Rethinking Lower Lip Weakness after Face and Neck Lift

- 1. Department of Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery, Division of Facial Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, USA

Abstract

Face and neck lifts are widely utilized procedures in facial rejuvenation. Facial weakness remains one of the most feared complications, and transient lower lip weakness remains the most common weakness seen after these procedures. In the past, lower lip paresis was regarded as stemming from marginal mandibular nerve weakness. However, recent intraoperative studies using distal facial nerve branch electric stimulation have demonstrated that the cervical branches of the facial nerve provide the primary innervation of the depressor labii inferioris muscle; and injury to these branches may result in lower lip weakness. Therefore, understanding the anatomy of these cervical branches, and how to preserve them during face and neck lifts, is critical to limit post-operative facial paresis. This paper describes our current understanding of depressor labii inferioris innervation, its relevance to face and neck lift procedures, and strategies to prevent and manage inadvertent injury to the cervical branches of the facial nerve.

Keywords

• Facelift

• Neck Lift

• Facial Weakness

• Facial Nerve

Citation

Mowery A, Li ML (2025) Rethinking Lower Lip Weakness after Face and Neck Lift. Ann Otolaryngol Rhinol 12(5): 1370.

ABBREVIATIONS

CBFN: Cervical Branches of Facial Nerve; DAO: Depressor Anguli Oris; Depressor Labii Inferioris; SMAS: Superficial Muscular Aponeurotic System.

INTRODUCTION: RETHINKING LOWER LIP WEAKNESS AFTER FACE AND NECK LIFT

Face and neck lifts are increasingly popular and highly effective procedures for facial rejuvenation, designed to restore youthful contours by repositioning and resuspending facial tissues. As techniques have evolved toward deeper plane dissections and extended rejuvenation of the face and neck, the dissection often approaches the facial nerve and its branches more closely, allowing for potentially greater aesthetic benefit but also introducing risk. Although overall complication rates remain low, postoperative facial weakness – ranging from transient paresis to permanent paralysis – remains one of the most feared complications, given its functional and emotional impact on patients. Transient weakness is far more common than long-term paralysis.

Prior studies reported incidence of temporary injury in the 0.4 to 2.6% range and permanent injury in around 0.1%, and a recent meta-analysis estimates the rate of self-limited paresis to be 0.7% and long-term paralysis to be 0.05% [1-3]. Weakness most commonly involves one facial nerve branch. The most frequently affected branches are marginal mandibular and temporal branches, though multiple branches can be affected [4].

When a patient develops an asymmetric lower lip, we typically attribute this to the marginal mandibular nerve. In these cases, the lower lip that is weak does not move downwards symmetrically with the opposite side which leads to elevation of the weak lip and asymmetry during speech and smile. As we refine our understanding of facial nerve innervation of the facial muscles, it has become increasingly clear that what we have previously classified as marginal mandibular nerve weakness is more commonly due to cervical branch weakness [5,6]. Injury to the cervical branch of the facial nerve (CBFN) may be overlooked as an etiology of lower face weakness [1,7]. This paper aims to provide a discussion of recent advances in our understanding of the role of the CBFN in lower lip weakness after face and neck lift procedures.

Over the last decade, there has been significant evolution in practice patterns of surgical techniques employed for face and neck rejuvenation coupled with improved understanding of facial nerve anatomy and physiology driven in part by increased use of intraoperative electric stimulation, particularly for facial nerve surgeries and facial rejuvenation procedures. For facial rejuvenation, there has been increasing popularity in approaches that involve significant dissection below the superficial muscular aponeurotic system (SMAS) layer and further forward in the face with more exposure to the more distal facial nerve branches than before. These techniques have seen increased interest, with deep submental neck contouring procedures including post-platysma fat resection, submandibular gland reduction, and digastric muscle reductions becoming more popular in recent years. In these dissections, the facial nerve branches are closer to the plane of dissection [8]. Studies on the rate of facial weakness between sub-SMAS and more superficial techniques have had mixed results regarding the impact of the dissection on facial nerve weakness: one recent meta-analysis found no difference between superficial and deep approaches to face lifting [9]. However, a systematic review of neck lifts did find several papers that reported a higher rate of nerve weakness in deep plane techniques – the rate of temporary or permanent nerve weakness varied by technique used (from 0.2% to 10%, compared to 1% in non-deep plane techniques), but was particularly elevated in patients with submandibular gland resection or digastric muscle manipulation [10]. A systematic review of cosmetic submandibular gland reduction that included studies totaling 602 patients found lower lip weakness in 4.7% of patients post-operatively, and a series of 504 patients undergoing subplatysmal neck lift found that 5.7% of patients experienced lower lip depressor weakness [11,12]. Some of this increased risk may be reduced by better understanding of surgical anatomy, the innervation patterns of lower facial muscles, and improvement in surgical techniques.

