Right Hemisphere Dysfunction is Better Predicted by Emotional Prosody Impairments as Compared to Neglect

- 1. Departments of Neurology Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

- 2. Department of Epidemiology, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University; Baltimore, MD, USA

- 3. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

- 4. Department of Cognitive Science, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA

Abstract

Background: Neurologists generally consider hemispatial neglect to be the primary cognitive deficit following right hemisphere lesions. However, the right hemisphere has a critical role in many cognitive, communication and social functions; for example, in processing emotional prosody (tone of voice). We tested the hypothesis that impaired recognition of emotional prosody is a more accurate indicator of right hemisphere dysfunction than is neglect.

Methods: We tested 28 right hemisphere stroke (RHS) patients and 24 hospitalized age and education matched controls with MRI, prosody testing and a hemispatial neglect battery. Emotion categorization tasks assessed recognition of emotions from prosodic cues. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were used to compare tests in their ability to distinguish stroke patients from controls.

Results: ROC analyses revealed that the Prosody Score was more effective than the Neglect Battery Score in distinguishing stroke patients from controls, as measured by area under the curve (AUC) ; Prosody Score = 0.84; Neglect Battery Score =0.57. The Prosody Score correctly classified 78.9%, while Neglect Score correctly classified 55.8% of participants as patients versus controls. The Prosody Score was similar to the total NIH Stroke Scale in identifying RHS patients (AUC=0.86, correctly classifying 80.1% of patients versus controls), but the tests only partially overlapped in the patients identified.

Conclusions: Severe prosody impairment may be a better indicator of right hemisphere dysfunction than neglect. Larger studies are needed to determine if including a bedside test of Prosody with the NIH Stroke Scale would most efficiently and reliably identify right hemisphere ischemia.

Keywords

• Prosody

• Neglect

• Emotions

• Stroke

• Right hemisphere

• Communication

Citation

Dara C, Bang J, Gottesman RF, Hillis AE (2014) Right Hemisphere Dysfunction is Better Predicted by Emotional Prosody Impairments as Compared to Neglect. J Neurol Transl Neurosci 2(1): 1037

ABBREVIATIONS

ADC: Apparent Diffusion Coefficient; AUC: Area Under the Curve; DWI: Diffusion Weighted Imaging; FLAIR: fluid attenuation inversion recovery; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; RHS: right hemisphere stroke; ROC: Receiver Operating Curve; USN: Unilateral spatial neglect

INTRODUCTION

It is generally believed that the most common cognitive deficits following right hemisphere stroke are unilateral spatial neglect (USN) and extinction with double simultaneous stimulation [1]. USN is typically defined as an inability to detect, attend or respond to stimuli on the side of space contralateral to brain damage, while detecting and responding to stimuli on the ipsilesional side [2]. Approximately 25-30% of acute right hemisphere stroke patients have USN [3]. The only “right hemisphere” cognitive deficits evaluated by the NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) are neglect and extinction [4]. One limitation of this fact is that the NIHSS may be less sensitive to right hemisphere than left hemisphere stroke, or may underestimate the volume of right hemisphere stroke [4].

However, the right hemisphere has other cognitive functions that are less widely recognized that may be at least equally important from a functional standpoint and may provide clinical markers that are more reliable than USN for indicating the presence or severity of right hemisphere stroke (RHS). Adding evaluation of such cognitive functions could improve detection and evaluation of outcome of RHS. For example, the right hemisphere is critical for emotional prosody (expression or comprehension of emotional meaning through speech prosody, such as variations in pitch, intensity, and rate). Individuals with right hemisphere lesions have shown difficulty identifying emotions (such as happy, angry, sad, and fearful) of the speaker during human communication. The predominant role of the right hemisphere in processing emotional prosody is corroborated by studies recording event-related brain potentials [5]; fMRI studies showing right hemisphere activation in association with prosody judgments [6,7]; a left ear advantage for prosody using the dichotic listening paradigm [8,9]; and lesion studies of judging emotional meaning from prosody [10-14]. There are a number of other “right hemisphere deficits” that have clear functional consequences, such as anosognosia and apathy (see, 15, 16), integration of information to comprehend discourse, interpret metaphor, draw inferences, and so on (see, 17) for review). It is also crucial for both affective empathy (the ability to recognize and respond to affective experiences of another person; (18, 19) and cognitive empathy (the ability to take the perspective of another person). However, impairments in many of these cognitive functions are difficult to objectively quantify on a scale of more than a few points. One reason USN may have been used so frequently as the primary marker of right hemisphere cognitive function is that it is relatively easy to measure the severity with a variety of bedside pencil and paper, computer, or other standardized tests. We hypothesized that impairment in comprehension of emotional prosody, which can also be measured on a scale of 0-100% accuracy on objective and reliable tests, is even more sensitive and specific for RHS than is USN.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

