Applicability of Structural Equation Modeling In Practice of Optimal Dietary Intake amongst Recuperating Alcoholics

- 1. Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, Kenya

Abstract

Background: Structural equation modeling is a methodology for representing, estimating, and testing a network of relationships between measured variables and latent constructs. This statistical approach is used quite readily to test theoretical models and provide overall fit indices that determine whether the model tested actually fits the observed data.

Objective: We aimed at providing recuperating alcoholics with the basics of structural equation modeling so they can assimilate evidence from studies that use this statistical tool to incorporate such findings into optimal dietary intake practice.

Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted from August to November 2018 amongst recuperating alcoholics receiving rehabilitation in Asumbi treatment center of Homabay County, Kenya. Structural equation modeling determined the evidence of practice of optimal dietary intake amongst recuperating alcoholics.

Results: Structural model parameter estimation showed high values, especially for subjective norm (β=0.62, p<0.01, n=207) that significantly influenced practice of optimal dietary intake.

Conclusion: Nutritionist or other health professionals who wish to use SEM to explore such relations should apply all the steps used in SEM and ensure they have a sample that is sufficient.

Keywords

- Dietary intake

- Alcoholics

- ANOVA

- Structural equation modeling

Citation

Mutuli LA, Bukhala P (2020) Applicability of Structural Equation Modeling In Practice of Optimal Dietary Intake amongst Recuperating Alcoholics. J Hum Nutr Food Sci 8(1): 1134.

INTRODUCTION

Alcoholism and practice of optimal dietary intake uses a variety of well-reasoned conceptual models to explain a number of phenomena [1,2]. Although conceptual models help to propel research, it is often difficult to test such models with conventional statistical approaches such as t-tests, analysis of variance (ANOVA), multiple regressions, and chi-squared. One statistical approach that clearly stands out as an obvious choice for testing conceptual models is structural equation modeling (SEM). Structural equation modeling is a widely recognized statistical technique in validating a hypothetical model about relationships among variables. It also provides a structure to analyze relationships between observed and latent variables, and allows causal inference. Its popularity has recently increased in many applications, including medical, health, biological and social sciences [3,4]. One of the main reasons of increasing popularity of SEM is that it provides concise assessment of complex model involving many linear equations. In general, SEM is a technique for multivariate data analysis, and involves a combination of two commonly used statistical techniques [5]: factor analysis and regression analysis. Currently, many journals publish multivariate analysis of data using SEM. In most cases, the model needs to be re-specified based on the values of the goodness-of-fit criteria of the initially formulated model [6]. SEM can be an effective tool to depict relationships between practice of optimal dietary intake and alcoholism, and the associated factors. There are many factors associated with practice of optimal dietary intake of recuperating alcoholics, including nutrition knowledge, economic status, food security, gender and culture [7,8]. Although information on these variables is readily available in many studies, the response variables are often not directly measurable but are latent, with the observed variables being their manifestations [9,10]. In this study, we investigate the influence of attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control variables on practice of optimal dietary intake amongst recuperating alcoholics. We consider the structural equation modeling for this purpose, which is a powerful statistical tool for causal inference among the observed and latent variables.

METHODS

Study Area and Design

Asumbi-Homabay located in Homabay County, Nyanza region of Kenya formed the study area mainly because of the existence of Asumbi rehabilitation center. This center was purposively sampled with the target that it receives numerous alcoholic patients both males and females from different parts of the country, offers standardized rehabilitation services to alcoholic rehabilitees and it’s accredited by NACADA. This cross-sectional study was conducted from August to November 2018 amongst recuperating alcoholics receiving rehabilitation in Asumbi treatment center of Homabay County, Kenya. Permission was obtained from the School of Graduate Studies. Ethical approval was given by National Council for Science and Technology. We sought informed consent from the respondents who were informed on the research procedures, details, and assured of confidentiality.

Sampling Techniques and Criteria

Purposive sampling technique was used to select Asumbi rehabilitation center as the study site because it’s the only rehabilitation center that admits and rehabilitates exclusively alcoholics. Stratified sampling was used to select 207 respondents from each stratum (males and females). A sample of 129 respondents from the male stratum and 78 respondents from the female stratum was developed.

