The Role of Dermatan Sulfate in the Nervous System

- 1. Laboratório Integrado de Biociências Translacionais, Instituto de Biodiversidade e Sustentabilidade, NUPEM/UFRJ, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil

- 2. Laboratório de Biologia Celular e Tecidual , Centro de Biociências e Biotecnologia, Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense Darcy Ribeiro, Brasil

- 3. Pós-Graduação em Biociências e Biotecnologia, Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense Darcy Ribeiro, Brasil

Abstract

A lot of evidence suggests the crucial role of dermatan sulfate (DS), a glycosaminoglycan (GAG) present in the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the central nervous system (CNS), in brain development, neuritogenesis, neuroprotection, and neuronal dysfunctions. Among these events, the involvement of DS during the development of the CNS has attracted attention to better comprehend its specific action in the neuroregeneration process. The various functions of DS can be mainly attributed to the structural variability of its disaccharides. Older and more recent reports about the relationship between the structure of DS and its function are helping to point out novel neurobiological roles for DS, increasing the understanding of a great range of biological functions of this molecule in the brain. Here we reviewed the recent knowledge about the function of DS, mainly in the neuritogenesis of the CNS. Furthermore, we indicate the importance of extending the in vitro and in vivo studies of the use of DS from marine organisms in the search for future therapeutic strategies.

Keywords

Glycosaminoglycan; Neuritogenesis; Extracellular matrix; Nuroprotection.

Citation

de Sousa GF, Giraldi-Guimarães A, de Barros CM (2021) The Role of Dermatan Sulfate in the Nervous System. JSM Cell Dev Biol 7(1): 1026.

ABBREVIATIONS

Akt: protein kinase B; AMPA: α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl4-isoxazolepropionic acid; BBB: Blood Brain Barrier; BDNF: Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor; CNS: Central Nervous System; CS: Chondroitin Sulfate; CS-E: GalNAc(4,6-SO4) units; CSPG: Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycan; DS4ST1: DS-specific 4-O-Sulfotransferase; GalNAc4S-6ST: N-acetylgalactosamine 4-sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase; UST: Uronyl 2 Sulfotransferase; ECM: Extracellular Matrix; FGF: Fibroblast Growth Factor; GAG: Glycosaminoglycan; GalNAc: N-acetyl-D-galactosamine; GAP-43: Growth Associated Protein 43; HA: Hyaluronan; HA: Hyaluronan; HCII: Heparin Cofactor II; HGF: Hepatocyte Growth Factor; HP: Heparin; HS: Heparan Sulfate; iA: IdoUA-GalNAc (4S); iB: IdoUA (2S)-GalNAc (4S); iC: IdoUA-GalNAc(6S); iD: IdoUA(2S)- GalNAc(6S); IdoA: L-iduronic acid; iE: IdoUA-GalNAc(4S, 6S); iO: IdoUA-GalNAc (iO); KS: Keratan Sulfate; MK: Midkine; mTOR: Mammalian Target Rapamycin; NGF: Nerve Growth Factor; NgR: Nogo Receptor; NMDA: N-MethylD-Aspartate; NSCs: Neurogenesis of Neural Stem Cells; NSF: N-ethylmaleimide Sensitive Factor; PNNs: Perineuronal Nets; PSD95: Postsynaptic Density 95; PTN: Pleiotrophin; RPTPs: Receptor Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases; SEMA3s: Class III Semaphorins; SYN: Synaptophysin; UST: Uronyl 2-O-sulfotransferase; VEGF: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor; Wg: Wingless; Wnt-3a: Wingless/int-3a

INTRODUCTION

The extracellular matrix (ECM) in the nervous system is a complex meshwork of supporting molecules arranged in a diffused way around the cell surface and/or associated with it. This ECM usually presents net-like formations surrounding neural cells. It is fundamental in maintaining the homeostasis of the CNS, acting as a scaffold for it and harboring chemical signaling molecules that are important for several neural processes, both in physiological processes and in neural diseases [1-3].

A lot of evidence suggests the involvement of dermatan sulfate (DS), a glycosaminoglycan (GAG) present in the ECM of the CNS, in brain development, neuritogenesis, and neuronal dysfunctions. The main DS involved in neuritogenic activity is composed by oversulfated disaccharides that contain L-iduronic acid (IdoA) residues [4]. IdoA occurs in variable proportions in DS and, as a result of the different position of the carboxyl moiety together with the different pattern of sulfation found in its disaccharides, it generates a more flexible polysaccharide chain, allowing specific interactions with several proteins and other polysaccharides. Thus, it has been suggested that DS has many potential neurobiological functions [5,6].