A series of 28 patients with acute RHS (mean age 55 years old and mean education 14 years) and 24 patients with transient ischemic attacks (TIA) admitted to Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, USA were recruited for this study. TIA participants were included as age and education matched controls without evidence of brain lesion on MRI and resolution of presenting symptoms at the time of testing, but with similar socioeconomic background as the stroke patients and same testing environment as the stroke patients. All patients were examined on the clinical and behavioral tests within 48 hours from the admission to the hospital. Exclusion criteria included: bilateral brain damage, injury to brainstem/cerebellum, history of other major neurological or psychiatric illness or previous stroke, and positive toxicology screens for drugs of abuse or alcohol.

Imaging: Lesion location for all patients was identified by the neuroradiologist and technicians on MRI sequences, which included: Axial diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) trace sequences and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps, fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) to evaluate for old strokes, susceptibility weighted images to evaluate for hemorrhage, and T2 weighted sequences to evaluate for other lesions. Technicians masked to behavioral assessment measured volume of infarct on DWI.

EXPERIMENTAL TASKS

Emotional prosody tasks

Two categorization tasks evaluated emotional processing for prosodic features alone. In the word identification task (word ID), participants were presented utterances that were semantically neutral but communicated specific emotions through the prosody (e. g. , I am going to the other movies). In the monosyllabic identification task (monosyllabic ID), participants were presented with monosyllabic utterances that conveyed specific emotions through prosody (e. g. , ba ba ba ba ba ba ba). In word and monosyllabic ID tasks, participants listened to each utterance (from an audio file) and then identified the emotion of the speaker based on the prosodic features in a six forced-choice response format (alternatives - happy, surprise, angry, sad, disinterest, neutral) presented as a picture and as a word on a laptop or on paper. Stimuli for each of these tasks were specifically developed to assess comprehension of emotional prosody in patients as well as healthy adults and this type of stimuli has been used successfully in previous studies [14,20]. The administration time for these two tasks ranged from 5.4 to 7.6 minutes.

Neglect tasks

Hemispatial neglect tests administered as part of the Stroke Cognitive Outcomes and REcovery (SCORE) study included: [1] copy scene (copying the “Ogden scene”: a house, a fence, and two trees; there are 36 total components to the picture, so each missing component yields a percent error) ; [2] a gap detection test (identifying the gaps in small and large circles (21). In this test, a sheet of paper filled with 10 whole circles, 10 circles with gaps on the left, and 10 circles with gaps on the right was presented to the patient. Patients were instructed to cross out the circles with the gaps and to circle the full circles on the paper. This test was administered at midline of the patient’s body. For each task, the number of errors and the total number of stimuli were tabulated. Errors on each side of the page and/or stimulus were recorded in order to distinguish between viewer- and stimulus-centered neglect. The test is administered twice, once with large circles, and once with smaller circles. The administration time for these tasks ranged from 2.9 to 5.8 minutes. Error rate on the SCORE neglect tests potentially ranged from 0-100%.

Neglect and extinction as scored on the NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) were also recorded for each patient. The NIHSS scores were obtained by reading through the admission history and physical notes, progress notes from the first full day of admission, and discharge summaries. If NIHSS was not documented, a retrospective NIHSS was calculated using the algorithm used by Williams et al. , 2000 [22]. Neglect is assessed on the basis of describing a complex picture, reading words and sentences, and eye movements (pursuits). Extinction is assessed with double simultaneous stimulation in tactile and visual modalities. Each participant was scored as having neglect [0-1], extinction [0-1] or both (maximum of 2 possible points).

Procedure

Ethical approval of the study was obtained from the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board, and informed written consent was obtained from all participants prior to testing. Participants were tested in their individual rooms in the Stroke ward. Testing was carried out in one session; these tests were part of a larger battery that included assessment of prosody production and imitation, as well as other cognitive assessments. Auditory stimuli were presented by a laptop over headphones controlled by Presentation software (NeuroBehavioral Systems, USA). Stimuli within each task were randomized and then played over high quality, volume adjustable headphones at a comfortable listening level. They were instructed to listen carefully to each utterance and then make a judgment about the emotion of the speaker. Most patients responded by pressing a button on a Cedrus 730 response box. For these patients, the response alternatives (verbal labels) were presented centrally on the computer screen as well as marked on the response box. However, for the initial 18 patients, response alternatives were presented on paper, and the patient simply pointed to the emotion of the speaker. There was no time limitation for the participants and the next trial was presented only after the participant had provided a response. There was not a marked difference in the administration time for the two subtests when the paper version was used versus the computer version.

