Multisensory Full-Body Training for Stroke Children: The Case of Climbing

- #. M. Gori and S. Basta contributed equally to this work

- 1. Unit for Visually Impaired People, Italian Institute of Technology, Genoa, Italy

- 2. Institute for Human & Machine Cognition (IHMC), 40 South Alcaniz St. Pensacola, USA

- 3. University of Genoa, Department of Informatics, Bioengineering, Robotics and Systems Engineering, Genoa, Italy

- 4. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Unit, IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Genoa, Italy

- 5. EDL – Electronic Design Laboratory, Italian Institute of Technology, Genoa, Italy

- 6. MWS-Manufacturing and Design Facility, Italian Institute of Technology, Genoa, Italy

INTRODUCTION

Pediatric stroke causes significant morbidity for children and can lead to lifelong neurological disability. Morbidities among pediatric stroke survivors include motor and sensory deficits, language impairment, behavioral problems, and epilepsy.

Evidence shows that timely rehabilitation intervention is essential to exploit neuroplasticity, which is highest in the first months. Most interventions focus on recovering motor and sensorimotor skills, but they tend to be strictly operator dependent. Some protocols rely on non standardized or non-validated scales and questionnaires, evidence-based practice protocols, or non-technological devices.

What is often missing is the integration of rehabilitation interventions with quantitative measurements based on the child’s sensory and motor state. New technologies should adapt to the child’s activity by providing sensory stimuli appropriate to the specific condition. Technology that incorporates sports or physical activity and entertainment tailored to individuals would be more beneficial than existing solutions.

The current review combines the joint knowledge of neuroscientists, engineers, and rehabilitators. We present the state of the art in multisensory processing and rehabilitation in pediatric stroke, focusing on both the classic rehabilitation approach and today’s technologies for climbing. Finally, we propose guidelines to develop more usable technologies capable of producing quantifiable benefits.

Grounded in intelligent technology, this paper suggests that combining multisensory skills with physical activities can improve engagement in pediatric rehabilitation for children with pediatric stroke. In the next section, we present current data and impairments related to pediatric stroke.

Pediatric Stroke: Incidence,Outcome and Multisensory Impairments

Stroke is one of the most frequent causes of child disability in developed countries. Pediatric stroke is typically divided into perinatal stroke (between 20 weeks of gestational age and ≤ 28 days old) and childhood stroke (29 days to 18 years old), due to differences in etiology, risk factors, presentation, and outcomes between the two age groups [1]. The estimated incidence of stroke is between one in 1600 and one in 3000 live births (neonatal) and 5.6 per 100,000 children [2-4].

Pediatric stroke survivors are at high risk of lifelong disability of varying severity and complexity, including motor, proprioceptive, language, cognitive, or behavioral deficits, as well as neurological sequelae such as post-stroke epilepsy [5]. These disabilities require individualized pathways of care [6], demanding extensive resources and support networks.

Recovery after a stroke largely depends on the plastic properties of the brain [7]. While post-stroke plasticity has received significant scholarly attention in adults [8-10], mainly focused on the motor system, plasticity mechanisms and implications for rehabilitation in children likely differ and remain poorly understood [11]. Early brain damage affects normative development, leading to a lack of accomplishment of developmental milestones [12]. However, critical and sensitive periods during brain development offer “windows of opportunity” for neuro modulatory interventions, during which the developing brain can particularly benefit [13].

Accordingly, individualized long-term care must be tailored to children’s developmental stages and their physical, psychological, and social contexts, while also considering the severity of residual neurological deficits. These may result in activity limitations, reduced cognitive and communicative abilities, and medical comorbidities [14]. The extreme clinical variability and complexity of affected functions determine multifaceted skill development [14]. Although rehabilitation often focuses on motor function, this is not typically the only impaired domain after pediatric stroke; multisensory impairment is also common.

Somatosensory impairment frequently follows pediatric stroke, significantly contributing to motor disability and essentially determining the degree of recovery [15,16]. In adults, 45–80% of stroke patients experience somatosensory impairment, which is strongly associated with motor and functional deficits [17, 18]. Despite this clinical relevance, there is no consensus on how to assess proprioceptive deficits or on specific rehabilitation strategies [19].

Post-stroke visual impairment can be multifactorial. Visual field loss (hemianopia) is the most common symptom, followed by abnormal eye movements, reduced visual acuity, diplopia, impaired color vision, and higher order visual deficits such as hemispatial neglect. Since vision plays a central role in many human functions, its reduction can strongly affect the quality of life, motivation, and social behaviors [1].

The central vestibular system may also be directly compromised, particularly in patients with a posterior stroke [20]. Although rarely associated with hearing impairments [21], decreased use of vestibular end-organs, caused by compromised motor abilities, may lead to their underdevelopment [22].

Furthermore, not only can different sensory modalities be impaired, but difficulties in sensory integration are also widely reported after stroke. About one-third of adult stroke patients show impairment in multisensory integration, particularly those with lesions in the left hemisphere, left basal ganglia, and brainstem/cerebellar regions [23]. Recent research suggests that targeting neural circuitry involving spared motor regions across hemispheres through neuromodulation and multimodal sensory stimulation can improve rehabilitation in adults [24-26]. However, far less is known about these mechanisms when stroke occurs in pediatric populations [27].

In the next section, we discuss the importance of multisensory and sensorimotor processing and training during development in children.

4.2. The Importance of Multisensory and Sensory Motor Training in Children

The human brain receives multiple sensory signals from sight, hearing, and touch as a person interacts with their environment throughout the day. Recent studies indicate that when more sensory signals are available, the brain integrates this information to improve perception derived from such signals [28,29].

However, this multisensory integration process is not always immediate, and it develops relatively late for certain tasks [30,31]. For example, the ability to integrate audio visual information about the spatial relationship between stimuli or the visual-tactile dimension develops only after 8–10 years of age [30,32-34]. By contrast, other abilities, such as sound localization, seem to improve reaction times and precision when accompanied by a sound from the first months of life [32].

An interesting process that appears in late integration cases is cross-modal calibration [30,35]. This process allows information to transfer between senses, guiding the development of one sensory modality from a reference one. For instance, studies confirm that the tactile modality is fundamental in calibrating the visual modality regarding object size [30]. Therefore, children with motor disabilities may have difficulties visually understanding the size of objects that they cannot physically explore [34]. This highlights the importance of understanding multisensory mechanisms in children with pediatric and perinatal stroke, as well as how alternative sensory signals can provide support.

Closely related to the multisensory theme is sensorimotor integration. During each movement, touch moves with the body, while vision observes the body in motion. The sensory feedback derived from one’s movement in space is fundamental for building a functional body representation in space [36]. This development begins around five months of age, when infants start recognizing their body visually, an essential milestone for understanding that the body can be used as a tool to act in space [36].

This association is compromised when either motor or visual signals are absent or deficient. However, recent studies show that new associations can emerge when one sensory signal replaces another. For example, acoustic signals linked to body movements can restore body and space perception in visually impaired children [37-39], with positive effects also observed in children with motor disabilities [40].

Since stroke is often associated with perceptual and sensory impairments, little is known about multisensory deficits and the benefits of new sensory-motor associations in these children. Nevertheless, multisensory processing and sensorimotor integration demonstrate how alternative and integrative signals can facilitate interaction with the body, others, and rehabilitation devices. For example, the ABBI device, which uses audio feedback for motor activation, has been successfully applied in cases of visual loss [37-39] and can be adapted to motor impairments [40]. Beyond restoring functions, multisensory processing has been shown to improve accuracy, speed, and precision of responses [29].

This evidence suggests that using multiple sensory signals could be especially beneficial for children with stroke. Therefore, the development of new technologies should integrate these principles to create practical, accessible, and effective tools based on multisensory perceptual and motor foundations. The next section explores how current rehabilitation approaches combine multisensory and sensorimotor signals, often without the use of specific technological devices.

