Sailing Without a Map: A Review of the Quality of Acute Kidney Injury Care

- 1. Hull University Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, United Kingdom

- 2. Hull York Medical School, United Kingdom

Abstract

Introduction: This study evaluates the quality acute kidney injury (AKI) care in two tertiary care hospitals of an NHS Trust.

Methods: Adult patients meeting the clinical and biochemical criteria for AKI diagnosis were eligible for inclusion. Renal ward or intensive care admissions, patients with end-stage kidney disease or receiving palliative care were excluded. Patients were selected from a database of all reported cases of AKI that occurred during May 2023. Two investigators independently reviewed case notes and collected data using a proforma based on a national audit tool. Outcomes were reported as proportions and compared between AKI stages.

Results: Data points were extracted from 28 (AKI 1), 27 (AKI 2) and 29 (AKI 3) patients. On recognition of AKI, acid-base balance was performed in 14%, 44% and 66%. Urinalysis was performed in 11%, 15% and 14%. Renal Ultrasound was performed in 15%, 11% and 31%. Sepsis screening was donein 25%, 33% and 66%. Fluid balance was monitored in 36%, 37% and 55%. Management involved volume replacement in 61%, 74% and 86%. Diureticswere administered in 15%, 11% and 14%. Diuretics were withheld in 14%, 15% and 18%. Medications review was performed in 21%, 37% and 72%.Catheterisation was done in 29%, 37% and 72%. A nephrology referral was made in 7%, 45% and 18%.

Discussion: Compliance with national guidance for the investigation and management of AKI is suboptimal. We identify a need to improve clinician education in its management principles alongside the indications for specialist input.

Keywords

• Acute Kidney Injury

• Patient Outcomes

• Quality Improvement

Citation

Clarkson M, Stokes S, Spencer S, Desborough R (2025) Sailing Without a Map: A Review of the Quality of Acute Kidney Injury Care. J Clin Nephrol Res 12(1): 1126.

INTRODUCTION

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a rapid decline in renal function, characterised by a rise in serum creatinine, a reduction in urine output, or both. AKI typically develops over hours to days and can arise from a variety of causes, including kidney hypoperfusion, intrinsic kidney disease, nephrotoxic exposure, or urinary outflow obstruction [1]. AKI is frequently detected in patients presenting acutely to hospital (community-acquired), but can also develop during hospital admissions, or following discharge (hospital-acquired). The reported incidence of AKI varies widely in the literature. A study of admissions to acute medical units (AMUs) at two UK district general hospitals reported an overall AKI incidence of 6.4%, with 4.3% attributed to community-acquired AKI and 2.1% to hospital-acquired AKI [2]. Similarly, a multicentre prospective observational study across 10 AMUs in England and Scotland found AKI in 17.7% of patients on admission, with an additional 3.5% developing AKI within 72 hours of admission [3]. AKI places a significant burden on patients, with a median hospital stay of 7 days for community-acquired AKI and 15 days for hospital-acquired AKI, alongside mortality rates of 22% and 43%, respectively [4]. Left untreated, AKI can result in complications such as uraemia, acidosis, hyperkalaemia and death, making early recognition and management critical [5]. AKI increases the long-term risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) as well as progression to end stage kidney disease (ESKD) in those with established CKD [6]. AKI is prevalent in about 50% of critically unwell patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Survivors of critical illness with stage 2 or 3 AKI suffer worse quality of life, physical deconditioning and reduced return to work and driving rates than those with stage 1 or no AKI at 3-months post-ICU discharge [7]. The economic burden of AKI is significant with an estimated annual cost of £1.02 billion on AKI-related inpatient care in England, driven by associated prolonged hospital stays, intensive care admissions and hospital readmission, as well as the increased risk of long-term health problems [8,9] In 2009, the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD) demonstrated nationwide deficiencies in AKI care, revealing that only 50% of cases were managed to an acceptable standard. Delays in recognising post-admission AKI were identified in 43% of cases, underscoring the need for improved systems for detection and management. Recommendations included routine AKI risk assessments for emergency admissions, better management of acutely unwell patients with AKI and eliminating preventable AKIs [5]. To address these challenges, NHS England introduced a national AKI detection algorithm in 2014 integrating it into Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS), to generate electronic alerts (e-alerts) when serum creatinine levels reach the diagnostic threshold for AKI [10]. At Hull University Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust (HUTH) the implementation of e-alerts improved AKI recognition from 15% in 2013 to 43% in 2018, along with better assessment practices such as reviewing biochemistry, acid-base parameters, fluid balance and consideration of sepsis. However, there was little demonstrable improvement in the management of established AKI, such as correcting hypovolaemia, investigating obstruction, or initiating renal referrals [11].

