Cultivating Natural Pigments A Cellular Approach

- 1. Division of Fermentation and Phytofarming Technology, CSIR-Institute of Himalayan Bioresource Technology Palampur, Himachal Pradesh- 176061, India

- 2. Academy of Scientific and Innovative Research, India

- 3. Department of Postharvest Sciences, Institute of Postharvest and Food Sciences, Agricultural Research Organisation, Israel

Abstract

Plant pigments are special compounds synthesized by them for their growth and survival in challenging environs that may be physiological, geographical and climatic. In addition, pigment molecules have a significant role in human life as natural colours and dyes, as well as in the management of health and wellbeing. Plant pigments such as carotenoids, anthocyanins, chlorophyll, betalains, naphthoquinones, flavonoids etc. are in great demand in industries like food, beverages, paper, textiles, cosmetics as well as in pharmaceuticals. This irresponsible harvesting of plant material from wild not only depletes natural resources but also fails to meet the growing industrial demand. Thus, it is important to establish more sustainable and ecologically friendly processes for the production of raw materials that can be used to extract pigments. In this context, scientific communities deployed plant cell and tissue culture technologies to produce certain plant-based constituents successfully on industrial scale. A number of reports are available that demonstrated the use of in vitro plant cultures as a sustainable method to get commercially valuable natural products (ginseng, berberin, rosmarinic acid, podophyllotoxins etc.) including pigments like anthocyanins and betacyanins. In this article, publications reported deployment of plant cell and tissues-based system for natural pigments are discussed. In addition, the information on strategies such as elicitation, precursor feeding, permeabilization, immobilization and two-phase cultivation system deployed to maximize the productivity, especially under in vitro condition. Emphasis is also done on extraction of plant pigments from conventional as well as green advanced techniques. It will not only eliminate the dependency on wild plants but will also help in meeting industrial demand and conservation of continuously depleting natural resources.

Keywords

• Cell & tissue culture; Naphthoquinones; Anthocyanin; Bioreactor; Extraction; colour.

Citation

Devi J, Dhrek MS, Bhushan S (2025) Cultivating Natural Pigments: A Cellular Approach. J Hum Nutr Food Sci 13(2): 1198.

INTRODUCTION

Natural is the consumer-preferred catchphrase, and it is currently impacting not only dietary decisions, but also stirring every aspect of life, including health, personal care and lifestyle-related products. Specifically, the natural ingredients are compounds that have an effect on biological systems and can be derived from plants, microorganisms, and other biological sources. Among all these sources, plants based natural ingredients often have a wider acceptance among consumers owing to their pre-historic use, safety, potential health benefits and eco friendly characteristics. Often plants are known to contain a variety of natural ingredients in the form of primary and secondary metabolites that has application in food, fibres, pigments, fatty oils, sugar, starches, pulp and paper, rubber, gum, resins etc. In addition, some of these plant molecules known as pigments absorb different wavelengths of visible light, giving plants vibrant colours e.g. anthocyanins absorb blue and green light, reflecting red to purple hues. Primarily, these compounds are essential to support photosynthesis, protect against environmental stress, and help in reproductive phase [1,2]. The attractive and bioactive nature of pigment compounds also served human civilization for centuries and cater their needs in foods, textile and cosmetics. Besides application as colourants, these molecules are an integral part of traditional system of medicine and used as nutraceuticals, additives and pharmaceuticals [3]. Specifically, the carotenoids contribute to eye health and immune function, while anthocyanins have potent antioxidant and anti inflammatory properties [4]. In present. The natural pigments are being widely used in food and personal care products, replacing synthetic dyes, with safer and biologically active alternatives. Unlike synthetic pigments, the plant-based ingredients are non-toxic and biodegradable with no associated risk to human health and environment. The rise in demand for natural pigments surged due to growing consumer awareness for clean-label and sustainable alternatives, and more importantly to the evidence based scientific validation [5]. Traditionally, the natural pigments are extracted from the material largely collected indiscriminately, which are resource-intensive and non-sustainable methods. In order to overcome these challenges, the biotechnological advancements have introduced more sustainable approaches such as plant cell & tissue cultures and synthetic biology platforms that enables the heterologous production of high value pigments [6]. These strategies not only paving the way for sustainable and eco-friendly production of natural pigments, but also enabling process scalability and reducing dependency on seasonal and geographical hurdles. Therefore, efforts are made in this article to assess the ecologically sustainable and environment friendly solutions available based on plant cell and tissue culture to produce pigments that can meet the growing public and industrial demand as well as able to protect natural resources.

Key Plant Pigments

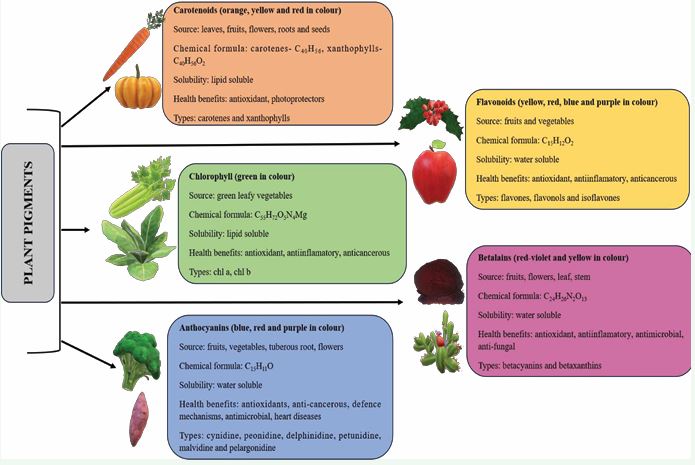

Plant pigments have several categories, each with distinct colour and activities [Figure 1].

Figure 1 Major classes of plant pigments.

The common plant pigments includes chlorophylls, carotenoids, anthocyanins, flavonoids and betalains [7].

Market Potential of Natural Pigments

Plant pigments are used in every domain of human life. The worldwide market for dyes and pigments was estimated to be worth USD 38.2 billion in 2022, and between 2023 and 2030, it is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.3% [8]. By 2026, it is anticipated that India will import nearly 4 million kilograms of pigment and export 39 million kilograms of pigment. The estimated global market value for food colour is USD 4.6 Billion in 2023 and expected to reach USD 6.0 Billion @ 5.4% Cumulative Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) by 2028 [9]. Alone, natural food colour market is expected to reach USD 92.96 Million by 2027 with 3.90% CAGR [10]. Besides food, these pigments are also in huge demand by cosmetic industries. With a CAGR of almost 5.8% from 2022 to 2030, the market for cosmetic pigments was anticipated to be worth USD 680.1 million in 2021. By 2030, the market will have risen to around USD 1,125.5 million. [11].The factors for this acceleration are increased health awareness, changing life style and demand for environment-friendly constituents across the world. Because of qualities like good soaking, darker color, and thinness, inorganic pigments achieved a larger market share than organic pigments. But from 2023 to 2030, the organic pigments market is anticipated to expand at the most-fastest rate, with a 5.7% CAGR in sales. Whereas, the natural food colors market is predicted to reach USD 1.7 billion by 2034 with a CAGR of 8.32% from USD 1.57 billion estimated in 2024 [12]. Globally, Asia pacific is forecasted to be the largest market of herbal pigments with upmost accelerated growth expected in India. Market reports are also available on individual class of natural pigments used in various industries. USD 2.9 billion by 2029 from USD 2.0 billion in 2024 for carotenoids [13], and USD 314.9 million by 2035 from USD 114 million in 2025 with 10.7% CAGR for lycopene [14].

The natural plant pigments are gaining prominence as sustainable and safe alternatives to synthetic dyes. The growth in this sector mainly driven by rising consumer demand for clean products, regulatory framework and environmental concerns. and natural ingredient-based food, especially plant-based products. Swami and co authours provided a comprehensive report on plant pigments, and discussed the challenges in stability, scalability and sustainability that hinder their broader industrial application [2]. Thus, there is an immediate need for technological innovation and policy support to unlock the full potential of natural pigment in global market. In this regard, the success of Mitsui Petrochemical Industries Ltd. during 1980s in producing red pigment i.e. shikonin by using cell suspension culture of Lithospermum erythrorhizon was the first milestone [15]. Japan Tobacco Inc. produced ubiquinone-10 from Nicotiana tabacum strains using cell cloning method [16]. Besides these, there are numerous examples available that clearly demonstrated the utilization of plant cell, tissue and organ culture technology for production of phytochemicals such as ginsenosides (Panax ginseng), caffeic acid derivatives (Echinacea purpurea), total phenolics (Polygonum multiflorum), hypericin (Hypericum perforatum) and anthocyanins in large scale bioreactor system [17,18].

