Parapharyngeal Schwannoma of the Hypoglossal Nerve in a 7-Year Old Girl: A Rare Case

- 1. Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, University Hospital Ibn Rochd, Morocco

Abstract

Schwannomas are benign tumors originating from Schwann cells of peripheral nerves. While common in adults, they are rare in children and even more so when involving cranial nerves.

INTRODUCTION

Schwannomas are benign tumors originating from Schwann cells of peripheral nerves. While common in adults, they are rare in children and even more so when involving cranial nerves. Among these, hypoglossal nerve schwannomas are extremely uncommon, typically presenting as slow-growing, painless masses. We report the case of a parapharyngeal schwannoma originating from the hypoglossal nerve in a 7-year-old girl, emphasizing the diagnostic and surgical challenges, particularly the functional impact of nerve sacrifice.

CASE PRESENTATION

Clinical History

• Patient: A 7-year-old girl with no previous medical history.

• Chief Complaint: Right cervical mass evolving over 7 months.

• Clinical Examination

o Firm, immobile, non-tender mass approximately 5 cm in diameter, located under the right mandibular angle.

o Protrusion into the lateral oropharyngeal wall.

o No signs of inflammation or other abnormalities.

o Normal tongue movements on initial examination.

Investigations

Imaging Findings:

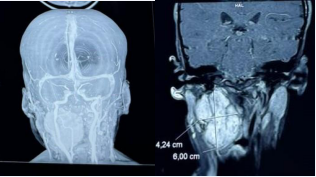

1. Cervical CT Scan

o Parapharyngeal pre-styloid lesion measuring 55 × 34 mm.

o Displacement of the ipsilateral jugulocarotid axis.

o Bulging into the oropharynx, with a probable origin from the hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII).

2. Angio-CT of Supra-Aortic Vessels

o Exclusion of vascular involvement. o Mass displaced the carotid artery laterally without significant compression (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Axial CT scan showing the parapharyngeal mass.

Surgical Findings and Procedure

The patient underwent surgical excision of the mass via a right cervicotomy. Intraoperative exploration revealed a well-encapsulated lesion originating from the hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII). The tumor measured approximately 55×34 mm and was located in the prestyloid parapharyngeal space, displacing the oropharyngeal wall and the ipsilateral jugulocarotid axis. During the procedure, the tumor was found to involve the external carotid artery and a segment of the hypoglossal nerve.

To achieve complete tumor excision, the involved portion of the external carotid artery was ligated and resected, as preoperative angioscans had confirmed adequate collateral circulation.

Additionally, a portion of the hypoglossal nerve directly invaded by the tumor was sacrificed. To preserve functional outcomes, a direct nerve repair was performed intraoperatively as follows:

Schwannomas, neurofibromas, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors.

1. Segmental Resection of the Nerve: The tumorinvaded segment of the hypoglossal nerve was excised, ensuring clear margins.

2. Microsurgical Repair: The proximal and distal nerve stumps were approximated using fine non-absorbable sutures (8-0) under a surgical microscope. Direct end-to-end anastomosis was achieved without excessive tension.

3. Postoperative Outcome: Postoperatively, the patient developed right-sided tongue paralysis, consistent with the hypoglossal nerve sacrifice. Speech therapy and swallowing rehabilitation were initiated (Figure 2). Histopathological Results: Histopathological analysis confirmed a schwannoma.

Figure 2: Angiographic reconstruction showing vascular displacement by the mass.

DISCUSSION

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Schwannomas are benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors that arise from Schwann cells. They are rare in children and even more so when involving cranial nerves.Hypoglossal nerve schwannomas account for less than 5% of all head and neck schwannomas, making them an exceptional finding in pediatric populations [1,2]. Most patients with hypoglossal schwannomas present in adulthood, and childhood cases are exceedingly rare.

The hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII) controls the movements of the tongue, and its schwannomas typically originate in the intracranial or parapharyngeal region. Tumor growth leads to compression of adjacent structures, and depending on the tumor’s location, symptoms may range from painless cervical masses to hypoglossal nerve palsy characterized by ipsilateral tongue weakness and atrophy.

