Silicosis-Tuberculosis in Jerada (Morocco) Epidemiological, Clinical, Therapeutic and Evolutionary Aspects

- 1. Department of Pneumology and Silicosis, Jerada Provincial Hospital, Morocco

Summary

Objective: Tuberculosis is a frequent and serious complication of silicosis. The aim of this study is to describe the epidemiological, clinical, therapeutic and evolutionary aspects of this pathology, therapeutic and evolutionary aspects of silicotuberculosis.

Patients and Methods: This study concerns 28 cases of silicotuberculosis collected at the CDTMR (Diagnostic centre for tuberculosis and respiratory diseases) of Jerada (Morocco) over a period of 3 years (2021-2023).

Results: All patients were male former coal mine workers in Jerada. Symptoms were dominated by dyspnoea and persistent bronchial syndrome. The diagnosis of tuberculosis was confirmed by isolation of Koch’s bacillus from sputum, by isolation of BAARs by direct examination in 15 cases, by GeneXpert in 7 cases, by histological examination of biopsies in two cases and by ADA (adenosine deaminase) assay in 2 cases; the diagnosis of tuberculosis was retained on the basis of radio-clinical /argument in two silicotic cases. Anti-bacillary treatment was started in all patients, with a good clinical outcome in 21 cases. There were 5 deaths and 2 cases of recurrence.

Conclusion: Silicosis increases the risk of tuberculosis, hence the importance of screening for tuberculosis in any patient suffering from silicosis.

KEYWORDS

- Silicosis

- Jerada

- Tuberculosis

- Pulmonary

- Coal Miners

CITATION

Rachid T, Kouismi H (2024) Silicosis-Tuberculosis in Jerada (Morocco) Epidemiological, Clinical, Therapeutic and Evolutionary Aspects. Clin Res Pulmonol 10(2): 1071.

INTRODUCTION

Silicosis is one of the most important occupational diseases and a public health problem worldwide, particularly prevalent in low- and middle-income countries [1,2]. It is a potentially fatal, irreversible, fibrosing lung disease caused by the inhalation of respirable free crystalline silica [3], first described by Visconti in 1870 [4], and is a preventable occupational disease associated with a number of pathologies, in particular tuberculosis. The risk of developing silicosis-induced tuberculosis and the risk of mortality from silicosis-induced tuberculosis are higher than in the general population [5,6]. The aim of this study was to examine the effect of exposure to silica on the prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective descriptive study. The study took place in the CDTMR centre (Diagnostic Centre for Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases) in the town of Jerada. The town of Jerada is part of the Eastern region, 60 km south of Oujda (Morocco), close to the border with Algeria. Since its start-up in 1932, the mine has exploited an average intrinsic anthracite deposit (high ash and sulphur content) in difficult conditions. Jerada will experience a decline in population numbers from 60,000 thousand inhabitants in 1994 to 41,014 at present according to the 2024 census [7]. This is essentially due to the migration experienced by the town following the cessation of mining activity in 2001 [8]. At the Jerada Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases Diagnostic Centre, we collected 28 cases over a 36-month period from January 2021 to December 2023. Silicotic patients with a form of tuberculosis were included in the study and their medical records were collected and analyzed.

RESULTS

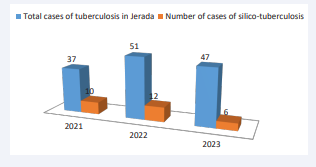

All our patients were male. They were former underground miners in the coalmines of Jerada, Regarding place of residence: 24 patients lived in urban areas and 4 patients in rural areas. The duration of the study was 3 years; the distribution of the cases according to the year was 10 patients in 2021, 12 patients in 2022 and 6 cases in 2023. The average age was 67, with extremes ranging from 50 to 92. (Table 1), (Figure 1) shows the distribution of patients by age group, with the majority aged over 60.

Table 1: Breakdown of patients by age group.

|

Age group |

Number of patients |

percentage |

|

Under than 60 years |

7 |

25% |

|

Between 60-70 years |

10 |

36% |

|

Older than 70 years |

11 |

39% |

Figure 1: Distribution of tuberculosis and silico-tuberculosis cases in our study (N = 28).

