Breaking Breakfast Habits: Strategies for Healthier and More Sustainable Breakfast Habits

- 1. Wageningen Food and Biobased Research, Wageningen University and Research, The Netherlands

- 2. Unilever Foods Innovation Centre Wageningen, The Netherlands

- 3. Human Nutrition & Health, Wageningen University and Research, The Netherlands

- 4. University of Utrecht, Applied Cognitive Psychology, The Netherlands

Abstract

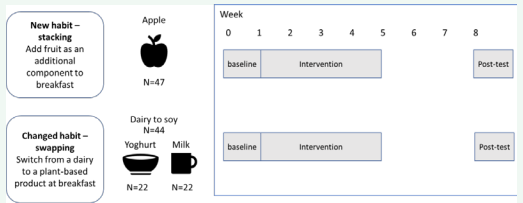

Current dietary patterns are often sub-optimal from a health and/or an ecological perspective. Changing dietary patterns is desirable, but difficult because of the persistence of food habits. Food habits are especially strong in breakfasting. This study explores two strategies for dietary behavioural change during breakfast: stacking, where a food component is added to an existing food habit, and swapping, where one food component is replaced by another one. Ninety-one participants (72 females, 19 males) adjusted their daily breakfast habits for four weeks by either adding a healthy food component (apple) to their existing breakfast or by swapping their less- sustainable dairy product for a more sustainable plant-based product (soy milk or soy yoghurt). Participant’s choice and liking of the breakfast was monitored daily with short questionnaires, whereas other information was collected weekly using more extensive questionnaires.

The results showed that both swapping and stacking strategies were equally effective during the 4-week study period (compliance>94%). During the study period liking for all three products increased initially but levelled off after 2 weeks for apples and soy yoghurt, whereas liking for soy milk continued to increase (p<0.05). All products were liked better by participants who scored relatively low on the HTAS reward and pleasure dimensions. The suitability of soy milk as breakfast component increased during the study period, whereas the suitability of the other products was either stable (apple) or decreased (soy yoghurt). The strength of the breakfast habit increased after the first week for apple and soy milk and decreased for soy yoghurt, signalling a growing integration of apple and soy milk in the existing breakfast habit. Breakfasts with apple triggered more positive emotions after 3 weeks than the two breakfasts with soy products.

Four weeks after the end of the study period, voluntary compliance with the products dropped to 26% for soy milk and to 15%-18% for apple and soy yoghurt. The results suggest that a long-lasting breakfast modification requires 1) a relatively small modification whereby one item is replaced by another item that serves the same function (e.g., replacing cow milk by soy milk), 2) a breakfast item that is increasingly liked over repeated exposure, and 3) does not require additional preparation. These findings provide a good basis for further research into consumer’s food habits, how they evolve and change, to ultimately facilitate development of new sustainable food products that better fit in existing and new habits.

Citation

De Wijk RA, Zandstra EH, Visser H, van Dijk BPM, Meijboom S, Vingerhoeds MH (2021) Breaking Breakfast Habits: Strategies for Healthier and More Sustainable Breakfast Habits. J Hum Nutr Food Sci 9(2): 1142.

INTRODUCTION

With the world’s growing population, the demand for a transition towards healthier and sustainable eating patterns is increasing [1,2]. The food industry plays a vital role in this transition with innovations that allow the production of healthy foods in a sustainable way. Unfortunately, about 50-70% of new food products fail in the market [3] despite prior rigorous sensory testing to assure appealing sensory properties. There are many different reasons for this high failure rate, but the main issue seems to be a lack of understanding of consumer behaviour [3-5]. It is clear that consumer behaviour is not only driven by sensory appeal but also by other factors. One important other factor is probably that food choice is largely driven by habits. Knowledge of how habits are and can be created, and under which circumstances they can be altered, is needed to help consumers in making their diet healthier and more sustainable.