FACIAL NERVE ANATOMY

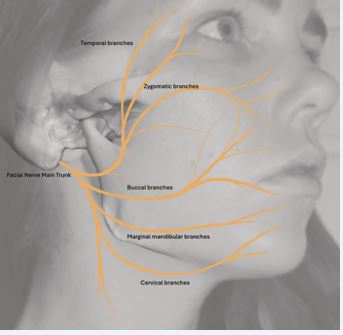

To minimize facial weakness post-facelift, it is crucial to understand the relevant facial nerve anatomy. After traversing the mastoid bone, the facial nerve courses through the stylomastoid foramen and enters the parotid gland dividing the superficial and deep lobes. Within the parotid gland the facial nerve diverges, forming upper and lower divisions and interconnecting branches. Distally, branches are conventionally categorized as temporal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical. The middle branches – zygomatic and buccal – have a greater degree of redundancy and inter-branching than the superior-most and inferior-most branches [13]. The peripheral facial nerve branches innervate the muscles of facial expression; all are innervated on their deep surface except for the buccinator, mentalis, and levator anguli oris, which are innervated on their superficial surface [14]. When dissecting in a sub-SMAS plane, the facial nerve branches will be seen deep to the area of dissection. The facial nerve branches are the thickest and most robust laterally and become progressively thinner as we proceed anteriorly in the face. Facial nerve anatomy is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Facial nerve branch anatomy; note the distal branches of the cervical branches of the facial nerve that ascend medially to innervate the depressor labii inferioris.

LOWER LIP INNERVATION

Historically, our understanding of facial muscle innervation by the facial nerve was based largely on cadaveric studies, where researchers would follow facial nerve branches to see what they innervated. Such studies were limited by not being able to observe nerve stimulation and involved inherent uncertainty. With the advent of electric nerve stimulation devices used intra operatively, we are now able to directly observe the effects of stimulating facial nerve branches. There has also been increased use of facial neurectomy procedures in patients with synkinesis after facial paralysis; these procedures involve a deep plane facial dissection to find and stimulate facial nerve branches. These procedures have provided valuable insight into facial muscle innervation and revealed some surprising findings that are contrary to prior beliefs.

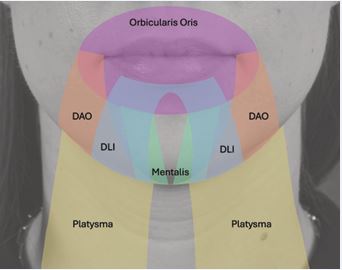

Figure 2 Illustration of peri-oral musculature; orbicularis, depressor anguli oris (DAO), depressor labii inferioris (DLI), mentalis, and platysma.

Important lower lip muscles are shown in Figure 2; they include the depressor angulioris (DAO), which provides a diagonal downward pull at the oral commissure; the depressor labii inferioris (DLI), which contributes to a downward and lateral pull along the length of the lower lip, as the DLI muscles on each side interdigitate at midline and function as a sling across the lower lip; and the mentalis, which elevates and protrudes the lower lip. The marginal mandibular nerve has been long viewed as providing the primary innervation of the lower lip. It supplies the DAO and mentalis muscles. Traditionally, it was thought that the DLI was innervated primarily – or solely – by the marginal mandibular nerve [15]. The CBFN was not thought to contribute significantly to muscles of facial expression, and was thought to be innervate the platysma exclusively. However, DLI weakness has been seen after face and neck lift surgery when the marginal mandibular nerve was preserved, which raised the question: are we inaccurate in our thinking that the DLI is innervated by the marginal mandibular nerve? [16].

With that in mind, a 2023 study of distal facial nerve dissection and branch stimulation, performed in vivo in patients undergoing selective neurectomy, found that the DLI is innervated by nerve branches originating from the CBFN [17]. This study reported that in 59 of their 60 cases, the DLI was innervated by a nerve from the CBFN, arising about 2cm below the mandibular border and distinct from the marginal mandibular branches; this nerve branched distally into two distinct branches in 81% of cases. A prospective facial nerve dissection and stimulation study of 20 patients (again, patients undergoing selective neurectomy) published in 2025 describes innervation of the DLI as two separate components: the lateral DLI relatively weakly innervated by a superficial branch of the marginal mandibular nerve, and stronger innervation to the medial DLI by a distal branch of the CBFN [16]. So, it appears the conventional thinking that the marginal mandibular nerve innervates the DLI is flawed, and that a much greater component of innervation is from the CBFN, which has implications for surgical strategies to avoid causing facial paresis.