Full-Body Rehabilitation in Pediatric Stroke: State of the Art

The mainstay of pediatric stroke treatment has so far relied on rehabilitation to improve outcomes and support the child during development and skills acquisition. Although effective rehabilitative treatment approaches for pediatric stroke are available, little is known about optimal rehabilitation strategies and the unique interplay between the developing brain, injury, and available models of stroke recovery.

To date, the available studies mostly focus on motor outcomes, specifically on upper limb functioning. Cognitive and language outcomes are even more difficult to predict. Moreover, researchers have widely studied the rehabilitation of motor impairments in children with cerebral palsy. Cerebral palsy covers a variety of medical conditions, including perinatal stroke early in life, but not stroke later in childhood.

Overall, evidence supports using Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT), Hand-arm Bimanual Intensive Therapy (HABIT), repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, functional electrical stimulation, and robotics. The strength of evidence varies for the different types of treatment and age groups. Building on consolidated experience in adults, several studies have confirmed the usefulness of upper limb intensive training during the pediatric age, particularly in the application of CIMT and HABIT.

More recently, efforts have been made to create adapted protocols for increasingly early interventions in preschool children, toddlers, and even infants (< 12 months of age). The results of these studies showed that intensive rehabilitation is feasible in young children and provided moderate-level evidence concerning the efficacy of these two modalities in children with hemiparesis.

HABIT-Including Lower Extremity (HABIT-ILE) applies motor skill learning and intensive training to both the upper and lower extremities. HABIT-ILE involves constantly stimulating both the body’s extremities through combined activities for many hours each day over a period of two weeks. This rehabilitation approach improves motor function in school-aged children with unilateral cerebral palsy.

HABIT-ILE has shown improvements in post-stroke hemiparesis across the three domains of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).

To our knowledge, there are no significant studies on the use of technological devices in pediatric and perinatal stroke rehabilitation protocols specifically targeting multisensory integration (MSI). Despite the growing interest in pediatric stroke rehabilitation, very little is known about post-rehabilitation functional, neuroplastic, and biomechanical changes during the developmental age.

From a global and not purely motor perspective, adapting validated adult protocols may be suboptimal. These observations highlight the need for new motor rehabilitation protocols designed as multisensory and fun activities. Such programs should aim to improve strength, endurance, postural stability, technique, balance, coordination, route finding, attention, and address several psychological aspects.

Combining Full-Body Activities and Multisensory Stimulation as a Key in Rehabilitation

A question emerges regarding how one can combine multisensory processing and rehabilitation.

MSI in humans has received significant attention from researchers who have provided insights into the neural underpinnings [23]; however, as of 2025, only a few studies are available regarding MSI at a behavioral level in adults with acquired brain damage [41].

Scientific evidence of the importance of multisensory stimulation associated with sensorimotor rehabilitation in children is mainly focused on high-risk newborns [42-44]. In this population, it is well-known how both structural and functional alterations interfere with normal sensory processing and environmental exploration, leading to sub optimal sensorimotor experiences [45]. These are the basis of cognitive, motor and social long-term development, which are essential to building a coherent perception of the world, a foundation for learning and social interactions [46]. Using kangaroo care, infant massage, and environmental enrichment in neonatal intensive care units are some examples of early multisensory-based rehabilitation approaches [4,47,48].

Among older children, the interaction between neural networks and environments deeply influences brain development and function, including sensory stimuli, early stress, parental-child as well as peer relationships [49]. These can be lacking in children with disabilities [50]. Multisensory interventions, associated with sensorimotor rehabilitation, often in occupational therapy settings, allow more complex, articulated experiences resulting in adaptive responses with the full potential of circuitry development. These multisensory-based rehabilitation approaches support processing and sensory integration as facilitators that increase skills and exploit the child’s motivation (i.e., enhancing tactile, proprioceptive, and vestibular experiences) [51].

The effectiveness of multisensory stimulation as a possible rehabilitation method after stroke has been investigated in adults with a focus on both low-level, perceptual (visual, auditory, and somatosensory deficits) [52], as well as higher-level, cognitive, sensory deficits [53]. Current multisensory stimulation methods employed in post-stroke rehabilitation include motor imagery, action observation, mirror therapy or virtual environment, and music therapy [54].

Multisensory stimulation (mainly visual-proprioceptive and audio-visual stimulation) can recruit and strengthen residual pathways in the brain after acquired brain lesions [52]. Indeed, it may restore sensory performance and function alongside long-term effects [55].

Most existing studies in pediatric settings have focused on including augmented reality [15], environmental enrichment, ecological activities such as child-initiated movement/active motor learning, and home programs [56].

The next paragraph presents a novel approach to combine the neuroscientific findings on multisensory processing and the knowledge of classical rehabilitation with recent technological advancements. In doing so, we propose the activity of climbing as an innovative approach to combining these three aspects.

Climbing as a Full-Body Rehabilitation in Pediatric Stroke

One might consider what we know about climbing, as well as how we might improve climbing and sensory and motor abilities through multisensory climbing rehabilitation.

Climbing therapy (CT) has been investigated for many pathologies in adults, such as lower back pain [57], multiple sclerosis [58], cerebellar ataxia [59] and, more recently, in the pediatric population (summarized in the next subparagraph). Available studies presented several limitations and risk of bias due to methodological limitations, such as limited access to data, different evaluation tools, or insufficient sample size for statistical measurements [60].

Specifically, three studies have discussed therapeutic climbing for children with CP, including patients with perinatal stroke [61-63], while there are no identifiable studies involving children with pediatric stroke. Overall, these studies involved 26 children with CP (average age 11.26) who presented with mild to moderate functional disability (Gross Motor Function Classification System I III) [64], while the study excluded children with severe cognitive and motor impairment.

The main parameters analyzed before, during, and after the period of CT related to motor function as upper limb strength, gait function or spasticity control. In one study, the engagement of children was also evaluated, showing that following the period of training, most children expressed a wish to continue climbing [63]. Overall, these studies suggested a positive impact on motor competence and peer socialization.

Despite initial promising data on the possible therapeutic role of climbing at pediatric ages, there remains a lack of standardized protocols, including integrative protocols with physiotherapy or stretching. Furthermore, one must consider possible adverse events or contraindications, as specified in a recent study that suggests a critical discussion about the use of CT for children with CP due to the risk of improving crouch gait [61].

Children with pediatric stroke or CP lack experience in sensory motor activities due to their neuromotor deficits, and they tend to show a variety of multisensory impairments [15,20-22]. A recent paper has reported how sport, due to its known benefits on the motor, cognitive, and relational components, can work within this population as an important therapeutic instrument to actively involve children in sensory-motor activities, as well as improve psychological health and relationships with peers [65].

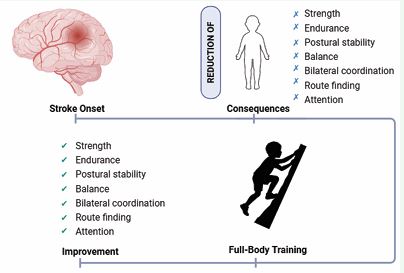

In particular, sport climbing involves strength, endurance, and postural stability [66], balance, bilateral coordination, route finding [67], and attention [68]. This evidence may suggest that rock climbing in a rehabilitation setting can also improve extension against gravity, flexion extension alternation, anticipation and planning of the movements. Furthermore, a rich sensory-motor activity, like climbing, can support the dynamic sensory-motor process and act as the catalyst for development [69].

