Analysis of Diagnosis and Treatment of 19 Cases of Neck Trauma with Larynx and Trachea Injury

- 1. Department of Otorhinolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery, Fuyang People’s Hospital Fuyang, China

- 2. Department of Otorhinolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery, Fuyang Hospital Affiliated with Bengbu Medical University (Fuyang People’s Hospital), Fuyang, 236000, China.

- 3. Department of Clinical Science, Intervention and Technology, Karolinska Institute, Sweden

- 4. Ear, Nose and Throat Patient Area, Trauma and Reconstructive Medicine, Karolinska University Hospital, Sweden

Abstract

Objective: This study aimed to explore the clinical features and treatment strategies for neck trauma involving laryngeal and tracheal injuries.

Methods: We retrospectively evaluated 19 patients with neck trauma associated with laryngeal and tracheal injuries who were admitted to our hospital between July 2016 and August 2024. Following stabilization of vital signs, laryngeal and tracheal reconstruction surgeries were performed based on the location and severity of the injury, followed by postoperative rehabilitation. Postoperative assessments were conducted to evaluate the restoration of respiration, voice, swallowing, and other functions.

Results: After a 3–6 months follow-up, 17 of the 19 patients exhibited significant improvement in their respiratory, vocal, and swallowing functions. One patient exhibited poor voice recovery due to recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, which subsequently improved through a second surgery and rehabilitation, while another patient developed pharyngeal leakage postoperatively due to infection; however, the patient recovered after changing the dressing.

Conclusion: Prompt, effective, and personalized treatment of concomitant neck injuries involving laryngeal and tracheal injuries can optimize the preservation of patients' respiratory, vocal, and swallowing functions.

Keywords: Neck Trauma; Larynx Injury; Trachea Injury; Fracture; Emergency

Abbreviations: CT: computed tomography

Introduction

Advanced technology has resulted in an increased prevalence of neck injuries owing to the extensive use of machines by humans. Traffic accidents are the most common type of trauma, with a mortality rate of 2.5%, ranking 10th among global causes of death, and resulting in over 3,200 deaths per day, especially in developing countries [1]. A previous study demonstrated that laryngotracheal injuries occur at a rate of approximately one in 30,000, with an attributable mortality rate of 17.9% and an immediate mortality rate of over 75% [2]. The complex, severe, urgent, and unpredictable nature of neck injuries often involves critical structures such as the trachea, esophagus, cervical vertebrae, major blood vessels, and nerves, resulting in a high incidence of mortality and functional impairment. Poor patient outcomes are frequently associated with delayed accurate diagnosis and inadequate treatment [3,4]. Therefore, it is clinically significant to explore the clinical features and management strategies for neck injuries associated with laryngeal and tracheal injuries. This study presents 19 cases of neck injuries, including laryngeal and tracheal injuries, treated at our hospital.

Materials and Methods

General information

We analyzed 19 patients (15 males and 4 females, aged 27–65 years, mean age 41.47 years) with neck trauma associated with laryngeal and tracheal injuries treated at our hospital between July 2016 and August 2024. The etiologies of injury were as follows: 11 cases resulting from traffic accidents, 5 cases from falls, and 3 cases from puncture wounds. Of the 19 patients, 15 sustained multiple injuries throughout the body, four experienced isolated neck trauma, 18 presented with laryngeal and tracheal skin lacerations, and one exhibited occult laryngeal and tracheal injuries. On initial admission, 13 patients were admitted to the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, four to the Department of Neurosurgery, and two to the Department of Orthopedics.

Clinical features

All 19 patients had a history of trauma, 10 of whom presented with dyspnea, 14 with hemoptysis, seven with hoarseness, and two with a disorder of consciousness. Lacerations on the neck skin were observed in 18 patients, and crepitus of the neck in 16 patients. All imaging examinations revealed varying degrees of neck emphysema, and 18 patients exhibited clear fractures or joint dislocations.

