Current Management of Large B-Cell Lymphoma in Partial Remission: A Paradigm Change?

- 1. UOC Ematologia con Trapianto, Ospedale Monsignor R. Dimiccoli, Italy

Abstract

The treatment paradigm for large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) has undergone significant changes in recent years. Patients who fail to achieve a complete response (CR) after first-line therapy (1L) or relapse within 12 months are considered to have a poor prognosis. For these individuals, newer therapeutic options such as CAR-T cell therapy or immunoconjugates have largely replaced traditional approaches like chemotherapy, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (auto-HCT), or best supportive care. Accurate staging and evaluation of treatment response are critical, especially for patients achieving a partial response (PR) at the end of 1L. Patients with PR represent a distinct and less well-defined subgroup compared to those with stable or progressive disease or those achieving CR. These patients often have better outcomes than those with progressive disease or stable disease, yet their management remains less straightforward. Prognostic classifications and treatment guidelines continue to evolve, offering new perspectives on how best to approach this subset. While immunotherapy with anti-CD19 CAR-T cells has become the standard of care for refractory LBCL, the role of salvage therapies may still be relevant for patients with PR who are not fully chemorefractory. This review underscores the importance of refining the definitions, prognostic assessments, and therapeutic strategies for patients with partial response or early relapse, aiming to optimize outcomes in this challenging clinical context.

KEYWORDS

- Immunotherapy

- Hodgkin’s disease

- B-cell lymphoma

- CAR-T cell therapy

CITATION

Tarantini G, Arcuti E, Buquicchio C, Carluccio V, De Santis G, et al. (2025) Current Management of Large B-Cell Lymphoma in Partial Remis- sion: A Paradigm Change?. J Hematol Transfus 12(1): 1127.

INTRODUCTION

Since the last years of the last century, there has been a need for a standardization of the criteria for response to therapy of non-Hodgkin’ lymphomas (NHL) and Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The first universally accepted response criteria were published in 1999 [1]: these International Working group guidelines defined CR, partial remission (PR), complete remission unconfirmed (CRu), stable disease (SD), relapsed disease, and progressive disease (PD) based on physical examination , chest X-ray , computed tomography (CT) scan, single photon emission computed tomography gallium scans and visual bone marrow evaluation. In 2007, the availability of positron emission tomography (PET), immunochemistry and flow cytometry of the bone marrow, resulted in the revised guidelines [2]. Further experiences with the interpretation of PET scan results subsequently led to Lugano Classification for staging and response assessment incorporating PET CT as a standard component of both the staging and response assessment of FDG-avid histologies as Hodgkin’s disease, follicular lymphoma and large b-cell lymphoma (LBCL) [3]. One aim of these standardizations was a better interpretation of data and the comparisons of the results among various clinical data, but an accurate pretreatment evaluation and assessment of response are critical to the optimal management of patients with lymphoma. In this writing, therefore, we focus the assessment of response and the consequent decisions on management of patients with LBCL for which it has historically more complex to define: those in partial remission during or at the end of the first line and subsequent treatment.

In which prognostic category should patients in partial remission be considered?

