Sound Pressure Levels and use of Ear Protective Devices among Cement Factory Workers

- 1. Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Usmanu Danfodiyo Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

Abstract

Background: Occupational Noise exposure is a worldwide problem in industry and contributes 16% of hearing loss globally. Hearing protection devices

intended to reduce the incidence of noise-induced hearing loss are not efficiently used in many factories.

Aims and Objectives: To elucidate the sound pressure levels of the working environment in the cement company and to determine the prevalence of use of Hearing Protection Devices among these workers.

Method: A prospective cross sectional descriptive study of consenting workers at a cement company in Northwest Nigeria was conducted. A digital sound level meter well-calibrated TOMTOP class 2-model number H4320 with a range of 30-130 dB was used to measure the sound level in the morning, afternoon and evening, average of the readings was taken. A pretested interviewer administered questionnaire was used to assess the availability and use of Hearing protection Devices (HPD).

Results: Workers in the noise exposed sections were exposed to noise levels varying from 76dB in the mobile clinic to 104 dB in the power house and 40 dB in the central administration block which served as control. One hundred and eighty four (57.9%) of the study group used hearing protection devices of which only 62(33.7%) used it always.

Conclusion: The study revealed high intensity noise (mean ambient noise of 87.1dB-A) in the noise exposed sections. There was poor usage of hearing protection devices (57.9%).

Keywords

• Sound Pressure Levels; Hearing Protection Devices; Cement Workers; North Western Nigeria

Citation

Aliyu N, Iseh KR, Mohammed A, Shu’aibu L, Yikawe SS, et al. (2026) Sound Pressure Levels and use of Ear Protective Devices among Cement Factory Workers. Ann Otolaryngol Rhinol 13(1): 1383.

INTRODUCTION

Noise generation has risen in parallel with the industrial growth and technological advancements, and presently, many people in the world are exposed to intermittent or continuous sound levels greater than 85 dB(A) in their work environment [1]. Noise-induced hearing loss is a major occupational health hazard and is the second most reported occupational hazard in the United States of America (USA) [2]. At global scale, the major cause of noise-induced hearing loss in adults is occupational noise, which seems to be on the increase in developing countries [3]. Hearing impairment is gradual in onset but eventually destroys the hair cells of the organ of corti [4 6]. One-time exposure to high noise can cause acoustic trauma; however, repeated exposure to noise at various levels of loudness over an extended period leads to either reversible or permanent damage to the peripheral auditory end organs [7]. The reversible loss, typically referred to as a temporary threshold shift (TTS), results from exposure to moderately intense sound [8,9]. Occupational noise induced hearing loss is irreversible and incurable. Early detection and rehabilitation are highly recommended [10].

Generally, protective measures to deal with noise induced hearing loss are often inadequate [11]. In a study in Tanzania, it was found that hearing protection was not used by most of the noise-exposed factory workers [11]. A .similar study by Ahmad Ali et al on noise-induced hearing loss at a cement company in Northern Nigeria revealed a relatively low use of hearing protective devices by 64.5% but they have a program in place whereby older equipment, which is noisy, is being replaced by new ones [10]. For many occupations, this has been insufficient when the noise level exceeds 130-140dB. Occupational hearing loss is preventable through the use of engineering and administrative controls, hearing protection devices, and the monitoring of hearing with audiometric testing [12]. Substantial progress in the prevention of NIHL would be achieved through the verification of medical guidelines used in HCPs, and their adjustment to co-exposures in occupational settings, individual susceptibility factors, and specific needs of given workers [13]. This study aims to assess the noise levels, use of Hearing protection devices, and the Hearing thresholds of workers in a Cement factory in Northwestern Nigeria.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

This was a prospective, cross-sectional descriptive study conducted among workers in a Cement Factory in Northwestern Nigeria. The participants who fulfilled the criteria for the study and worked within the noisy areas were selected for the study. A control group matched for gender and age was selected from the non-noise-exposed area within the same industry. Participants were selected by a systematic sampling method, and the workers were serially numbered, and every even number was recruited for the study. The age range was 18 years and above. The nominal roll of the workers was obtained from the central administration with their full cooperation. Inclusion criteria were Participants aged 18 years and above, and those who gave consent to participate in the study. Those with a history of ear disease, exposure to ototoxic drugs, systemic illness, non-permanent staff, history of previous ear surgery, and those who did not give consent were excluded from the study.