Treatment methods

For patients initially admitted to our department, we performed imaging examinations of the neck to evaluate injuries, fracture locations, and respiratory conditions. Subsequently, emergency neck surgery was performed, including laryngotomy, tracheostomy, and laryngotracheal repair as indicated. The oral and maxillofacial surgery teams were consulted for associated jaw and facial fractures when necessary. One patient experienced hemorrhagic shock during surgery and underwent tracheostomy and wound closure before being transferred to the intensive care unit for blood loss correction and subsequent surgery. Two patients with mild neurological symptoms and two orthopedic patients were admitted within 24 hours and underwent surgeries in collaboration with our department following the same surgical plan as those admitted to our department. Two patients with impaired consciousness underwent temporary tracheostomy and wound closure to ensure stable respiration, with plans for second surgery within 2–3 weeks. One patient with diabetes developed postoperative infection and pharyngeal leakage; however, blood glucose was managed and long-term dressing changes were administered, leading to recovery. Of the 19 patients, 18 underwent tracheostomy, and nine underwent laryngotomy.

Efficacy evaluation

Good recovery: No dyspnea, hoarseness, dysphagia, or laryngeal or tracheal stenosis was observed on imaging.

Residual dysfunction: Dyspnea, hoarseness, dysphagia, or other functional disorders, with laryngeal and tracheal stenosis on imaging.

Typical cases

A 33-year-old male was admitted to the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery because of breathing difficulty for 4 hours following a fall. The patient's family reported that, while riding a bike home 4 hours before presentation, he accidentally fell while evading a vehicle. His condition at that time was unknown. He was transported to a local hospital via an emergency ambulance. After relevant examinations and considering the severity of his condition, he was transferred to our hospital for further assistance. He presented with breathing difficulties, hemoptysis, dysphonia, and restlessness, with an unknown amount of blood loss. Rapid fluid administration was performed during transport to maintain blood pressure. Upon admission, physical examination revealed a temperature of 36.5 ?, pulse rate of 82 beats/min, respiratory rate of 18 breaths/min, and blood pressure of 92/68 mmHg. The neck was straight, the trachea was at the midline, and subcutaneous emphysema was palpable on the neck and anterior chest. A skin laceration with an irregular shape and surrounding bloodstains was observed on the right side of the jaw, a skin laceration approximately 4 cm in length was observed on the nasal bridge, and there was significant swelling around the left orbit. Ancillary tests: Cranial computed tomography (CT) of the neck, chest, full abdomen, nasal cavity, and eyes revealed no intracranial hematoma or skull fracture; however, a fracture of the medial wall of the left orbit, associated with edema of the left eyelid soft tissue, swelling of the nasal soft tissues, and fracture of the thyroid cartilage was observed. Additionally, subcutaneous emphysema in the neck, air accumulation in the mediastinum, and traumatic changes in both lungs, consistent with the clinical findings, were observed, with no significant abnormalities in the full abdomen (Figure 1). On the same day, a temporary tracheostomy and wound hemostasis were performed as emergency interventions. During surgery, the patient's blood pressure decreased to 64/38 mmHg, after which he was transferred to the intensive care unit for anemia correction. Thyrohyoid cartilage molding was performed 10 days later. The surgical field in the neck was sterilized and draped, followed by tracheal tube insertion and anesthesia catheter fixation. The incision was extended upwards to the hyoid level, the skin was incised, and a white line was identified. The anterior cervical strap muscles were retracted to expose the thyrohyoid cartilage, cricoid cartilage, and inferior margin of the hyoid bone. During surgery, fractures and collapse of both the thyrohyoid plates were observed, with greater severity on the left side. A midline incision was made, and the outer periosteum of the thyrohyoid plate was dissected to the posterior-lateral margin of the left thyrohyoid plate. The cricothyroid membrane was incised longitudinally and the collapsed thyrohyoid plate was excised along the fracture line. Examination of the laryngeal cavity revealed granulation tissue in the left vocal cord vestibule and at the root of the epiglottis. The wound edges were trimmed, and local alignment sutures were placed to restore the optimal natural space in the laryngeal cavity and bilateral vocal cord posture. A nasogastric tube was inserted and secured. The wound was irrigated, hemostasis was achieved, a drainage tube was inserted, and the anterior cervical strap muscles and skin were sutured. The balloon-tipped plastic tracheal tube was replaced, and the neck was dressed. After six months, the patient's voice recovered, and no respiratory distress was observed after the tracheostomy tube was removed. Fiberoptic laryngoscopy revealed no significant stenosis or abnormal glottic movement (Figure 2), and CT scans revealed no significant narrowing of the larynx or trachea (Figure 3). Subsequently, tracheostomy tubes were removed. The patient was satisfied with the outcomes.

