The Association between Maternal Depression, Infant Characteristics and Need for Assistance in A Low-IncomeCountry

- 1. Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Science, South Africa

- 2. Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine and Health Science, South Africa

- 3. Department of Statistics and Actuarial Science, Faculty of Economic and Management Science, South Africa

- 4. Robert’s Program on Sudden Unexpected Death in Pediatrics, Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, USA

Abstract

Background: Depression in the peripartum period is prevalent in low-income-countries. The identification of women needing referral is often lacking and on the other hand, women in need of support and treatment do not make use of existing support.

Objectives: To identify risk factors for fetal and postnatal consequences of depression in pregnancy and to investigate further management once women at risk have been identified.

Methods: The Safe Passage Study was a large prospective multicenter international study. Extensive information, including the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS), was collected during the study. At risk women were referred to the study’s social worker (SW). Women were categorized according to risk on their EPDS results. Risk categories were characterized and investigated for infant outcomes.

Results: Data from 5,489 women were available for analysis and revealed a 51% prevalence of prenatal depression. Fourteen percent of at-risk women attended SW appointments, while 36% accepted the SW referral but persistently failed to attend. At risk women were significantly younger, had less formal education, had lower monthly income, and lived in more crowded conditions. They used significantly more alcohol and cigarettes. Their infants had shorter gestational ages, lower birth weights and were more growth restricted. Infants of depressed women who missed appointments weighed less and were moregrowth restricted.

Conclusion: Women with high EPDSs had less favorable socioeconomic conditions, used more alcohol or tobacco during pregnancy, and their infants weighed less with more growth restriction. Women who repeatedly missed their appointments came from the poorest socioeconomic conditions and their infants had worse birth outcomes.

Keywords

Depression, Pregnancy, Small-for-gestational age, BMI, Mid upper arm circumference, Acceptance for referral, Birthweight , One-year follow-up, Smoking and drinking

Citation

Odendaal HJ , Human M, van der Merwe C, Brink LT, Nel DG, et al. (2021) The Association between Maternal Depression, Infant Characteristics and Need for Assistance in A Low-Income-Country. J Subst Abuse Alcohol 8(2): 1090.

ABBREVIATIONS

EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; SPS: Safe Passage Study; LMIC: Low-and-middle-income countries; SGA: Small-for-gestational age; IUGR: Intrauterine growth restriction; PASS: Prenatal Alcohol and SIDS and Stillbirth; CHC: Community Health Clinic; LBW: Low Birth Weight; SW: Social worker; GA: Gestational age; CRF: Case Report Form; MUAC: Mid upper arm circumference; BMI: Body mass index

INTRODUCTION

Depression is a common and serious illness worldwide, and a priority of the WHO’s mental health Gap Action Program (mhGAP). Depression is prevalent during pregnancy. In highincome countries, 1 in 10 women develop perinatal depression whereas the rate in developing countries is 1 in 5.(1) In a systematic review involving more than 19,000 pregnancies in 21 selected studies, rates of depression in the first, second and third trimesters of pregnancy were 7.4%, 12.8%, and 12.0%, respectively. (2) Researchers report higher rates in sub-Saharan Africa countries: 22.7% in Swaziland, (3) 27% in Soweto, Johannesburg, (4) and 39% in two peri-urban areas in Cape Town, (5) with even higher rates (47%) found in rural areas in South Africa. (6) Depression has detrimental effects on maternal and child health, where depressed pregnant mothers participate in unhealthy behaviors such as poor self-care and nutrition, and increased use of tobacco and substances. There is also an increased risk of post-partum depression when depression is present prenatally, which may lead to mother-child attachment difficulties and impaired infant care practices. (7)

The Edinburg postnatal depression scale (EPDS) is a 10 question self-report screening tool for pre- and postnatal depression. Although no screening tool is diagnostic, it has been shown to have a sensitivity of 86%, specificity of 78% and a positive predictive value 73% using threshold criteria of greater than 13. Its reliability and validity have been confirmed in 9 different North and sub-Saharan African countries, (9) including validation as a screening instrument in a South African urban community. (10) Previous research has documented an association of high EPDS in pregnant mothers with small-forgestational age (SGA), (11) low birthweight,(12,13) intrauterine growth restricted (IUGR), (14) and preterm infants. (15)