Therapeutic climbing is a playful and interactive activity calibrated to the specific skills and sensory needs of children, allowing those with stroke and CP to engage in a just-right challenge. It has also brought out an adaptive response, which is the basis of learning. Finally, augmentative feedback can be useful during significant sensory-motor activities for motor re-learning [70] (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The figure provides an overview of the improvements achieved through a full-body multisensory training, highlighting its positive impact on strength, endurance, postural stability, balance, bilateral coordination, route finding, and attention.

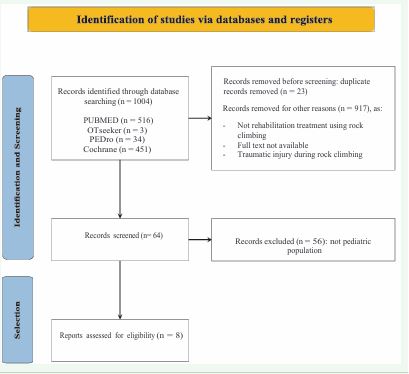

All the methodology used for screening and selecting the studies included in this review, including inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as the overall selection process, is presented in Figure 2. The literature search was completed in September 2025.

Figure 2 Identification of studies via database.

SUMMARY OF STUDIES ABOUT THE USE OF THERAPEUTIC ROCK CLIMBING WITH CHILDREN

Kong D et al. [71], investigated the therapeutic effects of rehabilitation climbing wall training combined with brain computer interface (BCI) in 100 adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients (AIS), aged from 13 to 18 years. Participants were randomly assigned to a control group (rehabilitation climbing wall training) and an observation group (BCI-assisted climbing wall training). Patients underwent 3 months of training. The results showed significant improvements in spinal curvature angle, known as Cobb angle, lumbar range of motion, lumbar function, and quality of life in both groups, with the observation group (BCI) showing significantly greater gains. The total effective rate was also higher in the BCI group (96% vs. 82%). These findings suggest that BCI-assisted rehabilitation climbing wall training is clinically effective for AIS patients and may offer a non-invasive alternative to surgery. Nevertheless, further research is needed to confirm long-term effects.

Däggelmann [72], explored the role of exercise and physical activity to improve endurance and strength as part of usual rehabilitation care for childhood cancer survivors. The aim of the study was to evaluate the feasibility and beneficial effects of a 10-week indoor wall climbing intervention in 11 childhood cancer survivors (aged 6–21 years) after cessation of medical treatment. The results showed beneficial potential for physical functioning. However, some clinical preconditions, like close supervision, must be ensured.

Schram Christensen [63], conducted a 9-session indoor climbing intervention over three weeks involving 11 children with cerebral palsy and 6 typically developing children aged 11–13 years. The study assessed physiological, psychological, and cognitive outcomes and found improvements in climbing abilities in both groups. Children with cerebral palsy showed significant gains in the Sit-to-stand and pinch tests of the least affected hand, while no changes were observed in cognitive abilities or psychological well-being.

Böhm et al. [61], evaluated the effect of climbing therapy on gait function in eight children and adolescents with bilateral spastic cerebral palsy (mean age 13.0 ± 4.3) in a randomized, controlled crossover trial. Participants received six weeks of conventional physiotherapy followed by climbing therapy, or vice versa. Both interventions improved some Gait Profile Scores, suggesting potential benefits of climbing therapy on crouch gait.

Koch et al. [62], investigated therapeutic climbing in seven children with cerebral palsy (mean age 9.6 ± 3.7) over 19 sessions in three months. Significant improvements were observed in right handgrip strength, postural control, and functional mobility, highlighting climbing as a feasible intervention.

Lee and Song [73], conducted a case study on a 7-year old child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, examining the effects of four weeks of therapeutic climbing while wearing a weighted vest. Improvements were found in mean alpha wave activation and attention span measured with EEG and the Star Cancellation Test.

Mazzoni et al. [74], assessed the effect of indoor wall climbing on self-efficacy and self-perceptions in 46 children with special needs (6–12 years). The term special needs referred to students with heterogeneous diagnoses that included motor function difficulties. Children participated in a six-week program once a week, resulting in significant improvements in self-efficacy, while athletic and social competence remained unchanged. The authors suggested that longer training periods and specialized adapted programs should be explored.

Therme and Soulayrol [75], explored learning and behavior modulation in six psychotic and borderline children (mean age 6 ± 10 months) through indoor climbing. Quantitative and qualitative analyses indicated increased engagement, climbing time, and success rate over six sessions, reflecting notable learning improvements in a short period.

MULTI-SENSORY FEEDBACK TECHNOLOGIES: AN OVERVIEW

The best technological solutions one might use to create a new multisensory integrated rehabilitation system based on climbing are worthy of discussion. To identify technologies to promote cross-modal integration of sensory systems, in this section, we provide a non exhaustive overview of existing non-invasive technological solutions one can use to achieve multi-sensory feedback.

To provide multi-sensory feedback, a device needs input about the current state of the system. Following that, it must compare the current state with the desired state and finally give its output correctly. All those steps are equally important in giving multi-sensory feedback and will be addressed in this section.

Getting Input from the User

The first step is that of acquiring the state (either kinetic and kinematic or both) of the user performing the task.

A 2007 review [76], classifies human tracking systems in visual (requiring a video camera), non-visual (using various sensors placed on the body), and robotic-aided (using both input and output devices). Tracking sensors have been classified as either wearable or non-wearable [77].

For full-body rehabilitation, we will classify input devices based on whether they require a sensor to be placed on the user’s body (wearable devices), if they require contact between the user and an external device, or if they can do everything remotely. Wearable devices include Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs, usually composed of accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers) and EMG (Electromyography) [78-81]. These proved to be reliable gait assessment methods in stroke rehabilitation [82-84]. For a detailed description of technologies and future improvements, see Sethi et al., [85]. For a recent systematic review of the use of those technologies in post stroke rehabilitation, see Boukhennoufa et al. [86].

Input devices can also sense the contact between the user and an external object. This can be done in simple ways (e.g., by using a push-button), but an everyday life example could be the touch screen of a smartphone. The same kind of sensors (either resistive or capacitive) can be mounted on other objects to track the contact points or surfaces between the user and the object. Another more expensive way to track the contact is by using force sensors. These can be realized with different technologies but have the advantage of allowing an estimation of the contact force between the subject and the external object.

Zhou and Hu [76], note that another tracking method is the use of external robots, used extensively in stroke rehabilitation [87,88]. Loureiro et al. [89], compared different kinds of robots used for upper-limb rehabilitation and their connections to the human body.

It is also possible to track the body position without contact with the subject in various ways. By using ultrasounds, infrared, or laser ToF, one can determine the distance of the body from a reference point. The same technology is used in depth-sensing cameras like the commercially available Microsoft® Kinect to extract the body’s position; this has been used extensively in rehabilitation [90]. Other optic sensors include laser range scanners (LRS) and cameras (with or without markers placed on the subject). One can also remotely extract the body position by exploiting electromagnetic (EM) field interaction with the human body. One example is the use of UltraWideBand radar to continuously track the position of body limbs during an activity [91,92]. For a systematic review of the technologies used for stroke rehabilitation at home, see Chen et al. [93].

Sending Output to the User

Multi-sensory feedback depends on the ability to provide stimuli in multiple sensory modalities, leading to organizing output devices based on the sensory modality they stimulate. Among the senses humans use to perceive the world, vision and hearing are the most exploited in the technology used in everyday life, with simple LEDs and buzzers included in most domestic appliances as of 2023. Given the permeating use of smartphones, game console controllers, and, more recently, fitness bracelets and smartwatches, the use of vibrotactile haptic feedback is increasing.

Vision: The simplest, cheapest, and power-efficient way to stimulate human vision using electronic components is an LED. Each LED can emit light on a fixed wavelength; one can combine them into an RGB system to produce light, which is perceived as various colors by the human eye. As usage examples, an LED can be used near a label to signal that an event occurred, placed behind a translucent object, or placed in a matrix to display text or images.