PLANT CELL AND TISSUE CULTURE TECHNOLOGY

Plant tissue culture technology is most reliable and well -established system and widely used for micro propagation of plants at large scale. Apart from plant propagation, this technique has been efficiently used for production of commercially important secondary metabolites. In recent years, there are number of reports published that support this notion, especially for successful growing plant cell and organ cultures in industrial scale bioreactors [19]. Plant tissue culture technology holds immense potential for monitored year-round synthesis and extraction of useful phytochemicals independent of geographical and environmental boundaries. Similar to fermentation technology, factors such as optimum supply of nutrients, medium pH, adequate temperature, humidity and light affect the in vitro grown cell and tissue cultures. It is pertinent to mention here that the plant cells are more shear sensitive owing to larger size than animal and microbial. Hence, optimum agitation, adequate media volume and precise gaseous composition of micro environment are crucial for maximum productivity. Even the selection of explant source i.e. mother plants as well as its specific parts (leaves, stems, roots and meristems) is equally important to get high growth and metabolite accumulation in cell or organ culture lines. This system is emerging as a boon for such plants, in which conventional propagation is difficult, and plant grow slowly or take much time till its parts such as leaves, shoot or roots become mature enough for intended purpose [20]. The key advantages of plant tissue culture technologies are tremendous as compared to field cultivation as highlighted below [21]:

- Mass propagation of difficult to cultivate, slow growing and long growth period plants

- Independent of sessional variations and geographical boundaries

- Stable, reliable and predictable metabolic profile

- Phytochemicals extraction is efficient, fast and cost effective without harming the natural resources

- Free from contamination and diseases

- Less land and labour requirement, and

- Year-round production

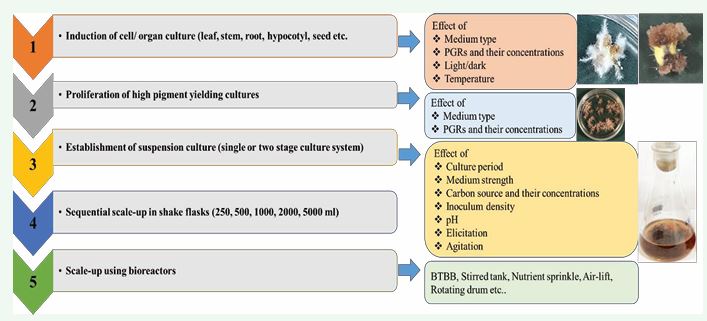

Biotechnology provides an opportunity for the maintenance of plant cells or tissue by growing them in vitro as well as in bioreactors for scaled-up production of specific metabolites. The production of such phytoconstituents using in vitro plant cultures has gained more attention over past couple of years. A general flow-sheet for the production of such highly valuable compounds including pigments through in vitro plant cell and organ culture technology is presented [Figure 2].

Figure 2 Flow chart depicting pigment production using plant cell, tissue and organ culture technology

The various aspects important for plant tissue culture technology are described in brief for the convenience of readers here, under following subheads:

CULTURE ROOM AND ITS ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITION

Culture room is a place where different types of cultures can be maintained under high level of asepsis. It must have media storage area, inoculation chamber or Laminar-Flow, working stools/chairs and incubation racks. These rooms are quite similar to operation theatre having double doors entry, tightly sealed windows and ventilators with restricted access to avoid contamination. In general, illumination (photosynthetic photon flux density of 70 µmol m-2 s-1 with a 16 hrs photoperiod) for positively phototrophic cultures, temperature (25±2ºC) and humidity (40-60%) are tightly regulated, probably with auto control system.

Media and plant growth regulators

A number of plant tissue culture media are available and in order to have optimum growth, appropriate medium will be selected depending upon type of plant and cultures to be developed. However, the basic components of these media are carbon source, macro & microelements, vitamins, amino acids and phytohormones. Commonly used media are MS [22], B5 [23], WH [24], LS [25], Nitsch’s [26], SH [27], and Woody Plant Medium [28]. Sucrose at a concentration of 2-5% is commonly used as carbon and energy source. Vitamins employed in plant tissue culture media are thiamine, pyridoxine, nicotinic acid, meso inositol and glycine. Among plant growth regulators, auxins, cytokinins, gibberellins, abscisic acid and polyamines constitute the major groups broadly used in plant tissue culture growth media at different proportions. In addition, the medium pH plays crucial role in determining in vitro development features of plant cells or tissues. Generally, the optimum pH advocated for use in plant cultures is in the range of 5.7-5.8.

Establishment of in vitro cultures

Totipotency- a term given for the capability of single plant cell to produce whole plant. Plant tissue culture technique is based on this property for large scale in vitro propagation and to produce phytochemicals directly (from plant parts) or indirectly (through callus culture). There are various types of in vitro systems such as callus, seed, anther, embryo, ovary, protoplast or organ (root, shoot, leaves etc.) cultures used as per requirement and cultivation choice. Depending upon the regeneration capability of plant species, their different parts i.e. aerial or underground, vegetative or reproductive are used as ‘explants’ to initiate in vitro cultures. For the induction purpose, explants need to be thoroughly washed in running tap water and then with deionized water containing 1–2 drops of surfactant like Tween–20. These are then surface sterilized with antifungal and antimicrobial agents e.g. bavistin and streptomycin for variable times (8-10 min), followed by exposure of 70% ethanol only for few seconds. If required, the explants were also treated with very low concertation of mercuric chloride (0.1-0.5%) 1-2 min and then washed thoroughly (3-4 times) with sterile distilled water. The sterilized explants are inoculated in flasks/jars or petri plates containing appropriate autoclaved (at 15 psi and 121ºC for 20 min) media under aseptic condition. Based on culture conditions, two types of mediua are used in plant cell and tissue culture i.e. 1. Semisolid medium (agar-agar (0.8-1.0%) or gelrite powder as gelling agent) and 2. liquid medium (without use of gelling agent). Establishment of in vitro cultures involves development of adventitious organs or primordia either directly on explant or through callus, an undifferentiated mass of cells. In general, the production of pigment molecules is done by forming either plant cell or organ suspension cultures, as is easy for subsequent scale up in bioreactors. Here, we have described about two types of cultures i.e. callus and organ culture generally deployed for phytochemical production at industrial scale.

Callus and cell suspension culture

Callus consists of actively dividing cells and may develop into plantlets by redifferentiation. However, there are chances of genetic variations occurrence owing to mitotic level changes during cultivation. With subsequent culturing, cell suspension cultures are raised through inoculation of callus cultures in liquid medium kept on incubated shakers. The rotation speed (50-150 rpm) and inoculum density are two important variables for establishing suspension culture successfully. Constant shaking of cultures is required to facilitate dissociation of cell clumps to single cells or smaller clumps comprised of few cells and also for aeration. On an appropriate medium cell suspension cultures grow much faster and needs to be sub cultured at regular intervals of 10-12 days. If sub culturing is delayed, the growth of the cells started declining. Besides organogenetic response, such cultures are used for scaling up studies in bioreactors for the mass production of phytochemicals as well. Such type of cultures, where suspended cells proliferate or divide when continuously agitated in a liquid medium known as suspension cultures. The homogeneity, high proliferation and good reproducibility of suspended cells, make them suitable to study complex physio-chemical processes at the cellular and molecular levels [29]. There are various pigments which are produced by the plants in response to various types of stresses, these include numerous polyphenolic compounds (naphthoquinones, anthraquinones, anthocyanins and flavonoids) and now-a days many reports are available on the production of these bioactive compounds by in vitro cultured plant tissues.

Organ culture

Organ culture can be categorized into two major classes i.e., vegetative organ culture like root, shoot, leaf culture and reproductive organ culture like ovary, embryo, ovule, anther and pollen culture. The regeneration ability of these explants depends upon the plant species and also the type of medium constituents used for culture establishment. In recent years a lot of emphasize given on adventitious and/or hairy root cultures [18, 30]. In general, roots of numerous plant species, especially medicinal and aromatic, are the site for the accumulation of key bioactives such as alkaloids, sesquiterpenes, monoterpenes and naphthoquinones. Hairy roots are induced by infecting the explant with Agrobacterium rhizogenes, which are then separated and cultivated indefinitely under aseptic environment. The phytochemical synthesis is stable in these roots over succeeding generations owing to their genetic stability. In contrast, adventitious roots are induced from non-radicle plant parts by in vitro methods, however, without any genetic transformation. These roots also showed fast growth and vigorous secondary metabolism [31]. Adventitious roots are natural, grown in phytohormones containing medium and show tremendous capability for the accumulation of secondary metabolites [32,18]. These root cultures advocated to be a potential ingredient with comparable or higher metabolites yield within shorter time as compared to their field grown counterpart. However, adventitious roots being induced without any genetic alteration seems to have an edge over hairy root cultures.

IN VITRO PIGMENT PRODUCTION

Numerous pigments such as naphthoquinones, anthraquinones, anthocyanin and flavonoids are produced by the plants in response to various types of stresses naturally. The demand for such natural colorants is rising continuously. However, wild resources or field cultivation is not sufficient to meet this growing demand and therefore, biotechnological strategies like plant tissue and cell culture can work as wonder to fulfil this demand. In vitro plant cell, tissue and organ culture technique involves the following steps for the production of desired metabolites [Figure 3].

Figure 3 Flow chart for pigment production under in vitro conditions from A. euchroma adventitious roots

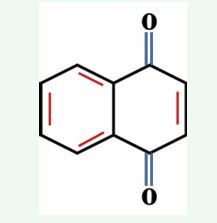

Naphthoquinones

Naphthoquinones, a red- purple pigments reported from plants of Boraginaceae family, includes different species of Arnebia, Lithospermum, Alkanna, Echium and Onosma. Commercially, shikonin and its derivatives are the most important polyphenol class of naphthoquinone pigments having wide range of pharmaceutical properties, besides their main application as natural dyes for colouring food, fibre, hairs as well as other cosmetics [33]. These compounds are extracted from the plant roots, as accumulated in the outer surface. Chemical structure of naphthoquinones is represented in Figure 4.