The multicentered prospective Safe Passage Study (SPS), conducted by the NIH-sponsored Prenatal Alcohol and SIDS and Stillbirth (PASS) Network, collected extensive maternal, fetal and infant data in order to investigate the association of drinking and smoking during pregnancy with stillbirths and sudden infant deaths(16). In addition to exposure data on alcohol and smoking, demographic and clinical data were collected, including the EPDS. Prospective data on fetal growth and physiology, and infant outcomes were also collected. This research used the rich data from the SPS to examine associations between depression during pregnancy and neonatal and infant outcomes in a specific, well-characterized population, hypothesizing that depression is an independent risk factor for neonatal and infant outcomes. We further hypothesized that surveillance and referral for depression would improve those outcomes. We analysed SPS data to investigate the association of a high EPDS with IUGR and poor growth at the age of one year.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recruitment of SPS participants occurred at a Community Health Centre (CHC) in a defined residential area close to Tygerberg Hospital in the northern suburbs of Cape Town from August 2007 to January 2015. Eligibility criteria included: a pregnancy with one or two fetuses not currently in active labour, with an estimated gestational age (GA) of at least 6 weeks; the ability to provide informed consent; maternal age of 16 years or older; and the ability to speak English or Afrikaans. A woman was excluded if a planned abortion was considered, she relocated from the catchment area prior to delivery, or if participation was advised against by a health care provider. Informed consent was obtained at the initial recruitment visit.

Determination of GA was done by ultrasound at the first or before the second antenatal visit by a trained midwife or experienced ultrasonographer. Trained research midwives used structured case report forms (CRFs) to collect demographic, socioeconomic and further data at recruitment or at subsequent follow-up antenatal visits. The EPDS and other CRFs were administered at the first follow-up visit (20-24, 28-32, or 34+ week’s gestation). Alcohol use and cigarette smoking details were collected at up to 4 occasions during pregnancy using the revised timeline follow back method.(17)

All anthropological measurements of the mother and infant were performed twice. If measurements differed by more than 1 kg or 2 mm for mother or 0.2 kg or 2 mm for infant, a third measurement was done. The mean of the two closest measurements was then calculated by the system to avoid the influence of outliers. Reference values from the Intergrowth-21 study were used to determine whether the newborns weighed below the 10th percentile. (18)

According to SPS protocol, participants with a EPDS of higher than 13 or participants who endorsed the item indicating thoughts of self-harm, regardless of EPDS, were referred to the study social worker for further management. Participants failing to attend the appointment were contacted again and encouraged to reschedule. To simplify consultations, the social worker also visited the CHC for several hours every week to be readily available, should the women find it difficult to attend an appointment at Tygerberg Hospital. After the initial consultation with the social worker, the importance of follow-up visits was explained, and further appointments were scheduled. Where indicated, referrals were made to specialized services such as psychiatry, different governmental and non-governmental institutions, or support groups based upon the acuity of presenting concerns.

After completion of the study, participants were categorized into a group with an EPDS of 13 or less and no indication of selfharm; and a group with an EPDS higher than 13 and/or thoughts of self-harm. The latter group was further subcategorized into three groups: participants declining referral to the social worker straightaway (Declined); participants accepting the referral and seen by SW (Seen); and participants accepting the referral to the SW but repeatedly missing appointments despite numerous attempts to reschedule (Missed).

Hypothesis tests for equality of means of different groups were done with analysis of variance (ANOVA). Bonferroni or least significant difference multiple comparison procedures identified significant differences among the means in the ANOVA. If the Levene test indicated non-homogeneous variances among the groups, a Welch ANOVA test was done with a Games-Howell multiple comparison among the means. If some covariates seem to influence the outcome of the ANOVA, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was done with the same nominal variables as in the ANOVA corrected for the covariate(s). The Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test compared differences between two or more groups when responses are not normally distributed. The maximum likelihood Chi-square test determined significance in categorical data. Pearson or Spearman correlations measured correlations between several continuous or ordinal response variables. A p-value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant and 95% confidence intervals used to describe the estimation of unknown parameters.

Permission or the study was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee of Stellenbosch University (N06/10/210), and the Western Cape Department of Health. The study was conducted in accordance with the South African Good Clinical Guidelines (DOH 2006) and the Declaration of Helsinki (2013).

RESULTS

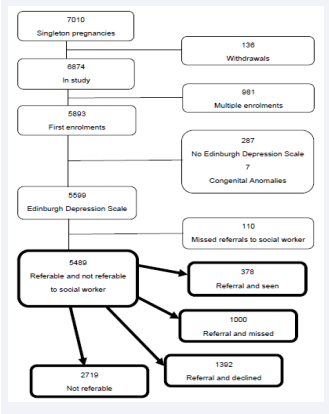

A total of 7,010 women with singleton pregnancies were recruited at two antenatal clinics in Cape Town. Complete data from otherwise uncomplicated live births were available from 5,489 women for analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Study profile.

The prevalence of prenatal depression, as measured by EPDS of higher than 13 or the endorsement of an item indicating thoughts of self-harm, regardless of EPDS, was 50.5% (n=2,770). Fifty percent of the group immediately declined a referral (n=1392) (mean EPDS 16.6±3.2), while 14 % of the women (n= 379) (mean EPDS 19.1±4.3) accepted the referral and were seen by the SW at least once. Thirty-six percent of the group with significant EPDS results and referred for support (n=1000) (mean EPDS 18.6±3.7) initially agreed to attend a session with the SW, but never honored the appointment despite numerous attempts to make contact.