DS is found relatively late in the evolutionary tree, first appearing in the Echinodermata and Mollusca group of the animal kingdom [7]. It has been found in some invertebrate species and in the whole vertebrates group (subphylum Vertebrata) and it is absent in the Nematoda, Platyhelminthes, Coelenterata, and Porifera animal groups [8-11]. Moreover, DS has been found in large amounts in the tissues of some marine invertebrate species, which represents a good source for its purification.

In this review, we will describe the role of DS in neuritogenesis, demonstrating the importance of this molecule in potential therapeutic strategies.

Glycosaminoglycans

GAGs are considered a fraction of the glycoconjugates in the cell membranes, in the ECM, and in some cell granules of all tissues. The ability to connect protein to protein or enable protein interactions is identified as an important determinant of the cellular response to development, homeostasis, and disease [13,14]. GAGs can act as a physical and biochemical barrier, creating specific microenvironments around cells. They build size-selective barriers that are permeable only by small entities such as Ca2+ and Na+ that can freely diffuse and promote extracellular cation homeostasis [15].

GAGs are long, non-branched polysaccharides composed of repeating disaccharide regions of uronic acid (D-glucuronic acid or IdoA) and an amino sugar (D-galactosamine or D-glucosamine) or galactose [16]. They are distinguished from each other by the type of hexose, hexosamine, or hexuronic acid unit present and by the geometry of the glycosidic linkage between the repeated units [17].

Based on the difference in the repeating disaccharide units comprising GAGs, they can be categorized into six main groups: heparin (HP), heparan sulfate (HS), chondroitin sulfate (CS), dermatan sulfate (DS), keratan sulfate (KS), and hyaluronic acid (HA) [18].

Biosynthesis involves several enzymes that assemble the GAG backbone and subsequently add sulfate in their disaccharide at specific positions, except HA, which is a non-sulfated GAG [19]. Chains are synthesized by the attachment of a tetrasaccharide linker, which is covalently attached to the protein core. Following attachment of the linker to the protein core, the chain of glucosamine, galactosamine, or galactose is transferred, determining which type of GAG is produced [20,21]. Subsequently, the sugar chains are extended by the addition of two alternating monosaccharides, either N-acetylgalactosamine/glucuronic acid in chondroitin sulfate/DS or N-acetylglucosamine/glucuronic acid in heparin/heparan sulfate, on the tetrasaccharide linker [22,23].

These GAG chains are modified by sulfation at various hydroxy group positions and also by the epimerization of uronic acid residues during the biosynthetic process, thereby giving rise to structural diversity, which plays an important role in a wide range of biological functions, including cell proliferation, tissue morphogenesis, infections by viruses, and interactions with growth factors, cytokines, morphogens, and neuritogenesis [24].

Dermatan Sulfate

DS synthesis occurs by the alternate addition of L-iduronic acid (IdoA) and N-acetyl-D-galactosamine (GalNAc) residues to a protein core. Many of the GlcA residues become epimerized at C-5 to yield IdoA. Subsequently, O-sulfation may occur at the C-4 [by dermatan 4-sulfate sulfotransferase 1 (D4ST1)] or C-6 [by N-acetylgalactosamine 4-sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase (GalNAc4S6ST) [25] and uronyl 2 sulfotransferase (UST) [26] positions of GalNAc or at the C-2 position of IdoA [reaction catalyzed by DS 2-O-sulfotransferase (DS2ST)]. Due to the epimerization and sulfation reactions the structure of DS is heterogeneous [27-29].

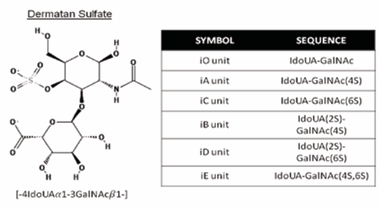

The variety in the DS structure is responsible for providing these disaccharide subtypes: IdoUA-GalNAc (iO), IdoUAGalNAc(4S) (iA), IdoUA-GalNAc(6S) (iC), IdoUA (2S)-GalNAc(4S) (iB), IdoUA(2S)-GalNAc(6S) (iD), and IdoUA-GalNAc(4S, 6S) (iE or H) (Figure 1). These molecules include a range of molecular weights, from 12 to 45 kDa, with an average of around 25 kDa [30-32].