Figure 4 General structure of naphthoquinones.

In 1984, for the first time, shikonin pigments were upscaled from cell suspension cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon by Mitsui Petrochemical Industries Ltd., Japan [16]. Callus was induced from seedlings on LS basal (Linsmaier and Skoog 1965) agar medium augmented with kinetin and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D). However, with subsequent sub culturing and cultivation of callus under dark at 25°C in same medium containing indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) led to production of red pigment i.e. shikonin derivatives [34]. Repeated selection enabled screening of ‘M18’ high pigment yielding cell line (20-fold increase over the original) from callus cultures of L. erythrorhizon [34]. In vitro condition as well as physical factors like carbon source, light, temperature and extraction methods such as low-energy ultrasound, and sonication were manipulated to maximize the pigment yield [36]. Similarly, efforts were made to produce naphthoquinone pigments using Arnebia euchroma cell and tissue culture. Callus was induced on MS medium supplemented with 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) and indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) from different explants (leaf, root) of A. euchroma [37]. Induced callus was then further multiplied in the same medium for the maintenance of mother cultures/ stock. After that cell lines showing potential for the production of pigment were screened and used for the initiation of suspension culture. Generally, A. euchroma engaged in a two-stage culture system in which growth and production was achieved in two different media i.e. growth and production media respectively. Pigment production in these cultures was affected by several factors like inoculum type (direct: liquid to liquid or indirect: solid to liquid), phosphate sources, medium pH, light, temperature, sucrose concentration and extraction methods. Researchers found that direct inoculum (solid to liquid) (19.53% yield), potassium phosphate source (KH2 PO4 and K2 HPO4 ), 25°C temperature, 7.25-9.50 pH and 6% sucrose in medium favoured production of pigment, however, light conditions completely inhibits the naphthoquinone pigment production in A. euchroma [38]. Similarly, production of napthoquinone were also reported from shoot induced adventitious roots of A. euchroma [39]. Production of naphthoquinones also reported to be influenced by type of explant, donor plant and growth regulators. It is reported that in vitro cultures induced from the high pigment-yielding mother plants had better efficiency for secondary compound production [40]. Naphthoquinones were also found to be produced by in vitro cultured Dionaea muscipula and Drosera species grown on a hormone-free medium [41]. In another study on Drosera spatulata, Chang et al., reported that in commercial crude drugs the content of plumbagin was the highest, then tissue culture hardened plants and in in vitro shoots [42].

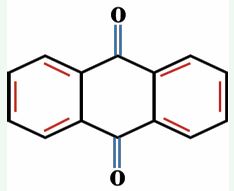

Anthraquinones

Anthraquinones are important and vital plant pigments ranging from greenish yellow to bluish green in colour. These pigments accumulate in roots, rhizomes, flowers and fruits of the plants. Chemically anthraquinones has three cyclic rings [Figure 5].

Figure 5 General structure of anthraquinones.

Members of family Rubiaceae and Polygonaceae are reported for the presence of these pigments which includes different species of Morinda, Polygonum and Gynochthodes. Cell suspension culture of Morinda citrifolia established in B5-medium containing 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) found to produce anthraquinone pigments in exponential and the stationary phase of the cultures [43]. In another study on adventitious roots of M. citrifolia, maximum contents of anthraquinone was reported in medium containing thidiazuron (TDZ) and IBA [44]. In case of M. elliptica, sucrose concentration, culture age, incubation temperature and illumination largely affect anthraquinone formation in cell culture under submerged condition [45]. However, in another study on M. elliptica cell suspension culture, two novel anthraquinones i.e. anthragallol-1,2- dimethyl ether and purpurin-1-methyl ether were reported [46]. In Polygonum multiflorum cell suspension culture established in MS medium augmented with 2,4-D, TDZ and glutamine found to produce emodin and physcion after 28 days of culture [47]. In M. royoc root cultures, maximum anthraquinone accumulation was favoured in IAA supplemented MS medium [48]. In Rubia akane, hairy roots cultured in full strength of SH medium with NAA yielded maximum alizarin and purpurin content [49]. However, in P. multiflorum, hairy roots accumulated 2.55-fold higher content of rhein than that of mother plant [50].

Anthocyanin

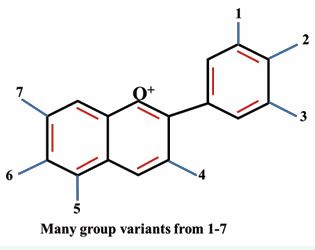

Anthocyanin pigments are found in many plant species, expressly in flower petals and fruits. These pigments serve as additives in food and beverage as well as have anti-cancerous and hepato-protective properties [51,52]. Anthocyanins have C6-C3-C6 structure with two benzene rings joined by third one [Figure 6],

Figure 6 General structure of anthocyanins.

and their production have already been reported in numerous plants by tissue culture methods. Particularly, detailed studies on anthocyanin production was done on Haplopappus gracilis [53], Populus hybrid [54] and Daucus carota [55]. In Vitis, higher pigment producing cell lines with stable metabolic profile was obtained by using anther explant on MS medium having 2,4-D. Additionally, ammonium and nitrate ratio, sucrose, inorganic nitrogen and phosphate concentration, and light intensity largely affect anthocyanin production in cells cultured in liquid medium [56]. In D.carota, suspension culture, lower KH2 PO4 concentration and NH4 NO3 to KNO3 ratio cause 1.63-fold and 2.85-fold rise in anthocyanin content respectively [57]. MS medium with 2,4-D, NAA and 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) was used for the initiation and routinely maintenance of callus culture in Angelica archangelica, however, LS medium was responsible for the maximum accumulation (114%) of anthocyanin [58]. Anthocyanin production from Bridelia retusa callus cultures was reported to be influenced by pH, light, temperature, irradiation and carbon source used in the medium [59]. The adventitious roots of Raphanus sativus were formed by culturing in vitro root segments in 1/2 strength MS liquid medium fortified with IBA. The anthocyanin production in these cultures under light conditions was slightly higher (0.15% dry weight) than that of the field-grown roots (0.11% dry weight) [60].

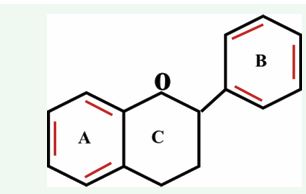

Flavonoids

Flavonoids are polyphenolic compounds thoroughly distributed in foodstuffs of plant origin. Their systematic intake in diet is linked with reduced risk of certain illnesses including chronic, cancer, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disorder. Chemically, flavonoids contains two benzene rings joined by an oxygen containing heterocyclic ring. In plant tissue culture, production of flavonoids is associated with optimization of various physiochemical parameters including, medium and PGR’s type, pH, temperature, sucrose concentration, inoculum density etc. In Glycyrrhiza inflata cell suspension culture, improved production of flavonoids was related with optimization of inoculum densities, sucrose and nitrogen concentrations. Additionally, authors have reported that, productivity of flavonoid was higher in cells cultivated for 3 years as compared to the mother plant (3-year-old) [61]. Chemical investigation of cell extract via HPLC and TLC methods, in Astragalus missouriensis led the isolation of different flavonoids. However, authors have studied the effect of auxin, cytokinin, and sucrose, light/dark conditions for the improved production of flavonoids [62]. In Ginkgo biloba, MS medium supplemented with NAA and BAP was liable for the establishment of callus culture as well as for the production of flavonoids and terpene lactones [63]. In Isatis tinctoria, LC-MS/MS examination inveterate the occurrence of eight flavonoids (rutin, neohesperidin, buddleoside, liquiritigenin, quercetin, isorhamnetin, kaempferol and isoliquiritigenin) in hairy root cultures. However, optimization of culture environment led to higher total flavonoid production than mother plant roots of 2-year-old [64]. In Hypericum perforatum adventitious root cultures, ratio of NH4 Cl and KNO3 (as ammonium and nitrate) largely influenced the accumulation of flavonoids after 5 weeks of cultivation in dark [65] (Figure 7).

Figure 7 General structure of flavonoids.

Additionally, cell aggregates size and pH also influenced the accumulation of biomass and flavonoids in Ficus deltoidea cell suspension cultures. Authors have reported that accumulation of flavonoids is in a direct relation with cell aggregates size. However, acidic pH (5.75) results in the highest flavonoid content in cell suspension culture of F. deltoidea [66]. In F. esculentum, hairy roots were induced by transforming leaf and stem explants with A4 strain of A. rhizogenes for the production of flavonoids [67]. In recent years, a number of reports are published that advocates the use of in vitro cultured plant tissues for production of these compounds [Table 1].