Firstly, the not-referable group (EPDS of 13 or less) was compared with the referable group. Secondly, the three referable subgroups (group declined, group seen, and group missed) were analysed for the effect of depressive symptoms on infant birthweight z-scores and infant biometry at one year with demographic, socioeconomic and exposure data as confounders. Further analysis was conducted to determine whether referral was associated with improved growth parameters.

Maternal characteristics

Comparing not-referable women to referable women, the latter were younger and had lower weights, with lower mid upper arm circumferences (MUAC) and BMIs (Table 1). Referable women also had fewer years of education, lived in more crowded conditions, had lower incomes (Table 2), used more alcohol and tobacco, and had more alcoholic binges while pregnant (Table 3).

Comparing the three high EPDS sub-groups, those who declined referral straightaway had a significantly lower EPDSs. They were younger, of lower gravidity, weighed less, and had lower MUAC’s (Table1). They completed more years of education, had higher incomes, and lived in less crowded conditions (Table 2). They smoked significantly less (Table 3). Among the groups accepting referral, those in the Seen category were poorer and less educated. No significant differences were found in their age, BMI, or alcohol and tobacco use.

Birth Outcomes

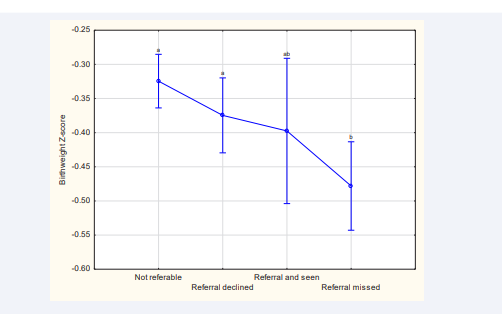

When comparing non-referable women to referable women, the latter significantly delivered earlier, and their infants had lower birthweights and were more growth restricted. When comparing the three groups with high EPDSs, those who declined referral straightaway had heavier and less growth restricted babies (Table 4). The lowest birthweight z-score was observed in the missed appointment group (Table 4, Figure 2).

Figure 2: Birthweight z-scores for different reference groups Significant differences between birthweight z-score and different reference groups were found (F (3, 1540)=5.3839; p<0.01). Whiskers denote 95% bootstrap confidence intervals, and duplicated letters above whiskers indicate absence of a significant difference.

One-year infant outcomes

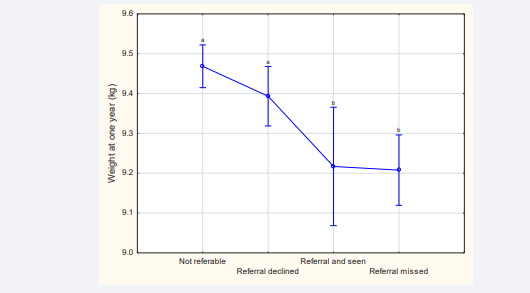

When comparing the infants from non-referable women to those from referable women, the latter had significantly lighter and shorter infants at the one year follow up. When comparing the infants from three groups with high EPDSs, infants of women who declined referral straightaway had significantly heavier and taller infants at the one year follow up (Table 5). The lowest weight was observed in the missed appointment group (Table 5, Figure 3).

Figure 3: Infant weight at one year for different reference groups Significant differences between age at one year for the different reference groups were found (F (3, 1 4963)=9.9128; p<0.01). Whiskers denote 95% bootstrap confidence intervals, and duplicated letters above whiskers indicate absence of a significant difference.

The effects of the maternal covariates: age, BMI, education, income, smoking and drinking on infant outcomes are presented in (Table 6). None of the covariates caused the p-value of the ANOVA to change from significant to insignificant with respect to the EPDS when the covariate is introduced in the ANCOVA. Therefore, the dependence of the response variable on the nominal variable EPDS did not change significantly when corrected for the covariates

DISCUSSION

Programs for women and children in developing countries typically focus on the improvement of nutrition and physical health, but pay less attention to the emotional and mental wellbeing of the women and its consequent effects on their infants (19).We found that depression was a prevalent finding in our SPS cohort of pregnant women, as over half (50.5%) of the participants reported EPDS higher than 13, thus meeting criteria for referral to provide assessment and support. We found that a high EPDS is an independent risk factor for detrimental infant outcomes. Our finding is higher than the 38.5% prevalence antenatal depression in KwaZulu-Natal as reported by Manikkam, (20) but comparable to the occurrence of 47,4% seen in postpartum women in Eswatini (21) and by Rochat (47%) in a cohort of perinatal women in Cape Town. (6) Our observed rates were in accord with the previously reported prevalence of depression in urban areas of South-Africa.

