Cold Miliary: An Atypical Presentation of Thoracic Sarcoidosis

- 1. Department of Pulmonology and Respiratory Disease, 20 Aout 1953 Hospital, University Hospital Center of Casablanca, Morocco

Abstract

Sarcoidosis is an idiopathic systemic granulomatous disease of unknown etiology, characterized by fibrotic changes in tissue architecture and specifically by the presence of non-caseating epithelioid cell granulomas. We report the case of a cold miliary pattern diagnosed as atypical thoracic sarcoidosis, focusing on the challenges in establishing the diagnosis. The patient is a 38-year-old woman treated for lymph node tuberculosis at the age of 12. She presented with progressive dyspnea over one year, accompanied by a persistent dry cough, general health deterioration, and anxiety. An anti-tuberculous treatment was initiated empirically without bacteriological evidence, showing no improvement by the end of therapy. Subsequently, a chest CT scan revealed diffuse micronodules with a lymphatic distribution, associated with bilateral hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Bronchial biopsies showed non-necrotizing, non-caseating tuberculoid granulomatous inflammation. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels were elevated, and the 6-minute walk test revealed desaturation to 90% after a distance of 30 meters. A multidisciplinary team discussion concluded with the diagnosis of atypical thoracic sarcoidosis. The patient was started on corticosteroid therapy combined with adjuvant treatment for 14 months, showing favorable progression confirmed by a follow-up chest CT scan six months later.

KEYWORDS

- Thoracic Sarcoidosis

- Cold Miliary Pattern

- Young Woman

- Granulomatous Disease

- Atypical Dase

CITATION

Arfaoui H, Mouddene NA, Hallouli S, Msika S, Bamha H, et al. (2025) Cold Miliary: An Atypical Presentation of Thoracic Sarcoidosis. Clin Res Pulmonol 11(1): 1072.

INTRODUCTION

Sarcoidosis is a multisystemic granulomatous disease with a predilection for the mediastinal and pulmonary regions. It primarily affects multiple organs, notably the lungs and lymphatic system. Its cause remains unknown and is characterized by the formation of inflammatory-type granulomas. The diagnosis of thoracic sarcoidosis is not standardized and requires a combination of clinical, radiological, biological, and histological findings, including the presence of non-caseating epithelioid and giant cell granulomas and the exclusion of other causes of granulomatous diseases [1-2]. The radiological features of thoracic sarcoidosis vary, with typical patterns observed in 60–70% of patients and atypical patterns in 25–30%. In some sarcoidosis patients (5–10%), thoracic imaging may appear normal [3]. The objective of this case report is to present an atypical form of sarcoidosis, emphasizing the differential diagnosis to highlight the challenging role of radiologists in identifying the disease and to assist clinicians in establishing an accurate diagnosis.

CASE REPORT

The patient is a 38-year-old black woman with no significant medical habits or history aside from cervical lymph node tuberculosis diagnosed at the age of 12, confirmed histologically by a tuberculoid granuloma with caseous necrosis. She reported no recent contact with tuberculosis in her surroundings and had no other associated pathologies. The onset of her illness dates back six months, marked by the gradual appearance of intermittent dry cough and exertional dyspnea, without hemoptysis, chest pain, or other associated extra pulmonary symptoms. These symptoms evolved in a context of febrile sensations, night sweats, and a general health decline characterized by asthenia, anorexia, and unquantified weight loss. The patient consulted a pulmonologist who ordered a frontal chest X-ray and an Interferon-Gamma Release Assay (IGRA), which tested positive. Based on the radioclinical data, a multidisciplinary decision concluded a diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis, and a six- month anti-tuberculous treatment was initiated. After 1.5 months of treatment, the clinical course showed slight improvement with regression of functional symptoms and a weight gain of 2 kg (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Chest X-ray after 1.5 months of anti-tuberculous treatment.

However, at the end of the six-month anti-tuberculous treatment, the patient experienced clinical worsening with dyspnea progressing to Mmrc stage III, profound anxiety, and radiological deterioration. A follow-up chest X-ray revealed the presence of diffuse bilateral micronodules (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Chest X-ray after 6 months of anti-tuberculous treatment showing diffuse bilateral micronodule.

Examination on Admission

Upon admission to the hospital, the patient was in poor general condition (Performance Status: 2), slightly underweight (BMI = 17.5 kg/m²), eupneic at 20 breaths/min, afebrile, normotensive, and normocardic, with normal oxygen saturation in ambient air (SpO?: 96%). There were no signs of respiratory distress or cyanosis. Pulmonary examination revealed diffuse bilateral crackles. Cardiovascular examination showed no abnormalities. The skin and mucosal examination revealed no erythematous or nodular lesions, with a visible cervical scar from the previous lymph node biopsy on the right side. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. During hospitalization, temperature monitoring showed no episodes of fever.