Figure 1: Typical repeating disaccharide units of DS, and their sulfation positions. DS consists of IdoA and GalNAc disaccharides. These sugar moieties are esterified by sulfate at various positions, as indicated by 2S, 4S, and 6S, which represent 2-O-sulfate, 4-O-sulfate, and 6-O-sulfate, respectively. Abbreviations of possible disaccharide units are shown in the panel. The corresponding DS disaccharide units are indicated by ‘i’. Specific sequences composed of these units provide the structural diversity of DS, thereby affecting a wide range of interactions with various functional proteins or glycoproteins. The chemical structures were taken from the PubChem Substance and Compound database (pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The unique chemical structure identifiers are: 32756 (Dermatan, 4-(hydrogen sulfate)-Depositor: Chembase).

The ratio of IdoUA to GlcUA varies depending on the tissue source or the animal species from which the molecule was obtained [10,33,34,35,36], the stage of development [37-40], as well as the purification method. The IdoUA content of DS polymers may range from 1 to over 90%, even in many tissues from different animals and using different methodologies [41].

This sulfation pattern is responsible for a wide range of biological events involving DS, such as the assembly of extracellular matrices, the transduction of signals through binding to growth factors, wound healing, and anticoagulation; and studies have demonstrated a stimulatory effect on neurite outgrowth. Another important characteristic of the DS structure is the IdoA content, which can vary depending of each organ, developmental stage, or animal species used to obtain the molecule, among others [42-47].

For example, DS derived from porcine skin [48], marine clams [49], ascidians [50,51], the hagfish notochord [52], and sea urchins [53] is comprised of repeating disaccharide units with a high IdoA content (more than 80%) and the DS has both anticoagulant and neurite outgrowth activities [34]. In contrast, DS isolated from the horse aorta [54], embryonic pig brains [55], mouse brains [56], mouse skin [57], and HEK293 cells [58] has a low IdoA content, and can associate with growth factors such as pleiotrophin and midkine. These differences in the IdoA contents of DS chains are attributable to the levels of DS epimerases (DSepi1 and -epi2) in the Golgi apparatus of the cells comprising each animal species and tissues [59].

During development, IdoA-containing structures (iA, iB, iE, and iD) are ubiquitous in different parts of the brain [60], although at low concentrations. Indeed, DS in brains of newborn mice comprise only 2% iduronic acid [61-63]. The DS bioenzymatic machinery is carefully regulated during brain development, resulting in a large variation of IdoA-containing structures. For example, in the cerebellum, iD decreases and iB increases from newborn to adult age. Interestingly, embryo-derived DS shows a greater binding of fibroblast growth factor 2, 10, and 18 (FGF-2, 10, and 18), pleiotrophin, midkine, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) than DS from the brains of adult animals [64,65].

It was demonstrated that the rare oversulfated disaccharide units of iD present in embryonic pig brain-derived DS chains are critical elements for neuritogenesis [66,67]. In addition, the iE unit isolated from the hagfish notochord has a unique oversulfated structure characterized by a major disaccharide. Furthermore, exogenous iE exhibited appreciable inhibitory activity in midkine (MK)-mediated neuronal cell adhesion [52,68]. However, the presence of over sulfated iE structures in the mammalian brain has not been rigorously characterized [8,11].

One particularly well-studied DS binding interaction occurs with heparin cofactor II (HCII). This serpin homolog of antithrombin III acts by inhibiting the procoagulant effect of thrombin [69] This effect is enhanced 1000-fold in the presence of DS, characterized by the predominant disulfated disaccharide units of iB, which were shown to have high anticoagulant activity [70].

In fact, anti-inflammatory activity is among the most widely studied properties of DS glycosaminoglycans [73]. Furthermore, sulfated DS chains from marine sources have other important pharmacological activities such as antiviral, antiproliferative, tissue repair, and antitumoral activities [75,76]. These functions are attributed to the importance of the molecular size and some structural features required for biological activities, especially sulfate clusters to ensure interactions with cationic proteins [42,77,78,79].

Therefore, a number of marine based polysaccharides have been evaluated for their anti-inflammatory activity [81], as these eliminate the challenges and risks associated with molecules sourced from mammals [82]. Mammalian DS has been suggested as a potential alternative to heparin as it exhibits lower anticoagulant activity than heparin and therefore its use poses a smaller risk of hemorrhage [83]. DS with a variety of degrees and patterns of sulfation has been identified in the past in ascidians, but some of these polysaccharides have been shown to also have anticoagulant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-metatatic activities [50,51,69,84]

The reported functions of brain DS chains in neuritogenesis are controversial. DS acts as a neuritogenic molecule and also in modulating axonal growth, inhibiting or stimulating regeneration in an injured CNS. Such apparently contradictory functions are probably attributed to the structural diversity of DS chains [34,4455].