Several recent cadaveric anatomic studies have described the course of the CBFN: it travels just deep to the investing layer of the deep cervical fascia as it exits the parotid gland, runs in this deep fascia for several centimeters, then penetrates the investing layer and continues in the areolar fascia just deep to the platysma before eventually entering the platysma, which it innervates [6,18,19]. It follows a course between the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the mandible, superior to the level of the hyoid [6]. It bifurcates 90% of the time into ascending and descending branches in a region between the vertical planes of the gonion and the facial notch [6]. The CBFN point of emergence, where it transitions from the investing layer of the deep cervical fascia to follow a more superficial trajectory immediately subplatysmal, is described as occurring in the distal third of a line extending between a point on the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle 5cm below the mandibular angle and the facial notch [18,19]. As the CBFN courses medially, it runs close to the submandibular gland capsule [6].

AVOIDING INJURY TO THE CERVICAL BRANCH OF THE FACIAL NERVE DURING FACE AND NECK LIFT

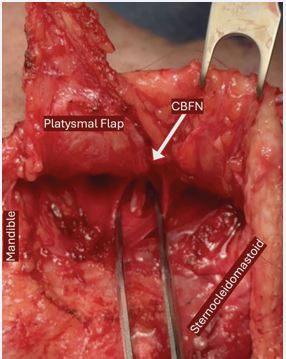

There are a number of strategies one might employ to improve preservation of the CBFN during face and neck lift procedures. Consider not using lidocaine and rather use plan epinephrine for local vasoconstriction to avoid decreasing nerve responsiveness during surgery. Plan to use a nerve stimulator for intraoperative feedback and keep vigilant attention to possible nerve branches when dissecting in close proximity to the anticipated location of nerves.Using our knowledge of CBFN anatomy, we can anticipate safe zones of dissection to avoid injury to the CBFN. An intra-operative photograph is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Cervical branches of facial nerve (CBFN) visible in the subplatysmal plane during a neck lift procedure.

to illustrate the CBFN seen in the subplatysmal dissection during a neck lift. In the neck, when one is posterior to the location where the CBFN penetrates through the deep cervical fascia, the CBFN is at low risk of injury. However, once dissection extends approximately 1.5 cm anterior to the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM), and particularly within the superior 2 cm beneath the mandibular border, increased caution is warranted. In these regions, subplatysmal dissection should proceed more slowly and deliberately. Meticulous technique is essential – care must be taken not to confuse retaining ligaments or adhesions between the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the platysma with nerve branches, and it is important to recognize that cervical branches may be multiple and are often densely adherent to the deep surface of the platysma [18].

On the medial, submental dissection, if one extends the subplatysmal fat dissection too far laterally, it is also possible to injure the distal branches of the CBFN [19]. Beyond extent of dissection, it is also recommended that one employ blunt dissection only when elevating in the subplatysmal plane below the mandibular angle; vertical spreading motions to avoid inadvertent injury to the CBFN are advisable [6,7,16]. During submandibular gland reduction, one should be mindful that the CBFN may lie in close proximity to the gland capsule, and limit use of heat energy devices that could cause a thermal injury to the nerve [6,16,19].

ADDRESSING DEPRESSOR LABII INFERIORIS WEAKNESS POST-OPERATIVELY

If injury to the CBFN or post-operative DLI weakness does occur, then one should first be reassured that the vast majority of instances of lower face weakness after face or neck lift do recover with time, typically within about 3 months [5,7,20]. Therefore, watchful waiting for nerve recovery is a reasonable strategy [7]. To treat bothersome facial asymmetry while waiting for recovery, one can consider neurotoxin injection into the contralateral, unaffected, DLI to create a more even smile [3,4]. One may also consider referral to physical therapy; this may assist with strategies for facial expression retraining, and neuromuscular education once nerve recovery begins [3,21]. If DLI recovery is not complete, then there are further options to discuss with patients, depending on their individual goals. Continued serial neurotoxin administration is certainly possible, particularly during the first year, but there are surgical options to consider as well. Selective facial neurectomy of contralateral CBFN branches or selective facial myectomy of the contralateral DLI are both potential strategies to improve facial symmetry. Referral to a facial nerve specialist who can provide appropriately comprehensive counseling regarding these options is advisable. Recreating the vector of DLI pull on the lower lip with a static reconstruction using fascia lata is another consideration. However, in our practice, we generally recommend selective neurectomy or myectomy prior to proceeding with static reconstruction, as these dynamic procedures may achieve satisfactory balance without the need for additional grafting.

