Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Demographics, Incidence, and Treatment of Dog Bite-Induced Facial Trauma

- 1. Department of Surgery, University of North Carolina Hospitals, USA

- 2. Penn State College of Medicine, USA

- 3. Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, Penn State Health, USA

Abstract

Objective: The COVID-19 pandemic hindered socialization of children and animals. After a perceived initial decrease in trauma, we have anecdotally noted a rise in dog bite cases since the pandemic. This study aims to evaluate the impact of the pandemic on the incidence and treatment of dog bites to the face, head, or neck.

Methods: The TriNetX Research Network identified 208,258 patients bitten by a dog during 2017-2023. A retrospective chart review identified 663 patients presenting specifically with dog bite facial injuries at a single institution from 2017-2023. Injuries were analyzed during March-August of each year to correspond with the months of the initial pandemic lockdown in 2020 as well as across the entire year.

Results: Prior to the pandemic, there had been a steady increase in dog bite related injuries. In 2020, there was a nationwide decrease in overall rates by 4.30% with 6.40% decrease noted between March and August of that year. Conversely, during the same time at our institution, there was a 25.44% decrease in patients being seen for facial dog bites with a 36.23% decrease specifically within March-August. Bedside repairs at our institution dropped 41.38% in 2020 compared to 2019. Post-pandemic, the rates of dog bite injuries increased and reached pre-pandemic levels.

Conclusion: A steady increase in number of dog bite facial injuries was noted prior to the pandemic. The incidence decreased in 2020 nationwide followed by a rebound of injuries that reached, and often surpassed, pre-pandemic levels. Changes in the incidence, demographics, and treatment highlight the lasting changes in dog bite injuries due to social disruption.

Keywords

• Dog Bite

• Facial Trauma

• COVID-19 Pandemic

Citation

Rothka AJ, Aziz M, Nguyen KPK, Lorenz FJ, Schopper HK, et al. (2026) Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Demographics, Incidence, and Treatment of Dog Bite-Induced Facial Trauma. Ann Otolaryngol Rhinol 13(1): 1381.

INTRODUCTION

The beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic ushered in a time of vast uncertainty across the globe. Governments were telling their citizens to stay home for an unknown duration of time, which negatively impacted mental health [1]. In the United States, many turned toward purchasing or adopting a “pandemic puppy [2].” This time of social isolation prevented proper socialization of dogs. Immersing a puppy in social situations helps improve interactions between the puppy and adults, children, and other dogs [3]. In fact, one Italian study noted that puppies adopted during their lockdown (March – June 2020) were more likely to display aggressive personality traits compared to puppies adopted June 2020 – February 2021 [4]. There was a gap in the literature evaluating pre- and post-pandemic dog bite related facial trauma as the “pandemic puppies” aged and had opportunity to socialize. The aim of this study was to perform an analysis of patients with dog bite-induced facial injuries to determine trends in the incidence, demographics, and treatment of patients within this population both on a national and a local level. We further revaluated injuries specifically related to the lockdown period each year to minimize confounding by pre-existing seasonal changes to rates of dog bite injuries. We hypothesized that there would be an initial decrease in dog-bite facial injuries during and immediately following the lockdown followed by a sustained increase in injuries thereafter.

METHODS

The TriNetX Research Network database was utilized to build a cohort of patients with facial trauma induced by the bite of a dog. TriNetX is a regularly updated, deidentified database with access to more than 100 million electronic medical records from more than 100 healthcare organizations (HCOs) across the United States [5]. This database is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), ensuring the confidentiality of patient data. TriNetX was queried by selecting diagnosis (ICD-10) codes to identify patients who sought healthcare evaluation after being bitten by a dog from January 1, 2017, until December 31, 2023. The ICD-10 code of interest was W54.0XXA, “Bitten by dog, initial encounter.” Injuries were analyzed across the entire calendar year as well as during March-August of each year to correspond with the months of the initial pandemic lockdown in 2020.

Because injuries were not able to be specifically limited to the head, neck, or face on TriNetX, a retrospective chart review was also completed. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at our institution reviewed and approved the study (Study ID# 24260). Patients who presented to our institution between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2023, with dog bite-induced facial trauma were included in the study. The following data was collected, if available: age at visit, date of incident, patient sex, location of injury, number of injuries, hospital admission (yes/no), and type of repair (bedside/operative/none).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were computed on the TriNetX platform using the “Incidence and Prevalence Tool,” which employs Java, R, and Python. Time windows and outcomes were specified with ICD-10 codes. TriNetX enabled real-time analysis of patient cohorts representative of the general population. For this specific study, relative risks, 95% confidence intervals, unpaired t-tests, and associated p values were calculated to compare dog bite injuries before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

RESULTS

Database Cohort – Calendar Year

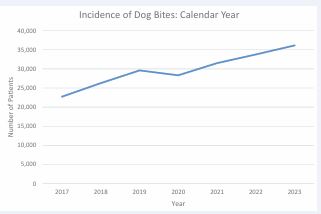

A cohort of 208,258 patients from 102 HCOs were identified on TriNetX during 2017-2023, representing the general population. Figure 1 shows the incidence of dog bite injuries. From 2017 to 2019, the incidence of dog bite injuries increased by +26.68% (p<0.001). In 2020, there was a nationwide decrease in the incidence of dog bites by -4.30% (p<0.001) compared to the preceding year. Followed by an increase of +25.42% (p<0.001) over the next 3 years (2021-2023).