The birthweights of infants born to higher EPDS mothers were significantly lower than those in the non-referable group. The significance of this result stands in contrast to the varying associations between depression and birthweight that have been reported in the literature, including the lack of association, (22) increased birthweights (23) and a modest effect as reported in a systematic review of research predominantly conducted in high income countries. (24) Beyond statistical significance, low-income-countries face the additional challenges of limited awareness and appreciation of mental disorders and the extent of the issue may be under-reported and under-treated. The time pressures in primary care, insufficient access to specialists and the paucity of culturally validated screening tools also impact research in prenatal mental health in low-income countries. (25)

Our study further revealed that infant z-scores of birthweights for gestational age and gender in the referable group were significantly lower than those of the non-referable group. It has been found that pregnant women with depression developed poor dietary intake and had increased incidence of fetal growth restriction, but not of LBW. (26) Other reports also confirm the association with fetal growth restriction, (27) or reported inconsistent findings. (29-30) The association of depression with gestational age at delivery varies. Some reports found no association between depression and preterm birth, (31-32) while others found an independent association between depression and shorter gestation or premature delivery. (26, 30, 33)

Despite the associated effects we observed, half of women who endorsed depressive symptoms on the EPDS immediately refused a referral to a social worker for further attention and assistance, while another 36% accepted a referral but never attended the appointment, despite repeated attempts to see them. Only 14 % of qualifying women attended an appointment with the SW, with the implication that 86% (2392) women with substantial depressive symptoms remained without support in a system designed to optimize the likelihood of their attendance.

Women had EDPS scores higher than 13 were younger, had lower BMI’s and educational levels, worse socio-economic conditions, and used more alcohol and tobacco. They lived in more crowded homes and had lower incomes. Compounding the effect of poverty on mental illness it is estimated that only 20-25% of this population had access to adequate treatment, barriers the SPS attempted to remove. There are, of course, other numerous barriers to treatment. (34) Anecdotally, major barriers were the fear of losing one’s baby if depressive feelings were disclosed, and fear of not coping. Further barriers included shame, stigma and being perceived as weak, and a burden to their families.

When declining referral was compared with accepting referral yet failing to attend, the latter group was associated with higher EPDS, older age, more children, a larger MUAC, lower education and income, more cigarette smoking and living in more crowded conditions. These mothers’ infants had lower birth weights and birthweight z-scores, with general stunting at one-year follow-up, as evident with lower weight and height of infant. This is consistent with research by Wallwiener where infants of women diagnosed with depression during pregnancy were delivered preterm and/or had underweight babies. (35) Depressive symptoms during pregnancy were associated with an increased LBW even after adjusting potential confounders. (12)

The group who did not honor their appointments was at highest risk group for detrimental infant outcomes, evident by their infants having the lowest overall weight at one-year follow-up. Reasons for the failure to attend the appointments were not documented, but previous research provided different barriers to the uptake of mental health support. Mental disorders often result in a lower uptake of available services by pregnant women. Kopelman et al., (36) found that women with high EDPS scores, reported financial constraints, lack of medical insurance and transportation, long queues for treatment, previous bad experience with mental health and not knowing where to go as barriers to accept treatment. They also reported the women expressed distrust and concern for jeopardizing their parental rights if they acknowledge their need for assistance. Kim et al., report availability of time to be the some relevant barrier to service, with reference to stigma of seeing a mental health professional, lack of therapeutic knowledge and aversion to therapy as further possible reasons for refusal. (37) In this study most women were apprehensive their life-partners would learn they were seeing someone for help and possibly criticizing them. The mothers were also concerned of statutory intervention by the SW, and that they will be seen as weak and denied that anything was wrong, and they were not stressed.

Little information could be found on the association of depression and infant biometry at one year. However, there seems to be an association between head circumference at birth and subsequent measurements until the age of two years. (38)

None of the covariates caused the p-value of the ANOVA to change from significant to insignificant with respect to the EPDS when the covariate was introduced in the ANCOVA. Thus, the dependence of the response variable on the nominal variable EPDS did not change significantly when corrected for the covariates (Table 6).