CONCLUSIONS

Facial weakness following face and neck lift procedures is a dreaded complication, and lower lip weakness post operatively is not entirely uncommon. Historically this was attributed largely to inadvertent injury to the marginal mandibular nerve, but new studies suggest that the role of the CBFN in innervating the DLI has been underappreciated, and CBFN injuries deserve greater attention. The CBFN follows a deep course between the sternocleidomastoid muscle and mandibular angle but becomes superficial as it moves anteriorly under the platysma, within 2cm below the mandible. Therefore, careful, blunt dissection should be employed when in the subplatysmal plane below the mandible. If DLI paresis does occur post-operatively, then it is likely to recover, but one may temporarily improve symmetry with contralateral DLI neurotoxin administration. If there is permanent DLI paralysis, one can consider surgical options including selective facial neurectomy or myectomy of the contralateral side, or static reconstruction of the affected side.

REFERENCES

- Gandra G, Silva BS, Horta R. Facelift Surgery and Nerve Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2025; 49: 5696-5711.

- Bloom JD, Immerman SB, Rosenberg DB. Face-lift complications. Facial Plast Surg. 2012; 28: 260-272.

- Goldberg TK, McGonagle ER, Hadlock TA. Post–face lift facial paralysis: a 20-year experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024; 154: 748- 758.

- Azizzadeh B, Mashkevich G. Nerve injuries and treatment in facial cosmetic surgery. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2009; 21: 23- 29.

- Daane SP, Owsley JQ. Incidence of cervical branch injury with “marginal mandibular nerve pseudo-paralysis” in patients undergoing face lift. Plast reconstr surg. 2003; 111: 2414-2418.

- Cakmak O, Buyuklu F, Kaya KS, Babakurban ST, Bogari A, Tunal? S. Anatomical Insights on the Cervical Nerve for Contemporary Face and Neck Lifting: A Cadaveric Study. Aesthet Surg J. 2024; 44: NP532- NP539.

- Azizzadeh B, Lu RJ. Facial Nerve Considerations for the Deep Plane Facelift and Neck Lift. Facial Plast Surg. 2024; 40: 687-693.

- Luu NN, Friedman O. Facelift surgery: history, anatomy, and recent innovations. Facial Plast Surg. 2021; 37: 556-563.

- Chinta SR, Brydges HT, Laspro M, Shah AR, Cohen J, Ceradini DJ. Current trends in deep plane neck lifting: a systematic review. Ann Plast Surg. 2024; 94: 222-228.

- Vayalapra S, Guerero DN, Sandhu V, Happy AA, Imantalab D, Kissoonsingh P, et al. Comparing the Safety and Efficacy of Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System and Deep Plane Facelift Techniques: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Plast Surg. 2025; 95: 582- 589.

- Benslimane F, Kleidona IA, Cintra HPL, Ghanem AM. Partial removal of the submaxillary gland for aesthetic indications: a systematic review and critical analysis of the evidence. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2020; 44: 339-348.

- Auersvald A, Auersvald LA, Oscar Uebel C. Subplatysmal necklift: a retrospective analysis of 504 patients. Aesthet Surg J. 2017; 37: 1-11.

- Gataa IS, Faris BJM. Patterns and surgical significance of facial nerve branching within the parotid gland in 43 cases. Oral maxillofac surg. 2016; 20: 161-165.

- Marur T, Tuna Y, Demirci S. Facial anatomy. Clin Dermatol. 2014; 32: 14-23.

- Tzafetta K, Terzis JK. Essays on the facial nerve: Part I. Microanatomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010; 125: 879-889.

- Frants A, Leader B, Lu RJ, Azizzadeh B. Dual innervation of the depressor labii inferioris and implications for deep plane facelift and structural neck contouring: Insights from in vivo stimulation of the facial nerve branches. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2025; 27: 402- 405.

- Kaufman-Goldberg T, Flynn JP, Banks CA, Varvares MA, Hadlock TA. Lower facial nerve nomenclature clarification: Cervical branch controls smile-associated lower lip depression and dental display. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023; 169: 837-842.

- Lindsey Jr JT, Lee JJ, Phan HTP, Lindsey Sr JT. Defining the cervical line in face-lift surgery: a three-dimensional study of the cervical and marginal mandibular branches of the facial nerve. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023; 152: 977-985.

- Minelli L, Wilson JL, Bravo FG, Hodgkinson DJ, O’Daniel TG, van der Lei B, et al. The functional anatomy and innervation of the platysma is segmental: implications for lower lip dysfunction, recurrent platysmal bands, and surgical rejuvenation. Aesthet Surg J. 2023; 43: 1091-1105.

- Owsley JQ, Agarwal CA. Safely navigating around the facial nerve in three dimensions. Clin Plast Surg. 2008; 35: 469-477.

- Oyer SL. Static lower facial reconstruction in facial paralysis. Oper Tech Otolayngol Head Neck Surg. 2021; 32: 219-225.