Statistical analyses

Firstly, to examine the performance of the two participant groups (RHS, TIA), two 2 x 2 ANOVAs were conducted separately for prosody identification and neglect tasks. Secondly, Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analyses were conducted to identify a more accurate cut-off point that could help identify the probability of disease in individual participants [23]. ROC curves were created by plotting the range of sensitivity and specificity pairs for each participant’s error rate, with case status (stroke versus TIA) as the classifier variable. A global assessment of the performance of the test is given by the area under the ROC curve (AUC). That is, AUC provides an estimate of the accuracy of the diagnostic test in discriminating between the patients and controls. AUC’s were compared for different tests in their characteristics relative to case status. In addition to the AUC, when evaluating the usefulness of a screening measure to identify those individuals with cognitive impairment, the cut-off point would be chosen to ensure that most cases were detected (high sensitivity; >80% is desirable) but not at the cost of many false positives (goal specificity; >60% is acceptable; 24). Therefore, cut-offs were selected that maximized the sensitivity (>80%) of the tests while maintaining an acceptably low false positive rate (specificity > 60%).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Results

A 2 x 2 ANOVA with factors of Group (RHS, TIA) and Prosody (word ID, monosyllabic ID) revealed a significant main effect of Group, F [1,50] = 29.22, p < 0.00001 and a main effect of Prosody, F [1,50] = 8.51, p < 0.01. Post-hoc Tukey’s (HSD) inspection of the group effect revealed that the RHS patients (M=0.49% errors) made significantly more errors than the TIA group (M=0.25% errors). Also, the prosody main effect showed that both the groups tend to make more errors in the prosody word ID task (M=0.43% errors) as compared to the monosyllabic ID task (M=0.33% errors). A 2 x 2 ANOVA with factors of Group (RHS, TIA) and SCORE Neglect (viewer-centered, stimulus-centered) did not reveal any main or significant effects. The neglect scores from the NIHSS were also similar. Out of 28 patients, 3 patients showed signs of neglect, 5 patients showed signs of extinction, and 2 patients had both neglect and extinction. All individuals with neglect on either test also had impaired prosody. A summary of the mean error rate for the prosody and SCORE neglect tasks is shown in the table 1.

Table 1: Demographics and mean error rates on the prosody and neglect tasks for RHS and control participants.

|

Participants |

Age |

Education |

Sex |

Prosody ID |

Neglect |

||

|

word |

monosyllabic |

Viewer Centered |

Stimulus Centered |

||||

|

RHS (n=28) |

55.93 |

13.62 |

12 female |

0.54 |

0.43 |

0.01 |

0.02 |

|

SD |

11.69 |

2.94 |

|

0.19 |

0.22 |

0.06 |

0.07 |

|

Controls(n=24) |

51.71 |

13.33 |

16 female |

0.30 |

0.21 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|

SD |

10.11 |

3.95 |

|

0.22 |

0.12 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Abbreviations: SD: standard deviation