Table 1: Plant pigment production using in vitro culture system

|

Pigment type |

Plant species |

Explant used |

Culture type |

Medium used |

References |

|

Naphthoquinones |

Arnebia euchroma |

leaf, root |

Cell suspension |

MS+10.0 μM BAP +5.0 μM IBA |

37 |

|

Lithospermum erythrorhizon |

seedlings |

Cell suspension |

LS +10-6 M IAA+ 10-5 M kinetin |

34, 35 |

|

|

Impatiens balsamina |

leaf |

root cultures |

Gamborg’s B5 |

40 |

|

|

Arnebia euchroma |

cotyledons |

Adventitious roots |

- |

39 |

|

|

Anthraquinones |

Rudgea jasminoides |

ex vitro leaves |

cell suspension culture |

½ MS + 0.55 µM myo-inositol, 0.31 µM thiamine-HCl, 8 nM nicotinic acid+5 nM pyridoxine-HCl, 0.82 µM cysteine, 5% coconut water and 87.6 µM sucrose |

68 |

|

Polygonum multiflorum |

in vitro root explant |

cell suspension culture |

MS+1.0 mg/L 2,4-D+0.5 mg/L TDZ+100 µM L-glutamine |

47 |

|

|

Gynochthodes umbellate |

adventitious roots |

cell suspension culture |

MS +2.0 mg/L IAA |

69 |

|

|

Anthraquinones |

Morinda royoc |

in vitro roots |

Root culture |

MS+5.7 µM of IAA |

48 |

|

Morinda citrifolia |

in vitro leaf explant |

Adventitious roots |

MS+0.5 mg/L TDZ+ 5.0 mg/L IBA |

44 |

|

|

Daucus carota |

leaf explants |

cell suspension culture |

MS+ 8.88 µM BAP + 5.37 µM NAA + 20.0 mM: 37.6 mM NH4NO3 to KNO3 ratio |

57 |

|

|

Bridelia retusa |

stem tips and leaf explants |

cell suspension culture |

MS+2.0 mg/L 2,4-D and 2.5 mg/L BAP |

59 |

|

|

Daucus carota |

taproot and hypocotyl |

hairy root culture |

½MS |

70 |

|

|

Raphanus sativus |

root segments |

adventitious roots |

½MS + 0.5 mg/l IBA |

60 |

|

|

Flavonoids |

Astragalus missouriensis |

- |

cell suspension culture |

MS+ 1 mg/L NAA+ 2 mg/l kinetin+6% sucrose |

62 |

|

Centella asiatica |

leaf explants |

callus culture |

MS+2.0 mg/L 2,4-D |

71 |

|

|

Ginkgo biloba |

embryo |

callus culture |

MS+2.0 mg/L NAA + 1.0 mg/L BAP |

63 |

|

|

Ficus deltoidea |

leaf explant |

cell suspension culture |

MS+ Gamborg B5 vitamins +2.0 mg/L picloram + 1 mg/L kinetin |

66 |

|

|

Hypericum perforatum |

leaf |

adventitious root culture |

½ MS medium + B5 vitamins+ 1.0 mg/L IBA+ 0.1 mg/L kinetin, 3% sucrose+ 5:25 mM NH4+/NO3− |

65 |

|

|

Genista tinctoria |

in vitro shoots |

hairy root culture |

SH |

72 |

IMPROVEMENT OF PIGMENT PRODUCTION

Plant tissue culture technology holds great potential for the production of useful pigments by utilizing cell and organ cultures. However, production of these pigments is not always satisfactory utilizing these cultures for commercial exploitation with a few exceptions [73]. Therefore, efforts have been engrossed to mend the production capabilities of these cultures by employing various methods including elicitation, precursor feeding, permeabilization and immobilization, and two-phase culture system.

Elicitation

An elicitor is a substance or compound which when imposed to the cultures in relatively small concentration, either initiate or enhance the synthesis of bioactive phytoconstituents [74]. These can be defined as biotic elicitors from living origin like yeast extract and enzymes, and abiotic elicitors from non-living origin like jasmonic acid (JA), methyl jasmonate (MJ) [18]. Usually, elicitors are frequently used to boost the production of secondary products in in vitro cultures. A number of biotic and abiotic elicitors are reported under in vitro conditions to boosts the metabolite production including cellulose, pectin and chitin as biotic elicitors and MJ, JA, salicylic acid (SA), copper sulphate, sulphate, silver nitrate, sorbitol as abiotic elicitors [74]. In L. erythrorhizon endogenous polysaccharides enhance shikonin derivative production in cell suspension culture [76], however, enhanced production of the same from A. euchroma was reported by use of fungal elicitor Rhizopus oryzae and rare earth elements [77,78]. In cell suspension cultures of Oldenlandia umbellata, Krishnan and Siril reported the use of pectin for the enhancement of anthraquinone [79]. In Vitis vinifera cell suspension cultures, chitosan, pectin and alginate led to 2.5, 2.5, and 2.6-fold increase in production of anthroquinone respectively [80]. In M. citrifolia adventitious root cultures, addition of chitosan on day 28th of cultures for 2 days improves production of anthraquinone [81]. MJ cause 2.7- fold increase in flavonoid production in H. perforatum cell suspension culture [82]. Similary, induction of Ipomoea batatas cell suspension cultures with MJ leads to significant accumulation of anthocyanin pigments [83].

Precursor feeding

Precursor feeding is another successful strategy for increasing the synthesis of secondary metabolites under in vitro conditions. On the basis of information on the biosynthetic pathways, exogenous applications of organic composites to culture medium boost the synthesis of desired compounds. The notion is that any compound within the way of biosynthetic pathway, stances a chance to enhance the final product formation [84]. In V. vinifera, feeding of phenylalanine at the starting of the exponential phase cause 6.1 -fold increases in anthocyanin production [85]. However, feeding of the same in hairy root cultures of Psoralea corylifolia resulted in 1.3 -fold increased accumulation of daidzein and genistein [86]. Similarly, phenylalanine incorporation causes 81% increase in anthocyanin formation in strawberry cell suspension cultures [87].

Permeabilization

Permeabilization of cells is a way of cell cracking. Most of the times, plant secondary products accumulate inside the vacuoles and secreted into the medium either naturally or through artificial mode. Naturally, there secretion involves either passive or active diffusion [88]. However, efforts were done to secrete such intracellular compounds into the medium. Cell permeabilization creates pore in the membrane system, facilitating the easy entry and exit of the molecules across the cells [89]. Permeabilizing agents are not inhibitory to the growth of cells and have the capability to expand the diameter of the pores [90]. By using surfactant pluronic F-68 as permeabilizing agent, Basetti et al., reported the release of anthraquinones from cells of M. citrifolia in to the medium [91]. However,dimethylsulfoxide dissolved chitosan cause increased content of amaranthin in Chenopodium rubrum cell cultures [91].

Immobilization

The process of immobilization allows plant cells to remain motionless within or on top of a matrix or supporting substance. The process is carried out using various methods like entrapment, adsorption and covalent coupling of the cells with supporting material or matrix. The supporting material causes the entrapment of cells in some kind of gels like agar, agarose or other chemicals like calcium alginate, glass or polyurethane foam causing the polymerization of cells around them [92]. Immobilization of V. vinifera cell suspension cultures with polyurethane foam matrices cause the enhancement of anthocyanins content [93]. In another study on Rubia tinctorum, immobilization of cell suspension cultures with sisal (a lignocellulose) produced 2- to 2.5-fold higher alizarin and purpurin content [95]. Cell cultures of Plumbago rosea were embedded in calcium alginate ((C??H??CaO??)n) and calcium chloride (CaCl2 ) and cause increased production of plumbagin [96].

Two-phase system

The two-phase cultivation method is also a useful in vitro tactic to enhance the generation of phytochemicals by plant tissue culture methods. In this system first phase allow cells to grow, while the second one provide a sink for the secondary products accumulation by reducing feedback inhibition of the desired compound [97]. Two phase culture systems are designed on the notion that a) avoid the snooping between product accretion and growth of cells, b) product loss is due to interaction among cells in suspension, enzymes released into the medium and c) due to minimization of down-stream process for product recovery [98]. Generally, the most important area of research is to study the methods which cause release of secondary products or extrusion from cells to the surrounding from where products can be recovered certainly. The most recognized example of two stage culture system is industrial production of shikonin utilizing L. erythrorhizon cell suspension culture adopted by a Japanese Mitsui Petrochemical Company [99]. Fujita et al., reported enhanced content of shikonin derivatives from L. erythrorhizon cell suspension culture in M-9 medium, however the biomass yield was poor in the same medium [100]. Therefore, this dual-phase culture system was opted in next study by using MG-5 medium for growth of cells and M-9 medium for production of shikonin derivatives [101]. In A. euchroma cell cultures, this technique was also used due to unlinking between behaviour growth and metabolites production [102]. In L. erythrorhizon, shikonin yield was increased 2-3 -fold by adopting two phase system which was treated with low energy ultrasound [36].

BIOREACTOR CULTIVATION OF NATURAL COLORANTS

‘Bioreactor’ is a type of vessel that is generally used for growing cell or organ cultures at higher scale. Bioreactors provide controlled environment e.g. temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, substrate etc. for the growth of cells and tissues to maximize their biomass or metabolic productivity. Over other cultivation systems, bioreactor has advantage as it enables fast growth, uniform mixing and absorption of nutrients, easy scalability as well as reduced cost and cultivation period. Additionally, the bioreactors cultivation allows a high degree of automation under submerged environment [103]. Owing to the specific morphology as well as physiology of in vitro cells or tissues, the availability of nutrients is a crucial aspect swaying both their growth and secondary metabolite production [104]. Different culture conditions like inoculum age and density, sucrose concentration, medium strength and volume, pH, temperature, light intensity, aeration and agitation in liquid medium need to be optimized to reach bioreactor level. The precise control of mass transfers for dissolved oxygen and nutrients is critical factor for submerged cultivation [103]. Besides the process parameters, the mode of cultivation and bioreactor design also affect the production of phytoconstituents.