Our study has some limitations, as it did not address the associations of depression with food insecurity and interpersonal violence. Abrahams et al. (39) reported a strong association between food security and depression in pregnant women and Barnett et al. (40) found that antenatal maternal depression is associated with interpersonal violence, childhood trauma and food insecurity. The EPDS was only completed once during the pregnancy and therefor the course and progression of changes in mood was not determined.

| Edinburgh postnatal depression scale | Outcome of referral | ||||||

| Variable | Not Referable N=2 719 | Referable N= 2 770 | P M-W U | Declined N=1 392 | Seen N=378 | Missed N=1 000 | P K-W |

| Age (years) | 25.0; 6.1 24; 16-45 | 24.1; 5.8 23; 16-43 | <0.01 | 23.5; 5.7 22b ; 16-43 | 24.8; 5.9 24a ; 16-42 | 24.8; 5.8 24a ; 16-43 | <0.01 between a and b |

| Gravidity | 2.1; 1.2 2; 1-8 | 2.1; 1.3 2; 1-10 | 0.79 | 2.0; 1.3 2b ; 1-10 | 2.3; 1.3 2a ; 1-7 | 2.3; 1.4 2a ; 1-8 | <0.01 between a and b |

| Weight (kg) | 65.4; 15.3 62.4; 30.1-132 | 63.4; 14.7 60.2;34-136 | <0.01 | 63.1; 14.4 59.9b ; 34-134 | 64.9; 15.9 60.7a ; 40.6-128 | 63.3; 14.6 60.5; 37.5-136 | <0.01 between a and b |

| MUAC (mm) | 278.6; 46.4 270.0; 175-480 | 272.8; 44.6 264.5; 186-535 | <0.01 | 271.7; 44.1 263.5b ; 186-535 | 278.1; 48.5 270a ; 196-455 | 272.2; 43.8 263.5b ; 187-475 | <0.01 between a and b |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.9; 5.8 24.6; 13.7-52.3 | 25.2; 5.6 23.9; 14.8-55.9 | <0.01 | 25.1; 5.6 23.8; 15.3-55.9 | 25.7; 5.9 24.2; 16.9-47.3 | 25.1; 5.4 23.8; 14.8-47.4 | No significant differences |

| GA (days) Enrolment | 139.3; 47.4 138; 42-247 | 140.8; 48.6 149; 38-276 | 0.23 | 140.4; 47.4 139; 42-276 | 142.3; 49.5 141.5; 50-258 | 140.7; 50.5 142; 138-271 | No significant differences |

| First line of variable: mean; standard deviation Second line of variable: median; minimum-maximum Abbreviations: MUAC= Mid upper arm circumference; BMI= Body mass index, M-W U= Mann-Whitney U test, K-W= Kruskal-Wallace test | |||||||

| Edinburg postnatal depression scale | Outcome of referral | ||||||

| Variable | Not Referable N=2 719 | Referable N=2 770 | P M-W U | Declined N=1 392 | Seen N=378 | Missed N=1 000 | P K-W |

| EPDS | 8.0; 3.4 9; 0-13 | 17.6; 3.7 17; 2-30 | <0.01 | 16,6; 3.2 16.0b ; 2-30 | 19.1; 4.3 19a ; 6-30 | 18.6; 3.7 18.0a ; 3-30 | <0.01 between a and b |

| Education (years) | 10.3; 1.7 10; 2-13 | 9.8; 1.7 10; 3-13 | <0.01 | 10.0; 1.7 10.; 4-13 | 9.5; 1.8 10; 4-13 | 9.7; 1.7 10; 3-13 | <0.01 between all columns |

| People/ Room | 1.5; 0.9 1.25; 0.25-16 | 1.6; 1.0 1.4; 0.25-11 | <0.01 | 1.6; 0.8 1.4b ; 0.3-7 | 1.8; 1.2 1.5a ; 0.3-11 | 1.7; 1.0 1.4a ; 0.25-8 | <0.01 between a and b |

| Income ZAR/month | 949; 612 833; 50-6 000 | 792; 578 667; 45-5 000 | <0.01 | 880; 623 750; 45-5 000 | 620; 495 500; 45-3 000 | 749; 527 667; 50-4 000 | <0.01 between all columns |

| First line of variable: mean; standard deviation Second line of variable: median; minimum-maximum Abbreviations: EPDS=Edinburgh postnatal depression scale, ZAR=South African Rand, M-W U=Mann-Whitney U test, K-W=Kruskal-Wallace test | |||||||

| Edinburgh postnatal depression scale | Outcome of referral | ||||||

| Variable | Not Referable N=2 719 | Referable N=2 770 | M-W U | Declined N=1 392 | Seen N=378 | Missed N=1 000 | P K-W |

| Total drinks in pregnancy | 10.8; 29.7 2.0; 0-817 | 15.3; 36.0 3.5; 0-564 | <0.01 | 14.1, 34.6 3.17; 0-540 | 16.7; 33.4 4.7; 0-299 | 16.6; 38.7 3.7; 0-564 | No significant differences |

| Total binges in pregnancy | 1.0; 2.9 0; 0-44 | 1.5; 3.8 0; 0-50 | <0.01 | 1.4; 3.7 0; 0-50 | 1.7; 3.9 0; 0-35 | 1.7; 3.9 0; 0-36 | No significant differences |