Radiological Assessment

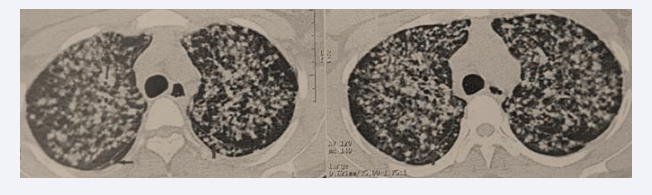

A chest CT scan revealed diffuse bilateral nodules and micronodules with a lymphatic distribution, involving all pulmonary regions and creating a miliary pattern. Some nodules were seen along the right and left fissures, forming a “beaded fissure” appearance (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Diffuse bilateral nodules and micronodules with lymphatic distribution, presenting a miliary pattern and perilymphatic fissure appearance.

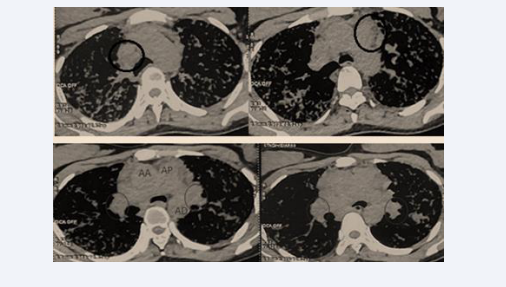

The mediastinal window demonstrated large bilateral hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathies (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Large bilateral hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathies.

An abdominopelvic ultrasound showed no digestive wall thickening or abdominal lymphadenopathy.

Biological Assessment

The complete blood count, liver, renal, and thyroid function tests were all within normal ranges. Blood and urinary phosphocalcium profiles were also normal (Calcemia: 104 mg/L, Phosphatemia: 40 mg/L, Urinary calcium: 39 mg/L, Urinary phosphate: <50 mg/L). Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) levels were elevated at 192 U/L. The 24-hour proteinuria was below 0.11 g/24h, and serum protein electrophoresis revealed inflammatory polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. The Quantiferon TB Gold test was negative.

Endoscopic Assessment

Flexible bronchoscopy revealed diffuse grade 2 inflammation in both the right and left bronchi, with mucous secretions but no granulomatous lesions. Segmental bronchial biopsies revealed non-necrotizing tuberculoid granulomatous inflammation, with no signs of malignancy. Acid-fast bacilli (AFB) staining, GeneXpert MTB/RIF, and culture from bronchial aspirates were negative. A labial biopsy demonstrated grade 1 chronic sialadenitis according to the Chisholm and Mason classification. Ophthalmological and otorhinolaryngological (ENT) examinations, including nasal biopsy, showed no evidence of sarcoid involvement.

Assessment of Functional Impact

Plethysmography revealed no obstructive ventilatory disorder (FEV1/FVC = 0.8, FEV1 = 95%) or restrictive ventilatory disorder (TLC = 99%). The six-minute walk test showed desaturation to 90% after walking a distance of 30 meters. Cardiac evaluation, including an electrocardiogram and echocardiography, showed no abnormalities.

Final Diagnosis

The diagnosis was confirmed as cold miliary sarcoidosis, classified as Stage III sarcoidosis. The case’s uniqueness lies in its atypical presentation.

Treatment

A multidisciplinary team decided to initiate corticosteroid therapy at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day for six weeks, followed by a gradual taper over a total duration of 14 months. Adjuvant therapy included potassium supplements, vitamin D, and a low- sodium, low-sugar diet.

Outcome

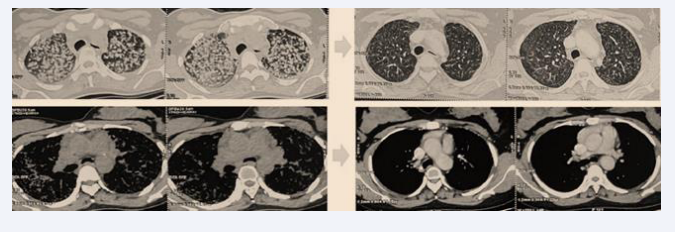

After two months of corticosteroid therapy, the patient showed significant improvement, with reduced dyspnea, disappearance of cough and anxiety, resolution of crackles, and a weight gain of 15 kg. At six months, dyspnea and crackles had completely disappeared, and the patient resumed her daily activities, including work. ACE levels showed a significant decrease (96 U/L vs. 192 U/L), and the six-minute walk test revealed normal oxygen saturation in ambient air (SpO? = 99%) after walking 280 meters without dyspnea. Follow-up chest CT showed a marked regression of nodules, micronodules, and hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Follow-up chest CT showing significant regression of nodules, micronodules, and hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