Prior to 2023, HUTH Blood Sciences communicated AKI e-alerts on all Primary Care requests, via telephone. This was in addition to the release of e-alerts. From March 2023 onwards, the phoning of e-alerts was extended to all patients irrespective of location. This audit evaluates the approaches to AKI recognition and the quality of care across AKI stages amongst hospitalised inpatients, completing a 10-year review of AKI care at HUTH.

METHODS

Setting and approval

This study was completed at a large tertiary NHS teaching hospital Trust. Local Audit approval was granted to undertake this study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Adult patients who met the clinical and biochemical criteria for AKI diagnosis, either on admission or during inpatient stay, were eligible for inclusion in this study. Amongst patients with multiple episodes of AKI, only the first episode was analysed. Criteria for exclusion included patients admitted to either the renal ward or ICU, patients with known ESKD and those receiving palliative care at the time of diagnosis of AKI.

Data Collection

Patients were selected from a database of all reported cases of AKI that occurred within the Trust over a two month period from 1st May 2023 to 30th June 2023. A data collection proforma based on the NCEPOD audit tool was used [9], to obtain data pertinent to the assessment and management of patients with AKI. Episodes of AKI were classified as either community-acquired if they occurred within 48 hours of hospital admission, or hospital-acquired if onset of AKI was after this. Two study investigators independently reviewed patient case notes and collected data using the proforma. Any uncertainties were discussed between investigators and with a third investigator to maintain consistency and quality assurance.

Data Analysis

Patient characteristics and outcomes were compared between AKI stages (Table 1).

Table 1: Summary of patient characteristics. * Kruskal-Wallis Test, ** Fisher’s Exact Test, *** Chi-square Test.

|

|

AKI 1 |

AKI 2 |

AKI 3 |

P-value |

|

|

Number, n (%) |

28 (33%) |

27 (32%) |

29 (35%) |

|

|

|

Age, median (IQR) |

73 (60-80) |

76 (62-90) |

69 (54-84) |

0.0565* |

|

|

Female, n (%) |

8 (28%) |

20 (74%) |

17 (59%) |

0.8025** |

|

|

AKI type, n (%) |

Hospital-acquired |

10 (36%) |

9 (33%) |

7 (24%) |

0.632** |

|

Community-acquired |

18 (64%) |

18 (67%) |

22 (76%) |

0.632* |

|

|

Grade of first reviewing doctor, n (%) |

Consultant |

6 (21%) |

0 (0%) |

8 (28%) |

0.0001** |

|

Registrar |

1 (4%) |

3 (11%) |

7 (24%) |

0.0001** |

|

|

Core Trainee |

5 (18%) |

5 (19%) |

3 (10%) |

0.0001** |

|

|

Foundation |

1 (4%) |

0 (0%) |

4 (14%) |

0.0001** |

|

|

Other |

4 (14%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0.0001** |

|

|

Undocumented |

11 (39%) |

19 (70%) |

7 (24%) |

0.0001** |

|

|

1-Month Mortality, n (%) |

5 (18%) |

4 (15%) |

8 (30%) |

0.495*** |

|

|

6-month mortality, n (%) |

11 (38%) |

13 (48%) |

10 (34%) |

0.595 *** |

|

Characteristics are reported as proportions or medians with interquartile ranges. Baseline categorical data were analysed using Fisher’s Exact Test for ‘gender’ and ‘grade of first reviewing doctor’, and the Chi-Square Test for ‘1- and 6-month mortality’. Patient age, as a continuous variable, was compared using the Kruskal-Wallis Test.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics and Characteristics

90 patient case notes were reviewed, comprising an equal number of cases for each stage of acute kidney injury (AKI 1, 2, and 3; n = 30 per group). Data points were extracted from 84 patients; six cases were excluded due to insufficient documentation relating to the relevant hospital admission. Across all AKI stages, median age and weight were broadly similar, with no significant association between the median age and AKI stage (p = 0.0565). A higher proportion of patients were female, however there was no significant association between gender distribution and AKI stage (p = 0.8025) (Table 1).