DS appears to modulate the development of neuronal polarity in vitro, favoring either axon or dendrite outgrowth from mesencephalic neurons [10]. In [85] the adult brain, DS is present in small amounts. It has been postulated that these changes in composition influence developmental events such as axonal elongation [44,67,86].

Due to the important role of DS in the CNS, the investigation of the molecular mechanisms in which this molecule is involved could lead to the future development of therapeutics in many neurodegenerative diseas.

The Gags of the central nervous system

Approximately 20% of the volume of the adult CNS is occupied by an extracellular space filled with proteins and polysaccharides that comprise the ECM of the CNS [87]. These GAGs are synthesized by both neurons and glia [88] and almost all of them have been detected in the intersticial extracellular matrix and in the specialized matrix surrounding some types of neuronal soma of brain tissue [89]. The main sulfated GAGs in the brain are CS and HS, which include different proteoglycans. DS and KS are found in small amounts in the adult nervous system. DS has variable production during development, but is found in high amounts in embryos [64,90]. In fact, radial glia are capable of producing hybrid CD/DS molecules in mammalian embryos [64]. Hyaluronan shares an interesting localization with CSPGs in perineuronal nets (PNNs) and heparin has not been described yet [89].

The interaction between these cells and their environment play an important and regulatory role in the CNS, even in the adult stage, but mainly in development, which evolves a series of specific steps, such as cell proliferation, neuron differentiation, neuron extension, axon outgrowth, synaptogenesis, and selective neuronal death, among others [90].

Many potentially important interactions also occur between cells and the neural ECM. Although the organization of the ECM in the vertebrate CNS is not well understood, it can be considered as a complex and dynamic association of extracellular molecules that is relatively rich in GAGs [36,91,92].

GAGs are found in PNNs, which are specialized ECMs that surround the soma, neurites, and axons in the initial segments of the neuron sub-population in the CNS [93,94]. PNNs are composed of CSPGs, hyaluronic acid, tenascin-R, and link proteins that coalesce to form molecular aggregates around neuronal cell bodies and processes [95]. The timing of PNN formation corresponds to the end of the critical period during which synaptogenesis, synaptic refinement, and maturation of the nervous system occur [96], suggesting that the formation of PNNs depends on completion or fixation of a plasticity change in neural activity [97].

Enzymatic disruption of PNNs by chondroitinase ABC treatment reactivates neural plasticity in the adult cerebral cortex after the critical period has ended, suggesting that the formation of PNNs restricts neural plasticity in the adult brain [98]. In several regions of the brain, including the cerebral cortex, PNNs are selectively formed around inhibitory interneurons. However, PNNs contain different GAGs depending on the region of brain. These GAGs were reported to interact with parvalbumin, which is implicated in the regulation of the critical period for plasticity after birth [99-101].

Distribution of DS in the nervous system

DS plays crucial roles in various biological events, such as the development of the CNS [64], wound healing [27,42], growth factor signaling [21,102], and proliferation of a neural stem cell progenitor. Among these events, the involvement of DS in the development of the CNS has attracted attention from a therapeutic point of view due to the potential application of DS to nerve regeneration [103]. Several studies have shown that the sulfation pattern of DS in the brain alters during development, characterized by an increase in 4-O-sulfation and a decrease in 6-O-sulfation [104-107]. In addition, both the increase in 6-O-sulfation disaccharides and the presence of IdoA have been shown to be crucial factors for the neurite growth-promoting activity of DS [34,91,108,109]. This type of DS is found in high amounts during the development of the mammalian CNS, synthesized by both neurons and glial cells (oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and microgliocytes), which are crucial for its development as well as for its homeostasis [110,111].