Inclusion criteria included:

- Female and male alcoholics aged 15-65 years who were admitted not more than a week prior to start of the study and those who voluntarily consented to participate in the study.

- Alcoholics exclusively suffering from alcoholism and not other addictive substances

Exclusion criteria included:

- Alcoholics with active psychotic symptoms were excluded.

- Alcoholics not intending to complete the three months of rehabilitation in Asumbi center were not inclusive.

Data Collection Instrument and Procedure

A questionnaire with a seven point Likert scale was constructed along a continuum range from totally disagree/not all/extremely unlikely=1 to totally agree/ very much /extremely likely=7 was used to measure all the variables. Higher scores indicated more positive attitude towards practice of dietary intake in alcohol rehabilitation. A 7-point scale, with end points of (7) and (1) was used to elicit the alcoholic’s beliefs about significant referents’ expectations on practice of dietary intake during alcohol rehabilitation. Another set of 7-point scales evaluated alcoholic’s motivation to comply with significant others’ expectations and was contained in end points (1) not at all and (7) very much. Three items with 7-point response scales elicited the alcoholics’ perceptions on dietary intake in alcohol rehabilitation. The anchors were extremely likely (7) to extremely unlikely (1). One additional item measured perceptions of confidence in ability on a 7-point scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) strongly agree (7). Scores were summed and divided by the number of items for a possible mean score of 1 to 6.5; higher scores reflected greater perceived control. Dietary intake intention was measured with one 7-point scale, containing end points of strongly disagree (1) and strongly agree (7). The midpoint of the scale represented unsure practice of dietary intake during alcohol rehabilitation. To establish validity, the questionnaire was given to two experts to evaluate the relevance of each item in the instrument to the objectives (content validity). The experts appraised what appeared to be valid for the content, the test attempted to measure (face validity). The degree to which a test measured a sufficient sample of total content that was purported to measure was considered (sampling validity). The questionnaire was administered on respondents and the interview responses filled in by the researcher to gather information on the influence of attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral on practice of optimal dietary intake during alcohol rehabilitation. The respondents were then interviewed through previous booked appointments and each interview lasted for a maximum of 1 hour.

Data Analysis

Data was entered into SPSS version 15 to calculate reliability tests where Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the consistency of the questions. Structural Equation Modelling using AMOS version 7 was used to determine the influence of attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioural control on practice of dietary intake during the rehabilitation of alcoholics. The overall model fit was evaluated using chi-square (CMIN) and relative chisquare divided by degrees of freedom (CMIN/df), comparative fit index (CFI), the standardized root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), Hoelter’s critical N, and Bollestine bootstrap. Comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker Lewis index (TLI), values greater than 0.90 were considered satisfactory [11]. RMSEA less than 0.08 was also considered satisfactory [12]. CMIN/df was considered fit when it ranged between 3:1 and was considered more better when closer but not less than 1 [13]. Hoelter’s critical N for significance level of .05 and .01 was used where bootstrap samples was set at 200 [14].

RESULTS

Structural Equation Modeling applied to Optimal Dietary Intake

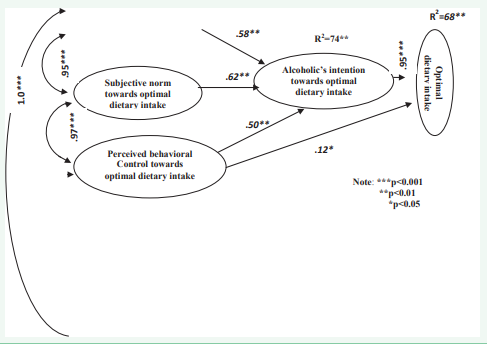

Structural equation modeling was used to establish whether a model nested based on Theory of Planned Behavior variables applied on optimal dietary intake fits the data acceptably well. To answer the research questions, it was essential to base the measurement model on the original concepts of this theory. Both item measurement analysis and measurement model analysis were performed using observed and unobserved variables in attempt to assess the extent to which the model fits the data. These variables are presented in (Table 1) and displayed in a measurement model (Figure 1).