| Cigarettes per day | 2.5; 3.3 1.0; 0-22.5 | 3.2;3.9 2.2; 0-53.0 | <0.01 | 2.9; 3.6 1.7a ; 0-20.0 | 3.3; 4.6 2.3; 0-53. | 0 3.6; 4.0 2.7b ; 0-35.0 | <0.01 between a and b |

|

First line of variable: mean; standard deviation Second line of variable: median; minimum-maximum Abbreviations: M-W U=Mann-Whitney U test, K-W=Kruskal-Wallace test |

|||||||

| Edinburgh postnatal depression scale | Outcome of referral | ||||||

| Variable | Not Referable N=2 691 | Referable N=2 730 | P M-W U | Declined N=1 377 | Seen N=366 | Missed N=987 | P K-W |

| GA (days) Delivery | 373.1; 15.8 275; 157-313 | 272.2; 16.0 275; 156-307 | <0.01 | 272.6; 16.2 275; 159-305 | 272.5; 16.0 275; 156-307 | 271.5; 15.9 274; 164-304 | No significant differences |

| Birthweight (g) | 3 035; 583 3 060; 190-5 140 | 2 980; 578 3 000; 360-5 740 | <0.01 | 3 005; 578 3 030a ; 410-5 740 | 2 995; 549 3 000; 635-4 890 | 2 939; 587 2 960b ; 360-4 540 | <0.01 between a and b |

| Birthweight z-score | -0.33; 1.05 -0.34; -6.34-3.61 | -0.42; 1.02 -0.44; -5.37-4.12 | <0.01 | -0.38; 1.00 -0.42a ; -3.72-4.12 | -0.40; 1.04 -0.38; -3.31- 2.79 | -0.48; 1.04 -0.49b ; -5.37- 3.12 | <0.01 between a and b |

| One minute Apgar score | 8.7; 1.0 9; 0-10 | 8.7; 1.0 9; 0-10 | 0.53 | 8.7; 1.1 9; 0-10 | 8.8; 0.9 9; 1-10 | 8.7; 1.0 9; 1-10 | No significant differences |

| Five minute Apgar score | 9.8; 0.6 10; 1-10 | 9.7; 0.8 10; 0-10 | 0.57 | 9.7; 0.8 10; 1-10 | 9.8; 0.7 10; 1-10 | 9.8; 0.7 10; 0-10 | No significant differences |

|

First line of variable: mean; standard deviation Second line of variable: median; minimum-maximum Abbreviations: GA=gestational age, M-W U=Mann-Whitney U test, K-W=Kruskal-Wallace test |

|||||||

| Edinburgh postnatal depression scale | Outcome of referral | ||||||

| Variable | Not Referable N=2 478 | Referred N=2 516 | P M-W U | Declined N=1 279 | Seen N=322 | Missed N=915 | P K-W |

| Age (days) | 371.6; 16.0 369; 330-488 | 371.4; 16.8 369; 330-475 | 0.93 | 371; 16 369; 330-470 | 371; 18 368.5; 330-475 | 372; 17 369; 330-475 | No significant differences |

| Weight (Kg) | 9.5; 1.4 9.35; 9.35; 5.6-15.3 | 9.3;1.3 9.2; 5.6-16.9 | <0.01 | 9.4; 1.3 9.3a ; 5.6-16.9 | 9.2; 1.3 9.15b ; 6.1- 14.6 | 9.2; 1.3 9.2b ; 6.0- 14.4 | <0.01 between a and b |

| Height (cm) | 73.8; 3.0 73.8; 60.8 – 85.0 | 73.5;3.0 73.5; 60.7-88.0 | <0.01 | 73.7; 3.0 73.7a ; 64.3-88.0 | 73.0; 3.1 73.1b ; 60.7 – 83.2 | 73.3; 2.9 73.4b ; 61.1-82.0 | <0.01 between a and b |

| HC (cm) | 46.1; 1.5 46.0; 41.6-51.0 | 46.0; 1.5 46; 40.3-54.7 | 0.09 | 46.1; 1.5 46a ; 40.3- 54.7 | 45.9; 1.5 46b ; 41.2- 51.2 | 46.0; 1.5 46.0; 41.1- 51.0 | <0.01 between a and b |

|

First line of variable: mean; standard deviation. Second line of variable: median; minimum-maximum Abbreviations: HC= head circumference, M-W U= Mann-Whitney U test, K-W= Kruskal-Wallace test |

|||||||

| Response variable | ANOVA | ANCOVA | ANCOVA | ANCOVA | ANCOVA | ANCOVA | ANCOVA | |||||||