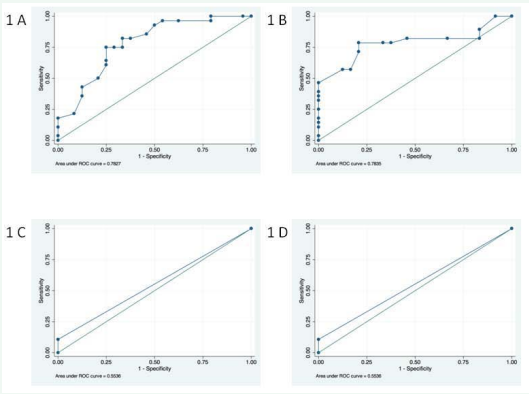

The ROC analysis showed that the Prosody Score was more effective than the SCORE Neglect Score in distinguishing stroke patients from controls, as measured by the ROC curve (AUC for the overall Prosody Score = 0.84; AUC for the overall Neglect Score = 0.57). The overall Prosody score of >31% error correctly classified 78.9% of the participants versus controls. For the overall Prosody score, the sensitivity was 92.9% and the specificity was 62.5%. For the prosody word ID task, an error rate of > 37% had a sensitivity of 82.1% and specificity of 66.7% (correctly classifying 75% of participants as patients versus controls). An error rate of > 33% on the prosody monosyllabic ID task had a sensitivity of 78.6% and specificity of 79.2% (correctly classifying 78.9% of participants as patients versus controls) ; ROC curves are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 ROC curve plots for the prosody and neglect tasks. Panel A) This graph shows the ROC curve for the error rates for prosody word ID task with an area under the ROC curve = 0.78. Panel B) This graph shows the ROC curve for the error rates for prosody monosyllabic ID task with an area under the ROC curve = 0.78. Panel C) This graph shows the ROC curve for the stimulus-centered neglect measure with an area under the ROC curve = 0.55. Panel D) This graph shows the ROC curve for the viewer-centered neglect measure with an area under the ROC curve = 0.55.

In contrast, the AUC for SCORE neglect summary score was 0.55 for both viewer-centered and stimulus-centered neglect measures. At most, the SCORE Neglect Score could classify 55.8% of patients vs. controls. Of 28 RHS patients, only 5 (17.9%) patients made fewer errors than the cut-off point on the prosody word ID task and 6 (21.4%) patients made fewer errors than the cut-off point on the prosody monosyllabic ID task; whereas 24 (85.7%) patients made 0% errors on the SCORE Neglect tests. The possible range of cut-off points for the sensitivity and specificity for prosody scores on the two ID tasks and neglect measures are shown in Figure 1.

The AUC for NIHSS Neglect was 0.63 and for Extinction was 0.57, and for both was 0.66. Again, prosody was significantly better than NIHSS neglect/extinction in distinguishing stroke patients from controls in this study. Using quintile scores for Prosody Recognition (so that they would have similar scales, rather than comparing a 100 point continuous scale to a 3 point scale), the AUC for Prosody was significantly higher than the NIHSS neglect/extinction score of 0-2 (χ2 = 4.0; p= 0.047).

The SCORE neglect tests identified three stroke patients with neglect who were not identified by the NIHSS as having neglect, but two were identified as having extinction on the NIHSS. The NIHSS identified 7 participants as having extinction, but one was a control.

The AUC for the total NIHSS score was 0.86; it classified 80.8% of patients. Three patients were detected with prosody who were not detected with NIHSS; both had cortical strokes (two parietal, one frontal). Two patients were detected with NIHSS who were not detected with the prosody summary score; one had a subcortical infarct and one had an in infarct in the motor strip. Therefore, the most effective classification of right hemisphere stroke patients versus controls was with the NIHSS score combined with the Prosody Score, yielding an AUC of 0.89 (CI 0.81-0.98). Together, they classified 82.7% of patients. Table 2

Table 2: Comparison of sensitivity and specificity of SCORE Neglect, NIHSS, and Prosody tests.

|

Test |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

% Correctly classified |

|

SCORE Neglect Test |

14.30% |

100.00% |

55.80% |

|

NIHSS Extinction |

17.90% |

95.80% |

53.90% |

|

NIHSS Neglect+Extinction |

35.70% |

95.80% |

63.50% |

|

Total NIHSS Score |

75.00% |

87.50% |

80.80% |

|

Prosody |

92.90% |

62.50% |

78.90% |

Abbreviations: SCORE: Stroke Cognitive Outcome and Recovery; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

summarizes the sensitivity and specificity of each test.

Discussion

The current study investigated whether deficits in emotional prosody comprehension are more sensitive than neglect for identifying acute stroke in the right hemisphere. The ROC analysis shows that RHS patients have a higher probability of showing significant impairment in processing emotional prosody than showing significant neglect or extinction. The overall Prosody Score could classify 78.9% of patients vs. controls. In contrast, the SCORE Neglect tests could classify only 55.8% of patients vs. controls, and NIHSS neglect/extinction could classify 63.5 of patients vs controls. The SCORE neglect tests detected three additional stroke patients beyond those detected by NIHSS neglect test, but two of those three were also detected by the NIHSS extinction test. NIHSS extinction identified 7 participants with extinction, but one of these was a control. Still, NIHSS neglect plus extinction was slightly better in detecting right hemisphere stroke than the SCORE neglect tests alone (without extinction). Nevertheless, testing prosody detected 15 more patients with right hemisphere stroke than the NIHSS neglect plus extinction. The two prosody subtests took minimally more time (5.4-7.6 minutes) compared to neglect subtests (2.9-5.8 minutes) and slightly more equipment. Although we presented the audiofiles on a laptop, they could as easily be presented from a smart phone, i-pod, or other electronic storage device. We have also presented the response alternatives on either paper or laptop. The neglect tests were “paper and pencil” tests, but laptop versions could be created, particularly for the gap detection test.

Cancellere and Kertsez, 1990 proposed that impairments in recognition of emotions from prosodic cues in patients with right hemisphere lesions may be due to attentional difficulties [12]. The current study does not provide clear support for this hypothesis. In spite of spared performance on neglect tasks, many RHS patients were profoundly impaired on the prosody tasks. Our study indicates that neglect (one type of spatial attention) and emotional prosody impairment are independent deficits caused by a stroke in the right hemisphere. There is other evidence that RHS patients have significant difficulty in comprehension of emotions from prosody without visual neglect [13]. However, such findings do not rule out that other types of attentional deficits may underlie both prosodic impairments and neglect.

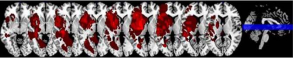

Some brain regions have been identified that can result in both emotional prosody comprehension impairment and neglect. Using multivariate pattern analysis of activation during a gender recognition task during event-related functional MRI of young healthy adults, Ethofer and colleagues [2009] observed that each emotion category had a different localization of activation. However, all emotion categories activated voxels in bilateral mid superior temporal gyrus (STG; (25), implicating the role of mid STG in processing prosodic features irrespective of the emotion category. Right STG has been associated with left USN [1,26-28] or at least left stimulus-centered neglect [29]. Several studies have implicated the right inferior frontal gyrus in evaluative judgments of emotional prosody [30,31] and inferior frontal lobe in neglect tasks [32,33]. Patients in our study as well had lesions in frontal, temporal and parietal regions. An overlay of lesions of all the patients is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Lesions overlay of the RHS patients. An overlay of the lesions of the 28 patients with the right hemisphere stroke (RHS). Nine slices are presented with all strokes from all the patients overlaid.

One account of the rare neglect in RHS patients in this study is that we might not have used adequately sensitive tests of USN. However, the NIHSS also demonstrated that only 18% patients had neglect. Additionally, we have previously used these tests along with more traditional tests such as line bisection, line cancellation, reading, clock drawing, and have found that these two tests identified virtually all patients with neglect [34].

An alternative account of the rare neglect in RHS patients in our study is the relatively small lesions (0.2 cc to 98.8 cc range; mean = 53.79 cm3 ). Severity of extinction and neglect correlates with the volume of infarct [35] and volume of hypoperfusion [36] in acute stroke. Moreover, the patients were relatively young compared to some previous studies (range= 33-75; mean=55.25 years), although the age was average age of stroke patients for our hospital. Previous studies have shown that neglect is more common and more severe after right hemisphere stroke in older individuals [37,38]. Therefore, spared performance of many of our RHS patients on neglect tasks suggests that either [1] the spatial attention network is intact in the majority of our patients, or [2] hemispatial neglect requires “two hits”: damage to one component of the spatial attention work, and damage to a more general attentional system for vigilance. This latter hypothesis is consistent with the model of Corbetta and Schulman [39], which accounts for neglect in large right MCA strokes as damage to both the bilateral dorsal spatial attention network and the right-dominant, nonspatial ventral attention network. It may be that comprehension of emotional prosody is a better marker of right hemisphere stroke than neglect in unselected, diverse stroke patients (many of whom have small strokes, and now have average age of 55), while neglect remains a strong marker of large right MCA stroke. The important point is that neglect is not the only cortical function that is impaired after RHS. The addition of test of other right hemisphere cortical functions, such as prosody, would improve detection of RHS.

CONCLUSION

The important finding of our study is that impairments in comprehension of emotional prosody is a common indicator of acute right hemisphere dysfunction – even more common than hemispatial neglect or extinction in some populations. These results indicate that acute stroke assessment could be improved by including a test (perhaps a downloadable audio file for a mobile phone) of prosodic comprehension. Furthermore, the addition of evaluation of prosody comprehension may improve our measures of effectiveness of interventions to salvage right cortical function, such as reperfusion therapies. However, the effectiveness, reliability, and efficiency of testing prosody comprehension at bedside (e. g. in an Emergency Department setting, which might require headphones) would need to be tested in a much larger study with an independent population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, RO1NS47691 (to AEH)