|

Table 1: Endogenous and Exogenous variables of the Measurement Model. |

|

|

Endogenous Variables |

Exogenous Variables |

|

Observed |

Attitude |

|

Attitude-1 (A1) |

e4 |

|

Attitude-2 (A2) |

e3 |

|

Attitude-3 (A3) |

e2 |

|

Subjective-1(SN1) |

Subjective Norm |

|

Subjective-2 (SN2) |

e8 |

|

Subjective-3 (SN3) |

e7 |

|

Perceived behavioral control-1(PBC1) |

e5 |

|

Perceived behavioral control-2(PBC2) |

Perceived behavioral control |

|

Perceived Behavioral Control-3(PBC3) |

e12 |

|

Intention-1(I1) |

e10 |

|

Intention-2(I2) |

e9 |

|

Intention-3(I3) |

e13 |

|

Dietary intake-1 |

e15 |

|

Dietary intake-2 |

e16 |

|

Dietary intake-3 |

e20 |

|

Unobserved |

e18 |

|

Intention |

e17 |

|

Optimal dietary intake |

Other-1 |

|

Other-2 |

|

|

Note: e=error; other= residual; 1=eating variety of foods; 2=nutrient adequacy; 3=eating balanced diets |

|

Figure 1: Default Model.

All the measures were subjected to skewness test based on the recommended range ±2 for normal distribution [15]. The critical ratio represents skewness (or kurtosis) divided by the standard error of skewness (or kurtosis). It is interpreted as one would interpret a z-score. Values greater than 2, 2.5 or 3 are often used to indicate statistically significant skew or kurtosis (Table 2). In this study items presented positive skew and all measures of optimal dietary intake were normally distributed.

|

Table 2: Assessment of Multivariate Normality of the Measurement Model. |

||||||

|

variable |

minimum |

maximum |

skewness |

critical ratio |

kurtosis |

critical ratio |

|

D3 |

1.00 |

7.00 |

2.42 |

2.60 |

2.93 |

3.19 |

|

D2 |

1.00 |

7.00 |

2.00 |

2.21 |

2.78 |

2.88 |

|

D1 |

1.00 |

7.00 |

2.62 |

2.20 |

2.18 |

2.77 |

|

PC1 |

2.00 |

6.00 |

2.41 |

2.53 |

3.48 |

2.50 |

|

PC2 |

4.00 |

7.00 |

2.45 |

2.71 |

2.98 |

3.05 |

|

PC3 |

3.00 |

6.00 |

2.55 |

3.45 |

3.99 |

2.08 |

|

SN1 |

2.00 |

4.00 |

2.58 |

2.59 |

2.96 |

3.00 |

|

SN2 |

3.00 |

8.00 |

2.82 |

2.10 |

3.04 |

3.24 |

|

SN3 |

2.00 |

9.00 |

2.96 |

2.98 |

3.52 |

2.61 |

|

I1 |

2.00 |

7.00 |

2.80 |

3.48 |

2.54 |

3.79 |

|

I2 |

1.00 |

7.00 |

2.40 |

2.50 |

2.79 |

3.45 |

|

I3 |

1.00 |

7.00 |

2.89 |

3.54 |

2.52 |

3.62 |

|

A1 |

2.00 |

8.00 |

2.59 |

3.21 |

2.66 |

3.19 |

|

A2 |

3.00 |

6.00 |

2.85 |

2.55 |

2.87 |

2.77 |

|

A3 |

2.00 |

5.00 |

2.65 |

2.56 |

2.90 |

2.32 |

|

Multivariate |

|

|

|

|

44.28 |

39.18 |

|

Note: 1=eating variety of foods; 2=diet adequacy; 3=eating balanced diets D=Optimal dietary intake; PC=perceived behavioral control; SN=subjective norm; A=Attitude; I=Intention |