Ethical approval was obtained from the research and ethic committee of the Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital and permission obtained from the management of the Cement Company plc was obtained. The study was explained to each participant in a simple and well-understood language, and written consent was obtained. An ear examination was done using a light source and a head mirror. Otoscopy was done using a Heine mini 2000 dry cell Otoscope.

Sound Level Meter (Noise Level Measurement)

Sound level meters determine sound pressure and are commonly used in noise pollution studies for the quantification of almost any noise, but particularly for industrial, environmental, and aircraft noise. A digital sound level meter, well-calibrated TOMTOP class 2 – Model Number H4320 with a range of 30 – 130 dB, was used to measure the sound level in the morning, afternoon, and evening. The sound meter was suspended by a tripod stand, one meter away from the machines. The readings were taken when the sound level meter became steady for at least 30 seconds. The average of the three readings was calculated.

Pure Tone Audiometry (PTA)

PTA is the universal gold standard subjective acoustic test used for clinical hearing assessment [14]. The study was conducted in the quietest room possible (37dB) within the central administration block after at least 14 hours of abstinence from noise, which allowed for recovery from temporary threshold shift. This might be less than optimal, but is still acceptable given a recent observation of the significant agreement between hearing threshold measured in a non-soundproof working environment and a soundproof proof booth [15]. The procedure was explained to the participants, using a headphone and a manual diagnostic pure-tone Audiometer (VMS Digi RS). A pure tone was sent into one of his ears while the other one was masked (masking was done for bone conduction using a narrow-band noise of 35dB). The procedure was similarly repeated in the other ear. The modified Hughson Westlake procedure was used to determine the hearing thresholds of participants. The Pure tone average was calculated at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000Hz and divided by 4 for each ear. The presence of a significant audiometric notch at 4 kHz was also considered. A 4 kHz notch was defined when the 4 kHz minus the 2 kHz threshold and the 4 kHz threshold minus the 8 kHz threshold were both > 10 dB. Hearing impairment was classified according to the World Health Organization classification 2014 [16].

RESULTS

A total of 318 subjects were recruited as study group (23 were excluded because of ear pathologies from 341), with equal number of controls. All participants were males in both groups. The study group had age range of 20-56 (mean of 37.4 ±8.85) years. Control group had age range of 20-58(mean of 37.5 ±9.31) years.

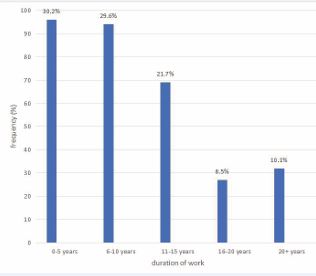

Duration of employment of workers

Figure 1 Shows the distribution of duration of employment (years) in the factory, with 30.2%, 29.6%, 21.7%, 8.5% and 10.1% respectively spending between 0-5, 6-10, 11-15, 16-20 and 21+ years in the factory/mill.

Figure 1 Duration of employment of workers in the noise exposed sections of factory/mill.

Noise exposure duration per day

Table 1 Shows daily work duration in hours with majority of workers 94.3% worked for 0-8 hours 5.7% worked for more than 8 hours daily.

Table 1: Duration of exposure in hours/day.

|

Daily work duration (hours) |

Frequency |

( % ) |

|

0-8 |

300 |

94.3 |

|

>8 |

18 |

5.7 |

|

Total |

318 |

100 |

Use of Hearing Protection Devices

Tables 2-4 shows the use of Hearing Protective Devices (HPD), the type they use, the frequency of using the devices and the reasons for not regularly using the devices or why they don’t use it at all.

Table 2: Use of Hearing protective Devices (HPD)

|

Use of Hearing Protective Device |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Yes |

184 |

57.9 |

|

No |

134 |

42.1 |

|

Total |

318 |

100.0 |

Table 3: Frequency of using Hearing Protection Devices

|

Frequency of using hearing protection device |

Frequency |

% |

|

Always |

62 |

33.7 |

|

Occasionally |

122 |

66.3 |

|

Total |

184 |

100.0 |

Table 4: Reasons for not using Hearing Protection Devices at all or reason for using it occasionally.

|

Reasons for not using hearing protective device. |

Frequency |

( %) |

|

Not available |

137 |

53.5 |

|

Not comfortable to use |

43 |

16.8 |

|

Not necessary |

74 |

28.9 |

|

Not aware |

2 |

0.8 |

|

Total |

256 |

100.0 |

Table 5: Prevalence of hearing loss in both ear

|

Prevalence of hearing loss |

Frequency (%) |

|

|

|

Subjects |

Control |

|

Normal hearing |

185 (58.2) |

273 (88.6) |

|

Unilateral |

48 (15.1) |

29 (9.4) |

|

Bilateral |

85 (27.6) |

16 (5.2) |

P=0.000

Table 6: Pure tone average and length of duration of employment.

|

Length (years) |

Right ear (dB) (+ SD) |

Left ear (dB) (+ SD) |

|

0-5 |

20.08 (+ 6.32) |

19.17 (+ 5.60) |

|

6-10 |

27.11 (+ 12.43) |

24.56 (+ 11.20) |

|

11-15 |

29.05 (+ 11.73) |

26.08 (+ 12.05) |

|

16-20 |

29.26 (+ 12.18) |

30.08 (+ 15.67) |

|

20+ |

23.65 (+ 9.03) |

24.93 (+ 12.80) |

P=0.000

factory, 42.7% in both ears. 15.1% affecting either of the ears and 27.6% both ears.

Correlation between mean pure-tone average (mPTA) and duration of employment

Table 6 highlights the relationship between Pure-tone average and length of duration of employment which was found to be statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Hearing loss due to continuous or intermittent noise exposure increases rapidly during the first 10-15 years of exposure, and the rate of hearing loss then decelerates as the hearing threshold increases [5-16]. In this study, it was observed that the highest prevalence of hearing loss was found among workers who had worked for more than 10 years and declined in those who had worked for more than 20 years. This is similar to the observation made by Aliyu et al., in North West Nigeria, in which the majority of the participants worked for more than 10 years [16]. There was a statistically significant increase in pure-tone averages of subjects (p=0.000) when correlated with length of stay in the factory; workers with prolonged stay in the factory had their pure-tone average significantly increased [16].

Exposure to loud noise from all sources is the most common preventable cause of hearing loss and impairment [3]. This study has revealed a prevalence of high-intensity noise in the factory, ranging from 104dB-A in the power house to 76 dB-A in the mobile clinic in the noise-exposed region. The noise level was measured using an A-weighted network because of its simplicity and accuracy in rating hearing. Other researchers also recorded a high-intensity noise in their studies [17-19]. This may be due to the heavy machines and industrial equipment in use; the findings in this study therefore agreed with earlier findings, which stated that exposure to loud, distracting, and possibly hazardous noise is a common experience for everyone in the workplace [20].

Prevention of noise-induced hearing loss has been addressed by providing and wearing hearing protection devices and reducing noise emissions. For many occupations, this has been insufficient when noise levels exceed 130-140dB [18]. In this study, the use of hearing protection devices was very low among the noise-exposed workers, citing common reasons for lack of use of Hearing protection devices as non-availability (53.5%), discomfort, and lack of legislation compelling the workers to use the devices, even though the majority (98.2%) are aware of its importance. The findings from this study indicate that the workers are highly aware of the protection offered by the Hearing protection devices. Other researchers, however, noted that possessing knowledge of the detrimental effect of noise on hearing translates into regular use of hearing protective device [20,21]. Many studies revealed convincing evidence that the use of hearing protection devices is grossly inadequate in Africa, either due to lack of awareness on the part of the employees or lack of HCP in many factories [22-25]. Studies by Guo et al., in China reported a relatively high prevalence of use of hearing protective devices 69.47% [20]. The high prevalence of use of hearing protection devices in these studies might be due to the implementation of policies by the government compelling the factories to provide and ensure the use of these devices.

CONCLUSION

There was high-intensity noise exceeding the WHO- recommended limit of 85 dB-A for noise level in an industrial environment. There was a non-availability of the hearing protection device resulting in the use of the hearing protection device being very low.

REFERENCES

- Kerns E, Masterson EA, Themann CL, Calvert GM. Cardiovascular conditions, hearing difficulty, and occupational noise exposure within US industries and occupations. Am J Ind Med. 2018; 61; 477-491.

- Green DR, Masterson EA, Themann CL. Prevalence of hearing protection device non-use among noise-exposed US workers in 2007 and 2014. Am J Ind Med. 2021; 12: 1002-1017.

- Thai T, Ku?era P, Bernatik A. Noise Pollution and Its Correlations with Occupational Noise-Induced Hearing Loss in Cement Plants in Vietnam. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 8: 4229.

- Singh RV, Bhagat S, Sahni D, Aggarwal S, Kaur T. Noise Induced Hearing Loss among Industrial Workers in North Indi;: A Tale of Various Influencing Factors. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery. 2024; 6: 5369-5378.

- Azees AS, Ango JT, Isa A, Adeniyi A, Makinde A. Burden of noise-induced hearing loss among rice mill workers in Sokoto State, Northwest Nigeria. Niger J Basic Clin Sci. 2023; 20: 161-166.

- Lin HW, Furman AC, Kujawa SG, Liberman MC. Primary neural degeneration in the Guinea pig cochlea after reversible noise-induced threshold shift. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2011; 5: 605-616.

- Ismail AF, Daud A, Ismail Z, Abdullah B. Noise-induced hearing loss among quarry workers in a north-eastern state of Malaysia. Oman Med J. 2013; 5: 331-336.

- Melese M, Adugna DG, Mulat B, Adera A. Hearing loss and its associated factors among metal workshop workers at Gondar city, Northwest Ethiopia. Front Public Health. 2022; 10: 919-939

- Dudarewicz A, Pawlaczyk-?uszczy?ska M, Zaborowski K, Pontoppidan NH, Wolniakowska A, Bramsløw L, et al. The adaptation of noise-induced temporary hearing threshold shift predictive models for modelling the public health policy. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2023; 36: 125-138.

- Ali A, Garandawa HI, Nwawolo CN, Somefun OO. Noise-induced hearing loss at cement company, Nigeria. Online J Med Med Sci Res. 2012; 1: 49-54.

- Nyarubeli IP, Bråtveit M, Tungu AM, Mamuya SH, Moen BE. Temporary Threshold Shifts among Iron and Steel Factory Workers in Tanzania: A Pre-Interventional Study. Ann Glob Health. 2021; 87: 35.

- Collée A, Watelet JB, Vanmaele T, Thielen JV, Clarys P. Longitudinal changes in hearing threshold levels for noise-exposed military personnel. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2019; 92: 219-226.

- Sliwinska-Kowalska M. New trends in the prevention of occupational noise-induced hearing loss. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2020; 6: 841- 848.

- Lee SY, Seo HW, Jung SM, Lee SH, Chung JH. Assessing the accuracy and reliability of application-based audiometry for hearing evaluation. Sci Rep. 2024; 1: 577-735.

- Liu H, Fu X, Li M, Wang S. Comparisons of air-conduction hearing thresholds between manual and automated methods in a commercial audiometer. Front Neurosci. 2023; 17: 292-395.

- Aliyu N, Iseh KR, Mohammed A, Yikawe SS, Inoh MI, Manya C. Hearing loss among cement factory workers in Northwest Nigeria. Indian J Otol. 2020; 26: 173-178.

- Melese M, Adugna DG, Mulat B, Adera A. Hearing loss and its associated factors among metal workshop workers at Gondar city, Northwest Ethiopia. Front Public Health. 2022; 10: 919-939

- Kitcher ED, Ocansey G, Abaidoo B, Atule A. Occupational hearing loss of market mill workers in the city of Accra, Ghana. Noise Health. 2014; 70: 183-198.

- Olusanya BO, Davis AC, Hoffman HJ. Hearing loss grades and the International classification of functioning, disability and health. Bull World Health Organ. 2019; 7: 725-728.

- Guo J, Shu L, Wen W, Xu G, Zhan L, Yan M, et al. The influencing factors of hearing protection device usage among noise-exposed workers in Guangdong Province: a structural equation modeling-based survey. BMC Public Health. 2024; 1: 105-104

- Tafere GA, Beyera GK, Wami SD. The effect of organizational and individual factors on health and safety practices: results from a cross-sectional study among manufacturing industrial workers. J Public Health. 2020; 28: 173- 179.

- Liu S, Nkrumah ENK, Akoto LS, Gyabeng E, Nkrumah E. The State of Occupational Health and Safety Management Frameworks (OHSMF) and Occupational Injuries and Accidents in the Ghanaian Oil and Gas Industry: Assessing the Mediating Role of Safety Knowledge. Biomed Res Int. 2020; 2020: 6354895.

- Moroe NF. Occupational noise induced hearing loss in the mining sector in South Africa: Perspectives from occupational health practitioners on how mineworkers are trained. S Afr J Commun Disord. 2020; 67: e1-e6.

- Khoza-Shangase K, Moroe NF. Best practice for hearing conservation programmes in Africa. In: Khoza-Shangase K, Moroe NF, editors. Occupational Noise-Induced Hearing Loss: An African perspective. Cape Town: AOSIS; 2022.

- Cavallari JM, Burch KA, Hanrahan J, Garza JL, Dugan AG. Safety climate, hearing climate and hearing protection device use among transportation road maintainers. Am J Ind Med. 2019; 62: 590-599.