Electronic displays are other devices that can commonly provide feedback. Various display technologies are currently available. Displays are a simple and cost-effective way of providing visual feedback and creating a virtual reality (VR) that one can employ for rehabilitation [94,95]. Similar to electronic displays, image projectors can be used to display images, where an image can be projected over other surfaces like walls, floors, or even the body itself [96].

While the technology used in head-mounted displays [97], is the same as that of standard displays, they can be used to create immersive VR [98], but special care is required to avoid motion sickness [99]. Nevertheless, those devices have been used in post-stroke rehabilitation [100].

Hearing: Electroacoustic transducers are devices that can produce audible sound vibrations. To produce a simple tone, a piezoelectric buzzer is appropriate, while loudspeakers can be used for more complex sounds. Depending on the number and the location of the speakers, it is possible to create more complex environments, like spatialized sounds [101], which may be simulated using stereo headphones [102], by using the phase and volume difference between the two channels.

Bone-conducting headsets can also produce audible sound vibrations. Compared to standard headphones, these do not occlude the ear canal, thus allowing one to perceive other external sounds.

Haptic: A simple and cheap way of providing haptic feedback is by using vibrotactile stimulators, technology regularly employed by smartphones, game console controllers and fitness bands. Force-feedback devices and actuated systems (robotic devices) can provide more complex force-feedback to the user. It is also possible to provide haptic feedback without requiring contact between the user and a device. Those “contactless” [103] haptic feedback use air (either with air jets or with ultrasonic sounds) to stimulate the user’s skin.

Combining Multiple Sensory Stimulations: The midbrain combines information coming from multiple senses [104], and integrates them into a coherent representation [105]. Multimodal feedback – sometimes referred to as multisensory feedback – is the use of feedback coming from multiple sensory modalities simultaneously. Using feedback in multiple sensory modalities immersion increases the sense of presence in virtual environments [106].

The effect of multimodal feedback has been studied in different kinds of learning environments, as the use of multiple sensory feedback in motor learning [107], with great efficacy, considered the best way to combine them; depending on the complexity of the movement, one must learn. Multimodal stimulation also appeared to be more effective in stroke recovery [108].

From a technological standpoint, VR headsets are a good example of multimodal feedback, where the user receives stereo visual feedback, audio, and vibrotactile stimulation via the handheld controllers.

Climbing Technologies

There are various kinds of technological solutions currently available for supporting climbing. Some of these projects, along with the kind of inputs and outputs used, have been summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Various commercial and research projects trying to enhance climbing by using different kinds of technologies, sorted alphabetically.

|

Project Name |

Description |

Inputs |

Outputs |

|

Ouchi et al. |

Record the physical behavior of children |

Strain gauge force sensor in each hold |

Transparent holds with LED lights |

|

Vähämäki |

Real-time climbing pose estimation |

Depth sensing camera for motion tracking |

NA |

|

ACCEPT |

Adaptive climbing wall, sensorized and reconfigurable, optimized for children with cerebral palsy |

3 Axis Force Sensor in each hold, IMU on smart bracelet |

NA |

|

Arcade Climbing |

Help climbers of all levels move, play, and train |

Force Feedback (“when pulled”) in each hold |

Partially transparent holds with LED lights |

|

Clift Climbing |

Motivate climbers |

Contact (“track every grip and step”) |

LED lights |

|

ClimbLing |

Improve indoor climbing experience with new challenges |

Capacitive Touch in each hold |

Transparent holds with LED lights |

|

Digiwall |

Introducing climbing to new users, promoting physical activity |

Touch sensors in each hold |

7 loudspeakers |

|

Edge |

Training wall for climbers |

Pressure sensors in each hold |

Vibrotactile bracelets, transparent holds with LED lights and Sound Speakers |

|

EverActive |

Adjustable climbing wall |

NA |

LED lights below each hold |

|

Grasshopper |

Adjustable climbing wall |

NA |

NA |

|

GreenGrip |

Develop materials for climbing holds |

NA |

NA |

|

Kilter Board |

Provide boulder problems from an online database, on an adjustable-angle wall |

NA |

Transparent holds with LED lights |

|

MoonBoards |

Optimize climbing performances with a standardized bouldering training wall |

NA |

LED light below each hold |

|

SpectrumSports |

RGB LED grips for climbing walls |

NA |

Transparent holds with LED lights |

|

Tracktion |

Climbing Video Game |

Capacitive Touch in each hold |

Transparent holds with LED lights, display behind the climbing wall |

|

ValoClimb |

Fully automatic attraction |

Some form of motion tracking |

Video Projector, Speakers |

They differ both regarding the aim and the technologies used. Some simply focus on the building blocks of a sensorized climbing wall, such as GreenGrip, which develops climbing holds that diffuse light made with new, sustainable materials, or Grasshopper, which produces reclinable climbing walls.

The majority of currently available systems are commercial, but some examples are also available in scientific literature. For example, Ouchi et al. [109], aims to study the physical behavior of playing children to improve the safety of playgrounds. Vähämäki [110], uses a depth sensor to estimate the climbers’ pose. Two projects developed a climbing wall from scratch [111], aimed at combining climbing with computer games, using sound and music as sensory feedback to replace the screen, and using the user’s contact with the climbing holds as an input device. The ACCEPT project also developed a sensorized climbing wall aimed at the rehabilitation of children with cerebral palsy [112].

When considering these systems’ inputs and outputs, it is possible to see that the most used kind of output given is visual: most of those projects use LED lights near or below the climbing holds. In the ValoClimb system[113,114], a projector beams video content on the climbing wall. Instead, in the Tacktion system, the climbing wall has transparencies that show displays mounted behind it. Three projects provide audio feedback by using two or more speakers.

The input from the user is obtained in different ways: seven projects have sensors that detect the contact between the holds and the user, two of which also sense the contact force by using force sensors in each climbing hold; two other projects use camera-based motion tracking to estimate the position of the body. The interest in climbing wall technologies might be driven by the increased interest in indoor climbing, a market that is increasing roughly 10% annually.

DISCUSSION

Input For Future Developments: How Can We Improve Sports/Climbing Tools for Children with Motor Disabilities?

On a Neuroscientific Level: We believe that three main aspects can be improved on a neuroscientific level:

(1) Rehabilitation technologies for stroke children should be multisensory to facilitate integration. First, as the introduction discusses, motor disability brings with it not only impairments related to motor aspects but also related to other sensory aspects, such as the sensory and perceptual ones. The possibility of understanding these mechanisms and intervening with multisensory stimulation can provide excellent rehabilitation support. For example, one can integrate vision with sound by considering associations in our perceptual system.

This might improve the deficit associated with visual size processing highlighted in children with motor impairment. One example is the visual size and sound size association provided by cross-modal matches: low sounds are associated with large dimensions and high-pitched sounds with small dimensions. This simple acoustic signal could be included in evaluating the size of the objects to facilitate their interaction. In the climbing example, holds of different sizes can play with low and high sounds to enable preparation for the grip. Similarly, a sensory signal associated with movement, such as a sound, could help the child with motor disabilities control their movement and interact with the instrument or other children. Climbing could allow an enriched sensory experience. Augmented feedback (i.e., on the tactile-auditory system) can stimulate the development of other systems (i.e., to better identify the position of hands and better understand the spatial reference).

(2) Rehabilitation technologies for stroke children should be adaptable to the needs and characteristics of the individual and, therefore, flexible. Many sensory characteristics change during development in the typical child. These differences are even more marked in a child with stroke who can have various motor, cognitive, and sensory problems. We believe that a second important point to consider in developing new technologies is to create adaptable and flexible systems for each child’s individuality and rehabilitation period. This can happen thanks to the development of intelligent systems based on decoding sensory or motor inputs that produce feedback adapted to the child’s sensory, cognitive, and motor needs. Artificial intelligence and ML applied to technological solutions might offer new possibilities in this direction.