| Covariate | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P |

| Age | BMI | Education | Income | Drink | Smoke | |||||||||

| BW-Z | 5.4 | <0.001 | 5.3 | <0.01 | 3.7 | <0.05 | 3.8 | <0.01 | 4.1 | <0.01 | 4.1 | <0.01 | 4.2 | <0.01 |

| OYW | 9.9 | <0.0001 | 10.1 | <0.0001 | 8.7 | <0.0001 | 4.84 | <0.01 | 5.2 | <0.01 | 8.4 | <0.0001 | 7.7 | <0.0001 |

| OYL | 12 | <0.0001 | 12.1 | <0.0001 | 11.9 | <0.0001 | 6.12 | <0.001 | 7.8 | <0.0001 | 11.0 | <0.0001 | 10 | <0.0001 |

|

None of the covariates caused the p-value of the ANOVA to change from significant to insignificantly with respect to the EPDS when the covariate is introduced in the ANCOVA. Thus, the dependence of the response variable on the nominal variable EPDS did not change significantly when corrected for the covariates. Abbreviations: BW-Z= birthweight z-score, OYW= weight at one year, OYL=length at one year, BMI=body mass index |

||||||||||||||

CONCLUSION

Our research demonstrates the association between poor socioeconomic conditions, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption with depression in pregnancy. Routine screening for depression as part of antenatal care is recommended with follow up for fetal growth, in particular in women with poor compliance. Our research further identifies the challenges of intervening on mothers living in the circumstances in which this research was conducted.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The study was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders: U01 HD055154, U01 HD045935, U01 HD055155, U01 HD04599 and U01 AA016501.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organisation. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. 2004.

2. Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, Koren G, Einarson TR. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 103: 698-709.

3. Målqvist M, Clarke K, Matsebula T, Bergman M, Tomlinson M. Screening for Antepartum Depression Through Community Health Outreach in Swaziland. J Community Health. 2016; 41: 946-952.

4. Redinger S, Norris SA, Pearson RM, Richter L, Rochat T. First trimesterantenatal depression and anxiety: prevalence and associated factorsin an urban population in Soweto, South Africa. J Dev Orig Health Dis.2018; 9: 30-40.

5. Hartley M, Tomlinson M, Greco E, Comulada WS, Stewart J, et al. Depressed mood in pregnancy: prevalence and correlates in two Cape Town peri-urban settlements. Reprod Health. 2011. 2; 8: 9.

6. Rochat TJ, Tomlinson M, Bärnighausen T, Newell ML, Stein A. The prevalence and clinical presentation of antenatal depression in rural South Africa. J Affect Disord. 2011; 135: 362-373.

7. Stewart DE. Depression during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2012; 67: 141-143.

8. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of Postnatal Depression:Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987 ;150: 782-786.

9. Tsai AC, Scott JA, Hung KJ, Zhu JQ, Matthews LT, et al. Reliability and Validity of Instruments for Assessing Perinatal Depression in African Settings: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2013; 8: e82521.

10.Lawrie TA, Hofmeyr GJ, de Jager M, Berk M. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale on a cohort of South African women. S Afr Med J. 1998; 88: 1340-1344.

11.Babu GR, Murthy GVS, Reddy Y, Deepa R, Yamuna A, et al. Small for gestational age babies and depressive symptoms of mothers during pregnancy: Results from a birth cohort in India. Welcome Open Res. 2020. 6; 3: 76.

12.Li X, Gao R, Dai X, Lui H, Zhang J, Lui X, et al. The association between symptoms of depression during pregnancy and low birth weight: a prospective study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020; 20: 147.

13.Tomlinson M, O’Connor MJ, le Roux IM, Stewart J, Mbewu N, et al. Multiple risk factors during pregnancy in South Africa: the need for a horizontal approach to perinatal care. Prev Sci. 2014 ; 15: 277-282.

14.Tsakiridis I, Dagklis T, Zerva C, Mamopoulos A, Athanasiadis A, et al. Depression in pregnant women hospitalized due to intrauterine growth restriction: Prevalence and associated factors. Midwifery. 2019; 70: 71-75.

15.Mochache K, Mathai M, Gachuno O, Vander Stoep A, Kumar M. Depression during pregnancy and preterm delivery: a prospective cohort study among women attending antenatal clinic at Pumwani Maternity Hospital. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2018; 17: 31.

16.Dukes KA, Burd L, Elliott AJ, Fifer WP, Folkerth RD, et al. The safe passage study: design, methods, recruitment, and follow-up approach. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2014; 28: 455-465.

17.Dukes K, Tripp T, Petersen J, Robinson F, Odendaal H, et al.PASS Network. A modified Timeline Follow back assessment to capture alcohol exposure in pregnant women: Application in the Safe Passage Study. Alcohol. 2017; 62: 17-27.