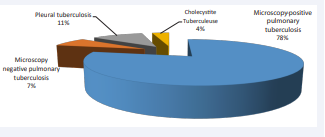

The associated co morbidities were arterial hypertension in 4 cases, diabetes in 3 cases and a history of treated tuberculosis in 2 cases. Active smoking was found in 6 patients. Clinical symptoms included dyspnoea in 72% of cases, productive cough in 64% of cases, and a decline in general condition in all cases. Regarding the form of tuberculosis, the majority (24 cases) were pulmonary, while 4 cases of extra-pulmonary tuberculosis were found, including 3 cases of pleural tuberculosis and 1 rare case of biliary localisation.

Means of diagnosis of tuberculosis in silicotic patients: BK research was positive in 22 cases: 15 patients by isolation of BK by direct examination, while GeneXpert allowed the discovery of 7 cases, histological data from pleural biopsies in 2 cases and ADA dosage in 2 cases. The clinical and radiological arguments allowed us to conclude to retain two microscopically negative TPM cases. Bronchoscopy had been performed in 2 patients. (Figure 2 and 3),

Figure 2: Distribution of cases according to the form and location of tuberculosis in our study.

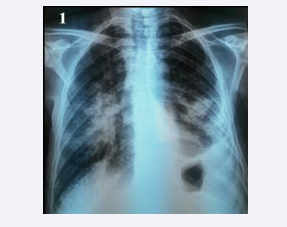

Figure 3: Standard frontal chest X-ray showing bilateral heterogeneous pseudotumour opacities with an appearance of left pleural effusion. Pleural puncture and biopsy revealed tuberculous pleurisy.

According to the recommendations of the national anti-tuberculosis programme, the rapid HIV test, carried out systematically in all our patients after confirmation of tuberculosis, was negative in all cases. Therapeutic management was based on the treatment of complications, in particular antibacillary drugs in 20% of cases, according to the 2RHZE/4RH regimen (two months of rifampicin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide and etambutol, followed by four months of rifampicin and isoniazid) in all cases, and according to the new regimen of the Moroccan anti-tuberculosis programme. Long-term oxygen therapy was recommended for three patients. Progression was good in 75% of cases. We noted 5 cases of death and 2 cases of recurrence. Silicotuberculosis is a notifiable occupational disease. All our patients had worked for coal-mining companies in Morocco and received compensation.

DISCUSSION

Silicosis is an old occupational disease and the most common form of pneumoconiosis [9]. It is caused by inhalation of free crystalline silica (quartz, cristobalite, tridymite) over several years [10]. These results are similar and comparable to those found by other authors in Mali and Morocco [11-15]. Silicosis is recognised as an occupational disease [16,17]. However, right heart failure, pneumothorax, COPD, autoimmune diseases (scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis), chronic kidney disease and the risk of lung cancer are frequent complications of silicosis, as reported in various studies [18-21].

However, tuberculosis is the main complication; According to the literature, the risk of developing pulmonary tuberculosis in silicosis is higher (2.8 to 39 times higher, depending on the severity of the silicosis) than that observed in healthy controls. The risk of developing extra-pulmonary tuberculosis due to silicosis is 3.7 times higher than for healthy controls [21-24]. More recent results show that exposure to silica, even without silicosis, can also predispose individuals to tuberculosis [25,26]. This may be explained by silica altering the immune response of the lungs, altering the metabolism and function of pulmonary macrophages and, with increasing frequency of exposure, their apoptosis [23]. However, the risk of pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis persists for life even after cessation of exposure [22,27]. The bacillus may remain encapsulated within silicosis nodules, and is thought to be responsible for the reactivation of tuberculosis in these patients [26].