(3) Rehabilitation technologies for stroke children should be validated, in comparison with a control group, to demonstrate their effectiveness. Very often, technologies are developed without being scientifically validated. Effective intervention should produce a measurable improvement in behavior and possibly also in cortical neuroplasticity. As we have seen, there is an optimal intervention window for a child with stroke to obtain better results. This window must be exploited with adequate technology; that technology must be scientifically validated with quantitative methods. This would benefit both the user (e.g., improvement in the quality of life) and scientific knowledge (e.g., quantified validations would allow studying of the cortical mechanisms underlying the change).

On a Clinical Level: From a clinical point of view, we identified three other main aspects requiring improvement:

(1) To develop standardized rehabilitation protocols for the use of climbing in clinical practice. The limited number of studies available in the literature on therapeutic climbing in pediatric age does not allow one to define a priori the optimal rehabilitation protocol according to the type of patient, motor impairment and therapeutic aims. Moreover, the studies systematically excluded children with severe cognitive and motor impairment. The use of advanced technologies and the applicability of therapeutic climbing in a hospital setting could allow activities to include children with severe disabilities.

(2) To identify the parameters that are most likely to be changed through therapeutic climbing as an alternative or combined therapy to the rehabilitative standard of care. The main parameters analyzed before, during and after the period of CT in CP related to motor function as upper limb strength, gait function, Range of Motion or spasticity control. However, based on the experience gained by applying therapeutic climbing in adults or different pediatric conditions, it is reasonable to think that positive results may appear in different areas such as self-esteem, peer socialization and engagement. Only the definition of standardized assessment tools and scales before, during and after rehabilitation protocols will lead to the real effectiveness of climbing training in all these areas. This permits the conditions necessary to lay the theoretical foundations for using therapeutic climbing not only in the rehabilitation of pediatric stroke but also in many other conditions. The use of specific technological devices may allow one to obtain a standardized outcome and thereby provide the best standard of care.

(3) To evaluate the impact of enriched activity on the sensorimotor experience, reducing the lack of experience typical of children with sensorimotor damage. Children with stroke or CP can experience a limitation in motor, cognitive and praxis skills due to sensory processing impairment. This can result in a lack of sensorimotor experiences, learning delays and reduction of social interaction with peers, as well as accessibility and independence in self care or play skills. The intrinsic features of climbing, or Sensor-Embedded Climbing with advanced technologies, can both enrich sensory experience and improve sensory motor ability. This could represent an effective tool for reducing the gap experience between typically developed children and those with stroke or CP, depending on their limited mobility and cognitive, sensory perceptual and fine motor skill deficits.

On a Technological Level: (1) Conveying information from the technology solution. Providing multisensory feedback is insufficient for deciding which kinds of information in a sensory modality can be conveyed in multiple ways. Using sound as an example, basic physical properties like frequency and amplitude can be modulated, but it is also possible to produce rhythmic sounds (beeps with different duty cycles and frequencies), or even by using natural sounds or speech [115]. Depending on personal preferences, impairments and age, different output properties can be manipulated, as it is important to tailor the activity to the needs of children involved.

From an electrical system-level viewpoint, one of the key features that enables both data collection to make therapy decisions and quantify the performance of climbing is the flexibility of the implemented device. The design must be suitable for research purposes and enable scientific exploration. Electronic systems can now include a wide variety of sensors and actuators, and a single Printed Circuit Board (PCB) can contain a heterogeneous collection of components. In this respect, the system can embed a sensor fusion.

Each sensor has a very strict functionality; they sharply sense a limited number of physical quantities, and it is not generally possible to increase the number of sensors above a certain limit. The limit is intrinsic in the components’ technology. A large quantity of data needs to be processed to assess the status of the user: even at low frequency, the sampled quantities from a large number of climbing rods can constitute a large amount of data, and its transmission to a central node for processing. This requires effective partitioning of the network. Data must be processed in real time with a maximum latency of 20 ms [116]. The design of each climbing rod must be effective to decrease the quantity of information transmitted using pre-processing or intelligent signaling mechanisms and sensor configuration. Electronics need to be co-designed with the mechanics to fully exploit the form factors made available by the climbing holds. Because the climbing rods need to sustain a significant weight, one must carefully plan the positioning of the electronics within the holds. In the case of touch detection, different approaches can be applied based on capacitive sensing, inductive sensing, light sensing, and infrared sensing. Among these technologies, the most flexible and overall low-cost is infrared, largely because sensors can be deployed according to a spatial configuration that can only be devised based on the form of the hold without having to intervene on its surface mechanical features, as it would be required to functionalize the surface of the hold using suitable substrates and electrodes. The use of surface-based touch detectors would increase the complexity of the wiring, the mechanics of the hold, and consequently cost. Moreover, such solutions would imply the use of more sophisticated technologies, thereby severely impacting the production cost.

(2) Software. Software plays an important role in providing appropriate feedback. To outperform the limitations of the above-described electronics, sensor fusion can be improved by using ML on the sampled sensor data by first training the network using a sufficiently large statistical dataset. This can be acquired thanks to the flexibility given by the research-oriented design of the device. This constructed dataset can be designed on purpose and can regard the interaction of the human while climbing with one or more sensors in different operating conditions. A well-trained neural network can open the way to achieve increased performance with conventional and standardized hardware. It can be deployed, depending on its complexity, both on micro-controlled systems and on general-purpose computers. The possibility of intervening in the firmware or software in the system at many levels of abstraction enables on-demand reprogramming. It also opens the way to being able to provide suitable feedback on patients and improved climbing training sessions for patients. Moreover, assuming a more powerful scheme, ML can be even more personalized based on a continuously evolving dataset to sharpen the experience of the user and improve data collection during a session.

CONCLUSIONS

To conclude, very little is known about post rehabilitation functional, neuroplastic and biomechanical changes during developmental age in pediatric stroke. In this review, we described the importance of multisensory processing, and we proposed new motor rehabilitation protocols and technologies that can provide multisensory fun activities improving motor, cognitive, and psychological aspects in young children with stroke.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by AstraZeneca Italia and On behalf of the SPort hoSPital Group: Alice Tramonti, Paolo Granone, Matteo Mordeglia, Francesca Invrea, Carla Ferrari, Mattia Beltrami, Ambra Zuffi, and Sofia Fiscon.

REFERENCES

- Ferriero DM, Fullerton HJ, Bernard TJ, Billinghurst L, Daniels SR, DeBaun MR, et al. Management of stroke in neonates and children: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019; 50: 51-96.

- Kirton A, Andersen J, Herrero M, Nettel-Aguirre A, Carsolio L, Damji O, et al. Brain stimulation and constraint for perinatal stroke hemiparesis: The PLASTIC CHAMPS Trial. Neurology. 2016; 86: 1659-1667.

- Laugesaar R, Kolk A, Tomberg T, Metsvaht T, Lintrop M, Varendi H, et al. Acutely and retrospectively diagnosed perinatal stroke: a population-based study. Stroke. 2007; 38: 2234-2240.

- Nithianantharajah J, Hannan AJ. Enriched environments, experience- dependent plasticity and disorders of the nervous system. Nature Reviews Neurosci. 2006;7: 697-709.

- deVeber GA, MacGregor D, Curtis R, Mayank S. Neurologic outcome in survivors of childhood arterial ischemic stroke and sinovenous thrombosis. J Child Neurol. 2000;15: 316-24.

