Diagnosis of Advanced Multimetastatic Lung Cancer by Discovery of Orofacial Metastasis: A Case Report

- 1. University Hospital of Montpellier, Montpellier University, Montpellier, France

Citation

Lassaux V, Donadon E, Guégan B, De Boutray M, Pierre G, et al. (2025) Diagnosis of Advanced Multimetastatic Lung Cancer by Discovery of Orofacial Metastasis: A Case Report. Ann Otolaryngol Rhinol 12(1): 1351.

INTRODUCTION

Metastases to the oral cavity from extra-oral primary lesions are exceedingly rare, accounting for only 1–3% of all malignant oral tumors, with the mandibular bone being the most commonly affected site [1,2]. Isolated oral tissue metastases are even less common [3], particularly those involving only soft tissue, as demonstrated by Servato et al. [4], where only 2 of 24 cases presented with isolated soft tissue involvement.

Oral metastatic lesions are predominantly located in the attached gingiva (57%), followed by the tongue (27%), tonsils (8%), palatal mucosa (4%), lips (3%), and floor of the mouth mucosa (<1%) [5]. Cervical lymph nodes are frequently involved (70.8% of cases, per Servato et al. [4]), and their involvement is an unfavorable prognostic factor, particularly in breast and lung cancers [4-6]. Hirsberg et al., suggest that the primary site of carcinoma varies by sex: in men, the lung (35.5%), kidney (16%), and skin (15%) are most commonly implicated, whereas in women, the breast (24%) and genital organs (17%) are the leading sites [5].

Epithelial tumors constitute the majority (83%) of oral metastases [4-7], with adenocarcinoma being the most prevalent histological form. Other forms, such as Ewing’s sarcoma, melanoma, neuroblastoma, leiomyosarcoma, and pheochromocytoma, have also been reported [4-7].

The synchrony between oral and extra-oral metastatic lesions is often elusive, with studies indicating an absence of head and neck malignancy diagnosis during initial consultations [4-6]. Delayed diagnosis significantly increases the risk of tissue invasion, diminishing the prognosis for functional maxillofacial reconstruction and reducing overall survival due to the progression and dissemination of the primary lesion [6-10]. In advanced cases, representing 8.3% of Servato et al.’s cohort [4], palliative care and analgesic management become the primary focus, with a mean survival time of only 7 months [6].

This report presents a rare case of primary pulmonary cancer with oral and extra-oral metastatic involvement and emphasizes the critical importance of comprehensive oral examinations for early detection and improved patient outcomes.

OBSERVATION

A 60-year-old patient was referred to the oral surgery department by his dentist due to a persistent alveolar healing defect following extractions performed six months earlier. The patient’s medical history included a 40-pack year smoking habit but no other notable health issues. The patient reported only hypoesthesia in the right cheek, corresponding to the maxillary nerve (V2) territory.

Clinical examination revealed right-sided facial swelling extending to the eye, previously treated with antibiotics (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Slight right facial swelling lingering after antibiotic therapy

A fixed right submandibular lymphadenopathy was palpable, and palpation of the right nasolabial fold elicited pain. Intraoral examination showed a raw gingival lesion spanning the entire gingival ridge, from the maxillary third molar to the ipsilateral canine. The lesion deformed the palatal mucosa and bled upon light contact with a mirror (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Gingival lesion at the origin of the consultation, bleeding on contact

The surrounding remaining teeth exhibited terminal mobility.

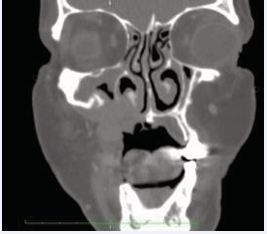

CBCT imaging identified a 3.5 × 2.5 × 2.5 cm right maxillary mass invading the sinus and nasal cavity (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Frontal CBCT section, showing a right maxillary mass invading the sinus and nasal cavity

Given the patient’s history of heavy tobacco use and the clinical suspicion of malignancy, the case was referred to the ENT department for further staging.

Facial MRI revealed an infiltrative lesion in the right maxillary bone with minimal extension into the right nasal fossa, maxillary sinus floor, and oral cavity, sparing adjacent tissues (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Frontal MRI section, showing an infiltrating lesion of the right maxillary bone, with extension into the right nasal cavity, the floor of the maxillary sinus and the oral cavity.

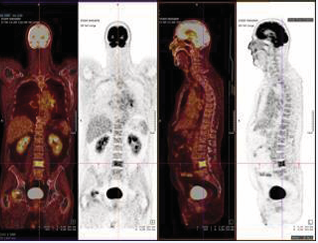

A week later, additional investigations, including pan-endoscopy, cerebral CT scan, PET scan, and histopathological analysis, confirmed the diagnosis of stage IV pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Multiple secondary lesions were detected in the brain, cervical lymph nodes, right humeral head, left clavicle, ribs, D7 and L4 vertebrae, right femoral head, upper third of the left femur, and the right adrenal gland (Figure 5).

Figure 5 PET scan on which the primary and secondary lung lesions are visible

The patient began palliative chemotherapy (cisplatin and pemetrexed) one month later, accompanied by analgesic radiotherapy targeting the right hip. Treatment with Denosumab was also initiated to address the extensive metastatic bone involvement.

DISCUSSION

In rare cases, oral metastatic lesions may be the initial manifestation of an extra-oral primary cancer, and even more rarely, of multi-metastatic lung adenocarcinoma. Hirshberg et al. [6], reported that in a quarter of the 367 patients studied, oral lesions were the first diagnosed signs of an extra-oral primary malignancy. This underscores the critical importance of thorough oral clinical examinations and vigilance for malignant signs in oral cavity lesions.

Patients who do not exhibit systemic symptoms or complain about their general health often present asymptomatic gingival lesions, which are easily mistaken for benign reactive conditions, such as hemangiomas or granulomas [5-11]. Moreover, metastatic oral lesions typically resemble hyperplastic or inflammatory lesions rather than the ulcerated lesions commonly associated with primary oral malignancies; the latter are reported in only 10% of cases [5]. The low prevalence of oral metastatic lesions compared to primary malignancies (e.g. squamous cell carcinoma) further contributes to delayed diagnoses in the absence of systematic staging. Interestingly, in 20.4% of cases, oral metastatic lesions are identified before the primary tumor [4], and for 25% of patients with extra-oral cancers, the oral cavity is the first site of metastasis [5]. In line with the present case, the lung is the most common primary site of origin, often affecting both the jawbone (22%) and oral mucosa (31.3%) [6].

Histopathological examination of metastases, including specific marker analysis, is crucial to accurately identify the primary site. Misdiagnosis as a primary oral malignancy is common, especially given the histological similarities between primary intraoral squamous cell carcinoma and metastatic squamous cell carcinoma from the lung [3]. Delayed diagnoses are often linked to the absence of biopsies and a lack of awareness of severe clinical signs. This highlights the need for improved initial and continuing education in oral dermatology across the medical community.

Lymph node involvement, as well as combined bone and mucosal involvement driven by osteolytic and angiogenic processes, are critical warning signs [3-5]. On average, a primary cancer linked to an oral metastasis is diagnosed after 40 months, with delays extending up to 10 years [3]. In the present case, the patient was referred to a specialist only 8 months after the initial symptoms, which were misdiagnosed as benign. Post-extraction healing failure was a common reason for consultation, as noted in Hirshberg’s study, which reported 56 such cases among 673 patients [6].

Even after detecting an oral metastatic lesion, whole body evaluation using PET scans is essential for accurate identification of the primary tumor and other metastases, outperforming conventional imaging techniques

Management of multi-metastatic adenocarcinoma heavily depends on the stage of the disease. In advanced cases, palliative radiotherapy is the preferred treatment due to its efficacy in relieving pain caused by secondary bone lesions, thereby improving patients’ quality of life [12-14]. Oral metastatic involvement is a strong prognostic indicator. Studies estimate an average survival of 7 months following the detection of oral metastases [3-6], with prognosis worsening as the number of metastatic sites increases. Complications such as bone pain, hypercalcemia, fractures, and spinal cord compression, collectively referred to as skeletal-related events (SRE), significantly increase morbidity and further reduce survival rates.

CONCLUSION

The detection of suspicious oral lesions is crucial, particularly in patients with known risk factors such as smoking or poor oral hygiene, as it may uncover underlying extra-oral primary cancers. Similarly, consistent and meticulous oral examinations in patients with an existing extra-oral cancer enable the early identification of metastatic lesions in the oral cavity, which are associated with a poor prognosis.

REFERENCES

- van der Waal RI, Buter J, van der Waal I. Oral metastases: report of 24 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003; 41: 3-6.

- Thiele OC, Freier K, Bacon C, Flechtenmacher C, Scherfler S, SeebergerR. Craniofacial metastases: a 20-year survey. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2011; 39: 135-137.

- Hirshberg A, Berger R, Allon I, Kaplan I. Metastatic tumors to the jaws and mouth. Head Neck Pathol. 2014; 8: 463-474.

- Servato JP, de Paulo LF, de Faria PR, Cardoso SV, Loyola AM. Metastatic tumours to the head and neck: retrospective analysis from a Brazilian tertiary referral centre. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013; 42: 1391-1396.

- Hirshberg A, Leibovich P, Buchner A. Metastases to the oral mucosa: analysis of 157 cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1993; 22: 385-390.

- Davis RS, Flynn MB, Moore C. An unusual presentation of carcinoma of the lung: 26 patients with cervical node metastases. J Surg Oncol. 1977; 9: 503-507.

- Jham BC, Salama AR, McClure SA, Ord RA. Metastatic tumors to the oral cavity: a clinical study of 18 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2011; 5: 355-358.

- Riihimäki M, Hemminki A, Fallah M, Thomsen H, Sundquist K,

Sundquist J, et al. Metastatic sites and survival in lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2014; 86: 78-84.

- Hirshberg A, Shnaiderman-Shapiro A, Kaplan I, Berger R. Metastatic tumours to the oral cavity - pathogenesis and analysis of 673 cases. Oral Oncol. 2008; 44: 743-752.

- Nuyen B. Gingival Metastasis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Perm J. 2015.

- Jaguar GC, Prado JD, Soares F, Alves FA, Toleda Osório CA. Gingival metastasis from non- small cell undifferentiated carcinoma of the lung mimicking a pyogenic granuloma. Oral Oncol Extra. 2006; 42: 36.

- Jiang L, Mino-Kenudson M, Roden AC, Rosell R, Molina MÁ, Flores RM, et al. Association between the novel classification of lung adenocarcinoma subtypes and EGFR/KRAS mutation status: A systematic literature review and pooled-data analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019; 45: 870-876.

- Chen N, Fang W, Lin Z, Peng P, Wang J, Zhan J, et al. KRAS mutation- induced upregulation of PD-L1 mediates immune escape in human lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017; 66: 1175-1187.

- Nielsen OS. Present status of palliative radiotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2001; 37: S279-S288.