For AKI 1, 64% were community-acquired (n = 18) and 36% hospital-acquired (n = 10). For AKI 2, 67% were community-acquired (n = 18) and 33% hospital-acquired (n = 9). In AKI 3, 76% were community-acquired (n = 22) and 24% hospital-acquired (n = 7). The proportion of community-acquired versus hospital-acquired AKI did not differ significantly across AKI stages (p = 0.632) (Table 1).The grade of the first reviewing clinician was reported in 61%, 30% and 76% of patients with AKIs 1, 2 and 3 respectively. The grade of the reviewing clinician was undocumented in 39%, 70% and 24% of cases respectively. For AKI 1, the grade of the first reviewing clinician was most often documented by a consultant (21%), followed by: core trainee (18%), other (14%), foundation trainee (4%) or registrar (4%). For AKI 2, this was documented by a core trainee (19%) or registrar (11%). For AKI 3, documented review was by a consultant (28%), registrar (24%), foundation trainee (14%) or core trainee (10%). Differences in the grade of the first reviewing clinician were significant across AKI stages (p = 0.001) (Table 1).Short- and longer-term mortality differed by AKI stage. One-month mortality was 18% for AKI 1 and 30% for AKI 3. At six months, mortality increased to 38% for AKI 1 and 34% for AKI 3. Patients with AKI 2 had the highest six-month mortality rate, at 48%. However, differences in the 1-month and 6-month mortality rates did not differ significantly across AKI stages (p = 0.495, p = 0.595) (Table 1).

Risk Assessment

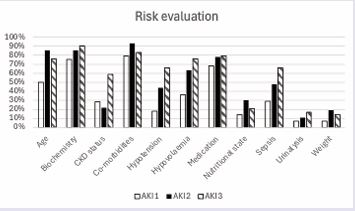

Tasks and information gathered to assess AKI risk during the first inpatient medical review were explored (Table 2) (Figure 1).

Table 2: Summary of raw data on the compliance with clinical tasks across AKI stages.