- Malone LA, Felling RJ. Pediatric stroke: unique implications of the immature brain on injury and recovery. Pediatric Neurol. 2020; 102: 3-9.

- Kornfeld S, Delgado Rodríguez JA, Everts R, Kaelin-Lang A, Wiest R, Weisstanner C, et al. Cortical reorganisation of cerebral networks after childhood stroke: impact on outcome. BMC Neurol. 2015; 15: 90.

- Bütefisch CM. Plasticity in the human cerebral cortex: lessons from the normal brain and from stroke. The Neuroscientist. 2004; 10: 163- 1673.

- Plow EB, Cunningham DA, Varnerin N, Machado A. Rethinking stimulation of the brain in stroke rehabilitation: why higher motor areas might be better alternatives for patients with greater impairments. The Neuroscientist. 2015; 21: 225-240.

- Starkey ML, Schwab ME. How plastic is the brain after a stroke? The Neuroscientist. 2014; 20: 359-371.

- Woodward K, Carlson H, Kuczynski A, Saunders J, Hodge J, KirtonA. Sensory-motor network functional connectivity in children with unilateral cerebral palsy secondary to perinatal stroke. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2019; 21: 101670.

- Abgottspon S, Steiner L, Slavova N, Steinlin M, Grunt S, Everts R. Relationship between motor abilities and executive functions in patients after pediatric stroke. Applied Neuropsychology: Child. 2022; 11: 618-628.

- Ismail FY, Fatemi A, Johnston MV. Cerebral plasticity: Windows of opportunity in the developing brain. Eur J Paediatric Neurol. 2017; 21: 23-48.

- Trabacca A, Vespino T, Di Liddo A, Russo L. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for patients with cerebral palsy: improving long-term care. J Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2016; 22: 455-462.

- Kuczynski AM, Semrau JA, Kirton A, Dukelow SP. Kinesthetic deficits after perinatal stroke: robotic measurement in hemiparetic children. J Neuroengineering Rehabilitation. 2017; 14: 13.

- Zandvliet SB, Kwakkel G, Nijland RH, van Wegen EE, Meskers CG. Is recovery of somatosensory impairment conditional for upper-limb motor recovery early after stroke? Neurorehabilitation Neural Repair. 2020; 34: 403-416.

- Klingner CM, Witte OW, Günther A. Sensory syndromes. Front NeurolNeurosci. 2012; 30: 4-8.

- Meyer S, De Bruyn N, Krumlinde-Sundholm L, Peeters A, Feys H, Thijs V, et al. Associations between sensorimotor impairments in the upper limb at 1 week and 6 months after stroke. J Neurol Physical Therap. 2016; 40: 186-195.

- Findlater SE, Dukelow SP. Upper extremity proprioception after stroke: bridging the gap between neuroscience and rehabilitation. J Motor Behav. 2017; 49: 27-34.

- Ekvall Hansson E, Pessah-Rasmussen H, Bring A, Vahlberg B, PerssonL. Vestibular rehabilitation for persons with stroke and concomitant dizziness—a pilot study. Pilot and feasibility studies. 2020; 6: 146.

- Winstein CJ, Stein J, Arena R, Bates B, Cherney LR, Cramer SC, et al. Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/ American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2016; 47: e98-e169.

- Torok N, Perlstein MA. III Vestibular Findings in Cerebral Palsy. Ann Otology Rhinol Laryngol. 1962; 71: 51-67.

- Van der Stoep N, Van der Stigchel S, Van Engelen RC, Biesbroek JM, Nijboer TCW. Impairments in Multisensory Integration after Stroke. J Cogn Neurosci. 2019; 31: 885-899.

- Alwashmi K, Meyer G, Rowe FJ. Audio-visual stimulation for visual compensatory functions in stroke survivors with visual field defect: a systematic review. Neurol Sci. 2022; 43: 2299-321.

- Hakon J, Quattromani MJ, Sjölund C, Tomasevic G, Carey L, Lee J-M, et al. Multisensory stimulation improves functional recovery and resting-state functional connectivity in the mouse brain after stroke. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2018; 17: 717-30.

- Teo WP, Muthalib M, Yamin S, Hendy AM, Bramstedt K, Kotsopoulos E, et al. Does a combination of virtual reality, neuromodulation and neuroimaging provide a comprehensive platform for neurorehabilitation?–a narrative review of the literature. Front Human Neurosci. 2016; 10: 284.

- Bortone I, Leonardis D, Solazzi M, Procopio C, Crecchi A, Bonfiglio L, et al, editors. Integration of serious games and wearable haptic interfaces for Neuro Rehabilitation of children with movement disorders: a feasibility study. ICORR. 2017.

- Alais D, Burr D. The ventriloquist effect results from near-optimal bimodal integration. Current Biol. 2004; 14: 257-262.

- Ernst MO, Banks MS. Humans integrate visual and haptic information in a statistically optimal fashion. Nature. 2002; 415: 429-433.

- Gori M, Del Viva M, Sandini G, Burr DC. Young children do not integrate visual and haptic form information. Curr Biol. 2008; 18: 694-698.

- Nardini M, Bales J, Mareschal D. Integration of audio-visual information for spatial decisions in children and adults. Dev Sci. 2016; 19: 803-816.

- Gori M, Campus C, Cappagli G. Late development of audio-visual integration in the vertical plane. Curr Res Behav Sci. 2021; 2: 100043.

- Gori M, Sandini G, Martinoli C, Burr D. Poor haptic orientation discrimination in nonsighted children may reflect disruption of cross- sensory calibration. Curr Biol. 2010; 20: 223-225.

- Gori M, Tinelli F, Sandini G, Cioni G, Burr D. Impaired visual size-discrimination in children with movement disorders. Neuropsychologia. 2012; 50: 1838-1843.

- Gori M. Multisensory integration and calibration in children and adults with and without sensory and motor disabilities. Multisensory Res. 2015; 28: 71-99.

- Bremner AJ, Mareschal D, Lloyd-Fox S, Spence C. Spatial localization of touch in the first year of life: early influence of a visual spatial code and the development of remapping across changes in limb position. J Exp Psychol. 2008; 137: 149.

- Baud-Bovy G, Tatti F, Borghese NA. Ability of low-cost force-feedback device to influence postural stability. IEEE transactions on haptics. 2014; 8: 130-139.

- Cappagli G, Finocchietti S, Baud-Bovy G, Badino L, D’Ausilio A, Cocchi E, et al. Assessing social competence in visually impaired people and proposing an interventional program in visually impaired children. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive and Developmental Systems. 2018; 10: 929-935.

- Finocchietti S, Cappagli G, Gori M. Encoding audio motion: spatial impairment in early blind individuals. Front Psychol. 2015; 6 :1357.

- Tinelli F, Gori M, Beani E, Sgandurra G, Martolini C, Maselli M, et al. Feasibility of audio-motor training with the multisensory device ABBI: Implementation in a child with hemiplegia and hemianopia. Neuropsychologia. 2022; 174: 108319.

- Maier M, Ballester BR, Verschure PF. Principles of neurorehabilitation after stroke based on motor learning and brain plasticity mechanisms. Front Ssystems Neurosci. 2019; 13: 74.

- Baroncelli L, Braschi C, Spolidoro M, Begenisic T, Sale A, Maffei L. Nurturing brain plasticity: impact of environmental enrichment. Cell Death Differentiation. 2010;17: 1092-1103.

- Neel ML, Yoder P, Matusz PJ, Murray MM, Miller A, Burkhardt S, et al. Randomized controlled trial protocol to improve multisensory neural processing, language and motor outcomes in preterm infants. BMC Pediatrics. 2019; 19: 81.

- Tierney AL, Nelson III CA. Brain development and the role of experience in the early years. Zero to three. 2009; 30: 9.