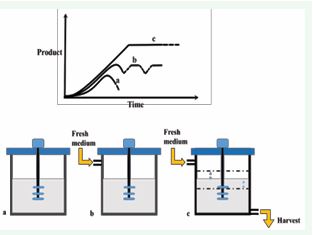

Types of cultivation system

Similar to fermentation technology, mostly plant cell and tissue culturist also deployed batch, fed batch and continuous type of cultivation systems for the accumulation of target compounds. In batch culture, sterilized medium and aseptic cultures are inoculated at the beginning and product is collected at the end of the culture period [104]. However, in continuous process, freshly prepared medium is continually added and product with spent medium are extracted from the bioreactor at the same rate. Fed-batch cultivation uses the combination of both batch and continuous systems. Here, nutrients are added continuously to the bioreactor to support the improved yields and products are harvested after the completion of the cycle [105] [Figure 8].

Figure 8 Different modes of cultivation in bioreactor a) batch, b) fed batch, c) continuous.

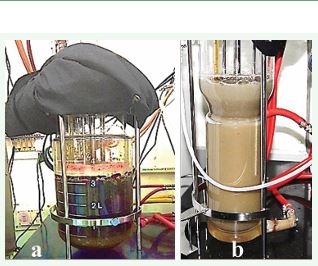

Types of bioreactors used in plant cell and tissue culture

In plant tissue cultures,different types of bioreactors have been used i.e. gas phase and liquid phase. In gas phase bioreactors organ cultures experience exposure of sterile air containing a mixture of gasses and nutrients in the form of droplets. Among these kinds of reactors, mist bioreactor was found more beneficial to get high azadirachtin content in hairy roots of Azadirachta indica [106], and trickle-bed bioreactors are reported to achieve high biomass yield up to 14 L [107]. In liquid phase bioreactors, cultures are suspended in liquid medium and includes rotating drum, bubble column, stirrer tank and airlift [Figure 9],

Figure 9 Bioreactor in plant tissue culture a) pigment production in stirred tank and b) biomass accumulation in airlift bioreactor.

bioreactors [108]. Nowadays, balloon type bioreactor has been explored for the production of phytoconstituents using in vitro cultures. Determining the suitable bioreactor system generally depends on plant cell and tissue type and its requirements with respect to shear sensitivity, dissolved oxygen, foaming and mixing attributes. Besides shake flask cultures, the pigment production is also reported by deploying different kinds of bioreactor systems [Table 2],

Table 2: Types of bioreactors used for the production of plant derived pigments.

|

Pigment type |

Plant species |

Explant used |

Culture type |

Medium used |

References |

|

Naphthoquinones |

Arnebia euchroma |

leaf, root |

Cell suspension |

MS+10.0 μM BAP +5.0 μM IBA |

37 |

|

Lithospermum erythrorhizon |

seedlings |

Cell suspension |

LS +10-6 M IAA+ 10-5 M kinetin |

34, 35 |

|

|

Impatiens balsamina |

leaf |

root cultures |

Gamborg’s B5 |

40 |

|

|

Arnebia euchroma |

cotyledons |

Adventitious roots |

- |

39 |

|

|

Anthraquinones |

Rudgea jasminoides |

ex vitro leaves |

cell suspension culture |

½ MS + 0.55 µM myo-inositol, 0.31 µM thiamine-HCl, 8 nM nicotinic acid+5 nM pyridoxine-HCl, 0.82 µM cysteine, 5% coconut water and 87.6 µM sucrose |

68 |

|

Polygonum multiflorum |

in vitro root explant |

cell suspension culture |

MS+1.0 mg/L 2,4-D+0.5 mg/L TDZ+100 µM L-glutamine |

47 |

|

|

Gynochthodes umbellate |

adventitious roots |

cell suspension culture |

MS +2.0 mg/L IAA |

69 |

|

|

Anthraquinones |

Morinda royoc |

in vitro roots |

Root culture |

MS+5.7 µM of IAA |

48 |

|

Morinda citrifolia |

in vitro leaf explant |

Adventitious roots |

MS+0.5 mg/L TDZ+ 5.0 mg/L IBA |

44 |

|

|

Daucus carota |

leaf explants |

cell suspension culture |

MS+ 8.88 µM BAP + 5.37 µM NAA + 20.0 mM: 37.6 mM NH4NO3 to KNO3 ratio |

57 |

|

|

Bridelia retusa |

stem tips and leaf explants |

cell suspension culture |

MS+2.0 mg/L 2,4-D and 2.5 mg/L BAP |

59 |

|

|

Daucus carota |

taproot and hypocotyl |

hairy root culture |

½MS |

70 |

|

|

Raphanus sativus |

root segments |

adventitious roots |

½MS + 0.5 mg/l IBA |

60 |

|

|

Flavonoids |

Astragalus missouriensis |

- |

cell suspension culture |

MS+ 1 mg/L NAA+ 2 mg/l kinetin+6% sucrose |

62 |

|

Centella asiatica |

leaf explants |

callus culture |

MS+2.0 mg/L 2,4-D |

71 |

|

|

Ginkgo biloba |

embryo |

callus culture |

MS+2.0 mg/L NAA + 1.0 mg/L BAP |

63 |

|

|

Ficus deltoidea |

leaf explant |

cell suspension culture |

MS+ Gamborg B5 vitamins +2.0 mg/L picloram + 1 mg/L kinetin |

66 |

|

|

Hypericum perforatum |

leaf |

adventitious root culture |

½ MS medium + B5 vitamins+ 1.0 mg/L IBA+ 0.1 mg/L kinetin, 3% sucrose+ 5:25 mM NH4+/NO3− |

65 |

|

|

Genista tinctoria |

in vitro shoots |

hairy root culture |

SH |

72 |

through cell and organ cultures. Jiao-wang et al., also used A. euchroma cell suspension culture and obtained 14.26% (dry weight) total shikonin derivatives from 10 L bioreactor [109]. In another study, scale up experiments were performed in 2L periodically submerged airlift bioreactor in which immobilized A. euchroma cell culture was used for production of shikonin [110]. Similarly, transgenic Nicotiana tabacum callus culture suspended in liquid medium were also allowed to grow in 2L stirred tank bioreactor for the production of anthocyanin with optimum growth at 3% inoculum density with 14 days of culture period [17]. Furthermore, Zhong et al., deployed cell suspension cultures of Perilla frutescens in 2.6 L stirrer bioreactor for production of anthocyanin and reported the effect of irradiation, and oxygen supply on overall productivity [111]. Subsequently, effect of shear forces on these cultures was also studied in 5L rotating drum reactor [112]. Furthermore, numerous investigations have also been conducted to understand the impact of inoculum density on growth as well as metabolic productivity during bioreactor cultivation. Interestingly, higher inoculum reported to have poor growth of cultures, probably due to early nutritional deficit in cultivation medium. According to some reports, plumbagin has been synthesized and accumulated in a 2L air sparged bioreactor using hairy root cultures of Plumbago rosea under optimized condition [113]. Research carried out by Gangopadhyay et al., revealed the effect of elicitation with chitosan and MeJA in elevating the plumbagin production in hairy roots of Plumbago indica under bioreactor cultivation process [114].

Pigment Extraction from Plants

After synthesis, to extract the pigments from tissues/ cells, fresh plant cultures harvested from the medium must be dried to remove the excess water content in the tissues by using blotting sheets. It is a preventative measure to keep the sample free of microbiological activity and extending its shelf life.

Key factors affecting pigment extraction

Followings are the key factors that affect extraction of pigments from plant parts:

- Solvent type

- Particle size of the raw material

- Physicochemical properties of the pigment

- Solid (sample) to liquid (solvent) ratio

- Extraction temperature and time period

Pigment extraction methods

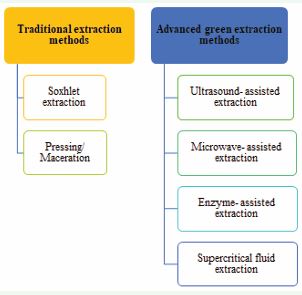

As a matter of fact, plants, microbes, and insects are the sources of the natural coloring agents or pigments that are frequently used in food applications [121], dominated by plant sources. Pigments are traditionally extracted from plant residue using solvent extraction. The downsides of solvent extraction are its adverse effects on the environment and human health, long processing time, limited extract yield, and high solvent consumption [122]. Nowadays, advanced green extraction methods like ultrasound, pulsed electric field, microwave, pressurized, and supercritical fluid extraction have been used in several studies on the extraction of various types of plant pigments [123-127]. Figure 10.illustrates the classification of pigment extraction methods into traditional and advanced approaches.

Figure 10 Classification of pigment extraction methods.

Conventional pigment extraction methods

(a) Soxhlet extraction: This approach involves pulverizing the sample thoroughly and placing it in a permeable sack or “thimble” made of cellulose or filter paper, which is subsequently put inside the thimble chamber of the Soxhlet apparatus. Upon heating, the solvent evaporates in the sample funnel, condense in the condenser, and then flow backwards. The procedure continues until the liquid content return into the bottom vessel after it passes through the siphon arm [128]. When it comes to solvent requirements, soxhlet extraction is less demanding than maceration. But highly pure extraction solvents are required in this system, which may raise the cost. In comparison to more recent green extraction techniques like supercritical fluid extraction, this process does not appear to be beneficial to the environment and could exacerbate the pollution issue [129].