In our series, the diagnosis of silicosis was made on the basis of exposure to silica dust and compatible radiological images. Superinfection with tuberculosis was suspected mainly on clinical grounds (persistent cough and decline in general condition in most patients) and on radiographic images, mainly in 2 patients who had excavated opacities. The diagnosis was confirmed by direct examination and sputum culture in the majority of cases. Pleural biopsies carried out in 2 patients contributed to the diagnosis by revealing an epithelio-gigantocellular granuloma with caseous necrosis. However, the diagnosis of active tuberculosis complicating silicosis can sometimes be very difficult, as the clinical manifestations are non-specific and the radiological lesions cannot be distinguished from those resulting from pre-existing silicosis [28]. In the literature, in the event of clinical suspicion of concomitant active tuberculosis (persistent cough, haemoptysis, weight loss, fever, etc.), an appropriate additional investigation should be carried out. A chest X-ray is recommended, as well as a smear and sputum culture, or even induced sputum culture if necessary, given its good sensitivity [5,29]

Where there is any doubt about the presence of active tuberculosis, bronchoscopy with Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL) may be performed, in conjunction with transbronchial biopsy where possible. According to Charoenratanakul et al [30], bronchial biopsies significantly increase the diagnostic yield of bronchoscopy, especially in patients whose sputum and BAL are negative for BK. Chest CT, despite its high sensitivity, is reserved for cases of clinical or radiological doubt. The main findings compatible with active tuberculosis in silicosis were thick- walled cavities, condensations, images with a bud-tree pattern, asymmetric nodular images and rapid progression of the disease [31,32].

The association of silicosis and HIV infection considerably increases the risk of tuberculosis [33]. Smoking is another aggravating factor [34,35], and was found in 6 patients in our series. Smoking habits increase the prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis in silicosis patients. This finding is consistent with that of Sherson D, from the Department of Occupational Medicine in Denmark [36]. The literature shows that silicotics who smoke have a very high risk of developing pulmonary tuberculosis or lung cancer compared with non-smoking silicotics [14]. In his study, Leung [23] found a significant relationship between smoking and tuberculosis in silicotic subjects. He confirmed in his conclusion that silicotic smokers had a greater risk of tuberculosis than non- smoking silicotics. Finally, after ruling out active tuberculosis, treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in people with silicosis is recommended [37] and may be justified even in those exposed to silica who have not developed the disease [22,25].

Therefore, it is advisable to prescribe prophylactic treatment in all cases of silicosis and/or those exposed to silica dust for more than 10 years and with very positive tuberculin test results, but after eliminating cases of active tuberculosis. Study protocols to validate this approach have not yet been developed [5]. In Morocco today, pending validated international guidelines, no anti-tuberculosis chemoprophylaxis in workers with silicosis and/or just exposed to silica is indicated. There is currently no curative treatment for silicosis. Silicosis is an occupational disease recognised in Morocco and eligible for compensation under (Table 2 and 3) of occupational diseases. Its association with tuberculosis increases compensation.

Table 2: Distribution of patients according to the means used to diagnose tuberculosis.

|

Means of diagnosis |

Number of patients |

percentage |

|

|

Search BK |

By Direct Examination |

15 |

53% |

|

By GeneXpert |

7 |

25% |

|

|

Histological sampling |

2 |

7% |

|

|

Search for ADA in pleural fluid |

2 |

7% |

|

Table 3: Breakdown of patients by type of progression.

|

Evolution |

Number of patients |

percentage |

|

Favorable |

20 |

75% |

|

Death |

5 |

18% |

|

Relapses |

2 |

7% |

CONCLUSION

The importance of regular monitoring of workers exposed to silica is stressed, in order to detect the first cases of silicosis and potential complications, especially tuberculosis, which is the main cause. This could help slow the progression of silicosis and reduce disability, prevent tuberculosis and the risk of its spread to other workers.

REFERENCES

- WHO. The Global Occupational Health Network newsletter: Elimination of silicosis. Gohnet Newsletter. 2007; 12.

- Dumontet C, Vincent M, Laennec E, Girodet B, Vitrey D, Meram D, et al. Silicosis due to inhalation of domestic cleaning powder. Lancet. 1991; 338: 1085. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91946-r. PMID: 1681390.

- Madl AK, Donovan EP, Gaffney SH, McKinley MA, Moody EC, Henshaw JL, et al. State-of-the-science review of the occupational health hazards of crystalline silica in abrasive blasting operations and related requirements for respiratory protection. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2008; 11: 548-608. doi: 10.1080/10937400801909135.PMID: 18584454.

- Greenberg MI, Waksman J, Curtis J. Silicosis: a review. Dis Mon. 2007; 53: 394-416. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2007.09.020. PMID:17976433.