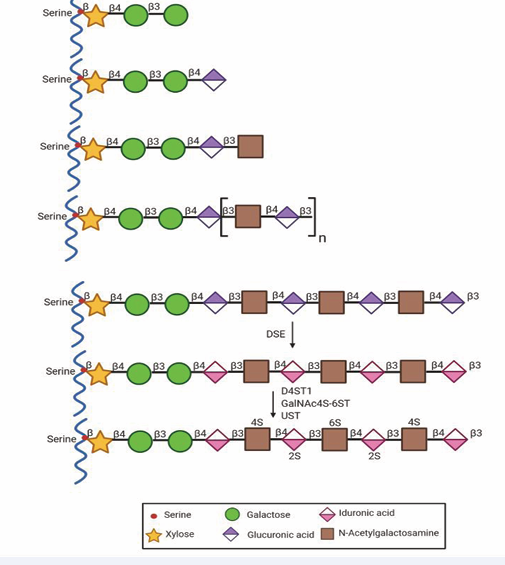

The importance of DS in CNS development was better elucidated with results of an analysis of DS-epi2-deficient mice. DS epimerases convert GlcA to IdoA by catalyzing the C5- epimerization of GlcA residues, which is the initial modifying step in the biosynthesis of IdoA-containing structures in DS [93,112]. Intriguingly, the loss of C5 epimerase using the DS-epi2-deficient mouse model presented a primarily normal brain phenotype, but showed a drastic reduction in IdoA levels compared to wild-type littermates. Further analysis revealed a significant decrease in 4-O-sulfate and an increase in 6-O-sulfate expression [113,114]. The apparent normal phenotype of the brain that was observed in the adult DS-epi2-deficient animals suggests a possible compensatory mechanism, possibly through DS-epi1 expression. These results support the hypothesis that there are functional redundancies in the role of DS in the ECM (Figure 3; [63].

The DS bioenzymatic machinery is carefully regulated during brain development, resulting in a large variation of IdoAcontaining structures. The proportion of iE units is very small compared with that of iB or iD units in DS from all regions of the postnatal brain. However, unlike in the cerebellum, iD decreases and iB increases from newborn to adult age, but in the adult mouse brain the iD structure is still observed in the cortex, thalamus, cerebellum, and prominent in the hippocampus, a region of constant neuritogenesis [56].

An in situ analysis of the DS in brain sections revealed that the concentration of DS increases 2-fold during development (from postnatal day 7 to postnatal week 7). The proportions of DSspecific main disaccharides iA and iB produced by the sequential actions of D4ST-1 and single uronyl 2-O-sulfotransferase (UST) preferentially catalyzed the 2-O-sulfation of IdoUA in iA units, forming another DS-specific iB unit, in which 2S and 4S representing the 2-O- and 4-O-sulfate groups, respectively, were higher in the DS chains from the other brain regions.

A dramatic increase (10-fold) in the proportion of iB occurs during development, and in contrast, iD and iE decrease to 50 and 30%, respectively, in the developing cerebellum. These results suggest that the IdoUA-containing iA and iB units along with the iD and iE units in the DS play important roles in the formation of the cerebellar neural network during postnatal brain development [115,116].

Therefore, characteristically functional DS chains may be distributed in the brain parenchyma, where the neural network forms during development. However, the spatiotemporal distribution of such IdoUA-containing DS structures in the brain remains largely unknown because of analytical difficulties.

Involvement of Ds in Neuritogenesis

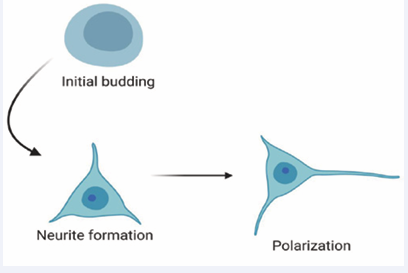

Neuritogenesis is an early event in neuronal development in which newborn neurons first form growth cones, as a prerequisite for the formation of axons and dendrites. Growth cones emerge from segmented regions of the lamellipodium of embryonic neurons and grow away from the cell body, leaving behind a neurite that will eventually polarize into an axon or dendrite [93]. Growth cones also navigate precise routes through the embryo to locate an appropriate synaptic partner [118]. Dynamic interactions between two components of the neuronal cytoskeleton, actin filaments and microtubules, are known to be essential for growth cone formation and hence neuritogenesis (Figure 2). The molecular mechanisms that coordinate interactions between actin filaments and dynamic microtubules during neuritogenesis are beginning to be understood [94,119].

Figure 2: Schematic representation of the steps involved in the process of neurite establishment.