- The best opportunity to cure LBCL lies in 1L. In 2001, L. Villela et al. analyzed the outcomes of LBCL patients who did not achieve CR with 1L regimens. The degree of response emerged as the only significant predictor of survival, with a 2-year survival rate of 40% for patients achieving PR. Historically, in 2002, the introduction of rituximab combined with chemotherapy became the new standard of care (SOC) [4]. Despite this advancement, a significant proportion of patients remained refractory or relapsed (R/R). Adding rituximab to cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) as a 1L regimen negatively impacted the outcomes of second-line (2L) treatment in R/R patients. In 2006, Suleyman Alici et al. conducted a retrospective study to identify prognostic factors specifically predicting survival in LBCL patients who did not achieve CR after 1L therapy. They reported a median overall survival (OS) of 17.8 months in patients with PR. Univariate analysis identified response to initial therapy (primary refractory disease or PR, P= .005) as a significant prognostic factor, while multivariate analysis confirmed that response to initial therapy (P =.009) independently influenced OS. Although patients with primary refractory disease had a poor prognosis, those achieving PR had slightly better outcomes [5]. In 2014, Rovira et al. assessed 816 LBCL patients who did not achieve CR or experienced relapse, both before and after rituximab use. In this study, PR patients accounted for 7% of the cohort and demonstrated better responses to salvage therapy and outcomes compared to primary refractory patients. Historically, patients in PR after 1L therapy have often been grouped with relapsed LBCL patients in clinical trials [6]. Three Phase 3 comparative studies conducted in the rituximab era—CORAL (R-DHAP vs. R-ICE), ORCHARRD (ofatumumab vs. rituximab), and LY.12 (R-GDP vs. R-DHAP) [7-9]-focused on identifying optimal salvage regimens for patients eligible for autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (auto- HCT). These studies reported overall response (OR) rates ranging from 29% to 46% in refractory patients or those relapsing within 12 months of frontline therapy but did not specifically stratify PR patients after 1L. Similarly, the SCHOLAR-1 study, which stratified PR patients only after salvage therapy and auto-HCT, found that patients with refractory disease (stable or progressive disease despite four cycles of 1L therapy, or two cycles of subsequent- line therapy, or relapse <12 months post-auto-HCT) had a 1-year OS rate of 26% [10]. Refractory disease after 1L therapy is consistently associated with poor outcomes.

The lack of chemosensitivity has been repeatedly identified as an adverse prognostic factor in LBCL patients [6,4]. Historically, these patients were treated with salvage chemotherapy followed by consideration for auto-HCT. However, in contrast to the PARMA protocol [11], which included patients in second PR or CR after salvage therapy, more recent analyses from the European Blood and Marrow Transplantation Registry included only patients achieving CR due to the adverse prognosis associated with chemorefractory disease. The concept of chemosensitivity, therefore, is crucial and should be determined based on response to 1L therapy in LBCL patients. LBCL cases that fail to respond adequately to 1L treatment or relapse early after initial immunochemotherapy are considered "primary refractory disease" and have poor outcomes. Definitions of primary refractory disease vary in the literature. Narrow definitions include failure to achieve PR or CR after 1L therapy, while broader definitions encompass treatment failure or relapse within 12 months of completing immunochemotherapy1. This definition has become more relevant following the results of three clinical trials—ZUMA-7, BELINDA, and TRANSFORM [12]—which randomized primary refractory patients to receive CAR-T therapy versus SOC (salvage therapy + auto-HCT). Notably, both ZUMA-7 and TRANSFORM demonstrated improved OS in the CAR-T arm. There is no consensus among lymphoma specialists regarding the definition of early treatment failure. Studies such as CORAL and CIBMTR identified refractory disease or relapse within 12 months of diagnosis as unfavorable, while the ZUMA-7, BELINDA, and TRANSFORM trials, along with LY.12, defined high- risk patients as those with refractory disease or relapse within 12 months of completing frontline therapy. To clarify the definition of primary refractory LBCL, A.M. Bock et al. [13] proposed categorizing these patients into three groupStable or progressive disease (PD) during or by the end of 1L therapy, including transient interim PR or CR, and primary PD (PPD).

- PR as the best response at the end of treatment (EOT PR).

- Early relapse within 3, 3–6, or 6–12 months after achieving CR at the end of 1L therapy.

In their study, two cohorts were analyzed: 949 patients (MER) and 2,755 patients (LEO). Among these, 132 (13.9%; PPD = 40, EOT PR = 40, early relapse = 52) and 308 (11.3%; PPD = 145, EOT PR = 66, early relapse = 97) patients met inclusion criteria for primary refractory disease, respectively. The 2-year OS rates were 30% for PPD, 50% for EOT PR, and 58% for early relapse, with PPD patients showing significantly worse outcomes compared to the other two groups. Based on these results, primary refractory LBCL was defined as stable or PD during or by the EOT (PPD group). Patients with inadequate responses (EOT PR) and early relapse had similar outcomes and may be better grouped as early relapse.