||||||

Model Fitness

The covariance matrix estimated by the model did not adequately reproduce the sample covariance matrix model. To adjust a model, new pathway was added. The parameter changed from fixed to free. The common procedure used for model modification was the Lagrange Multiplier Index. This test reported the change in chi-square value when pathway is adjusted. Model modification involved adjusting the specified and estimated model by either freeing parameters that were fixed or fixing parameters that were free. The Lagrange multiplier test provided information about the amount of chi-square change that resulted in fixed parameters that were freed. In this study the goodness of fit was statistically non-significant at the .01 level but the model would be rejected at the .05 level (χ²=224, df=82, p=0.14, χ²/df =2.73). Although the chi-square was under the recommended 3:1 range, acceptable fit was obtained after modification indices were done. Fit indices summarized in (Table 3) (TLI = .93, CFI =.95, RMSEA= 0.090) also demonstrated goodness of fit for the measurement model.

|

Table 3: Fit Indices of Default Model. |

||

|

Fit Indices |

Recommended fit Measures |

Default Measures |

|

RMSEA |

0.09 or less is better |

0.09 |

|

CFI |

above 0.9 is good fit |

0.95 |

|

CMIN/DF |

between 2-3 |

2.20 |

|

TLI > |

0.8 is good fit |

0.93 |

|

Hoelter’s Critical N> |

200 adequate |

207 |

|

p > |

0.10 good fit |

0.14 |

|

Note: RMSEA=Root mean square residual; CFI=Comparative fit index; CMIN/DF=Chi-square/degree of freedom; TLI= Tucker-Lewis Index; χ²= Chi-square |

||

Hoelter’s critical N values recommend that the model would have been accepted for lower limit at the .05 significance level with 200 cases and the upper limit of N for the .01 significance level is 207 cases.

Structural Equation Models

The overall modelling analysis exhibited three types of outputs namely; saturated, default and independent model. The saturated model is insignificant but fully explanatory model in which there are as many parameter estimates as degrees of freedom. Most goodness of fit measures will be 1.0 for a saturated model, but since saturated models are the most un-parsimonious models possible, parsimony-based goodness of fit measures will be 0. Some measures, like RMSEA, cannot be computed for the saturated model at all. The independence model is one which assumes all relationships among measured variables are 0. This implies the correlations among the latent variables are also 0. Where the saturated model will have a parsimony ratio of 0, the independence model has a parsimony ratio of 1. Most fit indexes will be 0, whether of the parsimony-adjusted variety or not, but some will have non-zero values (RMSEA, GFI) depending on the data. The default model (Figure 1) is the researcher’s structural model, always more parsimonious than the saturated model and almost always fitting better than the independence model with which it is compared using goodness of fit measures. That is, the default model (Figure 1) will have a goodness of fit between the perfect explanation of the trivial saturated model and terrible explanatory power of the independence model, which assumes no relationships.

The default model was estimated with five latent variables and paths. As shown in (table 3) the default model’s chi-square value was not significant at 0.05 significance level (χ²=224, df=82, p=0.14, χ²/df=2.73) and all other indices indicated that the default model was acceptable (RMSEA=.090, CFI=0.95, CMIN/DF= 2.73, TLI=0.93) and Hoelter’s critical N= 207. The default model explained 74 percent of variance for optimal dietary intake intention and 68 percent of variance for optimal dietary intake. Standardized regression weights in (Figure, 1), indicates that subjective norm (β=0.62, p0.05, n=207). Intention in turn strongly predicted optimal dietary intake (β=0.95 p<0.001, n=207). The correlation between attitude and perceived behavioral control was statistically significant (β=1.00 p<0.001, n=207). This was followed by the correlation between subjective norm and perceived behavioral control (β=.97 p<0.001, n=207) which was statistically significant. The correlation between attitude and subjective norm was also statistically significant (β=.95 p<0.001, n=207). Intention predictors (attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control) put together accounted for 74 percent of the variance on optimal dietary intake intention. Optimal dietary intake intention and direct perceived behavioral control put together accounted for 68 percent of variance on optimal dietary intake.