- Barboza CE, Winter DH, Seiscento M, Santos Ude P, Terra Filho M. Tuberculosis and silicosis: epidemiology, diagnosis and chemoprophylaxis. J Bras Pneumol. 2008; 34: 959-66. English, Portuguese. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132008001100012. PMID: 19099104.

- Nasrullah M, Mazurek JM, Wood JM, Bang KM, Kreiss K. Silicosis mortality with respiratory tuberculosis in the United States, 1968- 2006. Am J Epidemiol. 2011; 174: 839-848. doi: 10.1093/aje/ kwr159. Epub 2011 Aug 9. PMID: 21828370.

- https://www.hcp.ma/file/242229/

- https://www.entreprises-coloniales.fr/afrique-du-nord/ Charbonnages_de_Djerada.pdf

- Jalloul AS, Banks DE. The health effects of silica exposure. In: Rom WN, Markowitz S (eds). Environmental and occupation al medicine: Ed Lippincott Williams Wilkins, 2007; 365-387.

- Safa WF, Machado JL. Silicosis in a housewife. Saudi Med J. 2003; 24: 101-103. PMID: 12590288.

- Toloba Y, Sissoko BF, Badoum G, Nenzeko RT, Ouattara K, Soumaré D, et al. Poumon de puisatier au Mali pendant la décennie 2001- 2010 [Well-digger’s lung in Mali during the decade of 2001-2010]. Rev Pneumol Clin. 2014; 70: 208-213. French. doi: 10.1016/j.pneumo.2013.12.003. Epub 2014 Mar 16. PMID: 24646778.

- Kayantao D, Keita B, Kane M, Sangare´ S. Aspects radio-cliniques du poumon de puisatier observe´s en milieu hospitalier spécialisé a Bamako. Afr Biomed 1998; 3: 48-51.

- Amal Moustarhfir E, Nahid Zaghba, Hanane Benjelloun, Najiba, Yassine. Poumon du Puisatier. The Pan Afican Medical Journal 2016; 25: 157.

- Laraqui CH, Laraqui O, Alaoui A, EL Kabouss Y, Coll ET. Evaluation des risques respiratoires chez les puisatiers de la région d’Agadir, Maroc. Arch Mal Prof Med Trav 2004; 65: 480-488.

- Elkard I, Zaghba N, Benjelloun H, Bakhatar A, Yassine N. La silicotuberculose [Silicotuberculosis]. Rev Pneumol Clin. 2016; 72: 179-183. French. doi: 10.1016/j.pneumo.2015.10.003. Epub 2016 Jan 12. PMID: 26790716.

- Rice FL. Crystalline silica, quartz. Concise international chemical assessment document, 24. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000.

- Jalloul AS, Banks DE. The health effects of silica exposure. In:Rom WN, editor. Environmental and occupational medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. 365-387.

- Anthoine D, Lamy P, De Ren G, Dechoux J, Graimprey J. La pneumoconiose des maçons fumistes de lorraines. Arch Mal Prof Med Trav Sec Soc 1979; 40: 45-47.

- Fan YG, Jiang Y, Chang RS, Yao SX, Jin P, Wang W, et al. Prior lung disease and lung cancer risk in an occupational-based cohort in Yunnan, China. Lung Cancer. 2011; 72: 258-263. doi: 10.1016/j. lungcan.2011.01.032. Epub 2011 Mar 1. PMID: 21367481.

- Fernández Álvarez R, Martínez González C, Quero Martínez A, Blanco Pérez JJ, Carazo Fernández L, Prieto Fernández A. Guidelines for the diagnosis and monitoring of silicosis. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015; 51: 86-93. English, Spanish. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2014.07.010. Epub 2014 Dec 3. PMID: 25479706.

- Calvert GM, Rice FL, Boiano JM, Sheehy JW, Sanderson WT. Occupational silica exposure and risk of various diseases: an analysis using death certificates from 27 states of the United States. Occup Environ Med. 2003; 60: 122-129. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.2.122. PMID:12554840; PMCID: PMC1740467.

- teWaternaude JM, Ehrlich RI, Churchyard GJ, Pemba L, Dekker K, Vermeis M, et al. Tuberculosis and silica exposure in South African gold miners. Occup Environ Med. 2006; 63: 187-192. doi: 10.1136/ oem.2004.018614. PMID: 16497860; PMCID: PMC2078150.

