Flexible Endoscopic Diagnosis of Fourth Branchial Cleft Sinus in Children A Case Series

- 1. Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, The Hebrew University, Israel

- 2. Pediatric Pulmonary Institute, The Hebrew University, Israel

Abstract

Objectives: Fourth branchial cleft anomalies are rare and often misdiagnosed. They typically present as sinus tracts opening into the pyriform sinus. Diagnosis is traditionally confirmed using barium swallow or rigid laryngoscopy, both of which have limitations. This study highlights the advantages of flexible fiberoptic endoscopy for direct visualization of the tract opening—an essential step for accurate diagnosis— while avoiding radiation exposure and the need for rigid instrumentation.

Methods: We retrospectively reviewed seven pediatric cases referred to our tertiary medical center between 2020 and 2024. All children presented with cervical infections and were ultimately diagnosed with fourth branchial cleft sinus.

Results: The series included seven children (five boys, two girls), aged 1 to 13 years. All had left-sided sinus tracts. Six children presented with a first episode of neck infection; one had a recurrent episode. In every case, diagnosis was confirmed by direct visualization of the tract opening in the pyriform sinus using flexible fiberoptic endoscopy. All patients were treated with endoscopic diathermy cauterization. One child experienced recurrent infection, suggesting procedural failure.

Conclusion: Diagnosis of fourth branchial cleft sinus relies on identifying the internal tract opening. Flexible endoscopy offers a safe, minimally invasive, and radiation-free method for achieving this, with the added benefit of being feasible in awake or lightly sedated children. Further studies are warranted to assess the effectiveness of tract cauterization using flexible endoscopy equipped with a working channel.

Keywords

• Fourth Branchial Cleft Sinus; Flexible Endoscopy; Thyroiditis

Citation

Hadar A, Picard E, Joseph L, Shaul C, Sichel JY, et al. (2025) Flexible Endoscopic Diagnosis of Fourth Branchial Cleft Sinus in Children: A Case Series. Ann Otolaryngol Rhinol 12(4): 1367.

ABBREVIATIONS

ED: Emergency Department; US: Ultrasound; CT: Computed Tomography; OR: Odds ratio; SCM: Sternocleidomastoid; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging

INTRODUCTION

Branchial cleft anomalies are congenital remnants of embryologic development in the neck, first described over a century ago [1]. Of the four recognized types, second branchial cleft anomalies are the most common [2,3]. The rare fourth branchial cleft remnant typically extends from the apex of the pyriform sinus toward the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM), often passing near the aortic arch on the left or the subclavian artery on the right. This anomaly is frequently misdiagnosed and typically present as sinus tracts with openings into the pyriform sinus, most commonly on the left side [4,5]. Fourth branchial cleft anomalies may present as ‘cysts’ (with no external or internal opening- neither to the skin, nor to the pharynx), ‘sinuses’ (with a single internal or external opening), or ‘fistulas’ (with both internal and external openings). Accurate diagnosis involves three key components.

Clinical Suspicion

These anomalies often present as abscesses in the lower neck, particularly near the thyroid gland, and may mimic suppurative thyroiditis [2-6]. Initial presentations frequently require incision and drainage. A high index of suspicion, based on clinical awareness and comprehensive understanding of this particular pathology is essential for quick and accurate diagnosis.

Imaging

When suspected, a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan may demonstrate a deep neck abscess adjacent to but separate from the thyroid gland, occasionally with a hypodense tract traversing the gland and extending toward the pyriform sinus. Additional findings may include medial displacement of the adjacent vascular structures (the carotid artery and internal jugular vein), flattening of the pyriform sinus, and intraluminal air bubbles along the suspected tract.

Diagnostic Confirmation

Confirmation relies on identification of the sinus tract by either barium swallow or rigid direct laryngoscopy [7]. Barium swallow studies have traditionally been used but are limited by low sensitivity and radiation exposure. Direct visualization of the internal sinus tract opening by rigid direct laryngoscopy remains the gold standard for diagnosis [6-9], yet it typically requires general anesthesia and carries risks of trauma to the airway. In this study, we present our experience using flexible fiberoptic endoscopy in the outpatient setting to visualize the tract opening. This technique is convenient, avoids the need for general anesthesia, is less traumatic than rigid laryngoscopy, and can be performed even in patients with restricted mouth opening.

CASE PRESENTATION

We retrospectively reviewed a series of pediatric cases referred to our tertiary medical center between 2020 and 2024. All children presented with neck infections and were ultimately diagnosed with fourth branchial cleft sinus. Diagnosis in each case was based on clinical and radiologic suspicion and confirmed by direct visualization of the tract opening via flexible endoscopy.

Procedure Details

Flexible endoscopy was performed by a multidisciplinary team comprising a pediatric otolaryngologist, pediatric pulmonologist, pediatric anesthesiologist, nurse, and technician. Anesthesia was induced and maintained using inhaled sevoflurane, with intravenous propofol added selectively to deepen sedation. No airway adjuncts (e.g., laryngeal masks or naso/oropharyngeal airways) or muscle relaxants were used. A flexible bronchoscope (Olympus BF-3C160, 3.8 mm for 4 younger children; BF- P190, 4.1 mm for 3 older children) was lubricated with lidocaine gel and introduced via the nasal passage. After full visualization of the larynx, 1% lidocaine was administered through the working channel for local anesthesia (up to a maximum dose of 7 mg/kg).

The tract opening was typically identified as a flange- or fold-like structure medial to the sinus opening and lateral to the upper esophageal sphincter [10,11]. Gentle insufflation of oxygen at 1 L/min through the working channel aided in dilating the sinus opening to facilitate visualization.

Treatment Approach

All patients underwent endoscopic cauterization of the tract using diathermy (Bugbee® electrode, Laborie Medical Inc., Williston, VT, USA). This technique serves as a minimally invasive alternative to traditional open surgical excision [8,12,13]. Due to the rarity of the condition, representative radiological images are included to illustrate key diagnostic features. The institutional review board approved this retrospective case series and waived the requirement for individual patient consent.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Course

The cohort comprised seven children (five boys and two girls) aged 1–13 years. All had left-sided sinus tracts. Six patients presented with a first episode of neck infection; one experienced a recurrence. The interval between initial presentation and definitive diagnosis is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Patients Detail.

|

Patient |

Age at Presentation (years) |

Clinical Presentation |

Time to Diagnosis |

|

1 |

1.5, 3.5 |

Recurrent left neck swelling |

1.5 months |

|

2 |

3 |

Left anterior cervical swelling |

2 weeks |

|

3 |

5 |

Deep left cervical abscess |

2 months |

|

4 |

11 |

Left thyroid lobe swelling |

2 months |

|

5 |

13 |

Deep left cervical abscess |

1 month |

|

6 |

2.5 |

Left anterior cervical swelling |

2 days |

|

7 |

10 |

Supraglottic edema |

2 years |

Case 1

A 1.5-year-old boy was referred to the emergency department (ED) with left-sided neck swelling. Ultrasound (US) revealed a 4 cm collection. A subsequent CT scan showed an abscess in the left neck, medial to the carotid artery, causing mild tracheal compression and displacement of the thyroid gland. The patient received intravenous antibiotics and underwent aspiration, leading to clinical improvement. At age 3.5 years, the child was readmitted with recurrent neck swelling. Flexible endoscopy identified an opening in the left pyriform sinus consistent with a fourth branchial cleft sinus. Endoscopic diathermy cauterization was performed under general anesthesia. A follow-up barium swallow confirmed complete resolution with no contrast leakage.

Case 2

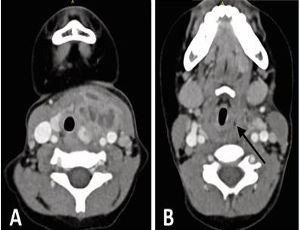

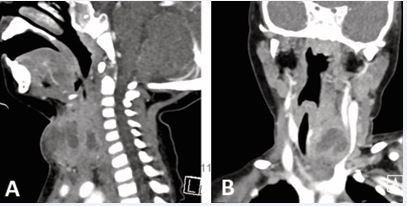

A 3-year-old girl presented with anterior neck swelling near the thyroid gland, slightly left of midline. CT revealed a 2.5 cm deep abscess within the SCM, with a hypodense tract traversing the left thyroid lobe (Figure 1A),and a suspected opening into the pyriform sinus (Figure 1B).

Figure 1 (A) Axial CT showing a left-sided abscess with a hypodense tract traversing the thyroid lobe, medial to major vessels. (B) Suspected internal opening in the left pyriform sinus (arrow).

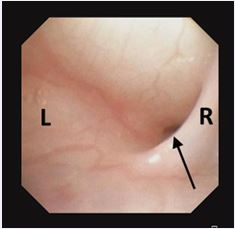

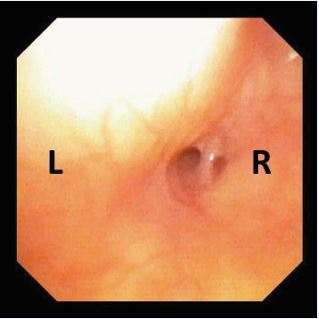

Flexible endoscopy confirmed the sinus tract, aided by visualization of a characteristic mucosal fold (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Flexible endoscopy showing an internal opening in the left pyriform sinus. A mucosal fold medial to the opening (arrow) helped localize the tract.

The tract was treated successfully with endoscopic cauterization under general anesthesia.

Case 3

A 5-year-old boy presented with left-sided neck swelling. CT demonstrated a hypodense focus in the left thyroid lobe, with air bubbles adjacent to the pyriform sinus (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Axial CT demonstrating a hypodense focus in the left thyroid lobe with adjacent air bubbles near the pyriform sinus.

Flexible endoscopy confirmed a sinus tract, which was cauterized using diathermy. One year later, the child developed recurrent infection at the same site, indicating treatment failure. A second cauterization was performed, with no recurrence during two years of follow-up.

Case 4

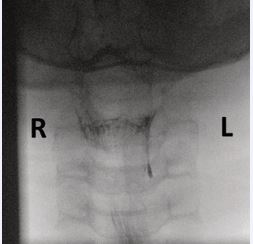

An 11-year-old boy presented with a tender swelling on the left side of the neck at the level of the thyroid. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a small effusion within the thyroid gland and an abnormality in the left pyriform sinus. A subsequent barium swallow showed a contrast-filled tract extending 1.6 cm from the apex of the left pyriform sinus (Figure 4). Flexible endoscopy confirmed the internal opening, which was successfully cauterized under general anesthesia.

Figure 4 Barium swallow revealing a contrast-filled tract extending from the apex of the left pyriform sinus.

Case 5

A 13-year-old girl was referred for evaluation of a non-tender, firm mass in the left neck. MRI revealed involvement of the thyroid gland, the left pyriform sinus, and surrounding strap muscles, along with lateral compression of adjacent vascular structures. Flexible endoscopy confirmed the presence of a pyriform sinus opening (Figure 5), and the tract was closed via endoscopic cauterization.

Figure 5 Endoscopic view of the internal opening in the left pyriform sinus.

Case 6

A healthy 2.5-year-old boy presented with five days of fever and cough followed by the development of anterior neck swelling. Physical examination revealed a large, tender, firm mass with slight skin discoloration. US demonstrated a 4×4 cm multiloculated collection within the left thyroid lobe with possible air bubbles. CT showed an extensive inflammatory process with a collection extending toward the left pyriform sinus, posteriorly abutting the esophagus, and causing rightward tracheal deviation and left jugular vein compression (Figure 6A,6B). The child underwent drainage under general anesthesia. Flexible laryngoscopy performed within two days confirmed the diagnosis of a fourth branchial cleft sinus by visualizing the tract opening in the pyriform sinus.

Figure 6 (A) Sagittal CT showing inflammation and edema involving the subcutaneous fat of the anterior neck. (B) Coronal CT showing compression of the left jugular vein and rightward tracheal deviation.

Case 7

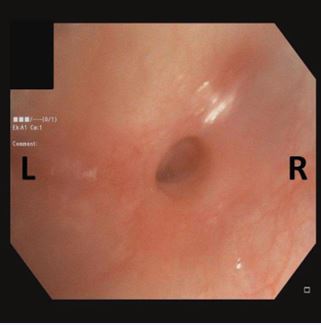

A 10-year-old boy was referred after two weeks of left sided neck swelling, fever, odynophagia, and hoarseness. Nasoendoscopy revealed supraglottic edema. US showed a 2.5 cm parapharyngeal infection involving the left thyroid lobe, without a defined collection. The child was admitted for observation and treated with systemic antibiotics and steroids, resulting in symptomatic improvement. A possible infected branchial cyst was suspected, but laryngoscopy was deferred due to loss to follow-up. Over the following two years, the child experienced two additional episodes of neck swelling with mild supraglottic involvement. During hospitalization, flexible laryngoscopy revealed a double-lumen opening in the left pyriform sinus (Figure 7). Endoscopic cauterization is planned.

Figure 7 Flexible endoscopy demonstrating a double-lumen opening in the left pyriform sinus.

DISCUSSION

This case series describes seven pediatric patients in whom the diagnosis of fourth branchial cleft sinus was confirmed via flexible endoscopy. To our knowledge, the use of flexible endoscopy alone for definitive diagnosis has not been previously reported in the literature. Fourth branchial cleft sinus is a rare congenital anomaly [1-15], frequently misdiagnosed due to its variable and non-specific clinical presentations. The tract typically originates in the apex of the pyriform sinus and may extend deeply, sometimes forming external openings or fistulas, secondary to recurrent infections or surgical interventions. However, true complete fistula with both internal and external openings has never been described [6-17]. Terminology is inconsistent in the literature; some sources describe an internal opening as a fistula, while others refer to it as a sinus, as it is located in the pyriform sinus, contributing to diagnostic ambiguity.

Most reported cases are left-sided [9-17], likely due to embryological and vascular asymmetry, including the longer course of the left tract and its descent below the aortic arch [3]. Clinically, a fourth branchial cleft sinus should be suspected in children with recurrent neck infections or episodes resembling suppurative thyroiditis. Misdiagnosis may lead to unnecessary procedures such as thyroidectomy, which does not address the underlying cause [17]. Our series demonstrates that flexible laryngoscopy, combined with gentle oxygen insufflation, can reliably identify the internal tract opening, obviating the need for rigid laryngoscopy. Flexible laryngoscopy offers several advantages, including wide availability, reduced need for general anesthesia, and avoidance of radiation exposure. This is especially valuable in pediatric patients, in whom anatomical constraints make rigid laryngoscopy more challenging and less sensitive [17]. We suggest that insufflation assists in dilating the sinus opening, improving visualization of characteristic features such as the mucosal fold or “flange” medial to the sinus opening and lateral to the upper esophageal sphincter, an anatomical landmark rarely mentioned in the literature [10-11] (Figure 2). Notably, we report for the first time a double-lumen pyriform sinus opening (Figure 7), potentially representing an anatomical variant. Flexible endoscopy may also reduce the need for imaging, particularly CT scans, which involve radiation. Ultrasound, a radiation-free modality, can aid in identifying abscesses or thyroid involvement and serve as an adjunct in evaluation, and waive the need for additional unwarranted imaging as CT.

Definitive treatment typically involves tract closure via endoscopic cauterization [12] or external neck approaches [8]. In some cases, thyroidectomy may be required, particularly when the thyroid gland is extensively involved [13]. A recent meta-analysis found that outcomes were comparable between endoscopic and open surgical approaches for both third and fourth branchial cleft anomalies [18]. In our series, endoscopic cauterization was successful in all but one case. Currently, rigid laryngoscopy is our institutional standard for treatment, while flexible endoscopy is used diagnostically. Based on our findings, we propose that flexible bronchoscopy equipped with a working channel could serve both diagnostic and therapeutic roles, offering a streamlined, minimally invasive alternative for managing this condition.

CONCLUSION

Fourth branchial cleft sinus remains a diagnostic challenge and requires direct visualization of the internal tract opening in the pyriform sinus. Flexible laryngoscopy, especially when combined with oxygen insufflation, provides a safe, accessible, and effective method for identification. This approach can minimize reliance on imaging, especially CT and simplify the diagnostic process. Future studies should evaluate the feasibility and outcomes of tract cauterization using flexible bronchoscopy with a working channel, which may further reduce the need for invasive procedures and improve patient care.

REFERENCES

- Frazer JE. The nomenclature of diseased states caused by certain vestigial structures in the neck. Br J Surg. 1923; 11:131-136.

- Adams A, Mankad K, Offiah C, Childs L. Branchial cleft anomalies: a pictorial review of embryological development and spectrum of imaging findings. Insights Imaging. 2016; 7: 69-76.

- al-Ghamdi S, Freedman A, Just N, Rochon L, Frenkiel S. Fourth branchial cleft cyst. J Otolaryngol. 1992; 21: 447-449.

- Cain RB, Kasznica P, Brundage WJ. Right-sided pyriform sinus fistula: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2012; 2012: 934968.

- Nicollas R, Ducroz V, Garabédian EN, Triglia JM. Fourth branchial pouch anomalies: a study of six cases and review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1998; 44: 5-10.

- James A, Stewart C, Warrick P, Tzifa C, Forte V. Branchial sinus of the piriform fossa: reappraisal of third and fourth branchial anomalies. Laryngoscope. 2007; 117: 1920-1924.

- Jeyakumar A, Hengerer AS. Various presentations of fourth branchial pouch anomalies. Ear Nose Throat J. 2004; 83: 640-644.

- Maksimoski M, Maurrasse SE, Purkey M, Maddalozzo J. Combination Surgical Procedure for Fourth Branchial Anomalies: Operative Technique and Outcomes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2021; 130: 738- 744.

- Nicoucar K, Giger R, Pope HG Jr, Jaecklin T, Dulguerov P. Management of congenital fourth branchial arch anomalies: a review and analysis of published cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44: 1432-1439.

- Sayadi SJ, Gassab I, Dellai M, Mekki M, Golli M, Elkadhi F, et al. Traitement endoscopique au laser des fistules de la 4e poche endobranchiale [Laser coagulation in the endoscopic management of fourth branchial pouch sinus]. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2006; 123: 138-142.

- Leboulanger N, Ruellan K, Nevoux J, Pezzettigotta S, Denoyelle F, Roger G, et al. Neonatal vs delayed-onset fourth branchial pouch anomalies: therapeutic implications. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010; 136: 885-890.

- Verret DJ, McClay J, Murray A, Biavati M, Brown O. Endoscopic cauterization of fourth branchial cleft sinus tracts. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004; 130: 465-468.

- Burstin PP, Briggs RJ. Fourth branchial sinus causing recurrent cervical abscess. Aust N Z J Surg. 1997; 67: 119-122.

- Irace A, Adil E. Embryology of congenital neck masses. Oper Tech Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2017; 28: 138-142.

- Nayan S, MacLean J, Sommer D. Thymic cyst: a fourth branchial cleft anomaly. Laryngoscope. 2010; 120: 100-102.

- Rea PA, Hartley BE, Bailey CM. Third and fourth branchial pouch anomalies. J Laryngol Otol. 2004; 118: 19-24.

- Garrel R, Jouzdani E, Gardiner Q, Makeieff M, Mondain M, Hagen P, et al. Fourth branchial pouch sinus: from diagnosis to treatment. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006; 134: 157-163.

- Derks LS, Veenstra HJ, Oomen KP, Speleman L, Stegeman I. Surgery versus endoscopic cauterization in patients with third or fourth branchial pouch sinuses: A systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2016; 126: 212-217.