(b) Pressing/ Maceration: A plant specimen is ground up and blended with a solvent to obtain crude pigments. The mixture is then put in a separator and stirred or agitated periodically. After completion of the procedure, the mixture is filtered, and the residue is either centrifuged or compressed using an automated press to continue the extraction process with a fresh diluent. The process is complete once the solvent becomes colorless [130].

Advanced pigment extraction methods

(a) Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE): The recovery of natural pigments from plants can be improved through ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE). It is a leading-edge environment friendly method that has several advantages. [131]. UAE stands out as the most efficient method due to its ease of use, requires minimal energy, and is inexpensive to install and maintain. [132]. The application of ultrasonic waves (inaudible to human hearing (20 KHz- 10 MHz)) hasten the extraction by increasing the solvent- plant source’s cell matrix coupling through periodic cavitation and rupture of bubbles [133]. The solvent can easily enter into the plant tissue and dissolve the required component, owing to the acoustic energy conveyed by pressure waves which results in oscillatory motion of molecules in the solvent [134]. Pulsed ultrasonic application is far more effective than continuous ultrasound treatment because it enhances extract yield without degrading the bioactive chemicals [135]. The cavitation phenomenon and the extract yield are greatly impacted by the solvent selection along with the parameters of the ultrasonic equipment [136].

(b) Microwave-Assisted Extraction: In order to achieve an increased temperature and mass transfer rate, microwave-assisted extraction primarily relies on the thermodynamic impact of radiations. The extraction efficiency is boosted by the faster heating and absorption of microwave radiation occured by a higher solvent polarity. The main benefits are specificity, homogeneous heating, speed and efficacy. In a research, maximum amount of betacyanin (17.12 mg/g dry mass) was extracted when the microwave power is 800 W for 3 minutes [137].

(c) Enzyme-Assisted Extraction: As a biological reaction catalyst, the enzyme breaks down the plant cell wall and cell matrix, which promotes the extraction of component into the solvent, speeds up the extraction process, and boosts yield. Enzyme-assisted extraction can use enzymes including cellulase, hemicellulase, ligninase, pectinase, and amylase. High productivity, gentle reaction conditions, great specificity, and quick extraction times are considered the benefits of this extraction technique. Zhao et al., looked into the best circumstances to use cellulase and pectinase to extract astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis [138]. After six hours at 45°C, pH 5.0, with 1.0% cellulase, the astaxanthin content was found 67.15%. However, at pH 4.5 and 55°C, the astaxanthin content was 75.30 % after the treatment of 0.08% pectinase.

(d) Supercritical Fluid Extraction: With this technology, a component (extract) can be isolated from its mixture (matrix) by using a supercritical fluid as an extracting agent. The main classes of supercritical solvents are alcohols, aromatics, hydrocarbons, and certain gases. CO2 is the most widely used supercritical fluid because it is inexpensive, readily available, safe, and capable of separating compounds that are susceptible to heat without leaving any solvent residue after extraction. Polyphenols were extracted from white grape seeds at 40°C, using various pressures, CO2 tresses, and co-solvent proportions [139]. Major factors in any developing technology’s success are its cost effectiveness and sustainability. In case of plant pigment extraction, the above mentioned green advanced methods are more effective and sustainable. While the aforementioned extraction techniques offer benefits, they also have drawbacks, such as high equipment costs and low equipment utilization. To address these drawbacks, multiple-research employed a sequence of the aforesaid extraction techniques. As a result, multiple procedures can be used for pigment extraction rather than being restricted to just one.

APPLICATIONS OF PLANT PIGMENTS IN VARIOUS SECTORS

Role of plant derived pigments in pharmaceutics is well known and reported by several researchers. Besides this, these natural, safe and human- friendly colorants has several other applications as stated below.

Plant pigments in food sector

When it comes to how consumers see, choose, and accept different food items, color is a key factor. The market is expanding at a rapid pace due to consumer demand for organic and nutritious food products. Consequently, the food industry plays a significant role in the colorant industry’s trade [140]. Natural pigments are becoming more and more popular among scientists as a safer alternative to synthetic ones because of concerned factors like biological safety, pharmacological benefits, and the nutritional value of food colors [141]. In terms of functioning and health, use of coloring agents for plant based meat that come from natural sources is more beneficial as compared to animal myoglobin. However, due to their chemical unsteadiness, which is influenced by pH, temperature, light, and oxygen, use of plant pigments may not be as common in the industry. Therefore, using them for various food products is highly challenging. Though alternative methods have been investigated, encapsulation serves as the most effective way to stabilize plant pigments and boost their utilization in the food industry [142].

Plant pigments in cosmetics

The majority of colors employed in skincare products are artificial dyes or colors. Azo dyes, xanthone, indigoid and other synthetic dyes are some of the frequently used ones in makeup. Subsequent research revealed that artificial dyes had toxic and carcinogenic impact [143], and are also discovered to be carbon emitting. Therefore, use of beauty products containing natural pigments get started by people [144]. Plant materials like stems, barks, leaves, fruits, flowers, pollen and seeds are used to make natural colors. Natural sources of color include henna, teak, annatto, spice paprika, carrots and turmeric etc.

Plant pigments in textiles

Natural colorants are experiencing a faster rate of growth globally than the overall color market [145]. One of the best examples used as a colorant or biomordant in textile dyeing is turmeric. Textiles made from cotton were treated with turmeric powder and colored with black carrot leaf extract. The textiles evaluated, shown greater color intensity when treated with turmeric biomordant, according to the findings presented by Batool et al. [146]. It was best to employ two percent of the plant pigment to dye cotton, silk, and wool, with different mordants for shades of color [147]. In additional researches, cotton and silk fibers dyed with annatto seed extract demonstrated good durability characteristics.

Plant pigments in leather industry

Tanning is one of the most crucial steps in the leather manufacturing process that turns this fragile material into a durable one. For this purpose, synthetic tanning substances comprising phenols or hydrocarbons are widely employed. Plant-derived pigments may become more significant now-a-days due to the pressing need to lessen the negative effects of chemicals used in the tanning and dying of leather fabrics. A lot of research is going to find natural alternatives to synthetic and chemical compounds that are not as good for the surroundings or human health. Several examples of plant pigments as leather tanning agents include the use of colorants derived from Coreopsis tinctoria flower petals [148], enhanced dye affinity between Terminalia chebula Retzius and leather through the use of an enzymatic post-tanning procedure [149], and both sweet potato and black chokeberry colorants combined with silver nanoparticles [150,151]. Besides these applications, coloring paper for dfferent purposes and in printing sector, pigments obtained from plants are in high demand. Introduction of some other advanced uses of natural pigments like fluroscent cell imaging, coatings of different artifacts and plastic accessories, painting (wall paints and canvas paints), biosensors and dye sensitized solar cells etc. in the market is also in progress. These new areas of applications are making a strong demand for the production of plant pigments from plant tissue culture techniques in less time with maximum yield.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

‘Plants’ are life-line of mankind, be it food, medicine & personal care products, clothes, energy fuel and/or construction material and serving the societies since time immemorial. Nevertheless, we have to understand that these are renewable bioresources, but not unlimited. Renewable resources, because they can grow fast, replaced through cultivation and their part specific use may help in avoiding their complete destruction. However, it doesn’t mean that plants are immortal. There are number of factors i.e. habitat destruction owing to urbanization, commercial gains led over-exploitation, climate change, changing human life-style like demand for natural, increasing population and natural calamities like COVID-19 that reaffirmed the value of plants in health and wellbeing. Furthermore, advances in evidence based scientific validation of phytopharmaceuticals led to unprecedented demand in plant-based products or phytoconstituents. Hence, we have to develop sustainable production system that not only can meet the demand of plant-based industries but will also be able to cope up with changing environments. In this regard, the concept of phytofactories can be of immense importance, where large scale cultivation can be done using lab scale protocols developed by deploying plant cell and tissue cultures. Like biochemical engineering aspects established in fermentation technology, plant specific technologies also needs to be developed rapidly. Modern molecular biology techniques need to be used for understanding the induction, proliferation and multiplication behaviour of cell and tissue cultures. The translation of optimized lab scale bioprocess at industrial level is also critical and the only factor that can lead to a commercially feasible system. The design and manufacturing of plant cell and tissue friendly bioreactors, downstream processing and automation based on engineering concepts in overall bioprocess will further pave the way for development of phytofactories. In addition, the establishment of pigment specific cell or organ culture lines, patent regimes, IPR protection and safety regulations needs to be strengthened at institutional as well as government level to boost research.