- Babik I. From hemispheric asymmetry through sensorimotor experiences to cognitive outcomes in children with cerebral palsy. Symmetry. 2022; 14: 345.

- Maitre NL, Lambert WE, Aschner JL, Key AP. Cortical speech sound differentiation in the neonatal intensive care unit predicts cognitive and language development in the first 2 years of life. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013; 55: 834-839.

- Van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH. Neural consequences of enviromental enrichment. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2000; 1: 191-198.

- Purpura G, Cioni G, Tinelli F. Multisensory-based rehabilitation approach: translational insights from animal models to early intervention. Front Neurosci. 2017; 11: 430.

- Kolb B, Gibb R. Brain plasticity and behaviour in the developing brain. J Canadian Academy Child Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011; 20: 265.

- De Giorgio A. The roles of motor activity and environmental enrichment in intellectual disability. Somatosensory Motor Res. 2017; 34: 34-43.

- Morelli F, Aprile G, Cappagli G, Luparia A, Decortes F, Gori M, et al. A multidimensional, multisensory and comprehensive rehabilitation intervention to improve spatial functioning in the visually impaired child: a community case study. Front Neurosci. 2020; 14: 768.

- Bernard-Espina J, Beraneck M, Maier MA, Tagliabue M. Multisensory integration in stroke patients: a theoretical approach to reinterpret upper-limb proprioceptive deficits and visual compensation. Front Neurosci. 2021; 15: 646698.

- Tinga AM, Visser-Meily JMA, van der Smagt MJ, Van der Stigchel S, van Ee R, Nijboer TCW. Multisensory stimulation to improve low- and higher-level sensory deficits after stroke: a systematic review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2016; 26: 73-91.

- Johansson BB. Multisensory stimulation in stroke rehabilitation. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2012; 6: 60.

- Jiang H, Stein BE, McHaffie JG. Multisensory training reverses midbrain lesion-induced changes and ameliorates haemianopia. Nature Commun. 2015; 6: 7263.

- Novak I, Morgan C, Fahey M, Finch-Edmondson M, Galea C, Hines A, et al. State of the evidence traffic lights 2019: systematic review of interventions for preventing and treating children with cerebral palsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2020; 20: 3.

- Schinhan M, Neubauer B, Pieber K, Gruber M, Kainberger F, CastellucciC, et al. Climbing has a positive impact on low back pain: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Clin J Sport Med. 2016; 26: 199-205.

- Steimer J, Weissert R. Effects of sport climbing on multiple sclerosis. Front Physiol. 2017; 8: 1021.

- Fleissner H, Sternat D, Seiwald S, Kapp G, Kauder B, Rauter R, et al. Therapeutic climbing improves independence, mobility and balance in geriatric patients. Euro J Ger. 2010; 12: 12-16.

- Buechter RB, Fechtelpeter D. Climbing for preventing and treating health problems: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. GMS German Med Sci. 2011; 9: 19.

- Böhm H, Rammelmayr MK, Döderlein L. Effects of climbing therapy on gait function in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy–A randomized, controlled crossover trial. Eur J Physiotherap. 2015; 17: 1-8.

- Koch HGB, de Oliveira Peixoto G, Labronici RHDD, de Oliveira Vargas NC, Alfieri FM, Portes LA. Therapeutic climbing: a possibility of intervention for children with cerebral palsy. Acta Fisiátrica. 2015; 22: 30-3.

- Schram Christensen M, Jensen T, Voigt CB, Nielsen JB, Lorentzen J. To be active through indoor-climbing: an exploratory feasibility study in a group of children with cerebral palsy and typically developing children. BMC Neurol. 2017; 1: 112.

- Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, Wood E, Galuppi B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Develop Med Child Neurol. 1997; 39: 214-223.

- Engel-Yeger B, Jarus T, Anaby D, Law M. Differences in patterns of participation between youths with cerebral palsy and typically developing peers. Am J Occupational Therap. 2009; 63: 96-104.

- Bourdin C, Teasdale N, Nougier V. High postural constraints affect the organization of reaching and grasping movements. Experimental Brain Res. 1998; 122: 253-259.

- Cordier P, France MM, Bolon P, Pailhous J. Entropy, degrees of freedom, and free climbing: A thermodynamic study of a complex behavior based on trajectory analysis. Int J Sport Psychol. 1993.

- Bourdin C, Teasdale N, Nougier V. Attentional demands and the organization of reaching movements in rock climbing. Res Quarterly Exercise and Sport. 1998; 69: 406-410.

- Lane SJ, Mailloux Z, Schoen S, Bundy A, May-Benson TA, Parham LD, et al. Neural foundations of ayres sensory integration®. Brain sciences. 2019; 9: 153.

- ElKholi SM, Alsakhawi RS. Improvement of Praxis Skills in Children with Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy by Using New Trend of Augmented Visual and Auditory Feedback Training: A Case Report. Open J Therap Rehabilitation. 2018; 6: 43-55.

- Kong D, Chen Y, Wang L, Lu Y, Luo S, Chai H, et al. Adoption of Rehabilitation Climbing Wall Combined with Brain-computer Fusion Interface in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 2025; 31: 208-215.

- Däggelmann J, Prokop A, Lösse V, Maas V, Otten S, Bloch W. Indoor Wall Climbing with Childhood Cancer Survivors: An Exploratory Study on Feasibility and Benefits. Klinische Pädiatrie. 2020;232: 159- 165.

- Lee H-S, Song C-S. Effects of therapeutic climbing activities wearing a weighted vest on a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a case study. J Phys Therap Sci. 2015; 27: 3337-3339.

- Mazzoni ER, Purves PL, Southward J, Rhodes RE, Temple VA. Effect of indoor wall climbing on self-efficacy and self-perceptions of childrenwith special needs. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 2009; 26: 259-273.

- Therme P, Soulayrol R. Apprentissages moteurs et psychopathologie. Pratique de l’escalade chez l’enfant psychotique. La Psychiatrie de l’enfant. 1992; 35: 519.

- Zhou H, Hu H. Human motion tracking for rehabilitation—A survey. Biomedical signal processing and control. 2008; 3: 1-18.

- Muro-De-La-Herran A, Garcia-Zapirain B, Mendez-Zorrilla A. Gait analysis methods: An overview of wearable and non-wearable systems, highlighting clinical applications. Sensors. 2014;14: 3362- 3394.

- Roy SH, Cheng MS, Chang S-S, Moore J, De Luca G, Nawab SH, et al. A combined sEMG and accelerometer system for monitoring functional activity in stroke. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering. 2009; 17: 585-594.

- Wang F, Zhang D, Hu S, Zhu B, Han F, Zhao X, editors. Brunnstrom stage automatic evaluation for stroke patients by using multi-channel sEMG. 2020 42nd annual international conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society. 2020.

- Lambelet C, Lyu M, Woolley D, Gassert R, Wenderoth N, editors. The eWrist—A wearable wrist exoskeleton with sEMG-based force control for stroke rehabilitation. 2017 international conference on rehabilitation robotics. 2017.

- Goffredo M, Infarinato F, Pournajaf S, Romano P, Ottaviani M, Pellicciari L, et al. Barriers to sEMG assessment during overground robot-assisted gait training in subacute stroke patients. Front Neurol. 2020; 11: 564067.

- Ahmad N, Ghazilla RAR, Khairi NM, Kasi V. Reviews on various inertial measurement unit (IMU) sensor applications. Int J Signal Processing Systems. 2013; 1: 256-262.

- Wang Q, Markopoulos P, Yu B, Chen W, Timmermans A. Interactive wearable systems for upper body rehabilitation: a systematic review. J Neuroeng Rehab. 2017; 14: 20.

- Felius RA, Geerars M, Bruijn SM, van Dieën JH, Wouda NC, PuntM. Reliability of IMU-based gait assessment in clinical stroke rehabilitation. Sensors. 2022; 22: 908.

