Neutralization of the Venom of 2 North American Rattlesnake Venoms by a Hyperimmune Equine Plasma product in Mice

- 1. Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences, Oklahoma State University, USA

- 2. Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, Oklahoma State University, USA

- 3. Department of Statistics, Oklahoma State University, USA

Abstract

Antivenom treatment of domestic animals is becoming more common following introduction of more veterinary products. The aim of this study was to investigate the ability of a new hyperimmune equine origin antivenina to neutralize the effects of two North American rattlesnake venoms. LD50s were established for two rattlesnake venoms [Western Diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox) and Mojave rattlesnake (Crotalus scutulatus)] using a murine model and standard methods. An ED50 was established for the product for both venoms using these LD50s. Venom (5x the LD50) and hyperimmune plasma (5 varying doses) were combined and incubated for 30 minutes and administered intraperitoneally. Sickness scores and time to death were recorded during the study period and compared amongst groups in the ED50 studies. The LD50 for the Western Diamondback rattlesnake was 5.567ug/g and Mojave rattlesnake was 0.122ug/g. The ED50 for the Western Diamondback rattlesnake was 16.4mls/kg and the Mojave rattlesnake was 17.3mls/kg. Envenomated mice treated with higher doses of hyperimmune plasma had significantly lower sickness scores (p < 0.05) and lived longer (p < 0.05). The equine hyperimmune plasma product tested in this study was successful at neutralizing lethality up to 48 hours and reducing morbidity when tested against 5 times the LD50 of both venoms in this mouse model.

Keywords

• Antivenom

• Equine

• Rattlesnake

• Venom

Citation

Gilliam LL, Moser DK, Ritchey JW, Payton ME, Cassidy J (2017) Neutralization of the Venom of 2 North American Rattlesnake Venoms by a Hyperimmune Equine Plasma product in Mice. J Pharmacol Clin Toxicol 5(3):1077.

INTRODUCTION

Rattlesnake envenomation is not uncommon in domestic animals and is often clinically significant. Clinical signs in these animals range from mild tissue swelling to severe coagulopathies, extensive tissue swelling, tissue necrosis and death. The severity of clinical signs can depend on many factors such as the amount of venom injected, the species of snake, time of year, age of the snake and other environmental factors as well as the health of the patient envenomated. Rattlesnake venoms are a complex mixture of proteins that work together to destroy tissue in an effort to digest their prey. Some rattlesnake venoms, such as the Mojave rattlesnake (Crotalus scutulatus), also contain neurotoxins to assist in immobilizing prey. Bites from these snakes can be much more rapidly fatal and require immediate intervention.

In the horse, the most common bite locations are the muzzle or distal limbs. Limb envenomations in horses can lead to secondary complications such as lameness and subsequent supportive-limb laminitis. These complications may result in a prolonged recovery and even loss of use in some cases. Horses are obligate nasal breathers therefore bites to the muzzle resulting in extensive tissue swelling that occludes the nasal passages are life threatening. In the dog the most common bite location is the head, followed by the limbs. In either species, secondary coagulopathies can be severe and life threatening. The mortality in domestic animals can be quite variable. Some of the variability may be due to the broad range of treatments that are administered in veterinary practice. Although antivenom has long been the treatment of choice for pit viper envenomation in humans [1], its use in veterinary medicine is not as well established. In human medicine, antivenom has been shown to reduce not only mortality but also morbidity [2]. In contrast to people, some literature suggests that antivenom may not be beneficial following pit viper envenomations in veterinary patients, and increases both the cost of treatment and the length of hospitalization [3]. This increased cost of treatment often limits its use in veterinary patients and a cost effective alternative is needed.

There are three products licensed for use in treating envenomation in veterinary patients in addition to the product tested in this study. The product that has been used the longest in veterinary medicine is an equine derived lyophilized serum polyvalent whole IgG productb . Venoms used in the production of this product are Crotalus adamanteus, Crotalus atrox, Crotalus terrificus, and Bothrops atrox. A newer product on the veterinary market is an equine derived polyvalent F(ab)2 productc . Venoms used in the production of this product are Bothrops alternatus or Bothrop sdirorus, Lachesis muta, Crotalusduris susterrificus or Crotalus simus. Additionally there is a hyperimmune equine plasma productd that can be used to treat rattlesnake envenomation in the horse. This product is produced using Crotalus atrox, Crotalus scutulatus scutulatus and Crotalus viridis viridis (Table 1).