Figure 1

Figure 1: Thyroid cartilage fracture

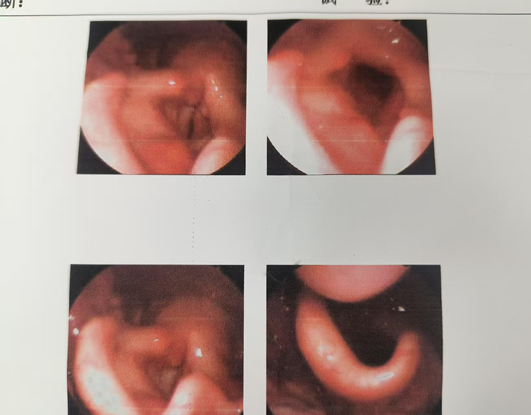

Figure 2

Figure 2: The glottis can close properly without stenosis

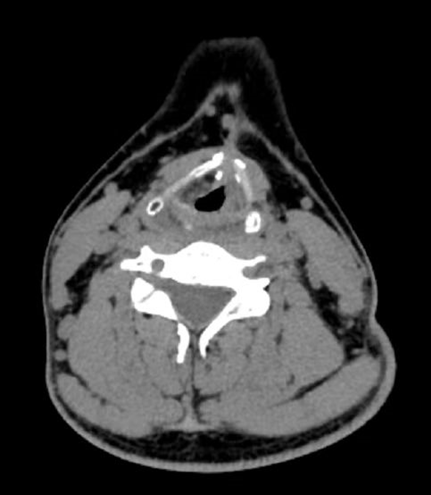

Figure 3

Figure 3: Following the repositioning of the thyroid cartilage, there is no significant narrowing observed in either the larynx or the trachea.