Figure 1 Graphical Representation of Patients from Database with Dog Bite Injuries Before, During, and After the COVID-19 Pandemic (Calendar Years 2017-2023).

Demographic representation of the patients evaluated after sustaining a dog bite can be found in Table 1. The 0 to 4 and 5 to 9 age brackets were most affected, comprising of 9.97% and 9.94% of patients from 2017-2023, respectively. In 2020, there was a significant increase in patients within the 5 to 9 group compared to 2019 (p=0.0212). However, there were significant decreases in the number of patients in the following age groups: 50 to 54, 55 to 59, 60 to 64, 70 to 74, 75 to 79, and 85 and older (all p<0.04). The largest decrease was in the 85 and older group (-29.11%). When comparing 2021 to 2020, there were significant increases in the number of patients in all age groups except the 0 to 4 and the 5 to 9 groups (all p<0.01) with the largest increase within the 85 and older group (+41.07%). In 2022, there were significant increases in the number of patients within the 15 to 19, 20 to 24, 30 to 34, 35 to 39, 40 to 44, 50 to 54, 65 to 69, 70 to 74, and 75 to 79 age groups compared to 2021 (all p<0.02). The greatest increase occurred within the 75- to 79-year-old group (+19.61%). Compared to 2022, 2023 had significant increases in the number of patients in the 20 to 24, 25 to 29, 35 to 39, 40 to 44, 45 to 49, 60 to 64, 65 to 69, 75 to 79, and 80 to 84 age groups (all p<0.05), with the greatest increase within the 80- to 84-year-old group (+21.52%).

Table 1: Demographics of Database Patients with Dog Bite Injuries Before, During, and After the COVID-19 Pandemic (2017-2023)

|

Each RR (95% CI) and p-value compares the given year to the year prior. Bold p-values are statistically significant Abbreviations: RR = Relative Risk; CI = Confidence Interval

Data regarding patient sex is also included in Table 1. Sex was provided as female, male, or unknown. There was a slight female predominance from 2017-2023, with 50.29% of patients being female. There was a significant reduction in the number of female patients in 2020 compared to 2019 (p<0.001). In 2021, there were significant increases in both sexes (both p<0.001), with females experiencing a greater rise (+13.59% versus +7.48%). By 2022, both sexes saw significant increases, with continued increases throughout 2023 (all p<0.001).

Database Cohort – March-August of Each Year

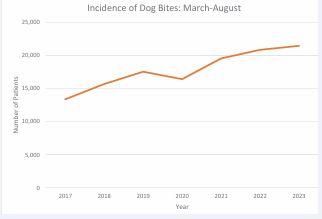

When utilizing TriNetX to analyze March-August of each year, aligning with the lockdown period of 2020, a total of 124,794 patients seeking care after a dog bite were identified. Figure 2 depicts the incidence of dog bite injuries between the months of March and August of 2017-2023. The incidence of dog bite injuries increased from March- August of 2017 to 2019 by +36.11% (p<0.001). In March- August 2020, the incidence in dog bite injuries decreased by -6.40% from March-August of 2019 (p<0.001). From March-August of 2021-2023, the incidence of dog bite injuries rebounded and increased by +28.62% (p<0.01).

Figure 2 Graphical Representation of Patients from Database with Dog Bite Injuries March-August of 2017-2023, Corresponding to the Lockdown Period.

The demographics of this cohort of patients were compiled into Table 2. The most affected age group was the 5- to 9-year-old group, which consisted of 10.70% of patients. Compared to 2019, there were significant decreases in the number of patients in the 10 to 14, 25 to 29, 60 to 64, 70 to 74, 75 to 79, and 85 and older groups (all p<0.05), with the largest decrease within the 85 and older group (-26.71%). In March-August of 2021, there were significant increases in all age groups except the 0- to 4-year-old group (all p<0.009). The greatest change from March-August of 2020 was within the 70 to 74 and 85 and older groups, which experienced a +39.26% and a+39.35% increase, respectively. March-August 2022 saw significant increases in patients of the 10 to 14, 20 to 24, 30 to 34, 35 to 39, 50 to 54, 65 to 69, and 75 to 79 groups versus 2021 (all p≤0.03). Compared to the same timeframe in 2022, March-August 2023 only had a significant change in the number of patients ages 60 to 64 with a +12.85% increase (p=0.0051).

Table 2: Demographics of Database Patients with Dog Bite Injuries during March-August of 2017-2023

|

Each RR (95% CI) and p-value compares the given year to the year prior. Bold p-values are statistically significant Abbreviations: RR = Relative Risk; CI = Confidence Interval.