CONCLUSION

Plant pigments are coloured organic compounds playing important role in growth and development of plants. Besides their use as colourants, these pigments are also used in pharmaceutical formulations. Huge industrial demand for such pigments led to overexploitation of natural resources and therefore, immediate step needs to be taken for the restoration of our plant bioresources. In this regard, biotechnological approaches based on plant cell and tissue culture demonstrated good potential for large scale production. These phytofactories can be a feasible and sustainable means for phytochemicals production and meet the growing demand for naturals. Using these non-destructive techniques, a large number of phytopigments i.e. naphthoquinones, anthraquinones and flavonoids are produced from in vitro cultures of L. erythrorhizon and Arnebia species; P. multiflorum and Ginkgo biloba, respectively. However, the plant/cell/ tissue specific factors like explant & genotype, medium and hormones, culture environment and scale-up must have to be standardized at lab scale before improving the phytochemical productivities. In relation to optimization of various physicochemical parameters, pigment extraction methods also holds immense importance for maximizing the harvest with minimum wastage. Green extraction methods need refined solvent type, optimized extraction time and temperature and a balanced ratio of solute to solvent. Similar to fermentation technology, plant cell, tissue and organ culture systems also needs a revolution with support from disciplines like biochemical engineering, molecular biology, bioinformatics and chemical technology for commercial success.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are thankful to the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Govt. of India for funding the work vide Grant No. MLP-204. JD is thankful to CSIR, India for providing junior and senior sresearch fellowship from 2017-2022. MSD is thankful to UGC, New Delhi, India for providing the UGC-Junior and Senior Research Fellowship. JD and MSD are also thankful to AcSIR, Ghaziabad, India for Ph.D. enrolment. This manuscript represents 5939 as CSIR-IHBT communication number.

CREDIT AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT

JD and MSD have contributed equally and performed manuscript writing and editing of the original manuscript. SB conceived & designed the study, edited and reviewed the original manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Sudhakar P, Latha P, Reddy PV. Phenotyping crop plants for physiological and biochemical traits. Phenotyping Crop Plants. Physiol Biochem Trait. 2016: 1-172.

- Swami SB, Ghgare SN, Swami SS, Shinde KJ, Kalse SB, Pardeshi IL. Natural pigments from plant sources: A review. J Pharm Innov. 2020; 9: 566-574.

- Upadhyay RK. Plant pigments as dietary anticancer agents. Int J Green Pharm. 2018; 12: 93-107.

- López-Cruz R, Sandoval-Contreras T, Iñiguez-Moreno M. Plantpigments: Classification, extraction, and challenge of their application in the food industry. FABT. 2023; 16: 2725-2741.

- Negi A. Natural Dyes and Pigments: Sustainable Applications and Future Scope. Sus Chem. 2025; 6: 23.

- Lyu X, Lyu Y, Yu H, Chen W, Ye L, Yang R. Biotechnological advances for improving natural pigment production: A state-of-the-art review. Bioresources and bioprocessing. 2022; 9: 8.

- Dikshit R, Tallapragada P. Chapter 3 - Comparative study of natural and artificial flavoring agents and dyes in handbook of food bioengineering, natural and artificial flavoring agents and food dyes. Academic Press. 2018; 83-111.

- Expert Market Research. 2023

- Markets and Markets. 2023.

- Market Research Report

- Cosmetic Pigments Market. 2022.

- Natural Food Color Market Embraces Clean Labels and Health-Driven Innovations. 2025.

- The Global Market for Carotenoids. 2025

- Lycopene Food Colors Market. 2025.

- Fujita Y, Tabata M. Secondary metabolites from plant cells: pharmaceutical applications and progress in commercial production. In: Green CE, Somers DA, Hack-ett WP, Biesboer DD (eds) PTC. 1987. Alan R. Liss, New York.

- Dicosmo F, Misawa M. Plant cell and tissue culture: alternatives for metabolite production. Biotechnol Adv. 1995; 13: 425-435.

- Appelhagen I, Wulff-Vester AK, Wendell M, Hvoslef-Eide AK, Russell J, Oertel A, et al. Colour bio-factories: towards scale-up production of anthocyanins in plant cell cultures. Metab Eng. 2018; 48: 218-232.

- Devi J, Kumar R, Singh K, Gehlot A, Bhushan S, Kumar S. In vitro adventitious roots: a non-disruptive technology for the production of phytoconstituents on the industrial scale. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2021; 41: 564-579.

- Choi SM, Son SH, Yun SR, Kwon OW, Seon JH, Paek KY. Pilot-scale culture of adventitious roots of ginseng in a bioreactor system. PCTOC. 2000; 62: 187-193.

- Kitanov GM, Pashankov PP. Quantitative investigation on the dynamics of plumbagin in Plumbagio europea L. roots and herb by HPLC. Pharmazie. 1994; 49: 462.

- Hussain MS, Fareed S, Ansari S, Akhlaquer RM, Zareen AI, MohdS. Current approaches toward production of secondary plant metabolites. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2012; 4: 10-20.

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962; 15: 473- 497.

- Gamborg OL, Miller RA, Ojima K. Nutrient requirements of suspension cultures of soyabean root cells. Exp Cell Res. 1968; 50: 151-158.

- 24.White PR. Potentially unlimited growth of excised plant callus in an artificial nutrient. Am J Bot. 1939; 26: 59-64.

- Linsmaier EM, Skoog F. Organic growth factor requirements of tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1965; 18: 100-127.

- Nitsch JP. Experimental androgenesis in Nicotiana. Phytomorphol. 1969; 19: 398-404.

- Schenk RU, Hildebrandt AC. Medium and techniques for induction and growth of monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous plant cell cultures. Can J Bot. 1972; 50: 199-204.

- Lloyd G, McCown B. Commercially feasible micro-propagation of mountain laurel Kalmia latifolia by use of shoot tip culture. Comb Proc Int Plant Prop Soc. 1980; 30: 421-427.

- Bharati AJ, Bansal YK. In vitro production of flavonoids: a review. World J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014; 3: 508-533.

- Shi M, Liao P, Nile SH, Georgiev MI, Kai G. Biotechnological exploration of transformed root culture for value-added products. Trends Biotechnol. 2021; 29: 137-149.

- Hahn EJ, Kim YS, Yu KW, Jeong CS, Paek KY. Adventitious root cultures of Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer and ginsenoside production through large scale bioreactor systems. J Plant Biotechnol. 2013; 3: 1-6.

- Murthy HN, Hahn EJ, Paek KY. Adventitious roots and secondary metabolism. Chin J Biotechnol. 2008; 24: 711-716.

- Malik S, Bhushan S, Sharma M, Ahuja PS. Biotechnological approaches to the production of shikonins: a critical review with recent updates. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2014; 36: 1-14.

- Tabata M, Mizukami H, Hiraoka N, Konoshima M. Pigment formation in callus cultures of Lithospermum erythrohizon. Phytochem. 1974; 13: 927-932.

- Mizukami H, Konoshima M, Tabata M. Variation in pigment production in Lithospermum erythrorhizon callus cultures. Phytochem. 1978; 17: 95-97.

- Lin L, Wu J. Enhancement of shikonin production in single and two- phase suspension cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon cells using low energy ultrasound. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2001; 78: 81-88.

- Malik S, Bhushan S, Sharma M, Ahuja PS. Physico-chemical factors influencing the shikonin derivatives production in cell suspension cultures of Arnebia euchroma (Royle) Johnston, a medicinally important plant species. Cell Bio Int. 2013; 35: 153-158.

- Ravi Kumar, Sharma N, Mali S, Bhushan S, Upendra Kr Sharma, Devla Kumari, et al. Cell suspension culture of Arnebia euchroma (Royle) Johnston - a potential source of naphthoquinone pigments. J Med Plant Res. 2011; 5: 6048-6054.

- Hu J, Leng Y, Jiang Y, Ni S, Zhang L. Effect of light quality on regeneration and naphthoquinones accumulation of Arnebia euchroma. Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2019; 13: 353-360.

- Sakunphueak A, Panichayupakaranant P. Effects of donor plants and plant growth regulators on naphthoquinone production in root cultures of Impatiens balsamina. PCTOC. 2010; 102: 9-15.

- Hook ILI. Naphthoquinone contents of in vitro cultured plants and cell suspensions of Dionaea muscipula and Drosera species. PCTOC. 2001; 67: 281-285.

- Chang HC, Lu CY, Chen CC, Kuo CL, Tsay HS, Agrawal DC. Plumbagin, a plant-derived naphthoquinone production in tissue cultures of Drosera spatulata Labill. Biotechnol. 2019; 18: 24-31.

- Hagendoorn MJM, Van der Plas LHW, Segers GJ. Accumulation of anthraquinones in Morinda citrifolia cell suspensions. In: Schripsema J, Verpoorte R. (eds) Primary and Secondary Metabolism of Plants and Cell Cultures III. Springer, Dordrecht. 1994.

- Baque MA, Hahn EJ, Paek KY. Growth, secondary metabolite production and antioxidant enzyme response of Morinda citrifolia adventitious root as affected by auxin and cytokinin. Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2010; 4: 109-116.

- Abdullah MA, Ali AM, Marziah M, Lajis NH, Ariff AB. Establishment of cell suspension cultures of Morinda elliptica for the production of anthraquinones. PCTOC. 1988; 54: 173-182.

- Jasril, Lajis NH, Abdullah MA, Ismail NH, Ali AM, Marziah M, et al.Anthraquinones from cell suspension culture of Morinda elliptica. Nat. Pro. Sci. 2000; 6: 40-43.

- Thiruvengadam M, Rekha K, Rajakumar G, Lee TJ, Kim SH, Chung IM. Ehanced production of anthraquinones and phenolic compounds and biological activities in the cell suspension cultures of Polygonum multiflorum. Int J Mol Sci. 2016; 17: 1912.