Although CNS regenerative capacity is limited in adulthood, the CNS is a rich and complex source of DS, including during development and under pathological [120,121]. The heterogeneity of the DS structure may be promising as a regulator of bioactive proteins interacting with soluble and membrane-associated molecules [122]. The observed potential of DS to promote neuritogenesis in vitro, using primary cultures of neurons or cell lineage as models (Table 1), is important not only to show its role in the natural process of CNS development but also its role in neural diseases.

| Table 1: The observed potential of DS to promote neuritogenesis in different study models. | |||||

| SPECIFIC DS MOTIEF | IN VITRO MODEL | SOURCE | ORIGIN | EFFECT | REF. |

| iD units | E16 mouse hippocampal neurons | Ascidian P. nigra | Soma | Neurite growth | Hikino et al., 2003 |

| iD units | Embryonic mouse hippocampal neurons | Embryonic pig brains | Soma | Binding growth factor pleiotrophin | Bao et al., 2005a |

| iD units | E16 mouse hippocampal neurons | Shark skin | Soma | Neuritogenic activity | Nandini et al., 2005 |

| iD units | E14 rat mesencephalic neurons and E18 rat hippocampal neurons | Postnatal mouse brain | Soma | Neurite growth | Faissner et al., 1994 |

| iD units | E14 rat post-mitotic mesencephalic neurons | Bovine mucosa | Soma | Neurite growth | Lafont et al., 1992 |

| iE units | E16 mouse hippocampal neurons | Embryonic sea urchin | Soma | Neurite growth | Hikino et al., 2003 |

| iB units | E16 mouse hippocampal neurons | Ascidian S. plicata | Soma | Neurite growth | Hikino et al., 2003 |

| iB units | E16 mouse hippocampal neurons | Porcine skin | Soma | Neurite growth | Hikino et al., 2003 |

| iE units | E16 mouse hippocampal neurons | Hagfish notochord | Soma | Neurite growth | Hikino et al., 2003 |

| CS-DS | E16 mice hippocampal neurons | Shark Isurus oxyrinchus and Prionace glauca | Soma | Neurite growth and midkine and pleiotrophin interact strongly | Higashi et al., 2015 |

| CS-DS | E18 rat hippocampal neurons | Hagfish notochord | Soma | Neurite growth | Nandini et al., 2004 |

| DS | Chst14-deficient mice - Axon Axonal growth Akyüz et al., 2013 DS Chst14-defici | - | Axon | Axonal growth | Akyüz et al., 2013 |

| DS | Chst14-deficient zebrafish | - | Axon | Axonal growth | Sahu et al., 2019 |

| DS | Neuro-2A cell lineage | Ascidian P. nigra | Soma | Neurite outgrowth neuroprotector, antioxidant | de Sousa et al., 2020 |

It also stimulates future studies aiming to directly test the therapeutic effect of DS in experimental designs using animal models of neural lesions. This would make it possible to evaluate the real beneficial effect of DS in CNS repair, evaluating which mechanisms are involved, which could be of great interest for regenerative medicine [6,44,49].

Figure 3: Biosynthesis of DS. CS and DS share the synthesis of a tetrasaccharide linker region that attaches the GAG chains to a serine residue within the conserved attachment site of core proteins. The activity of a unique N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-I that transfers the first GalNAc residue onto the tetrasaccharide linker starts a growing glycosaminoglycan chain to CS. This step is followed by the activities of specific enzymes that polymerize the glycosaminoglycan chain by the alternate additions of N-acetyl-D-galactosamine and D-glucuronic acid moieties in CS. CS chains can be modified during elongation by Golgi residents, epimerase, and a number of sulfotransferases. After the formation of the chondroitin backbone, epimerization of GlcUA to L-iduronicacid by C5-hydroxyl epimerases (DSE) followed by sulfate addition to the C4 hydroxy of the adjacent GalNAc residue by D4ST1 generates DS from CS and prevents back-epimerization of IdoUA to GlcUA. The extent of modification with sulfate groups by the actions of CS and DS sulfotransferases varies between different core proteins, and spatio-temporally.

[34] assessed neurite outgrowth-promoting activities of DS variants in cultured E16 mouse hippocampal neurons and investigated the involvement of IdoUA-containing DS-type structures in neuritogenic properties. Porcine skin DS, which contains iB units, was not neuritogenic, however DS purified from neonatal mouse brains, containing a small proportion of iD units, exhibits small neurite outgrowth activity.

[56] isolated iD units (Table 1) from embryonic pig brains and analyzed the promotion of outgrowth neurites in embryonic mouse hippocampal neurons in cultures, which showed neuritogenic activity revealed by interaction with the growth factor pleiotrophin (PTN).