|

|

AKI 1 |

AKI 2 |

AKI 3 |

All |

|

Risk evaluation, n (%) |

|

|||

|

Age |

14 (50%) |

23 (85.2%) |

1 |

59 (70.2%) |

|

Biochemistry |

21 (75%) |

23 (85.2%) |

26 (89.7%) |

70 (83.3%) |

|

CKD status |

8 (28.6%) |

6 (22.2%) |

17 (58.6%) |

31 (36.9%) |

|

Co-morbidities |

22 (78.6%) |

25 (92.6%) |

24 (82.8%) |

71 (84.5%) |

|

Hypotension |

5 (17.9%) |

12 (44.4%) |

19 (65.5%) |

36 (42.9%) |

|

Hypovolaemia |

10 (35.7%) |

17 (63.0%) |

22 (75.9%) |

49 (58.3%) |

|

Medication |

19 (67.9%) |

21 (78%) |

23 (79%) |

63 (84%) |

|

Nutritional status |

4 (14.29%) |

8 (29.6%) |

6 (20.7%) |

18 (21.4%) |

|

Sepsis |

8 (28.57%) |

13 (48.1%) |

19 (65.5%) |

40 (47.6%) |

|

Urinalysis |

2 (7.1%) |

3 (11.1%) |

5 (17.2%) |

10 (11.9%) |

|

Weight |

2 (7.1%) |

5 (18.5%) |

4 (13.8%) |

11 (13.1%) |

|

Diagnostic interventions, n (%) |

|

|||

|

Acid base balance |

4 (14.3%) |

12 (44.4%) |

19 (65.5%) |

35 (41.7%) |

|

Biochemistry |

21 (75%) |

19 (70.4%) |

20 (69.0%) |

60 (71.4%) |

|

CT renal tract |

1 (3.6%) |

1 (3.7%) |

7 (24.1%) |

9 (10.7%) |

|

Documentation of AKI diagnosis |

21 (75%) |

25 (92.6%) |

27 (93.1%) |

73 (86.9%) |

|

Early warning score |

20 (71.4%) |

18 (66.7%) |

22 (75.9%) |

60 (71.4%) |

|

Fluid balance |

10 (35.7%) |

10 (37.0%) |

16 (55.2%) |

36 (42.9%) |

|

Immunology |

1 (3.6%) |

1 (3.7%) |

1 (3.4%) |

3 (3.6%) |

|

MRI |

0 |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

Renal biopsy |

1 (3.6%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (6.9%) |

3 (3.6%) |

|

Sepsis recognition |

7 (25%) |

9 (33.3%) |

19 (65.5%) |

35 (41.7%) |

|

Urinalysis |

3 (10.7%) |

4 (14.8%) |

4 (13.8%) |

11 (13.1%) |

|

USS renal |

4 (14.5%) |

3 (11.1%) |

9 (31.0%) |

16 (19.0%) |

|

Management of AKI, n (%) |

|

|||

|

Adequate monitoring of BCP |

22 (78.6%) |

19 (70.4%) |

26 (89.7%) |

67 (79.8%) |

|

Administration of diuretics |

4 (14.9%) |

3 (11.1%) |

4 (13.8%) |

11 (13.1%) |

|

Antibiotics |

10 (35.7%) |

16 (59.3%) |

17 (58.6%) |

43 (51.2%) |

|

Catheter |

8 (28.6%) |

10 (37.0%) |

21 (72.4%) |

39 (46.4%) |

|

Cessation of diuretics |

4 (14.29%) |

4 (14.8%) |

7 (24.1%) |

15 (17.9%) |

|

Correction of hypovolaemia |

17 (60.7%) |

20 (74.1%) |

25 (86.2%) |

62 (73.8%) |

|

Daily weight chart |

1 (3.6%) |

3 (11.1%) |

3 (10.3%) |

7 (8.3%) |

|

Fluid balance chart |

9 (32.14%) |

15 (55.6%) |

16 (55.2%) |

40 (47.6%) |

|

Interventional radiology |

1 (3.6%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (3.4%) |

2 (2.4%) |

|

Medication review |

6 (21.4%) |

10 (37.0%) |

21 (72.4%) |

37 (44.0%) |

|

Renal dosing of medications |

2 (7.1%) |

4 (14.8%) |

18 (62.1%) |

24 (28.6%) |

|

Surgery |

1 (3.6%) |

2 (7.4%) |

2 (6.9%) |

5 (6.0%) |

|

Nephrology referral, n (%) |

|

|||

|

Yes |

0 |

2 (7.4%) |

13 (44.8%) |

15 (17.9%) |

|

Seen by renal physician |

0 |

2 (7.4%) |

8 (27.6%) |

10 (11.9%) |

|

Advice given |

0 |

1 (3.7%) |

10 (34.5%) |

11 (13.1%) |

|

Patient accepted |

0 |

1 (3.7%) |

3 (10.3%) |

4 (4.8%) |

Figure 1 Documented evidence of risk assessment during the first medical review for patients across AKI stages.

Urinalysis was performed in 7%, 11% and 17% of patients with AKI stages 1, 2 and 3 respectively. The patient’s biochemistry results were documented in 75%, 85% and 90% of cases respectively. Acknowledgement of the patient’s regular medications was documented in 68%, 78% and 79% of cases. CKD status was acknowledged and documented in 29%, 22% and 59% of cases respectively.Hypotension was present during the first medical review in 18%, 44% and 66% of cases respectively across AKI stages. Hypovolaemia was acknowledged amongst 36%, 63% and 76% of cases.

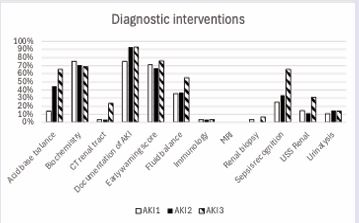

Diagnostic Investigations

AKI recognition was documented in the case notes in 87% of cases. This was done for 75%, 93% and 93% of cases amongst AKI stages 1, 2 and 3 respectively. Upon recognition of AKI, fluid balance monitoring was performed in 36% (AKI 1), 37% (AKI 2) and 55% (AKI 3) of cases. Urinalysis was ascertained in 11% (AKI 1), 15% (AKI 2) and 14% (AKI 3) of patients. Evidence of sepsis screening occurred in 25% (AKI 1), 33% (AKI 2) and 66% (AKI 3). Urinary tract ultrasound was carried out in 15% (AKI 1), 11% (AKI 2) and 31% (AKI 3). Acid base balance through venous or arterial blood sampling was available in 14% (AKI 1), 44% (AKI 2) and 66% (AKI 3) of cases.Regular monitoring of biochemistry was evident amongst 75% (AKI 1), 70% (AKI 2) and 69% (AKI 3) of cases (Table 2) (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Completion of diagnostic interventions for patients on recognition of AKI.

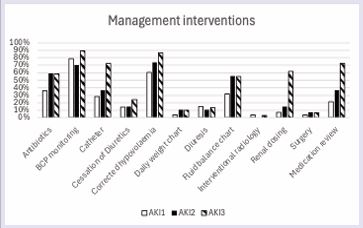

Management Interventions

Management practices varied with AKI severity; monitoring of fluid balance occurred in 32% (AKI 1), 56% (AKI 2) and 55% (AKI 3) of patients. Urinary bladder catheterisation was performed in 29% (AKI 1), 37% (AKI 2) and 72% (AKI 3) of cases. Correction of hypovolaemia was performed in 61% (AKI 1), 74% (AKI 2) and 86% (AKI 3) of cases. A medications review was performed in 21% (AKI 1), 37% (AKI 2) and 72% (AKI 3). Nephrology referral occurred most frequently among patients with AKI stage 3, with 45% discussed with renal services. Of those referred, 10% were subsequently accepted for transfer to a specialist renal ward. No referrals were made for patients with AKI stage 1, and nephrology involvement was documented in only 7% of AKI stage 2 cases (Table 2) (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Completion of management interventions for patients across AKI stages.

DISCUSSION

This review of the clinical management for patients with AKI in HUTH has seen an improvement in the recognition and documentation of AKI in the case notes. However, the data identifies significant areas requiring improvement across the domains of risk assessment, investigation and management of AKI. The UKKA guidelines recommend risk assessment and identification of inpatients at increased risk of AKI, so that preventative measures can be initiated including urine output monitoring and daily serum creatinine measurement [12]. By nature of this recommendation, the expectation in the data would be for all patients to have received risk factor assessment during their first medical review, such as co-morbidities, medications review, volume status and CKD status. Compliance with AKI risk factor screening on admission was generally lower for patients with AKI stage 1, either present on admission or developing later during the inpatient stay. This may reflect several factors. Patients presenting with or progressing rapidly to AKI stage 3 are often more clinically unwell, potentially prompting a more comprehensive review of risk factors such as hypovolaemia and sepsis. In a study exploring the rates of unrecognised AKI, it found that patients with unrecognised AKI were less likely to have shock as well as co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, when compared to patients with recognised AKI. A lower baseline serum creatinine on admission was also found to be associated with unrecognised AKI [13]. The thoroughness of risk assessment may also differ depending on whether AKI is present on admission or develops during the hospital stay. It remains unclear whether clinicians assess these factors specifically to prevent AKI, as many— such as comorbidities, medications, and biochemistry— are part of standard emergency department evaluation. Notably, factors like ‘urinalysis’ and ‘CKD status’ were rarely performed or documented on admission. For factors including ‘CKD status’, ‘hypotension’ and ‘hypovolaemia’, their low numbers may be in part explained by their absence in the clinical context and so not documented. However, given most sampled cases were community acquired AKI, the low frequency of urine testing suggests that risk assessment may not always be carried out with the intention of preventing onset or progression of AKI in mind.

Documentation of AKI has improved, with an overall compliance of 87% compared to 43% and 15% in 2018 and 2013 respectively [4-11]. However, the compliance with both local (Appendix 1) and national guidelines for investigating AKI remains suboptimal. This is particularly evident in the low rates of urine testing, where results could have prompted immunology investigations and earlier nephrology referrals in the presence of haematoproteinuria. The shortfall is especially striking given the number of patients who were catheterised, as in non-anuric cases this provides direct access to a urine sample. Only among patients with AKI stage 3 did just over half of patients undergo acid-base balance testing, urinary tract ultrasound and sepsis screening, with these interventions being performed in fewer than half with lower stage AKI. Urinalysis can inform on the aetiology of AKI and guide further, more specialist investigations, as well as aiding renal prognostication and predicting the need for renal replacement therapy (RRT).

A longitudinal study in Texas found that amongst patients admitted to hospital with Covid-19, those with any degree of haematuria or proteinuria on admission urine testing were more likely to develop AKI and were at higher risk of needing RRT [14]. Comprehensive investigation of AKI appears to only be considered for patients with more severe AKI, reflecting a reactive approach to care likely initiated when patients are more clinically unwell, as opposed to a proactive approach to investigate AKI appropriately whatever the clinical picture.

Management of AKI appears to be directed towards volume replacement. However, the findings indicate that in many cases this occurs without adequate fluid balance monitoring, thereby increasing the risk of inappropriate fluid administration and consequent fluid overload. The UKKA guidelines emphasise that intravenous fluids should not be routinely given to every patient with AKI, as well as highlight the use of diuretic therapy in patients whose renal hypoperfusion may be driven by congestion over hypovolaemia, such as those with heart failure and fluid overload [12]. The high rates of volume replacement (74%) in the absence of fluid balance monitoring (48%) raise the possibility that intravenous fluid therapy is being applied as a ‘blanket approach’ to AKI management, underscoring the need for enhanced clinician education regarding its underlying pathology.

A concerning finding is the broadly similar mortality rates across AKI stages, especially at 6 months, despite the literature conveying increased mortality with higher stage [1]. It begs the question whether the poor recognition and under-investigation of patients with lower stage AKI may lead to inadequate management, stage progression and poorer outcomes. A previous multi-centre retrospective cohort study found that, after adjusting for disease severity, documentation of AKI was associated with a reduced 30-day mortality (OR 0.81, 0.68-0.96, p = 0.02).Furthermore, these patients were more likely where indicated to receive volume replacement (64% vs 45%, p <0.001), cessation of their renin-angiotensin-aldosterone inhibiting medications (HR 2.04, 1.69-2.46, p <0.001) and a referral to nephrology (31% vs 6%, p <0.001) [15].

Other important aspects of AKI management, such as medications review with dose adjustments where appropriate, appear to be poorly implemented, particularly in patients with lower-stage AKI. Although Trust guidelines recommend renal referral for patients with AKI 3, this only occurred in 45%, suggesting limited awareness of the referral criteria for specialist input (Appendix 1). This may be further compounded by the under-investigation of AKI at the point of recognition, leading to missed diagnoses of intrinsic renal disease, which – if appropriately investigated – might have prompted nephrology referral.

While an association between the management of AKI and the discovered mortality rates cannot be concluded, the findings provide an essential reminder of the importance of comprehensive AKI assessment. Our results may suggest a deficiency of knowledge and confidence surrounding the assessment and management of AKI amongst clinicians, and a potential reluctance to act unless AKI presents in its more severe forms. This was similarly found in a study performed in Newcastle which found that, through anonymised questionnaires; 50% of trainees could not define AKI, 30% could not provide more than two risk factors for AKI and 37% could not recall an indication for nephrology referral [16]. Given that renal departments only provide care for 7% of all patients with AKI, the importance of clinician understanding of its management principles cannot be understated [17]. Improving the awareness and understanding of undergraduate and postgraduate medical professionals would be a tangible way of improving the quality of AKI care from what our findings present. At a national level, this could involve the production of simple AKI resources and care bundles based on the latest evidence such as the ‘ROUND-UP 26’ campaign produced by The Society for Acute Medicine (Appendix 2) [18]. At a local level, NHS Trusts should consider utilising such resources and ensuring their physical presence in clinical environments such that it is not difficult to access this guidance once it is required. Resident doctors will be familiar with the “DKA algorithm” drawer in the cabinet of their ward, similarly there should be a dedicated drawer for the “AKI algorithm” that can be easily reached for when required.

This study has several limitations. For risk assessment, it was assumed that if a factor was not documented, it had not been considered. However, in practice, normal findings are often omitted from documentation, which could have affected the results. The study was conducted in two hospitals within a single NHS Trust, and the findings may not be generalisable to AKI management practices across the wider NHS. Although discrepancies in AKI assessment and management were identified across severity stages, it was not possible to statistically evaluate their impact on patient outcomes. This study also did not differentiate between community-acquired and hospital-acquired AKI, an important variable for future research. Finally, whilst a telephone reporting system was introduced after the 2018 audit and prior to this study, it is not possible to determine whether observed changes in assessment and management were directly attributable to this intervention.

CONCLUSION

Although recognition of AKI has improved within our NHS Trust, significant variation remains in the thoroughness of risk assessment, investigation, and management based on AKI severity. We identify a need for improving clinician education in AKI risk assessment, investigation and management principles alongside the indications for specialist input. In the first instance we will increase awareness of and accessibility to the Trust’s AKI Care bundle within clinical environments. Our findings provide a useful baseline to improve upon as we continue to audit the quality of AKI care within HUTH.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MC: Participated in data collection and analysis, manuscript writing and approval of the final manuscript.

SSt: Participated in data collection and analysis, manuscript writing and approval of the final manuscript.

SSp: Corresponding author. Conceived study, participated in design and coordination. Manuscript writing and approval of the final manuscript.

RD: Conceived study, participated in design and coordination. Approval of the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012; 2: 1-138.

- Wonnacott A, Meran S, Amphlett B, Talabani B, Phillips A. Epidemiology and Outcomes in Community-Acquired Versus Hospital-Acquired AKI. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014; 9: 1007-1014.

- Finlay S, Bray B, Lewington AJ, Hunter-Rowe CT, Banerjee A, Atkinson JM, et al. Identification of risk factors associated with acute kidney injury in patients admitted to acute medical units. Clin Med. 2013; 13: 233-238.

- Hazara AM, Elgaali M, Naudeer S, Holding S, Bhandari S. The Useof Automated Electronic Alerts in Studying Short-Term Outcomes Associated with Community-Acquired Acute Kidney Injury. Nephron. 2017; 135: 181-188.

- National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. Adding insult to injury. A review of the care of patients who died in hospital with a primary diagnosis of acute kidney injury. London: National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. 2009.

- Hsu RK, Hsu CY. The Role of Acute Kidney Injury in Chronic Kidney Disease. Semin Nephrol. 2016; 36: 283-292.

- Mayer KP, Ortiz-Soriano VM, Kalantar A, Lambert J, Morris PE, Neyra JA. Acute kidney injury contributes to worse physical and quality of life outcomes in survivors of critical illness. BMC Nephrol. 2022; 23: 137.

- Mistry H, Abdelaziz TS, Thomas M. A Prospective Micro-costing Pilot Study of the Health Economic Costs of Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int Rep. 2018; 3: 1285-1293.

- Kerr M, Bedford M, Matthews B, O’Donoghue D. The economic impact of acute kidney injury in England. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014; 29: 1362-1368.

- NHS/PSA/D/2014/010: An NHS England Patient Safety Alert. 2014.

- Spencer S, Dickson F, Sofroniadou S, Naudeer S, Bhandari S, HazaraAM. The impact of e-alerts on inpatient diagnosis and management ofacute kidney injury. Br J Hosp Med. 2021; 82: 1-11.

- UK Kidney Association. National Acute Kidney Injury Summit: report and recommendations. London: UK Kidney Association. 2023.

- Han L, Li H, Luo L, Ye X, Ren Y, Xu Z, et al. Unexpectedly high rate of unrecognized acute kidney injury and its trend over the past 14 years. Sci Rep. 2025; 15: 6305.

- Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez B, Nieto-González L, Guerrero-Ramos F. Using dipstick urinalysis to predict development of acute kidney injury in patients with COVID-19. J Nephrol. 2022; 35: 345-353.

- Wilson FP, Bansal AD, Jasti SK, Lin JJ, Shashaty MG, Berns JS, et al. The impact of documentation of severe acute kidney injury on mortality. Clin Nephrol. 2013; 80: 417-425.

- Muniraju TM, Lillicrap MH, Horrocks JL, Fisher JM, Clark RM, Kanagasundaram NS. Diagnosis and management of acute kidney injury: deficiencies in the knowledge base of non-specialist, trainee medical staff. Clin Med (Lond). 2012; 12: 216-221.

- Selby NM, Crowley L, Fluck RJ, McIntyre CW, Monaghan J, Lawson N, et al. Use of electronic results reporting to diagnose and monitor AKI in hospitalized patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012; 7: 533-540.

- Society for Acute Medicine. Edinburgh: Society for Acute Medicine. 2023.