Table 1: Veterinary envenomation treatment options. North American snakes are underlined.

| Veterinary Envenomation Treatment Options |

Immunizing Snakes | Form of Antivenom |

| RATTLERANTIVENI |

Crotalusatrox, Crotalusadamanteus, Crotalusviridisviridis, Crotalusscutulatusscutulatus |

Whole plasma, equine derived, polyvalent |

| Antiveni |

Crotalusadamanteus, Crotalusatrox, Crotalusterrificus, Bothropsatrox |

Serum origin, equine derived, lyophilized, polyvalent, whole IgG |

| VenomVe |

Bothropsalternatus, Bothropsdirorus, Lachesis muta, Crotalusdurissusterrificus or Crotalussimus |

Serum origin, equine derived, polyvalent, F(ab)2 |

| Antigen Select Equine HI Plasma (*not labeled as an antivenom) |

Crotalusatrox, Crotalusscutul atusscutulatus,Crotalusviridi sviridis |

Whole plasma, equine derived |

Although there are marked similarities in venom composition across species of rattlesnakes, there are also important

a) RTLRTM, Mg Biologics, Ames IA

b) Antivenin™, Boehringer-Ingelheim, St. Joseph, MO

c) VenomVet™, MT Venom, LLC, Canoga Park, CA

d) Antigen Select Equine HI Plasma (options Western Diamondback, Prairie, and/or Mojave rattlesnakes), Lake Immunogenics, Ontario, NY

differences and not all antivenoms neutralize all venoms equally. For example, a much higher dose of antivenin crotalidae polyvalent was required to neutralize Crotalus helleri, a rattlesnake species similar to Crotalus virdis viridis

Although there are marked similarities in venom composition across species of rattlesnakes, there are also important differences and not all antivenoms neutralize all venoms equally. For example, a much higher dose of antivenin crotalidae polyvalent was required to neutralize Crotalus helleri, a rattlesnake species similar to Crotalus virdis viridis [4]. Recent work utilizing proteomics, antivenomics and venomics has shown that there may be venom composition differences that make a patient more or less likely to respond to a given antivenom treatment [5,6], indicating all antivenoms may not be created equally.

The present study evaluated the ability of an equine origin polyvalent plasma antivenin producta produced using Crotalus atrox, Crotalus adamanteus, Crotalus viridis viridis, and Crotalus scutulatus scutulatus to neutralize Crotalus atrox and Crotalus scutulatus scutulatus venoms including the ability to decrease morbidity using an LD50/ED50 murine model. Although alternative methods are being sought, the LD50/ED50 murine model remains the most standard method for assessing antivenom efficacy [1]. Our hypotheses were that this equine hyperimmune plasma producta would effectively neutralize both venoms characterized by a dose-dependent increase in survival time and decrease in morbidity measured by clinical sickness scores.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Venoms

Lyophilized venom from Crotalus atrox and Crotalus scutulatus scutulatusd was used throughout this study. Stock solution of the venom was made at the concentration of 10mg/ml. The lyophilized venom was measured using a gram scale and 10mg was reconstituted with 1ml of physiologic saline. The 10mg/ml solution was then aliquoted into 100ul aliquots and frozen at -20°C. These aliquots were then used to make serial dilutions as needed during the remainder of the study. All dilutions were made using physiologic saline. All stock solution was frozen a minimum of 24 hours prior to making serial dilutions. Stock solution was allowed to thaw at room temperature before making serial dilutions. Stock solution was only subject to one freeze/thaw cycle. All serial dilutions were used immediately and were not frozen.

Hyperimmune plasma

The producta is a hyperimmune equine plasma. The snake venoms used in the production of this product were Crotalus atrox (Western Diamondback rattlesnake), Crotalus adamanteus (Eastern Diamondback rattlesnake), Crotalus viridis viridis (Prairie rattlesnake), and Crotalus scutulatus scutulatus (Mojave rattlesnake). The plasmaa was received in 100ml bags. A filter sete was used to aseptically remove 5ml aliquots that were then frozen at -20°C until use. Plasma was allowed to thaw at room temperature prior to use. All plasma was frozen a minimum of 24 hours prior to use and was only subject to two freeze/thaw cycles.

e) Blood Set, Hospira, Lake Forest, IL

Lethal dose (LD50)

Equal numbers of 18-20g, male and female micef of the ICR (CD-1) strain were used in this study. Mice were group housed by sex 5 per cage in individually ventilated cagesg on 1/8 inch corn cob beddingh in a room dedicated to mouse colonies. Mice were fed a commercially available, standard dieti free choice and given access to ad libitum water. A 12 hr light: dark cycle was maintained with no twilight. Mice were given a minimum 3 day acclimation period prior to entering the study. At the end of the acclimation period mice were randomly assigned to a treatment group and marked using non-toxic colored markers.