Many marine animals show large amounts of DS with a different structure. For example, the iE structure is a major disaccharide found in DS from the hagfish notochord (68%) and embryonic sea urchins (74%), while a significant amount of iD units is found in ascidian Phallusia nigra DS (~80%) [50]. Interestingly, a high amount of iB disaccharide is also found in DS from the ascidian Styela plicata (66%). In addition, DS obtained from the species of elasmobranchs Isurus oxyrinchus and Prionace glauca contains levels of IdoA disaccharides and iB, iC, and iD units [123]. These different DS structures have been used to better comprehend the neuritogenesis activity and the function of DS in the brain and all of them showed this activity, but with some peculiarities.

Neuritogenic activity was observed using DS from the S .plicata ascidian, which contains a small proportion (5%) of iD units, and with DS from hagfish (68%) [34]. However, in a comparison between DS from S. plicata and from P. nigra, significant neurite outgrowth-promoting activity was observed using P. nigra, which resulted in specific morphological features. The P. nigra DS, which contains a high amount of iD structure (60%), induced a flattened neuronal cell soma and multiple dendrite-like neurites. On the other hand, S. plicata DS exhibited only modest neurite outgrowth-promoting activity [34,55].

In a recent study, our research group showed a clear in vitro neuroprotective and antioxidant effect of the DS from tissues of P. nigra ascidia (PnDS), using the neuro-2A cell lineage subjected to cytotoxic damage by the pesticide rotenone [124]. Cell damage by rotenone is used as a model for neurodegeneration and oxidant damage (for a review, see [125]. It was also shown that PnDS promoted an evident increase in neurite length, mainly in undamaged cells. In addition, PnDS showed neuroprotective action even in neurons exposed to rotenone, diminishing the percentage of cells stained with iodite propidium, which indicates cell death. The antioxidant properties of PnDS were analyzed and indicated a significant decrease in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) induced by rotenone [124].

Embryonic sea urchins, which have 74% iE DS units, induced the longest neurites in a hippocampus neuronal culture in comparison with ascidian DS. However, the effects on the soma area and number of primary neurites/cells were best observed with P. nigra DS [34].

Many studies suggest that DS is responsible for the effect on neurons and this aspect appears to be dependent on DS interaction with a particular neuron phenotype. Multiple DS units exhibited the promotion of outgrowth of neurites of both an axonic and a dendritic nature, characteristic in the embryonic brains cultured [10,36,109].

In the CNS, it is known that DS interacts with growth factors and neurotrophic factors in the neural process, axon orientation, and neurite outgrowth [64], promoting axon growth [126], neural migration, and neuritogenesis [67], apparently regulating the differentiation and proliferation of neuronal cells. In this process, the sulfation patterns of DS chains appear to directly influence the binding of the active proteins [21].

[127] analyzed neuronal differentiation in murine embryonic stem cell culture (mESCs) and human neural stem cells (hNSCs) cultures containing DS. In mESCs, DS promoted neuronal differentiation by activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and also accelerated neurite outgrowth. In hNSCs, DS promoted neuronal differentiation and neuronal migration, but not neurite outgrowth.

The specific arrangement of the sulfation patterns of CS-DS chains is known to modulate various signaling pathways such as wingless/int-3a (Wnt-3a) involved in many developmental and disease-related processes to regulate cellular differentiation and proliferation of nearby cells in surrounding tissues. The loss of the wingless (Wg) activity in chlorate-treated cells is most likely due to the specific effect of blocking GAG sulfation on these cells, since supplying sulfated GAGs restores activity. Together, these results suggest that sulfated GAGs can play an important role in promoting WG signaling [128,129].

Class III semaphorins (SEMA3s) binding to CS-E (GalNAc(4,6- SO4 ) units) in the PNNs restrict growth and plasticity and influence a wide range of molecules and cell types inside and surrounding that injured tissue [130-132] and in family receptor protein tyrosine phosphatases (RPTPs) expressed by both neurons and glia, implicated in synaptogenesis and axon pathfinding during development, and post-injury axonal plasticity [134]. Chondroitinase ABC digestion of the CS and DS side chains reduce binding to these receptors; and the Nogo receptor (NgR) family members NgR1 and NgR3 bind with high-affinity to monosulfated CS-B (DS) and participate in chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan (CSPG) inhibition in cultured neurons [136-138].

[139] generated deficiency in mice of dermatan 4-O-sulfotransferase1 (Chst14), a key enzyme in the synthesis of iduronic acid-containing modules found in DS but not CS. In wildtype mice, Chst14 is expressed at high levels in the skin and in the nervous system and is enriched in astrocytes and schwann cells. Ablation of Chst14, and the assumed failure to produce DS, resulted in enhanced axonal growth of CNS neurons as well as schwann cell process formation and proliferation in vitro.