The CAR-T as second-line (2l) option for LBCL patients

As previously mentioned, recent pivotal trials evaluating CAR-T therapy as a 2L option for patients with primary refractory or early relapsed (within 12 months) LBCL—ZUMA-7 [14], TRANSFORM [15], and BELINDA [16]—compared axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel), lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel), and tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel), respectively, with salvage chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) [17]. The analysis of overall survival (OS) data from the ZUMA-7 trial demonstrated a survival benefit for axi-cel over ASCT, with the median OS not reached in the axi- cel group versus 31.1 months in the comparator arm. In the TRANSFORM trial [15], the median OS was also not reached for the liso-cel group compared with 29.9 months in the ASCT arm, whereas the BELINDA trial failed to meet its primary endpoint [16]. Both ZUMA-7 and TRANSFORM highlighted the superiority of CAR-T therapy in this high-risk population, leading to the inclusion of CAR-T as a 2L option in the NCCN guidelines for patients with primary refractory disease or relapse within 12 months of completing 1L therapy. The primary endpoint for all three trials was event-free survival (EFS), although the definitions of EFS varied. All trials included disease progression and death as events, along with lack of complete or partial response (stable disease) at a designated time point. These time points differed, being longest in ZUMA-7 at 150 days compared to 9 weeks in TRANSFORM and 12 weeks in BELINDA. In these trials, refractory disease was defined as the absence of CR following 1L therapy, while relapsed disease was defined as CR followed by biopsy-proven disease recurrence within 12 months of completing 1L therapy. It is important to emphasize that determining disease refractoriness is crucial for risk stratification in LBCL. As highlighted by Locke et al., patients with PR at the end of treatment (EOT) represent a distinct prognostic category with outcomes better than those of primary progressive disease (PPD) but worse than those of patients achieving CR [14]. In CAR-T studies, patients with PR after 1L therapy are not always distinguished from refractory patients. In the TRANSFORM trial, 39% of patients in the liso-cel group and 49% in the SOC group had PR as the best response to 1L therapy. In ZUMA-7, these patients were not differentiated from the primary refractory group. In the ALYCANTE trial [18], a Phase II study in which 62 transplant-ineligible patients were treated with axi-cel as 2L therapy, 16% of patients had PR as their best response to 1L therapy [14].

In the PILOT [19], a phase 2 trial in which 61 patients not intended for ASCT received liso-cel , 25% of them were in PR as best response to 1L therapy. Real-world data from the DESCAR-T registry [20,21], a French nationwide registry of all patients treated with approved CAR-T therapies, showed that 26.2% of LBCL patients treated with axi-cel in 2L had PR as their disease status before CAR-T infusion. However, in the CAR-T SIE study [22], an Italian real-world multicenter observational study on CAR-T therapy for LBCL and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), stratification of LBCL patients in PR after 1L therapy was not performed.

The patient in partial remission in the current guidelines

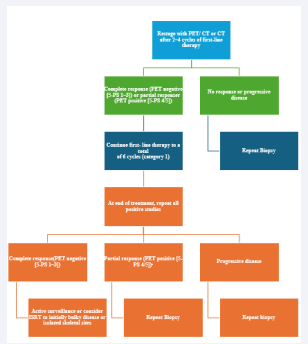

The current criteria for assessing response to therapy in NHL are based on the Lugano Classification of 2014 [3]. A PET-CT–based partial metabolic response in lymph nodes and extra lymphatic sites is defined as a Deauville score (DS) of 4 or 5, with reduced uptake compared to baseline and residual masses of any size. However, there is a distinction between such results at interim PET scans, where they indicate a responding disease, and at end-of- treatment PET scans, where they are considered residual disease. In the bone marrow, residual uptake greater than that in normal marrow but reduced compared to baseline is also considered significant. Persistent focal changes in the marrow within the context of a nodal response should prompt further investigation, such as MRI, biopsy, or interval scans. The evaluation of lymph nodes, residual masses, and bone marrow therefore involves a quantitative approach, primarily assessing FDG uptake reduction compared to baseline as a key parameter. According to Cheson et al.[3], a score of 4 or 5 at interim PET scans suggests chemotherapy-sensitive disease when uptake has reduced from baseline and is classified as a partial metabolic response. At the end of treatment, residual metabolic disease with a score of 4 or 5 is regarded as treatment failure, even when there is a reduction in uptake from baseline. A score of 4 or 5 with unchanged or increased intensity compared to baseline, or the presence of new foci compatible with lymphoma, indicates treatment failure at both interim and end-of-treatment assessments. In 2025, during the era of second-line CAR-T therapy for LBCL, updated guidelines were published for managing LBCL by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [23] and the British Society of Hematology (BSH) [24]. The NCCN guidelines [23] (figure 1,figure 2) categorize patients based on disease stage,

Figure 1: Management Stage I–II (smIPI 0–1; BULKY; ≥7.5 CM) (Excluding Stage II with Extensive Mesenteric Disease) RESTAGING AND ADDITIONAL THERAPY According to NCCN 2025. NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 5-PS, PET Five-Point Scale; SMIPI: Stage-Modified International Prognostic Index; RCHOP, Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Prednisone, Rituximab and Vincristine; PET: Positron Emission Tomography; ISRT: Involved Site Radiation Therapy; PR: Partial Response

Figure 2: Management Stage I–II with Extensive Mesenteric Disease OR Stage III–IV Disease Restaging and Additional Therapy According to NCCN 2025, NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 5-PS, PET Five-Point Scale; PET: Positron Emission Tomography; ISRT, Involved Site Radiation Therapy; PR: Partial Response

distinguishing between stages I/ II (excluding stage II with extensive mesenteric disease) and advanced stages, including stage II with extensive mesenteric disease, stage III, and stage IV. For patients with stage I/II disease, interim PET is performed after three to four cycles of R-CHOP, with three possible response outcomes: complete response, progressive disease, and partial response. Patients in partial response, defined by positive interim PET with a DS of 4, are recommended to undergo repeat biopsy. If the biopsy is negative, the treatment pathway follows the complete response pathway. No specific recommendation is provided for cases with positive biopsies, but it is implied that continuation with an additional two to three cycles of R-CHOP, with or without ISRT, would be necessary. For advanced stages, including stage II with extensive mesenteric disease, stage III, and stage IV, interim PET is conducted after two to four cycles of R-CHOP. While three response outcomes are possible, the guidelines consolidate complete and partial responses into the same pathway, with progressive disease in a separate pathway. Patients in partial response with a DS of 4 or 5 on interim PET continue therapy until six cycles of R-CHOP are completed. At restaging, if the DS is still 4 or 5, a repeat biopsy is performed. A positive biopsy at this stage confirms refractory disease. For patients with a DS of 4 in advanced stages, brief interval restaging should be considered, as this result may represent either active disease or a post-treatment inflammatory response. The BSH guidelines [24] (figure 3)

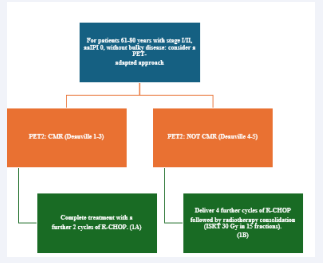

Figure 3: 2024 Recommendations for Management Stage I and II Disease According to British Society of Hematology RCHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, prednisone, rituximab and vincristine PET: Positron Emission Tomography; ISRT: Involved Site Radiation Therapy; PR: Partial Response; AAIPI: Age-Adjusted International Prognostic Index; CMR: Complete Metabolic Response

propose a PET-adapted approach specifically for patients aged 61–80 years with stage I/II disease, IPI 0, and no bulky disease. These patients undergo interim PET after two initial cycles of R-CHOP. If a complete metabolic response (CMR) is achieved with a DS of 1–3, treatment is completed with an additional two cycles of R-CHOP. For patients without CMR, defined by a DS of 4 or 5, four additional cycles of R-CHOP are administered, followed by radiotherapy consolidation. A change in treatment is only recommended for patients with no response or progressive disease on interim PET. At the end of treatment, patients with CMR on interim PET generally require only a CT scan for end-of-treatment imaging. For patients without CMR or those who did not undergo interim PET, an end-of-treatment PET-CT scan is recommended, typically three to six weeks after the final dose of antibody. Residual FDG-avid foci warrant biopsy wherever feasible. If biopsy is not possible and imaging findings remain inconclusive, a repeat PET scan after an interval of eight to twelve weeks is advised.

DISCUSSION

Until a few years ago, the standard treatment for patients with R/R LBCL was high-dose chemotherapy followed by ASCT. This approach was based on the premise that treatment resistance could be overcome by administering higher doses of chemotherapy. However, it has since become clear that ASCT in chemo-insensitive disease is largely futile, with a response to salvage therapy being a necessary prerequisite to proceed with transplantation. In recent years, the therapeutic landscape for R/R LBCL has evolved, and the status of lymphoma at the time of receiving salvage treatment has become a crucial prognostic factor. Patients with primary refractory disease rarely respond to second-line therapies, with the SCHOLAR-1 meta-analysis showing response rates of 17% for PR and 3% for CR [10]. Additionally, early relapse patients tend to have worse outcomes than those with late relapse. Today, high-risk patients have access to new alternative treatment options, no longer limited to clinical trials or best supportive care.

One significant development is the emergence of chemo-free therapies, such as CAR-T cell therapy, immunoconjugate antibodies which have provided promising alternatives to chemotherapy [25]. These new options have highlighted the importance of detecting the lack of chemosensitivity, as identifying this early could prevent the unnecessary and potentially harmful administration of further chemotherapy. This shift in treatment paradigm has led to a change in how we classify and approach relapsed patients. Patients who relapse more than one year after initial therapy are now considered chemosensitive and should be considered for ASCT if eligible. Conversely, those who relapse within a year of completing initial therapy are candidates for second-line CAR-T cell therapy if eligible, marking immunotherapy as the new standard of care for patients with refractory LBCL.

In this context, defining partial remission accurately at the right time in a patient's clinical journey is critical. The 2025 guidelines from the NCCN and the BSH offer strategies for patients with LBCL in partial remission, particularly for stages I and II. According to the NCCN guidelines, patients in partial remission after 3-4 cycles of R-CHOP with a DS of 4 at interim PET should undergo biopsy to determine whether to pursue the CR or PR pathway. If biopsy results are negative, the CR pathway can be followed. The BSH guidelines, on the other hand, suggest that patients aged 61-80 years with DS 4 or 5 at interim PET (without comparing uptake to baseline) should proceed with four additional cycles of R-CHOP followed by radiotherapy, without performing a biopsy. For all other patients, the negative predictive value for interim PET is about 80%, with studies showing that only a small percentage of PET- negative patients experience positive end-of-treatment PET scans.

For patients who achieve a CMR on interim PET (iPET2), BSH recommends a CT scan for end-of-treatment imaging. For those without CMR on iPET2, or those who did not undergo an iPET2, a PET-CT scan should be performed. Similarly, the NCCN guidelines recommend end-of- treatment PET for patients in stages I/II (PR pathway) and stages III/IV (CR/PR pathway). If DS is 4 or 5, a repeat biopsy should be performed, or clinical judgment should be used if biopsy is not possible. Both sets of guidelines emphasize the importance of waiting a few weeks to assess the response, with BSH recommending eight weeks after the last dose of antibody, and the NCCN recommending a brief interval in cases with a DS of 4, as this may reflect post-treatment inflammation rather than active disease.

This timing is crucial, as there are significant barriers to the timely delivery of CAR-T therapy in clinical practice. Patients often undergo weeks or months of eligibility and fitness assessments, CAR-T manufacturing, and logistical planning. Some patients experience symptomatic, life- threatening progressive disease before receiving CAR-T and require urgent chemotherapy as bridging therapy. The time from decision to infusion, known as "brain-to- vein" time, is a critical factor. This period, along with pre- apheresis therapies that may affect the health or CAR-T cell manufacturing process, could impact outcomes [26]. As such, it may be more useful to focus on the "brain-to- vein" time as a better indicator of CAR-T treatment success, rather than the traditional "vein-to-vein" time.

Beyond the guidelines, there are still significant challenges as well as the setting of patients who arrive at transplant or CAR.T therapy after demonstrating a response (CR or PR) to salvage chemo-immunotherapy: may they do well with auto HCT consolidation? Could this option at least be discussed with patient?

Patients who relapse within the first year of completing chemoimmunotherapy and achieve a CR with platinum- based salvage therapy can benefit from high-dose chemotherapy (HDT) and ASCT [27]. Two studies showed that high-dose therapy and auto-HCT consolidation is curative for approximately 45% of patients with LBCL despite achieving only a PR after salvage therapy [28,29]. On the other hand, patients considered CAR-T candidates often receive bridging chemotherapy before CAR-T therapy, with some achieving a response, including CR. The three trials ZUMA-7, BELINDA and TRANSFORM were not designed to address the management of LBCL patients in PR responsive to salvage therapies and excluded patients who received any second-line treatment. This raises the question of whether it would have been more appropriate for CAR-T trials to treat all patients with salvage chemotherapy before randomizing them, as most patients with prior therapy exposure may have less potent CAR-T products.

Recent retrospective studies have examined patients with LBCL in PR after salvage therapy treated with either ASCT or CAR-T cell therapy. One such study found that patients in PR who underwent ASCT had a similar PFS but a lower relapse risk and superior OS compared to those receiving CAR-T. These results support the role of auto- HSCT for transplant-eligible patients and suggest that for some patients, ASCT may be a reasonable first option, particularly if they have already responded to salvage chemotherapy. Other studies have shown that patients with chemosensitive disease, even those with primary refractory or early relapsed disease, can achieve durable disease control with ASCT consolidation.

In a study comparing ASCT and CAR-T in patients aged over 65 with chemosensitive R/R LBCL in PR after salvage chemotherapy [30,31], the results showed similar PFS and OS at one year, with no significant difference between the two therapies. However, CAR-T therapy was associated with lower non-relapse mortality (NRM) compared to ASCT, particularly in high-risk subgroups. These findings support CAR-T as a viable option for older adults with chemosensitive disease and suggest that CAR-T may be preferable for fit older patients with relapse beyond one year.

Howewer, it must be taken into account that all these retrospective studies have expected bias and among these the authors considered the definition of PR to be an important limitation: the interpretation of PR and diagnostic modality varied among institutions especially in the non-clinical trial setting.

In conclusion, although CAR-T therapy became the new standard of treatment for patients who not reach a CR after 1L and early relapsed, ASCT could still be an important treatment option for patients who achieve a response to salvage chemotherapy [32]. The decision between ASCT and CAR-T should be based on patient characteristics, including age, comorbidities, and response to prior therapies. As clinical practice continues to evolve, a personalized approach to treatment is critical, with careful consideration of the timing and type of therapy used to maximize patient outcomes.

CONCLUSION

As highlighted by the results of several retrospective studies, the definition of PR remains inconsistent across various clinical settings, despite ongoing efforts at classification and standardization, culminating in the Lugano Classification of 2014. This variability in the interpretation of PR is particularly crucial in the context of managing patients with R/R LBCL, especially when considering the treatment decisions for those in PR following frontline therapy. This challenge becomes even more significant when managing patients with refractory disease, where the clinical decision-making landscape has evolved substantially.

Recent guidelines, however, recommend repeating a biopsy in cases of suspected partial remission based on interim or end-of-treatment PET uptake and associated DS for advanced stages, and after interim PET for stage I/II patients.

The current treatment paradigm for R/R LBCL patients takes into account the timing of recurrence (within 12 months or after 12 months), which influences whether the disease is considered chemosensitive. For patients who relapse within 12 months (early relapsed), the prognosis is generally poor and the disease is often regarded as chemo- resistant. However, for those in PR after first-line R-CHOP therapy, considered primary refractory, the management approach remains nuanced. While their prognosis aligns with that of early relapsed patients, some retrospective studies suggest that their disease may not be completely chemo-insensitive. This observation forms the basis for considering caution in routinely offering CAR-T treatment to all patients; for those under 65 years of age salvage therapies followed by ASCT, particularly when timely access to CAR-T therapy is challenging.

The growing body of evidence suggests that a subset of patients in PR after salvage therapy could still benefit from ASCT, potentially leading to durable disease control. Nevertheless, to comprehensively address the management of LBCL in PR following salvage therapy, which was excluded in the design of the three major CAR-T trials, and to explore further the comparative effectiveness of ASCT versus CAR-T in patients with chemosensitive disease, the design of randomized trials could be a logical next step. This would help clarify the optimal therapeutic approach for this patient population and potentially refine existing treatment guidelines

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Conflict of interest: Giuseppe Tarantini has received a speaker honorarium from Takeda, Roche, Beigene, Abbvie, Elena Arcuti declares that she has no conflict of interest, Caterina Buquicchio declares that she has no conflict of interest, Vera Carluccio declares that she has no conflict of interest, Gaetano De Santis declares that he has no conflict of interest, Candida Rosaria Germano declares that she has no conflict of interest, Mariangela Leo declares that she has no conflict of interest, Daria Loconte declares that she has no conflict of interest, Sonia Mallano declares that she has no conflict of interest, Rosanna Maria Miccolis declares that she has no conflict of interest, Teresa Maria Santeramo declares that she has no conflict of interest, Vanda Strafella declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

REFERENCES

- Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, Shipp MA, Fisher RI, Connors JM, et al. Report of an International Workshop to Standardize Response Criteria for Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 1999; 17: 1244- 1244.

- Cheson BD, fistner BP, Juweid ME, Gascoyne RD, Specht L, Horning SJ, et al. International Harmonization Project on Lymphoma. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25: 579-86.

- Cheson, B. D, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, Cavalli F, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, et al. Recommendations for Initial Evaluation, Staging, and Response Assessment of Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: The Lugano Classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014; 32: 3059-3067.

- Vilella L, López-Guillermo A, Montoto S, Rives S, Bosch F, Perales M, et al. Prognostic features and outcome in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who do not achieve a complete response to first- line regimens. (2001).

- Alici S, Bavbek S, Basaran M, Onat H. Prognostic factors in patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma without complete response to first-line therapy. Adv. Ther. 2006; 23: 534-542.

- Rovira J, Valera A, Colomo L, Setoain X, Rodríguez S, Martínez-Trillos A, et al. Prognosis of patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma not reaching complete response or relapsing after frontline chemotherapy or immunochemotherapy. Ann. Hematol. 2015; 94: 803-812.

- Van Den Neste E, Schmitz N, Mounier N, Gill D, Linch D, Trneny M, et al. Outcomes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients relapsing after autologous stem cell transplantation: an analysis of patients included in the CORAL study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52: 216-221.

- Van Imhoff GW, McMillan A, Matasar MJ, Radford J, Ardeshna KM, Kuliczkowski K, et al. Ofatumumab Versus Rituximab Salvage Chemoimmunotherapy in Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: The ORCHARRD Study. J Clin Oncol. 2017; 35: 544-551.

- Crump M, Kuruvilla J, Couban S, MacDonald DA, Kukreti S, Kouroukis CT, et al. Randomized Comparison of Gemcitabine, Dexamethasone, and Cisplatin Versus Dexamethasone, Cytarabine, and Cisplatin Chemotherapy Before Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation for Relapsed and Refractory Aggressive Lymphomas: NCIC-CTG LY.12. J C O. 2014; 32: 3490-3496.

- Crump M, Neelapu SS, Farooq U, Van Den Neste E, Kuruvilla J, Westin J, et al. Outcomes in refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the international SCHOLAR-1 study. Blood. 2017; 130: 1800-1808.

- Philip T, Chauvin F, Bron D, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, Coiffier B, et al. PARMA international protocol: Pilot study on 50 patients and preliminary analysis of the ongoing randomized study (62 patients). Ann. Oncol. 1991;2: 57-64.

- Bommier C, Lambert J, & Thieblemont C. Comparing apples and oranges: The ZUMA-7, TRANSFORM and BELINDA trials. Hematol. Oncol. 2022;40: 1090-1093.

- Bock AM, Chauvin F, Bron D, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, Coiffier B, et al. Defining Primary Refractory Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) Based on Survival Outcomes. Hematol. Oncol. 2023; 41: 430-432.

- 14. Locke FL, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, Miguel-Angel P, Marie-José K, Oluwole OO, et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel as Second-Line Therapy for Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022; 386: 640-654.

- Abramson JS, Solomon SR, Arnason J, Johnston PB, Glass B, Bachanova V, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel as second-line therapy for large B-cell lymphoma: primary analysis of the phase 3 TRANSFORM study. Blood 2023; 141: 1675–1684.

- Bishop MR, Dickinson M, Purtill D, Barba P, Santoro A, Hamad N, et al. Second-Line Tisagenlecleucel or Standard Care in Aggressive B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022; 386: 629-639.

- Perales M-A, Anderson Jr LD, Jain T, Kenderian SS, Oluwole OO, Shah GL, et al. Role of CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells in Second- Line Large B Cell Lymphoma: Lessons from Phase 3 Trials. An Expert Panel Opinion from the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy. Transplant Cell Ther. 2022; 28: 546-559.

- Houot, R, Bachy E, Cartron G, Gros F-X, Morschhauser F, Oberic L, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel as second-line therapy in large B cell lymphoma ineligible for autologous stem cell transplantation: a phase 2 trial. Nat Med. 2023; 29: 2593-2601.

- Sehgal A, Hoda D, Riedell PA, Ghosh N, Hamadani M, Hildebrandt GC, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel as second-line therapy in adults with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma who were not intended for haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (PILOT): an open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2022; 23: 1066-1077.

- Broussais F, Bay JO, Boissel N, Baruchel A. DESCAR-T, le registre national des patients traités par CAR-T Cells. Cell. À Récepteur Antigénique Chimérique CAR-T Anticorps Bispécifiques. 2021; 108: S143–S154.

- Brisou G, Cartron G, Bachy E, Thieblemont C, Castilla-Llorente C, Le Bras F, et al. Real World Data of Axicabtagene Ciloleucel As Second Line Therapy for Patients with Large B Cell Lymphoma: First Results of a Lysa Study from the French Descar-T Registry. Blood. 2023; 142: 5138-5138.

- Stella F, Chiappella A, Casadei B, Bramanti S, Ljevar S, Chiusolo P, et al. A Multicenter Real-life Prospective Study of Axicabtagene Ciloleucel versus Tisagenlecleucel Toxicity and Outcomes in Large B-cell Lymphomas. Blood Cancer Discov. 2024; 5: 318-330.

- NCCN 2024. B-Cell Lymphomas. (2025).

- Fox CP, Chaganti S, McIlroy G, Barrington SF, Burton C, Cwynarski K, et al. The management of newly diagnosed large B-cell lymphoma: A British Society for Haematology Guideline. Br J Haematol. 2024; 204: 1178-1192.

- García-Sancho AM, Cabero A & Gutiérrez NC. Treatment of Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: New Approved Options. J Clin Med. 2023; 13: 70.

- Lunning M. Autologous and Allogeneic CAR T-Cell Therapies: Spotlighting the “Brain-to-Vein” Time.

- Shargian L, Amit O, Bernstine H, Gurion R, Gafter-Gvili A, Rozovski U, et al. The role of additional chemotherapy prior to autologous HCT in patients with relapse/refractory DLBCL in partial remission-A retrospective multicenter study. Eur J Haematol. 2023; 110: 149-156.

- Sauter CS, Matasar MJ, Meikle J, Schoder H, Ulaner GA, Migliacci JC, et al. Prognostic value of FDG-PET prior to autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2015; 125: 2579-2581.

- Shah N, Ahn KW, Litovich C, He Y, Sauter C, Fenske TS, et al. Is autologous transplant in relapsed DLBCL patients achieving only a PET+ PR appropriate in the CAR T-cell era? Blood. 2021; 137: 1416– 1423.

- Akhtar OS, Cao B, Wang X, Torka P, Al-Jumayli M, L. Locke F, et al. CAR T-cell therapy has comparable efficacy with autologous transplantation in older adults with DLBCL in partial response. Blood Adv. 2023; 7: 5937-5940.

- Westin JR, Locke FL, Dickinson M, Ghobadi A, Elsawy M, Meerten TV, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Axicabtagene Ciloleucel versus Standard of Care in Patients 65 Years of Age or Older with Relapsed/Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2023; 29: 1894-1905.

- Shadman M, Pasquini M, Ahn KW, Chen Y, Turtle CJ, Hematti P, et al. Autologous transplant vs chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for relapsed DLBCL in partial remission. Blood. 2022; 139: 1330-1339.IA