Most of our daily food-related decisions are automated – or habitually triggered [6]. We get up out of bed, prepare our breakfast, which may be consumed while reading the news, and so on. Making radical changes in our food habits is notoriously difficult, as demonstrated, for example, by the low success rate of longer- term diet programs. Initially, our good intentions in combination with willpower are sufficient to initiate a change in food behaviour. However, good intentions and willpower are difficult – if not impossible – to maintain over periods of months and years, resulting in a cease of the newly acquired behaviour, also called habit [7,8]. One of the reasons for the difficulties in making radical changes is that existing habits do not only relate to the food choice behaviour itself but is part of a larger food- as well as non-food context. A definition of a habit is: “an automatic response to contextual cues, acquired through repetition of behaviour in the presence of these cues” [9]. A cue can be anything that could evoke a habit. Examples are sensory stimuli in the environment or internal states such as feeling hungry [10]. In the case of the breakfast example given earlier, this context includes waking-up when the alarm goes off, getting dressed, going to the kitchen, turning on of the coffee machine, and so on. Each step in this sequence of daily events automatically triggers the next step [7]. The automaticity of these events enables us to save time for other non-automated events, such as going through the planning of our coming workday. A radical behavioural change would disrupt all existing automated behaviours, which would take conscious effort, allowing less time for other non-automated activities.

This conscious effort should be maintained for a long time before it becomes habitual. Lally, Van Jaarsveld, Potts, and Wardle [11] investigated habit formation in everyday life for 12 weeks. Participants selected an eating, drinking or activity behaviour to carry out in the same context every day. Habit formation was measured through habit strength in the form of the selfreport habit index (SRHI) [12]. Lally et al. [11], found that habit development followed an asymptotic curve that took 18-254 days for participants to reach 95% of the asymptote. This seemed to differ for different kind of behaviours. For eating something healthy, it took about 65 days to reach this automaticity. For drinking something healthy, it took about 59 days.

A successful behavioural change may build on existing behaviours rather than starting completely new behaviours. A potentially fitting technique for implementing a new food habit while maintaining context consistency is stacking. The idea behind stacking is that a response itself could become a cue for another response. For example, Judah et al. [7], encouraged 50 British people to floss more often. Twenty-five of them were instructed to floss before brushing their teeth, the other 25 were instructed to floss after brushing their teeth. The latter one is stacking, because the habit of brushing the teeth would become a cue for flossing. After eight months, participants who were stacking flossed almost 3 times more per month in comparison to the participants who did not stack. Stacking works best if the new behaviour is compatible with an existent habit [13].

A related strategy for constructing a new habit on existent cues is swapping (or substitution). Here, the automatic habitual cue can be deployed for activating a swapped comparable habit. Swapping of food products is identified as one of six promising strategies for successful weight management by Gardner et al. [14]. However, as Gardner et al. pointed out, swapping will only be successful if the old and new (food) products are similarly attractive. Judah et al. [15], demonstrated that calory intake could be successfully reduced when high caloric sweetened beverages were swapped by well-liked low-calory alternatives or water. In the Netherlands, swapping is advocated by the Dutch Nutrition Centre (Voedingscentrum) to help consumers make small changes in their diet to make it more sustainable and/or healthy.

This study explores the effectiveness of swapping and stacking in changing breakfast habits into a more healthy or sustainable direction. Breakfast was selected because it is highly habitual with regard to the breakfast composition as well as to the context in which the breakfast is consumed (location, time, social context) [16]. As breakfast habits are often different in the weekend, this study was done on weekdays only. In the stacking condition, participants added an apple to their existing breakfast. In the swapping condition, participants replaced the dairy component of their breakfast (milk or yoghurt) by a plantbased product (soy milk or soy yoghurt). Compliance was tracked during the 4-week intervention period during which the apples and soy products were provided for free, as well as 1-month postintervention during which the products were no longer provided for free.

METHODS

In a between-subject design, participants were assigned to one of two experimental groups: (1) ‘soy group’ to change an existing breakfast habit, i.e. switch from a dairy product (yoghurt or milk) to a plant-based product (soy yoghurt or soy drink), and (2) ‘apple group’ to create a new breakfast habit, i.e. add fruit (apple) as an additional component to breakfast. During a period of 9 weeks, different aspects were measured, i.e. breakfast food choice, context stability, habit change and hedonic evaluations before, during and after the intervention.

Participants

Participants for this study were recruited from a previously conducted pilot study about breakfast habits with 294 participants. These participants had been recruited from the Wageningen University & Research database. Participants who indicated to be willing to participate in a follow-up study were sent a recruitment questionnaire to evaluate their current use of fruit and dairy products at breakfast. For inclusion in the current follow-up study, participants had to meet the following selection criteria: (1) Aged between 18 and 65 years, (2) Good command of the Dutch language, (3) No allergies or intolerances to the products offered in the study, (4) Having no special diet restrictions, and (5) Being able to collect the test products from a central location in Wageningen.

Participants were assigned to the soy group when they answered ‘almost always’ or ‘sometimes’ on the question of whether they usually consume dairy (milk, yoghurt or comparable products) during breakfast. Participants who did not consume any fruit during breakfast were selected for the apple group. The study started with 98 participants, of which 95 completed the study. Four participants had more than 5 missing days of using the test products and were therefore excluded from analysis. The population used for statistical analysis consisted of 91 participants, 47 in the apple group and 44 in the soy group with equal numbers in the soy milk and soy yoghurt subgroups (Table 1).

|

Table 1: Characteristics of participants classified by group (mean + SD). |

||||

|

Condition |

Stacking |

Swapping |

||

|

Product |

Apple (n = 47) |

Soy products (total) (n = 44) |

Soy yoghurt (n = 22) |

Soy milk (n = 22) |

|

Age (years) |

47.9 (12.6)a |

46.9 (13.0)a |

a 48.3 |

a 45.4 |

|

Male/Female (n) |

12 / 35 |

7 / 37 |

4 / 18 |

3 / 19 |

|

Intervention compliance (%) |

96.5a |

97.8a |

a 98.0 |

a 97.7 |

|

HTAS1 |

|

|

|

|

|

General health interest |

4.8 (1.4)a |

5.1 (1.4)b |

ab 5.1 |

5.1a |

|

Light product interest |

3.2 (1.5)a |

2.8 (1.8)b |

3.1b |

2.5b |

|

Natural product interest |

4.0 (1.8)a |

4.1 (1.8)a |

a 4.0 |

a 4.3 |

|

Craving for sweet foods |

3.8 (1.8)a |

4.4 (2.1)b |

b 4.5 |

b 4.3 |

|

Using food as a reward |

4.1 (1.8)a |

4.2 (1.9)a |

a 4.3 |

a 4.2 |

|

Pleasure |

5.1 (1.6)a |

5.3 (1.7)a |

a 5.3 |

a 5.3 |

|

VARSEEK2* |

a 3.6 (1.6) |

4.0 (1.6)b |

b 4.0 |

b 3.9 |

|

FNS3 |

2.9 (1.2)a |

2.6 (1.1)b |

b 2.6 |

b 2.6 |

|

Different letters in the same row denote significant differences according to independent sample t-tests. 1 Assesses the importance of perceived health and hedonic aspects of foods using six subscales. 38 items on a 7-point Likert scale with anchors “strongly disagree” (= 1) to “strongly agree” (=7) (Roininen et al., 1999) 2 Assesses degree of variety-seeking behaviour using 8 items, measured on a 5-point Likert scale with anchors “completely disagree” (= 1) to “completely agree” (= 5) (van Trijp, 1995). 3 Assesses food neophobia using 10 items, measured on a 7-point Likert scale with anchors “strongly disagree” (= 1) to “strongly agree” (= 7) (Pliner & Hobden, 1992). *n = 43 in the soy group, one participant did not complete the VARSEEK-scale. |

||||

All participants signed an informed consent and received a fee of 25 euros after completion of the study. Participants were told that the study was about breakfast habits, but they were kept ignorant of the actual aim of the study (i.e. to change an existing habit or create a new habit). This study has been approved by the Social Sciences Ethics Committee (SEC) of Wageningen University & Research.

Test products

The test products used were commercially available at the time of the study. For the soy group, an unsweetened soy drink and unsweetened soy yoghurt from the same brand (Albert Heijn private label) were chosen. The participants in this group received either the soy drink or the soy yoghurt for the duration of the study, depending on their current food choice at breakfast as established in the recruitment questionnaire. The apple group received apples of the Kanzi variety.

Participants collected their products at two pick-up moments (in week 1 and week 3 of the study), with instructions enclosed. The participants received products sufficient for two weeks, i.e. 10 weekdays per pick-up moment. A portion of 200 grams or ml per day was expected to be sufficient as a daily portion for the soy group. This meant that on each pick-up moment participants in the soy group received either two 1-liter containers of soy milk or four 500 gr packages of soy yoghurt. One participant in the soy group received a bigger portion of the soy yoghurts in the second week (10 packages), after indicating to habitually consume more yoghurt than the predetermined amount. The participants in the apple group received 10 apples per pick-up moment.

Two days before the pick-up moments, the individual portions were prepared for each participant. Both the apples and soy yoghurts were then stored in a cooler at approximately 4-5 degrees Celsius and taken out maximum 30 minutes before they were collected by the participants. The soy drinks were kept at room temperature. Both groups (apple and soy) were instructed to store the products in their refrigerators at home.

General procedure

The overall study lasted for a period of 9 weeks. An overview of the study design is shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1: Schematic overview of the study design.

This study consisted of three phases: (1) baseline, (2) intervention, and (3) post-test. The baseline phase consisted of 5 consecutive weekdays. The purpose of this phase was to evaluate the participants’ regular breakfast habits. After this week, the 4-week intervention phase started where participants had to use the test products for their weekday breakfast. Participants in the soy group were instructed to replace their original dairy product with the soy product during their breakfast. The apple group was instructed to add one apple to their daily breakfast. Both groups were explained that - apart from the replacing or adding of the breakfast products – they were allowed to use the products any way they liked during breakfast. Lastly, four weeks after the intervention phase had ended, the post-test took place. The goal of this phase was to evaluate whether the participants maintained their revised breakfast or whether they changed back to their original breakfast (Scheme 1).

Measurements

General. Questionnaires were used to assess different aspects of the breakfasts during each of the three phases of the study. The baseline and intervention phase used a daily short questionnaire (except on the first day of the intervention phase), and a more extensive questionnaire on Fridays. The post-test phase consisted of a single questionnaire. Participants were asked to fill out the questionnaires shortly after their breakfast. All measurements were completed at home by the participants using Eyequestion software (version 2018). Participants answered most questions on digital Visual Analogue Scales (VAS) ranging from 0 – 100. Before starting the study, participants completed the Health and Taste Attitude Scales (HTAS) [17]. These scales assess the importance of perceived health and hedonic aspects of foods. It consists of six different subscales, in which subjects answer 38 statements on a 7-point Likert scale with anchors “strongly disagree” (=1) and “strongly agree” (=7).

Baseline questionnaires. In the daily questionnaire, participants were asked what type of day it was for them (i.e. working day, study day, holiday, day off, vacation, other). Participants then recorded their food choice at breakfast and indicated how much they liked their breakfast that day (VAS with anchors “dislike extremely” to “like extremely”). On the last day of the baseline phase (at Friday), the questionnaire also included questions about context stability, habit strength, and desire to eat which were repeated on the Fridays during the intervention. Context stability was determined by the number of weekdays that the breakfast took place 1) at the same time, 2) at the same location, and 3) in the same company. A score of 4 or less was considered ‘less routinized’ and scores above were considered ‘routinized’.

Self-report habit index (SRHI) was used as a measure for habit strength on a 7-point Likert scale with the anchors ‘agree’ to ‘disagree’ [12]. The habit in question was followed by statements to which participant indicated in to what extent this applied for them. For example, item one: ‘The consumption of this breakfast is something I do automatically’. For the baseline week, all 12 items were used. The 12-item SRHI had a Cronbach’s alpha of .805. For the experiment week, item five items were excluded because these items dealt with the automaticity of the habit in terms of history with the habit or identification with the habits which does not apply for newly adjusted habits [11]. The Cronbach’s alpha for the 7-item SRHI was .768 for week 1, .858 for week 2, .828 for week 3 and .850 for week 4. To compare the habit strength of the different SRHI scores of both the 12-item questionnaire and the 7-item questionnaire, averages of the weekly scores will be used for the analysis. No items were recoded for this experiment.

Lastly, this end-of-week questionnaire included questions about attitudes and knowledge towards plant-based products.

Intervention questionnaires. During the intervention phase, participants were asked to fill out three different questionnaires, i.e. at first exposure-, daily- and weekly questionnaires. All three questionnaires in this phase started with a compliance question asking whether the participant had consumed the apple or soy product at breakfast that day (yes/no), and to indicate why if not.

First exposure questionnaire. The first exposure questionnaire was used on the first day that the participants were exposed to the test products. Participants were asked again to indicate what type of day it was for them (i.e. working day, study day, holiday, day off, vacation, other) and to record their breakfast and overall liking of their breakfast. After this, participants rated their remembered expected liking and desire- to-eat their breakfasts (same scales as in the baseline phase). They also rated appropriateness to eat the test product for breakfast (VAS scale with anchors “not appropriate at all” to “very appropriate”) and liking of the test product (VAS with anchors “dislike extremely” to “like extremely”). Lastly, they were asked if there was anything they particularly (dis)liked about their breakfast, and whether they preferred their regular breakfast or the “intervention” breakfast.

Daily questionnaire. The second questionnaire was used daily for the rest of the four weeks of the intervention phase – except for Fridays. It asked participants to indicate their day-type, to record their breakfast and overall liking of their breakfast.

Weekly questionnaire. The third type of questionnaire took place every Friday. This questionnaire repeated the same questions as the daily questionnaire, but also included questions about desire-to-eat, appropriateness and liking of the test product (same scales as before), boredom of overall breakfast (VAS scale with anchors “not at all” to “very much”) and whether they preferred their regular or “intervention” breakfast in the past 5 days. Furthermore, this questionnaire measured context stability, habit strength, emotions, other changes in breakfast habits, and obstruction of smell and taste perception during the last 5 days. In the apple group, participants indicated how they used the test product (e.g. in a smoothie or separate). The questionnaire for the soy group included a question about how similar the test product was to the regular dairy products they use (VAS scale with anchors “not similar at all” to “very similar”). Individual variety-seeking behaviour was evaluated with the VARSEEK-scale at the end of the second week of the study [18]. The VARSEEK is a tool used to measure the degree of variety seeking in consumers. It has 8 items with a 5-point Likert scale, labelled with “completely disagree” (=1) to “completely agree” (=5). Finally, food neophobia was measured at the end of week 4 using the Food Neophobia Scale (FNS) [19]. This scale includes 10 items, which are rated on a 7-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree’’ (= 1) to “strongly agree’’ (= 7).

Post-intervention questionnaire. The post-intervention questionnaire was filled out 4 weeks after the invention. In the post-intervention questionnaire, participants were asked to indicate whether they still had consumed the soy products or apples during breakfast in the weeks after the intervention phase had ended. They specified the frequency if doing so, reasons why or why not, and how long/whether they anticipated using the test products. Furthermore, they were asked whether they started using other plant-based products or fruit during breakfast, if the intervention caused other changes in their breakfast habits, and questions about sustainability and health attitudes. Finally, the participants rated liking and appropriateness of the test products once more.

Data analysis

Only the results on liking, desire-to-eat, appropriateness, boredom, and the attitude scales during the intervention phase, as well the post-test phase results will be described here. The results will be analysed for swapping (2 products) and stacking (1 product) conditions, as well for each of the three products. Mixed model analysis, performed in SPSS (IBM Corp. Version 25), used participants as random factor and intervention product and weekday as fixed factors.

HTAS, VARSEEK, FNS, and demographic measurements

The HTAS, VARSEEK, and FNS were analysed as described by Roininen et al. [17], 1 & Steenkamp [18] and Pliner & Hobden [19], respectively. For all three scales, this included recoding of the negatively worded statements and calculating the mean score per scale per group. Cronbach’s α was calculated for each (subscale) per group to check internal validity. Differences in age, intervention compliance, and the scales were compared between groups using independent sample t-tests, checking for equal variances in each comparison. Gender distribution in the two groups was checked using a chi-square test of independence.

Post-test and the relationship between habit change and hedonic measurements

To investigate whether habit change as measured in the post-test phase related to the hedonic measurements of the intervention phase, two groups were made: (1): continued use of the test products and (2) stopped using the test products. Demographic characteristics were evaluated and differences between the hedonic measurements performed during the posttest were compared using independent t- tests. Furthermore, the HTAS, VARSEEK, and FNS scores of the two groups were compared using independent sample t-tests. Gender and intervention group distributions were checked using chi-square tests of independence.

Next, mixed models were used to evaluate whether hedonic ratings measured during the intervention phase differed between participants that continued using the test products and participants that stopped using the test products.

RESULTS

Participants

Table 1 show the participant characteristics divided over condition (stacking and swapping) and products (apple, soy yoghurt and soy milk).

For HTAS, participants in the swapping condition scored significantly higher on ‘General health interest’ (p = 0.011) and ‘Craving for sweet foods’ (p < 0.001), and lower on ‘Light product interest’ (p = 0.004) compared to participants in the stacking condition.

For VASRSEEK and FNS, participants in the swapping condition scored significantly higher on variety-seeking behaviour (p < 0.001) and lower on food neophobia (p = 0.002) compared to participants in the stacking condition. The Cronbach’s α scores of all scales were at least 0.7, except for the ‘Pleasure’ subscale of HTAS with respectively 0.59 and 0.54 in the stacking and swapping condition. There was no significant difference between the conditions with respect to age and gender.

During the 4-week intervention

Compliance: Across test days and test weeks, compliancy rates remained high ranging between 94% and 100% irrespective of product (apple, soy yoghurt, soy milk), condition (swapping, stacking), weekday and week (Table 2).

|

Table 2: Percentage compliance per weekday and week during the intervention period for the stacking (apple) and swapping (soy yoghurt & milk) conditions. |

|||||||||

|

|

Week 1 |

Week 2 |

Week 3 |

Week 4 |

Mo |

Tue |

Wed |

Thu |

Fr |

|

Apple |

99 |

91 |

99 |

97 |

97 |

99 |

97 |

96 |

94 |

|

Soy yoghurt |

99 |

97 |

98 |

96 |

94 |

100 |

99 |

97 |

99 |

|

Soy milk |

98 |

96 |

98 |

99 |

98 |

100 |

99 |

95 |

98 |

Liking

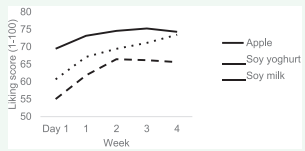

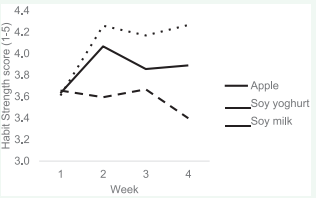

Liking scores for the breakfasts varied marginal significantly with product (F(2,88)=3.0, p=0.06) and weekday (F(4,1620)=2.3, p=0.06), and varied significantly with week (F(4,1620)=20.3, p<0.001). Interestingly, breakfast liking was dependent on the product and affected differently by week, as indicated by a significant product by week interaction (F(8,1620)=2.2, p=0.03) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Liking scores for breakfasts with apple, soy yoghurt and soy milk prior to the intervention (week 0) and during the intervention (week 1-4).

Liking scores for breakfast with apple and soy yoghurt levelled off after week 1 (apple) and week 2 (soy yoghurt), whereas liking for breakfast with soy milk continued to increase up to week 4 (Figure 1).

Liking scores were unrelated to HTAS, FNS or VARSEEK scores (all correlation coefficients <0.20, n.s.).

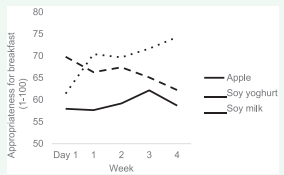

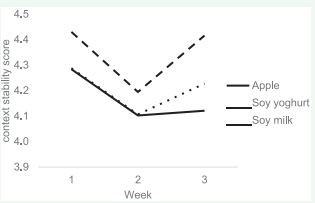

Appropriateness of products for breakfast

Overall, the appropriateness of the products for breakfasting did not vary with product. However, soy milk seemed to become more appropriate for breakfast over 4 weeks of exposure, whereas the appropriate of the other products either remained constant (apple) or decreased (soy yoghurt) as indicated by a marginally significant interaction of product and week (F(8,352)=1.8, p=0.08) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Appropriateness of apple, soy yoghurt and soy milk as breakfast items, in the period prior to the intervention (week 0) and during the 4-week intervention (week 1-4).

Appropriateness scores were unrelated to HTAS, FNS or VARSEEK scores (all correlation coefficients <0.20, n.s.).

Desire to switch back to original breakfast

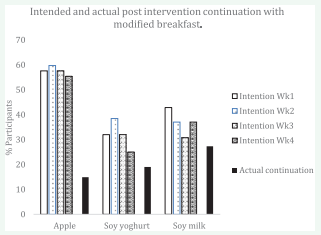

During the 4-week intervention, the majority of participants (approximately 60%) who added an apple to their breakfast indicated no desire to switch back to their original breakfast. In contrast, the majority of participants who swapped their breakfast item with soy yoghurt or soy milk did indicate a desire to switch back (60-70%) (Figure 3 week 1-4).

Figure 3: Percentage of participants that intend to continue with the new breakfast, based on the “No” responses to the question “If possible, would you want to switch back to your original breakfast?” during the 4-week intervention period. Post intervention percentages are the percentages of participants who voluntarily continued to use the product one month after the intervention.

Habit strength

The strength of the breakfast habit changed during the 4-week intervention period (F(3,186)=2.6, p=0.03). Inspection of the results showed an increase between week 1 and 2 followed by stabilization. This pattern did not vary significantly between products (interaction: F(4,186)=1.9, p=0.11). A separate analysis of the results for the swapping group showed different week effects for soy yoghurt and soy milk. Habit strength for breakfast with soy milk tended to increase over the weeks, whereas habit strength for breakfast with soy yoghurt tended to decrease (product x week interaction F(4,132)=3.0, p=0.05) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Habit strength for breakfasting during the 4-week intervention period.

Context stability

Context stability varied significantly per week (F(2,180)=4.9, p<0.001). Context stability did not vary with product (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Context stability for breakfasting during the intervention period

Post-intervention after 1 month

Eighteen percent of participants continued to use the products after the intervention period. The continuation rate was lowest for the participants who had added apple to their breakfast (15%), followed by the participants who had swapped their breakfast item by soy yoghurt (19%). The highest continuation rate was found for participants who had swapped their breakfast item by soy milk (27%) (Figure 3). The reasons given by participants for continuation or discontinuation varied between products (Table 3).

|

Table 3: Reasons for continued/discontinued use of the breakfast products one month post-intervention. |

|||

|

|

Apple |

Soy yoghurt |

Soy milk |

|

Reason for continued use (in %) |

|||

|

Taste |

86 |

25 |

50 |

|

Price |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Health |

71 |

100 |

50 |

|

Habit |

29 |

0 |

33 |

|

Ease of use |

29 |

0 |

0 |

|

Sustainability |

0 |

75 |

33 |

|

Reason for discontinued use (in %) |

|||

|

Taste dislike |

27 |

75 |

59 |

|

Price |

2 |

15 |

24 |

|

Not available |

20 |

5 |

29 |

|

Too much time |

20 |

0 |

0 |

|

Too little variation |

37 |

15 |

12 |

Liking of the taste and associated health benefits were the most prominent reasons for continued use of apple and soy milk. The most frequently mentioned reasons for continuation of soy yoghurt were health and sustainability benefits. Dislike of the taste was the most prominent reason for discontinued used of soy yoghurt and soy milk, whereas too little variation was the most prominent reason for discontinued use of apple. Continued or discontinued use by participants was not related to their stated moral obligation to live a sustainable and/ or healthy life (Table 3).

Discrimination analysis indicated that continuation was significantly related to relatively low HTAS ‘Food reward’ scores (p=0.001), and relatively high scores on liking (week 1: p=0.04, week 4: p=0.01), desire to eat (week 1: p=0.13, week 4: p=0.01), and appropriateness (week 1: p=0.004, week 4: p=0.001), especially at week 4 of the intervention. Finally, continuation of participants was associated with 1) low importance of affordability as driver for food choice, and 2) inability to modify recipes to make them healthier (efficacy).

DISCUSSION

This study explored the effectiveness of swapping and stacking in changing breakfast habits into a more healthy or sustainable direction. To this end, participants were provided with either a healthy (apple) or a sustainable (soy milk or soy yoghurt) breakfast component for an intervention period of 4 weeks. The apple was added – or stacked- to the existing breakfast, whereas the soy products replaced the dairy equivalent in the existing breakfast (swapping). During this intervention period participants showed a high compliance (>95%) in using their modified breakfasts. However, one month after the intervention ended, only 15%- 27% of the participants still consumed their modified breakfast, i.e., most participants returned to their original breakfasts soon after the intervention ended. Overall, the strategies of swapping and stacking to change breakfast habits were equally (un) successful in inducing longer- term changes in breakfast habits. However, the results also suggested that successful change in breakfast habits may depend more on the specific food product than on the type of intervention: whereas only 15% and 19% of the participants continued with using respectively apples and soy yoghurt in their breakfasts, a considerable higher percentage (27%) continued to use soy milk in their breakfasts. The results also showed that continuation of modified breakfast was partly related to the degree to liking of the breakfast, especially at the end of the intervention period when the modified breakfast had been consumed for four weeks. Similarly, participants who continued with their modified breakfasts not only liked their breakfasts better, but also felt a larger desire to eat the breakfast, and found the new breakfast item more appropriate for use in a breakfast, compared to participants who did not continue with their modified breakfast. Interestingly, participants who continued with their modified breakfast scored relatively low on using food as reward compared to other participants.

The relatively low continuation rates 1-month post intervention may be related to several factors. Firstly, breakfast is the most habitual meal of the day, making the breakfast habit most difficult to break, even when the changes are relatively small. Secondly, the intervention period used in this study is relatively short (20 breakfasts over a period of 4 weeks) to establish a new habit. This is considerably lower than for example the number of days reported for 95% habit formation for eating (65 days) or drinking (59 days) something healthy [8]. Thirdly, the habit modification of this study may seem relatively small from the perspective of the breakfast composition: only one breakfast item is either replaced or added. Behaviourally, the modification may be larger, especially in the case of apples that require additional time and effort to make them suitable for consumption. Finally, after the intervention, when the breakfast items were no longer provided for free, continuation of the modified breakfast required participants to incorporate the new breakfast item in their existing purchasing habits. This means that not only consumption and preparation habits needed to be modified but purchasing habits as well.

Given all these factors that may hinder successful habit formation, it is encouraging that even after this relatively short intervention period, up to one out of four participants (in the case of soy milk) continued using a more sustainable alternative in their habitual breakfast. The fact that soy milk was more successful in becoming a long-term part of the breakfast than soy yoghurt, shows that sustainability itself may not be an important factor in a successful breakfast habit change, as was also indicated by the fact that sustainability was rarely mentioned as reason for the continued use of soy milk. What is probably more important is that the new breakfast is liked and triggers a desire to eat. Taste like – or dislike- was mentioned most frequently as reason for continued – or discontinued- use of soy milk and soy yoghurt. More specifically, the results of this study suggest that the development of liking and for example the appropriateness of the item for breakfast during the intervention may be especially important. Inspection of Figures 1 and 2 shows that the breakfast item that participants continued to use most often (soy milk) is characterized by a growing liking and appropriateness over time rather than high absolute liking and appropriateness. These results are in line with the results of Judah et al. [15], who found that successful substitution of a high calory sweetened beverage by a low calory alternative – or water- depended on the liking of the alternative.

Actual post-intervention continuation rates showed little relation to anticipated continuation rates during intervention. Between 30% and 60% of the participants believed that they would continue to eat the modified breakfast after the intervention, while in fact only between 15% and 27% of the participants actually ate the new breakfasts 1 month later. The discrepancy was especially large for apples where approximately 60% believed that they would continue eating them as part of breakfast whereas only 15% did (Figure 3). The discrepancies were considerably smaller for the soy products, and especially for soy milk. As discussed above, incorporation of apples in an existing breakfast probably requires the largest change in habits because it is added to the existing breakfast, and it requires additional mental (how to integrate the apple in the existing breakfast) and physical (cleaning and preparation of the apple) activities. Possibly, participants underestimated the impact of apples on their existing habits and consequently overestimated the continued use of apples in the future. Interestingly, apple was the only breakfast product where taste was not the primary reason for not continuing after the end of the intervention. The primary reason was “lack of variation”. It is not clear why this reason was important for apple, but less important for the other two products. All in all, these results confirm results of numerous other studies that showed that good intentions are very difficult to realize, especially in the long run.

Limitations and strenghths of this study

Limitations of this study are the relatively low number of participants, especially in the sub-groups of soy milk and soy yoghurt, the relatively low number of male participants, and the relatively short intervention period. Consequently, many trends in the results failed to reach significance. Strong points of this study that it is one of the few studies that monitor actual changes in habits in real-life over prolonged periods of time.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that a longlasting breakfast modification requires 1) a relatively small modification whereby one item is replaced by another item that serves the same function (e.g., replacing cow milk by soy milk),

2) A breakfast item that is increasingly liked over repeated exposure, possibly as a result of increasing familiarity, and 3) a breakfast item that does not require additional preparation. These findings provide a good basis for further research into consumer’s food habits, how they evolve and change, to ultimately facilitate development of new sustainable food products that better fit in existing and new habits.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the Dutch Top Consortium for Knowledge and Innovation (TKI) Agri&Food together with Unilever Foods Innovation Centre Wageningen, Kikkoman Europe R&D Laboratory and Noldus Information Technology (TKI-AF-17005). We would like to thank Odette Paling for helping in the data collection and the recruitment of participants, and Garmt Dijksterhuis and Daisuke Kaneko for their contribution in setting up the design of the study.

REFERENCES

5. Lord JB. New product failure and success. In: Brody AL, Lord JB. (Edn). Developing new food products for a changing marketplace. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. 2000. 55-86.

10. Wendel S. Designing for behavior change: Applying psychology and behavioral economics. “O’Reilly Media, Inc”. 2013.

13. Labrecque JS, Wood W, Neal DT, Harrington N. Habit slips: When consumers unintentionally resist new products. J Acad Mark Sci. 2017; 45: 119-133.

16. Wood W. Gelukkig met gewoontes. Amsterdam: HarperCollins Holland. 2019.