- A double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial of three antituberculosis chemoprophylaxis regimens in patients with silicosis in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Chest Service/Tuberculosis Research Centre, Madras/British Medical Research Council. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992; 145: 36-41. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.1.36. PMID:1731596.

- Corbett EL, Churchyard GJ, Clayton T, Herselman P, Williams B, Hayes R, et al. Risk factors for pulmonary mycobacterial disease in South African gold miners. A case-control study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999; 159: 94-99. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9803048. PMID:9872824.

- Cowie RL. The epidemiology of tuberculosis in gold miners with silicosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994; 150: 1460-1462. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.5.7952577. PMID: 7952577.

- Hnizdo E, Murray J. Risk of pulmonary tuberculosis relative to silicosis and exposure to silica dust in South African gold miners. Occup Environ Med. 1998; 55(7):496-502. doi: 10.1136/oem.55.7.496.Erratum in: Occup Environ Med 1999; 56: 215-216. PMID: 9816385; PMCID: PMC1757613.

- Park HH, Girdler-Brown BV, Churchyard GJ, White NW, Ehrlich RI. Incidence of tuberculosis, HIV, and progression of silicosis and lung function impairment among former Basotho gold miners. Am J Ind Med. 2009; 52: 901-908. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20767. PMID: 19882740.

- Snider DE Jr. The relationship between tuberculosis and silicosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978; 118: 455-460. doi: 10.1164/ arrd.1978.118.3.455. PMID: 707873.

- Conde MB, Soares SL, Mello FC, Rezende VM, Almeida LL, Reingold AL, et al. Comparison of sputum induction with fiberoptic bronchoscopy in the diagnosis of tuberculosis: experience at an acquired immune deficiency syndrome reference center in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000; 162: 2238-2240. doi: 10.1164/ ajrccm.162.6.2003125. PMID: 11112145.

- Charoenratanakul S, Dejsomritrutai W, Chaiprasert A. Diagnostic role of fiberoptic bronchoscopy in suspected smear negative pulmonary tuberculosis. Respir Med. 1995; 89: 621-623. doi: 10.1016/0954-6111(95)90231-7. PMID: 7494916.

- Chong S, Lee KS, Chung MJ, Han J, Kwon OJ, Kim TS. Pneumoconiosis: comparison of imaging and pathologic findings. Radiographics. 2006; 26: 59-77. doi: 10.1148/rg.261055070. PMID: 16418244.

- Leung CC, Yu IT, Chen W. Silicosis. Lancet. 2012; 379: 2008-2018. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60235-9. Epub 2012 Apr 24. PMID: 22534002.

- Corbett EL, Churchyard GJ, Clayton TC, Williams BG, Mulder D, Hayes RJ, et al. HIV infection and silicosis: the impact of two potent risk factors on the incidence of mycobacterial disease in South African miners. AIDS. 2000; 14: 2759-2768. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200012010-00016. PMID: 11125895.

- Leung CC, Yew WW, Law WS, Tam CM, Leung M, Chung YW, et al. Smoking and tuberculosis among silicotic patients. Eur Respir J. 2007; 29: 745-750. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00134706. Epub 2006 Dec 20. PMID: 17182648.

- van Zyl Smit RN, Pai M, Yew WW, Leung CC, Zumla A, Bateman ED, et al. Global lung health: the colliding epidemics of tuberculosis, tobacco smoking, HIV and COPD. Eur Respir J. 2010; 35: 27-33. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00072909. PMID: 20044459; PMCID: PMC5454527.

- Sherson D, Lander F. Morbidity of pulmonary tuberculosis among silicotic and nonsilicotic foundry workers in Denmark. J Occup Med. 1990; 32: 110-113. PMID: 2303918.

- Adverse effects of crystalline silica exposure. American Thoracic Society Committee of the Scientific Assembly on Environmental and Occupational Health. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997; 155: 761-768. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032226. PMID: 9032226.

- Gerhardsson G. The end of silicosis in Sweden-a triumph for occupational hygiene engineering. OSH & Development. 2002; 13-25.