Cutaneous Metastatis Revealing Neuroendocrin Pulmonar Carcinoma

- 1. Department of Respiratory Disease of “20 Août 1953” Hospital, Ibn Rochd University Hospital, Morocco

Citation

Arfaoui H, Zadi M, Msika S, Bamha H, Bougteb N, et al. (2025) Cutaneous Metastatis Revealing Neuroendocrin Pulmonar Carcinoma. Clin Res Pulmonol 11(1): 1074.

INTRODUCTION

Cutaneous metastasis accounts for only 2% of all skin cancers . The importance of prompt recognition of a cutaneous metastasis is highlighted by the fact that it can be the first clinical sign of a new or recurrent malignancy [1]. Although classically appearing as a dermal nodule the clinical appearance of cutaneous metastases can vary widely [2,3]. Pulmonary Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma (LCNEC) is a rare subtype of malignant pulmonary tumor. The incidence rate of LCNEC was reported to be 0.3%–3% in lung cancers. Although LCNEC is classified as Non Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC), it is more aggressive and malignant than other NSCLC. Cutaneous metastasis of neuroendocrine carcinoma is uncommon and they can be easily misdiagnosed as benign epidermal cysts or Merkel cell carcinoma.

CASE REPORT

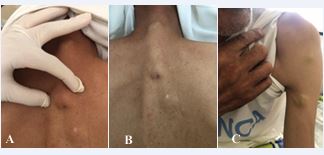

It concerns a 60-year-old patient, a chronic smoker with a history of 92 pack-years, followed for dysuria due to prostatic pathology for the past 8 years. The patient was admitted for a right pneumothorax of low abundance due to a right mediastinopulmonary process revealed by diffuse thoracic pain, cough, and stage 3 dyspnea according to mMRC with episodes of low abundance hemoptysis occurring for the past 6 months In a context of afebrile condition and general state decline, clinical examination revealed a syndrome of air effusion in the lower 2/3 of the right hemithorax with firm indolent subcutaneous nodular lesions on the trunk and arms A skin biopsy was performed revealing a focal necrotic invasive tumour proliferation. The tumour cells were small to medium in size, with hyperchromatic and aniscokaryotic nuclei and minimal cytoplasm with the presence of crush artefact. This tumour proliferation is located in the dermis and does not infiltrate the epidermis, suggesting a poorly differentiated invasive carcinoma (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Cutaneous Nodules.

The immunohistochemical study showed that the tumour cells express TTF1, synaptophysin, focal weak CK20, focal CD56, focal weak CK7 but do not express chromagranin A.In favour of a cutaneous location of a small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, TTF1 indicates its primary pulmonary origin.

DISCUSSION

Skin metastases are not uncommon, affecting approximately 3 to 10% of cancer patients [1,2]. The majority of skin metastases originate from a melanoma, a cutaneous-mucosal or neuroendocrine carcinoma, typically detected following the discovery of the primary neoplasm. While any cancer type can metastasize to the skin, it most commonly occurs after the primary cancer has been diagnosed. Occasionally, however, a skin metastasis may occur simultaneously with the revelation of the primary cancer. In some instances, the metastasis may present in isolation, even when the primary cancer has not yet been detected or has completely regressed [3]. In men, this situation may prompt exploration for lung or renal cancer, whereas in women, special attention should be given to the kidneys and ovaries [4]. Very late metastases, persisting beyond 10 years post the eradication of the primary neoplasm, are possible, particularly in the cases of melanomas and certain type of breast cancer, kidney cancer, of the bladder, colon, prostate, ovary and larynx. There are several distinct pathways for metastatic dissemination to the skin. Direct extension of the neoplasm through contiguity is possible and is even common, especially in the case of breast cancer. Dissemination through lymphatic or hematogenous routes is classically recognized. Another possibility is dissemination during surgical intervention on the primary neoplasm. A separate pathway, apparently characteristic of melanoma, involves the migration of neoplastic cells along the external surface of vessels [3,5]. Clinical presentations of metastases vary. So, it’s true that there is a proximity relationship between the primary cancer and cutaneous metastatic locations. Metastatic nodules are generally few in number and may exhibit regional clustering depending on the nature of the primary cancer. They are firm and typically painless, reaching a diameter of a few centimeters and appearing suddenly. Their growth is usually rapid before stabilizing in expansion, without a spontaneous tendency for progression. Occasionally, metastases may become bullous or eroded. Others have an inflammatory erysipeloid appearance [6], or even a sclerotic or armor like presentation. Metastases from pulmonary neoplasms predominantly localize on the chest [7]. Cells from the colon and rectum most often manifest on the abdominal wall, particularly at a scar site, and in the perineal region [7]. The Sister Mary-Joseph nodule located at the umbilicus is often associated with neoplasms of the stomach, large intestine, ovary, or pancreas [8,9].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, cutaneous metastases of pulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas represent a rare but significant manifestation of tumor dissemination. Their presence often poses a diagnostic challenge due to clinical resemblance to other skin lesions. A multidisciplinary approach involving dermatologists, oncologists, and pathologists is essential to confirm diagnosis and develop an appropriate treatment plan. Advances in medical imaging and tissue biopsy have greatly improved our ability to detect these metastases early, allowing for more effective therapeutic intervention. Furthermore, a better understanding of the molecular biology of pulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas and their cutaneous metastases paves the way for new targeted therapeutic strategies. Overall, an integrated approach and close monitoring are necessary to optimize the management of patients with cutaneous metastases of pulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas, with the goal of improving clinical outcomes and quality of life.

REFERENCES

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A, Kutzner H, Requena L. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012 ; 34: 347-393.

- Gan EY, Chio MT, Tan WP. A retrospective review of cutaneous metastases at the National Skin Centre Singapore. Australas J Dermatol. 2015; 56: 1-6.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993; 29: 228-236.

- Asamura H, Kameya T, Matsuno Y, Noguchi M, Tada H, Ishikawa Y, et al. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the lung: a prognostic spectrum. J Clin Oncol. 2006; 24: 70-76.

- Barnhill RL, Lugassy C. Angiotropic malignant melanoma and extravascular migratory metastasis: description of 36 cases with emphasis on a new mechanism of tumour spread. Pathology. 2004; 36: 485-490.

- Zangrilli A, Sarrasin R, Sarmati L, Orlandi UN, Blanchi L, Chimenti SE. Métastases cutanées rysipéloïdes de la vessiecarcinome. EUR J Dermatol. 2007; 17: 534-536.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995; 33: 161-182.

- Powell FC, Tonnelier UN J, Massa MC, Göllner JR, Su WP. SsoeurMarie- Joseph nodule : une clinique et histologique étude. J SuisAcad Dermatol. 1984; 10: 610-615.

- Kort R, Fazaa B, Zermani R, Letawe C, Kamoun MR, Piérard GE. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule and inaugural cutaneous metastases of gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas. Acta Clin Belg. 1995; 50: 25-27.