DISCUSSION

Sarcoidosis is an idiopathic systemic granulomatous disease of unknown etiology, characterized by fibrotic changes in tissue architecture and specifically by the presence of non-caseating epithelioid cell granulomas. In 90% of cases, pulmonary involvement associated with mediastinal hilar lymphadenopathy is present, but the disease can also affect other organs, including the skin, salivary glands, eyes, liver, heart, and brain [4]. The incidence of sarcoidosis varies depending on geographic region, sex—with a slight female predominance—race, and ethnic origin. Familial clustering of sarcoidosis has also been described [5]. Generally, sarcoidosis affects young adults between the ages of 20 and 29, with a slightly higher prevalence among women [6]. In our case, the patient is a young Black woman with no family history of sarcoidosis. Patients with sarcoidosis are typically symptomatic, presenting with non-specific symptoms such as cough, dyspnea, fatigue, night sweats, and erythema. Approximately 50% of patients remain asymptomatic, with incidental findings discovered during routine chest radiography [4]. The diagnosis relies on a combination of clinical and radiological findings, along with histological evidence of non- caseating epithelioid granulomas [3]. The differential diagnosis includes major infectious granulomatous disorders such as tuberculosis, leishmaniasis, fungal diseases, and non-infectious granulomatous disorders, including Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas, sarcomas, silicosis, berylliosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and vasculitis. Radiologically atypical forms, such as seen in our patient, pose a diagnostic challenge for both clinicians and radiologists, as they can mimic several other conditions, including tuberculous miliary disease, carcinomatous lymphangitis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and others. This is why thoracic sarcoidosis is often referred to as “the great imitator” [7]. Atypical manifestations may include honeycomb cysts, halo opacities, mosaic attenuation, miliary opacities, or pleural involvement (pneumothorax, pleural effusion, and pleural thickening). Most of these atypical forms are typically associated with older age (patients over 50 years) and a history of smoking, which was not the case with our patient [1].

CONCLUSION

Thoracic sarcoidosis is considered a heterogeneous disease, often referred to as “the great imitator”, due to its wide spectrum of typical and atypical radiological presentations. Clinicians and radiologists must carefully correlate imaging findings with clinical and histological results to confirm the diagnosis and rule out differential diagnoses. It is essential for radiologists and pulmonologists to become familiar with the broad range of imaging patterns associated with sarcoidosis to ensure an accurate and timely diagnosis of thoracic sarcoidosis.

REFERENCES

- Cozzi D, Bargagli E, Calabrò AG, Torricelli E, Giannelli F, Cavigli E, et al. Atypical HRCT manifestations of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Radiol Med. 2018; 123: 174-184. doi: 10.1007/s11547-017-0830-y. Epub 2017 Nov 9. PMID: 29124658.

- Crouser ED, Maier LA, Wilson KC, Bonham CA, Morgenthau AS, Patterson KC, et al. Diagnosis and Detection of Sarcoidosis. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020; 2018: e26-e51. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202002- 0251ST. PMID: 32293205; PMCID: PMC7159433.

- Criado E, Sánchez M, Ramírez J, Arguis P, de Caralt TM, Perea RJ, et al. Pulmonary sarcoidosis: typical and atypical manifestations at high- resolution CT with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2010; 30: 1567-1586. doi: 10.1148/rg.306105512. PMID: 21071376.

- Al-Jahdali H, Rajiah P, Koteyar SS, Allen C, Khan AN. Atypical radiological manifestations of thoracic sarcoidosis: A review and pictorial essay. Ann Thorac Med. 2013; 8: 186-196. doi: 10.4103/1817- 1737.118490. PMID: 24250731; PMCID: PMC3821277.

- Rybicki BA, Iannuzzi MC, Frederick MM, Thompson BW, Rossman MD, Bresnitz EA, et al; ACCESS Research Group. Familial aggregation of sarcoidosis. A case-control etiologic study of sarcoidosis (ACCESS). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001; 164: 2085-2091. doi: 10.1164/ ajrccm.164.11.2106001. PMID: 11739139.

- Hillerdal G, Nöu E, Osterman K, Schmekel B. Sarcoidosis: epidemiology and prognosis. A 15-year European study. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984; 130: 29-32. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.130.1.29. PMID: 6742607.

- Hawtin KE, Roddie ME, Mauri FA, Copley SJ. Pulmonary sarcoidosis: the ‘Great Pretender’. Clin Radiol. 2010; 65: 642-50. doi: 10.1016/j. crad.2010.03.004. Epub 2010 May 13. PMID: 20599067.