For humane reasons in compliance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee’s request, analgesia was administered to all mice (control and treatment groups) throughout the study. The analgesia protocol for all mice was; buprenorphinej (0.05 mg/kg subcutaneously) and meloxicamk (5 mg/kg subcutaneously) 12 hours prior to receiving each treatment and every 12 hours after until they died or were euthanized. All mice still surviving at 48 hours after treatment were euthanized using a CO2 chamber.

Each lyophilized venom [Western Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox) and Mojave Rattlesnake (Crotalus scutulatus)], was reconstituted with physiologic saline to 10 mg/ml, aliquoted in 100ul aliquots and frozen for 24 hours at -20°C. Aliquots were allowed to thaw at room temperature and further dilutions were made using physiologic saline to an estimated 5X LD50 based on previous publication and injected IP (intraperioteneal) into a single mouse using a 25 gauge 5/8 inch needle, with a maximum total liquid volume of 80 ml/kg mouse weight. The mouse was observed hourly for 48 hours, a sickness score was assigned at each hourly observation and the time of death was noted for fatal doses. Dosages were either reduced by 50% or increased by 50% until the dosages were known for a fatal dose and a nonfatal dose. A range of 4 doses that ranged between the fatal and nonfatal doses was determined (6 doses total). Six mice were then assigned to each one of the 6 dose groups. Doses were produced starting with the initial 10 mg/ml aliquots of venom and using physiologic saline as diluent. The venom dilutions were made so that the maximum volume of liquid injected in each mouse would not exceed 80ml/kg. Each venom dilution dose was injected IP into 6 mice using a 25 gauge 5/8 inch needle. Mice were observed for 48 hours and the time of death was noted for fatal doses. Each venom group had a control group of mice receiving saline alone. Mice that were alive at the end of the study period (48 hours) were humanely euthanized using a carbon dioxide chamber.

e) Blood Set, Hospira, Lake Forest, IL

f) Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN and Houston, TX

g) One Cage, Lab Products, Seaford, DE

h) Harlan-Teklad, Madison, WI

i) Laboratory Rodent Diet 5001, PMI Feeds, St. Louis, MO

j) Buprenex®, Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Richmond, VA

k) OstiLox™, VETone, Boise, ID

Venom neutralization dose (ED50)

The neutralizing dose of an Hyperimmuneplasmaa was estimated using a challenge dose of venom that was 5X the calculated LD50 for each venom. Five times the LD50 for each venom was mixed with a dose (4ml/kg) of polyvalent equine hyperimmuneplasmaa and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. Next the mixture was administered to one mouse intraperitoneally as described above. The mouse was observed hourly and assigned a sickness score for 48 hours or until death. Dosages were either reduced by 50% or increased by 50% until the dosages were known for a dose where the mouse survived and a dose where the mouse did not survive. A range of 5 doses of the hyperimmuneplasmaa expected to provide a range of neutralization that included a protective dose and a non protective dose were calculated.

Venom dilutions were made as described above and a dose of venom was calculated for each mouse to equal 5x the previously calculated LD50 for each venom (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2: Mouse Sickness Score.

| Sickness Score | Clinical Description |

| 1 | Bright, alert, responsive or quiet, alert, responsive Either grooming or eating |

| 2 | Quiet, alert, responsive No eating or grooming in >6hrs or at least one of the following: --tachypnea, lethargy, squinting, hunching, ruffled hair Still able to socialize and active when being caught |

| 3 | >1 of the following: tachypnea, lethargy, squinting, hunching, ruffled hair Does not resist touch or being caught |

| 4 | Dead |

Table 3: LD50 values dosed on aug/g basis.

| Venom | Lower 95% Limit |

Upper 95% Limit |

|

| Mojave Rattlesnake | 0.122 | 0.110 | 0.134 |

| Western Diamondback Rattlesnake |

5.567 | 4.990 | 6.150 |

Each of the 5 doses of hyperimmuneplasmaa was mixed with 5 times the estimated LD50 challenge dose (ug/g) of each of the venoms individually and the mixtures were incubated at 37ºC for 30 minutes. Control mice received a dose of hyperimmuneplasmaa (4 ml/kg) with no venom challenge. Each dose group, including control, consisted of 6 mice. One control mouse received venom alone to ensure the lethality of the dose for each venom group.

The mice were observed hourly for 48 hours by blinded observers. Mice were assigned a sickness score ranging from 0 to 4 (Table 2). The sickness score was derived under the direction of the University Laboratory Animal Veterinarian based upon basic mice behaviors. Mice surviving at 48 hours were humanely euthanized using a CO2 chamber.

Two of the authors and 5 assistants were trained in mouse behavior and observed the mice hourly throughout the study. The behavior was monitored and recorded at each hour. Sickness scores from 0 to 4 were assigned to each mouse hourly as well. Time of death was noted as close to the hour as possible to calculate survival time. All of these evaluators were blinded throughout the study.