18.Villar J, Giuliani F, Bhutta ZA, Bertino E, Ohuma EO, et al. International Fetal and Newborn Growth Consortium for the 21(st) Century (INTERGROWTH-21(st)). Postnatal growth standards for preterm infants: the Preterm Postnatal Follow-up Study of the INTERGROWTH21(st) Project. Lancet Glob Health. 2015; 3: e681-691.

19.Sheeba B, Nath A, Metgud CS, Krishna M, Venkatesh S, et al. Prenatal Depression and Its Associated Risk Factors Among Pregnant Women in Bangalore: A Hospital Based Prevalence Study. Front Public Health. 2019. 3; 7: 108.

20.Manikkam L, Burns JK. Antenatal depression and its risk factors: An urban prevalence study in KwaZulu-Natal. S A Med J. 2012; 102: 940- 944.

21.Dlamini LP, Mahanya S, Dlamini SD, Shongwe, M. Prevalence and factors associated with postpartum depression at a primary healthcare facility in Eswatini. S Afr J Psychiatr. 2019; 25: 1-7.

22.Broekman BF, Chan YH, Chong YS, Kwek K, Cohen SS, et al. The influence of anxiety and depressive symptoms during pregnancy on birth size. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2014; 28: 116-126.

23.Ecklund-Flores L, Myers MM, Monk C, Perez A, Odendaal HJ, et al. Maternal depression during pregnancy is associated with increased birth weight in term infants. Dev Psychobiol. 2017; 59: 314-323.

24.Grigoriadis S, Vonder Porten EH, Mamisashvili L, Tomlinson G, Dennis CL, et al. The impact of maternal depression during pregnancy on perinatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013; 74: 321-341.

25.Gelaye B, Rondon MB, Araya R, Williams MA. Epidemiology of maternal depression, risk factors, and child outcomes in low-incomeand middle-income countries. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016; 3: 973- 982.

26.Saeed A, Raana T, Saeed AM, Humayun A. Effect of antenatal depression on maternal dietary intake and neonatal outcome: A prospective cohort. Nutr J 2016;15: 1-9.

27.Bansil P, Kuklina EV, Meikle SF, Posner SF, Kourtis AP, et al. Maternal and fetal outcomes among women with depression. J Womens Health(Larchmt). 2010; 19: 329-334.

28.Maina G, Saracco P, Giolito MR, Danelon D, Bogetto F, et al. Impact of maternal psychological distress on fetal weight, prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation. J Affect Disord. 2008; 111: 214-220.

29.Lewis AJ, Austin E, Galbally M. Prenatal maternal mental health and fetal growth restriction: A systematic review. J Dev Orig Health Dis.2016; 7: 416-428.

30.Diego MA, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C, et al. Prenatal depression restricts fetal growth. Early Hum Dev. 2009; 85: 65-70.

31.Brittain K, Myer L, Koen N, Koopowitz S, Donald KA, et al. Risk factorsfor antenatal depression and associations with infant birth outcomes: Results from a south african birth cohort study. Paediatr PerinatEpidemiol. 2015; 29: 504-514.

32.Stewart RC, Ashorn P, Umar E, Dewey KG, Ashorn U, et al. The impact of maternal diet fortification with lipid-based nutrient supplements on postpartum depression in rural Malawi: a randomised-controlled trial. Matern Child Nutr. 2017; 13: 1-14.

33.Gudmundsson P, Andersson S, Gustafson D, Waern M, Östling S, et al. Depression in Swedish women: Relationship to factors at birth. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011; 26: 55-60.

34.Dennis CL, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: A qualitative systematic review.Birth. 2006; 33: 323-331.

35.Wallwiener S, Goetz M, Lanfer A, Gillessen A, Suling M, et al. Epidemiology of mental disorders during pregnancy and link to birth outcome: a large-scale retrospective observational database study including 38,000 pregnancies. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019; 299: 755-763.

36.Kopelman RC, Moel J, Mertens C, Stuart S, Arndt S, O’Hara MW, et al. Barriers to care for antenatal Depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2008; 59: 429-432.

37.Kim JJ, La Porte LM, Corcoran M, Magasi S, Batza J, et al. Barriers to mental health treatment among obstetric patients at risk for depression. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 312: e1-5

38.Sindhu KN, Ramamurthy P, Ramanujam K, Henry A, Bandu JD, et al. Low head circumference during early childhood and its predictors in a semi-urban settlement of Vellore, Southern India. BMC Pediatr. 2019; 19: 1-11.

39.Abrahams Z, Lund C, Field S, Honikman S. Factors associated with household food insecurity and depression in pregnant South African women from a low socio-economic setting: a cross-sectional study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018; 53: 363-372.

40.Barnett W, Pellowski J, Kuo C, Koen N, Donald KA, et al. Food-insecure pregnant women in South Africa: A cross-sectional exploration of maternal depression as a mediator of violence and trauma risk factors. BMJ Open. 2019; 9:1-11.