- Janetsy B, Josep C, Maribel R, Maria B, Oscar C, Yudelsy A, et al. Anthraquinones from in vitro root culture of Morinda royoc L. PCTOC. 2008; 94: 181-187.

- Park SU, Lee SY. Anthraquinone production by hairy root culture of Rubia akane Nakai: influence of media and auxin treatment. Sci Res Essays. 2009; 4: 690-693.

- Huang B, Lin H, Yan C, Qiu H, Qiu L, Yu R. Optimal inductive and cultural conditions of Polygonum Multiflorum transgenic hairy roots mediated with Agrobacterium rhizogenes R 1601 and an analysis of their anthraquinone constituents. Phcog Mag. 2014; 10: 77-82.

- Jackman RL, Yada RY, Tung MA, Speers RA. Anthocyanins as food colorants- review. J Food Biochem. 1987; 11: 201.

- Miniati E, Coli R. Anthocyanins: not only color for foods, In: Francis,F. J. (ed.) Papers Presented at the 1st International Symposium on Natural Colorants for Foods, Nutraceuticals, Beverages and Confectionery, Hamden, Connecticut, The Herald Organization. 1993.

- Constabel F, Shyluk JP, Gamborg OL. The effect of hormones on anthocyanin accumulation in cell cultures of Haplopappus gracilis. Planta. 1971; 96: 306-316.

- Matsumoto T, Nishida K, Noguchi M, Tamaki E. Some factors affecting the anthocyanin formation by Populus cells in suspension culture. Agr Biol Chem. 1973; 37: 561-567.

- Sugano N, Hayashi K. Possible scheme for the compounds in by studies by nobuhiko biosynthesis of anthocyanin and a carrot aggregen as indicated tracer experiments on anthocyanins, LVIII. Bot Mag Tokyo. 1967; 80: 481- 486.

- Yamakawa T, Kato S, Ishida K, Kodama T, Minoda Y. Production of anthocyanins by Vitis cells in suspension culture. Agr Biol Chem. 1983; 47: 2185-2191.

- Saad KR, Parvatam G, Shetty NP. Medium composition potentially regulates the anthocyanin production from suspension culture of Daucus carota. 3 Biotech. 2018; 8: 134.

- Siatka T. Production of anthocyaninsin callus cultures of Angelica archangelica. Nat Prod Commun. 2018; 13: 1645-1648.

- Aswathy JM, Sumayya SS, Lawarence B, Kavitha CH, Murugan K. Purification, fractionation and characterization of anthocyanin from in vitro culture of Bridelia retusa (L.) Spreng. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2018; 80: 52-64.

- Betsui F, Tanaka-Nishikawa N, Shimomura K. Anthocyanin production in adventitious root cultures of Raphanus sativus L. cv. Peking koushin. Plant Biotechnol. 2004; 21: 387-391.

- Yang Y, He F, Yu L, Ji J, Wang Y. Flavonoid accumulation in cell suspension cultures of Glycyrrhiza inflata Batal under optimizing conditions. Naturforsch. 2009; 64: 68-72.

- Ionkova I. Optimization of flavonoid production in cell cultures of Astragalus missouriensis Nutt. (Fabaceae). Pharmacogn Mag. 2009; 4: 92-97.

- Shui Y, Cheng W, Zhang N, Sun F, Xu L, Li Y, Liao CH. Production of flavonoids and terpene lactones from optimized Ginkgo biloba tissue culture. Not Bot Horti Agrobo. 2014; 42: 88-93.

- Gai QY, Jiao J, Luo M, Wei ZF, Zu YG, Ma W, et al. Establishment of hairyroot cultures by Agrobacterium rhizogenes mediated transformation of Isatis Tinctoria L. for the efficient production of flavonoids and evaluation of antioxidant activities. PLoS One. 2015; 10: e0119022.

- Cui XH, Chakrabarty D, Lee EJ, Paek KY. Production of adventitious roots and secondary metabolites by Hypericum perforatum L. in a bioreactor. Bioresour Technol. 2010; 101: 4708-4716.

- Haida Z, Syahida A, Ariff SM, Maziah M, Hakiman M. Factors affecting cell biomass and flavonoid production of Ficus deltoidea var. kunstleri in cell suspension culture system. Sci Rep. 2019; 9: 9533.

- Gabr AMM, Sytar O, Ghareeb H, Brestic M. Accumulation of amino acids and flavonoids in hairy root cultures of common buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum). Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2019; 25: 787-797.

- Oliveira MC, Negri G, Salatino A, Braga MR. Detection of anthraquinones and identification of 1,4-naphthohydroquinone in cell suspension cultures of Rudgea jasminoides (Cham.) Müll. Arg. (Rubiaceae). Revista Brasil Bot. 2007; 30: 167-172.

- Pillai AR, Gangaprasad. Adventitious root derived callus culture and anthraquinone production in Gynochthodes umbellata (L.) Razafim. & B. Bremer (Rubiaceae). Int J Res Anal Rev. 2018; 5: 2349-5138.

- Barba-Espín G, Chen ST, Agnolet S, Hegelund JN, Stanstrup J, Christensen JH, et al. Ethephon-induced changes in antioxidants and phenolic compounds in anthocyanin-producing black carrot hairy root cultures. J Exp Bot. 2020; 1-16.

- Tan SH, Musa R, Ariff A, Maziah M. Effect of plant growth regulators on callus, cell suspension and cell line selection for flavonoid production from pegaga (Centella asiatica L. urban). Am J Biochem Biotechnol. 2010; 6: 284-299.

- ?uczkiewicz M, Kokotkiewicz A. Co-cultures of shoots and hairy roots of Genista tinctoria L. for synthesis and biotransformation of large amounts of phytoestrogens. Plant Sci. 2005; 169: 862-871.

- Eibl R, Ebil D. Plant cell-based bioprocessing. Biomedical and lifesciences. In: Eibl R, Ebil D, Portner R, Catapano G, Czermak P(Eds) Cell and tissue reaction engineering, Springer, Berlin, 2008: 315-356.

- Radman R, Sacz T, Brucke C. Elicitation of plant and microbial system. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2003; 37: 91-102.

- Rahmat E, Kang Y. Adventitious root culture for secondary metabolite production in medicinal plants: a review. J Plant Biotechnol. 2019; 4: 143-157.

- Fukui H, Tani M, Tabata M. Induction of shikonin biosynthesis by endogenous polysaccharides in Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell suspension cultures. Plant Cell Rep. 1990; 9: 73-6.

- Fu XQ, Lu DW. Stimulation of shikonin production by combined fungal elicitation and in situ extraction in suspension cultures of Arnebia euchroma. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1999; 2: 243-246.

- Ge F, Wang X, Zhao B, Wang Y. Effects of rare earth elements on the growth of Arnebia euchroma cells and the biosynthesis of shikonin. Plant Growth Regul. 2006; 4: 283-290.

- Krishnan SRS, Siril EA. Elicitor and precursor mediated anthraquinone production from cell suspension cultures of Oldenlandia umbellata L. IJPSR. 2017; 7: 3649-3657.

- Cai Z, Kastell A, Mewis I, Knorr D, Smetanska I. Polysaccharide elicitors enhance anthocyanin and phenolic acid accumulation in cell suspension cultures of Vitis vinifera. PCTOC. 2012; 108: 401-409.

- Baque MA, Elgirban A, Lee EJ, Paek KY. Sucrose regulated enhanced induction of anthraquinone, phenolics and flavonoids biosynthesis and activities of antioxidant enzymes in adventitious root suspension cultures of Morinda citrifolia (L.). Acta Physiol Plant. 2012; 34: 405- 415.

- Wang J, Qian J, Yao L. Enhanced production of flavonoids by methyl jasmonate elicitation in cell suspension culture of Hypericum perforatum. Bioresour Bioprocess. 2015; 2: 2-9.

- Plata N, Konczak-Islam I, Jayram S. Effect of methyl jasmonate and p-coumaric acid on anthocyanin composition in a sweet potato cell suspension culture. Biochem Eng J. 2003; 14: 171-177.

- Namdeo AG, Jadhav TS, Rai PK, Gavali S, Mahadik KR. Precursor feeding for enhanced production of Secondary metabolites. Pharmacogn Rev. 2007; 1: 227-231.

- Qu J, Zhang W, Yu X. A combination of elicitation and precursor feeding leads to increased anthocyanin synthesis in cell suspension cultures of Vitis vinifera. PCTOC. 2011; 107: 261-269.

- Shinde AN, Malpathak N, Fulzele DP. Enhanced production of phytoestrogenic isoflavones from hairy root cultures of Psoralea corylifolia L. using elicitation and precursor feeding. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng. 2009; 14: 288-294.

- Edahiro J, Nakamura M, Seki M, Furusaki S. Enhanced accumulation of anthocyanin in cultured strawberry cells by repetitive feeding of L-phenylalanine into the medium. J Biosci Bioeng. 2005; 99: 43-47.

- Cai Z, Kastell A, Knorr D, Smetanska I. Exudation: an expanding technique for continuous production and release of secondary metabolites from plant cell suspension and hairy root cultures. Plant Cell Rep. 2012; 31: 461-477.

- Brodelius P, Pedersen H. Increasing secondary metabolite production in plant cell culture by redirecting transport. Trends Biotechnol. 1993; 11: 30-36.