Results and Discussion

After follow-up visits in March and June after surgery, 17 patients exhibited satisfactory recovery of respiration, vocal, and swallowing functions without significant narrowing of the larynx or trachea observed on repeat CT scans. One patient experienced poor vocal recovery due to recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, which improved through rehabilitation and a second surgery, and another patient developed pharyngeal leakage associated with infection, which resolved after dressing changes. The neck, an essential structure connecting the body and brain through nerves and blood vessels, is usually exposed to acute, life-threatening injuries in patients with trauma, frequently endangering their lives. Specifically, penetrating neck injuries are associated with a high mortality rate (10%) [5]. Previous studies have demonstrated that approximately 85% of patients with neck and laryngeal tracheal trauma experience subcutaneous emphysema and hemoptysis, often associated with voice changes, speech difficulty, aphonia, coughing, and hoarseness [6]. Laryngeal and tracheal injuries are rare, with incidence rates ranging from 1 in 5,000 to 1 in 137,000 [7]. Because of their low incidence, even highly experienced head and neck surgeons may lack sufficient experience in managing laryngeal and tracheal injuries [8]. Inadequate management can lead to early asphyxiation, potentially resulting in death, as well as subsequent complications including airway stenosis, hoarseness, and swallowing difficulties. Patients with neck trauma associated with laryngeal and tracheal injuries frequently experience multiple injuries owing to the effects of various injury factors. Carotid artery rupture and airway obstruction were the most common causes of death. No cases of carotid artery rupture were observed in the included patients. This may be attributed to the high prehospital mortality associated with this rupture, likely due to the lack of effective hemostatic measures during transportation, which prevents patients from surviving long enough to reach the hospital. One patient experienced a ruptured internal jugular vein that was successfully treated after compression hemostasis during transportation, and subsequently underwent repair surgery. In addition to controlling bleeding, maintaining an open airway is essential during the rescue process. A previous study demonstrated that the acute mortality rate of patients with neck respiratory tract injuries was 3%, primarily due to laryngeal and tracheal injuries caused by blunt or penetrating neck injuries [9]. The cricoid cartilage is the only complete ring of cartilage in the larynx and trachea. Its fracture can cause collapse of the laryngeal cavity, resulting in airway obstruction and asphyxiation, especially in patients with transtubercular tracheal injuries, who may survive only a few minutes [10]. Among the treated patients, one presented with a transtubercular tracheal injury. The laceration provided a passage for ventilation, and bleeding from the wound was promptly controlled, allowing the patient to be successfully transferred to our hospital for treatment. The primary objective of surgery is to relieve the airway obstruction. Endotracheal intubation can be performed preoperatively in patients without significant airway narrowing or disruption. If intubation is impossible, emergency tracheostomy should be performed. If necessary, cricothyrotomy can be performed as a preparatory procedure. To modify the surgical plan, imaging and fiberoptic endoscopy can be performed in the early stages for patients without obvious rapid blood loss or respiratory distress. Nine patients were admitted in relatively stable condition, and our department opted for neck exploration, laryngotracheal repair, and laryngeal fissure investigation after completing the initial examinations. In emergency cases, once urgent bleeding and airway obstruction are resolved, further localization of the injury can be determined, and additional imaging and fiberoptic endoscopy may be performed to evaluate whether laryngeal and tracheal function reconstruction is required. Determination of the surgical plan relies on imaging and fiberoptic endoscopy. Additionally, CT scans can reveal air accumulation in the neck and detect laryngeal fractures and dislocations [11]. Diagnosis relies more on imaging studies, particularly for hidden laryngeal and tracheal injuries caused by blunt trauma. In one case, the diagnosis of concealed laryngeal and tracheal injuries depended primarily on imaging studies. Fiberoptic endoscopy can identify the location and shape of injuries within the larynx and trachea, as well as the morphology of the piriform sinus and vocal cords. If possible, performing the examination before general anesthesia can provide insight into vocal cord movements. Consequently, we assert that a comprehensive preoperative auxiliary examination is essential. For patients with neck trauma associated with laryngeal and tracheal injuries, debridement, tracheostomy, and restoration of laryngeal and tracheal function can be performed simultaneously. This approach can effectively shorten hospital stay, reduce secondary injuries, and improve patient satisfaction. Patients with arytenoid cartilage injury or dislocation are at high risk of poor functional recovery due to scar formation. Therefore, early surgical fixation and repositioning are strongly recommended to improve patient outcomes. However, in critically ill patients, overall stability should be ensured before proceeding with the second-stage surgery. In this study, 15 of 19 patients underwent first-stage surgery, while four required second-stage surgery. Two patients were admitted with impaired consciousness and one patient was admitted with hemorrhagic shock. The first-stage surgery typically involves tracheostomy and debridement, followed by transfer to the intensive care unit for correction of anemia before second-stage surgery. One patient experienced recurrent laryngeal nerve injury with persistent dysphonia; however, functional improvement was achieved through rehabilitation and second-stage surgery. Surgical treatment should be dynamically adjusted according to the location and severity of the injury. Supraglottic injuries primarily cause inspiratory dyspnea, and treatment focuses on preventing asphyxiation. Internal fixation, including Foley balloon catheter packing, can be used to maintain the preoperative conditions. Glottic injuries primarily manifest as unequal vocal cord length, soft tissue damage to the vocal cords, cord displacement, and impaired vocal cord movement, clinically presenting with breathing difficulties, hoarseness, and choking during swallowing. Laryngoplasty is recommended to reconstruct the cricoarytenoid joint, realign the vocal cords, and restore tension. Intraoperatively, it is essential to protect normal laryngeal mucosa and minimize submucosal exposure to effectively prevent laryngeal stenosis. In subglottic and tracheal injuries, the primary goal is to prevent postoperative airway collapse while maintaining anatomical integrity. Internal fixation is commonly applied to support structures, including the cricoid cartilage. Laryngotracheal ruptures are life-threatening, and airway patency must be ensured. Emergency tracheostomy is required to locate the trachea, and care should be taken to reduce tension in the alignment sutures. Blunt dissection around the trachea can be used to reduce tension. Postoperatively, hyperextension of the neck should be prevented to avoid retearing. Some researchers recommend using a temporary suture between the mandible and sternum to prevent hyperextension of the neck during surgery [8]. For patients with neck trauma and tracheal injury, early, adequate, and full-dose antibiotic therapy is essential. In addition, metabolic factors, including blood sugar levels, must be controlled to enhance wound healing. Herein, one patient with diabetes developed a postoperative pharyngeal leak that healed after prolonged dressing changes, leading to an extended hospital stay and reduced quality of medical care. Adjunctive physical therapy may also facilitate circulation and wound healing. Cervical immobilization, especially in patients with spinal injuries, is another factor that affects prognosis.