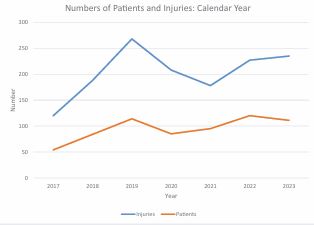

Table 2 also shows data regarding patient sex. There was a slight female predominance within March-August of each year (50.25%). There were significant reductions in patients of both sexes from March-August 2020 (both p<0.02) with a greater reduction in the number of female patients (-8.79% versus -3.57%) compared to 2019. From 2021 through 2023, there were significant increases in the number of patients of both sexes (all p <0.03), with a greater rise in female patients (+29.83%) compared to male patients (+28.56%). Institution Cohort – Calendar Year The retrospective chart review from our institution yielded a total of 663 patients with dog bite injuries to the face who sustained a total of 1,424 injuries over the study period. Figure 3 depicts the number of patients with facial dog bites and the number of injuries per year. The number of patients increased from 2017 to 2019 by +91.27% (p<0.05), and the number of injuries increased by +99.22% (p<0.001).

Figure 3 Graphical Representation of Numbers of Patients and Injuries from a Single Institution (2017-2023).

Interestingly, the highest volume of patients and injuries within the study period was in 2019 (Table 3). In 2020, both the number of patients and injuries decreased from 2019 by -25.44% and -22.39%, respectively (p<0.001 for both). In 2021, the number of patients increased by +11.76% (p=0.4325) compared to 2020; however, the number of injuries decreased by -14.42% (p<0.00l). The number of injuries continued to increase in 2022 (+27.53% from 2021, p=0.0106) and in 2023 (+3.52% from 2022, p=0.6929). Though the number of patients increased by 26.32% in 2022 compared to 2021 (p=0.0702), the number of patients decreased by 7.50% in 2023 compared to 2022 (p=0.5363).

Regarding patient age, most patients (31.67%) at our institution were of the 0- to -4-year-old age group. The mean age of patients from 2017-2023 was 15.95 years. When comparing mean age to the year prior, an unpaired t-test was performed. There were no significant differences in mean ages when analyzing the full calendar year. Given that many age groups had less than 10 patients, relative risk and percent change were not calculated.

|

Sex |

2017 |

2018 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2019 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2020 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2021 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2022 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2023 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

|

Female |

21 |

51 (+142.86%) |

2.43 (1.49- 3.97) |

<0.001 |

57 (+11.76%) |

1.12 (0.78- 1.59) |

0.539 |

48 (-15.79%) |

0.84 (0.59- 1.21) |

0.3514 |

52 (+8.33%) |

1.08 (0.75- 1.57) |

0.6718 |

56 (+7.69%) |

1.08 (0.76- 1.54) |

0.682 |

56 (0%) |

1.00 (0.71- 1.41) |

1.000 |

|

Male |

33 |

33 (0%) |

1.00 (0.63- 1.69 |

0 |

57 (+72.72%) |

1.73 (1.15- 2.60) |

0.0087 |

37 (-35.09%) |

0.65 (0.44- 0.96) |

0.0309 |

43 (+16.22%) |

1.16 (0.76- 1.77) |

0.4826 |

64 (+48.84%) |

1.49 (1.03- 2.14) |

0.0321 |

55 (-14.06%) |

0.86 (0.61- 1.20) |

0.3763 |

Each RR (95% CI) and p-value compares the given year to the year prior. Bold p-values are statistically significant Abbreviations: RR = Relative Risk; CI = Confidence Interval.

Table 3: Sex of Patients from a Single Institution Presenting with Dog Bite Injuries to the Head, Neck, or Face (2017-2023)

Patient sex was placed in Table 3. A majority of patients (51.43%) were female. In 2020, there was a significant decrease (-35.09%) in male patients from 2019 (p=0.0309). Though there was an increase in the number of male patients from 2020 to 2021, (+16.22%), it was insignificant (p=0.4826). However, in 2022, there were significantly more male patients than in 2021 (+48.84%, p=0.0321). This was followed by a decrease in male patients in 2023 (-14.05%, p=0.3763). There were no significant changes in the number of female patients year to-year from 2017-2023.

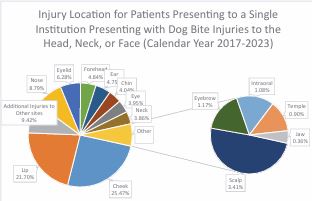

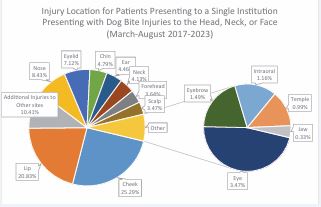

Location of injury for patients presenting from 2017 2023 was provided in Figure 4. The most common locations injured were the cheeks (25.47%); lips (21.70%); structures not within the head, neck, or face (9.42%); and nose (8.79%). Given that many structures had less than 10 patients within a year, relative risk and percent change were not calculated. Management for patients were compiled into Table 4. A total of 106 (15.99%) patients were admitted to the hospital as a result of their dog bite injuries. In 2020, there was a significant reduction in the number of patients seen that did not require hospital admission (-31.37%) compared to 2019 (p=0.0101). There were no significant differences in rates of patients that were admitted to the hospital within the study period. Regarding specific management of the injuries, 68.48% required bedside repair, 15.54% required operative repair, and 16.89% had injuries that were managed conservatively. Of note, some patients underwent multiple management methods. In 2020, there was a significant reduction in the number of patients requiring bedside repair compared to 2019 (-41.38%, p=0.0013). There were no other significant changes in management of injuries following the pandemic.