DISCUSSION

This study provides an empirical example of how SEM can be used to explore complex relations between practice of optimal dietary intake and associated factors amongst recuperating alcoholics. The study reports that attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control put together accounted for 74 percent of the variance on optimal dietary intake intention. The strength of these correlations indicated that associations were meaningful and represented important targets for optimal dietary intake. Optimal dietary intake intention and direct perceived behavioural control put together accounted for 68 percent of variance on optimal dietary intake. Conversely, [16] previously reported no association between intention and healthy eating behavior (β=0.05 p>0.001, n=139). However, healthy eating behavior was correlated with attitude (0.44), perceived behavioral control (0.35), and subjective norm (0.34). The lack of association between intention and healthy eating might be explained by the concept of intention instability suggesting that factors other than intentions may influence healthy eating behaviors. [17] found that intentions were stronger predictors of optimal dietary intake when intentions were stable in adults eating a low-fat diet. Recently, [18] in a systematic review of 22 relevant studies reported significant relationship between intention and behavior of close to1, and the variance on behavior was statistically considerate [19] examination of the association of TPB variables and dietary patterns, reported attitudes as strongest association with intention (r+ = 0.61) followed by perceived behavioral control (PBC, r+ = 0.46) and subjective norm (r+ = 0.35). The association between intention and behavior was r+ = 0.47, and between PBC and behavior was r+ = 0.32. These associations were robust to the influence of key moderators. However, analyses revealed that younger participants had stronger PBC-behavior associations than older participants. This finding implies that although associations were robust to the impact of moderators, the key associations between PBC, intention and behavior were found to differ significantly based on variables with important practical and methodological implication. This has valuable implications to health professionals particularly nutritionists in rehabilitation centers who are involved with the rehabilitation of alcoholics. This further has important implications for the design and interpretation of future studies that aim to inform programmatic and policy decisions with regard to dietary intake of recuperating alcoholics. [20] emphasized that to develop interventions that can impact on promoting optimal dietary intake it’s compulsory to control for several food choice behaviors, which only be conducted with use of SEM. To benefit from articles that use this approach, health professional do not need to know everything about SEM. However, it is important that health professionals particularly nutritionists to keep the following points in mind as they read the literature. First, the hypothesized model tested by SEM must be based on some combination of theory and findings in the literature. Second, SEM is strong if it has latent variables that are measured by multiple indicators. Third, only the significant paths in the model are considered important if the RMSEA is 0.10 or lower. Other than that, there are many complexities of SEM that warrant discussion but are beyond the scope of this introductory paper.

CONCLUSION

The use of SEM, although still applied sparsely in nutritional sciences, has the potential to expand knowledge of complex relations among social and behavioral constructs and measured variables. Nutritionist or other health professionals who wish to use SEM to explore such relations should apply all the steps used in SEM and ensure they have a sample that is sufficient. These steps may help to ensure a more accurate depiction of relations among the variables to more appropriately inform the translation of findings to nutrition-related policies and programs. The researchers should also under the weakness that hinder use of SEM and appreciate the strength associated with it.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that no conflict of interests exists.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved with the drafting of the research paper, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version submitted for publication.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors sincerely thank participants who shared their experiences, and contributed needed information to the study. All those contributed to the success of this study in one way or another are also recognized

REFERENCES

3. Kline RB. Principle and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. The Guilford Press. 2011.

7. Munro B. Statistical Methods for Health Care Research,5th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.Polit D, Beck C (2004) Nursing Research: Principles and Methods, 7th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. 2005.

11. Garson GD. Structural equation modeling. 2009.

14. Weston R, Gore P. A brief guide to structural equation modeling. Counsel Psychol. 2006; 34: 719-151.

15. Mardia KV, Kent JT, Sussman S, Bibby JM. Hypothesis Testing. In Birnbaum,Z. (ed.), Multivariate Analysis. Academic Press, New York. 1974; 123-124.

16. Read JP, Kahler CW, Stevenson JF. Bridging the gap between Alcoholism treatment Research and Practice: Identifying what works and why. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2011; 32: 227-238.