Clinical Presentation

In this case, the absence of initial tongue paralysis despite the tumor’s origin in the hypoglossal nerve highlights the slow and compressive growth pattern typical of schwannomas. Asymptomatic presentation is common in early stages, particularly for extracranial schwannomas. However, advanced cases may present with signs of nerve dysfunction, including dysarthria, dysphagia, or visible tongue atrophy [3,4].

Differential diagnoses for parapharyngeal masses in children include:

• Neurogenic tumors: Schwannomas, neurofibromas, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors.

• Vascular lesions: Paragangliomas or hemangiomas.

• Congenital anomalies: Branchial cleft cysts or lymphangiomas.

• Malignant lesions:Lymphomas or rhabdomyosarcomas.

Imaging modalities like CT and MRI are essential to narrow the differential diagnosis. MRI, in particular, provides superior soft-tissue contrast and can reveal characteristic features of schwannomas, such as a target sign or cystic degeneration [5].

Surgical Considerations

Complete surgical resection remains the cornerstone of treatment for schwannomas, as they are radioresistant. In this case, tumor involvement of the hypoglossal nerve necessitated nerve sacrifice to achieve clear margins and minimize the risk of recurrence.

The surgical approach to parapharyngeal tumors depends on their location and extent. A cervicotomy offers direct access while preserving critical vascular and neural structures. However, for hypoglossal nerve schwannomas, the functional implications of nerve resection are significant. Postoperative deficits include ipsilateral tongue paralysis, deviation of the tongue toward the affected side, and difficulties in speech and swallowing [6,7].

Rehabilitation and Functional Outcomes

Rehabilitation plays a pivotal role in optimizing outcomes after hypoglossal nerve resection. Speech and swallowing therapy can significantly mitigate functional impairments, especially in pediatric patients with high neuroplasticity [8]. Surgical techniques such as hypoglossal nerve repair or grafting have been described in some cases, although their success depends on the extent of nerve damage and tumor size [9].

Unique Aspects of this Case

This case is notable for the following reasons:

1. Age of the patient: Hypoglossal schwannomas are exceedingly rare in children.

2. Imaging discrepancies: Initial imaging suggested a vascular lesion, underscoring the importance of histopathological confirmation.

3. Functional preservation preoperatively: Despite tumor involvement, the patient retained normal tongue function initially.

4. Postoperative management: Comprehensive rehabilitation was initiated early to address functional deficits (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Intraoperative view of the encapsulated schwannoma originating from the hypoglossal nerve.

Review of Literature

A literature review highlights similar cases:

• Huang et al., reported hypoglossal schwannomas presenting as parapharyngeal masses in adults, emphasizing imaging and surgical approaches [3].

• Riffaud et al., reviewed hypoglossal schwannomas, noting that extracranial tumors often present with late-stage nerve deficits [4].

• A recent study by Liao et al., detailed pediatric schwannomas, stressing the rarity and challenges of managing cranial nerve involvement [10].

CONCLUSION

Hypoglossal nerve schwannomas are rare entities, particularly in children, and require a high index of suspicion for diagnosis. Imaging plays a critical role, but definitive diagnosis is achieved through histopathology. Surgical excision remains the treatment of choice, but it often necessitates cranial nerve sacrifice, with significant postoperative functional implications. Early and tailored rehabilitation can improve outcomes, particularly in pediatric patients.

REFERENCES

1. Wenig BM. Atlas of Head and Neck Pathology. 3rd ed Elsevier. 2016.

4. Riffaud L. “Schwannomas of the hypoglossal nerve.” J Neurosurg. 2003; 98: 1273-1278.

5. Som PM, Curtin HD. Head and Neck Imaging. 5th ed Mosby. 2011.

6. Saito DM. Management of parapharyngeal space tumors. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 2015; 48: 121-130.

7. Colbert SD, Khaldi A, Touati S, Gritli S. Surgical approaches to parapharyngeal space schwannomas. Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 2012; 50: 771-775.

8. D’Souza M. Postoperative rehabilitation in cranial nerve injuries. J Rehabilitation Med. 2018; 50: 785-792.

9. Davis ME. Nerve grafting techniques after cranial nerve tumor excision. World Neurosurg. 2021; 151: e21-e29.

10. Liao C. Schwannomas in pediatric patients: Clinical characteristics and management. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2022; 57: 150-157.