Conclusion

Neck trauma involving laryngeal and tracheal injuries is a complex and urgent clinical condition with an unpredictable prognosis. Clinicians should be vigilant for occult laryngeal and tracheal injuries during diagnosis. Preoperative imaging studies and fiberoptic endoscopy should be performed to confirm this condition. Intraoperative exploration is recommended for suspected laryngeal or tracheal injuries. Early surgery is more effective in preventing postoperative scar stenosis and preserving laryngeal and tracheal function. This study demonstrates that prompt, effective, and personalized treatment of compound neck injuries with laryngeal and tracheal injuries can maximize the protection of respiratory, vocal, and swallowing functions.

Funding

This work was supported by the 2020 Self-Funded Science and Technology Project of Fuyang City (Project Number: FX202081033).

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Professors Xinghong Yin and Maoli Duan for their guidance and Fan Bai for data collection. We also thank the 2024 Health and Wellness Research Project of Fuyang City for sponsorship.

References

- Nepogodiev D, Martin J, Biccard B, Ademuyiwa A, Bhangu A. Making all deaths after surgery count - Authors' reply. Lancet. 2019; 393: 2588-2589.

- Sethi RKV, Khatib D, Kligerman M, Kozin ED, Gray ST, Naunheim MR. Laryngeal fracture presentation and management in United States emergency rooms. Laryngoscope. 2019; 129: 2341-2346.

- Pincet L, Lecca G, Chrysogelou I, Sandu K. External laryngotracheal trauma: a case series and an algorithmic management strategy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2024; 281: 1895-1904.

- Randall DR, Rudmik LR, Ball CG, Bosch JD. External laryngotracheal trauma: Incidence, airway control, and outcomes in a large Canadian center. Laryngoscope. 2014; 124: E123-E133.

- Shiroff AM, Gale SC, Martin ND, Marchalik D, Petrov D, Ahmed HM, et al. Penetrating neck trauma: a review of management strategies and discussion of the 'No Zone' approach. Am Surg. 2013; 79: 23-29.

- Antonescu I, Mani VR, Agarwal S. Traumatic injuries to the trachea and bronchi: a narrative review. Mediastinum. 2022; 6: 22.

- Sethi RK, Kozin ED, Fagenholz PJ, Lee DJ, Shrime MG, Gray ST. Epidemiological survey of head and neck injuries and trauma in the United States. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014; 151: 776-784.

- Elias N, Thomas J, Cheng A. Management of Laryngeal Trauma. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2021; 33: 417-427.

- Lieder A, Wilson J. Re: 'An evidence-based review of the assessment and management of penetrating neck trauma'. Clin Otolaryngol. 2012; 37: 245.

- Go JL, Acharya J, Branchcomb JC, Rajamohan AG. Traumatic Neck and Skull Base Injuries. Radiographics. 2019; 39: 1796-1807.

- Moonsamy P, Sachdeva UM, Morse CR. Management of laryngotracheal trauma. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2018; 7: 210-216.