It has been reported that Chst14 specific to DS, but not chondroitin 4-O-sulfotransferase-1 (Chst11) specific to CS, regulates proliferation and neurogenesis of neural stem cells (NSCs), indicating that CS and DS 4 sulfated play distinct roles in the self-renewal and differentiation of NSCs. The protein levels of N-MethylD-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5- methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor, postsynaptic density 95 (PSD95), growth associated protein 43 (GAP-43), synaptophysin (SYN), and N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor (NSF), which are important in synaptic plasticity, were examined and Chst14 deficiency was observed. The results showed a significant reduction in the expression of these proteins in the hippocampus. Further studies revealed that protein kinase B (Akt)/mammalian target rapamycin (mTOR) was implicated in the cell death and cognitive outcome after cerebral contusion in mice, and some intracellular proteins including Akt and mTOR were significantly lower in Chst14−/− mice, which might contribute to decreased protein expression [140].

In conclusion, all these previous studies demonstrated an important role of DS not only in neuritogenesis but as a neuroprotector and antioxidant molecule. These results might trigger new in-depth studies into the role of DS in healthy and diseased brains.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

GAGs have been shown to have important involvement in the development and regeneration of animal tissues [122]. Moreover, GAGs have been used as drugs for various types of diseases, such as HP [141], CS [142], and HA [143], sometimes with contradictory evidence about their efficacy. For instance, CS has been used in oral administration, but its efficacy has not yet been scientifically demonstrated [142]. The anticoagulant effect of HP has been used in medicine since the 1930s, but there are still questions about its safety [141]. Experimental evidence of the role of DS in neuroregeneration may be sufficient to stimulate future preclinical studies and clinical trials. However, several points may still depend on further experimental research to define important aspects before DS can be considered as a drug for brain diseases, such as the route of administration, a reliable source, and the purification technique.

Considering the clinical application of DS, it has to be pointed out that all demonstrations of the effect of DS in neuritogenesis have come from in vitro studies Table 1, [122]. Experiments using animals, especially mammals, are imperative to evaluate the possibility of obtaining the beneficial biological effect of DS in the CNS, and to test important technical aspects, such as the route of administration and form of dosage. Regarding the effect of DS in other physiological systems, besides in vitro studies, in vivo studies have demonstrated the beneficial anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic, and anti-metastatic activities of ascidian DS after intravenous and subcutaneous administration in mice [69,84]. Future studies using in vivo models and chemical digestion with specific enzymes are needed to reveal the real clinical potential of DS to treat CNS diseases.

Another important aspect is the source of DS to be applied as a drug. GAGs are obtained from mammalian tissues. For instance, HP has been commercially obtained from bovine and porcine tissues. The source of GAGs is natural products, since they are not currently chemically synthesized [122]. Beside terrestrial animals, marine animals are also an important source of GAGs, including DS [78,122]. Some marine DS is oversulfated, sharing similarities with embryonic mammalian DS and having enhanced neuritogenic activity [78,122]. DS obtained from marine organisms might be used as a potential source for preclinical and clinical in vivo studies about CNS diseases.

A potential drug to act inside the CNS has to be able to cross the blood brain barrier (BBB). Further studies about the ability of DS or its derivatives enzymatically digested to small oligosaccharides capable of crossing the BBB and which preserve neuroprotective properties are needed using in vivo models. The combination of DS with different types of vehicles, such as nanoparticles, for example, could be evaluated to widen the pool of possibilities for using DS oligosaccharides as a drug with the expected biological effect inside the CNS. This protocol was used in an in vivo model and showed anti-inflammatory activity in a rat paw edema model [144].

In light of the information contained in this review, the characterization of the minimal structures of neuroactive DS chains is important to elucidate their mechanism for promoting neuritogenesis. Here, it was possible to observe that DS can be found in some neurogenic regions such as the hippocampus to aid in the formation of new neurons. Therefore, DS is a promising candidate for developing drugs that aim to regenerate neurons and treat neurodegenerative disease.

SUPPORT

This work was supported by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), the Institute of Biodiversity and Sustainability (NUPEM), and through Young Scientists of the New State grant number E-26/203.021/2018 and the Rio Network of Innovation in Nanosystems for Health - Nanohealth/FAPERJ (E-26/010.000983/2019) of the Research Support Foundation of the State of Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ).