure 3B, n=3, p < 0.05) and 4 h (Figure 3C, n=3, p < 0.05; Figure 3D, n=3, p < 0.05). These effects could be reversed by ICI 182,780 (1 μmol/L, Figure 3A, n=3, p < 0.05; Figure 3B, n=3, p < 0.01; Figure 3C, n=3, p < 0.05; Figure 3D, n=3, p < 0.05).Then we sought to determine whether the excitatory effect of 17β-E2 on P2X7R expression was associated with kinase signaling pathways. MCF-7 cells were pretreated with MAPK antagonist U0126 (0.1 μmol/L) and PI3k/Akt antagonist LY294002 (0.1 μmol/L) for 2 h, followed by a 48 h co-treatment with 17β-E2 (0.1 μmol/L) or PPT (0.1 μmol/L). Western blot analysis demonstrated that in MCF 7 cells 17β-E2 (Figure 3E, n=3, p < 0.05) or PPT (Figure 3F, n=3, p < 0.05) treatment significantly increased expression levels of P2X7R, which could be blocked by U0126 or LY294002 (Figure 3E, n=3, p < 0.05; Figure 3F, n=3, p < 0.05).

Figure 3 Estrogen acutely activates kinase signaling pathways and related downstream pathways. A-D) The p-ERK1/2 and p-Akt proteins were upregulated by 17β-E2 or PPT in MCF-7 cells 15 min or 4h after application, which was blocked by ICI. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 vs 15-min control; #p < 0.05 vs control. E, F) U0126 and LY294002 blocked the upregulation of P2X7R protein induced by 17β-E2 or PPT. G) Estrogen significantly increased expression of phospho-CREB at 15 min, which was blocked by U0126 and LY294002. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 vs control; #p < 0.05 vs 17β-E2 or PPT.

Zhou and his colleagues [33], have reported that the P2X7R gene possesses binding sites for the co transcriptional factor p300. It is well known that CREB can be activated by ERK1/2 or Akt and is associated with p300; therefore, we then further examined the phosphorylation level of CREB (ser133) in MCF-7 cells 15 min after 17β E2 (0.1 μmol/L) application. Western blot analysis demonstrated that in MCF-7 cells estrogen treatment significantly increased expression levels of phospho-CREB at early time points (Figure 3G, n=3, p < 0.05), which were blocked by either U0126 (0.1 μmol/L) or LY294002 (0.1 μmol/L; Figure 3G, n=3, p < 0.05).

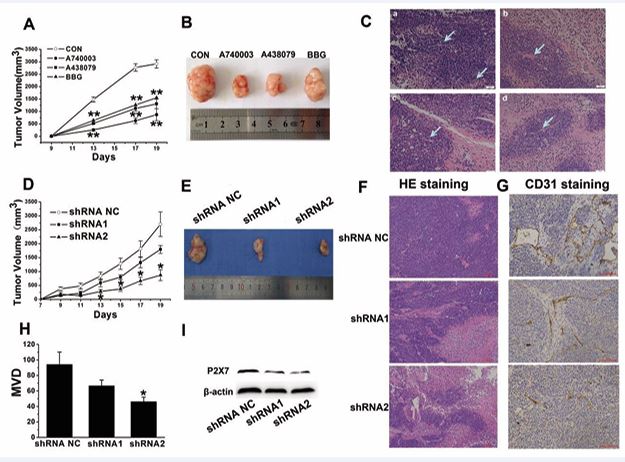

Regression of MCF-7 cells by pharmacological and genetic inactivation of P2X7R in in vivo models.

To investigate whether P2X7R could be a valuable pharmacological target in MCF-7 cells, we studied the effects of P2X7R antagonists on estrogen-related MCF 7 cell growth in vivo. We tested tumors derived from subcutaneous injection of human MCF-7 cells in immune compromised BALB/c mice. A438079 (20 μM), A740003 (10 μM), BBG (1 mg/mL) or placebo (phosphate-buffered saline) was administered intratumorally every 4 days from the appearance of the first tumor mass (day 8 following inoculation) until day 19. Treatment with receptor blockade by both BBG and A438079 caused an almost 50% reduction of the tumor growth rate in live animals (Figure 4A), accompanied by a comparably strong reduction of excised tumor volume (Figure 4B). In addition, A740003 in vivo administration caused a significant reduction (70%) of tumor volume. Histological analysis revealed substantial differences between the groups treated with and without P2X7R antagonists. Tumor cell density was significantly higher in the group after injection of MCF 7 cells compared to animals also treated with P2X7R antagonists. Furthermore, it is well-known that growth of solid tumors depends on adequate vascularization and blood supply. H&E staining in the present study showed a thicker vascular network in the placebo group compared to tumors in animals treated with P2X7R antagonists (Figure 4C).

Figure 4 P2X7R blockade or P2X7R silencing on estrogen-related breast cancer tumor growth. A, D) Tumor growth curves after treatment with the P2X7R antagonists or P2X7R-silenced (P2X7R shRNA) MCF-7 cells. **p < 0.01 vs placebo, *p < 0.05 vs shRNA NC. B, E) Representative tumor masses excised at day 19 post inoculum. C, F) H&E staining of tumors treated with P2X7 antagonists or P2X7R shRNA MCF-7 cells. a: placebo; b: A740003; c: A438079; d: BBG. G, H) CD31 and MVD among P2X7R shRNA MCF-7 cells. *p < 0.05 vs shRNA NC. I) Downregulation of P2X7R in MCF-7 cells infected with shRNA.

To test whether P2X7R expression by the tumor cells might affect tumor growth, we generated stable P2X7R silenced (P2X7R shRNA) MCF-7 cell clones. Characteristics of the P2X7R-silenced MCF-7 cells are shown in Figure 4I. Curves depicting grafted tumor growth and MCF-7 xenografts of the different groups are presented in Figure 4D and E. The tumor volumes in the P2X7R shRNA groups decreased significantly relative to the P2X7R shRNA negative control groups.

To investigate the therapeutic efficacy of P2X7R in the MCF-7 xenograft model, tumor tissue was observed by light microscopy after H&E staining. As shown in Figure 4F, the tumor cells were clustered, large in size, and more densely stained in the P2X7R shRNA negative control group compared with those of the P2X7R shRNA groups. Tumor cell density was significantly higher in the group following injection of MCF-7 cells with the shRNA negative control compared to tumor specimens from the P2X7R shRNA-treated groups.

Tumor angiogenesis is known to depend on the release of angiogenic factors, so we investigated the origin of neoformed vessels by staining with a specific endothelial marker, CD31. After immunostaining with anti-CD31 antibodies, endothelial cells were stained brown to dark brown (Figure 4G). Then we examined the microvessel density by quantifying CD31 expression in solid tumors. We found that the number of endothelial cells or endothelial cell clusters that were stained brown in the P2X7R shRNA groups was significantly reduced compared with those of the shRNA negative control group (Figure 4H).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we found that the P2X7R agonist BzATP could promote proliferation of MCF-7 cells and that the promotion effect of estrogen could be blocked by the P2 receptor antagonist PPADS or the P2X7R-selective antagonist A438079. P2X7R mRNA and protein expression in MCF-7 cells was increased after 17β-E2 treatment, which was blocked by the ER antagonist ICI 182,780, the ERα antagonist MPP, but not by the ERβ antagonist PHTPP. ERα agonist PPT mimicked the effect of estrogen. In addition, ERα siRNA blocked the effect of estrogen on MCF-7 cell proliferation and estrogen modulation of P2X7R protein expression in MCF-7 cells. Estrogen treatment significantly increased the expression level of phospho-CREB within 15 min, which was blocked by U0126 and LY294002. This is the first study to our knowledge to show that estrogen can promote breast cancer cell proliferation by upregulating P2X7R via ERα. Furthermore, administration of three different P2X7 antagonists (A740003, A438079 or BBG) or silencing of P2X7R in MCF-7 cells transplanted into BALB/c mice reduced estrogen-related MCF-7-derived tumor growth and decreased vessel formation.

ATP has been shown to cause a decrease in tumor cell growth, probably via P2X7R [8]. P2X7R is known to induce cytotoxic activity because of its ability to cause opening of non-selective pores in the plasma membrane and activate apoptotic caspases. However, increasing evidence suggests that the P2X7R may also have an apparently paradoxical survival/growth-promoting effect, which seems to vary considerably according to the level of stimulation. Basal ATP release causes tonic stimulation of the P2X7R leading to moderately increased levels of cytoplasmic Ca2+, which plays a central role in cell survival and growth [34]. Moreover, several calcium-related intracellular pathways involved in cell proliferation have been shown to be activated by the P2X7R. These include the JNK/MAPK [35], PI3K/AKT/MYCN [26,36], HIF1α-VEGF [26,36] and NFAT pathways [37,38]. Among these intracellular pathways, the NFAT pathway is well elucidated. NFATc1, a key transcription factor in lymphocyte division and cancer cell growth, exerts a central role in P2X7R-mediated proliferation, as it is strongly upregulated in HEK293 cells expressing different P2X7R isoforms [38]. Interestingly, the P2X7RA and P2X7RB isoforms have differential effects on cell growth. In fact, P2X7RB, which is unable to generate the large conductance pore, confers the highest growth drive [39]. Changes in calcium are unlikely to be solely responsible for the action of P2X7R but may represent a physiological triggering point in diverse upstream and downstream signaling processes that activate different cell functions and responses.

P2X7R has been shown to be overexpressed in breast cancer tissues and is positively associated with ER expression. Down-modulation of P2X7R in MCF-7 breast cancer cells by P2X7R shRNA can reduce cell proliferation, and estrogen effects are consistent with the action of P2X7R in MCF-7 cells [28]. However, data are lacking on possible crosstalk between estrogen and P2X7R in MCF-7 cells. In our study, the E2-induced increase in ERα-positive MCF-7 cell viability could be abolished by P2X receptor antagonist PPADS, indicating an important role of P2X receptors in estrogen stimulation of tumor cell proliferation. Because PPADS is a broad-spectrum inhibitor of P2X receptors, we then used A438079, a selective antagonist of P2X7R. Our results showed that A438079 was effective in blocking the estrogen proliferative effect. However, in the ERα negative MDA-MB-231 cell line, we did not see a similar phenomenon. These findings suggested that P2X7R was involved in the estrogen effect in MCF-7 cells. Furthermore, it is well-known that BzATP can also activate the P2Y11 receptor. We treated the MCF-7 cell line with the P2Y11R antagonist NF 157 and then studied the effect of 17β-E2 on the proliferation of MCF-7 cells. NF 157 failed to inhibit the promotional effect of estrogen, which confirmed activation via P2X7R and indicated that an effect via P2Y11R was unlikely. Our findings thus showed that P2X7R was intimately involved in estrogen-driven proliferation of MCF-7 cells.

In the present study, administration of three different P2X7R antagonists or silencing P2X7R with shRNA in MCF-7 cells injected in nude mice reduced MCF-7 derived tumor growth and decreased vessel formation. It is well-known that growth of solid tumors depends on adequate vascularization and blood supply. Our findings clearly confirmed the possible participation of P2X7R, including its angiogenetic activity, in estrogen-related cancer progression. These results are consistent with the increased neovascularization of P2X7-expressing tumors reported by Adinolfi [15], but are contrary to findings that activation of P2X7 and P2Y11 purinergic receptors inhibits migration of endothelial cells from human breast carcinoma [40]. The underlying mechanism of P2X7R’s role in tumor growth needs further study. It has been widely accepted that breast cancer risk is associated with relatively high concentrations of endogenous estradiol in postmenopausal women [41]. The role of estrogen receptors in mediating the process of proliferation are controversial. ERα appears to promote proliferation while ERβ mainly suppresses the proliferation of tumor cells [5,6]. As such, we hypothesized that ERα may play a role in mediating the promotional effect of estrogen. Our data clearly showed that the ERα antagonist MPP or knockdown of ERα by specific siRNA both significantly reduced estrogen-induced cell proliferation. However, the effect of estrogen could not be blocked by the ERβ antagonist PHTPP or ERβ siRNA. In addition, PPT, a selective ERα agonist, increased proliferation in a dose dependent manner. These results strongly supported the idea that estrogen promotes the proliferation of MCF-7 cells through ERα. We have also discovered that P2X7R may be involved with the estrogen effect on MCF-7 cells. Further research showed that estrogen increased expression of P2X7R at both the mRNA and protein levels in MCF-7 cells. The ER antagonist ICI 182,780 and the ERα antagonist MPP or ERα siRNA blocked the estrogen effect, while the ERβ antagonist PHTPP did not. Similarly, PPT mimicked the effect of estrogen, while DPN had no effect. In the ERα negative breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231, estrogen had no effect on cell growth or the expression of P2X7R at the protein level. Thus, we speculate that estrogen increases the proliferation of breast cancer cells by upregulating the expression of P2X7R via an ERα-related genomic pathway. Estrogen receptors located on the membrane carry out rapid non-genomic actions of estrogen and several studies have shown that acute estrogen treatment can activate a variety of kinase signaling pathways, including MAPK [29,30]. We found that estrogen pretreatment for 15 min and 4 h could activate MAPK/ERK pathways. The use of ICI 182,780 indicated that these effects were mediated directly through ERs. Furthermore, PPT had a similar effect as estrogen, suggesting that ERα was involved. Song [42], has demonstrated that the signaling pathway mediating the rapid action of E2 involved the direct association of ERα with Shc, the phosphorylation of Shc and the formation of Shc-Grb2-Sos complexes, which resulted in MAPK phosphorylation in MCF-7 cells. Furthermore, estrogen, in complex with its receptor, immediately activated c-Src, which could be the initial target of the estradiol-receptor complex in the process leading to activation of the tyrosine phosphorylation/p2lras/MAP-kinase pathway [43].

Similarly, estrogen pre-treatment can activate PI3K/Akt pathways. There is also evidence that estradiol stimulation of MCF-7 cells rapidly triggers association of ERα with Src and p85. The ternary complex probably favors hormone activation of Src- and PI3-kinase dependent pathways, and then activates Akt, which converge on cell cycle progression [44]. Estradiol also activates the PI3-kinase/Akt pathway in endothelial cells [45]. Indeed, in neuroblastoma cells, serum starvation triggers activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway and an induction of P2X7R gene expression takes place, resulting in cell proliferation [46]. In the present study, estrogen and PPT significantly increased ERK1/2 and Akt phosphorylation after 15 min and 4 h, respectively. Pharmacological inhibition of the ERK1/2 pathway by U0126 or the Akt pathway by LY294002 blocked estrogen induced P2X7R expression. Therefore, we suggest that activation of both the ERK pathway and Akt pathway via ERα are a key mechanism for estrogen to induce P2X7R expression and cell proliferation in the MCF-7 cell line.

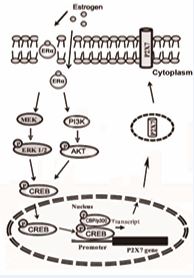

It is well-known that gene expression is regulated by different signaling pathways. MAPK and the PI3K/Akt signal transduction pathway are known to play an important role in driving gene expression in response to a variety of stimuli, including growth factors, proinflammatory cytokines and some stresses. Upon activation, these kinases are phosphorylated and then translocated to nuclei where they induce activation of various transcriptional co activators, including CREB [47,48]. Bioinformatics analysis of the transcription enhancing region of the P2X7R gene revealed that it contained putative binding sites for p300 [32]. The highly conserved co-activators CREB-binding protein (CBP) and its paralog, E1A-binding protein (p300), each have four separate transactivation domains that interact with the transactivation domains of a number of DNA-binding transcriptional activators as well as general transcription factors, thus mediating recruitment of basal transcriptional machinery to the promoter. CBP/p300 contains a catalytic histone acetyltransferase domain that can promote transcription by acetylating histones and integrating signaling from enhancer and promoter regions [49]. It is well-known that phosphorylation of CREB at Ser133 recruits CBP/p300 co-activators to activate transcription [50,51]. Our data clearly showed that estrogen significantly increased the expression levels of phospho-CREB within 15 min and that inhibition of the ERK and Akt pathways reduced CREB. These results suggested that CREB may play an essential role in transmitting ERK1/2 and Akt activation to P2X7R expression. We speculate that exposure of estrogen induces activation of the MEK1/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathway via ERα, which in turn activates CREB, a nuclear co-transcriptional factor. Activated CREB stimulates the phosphorylation of CBP/ p300, and this complex then binds to the P2X7R gene and drives its expression, thereby increasing P2X7R protein levels on the cell surface and subsequently inducing cell proliferation in MCF-7 cells (Figure. 5).

Figure 5 Schematic diagram of estrogen-ERα/ERK or Akt pathway mediated P2X7R expression in MCF-7 cells. Exposure to estrogen induces activation of the MEK1/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways via ERα, which in turn activate CREB, a nuclear co-transcriptional factor. Activated CREB stimulates the phosphorylation of CBP/p300. This complex then binds to the P2X7R gene and drives its expression, thereby increasing P2X7R protein levels on the cell surface and inducing cell proliferation of MCF-7 cells.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this is the first study to our knowledge to show that estrogen promoted breast cancer cell proliferation by upregulating P2X7R via ERα. Estrogen may upregulate P2X7R expression through ERK1/2 or Akt signaling pathways. We preliminarily demonstrated the presence of the estrogen-ERα-ERK1/2 or Akt-pCREB P2X7R signaling pathways in MCF-7 cells. Determining the prognostic significance of the expression of the P2X7R may shed light on this molecular target that may eventually be translated into new clinical therapies for epithelial cancers.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Li-hua Yu and Li-ya Wang performed or participated in all experiments, their analyses and interpretation, and wrote the manuscript. Bei Ma and Ming-juan Xu conceived and designed the study. All authors were involved in the acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are deeply grateful to Dr. Gillian E. Knight (from the Autonomic Neuroscience Centre, University College Medical School, UK) for her kind assistance in English writing. Futhermore, we thank International Science Editing (http://www.internationalscienceediting. com) for editing this manuscript. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31100839) and the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No. 11JC1415300).

REFERENCES

- Veronesi U, Boyle P, Goldhirsch A, Orecchia R, Vialeet G. Breast Cancer. Lancet. 2005; 365: 1727-1741.

- Russo J, Russo IH. The role of estrogen in the initiation of breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006; 102: 89-96.

- Dees C, Askari M, Foster JS, Ahamed S, Wimalasena J. DDT mimicks estradiol stimulation of breast cancer cells to enter the cell cycle. Mol Carcinog. 1997; 18: 107–114.

- Rock CL, Flatt SW, Laughlin GA, Gold EB, Thomson CA, Natarajan L, et al. Reproductive steroid hormones and recurrence-free survival in women with a history of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008; 17: 614–620.

- Lin Z, Reierstad S, Huang CC, Bulun SE. Novel estrogen receptor- alpha binding sites and estradiol target genes identified by chromatin immuno precipitation cloning in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2007; 67: 5017–5024.

- Chan KK, Wei N, Liu SS, Xiao YL, Cheung AN, Ngan HY. Estrogen receptor subtypes in ovarian cancer: a clinical correlation. Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 111: 144-151.

- Burnstock G. Physiology and pathophysiology of purinergic neurotransmission. Physiol Rev. 2007; 87: 659–797.

- Surprenant A, North RA. Signaling at purinergic P2X receptors. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009; 71: 333-359.

- Glaser T, de Oliveira SL, Cheffer A, Beco R, Martins P, Fornazari M, et al. Modulation of mouse embryonic stem cell proliferation and neural differentiation by the P2X7 receptor. PLoS One. 2014; 9: e96281.

- Tsao HK, Chiu PH, Sun SH. PKC-dependent ERK phosphorylation is essential for P2X7 receptor-mediated neuronal differentiation of neural progenitor cells. Cell Death Dis. 2013; 4: e751.

- Rigato C, Swinnen N, Buckinx R, Couillin I, Mangin JM, Rigo JM, et al. Microglia proliferation is controlled by P2X7 receptors in a Pannexin- 1-independent manner during early embryonic spinal cord invasion. J Neurosci. 2012; 32: 11559-11573.

- Agrawal A, Henriksen Z, Syberg S, Petersen S, Aslan D, Solgaard M. P2X7Rs are involved in cell death, growth and cellular signaling in primary human osteoblasts. Bone. 2017; 95: 91-101.

- Yang J, Ma C, Zhang M. High glucose inhibits osteogenic differentiation and proliferation of MC3T3E1 cells by regulating P2X7. Mol Med Rep. 2019; 20: 5084-5090.

- Borges da Silva H, Beura LK, Wang H, Hanse EA, Gore R, Scott MC, et al. The purinergic receptor P2RX7 directs metabolic fitness of long- lived memory CD8(+) T cells. Nature. 2018; 559: 264-268.

- Adinolfi E, Raffaghello L, Giuliani AL, Cavazzini L, Capece M, Chiozzi P, et al. Expression of P2X7 receptor increases in vivo tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2012; 72: 2957-2969.

- Vázquez-Cuevas FG, Martínez-Ramírez AS, Robles-Martínez L, Garay E, García-Carrancá A, Pérez-Montiel D, et al. Paracrine stimulation of P2X7 receptor by ATP activates a proliferative pathway in ovarian carcinoma cells. J Cell Biochem. 2014; 115: 1955-1966.

- Giannuzzo A, Saccomano M, Napp J, Ellegaard M, Alves F, Novak I. Targeting of the P2X7 receptor in pancreatic cancer and stellate cells. Int J Cancer. 2016; 139: 2540-2552.

- Salaro E, Rambaldi A, Falzoni S, Amoroso FS, Franceschini A, Sarti AC, et al. Involvement of the P2X7-NLRP3 axis in leukemic cell proliferation and death. Sci Rep. 2016; 6: 26280.

- Ji Z, Xie Y, Guan Y, Zhang Y, Cho KS, Ji M. Involvement of P2X7 Receptor

in Proliferation and Migration of Human Glioma Cells. BioMed Res Int. 2018; 2018: 8591397.

- Jelassi B, Chantôme A, Alcaraz-Pérez F, Baroja-Mazo A, Cayuela ML, Pelegrin P, et al. P2X(7) receptor activation enhances SK3 channels- and cystein cathepsin-dependent cancer cells invasiveness. Oncogene. 2011; 30: 2108-2122.

- Jelassi B, Anchelin M, Chamouton J, Cayuela ML, Clarysse L, Li J, et al. Anthraquinone emodin inhibits human cancer cell invasiveness by antagonizing P2X7 receptors. Carcinogenesis. 2013; 34: 1487-1496.

- Qiu Y, Li WH, Zhang HQ, Liu Y, Tian XX, Fang WG. P2X7 mediates ATP-driven invasiveness in prostate cancer cells. PLoS One. 2014; 9: e114371.

- Adinolfi E, Capece M, Franceschini A, Falzoni S, Giuliani AL, Rotondo A, et al. Accelerated tumor progression in mice lacking the ATP receptor P2X7. Cancer Res. 2015; 75: 635-644.

- Amoroso F, Salaro E, Falzoni S, Chiozzi P, Giuliani AL, Cavallesco G. P2X7 targeting inhibits growth of human mesothelioma. Oncotarget. 2016; 7: 49664-49676.

- Kan LK, Seneviratne S, Drummond K, Williams D, O’Brien T, Monif M. P2X7 receptor antagonism inhibits tumour growth in human high- grade glomas. Purinergic Signalling. 2020; 16: 327-336;

- Zhang Y, Cheng H, Li W, Wu H, Yang Y. Highly-expressed P2X7 receptor promotes growth and metastasis of human HOS/MNNG osteosarcoma cells via PI3K/Akt/GSK3beta/beta-catenin and mTOR/ HIF1alpha/VEGF signaling. Int J Cancer. 2019; 145: 1068-1082.

- De Marchi E, Orioli E, Pegoraro A, Sangaletti S, Portararo P, Curti A, et al. The P2X7 receptor modulates immune cells infiltration, ectonucleotidases expression and extracellular ATP levels in the tumor microenvironment. Oncogene. 2019; 38: 3636-3650.

- Tan C, Han LI, Zou L, Luo C, Liu A, Sheng X, et al. Expression of P2X7R in breast cancer tissue and the induction of apoptosis by the gene- specific shRNA in MCF-7 cells. Exp Ther Med. 2015; 10: 1472-1478.

- Li HJ, Wang LY, Qu HN, Yu LH, Burnstock G, Ni X, et al. P2Y2 receptor- mediated modulation of estrogen-induced proliferation of breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011; 338: 28-37.

- Jover-Mengual T, Zukin RS, Etgen AM. MAPK signaling is critical to estradiol protection of CA1 neurons in global ischemia. Endocrinology. 2007; 148: 1131-1143.

- Zhao L, Brinton RD. Estrogen receptor alpha and beta differentially regulate intracellular Ca(2+) dynamics leading to ERK phosphorylation and estrogen neuroprotection in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2007; 1172: 48-59.

- Cimarosti H, Zamin LL, Frozza R, Nassif M, Horn AP, Tavares A, et al. Estradiol protects against oxygen and glucose deprivation in rat hippocampal organotypic cultures and activates Akt and inactivates GSK-3beta. Neurochem Res. 2005; 30: 191-199.

- Zhou L, Luo L, Qi X, Li X, Gorodeski GI. Regulation of P2X(7) gene transcription. Purinergic Signal. 2009; 5: 409-426.

- Di Virgilio F, Ferrari D, Adinolfi E. P2X(7): a growth-promoting receptor-implications for cancer. Purinergic Signal. 2009; 5: 251-256.

- Choi JH, Ji YG, Ko JJ, Cho HJ, Lee DH. Activating P2X7 Receptors Increases Proliferation of Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells via ERK1/2 and JNK. Pancreas. 2018; 47: 643-651.

- Amoroso F, Capece M, Rotondo A, Cangelosi D, Ferracin M, Franceschini A, et al. The P2X7 receptor is a key modulator of the PI3K/GSK3β/VEGF signaling network: evidence in experimental neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 2015; 34: 5240-5251.

- Adinolfi E, Callegari MG, Cirillo M, Pinton P, Giorgi C, Cavagna D, et al. Expression of the P2X7 receptor increases the Ca2+ content of the endoplasmic reticulum, activates NFATc1, and protects from apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2009; 284: 10120-10128.

- Adinolfi E, Cirillo M, Woltersdorf R, Falzoni S, Chiozzi P, Pellegatti P, et al. Trophic activity of a naturally occurring truncated isoform of the P2X7 receptor. FASEB J. 2010; 24: 3393-3404.

- Giuliani AL, Colognesi D, Ricco T, Roncato C, Capece M, Amoroso F, et al. Trophic activity of human P2X7 receptor isoforms A and B in osteosarcoma. PLoS One. 2014; 9: e107224.

- Avanzato D, Genova T, Fiorio Pla A, Bernardini M, Bianco S, Bussolati B, et al. Activation of P2X7 and P2Y11 purinergic receptors inhibits migration and normalizes tumor-derived endothelial cells via cAMP signaling. Sci Rep. 2016; 6: 32602.

- Folkerd EJ, Martin LA, Kendall A, Dowsett M. The relationship between factors affecting endogenous oestradiol levels in postmenopausal women and breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006; 102: 250-255.

- Song RX, McPherson RA, Adam L, Bao Y, Shupnik M, Kumar R, et al. Linkage of rapid estrogen action to MAPK activation by ERalpha-Shc association and Shc pathway activation. Mol Endocrinol. 2002; 16: 116-127.

- Migliaccio A, Di Domenico M, Castoria G, de Falco A, Bontempo P, Nola E, et al. Tyrosine kinase/p21ras/MAP-kinase pathway activation by estradiol-receptor complex in MCF-7 cells. EMBO J. 1996; 15: 1292- 300.

- Castoria G, Migliaccio A, Bilancio A, Di Domenico M, de Falco A, Lombardi M, et al. PI3-kinase in concert with Src promotes the S-phase entry of oestradiol-stimulated MCF-7 cells. EMBO J. 2001; 20: 6050-6059.

- Simoncini T, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Brazil DP, Ley K, Chin WW, Liao JK. Interaction of oestrogen receptor with the regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase. Nature. 2000; 407: 538-541.

- Gómez-Villafuertes R, García-Huerta P, Díaz-Hernández JI, Miras- Portugal MT. PI3K/Akt signaling pathway triggers P2X7 receptor expression as a pro-survival factor of neuroblastoma cells under limiting growth conditions. Sci Rep. 2015; 5: 18417.

- Davis S, Vanhoutte P, Pages C, Caboche J, Laroche S. The MAPK/ERK cascade targets both Elk-1 and cAMP response element-binding protein to control long-term potentiation-dependent gene expression in the dentate gyrus in vivo. J Neurosci. 2000; 20: 4563-4572.

- Brami-Cherrier K, Valjent E, Garcia M, Pagès C, Hipskind RA, CabocheJ. Dopamine induces a PI3-kinase-independent activation of Akt in striatal neurons: a new route to cAMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2002; 22: 8911-8921.

- Li M, Luo J, Brooks CL, Gu W. Acetylation of p53 inhibits its ubiquitination by Mdm2. J Biol Chem. 2002; 277: 50607-50611.

- Chrivia JC, Kwok RP, Lamb N, Hagiwara M, Montminy MR, Goodman RH. Phosphorylated CREB binds specifically to the nuclear protein CBP. Nature. 1993; 365: 855-859.

- Parker D, Ferreri K, Nakajima T, LaMorte VJ, Evans R, Koerber SC, et al. Phosphorylation of CREB at Ser-133 induces complex formation with CREB-binding protein via a dire References

- Veronesi U, Boyle P, Goldhirsch A, Orecchia R, Vialeet G. Breast Cancer. Lancet. 2005; 365: 1727-1741.

- Russo J, Russo IH. The role of estrogen in the initiation of breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006; 102: 89-96.

- Dees C, Askari M, Foster JS, Ahamed S, Wimalasena J. DDT mimicks

estradiol stimulation of breast cancer cells to enter the cell cycle. Mol Carcinog. 1997; 18: 107–114.

- Rock CL, Flatt SW, Laughlin GA, Gold EB, Thomson CA, Natarajan L, et al. Reproductive steroid hormones and recurrence-free survival in women with a history of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008; 17: 614–620.

- Lin Z, Reierstad S, Huang CC, Bulun SE. Novel estrogen receptor- alpha binding sites and estradiol target genes identified by chromatin immuno precipitation cloning in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2007; 67: 5017–5024.

- Chan KK, Wei N, Liu SS, Xiao YL, Cheung AN, Ngan HY. Estrogen receptor subtypes in ovarian cancer: a clinical correlation. Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 111: 144-151.

- Burnstock G. Physiology and pathophysiology of purinergic neurotransmission. Physiol Rev. 2007; 87: 659–797.

- Surprenant A, North RA. Signaling at purinergic P2X receptors. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009; 71: 333-359.

- Glaser T, de Oliveira SL, Cheffer A, Beco R, Martins P, Fornazari M, et al. Modulation of mouse embryonic stem cell proliferation and neural differentiation by the P2X7 receptor. PLoS One. 2014; 9: e96281.

- Tsao HK, Chiu PH, Sun SH. PKC-dependent ERK phosphorylation is essential for P2X7 receptor-mediated neuronal differentiation of neural progenitor cells. Cell Death Dis. 2013; 4: e751.

- Rigato C, Swinnen N, Buckinx R, Couillin I, Mangin JM, Rigo JM, et al. Microglia proliferation is controlled by P2X7 receptors in a Pannexin- 1-independent manner during early embryonic spinal cord invasion. J Neurosci. 2012; 32: 11559-11573.

- Agrawal A, Henriksen Z, Syberg S, Petersen S, Aslan D, Solgaard M. P2X7Rs are involved in cell death, growth and cellular signaling in primary human osteoblasts. Bone. 2017; 95: 91-101.

- Yang J, Ma C, Zhang M. High glucose inhibits osteogenic differentiation and proliferation of MC3T3E1 cells by regulating P2X7. Mol Med Rep. 2019; 20: 5084-5090.

- Borges da Silva H, Beura LK, Wang H, Hanse EA, Gore R, Scott MC, et al. The purinergic receptor P2RX7 directs metabolic fitness of long- lived memory CD8(+) T cells. Nature. 2018; 559: 264-268.

- Adinolfi E, Raffaghello L, Giuliani AL, Cavazzini L, Capece M, Chiozzi P, et al. Expression of P2X7 receptor increases in vivo tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2012; 72: 2957-2969.

- Vázquez-Cuevas FG, Martínez-Ramírez AS, Robles-Martínez L, Garay E, García-Carrancá A, Pérez-Montiel D, et al. Paracrine stimulation of P2X7 receptor by ATP activates a proliferative pathway in ovarian carcinoma cells. J Cell Biochem. 2014; 115: 1955-1966.

- Giannuzzo A, Saccomano M, Napp J, Ellegaard M, Alves F, Novak I. Targeting of the P2X7 receptor in pancreatic cancer and stellate cells. Int J Cancer. 2016; 139: 2540-2552.

- Salaro E, Rambaldi A, Falzoni S, Amoroso FS, Franceschini A, Sarti AC, et al. Involvement of the P2X7-NLRP3 axis in leukemic cell proliferation and death. Sci Rep. 2016; 6: 26280.

- Ji Z, Xie Y, Guan Y, Zhang Y, Cho KS, Ji M. Involvement of P2X7 Receptor in Proliferation and Migration of Human Glioma Cells. BioMed Res Int. 2018; 2018: 8591397.

- Jelassi B, Chantôme A, Alcaraz-Pérez F, Baroja-Mazo A, Cayuela ML, Pelegrin P, et al. P2X(7) receptor activation enhances SK3 channels- and cystein cathepsin-dependent cancer cells invasiveness. Oncogene. 2011; 30: 2108-2122.

- Jelassi B, Anchelin M, Chamouton J, Cayuela ML, Clarysse L, Li J, et

al. Anthraquinone emodin inhibits human cancer cell invasiveness by antagonizing P2X7 receptors. Carcinogenesis. 2013; 34: 1487-1496.

- Qiu Y, Li WH, Zhang HQ, Liu Y, Tian XX, Fang WG. P2X7 mediates ATP-driven invasiveness in prostate cancer cells. PLoS One. 2014; 9: e114371.

- Adinolfi E, Capece M, Franceschini A, Falzoni S, Giuliani AL, Rotondo A, et al. Accelerated tumor progression in mice lacking the ATP receptor P2X7. Cancer Res. 2015; 75: 635-644.

- Amoroso F, Salaro E, Falzoni S, Chiozzi P, Giuliani AL, Cavallesco G. P2X7 targeting inhibits growth of human mesothelioma. Oncotarget. 2016; 7: 49664-49676.

- Kan LK, Seneviratne S, Drummond K, Williams D, O’Brien T, Monif M. P2X7 receptor antagonism inhibits tumour growth in human high- grade glomas. Purinergic Signalling. 2020; 16: 327-336;

- Zhang Y, Cheng H, Li W, Wu H, Yang Y. Highly-expressed P2X7 receptor promotes growth and metastasis of human HOS/MNNG osteosarcoma cells via PI3K/Akt/GSK3beta/beta-catenin and mTOR/ HIF1alpha/VEGF signaling. Int J Cancer. 2019; 145: 1068-1082.

- De Marchi E, Orioli E, Pegoraro A, Sangaletti S, Portararo P, Curti A, et al. The P2X7 receptor modulates immune cells infiltration, ectonucleotidases expression and extracellular ATP levels in the tumor microenvironment. Oncogene. 2019; 38: 3636-3650.

- Tan C, Han LI, Zou L, Luo C, Liu A, Sheng X, et al. Expression of P2X7R in breast cancer tissue and the induction of apoptosis by the gene- specific shRNA in MCF-7 cells. Exp Ther Med. 2015; 10: 1472-1478.

- Li HJ, Wang LY, Qu HN, Yu LH, Burnstock G, Ni X, et al. P2Y2 receptor- mediated modulation of estrogen-induced proliferation of breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011; 338: 28-37.

- Jover-Mengual T, Zukin RS, Etgen AM. MAPK signaling is critical to estradiol protection of CA1 neurons in global ischemia. Endocrinology. 2007; 148: 1131-1143.

- Zhao L, Brinton RD. Estrogen receptor alpha and beta differentially regulate intracellular Ca(2+) dynamics leading to ERK phosphorylation and estrogen neuroprotection in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2007; 1172: 48-59.

- Cimarosti H, Zamin LL, Frozza R, Nassif M, Horn AP, Tavares A, et al. Estradiol protects against oxygen and glucose deprivation in rat hippocampal organotypic cultures and activates Akt and inactivates GSK-3beta. Neurochem Res. 2005; 30: 191-199.

- Zhou L, Luo L, Qi X, Li X, Gorodeski GI. Regulation of P2X(7) gene transcription. Purinergic Signal. 2009; 5: 409-426.

- Di Virgilio F, Ferrari D, Adinolfi E. P2X(7): a growth-promoting receptor-implications for cancer. Purinergic Signal. 2009; 5: 251-256.

- Choi JH, Ji YG, Ko JJ, Cho HJ, Lee DH. Activating P2X7 Receptors Increases Proliferation of Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells via ERK1/2 and JNK. Pancreas. 2018; 47: 643-651.

- Amoroso F, Capece M, Rotondo A, Cangelosi D, Ferracin M, Franceschini A, et al. The P2X7 receptor is a key modulator of the PI3K/GSK3β/VEGF signaling network: evidence in experimental neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 2015; 34: 5240-5251.

- Adinolfi E, Callegari MG, Cirillo M, Pinton P, Giorgi C, Cavagna D, et al. Expression of the P2X7 receptor increases the Ca2+ content of the endoplasmic reticulum, activates NFATc1, and protects from apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2009; 284: 10120-10128.

- Adinolfi E, Cirillo M, Woltersdorf R, Falzoni S, Chiozzi P, Pellegatti P, et al. Trophic activity of a naturally occurring truncated isoform of the P2X7 receptor. FASEB J. 2010; 24: 3393-3404.

- Giuliani AL, Colognesi D, Ricco T, Roncato C, Capece M, Amoroso F, et al. Trophic activity of human P2X7 receptor isoforms A and B in osteosarcoma. PLoS One. 2014; 9: e107224.

- Avanzato D, Genova T, Fiorio Pla A, Bernardini M, Bianco S, Bussolati B, et al. Activation of P2X7 and P2Y11 purinergic receptors inhibits migration and normalizes tumor-derived endothelial cells via cAMP signaling. Sci Rep. 2016; 6: 32602.

- Folkerd EJ, Martin LA, Kendall A, Dowsett M. The relationship between factors affecting endogenous oestradiol levels in postmenopausal women and breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006; 102: 250-255.

- Song RX, McPherson RA, Adam L, Bao Y, Shupnik M, Kumar R, et al. Linkage of rapid estrogen action to MAPK activation by ERalpha-Shc association and Shc pathway activation. Mol Endocrinol. 2002; 16: 116-127.

- Migliaccio A, Di Domenico M, Castoria G, de Falco A, Bontempo P, Nola E, et al. Tyrosine kinase/p21ras/MAP-kinase pathway activation by estradiol-receptor complex in MCF-7 cells. EMBO J. 1996; 15: 1292- 300.

- Castoria G, Migliaccio A, Bilancio A, Di Domenico M, de Falco A, Lombardi M, et al. PI3-kinase in concert with Src promotes the S-phase entry of oestradiol-stimulated MCF-7 cells. EMBO J. 2001; 20: 6050-6059.

- Simoncini T, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Brazil DP, Ley K, Chin WW, LiaoJK. Interaction of oestrogen receptor with the regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase. Nature. 2000; 407: 538-541.

- Gómez-Villafuertes R, García-Huerta P, Díaz-Hernández JI, Miras- Portugal MT. PI3K/Akt signaling pathway triggers P2X7 receptor expression as a pro-survival factor of neuroblastoma cells under limiting growth conditions. Sci Rep. 2015; 5: 18417.

- Davis S, Vanhoutte P, Pages C, Caboche J, Laroche S. The MAPK/ERK cascade targets both Elk-1 and cAMP response element-binding protein to control long-term potentiation-dependent gene expression in the dentate gyrus in vivo. J Neurosci. 2000; 20: 4563-4572.

- Brami-Cherrier K, Valjent E, Garcia M, Pagès C, Hipskind RA, CabocheJ. Dopamine induces a PI3-kinase-independent activation of Akt in striatal neurons: a new route to cAMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2002; 22: 8911-8921.

- Li M, Luo J, Brooks CL, Gu W. Acetylation of p53 inhibits its ubiquitination by Mdm2. J Biol Chem. 2002; 277: 50607-50611.

- Chrivia JC, Kwok RP, Lamb N, Hagiwara M, Montminy MR, Goodman RH. Phosphorylated CREB binds specifically to the nuclear protein CBP. Nature. 1993; 365: 855-859.

- Parker D, Ferreri K, Nakajima T, LaMorte VJ, Evans R, Koerber SC, et al. Phosphorylation of CREB at Ser-133 induces complex formation with CREB-binding protein via a direct mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 1996; 16: 694-703.

- ct mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 1996; 16: 694-703.