Figure 4 Injury Location for Patients Presenting to a Single Institution Presenting with Dog Bite Injuries to the Head, Neck, or Face (Calendar Year 2017-2023).

Table 4: Rates of Hospital Admission and Management at a Single Institution for Patients with Dog Bite Injuries to the Head, Neck, or Face (2017-2023).

|

Hospital Admission |

2017 |

2018 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2019 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2020 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2021 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2022 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2023 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

|

Yes |

12 |

12 (0%) |

1.00 (0.46- 2.16) |

0 |

12 (0%) |

1.00 (0.46- 2.16) |

0 |

15 (+25.00%) |

1.25 (0.61- 2.58) |

0.5466 |

18 (+20.00%) |

1.20 (0.63- 2.29) |

0.5812 |

19 (+5.56%) |

1.06 (0,58- 1.93) |

0.8609 |

18 (-5.26%) |

0.95 (0.53- 1.73) |

0.8609 |

|

No |

42 |

72 (+71.43%) |

1.71 (1.19- 2.47) |

0.004 |

102 (+41.67%) |

1.42 (1.07- 1.88) |

0.0163 |

70 (-31.37%) |

0.69 (0.52- 0.91) |

0.0101 |

77 (+10.00%) |

1.10 (0.81- 1.50) |

0.5435 |

101 (+31.17%) |

1.31 (0.99- 1.73) |

0.0564 |

93 (-7.92%) |

0.92 (0.71- 1.20) |

0.5384 |

|

Management |

2017 |

2018 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2019 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2020 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2021 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2022 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2023 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

|

Bedside Repair |

29 |

57 (+96.56%) |

1.97 (1.28- 3.03) |

0.0022 |

87 (+52.63%) |

1.53 (1.11- 2.09) |

0.0083 |

51 (-41.38%) |

0.59 (0.42- 0.81) |

0.0013 |

68 (+33.33%) |

1.33 (0.94- 1.88) |

0.1021 |

85 (+25.00%) |

1.25 (0.93- 1.68) |

0.1422 |

77 (-9.41%) |

0.91 (0.68- 1.21) |

0.4992 |

|

Operative Repair |

11 |

10 (-9.09%) |

0.91 (0.40- 2.08) |

0.821 |

12 (+20.00%) |

1.20 (0.54- 2.69) |

0.6582 |

19 (+58.33%) |

1.58 (0.80- 3.14) |

0.1891 |

15 (-21.05%) |

0.79 (0.41- 1.49) |

0.4673 |

19 (+26.67%) |

1.27 (0.67- 2.40) |

0.4673 |

17 (-10.53%) |

0.89 (0.48- 1.65) |

0.7223 |

|

Conservative Management |

14 |

18 (+28.57%) |

1.29 (0.66- 2.50) |

0.4587 |

15 (-16.67%) |

0.833 (0.44- 1.60) |

0.5829 |

17 (+13.33%) |

1.13 (0.59- 2.19) |

0.7103 |

12 (-29.41%) |

0.71 (0.35- 1.43) |

0.3344 |

18 (+50.00%) |

1.50 (0.75- 3.01) |

0.2551 |

18 (0%) |

1.00 (0.54- 2.85) |

0 |

Each RR (95% CI) and p-value compares the given year to the year prior. Bold p-values are statistically significant Abbreviations: RR = Relative Risk; CI = Confidence Interval.

Institution Cohort – March-August of Each Year

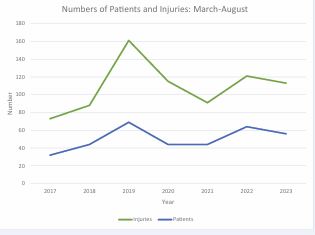

When specifically looking at March-August of each year at our institution, a total of 352 sustaining 762 injuries were identified. Figure 5 depicts the number of patients with facial dog bites and the number of injuries within March-August 2017-2023. As with the full calendar year, March-August of 2019 had the highest volume of patients and injuries. In March-August 2020, there were significant reduction in the number of patients (-36.23%) and injuries (-28.57%) compared to the same times in 2019 (both p<0.02).

Figure 5 Graphical Representation of the Numbers of Patients and Injuries during March-August of 2017-2023 at a Single Institution.

March-August 2021 had a further decrease in injuries (-20.87%, p=0.0802) from 2020, though there were no differences in the number of patients. In March August 2022, there were significant increases in both the number of patients (+45.45%) and injuries (+32.97%) compared to March-August 2021 (p<0.05 for both). This same timeframe of 2023 had reduced rates of patients (-12.50%, p=0.5806) and injuries (-6.61%, p=4359) compared to 2022. Children ages 0-4 and 5-9 had the highest incidence of dog bites within March-August at our institution, accounting for 28.98% and 29.26% of cases, respectively. The mean age of all patients was 15.81 years. When comparing mean patient age to the year prior, the mean age of patients injured March-August of 2020 (21.80) was significantly greater than the mean age of patients in March-August 2019 (12.48) (p=0.0174). Otherwise, there were no significant changes in mean age between years. Given that many age groups had less than 10 patients, relative risk and percent change were not calculated.

Table 5: Sex of Patients from a Single Institution Presenting with Dog Bite Injuries to the Head, Neck, or Face (March-August 2017-2023).

|

Sex |

2017 |

2018 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2019 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2020 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2021 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2022 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2023 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

|

Female |

13 |

29 (+123.08%) |

2.23 (1.20- 4.16) |

0.0115 |

33 (+13.79%) |

1.14 (0.72- 1.80) |

0.5785 |

27 (-18.18%) |

0.82 (0.51-- 1.30) |

0.3991 |

23 (-14.81%) |

0.85 (0.51- 1.43) |

0.544 |

34 (+47.83%) |

1.48 (0.91- 2.41) |

0.117 |

28 (-17.65%) |

0.82 (0.52- 1.30) |

0.4053 |

|

Male |

19 |

15 (-21.05%) |

0.79 (0.42- 1.50) |

0.4703 |

36 (+140.00%) |

2.40 (1.37- 4.21) |

0.0023 |

17 (-52.78%) |

0.47 (0.28- 0.81) |

0.006 |

20 (+17.65%) |

1.18 (0.64- 2.16) |

0.6012 |

30 (+50.00%) |

1.50 (0.89- 2.53) |

0.1287 |

28 (-6.67%) |

0.93 (0.58- 1.49) |

0.7725 |

Each RR (95% CI) and p-value compares the given year to the year prior. Bold p-values are statistically significant Abbreviations: RR = Relative Risk; CI = Confidence Interval.

The sex of patients presenting to our institution for facial dog bite injuries within March-August of 2017 2023 were provided in Table 5. A majority of patients (53.13%) were female. In 2020, there was a significant decline in the number of male patients compared to 2019 (-52.78%) (p=0.006). This number rebounded in 2021(+17.65% from 2020, p=0.6012) and continued to increase in 2022 (+50.00% from 2021, p=0.1287). In 2023, there was a slight reduction in the number of male patients (-6.67%, p=0.7725). As for female patients, there was a decline in 2020 (-18.18% from 2019, p=0.3991) and in 2021 (-14.81% from 2020, p=0.5440). Similarly to the male cohort, an increase in female patients occurred in 2022 (+47.83%, p=0.1170) followed by a decline in 2023 (-17.65% from 2022, p=0.4053).

Injury locations were listed in Figure 6. The most frequently injured locations within March-August of each year were the cheeks (25.29%); lips (20.83%); structures not within the head, neck, or face (10.41%); and nose (8.43%). Since many structures had less than 10 patients with injuries per year, relative risk and percent change were not calculated.

Figure 6 Injury Location for Patients Presenting to a Single Institution Presenting with Dog Bite Injuries to the Head, Neck, or Face (March August 2017-2023).

Management trends for this cohort of patients were organized into Table 6. A total of 55 patients (15.63%) with facial dog bites were admitted to the hospital due to their injuries. In March-August 2020, there were significantly fewer patients that were evaluated that did not require hospital admission (39.68% decrease from 2019) (p=0.0073). However, there were no significant changes in the number of patients overall admitted to the hospital throughout the study period. In terms of managing patient injuries, 69.03% required bedside repair, 16.48% required operative repair, and 15.34% had injuries managed conservatively. Of note, some patients underwent multiple management methods. In 2020, there was a significant decrease in the number of patients receiving bedside repair of injuries compared to 2019 (-48.15%, p=0.0022). The number of bedside repairs increased in 2021 (+25.00% from 2020, p=0.3459) and in 2022 (+40.00% from 2021, p=0.0955). This was followed by a decrease in bedside repairs in 2023 (-30.61%) compared to 2022 (p=0.0731). Though there were no significant changes in rates, March August of 2023 had the highest volume (n=14/58, 24.24%) of operative repair compared to the other years of interest.

Table 6: Rates of Hospital Admission and Management at a Single Institution for Patients with Dog Bite Injuries to the Head, Neck, or Face (March-August 2017-2023).

|

Hospital Admission |

2017 |

2018 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2019 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2020 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2021 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2022 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2023 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

|

Yes |

6 |

7 (+16.67%) |

1.17 (0.42- 3.25) |

0.768 |

6 (-14.29%) |

0.86 (0.31- 2.39) |

0.768 |

6 (0%) |

1.00 (0.34- 2.91) |

1.00 |

7 (+16.67%) |

1.17 (0.42- 3.25) |

0.768 |

10 (+25.00%) |

1.43 (0.59- 3.48) |

0.4325 |

13 (+30.00%) |

1.30 (0.62- 2.71) |

0.4841 |

|

No |

26 |

37 (+42.31%) |

1.42 (0.88- 2.29) |

0.1455 |

63 (+70.27%) |

1.70 (1.17- 2.47) |

0.0051 |

38 (-39.68%) |

0.60 (0.42- 0.87) |

0.0073 |

36 (-5.26%) |

0.95 (0.62- 1.45) |

0.8038 |

54 (+50.00%) |

1.50 (1.02- 2.22) |

0.0415 |

43 (-20.37%) |

0.80 (0.55- 1.15) |

0.2237 |

|

Management |

2017 |

2018 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2019 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2020 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2021 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2022 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

2023 (% Change) |

RR (95% CI) |

p-value |

|

Bedside Repair |

17 |

26 (+52.94%) |

1.53 (0.85- 2.75) |

0.1545 |

54 (+107.69%) |

2.08 (1.35- 3.20) |

<0.001 |

28 (-48.15%) |

0.52 (0.34- 0.79) |

0.0022 |

35 (+25.00%) |

1.25 (0.79- 1.99) |

0.3459 |

49 (+40.00%) |

1.40 (0.94- 2.08) |

0.0955 |

34 (-30.61%) |

0.69 (0.47- 1.03) |

0.0731 |

|

Operative Repair |

6 |

8 (+33.33%) |

1.33 (0.49- 3.60) |

0.5705 |

5 (-37.50%) |

0.63 (0.22- 1.80) |

0.3832 |

10 (+100.00%) |

2.00 (0.73- 5.49) |

0.1786 |

5 (-50.00%) |

0.50 (0.18- 1.37) |

0.1786 |

10 (+100.00%) |

2.00 (0.73- 5.49) |

0.1786 |

14 (+40.00%) |

1.40 (0.68- 2.89) |

0.3632 |

|

Conservative Management |

9 |

11 (+22.22%) |

1.22 (0.55- 2.71) |

0.6213 |

10 (-9.09%) |

0.91 (0.42- 1.96) |

0.808 |

7 (-30.00%) |

0.70 (0.29- 1.70) |

0.4318 |

3 (-57.14%) |

0.43 (0.12- 1.57) |

0.201 |

6 (+100.00%) |

2.00 (0.53- 7.59) |

0.3083 |

8 (+33.33%) |

1.33 (0.50- 3.58) |

0.5686 |

Each RR (95% CI) and p-value compares the given year to the year prior. Bold p-values are statistically significant Abbreviations: RR = Relative Risk; CI = Confidence Interval.

DISCUSSION

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to analyze the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dog bite injuries, and, more specifically, injuries to the head, neck, or face. Across all cohorts, the incidence of dog bite injuries increased until 2020, when there was a decrease in the number of bites and injuries. The database cohorts showed a rebound that surpassed pre-pandemic levels. However, once looking at patients specifically with facial injuries at our institution, the post-pandemic increase did not reach the pre-pandemic levels. Patients between the ages of 0 and 9 years old were most often afflicted by dog bites, though the number of adult patients bitten significantly increased post-pandemic. There was a slight female predominance in all cohorts. At our institution, the cheeks, lips, and nose were the facial structures most frequently bitten by a dog. Patients evaluated at our institution that did not require hospital admission decreased in 2020. The number of bedside repairs performed at our institution in 2020 also decreased, followed by increases in 2021 and 2022. Interestingly, March-August of 2023 had the highest volume of patients requiring surgical repair of their facial dog bite injuries at our institution.

The incidence of dog bite injuries in all cohorts increased from 2017-2019. This was followed by a decrease in 2020 and a post-pandemic rebound that reached, and sometimes surpassed, pre-pandemic levels. One potential reason for this trend is an increase in dog ownership. According to the American Veterinary Association, dog ownership has grown more than 40% over the past 3 decades [6]. Additionally, data from the Center for Disease Control demonstrates that dog bites to the face doubled from 2018 to 2021 along with an increase in overall dog bite associated injuries [7]. The continued increase in injuries post-pandemic could be explained by the above data and the higher rates of aggressive behaviors in “pandemic puppies [4].

Patients in the 0- to 4-year-old and 5- to 9-year-old groups consistently had the highest incidence of dog bite injuries across all four cohorts within the current study. This finding supports multiple previously published studies that show a higher incidence of dog bite injuries in children than adults, especially for injuries to the head, neck, or face [5-17]. Moreover, a systematic review of pediatric dog bites shows that children under the age of nine years had the highest burden of dog bite injuries compared to older children [18]. Therefore, there is opportunity for collaboration between the veterinary and medical communities and outreach to provide education to dog owners and patients on interactions between dogs and humans to reduce the incidence of dog bite injuries, especially within the pediatric patient population.

Though children are most often afflicted, our data suggest the pandemic changed the rates in which adults were bitten by a dog. Most age groups had a decrease in the number of patients and injuries in 2020. During the height of the pandemic, the mean patient age at our institution during March-August 2020 was 21.8 years, which was significantly higher than the mean age in 2019. This may be attributed to the government-imposed restrictions including shelter-in-place orders and travel advisories [19]. If patients were staying at home in 2020, there were fewer instances to interact with, and possibly be bitten by, dogs outside of the household. However, more adults at home with their dogs rather than in the workplace may be associated with the increase in mean age seen at our institution. Once the government restrictions were lifted past August 2020, there was a substantial increase in the number of adults seeking evaluation for dog bites. Because of the restrictions keeping humans and dogs at home, socialization was hindered. Socializing dogs leads to decreased aggressive and fearful behaviors [4-20]. Additionally, recent studies have shown that people of all ages have experienced alterations in their social habits and behaviors as a result of the pandemic [21-23]. Given this information, one can postulate that the social restrictions of the pandemic stunting socialization of both humans and dogs can contribute to this uptick in dog bite injuries that has continued to increase since the pandemic.

Female patients accounted for a slight majority of dog bites in all four cohorts in our study. This contrasts previously published literature that largely shows a male predominance in dog bite injuries [24-30]. A few studies do describe a slight female majority [31,32] or an even gender divide of patients evaluated for dog bite injuries [33].

Results from our institutional cohort show that the cheeks, lips, and nose are the most frequently bitten anatomic structures on the face. These findings are consistent with previously published literature, and this is especially prevalent in pediatric patient populations [5-34]. One study notes that the face is the third most commonly location bitten by a dog, following the upper and lower extremities [34]. Given the shorter stature of children and therefore proximity of their faces to a dog’s mouth, one can see how children were most often to experience dog bites to facial structures.

At our institution, in 2020, there was a significant decrease in the number of patients evaluated that were not admitted to the hospital, though there was no significant change in the total number of patients admitted. There was also a decrease in the number of patients requiring bedside repair of facial dog bite injuries. This could be related to patients delaying or avoiding medical care for less severe injuries as a result of the pandemic. One study found that 79% of patients postponed medical care within 2020 due to fears around contracting the novel coronavirus [35]. Alternatively, the social distancing practiced during much of 2020 could have prevented people from interacting with dogs, leading to a temporary decrease in the incidence of less severe dog bites that were amenable to bedside repairs but a similar rate from the pre-pandemic period of patients requiring admission for more severe dog bite injuries. Despite this transient decrease, 2021 and 2022 reported significant increases in the numbers of bedside repairs performed. This may be attributed to the resocialization of humans and dogs after previous restrictions were lifted, as literature suggests that lockdown a had lasting impact on how both humans and dogs socialize [4-23].

Post-pandemic at our institution, there was a continued trend toward increased operative repairs during the March-August months with the highest number seen in the year 2023 (24.24%). However, the overall year-to-year difference was not significant. Existing literature reports a higher incidence of dog bites in summer months [36,37]. One study found an increase in aggression displayed by dogs adopted during the pandemic [4]. This may have contributed to the increased in operative dog bite cases.

While our study provides trends in dog bite injuries before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to acknowledge limitations. First, the data within the study relies on electronic medical records from a single institution and the TriNetX Research Network, providing potential biases and limitations inherent to any retrospective or database study [38]. Additionally, TriNetX captures data from large HCOs utilizing ICD-10 and procedure codes, meaning that smaller and private practices are not included in the data, making the data less generalizable. Similarly, the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center is a level 1 trauma center, meaning that higher acuity injuries may present to our hospital compared to community hospitals or clinics. Nonetheless, our study captured millions of patients bitten by dogs across the United States, contributing valuable insight into the landscape of dog bite-induced injuries and subsequent patient needs. Further research across multiple organizations can provide more generalizable data for dog bite injuries specifically to the head, neck, or face.

CONCLUSION

After a few years of steady increases, facial injuries due to dog bites showed the expected decrease during the pandemic. There was a subsequent increase in post-pandemic dog bites that reached, and sometimes surpassed, pre-pandemic levels. Though children tended to experience more dog bite injuries than adults, the rates of these injuries occurring to adults also increased post pandemic. Further research on a larger scale is warranted to identify specific factors associated with this increase in order to target preventative education and interventions.

Ethical Approval

The Pennsylvania State College of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed and approved the study (Study ID# 24260).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Caia Hypatia for their support in manuscript preparation and submission.

REFERENCES

- Torales J, O’Higgins M, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020; 66: 317-320.

- Siettou C. Societal interest in puppies and the Covid-19 pandemic: A google trends analysis. Prev Vet Med. 2021; 196: 105496.

- Seksel K. Puppy socialization classes. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1997; 27: 465-477.

- Sacchettino L, Gatta C, Chirico A, Avallone L, Napolitano F, d’AngeloD. Puppies Raised during the COVID-19 Lockdown Showed Fearful and Aggressive Behaviors in Adulthood: An Italian Survey. Vet Sci. 2023; 10: 198.

- Topaloglu U, Palchuk MB. Using a Federated Network of Real-World Data to Optimize Clinical Trials Operations. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2018; 2: 1-10.

- Larkin M. Pet population continues to increase while pet spending declines. American Veterinary Medical Association. 2024.

- QuickStats: Number of Deaths Resulting from Being Bitten or Struck by a Dog,* by Sex - National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2011-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023; 72: 999.

- Hurst PJ, Hoon Hwang MJ, Dodson TB, Dillon JK. Children Have an Increased Risk of Periorbital Dog Bite Injuries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020; 78: 91-100.

- Weiss HB, Friedman DI, Coben JH. Incidence of dog bite injuries treated in emergency departments. JAMA. 1998; 279: 51-53.

- Gandhi RR, Liebman MA, Stafford BL, Stafford PW. Dog bite injuries in children: a preliminary survey. Am Surg. 1999; 65: 863-864.

- Kaye AE, Belz JM, Kirschner RE. Pediatric dog bite injuries: a 5-year review of the experience at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009; 124: 551-558.

- Ellis R, Ellis C. Dog and cat bites. Am Fam Physician. 2014; 90: 239- 243.

- Ting JW, Yue BY, Tang HH, Rizzitelli A, Shayan R, Raiola F, et al. Emergency department presentations with mammalian bite injuries: risk factors for admission and surgery. Med J Aust. 2016; 204: 114. e1-114.e7.

- Rosado B, García-Belenguer S, León M, Palacio J. A comprehensive study of dog bites in Spain, 1995-2004. Vet J. 2009; 179: 383-391.

- Piccart F, Dormaar JT, Coropciuc R, Schoenaers J, Bila M, Politis C. Dog Bite Injuries in the Head and Neck Region: A 20-Year Review. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2019; 12: 199-204.

- Meek E, Lewis K, Hulbert J, Mustafa S. Who let the dogs out? A 10-year review of maxillofacial dog bite injuries. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2024; 62: 831-835.

- Islam S, Ansell M, Mellor TK, Hoffman GR. A prospective study into the demographics and treatment of paediatric facial lacerations. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006; 22: 797-802.

- Patterson KN, Horvath KZ, Minneci PC, Thakkar R, Wurster L, Noffsinger DL, et al. Pediatric dog bite injuries in the USA: a systematic review. World J Pediatr Surg. 2022; 5: e000281.

- Gostin LO, Wiley LF. Governmental Public Health Powers During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Stay-at-home Orders, Business Closures, and Travel Restrictions. JAMA. 2020; 323: 2137-2138.

- McEvoy V, Espinosa UB, Crump A, Arnott G. Canine Socialisation: A Narrative Systematic Review. Animals (Basel). 2022; 12: 2895.

- Doan SN, Burniston AB, Smiley P, Liu CH. COVID-19 Pandemic and Changes in Children’s Behavioral Problems: The Mediating Role of Maternal Depressive Symptoms. Children (Basel). 2023; 10: 977.

- Breaux R, Cash AR, Lewis J, Garcia KM, Dvorsky MR, Becker SP. Impacts of COVID-19 quarantine and isolation on adolescent social functioning. Curr Opin Psychol. 2023; 52: 101613.

- Finlay J, Meltzer G, O’Shea B, Kobayashi L. Altered place engagementsince COVID-19: A multi-method study of community participation and health among older americans. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2024; 6: 100184.

- Boyd LC, Chang J, Ajmera S, Wallace RD, Alvarez SM, Konofaos P. Pediatric Dog Bites: A Review of 1422 Cases Treated at a Level One Regional Pediatric Trauma Center. J Craniofac Surg. 2022; 33: 1118- 1121.

- Westgarth C, Brooke M, Christley RM. How many people have been bitten by dogs? A cross-sectional survey of prevalence, incidence and factors associated with dog bites in a UK community. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2018; 72: 331-336.

- Georges K, Adesiyun A. An investigation into the prevalence of dog bites to primary school children in Trinidad. BMC Public Health. 2008; 8: 85.

- Shuler CM, DeBess EE, Lapidus JA, Hedberg K. Canine and human factors related to dog bite injuries. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008; 232: 542-546.

- Beck AM, Jones BA. Unreported dog bites in children. Public Health Rep. 1985; 100: 315-321.

- Rocha JLFDN, Leão CCA, Canedo LR, Macedo LFR, Rosa SC, Macedo JLS. Epidemiological Profile of Victim Patients of Facial Canine and Human Bites in a Public Hospital. J Craniofac Surg. 2024; 35: 618-621.

- Román J, Willat G, Piaggio J, Correa MT, Damián JP. Epidemiology of dog bites to people in Uruguay (2010-2020). Vet Med Sci. 2023; 9: 2032-2037.

- Khan K, Horswell BB, Samanta D. Dog-Bite Injuries to the Craniofacial Region: An Epidemiologic and Pattern-of-Injury Review at a Level 1 Trauma Center. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020; 78: 401-413.

- Mattice T, Schnaith A, Ortega HW, Segura B, Kaila R, Amoni I, et al. A Pediatric Level III Trauma Center Experience With Dog Bite Injuries. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2024; 63: 914-920.

- Hazel SJ, Iankov I. A public health campaign to increase awareness of the risk of dog bites in South Australia. Prev Vet Med. 2024; 231: 106298.

- Ali SS, Ali SS. Dog bite injuries to the face: A narrative review of the literature. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022; 8: 239- 244.

- Anderson KE, McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Barry CL. Reports of Forgone Medical Care Among US Adults During the Initial Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021; 4: e2034882.

- Monroy A, Behar P, Nagy M, Poje C, Pizzuto M, Brodsky L. Head and neck dog bites in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009; 140: 354-357.

- Frangakis CE, Petridou E. Modelling risk factors for injuries from dog bites in Greece: a case-only design and analysis. Accid Anal Prev. 2003; 35: 435-438.

- Haut ER, Pronovost PJ, Schneider EB. Limitations of administrative databases. JAMA. 2012; 307: 2589-2590.