- Sethi A, Ting J, Allen M, Clark W, Weber D. Advances in motion and electromyography based wearable technology for upper extremity function rehabilitation: A review. J Hand Therap. 2020; 33: 180-187.

- Boukhennoufa I, Zhai X, Utti V, Jackson J, McDonald-Maier KD. Wearable sensors and machine learning in post-stroke rehabilitation assessment: A systematic review. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control. 2022; 71: 103197.

- Chang WH, Kim Y-H. Robot-assisted therapy in stroke rehabilitation. J Stroke. 2013; 15: 174.

- Weber LM, Stein J. The use of robots in stroke rehabilitation: A narrative review. NeuroRehab. 2018; 43: 99-110.

- Loureiro RC, Harwin WS, Nagai K, Johnson M. Advances in upper limb stroke rehabilitation: a technology push. Medical & biological engineering & computing. 2011; 49: 1103-1118.

- Mousavi Hondori H, Khademi M. A review on technical and clinical impact of microsoft kinect on physical therapy and rehabilitation. J Medical Eng. 2014; 2014: 846514.

- Fathy AE, Kilic O, Ren L, Tran N, Dai TV, Foroughian F, et al. editors. Continuous Long Term Patient Motion Monitoring Using Ultra Wide Band Radar. 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation & USNC/URSI National Radio Science Meeting; 2018.

- Qi Y, Soh CB, Gunawan E, Low K-S, Maskooki A. A novel approach to joint flexion/extension angles measurement based on wearable UWB radios. IEEE J Biomed Health Informatics. 2013; 18: 300-308.

- Chen Y, Abel KT, Janecek JT, Chen Y, Zheng K, Cramer SC. Home-based technologies for stroke rehabilitation: A systematic review. Int J Med Informatics. 2019; 123: 11-22.

- Ravi DK, Kumar N, Singhi P. Effectiveness of virtual reality rehabilitation for children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: an updated evidence-based systematic review. Physiotherap. 2017; 103: 245-258.

- Phan HL, Le TH, Lim JM, Hwang CH, Koo K-i. Effectiveness of augmented reality in stroke rehabilitation: a meta-analysis. Appl Sci. 2022; 12: 1848.

- Liu Y, Qian G, editors. Projector-Camera guided fast environment restoration of a biofeedback system for rehabilitation. 2007.

- Rolland JP, Hua H. Head-mounted display systems. Encyclopedia of Optical Engineering. 2005; 2: 1-14.

- Biocca F, Levy MR. Communication in the age of virtual reality: Routledge; 2013.

- Chang E, Kim HT, Yoo B. Virtual reality sickness: a review of causes and measurements. Int J Human–Computer Interaction. 2020; 36: 1658-1682.

- Palacios-Navarro G, Hogan N. Head-mounted display-based therapies for adults post-stroke: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Sensors. 2021; 21: 1111.

- Spors S, Wierstorf H, Raake A, Melchior F, Frank M, Zotter F. Spatial sound with loudspeakers and its perception: A review of the current state. Proceedings of the IEEE. 2013; 101: 1920-1938.

- Algazi VR, Duda RO. Headphone-based spatial sound. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine. 2010; 28: 33-42.

- Arafsha F, Zhang L, Dong H, El Saddik A, editors. Contactless haptic feedback: State of the art. 2015 IEEE International Symposium on Haptic, Audio and Visual Environments and Games (HAVE); 2015: IEEE.

- Stein BE, Stanford TR, Rowland BA. The neural basis of multisensory integration in the midbrain: its organization and maturation. Hearing Res. 2009; 258: 4-15.

- Zmigrod S, Hommel B. Feature integration across multimodal perception and action: a review. Multisensory Res. 2013; 26: 143-57.

- Slater M, Linakis V, Usoh M, Kooper R, editors. Immersion, presence and performance in virtual environments: An experiment with tri- dimensional chess. Proceedings of the ACM symposium on virtual reality software and technology; 1996.

- Sigrist R, Rauter G, Riener R, Wolf P. Augmented visual, auditory, haptic, and multimodal feedback in motor learning: a review. Psychonomic Bull Rev. 2013; 20: 21-53.

- Pohl P, Carlsson G, Bunketorp Käll L, Nilsson M, BlomstrandC. Experiences from a multimodal rhythm and music-based rehabilitation program in late phase of stroke recovery–A qualitative study. PloS one. 2018; 13: e0204215.

- Ouchi H, Nishida Y, Kim I, Motomura Y, Mizoguchi H, editors. Detecting and modeling play behavior using sensor-embedded rock-climbing equipment. Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children; 2010.

- Vähämäki J. Real-time climbing pose estimation using a depth sensor. 2016.

- Liljedahl M, Lindberg S, Berg J, editors. Digiwall: an interactive climbing wall. Proceedings of the 2005 ACM SIGCHI International Conference on Advances in computer entertainment technology; 2005.

- Colombo A, Canina M, Ferrise F, Dozio N, Fedeli F, Brondolin R, et al., editors. Accept–a sensorized climbing wall for motor rehabilitation. Book of the 5th International Rock Climbing Research Congress; 2021.

- Szabó Z. Intuitive Interaction on a Climbing Wall—Designing Short Circuit. 2025.

- Martin-Niedecken AL, Rogers K, Turmo Vidal L, Mekler ED, Márquez Segura E, editors. Exercube vs. personal trainer: evaluating a holistic, immersive, and adaptive fitness game setup. Proceedings of the 2019 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems; 2019.

- Setti W, Engel IA-M, Cuturi LF, Gori M, Picinali L. The Audio-Corsi: an acoustic virtual reality-based technological solution for evaluating audio-spatial memory abilities. Journal on Multimodal User Interfaces. 2022; 16: 207-218.

- Attig C, Rauh N, Franke T, Krems JF, editors. System latency guidelines then and now–is zero latency really considered necessary? International Conference on Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics; 2017.

Abstract

Post-stroke plasticity has received much attention from neuroscientists and has been deeply studied in adult populations. Despite this progress, plasticity mechanisms and implications for rehabilitation in children likely differ from later ages and are generally lacking. We therefore propose a non-exhaustive review of pediatric stroke rehabilitation, also related to multisensory processing. We focus both on the traditional rehabilitation approach and a more innovative process, with a specific focus on climbing, an activity chosen for its intrinsically multisensory features. We also have also deepened the use of multimodal technologies, to improve engagement and participation in children with variable disability. At the end of the review, we present guidelines to create more usable technologies that produce quantifiable benefits. That can serve as a common framework for structuring and facilitating interdisciplinary research in the field. As the review clearly shows, the use of multisensory skills, also based on intelligent technology, combined with physical activities, can improve engagement in pediatric rehabilitation for children with pediatric stroke.

Keywords

• Pediatric Stroke

• Climbing Therapy

• Multisensory Feedback

• Rehabilitation technologies

Citation

Gori M & Basta S, Cornaglia S, Crepaldi M, Parmiggiani A, et al. (2025) Multisensory Full-Body Training for Stroke Children: The Case of Climbing. J Neurol Disord Stroke 12(3): 1244.

ABBREVIATIONS

AIS: Adolescents with Idiopathic Scoliosis; BCI: Brain Computer Interface; CIMT: Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy; CP: Cerebral Palsy; CT: Climbing Therapy; EMG: Electromyography; HABIT: Hand–Arm Bimanual Intensive Therapy; HABIT-ILE: HABIT-Including Lower Extremity; ICF: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; IMUs: Inertial Measurement Units; LEDs: Light Emitting Diodes; ML: Machine Learning; MSI: Multisensory Integration; ToF: Time of Flight; VR: Virtual Reality.