This study was approved by the Oklahoma State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (VM-13-34).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Binary response regression assuming the probit model was used to estimate the LD50 and ED50 doses. The highest sickness score for each mouse for the duration of the study was determined and the mean of the high score for the six mice in each dosing group was calculated. These mean sickness scores were then used for analysis. Sickness scores were evaluated using analysis of variance methods (ANOVA). Means are reported and if significant in the overall comparisons in the ANOVA, pair wise comparisons are made. Survival times were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier statistics. A significance level of 0.05 was used for all comparisons.

RESULTS

The LD50s generated indicate the estimated weight of venom that is lethal to 50% of mice. They are shown in Table 3. The calculated ED50s indicate the estimated volume of hyperimmuneplasmaa required to neutralize venom and provide protection from death in at least 50% of mice. They are shown in Table 4.

Table 4: ED50 values dosed on aug/g basis.

| Venom | Challenge Dose of Venom Administered (ug/g) |

Lower 95% Limit | Upper 95% Limit | |

| Mojave Rattlesnake | 0.6113 | 0.0173 | 0.0162 | 0.0183 |

| Western Rattlesnake | 27.834 | 0.0164 | 0.0144 | 0.0189 |

The hyperimmuneplasmaa was able to neutralize both venoms tested in this study. There was 100% mortality in control mice that received venom alone.

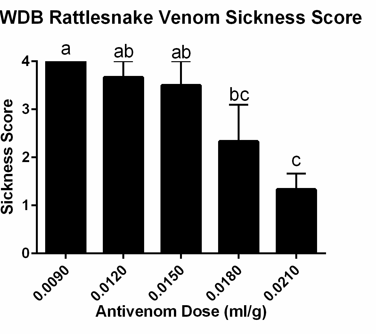

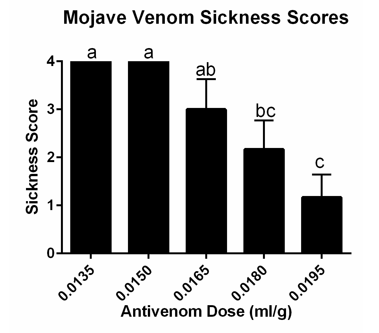

Mice receiving an hyperimmune plasma/venom mixture containing the highest dose of hyperimmuneplasmaa in each venom group had significantly lower mean sickness scores (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1 Mean Sickness Scores in mice receiving hyperimmune plasma + Western Diamondback rattlesnake venom. Letters show statistically significant differences between groups (p=0.0030).

Figure 2 Mean Sickness Scores in mice receiving hyperimmune plasma + Mojave rattlesnake venom. Letters show statistically significant differences between groups (p=0.0004).

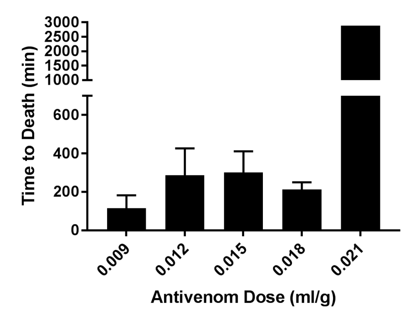

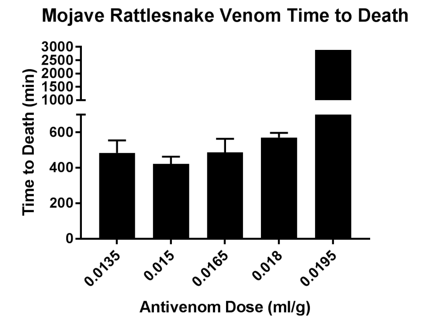

Time to death was also analyzed for each treatment group. Mice receiving the highest dose of hyperimmuneplasmaa were significantly more likely to survive than mice receiving lower doses of hyperimmuneplasmaa in both venom groups (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3 Time to Death in mice given hyperimmune plasma + Western Diamondback rattlesnake venom. Mice receiving highest dose of hyperimmune plasma had stastically siginificantly longer survival times (p=0.0008).

Figure 4 Time to Death in mice given hyperimmune plasma + Mojave rattlesnake venom.Mice receiving highest dose of hyperimmune plasma had stastically siginificantly longer survival times (p = 0.003).

No adverse effects were noted in control mice receiving hyperimmuneplasmaa alone.

DISCUSSION

The ability of an equine hyperimmuneplasmaa to neutralize two North American rattlesnake venoms was tested in this study. This product is unique in that it is the only plasma product with the antivenom label and it is produced using all North American rattlesnakes [Western Diamondback (Crotalus atrox), Eastern Diamondback (Crotalus adamanteus), Mojave (Crotalus scutulatus scutulatus) and Timber (Crotalus horridus)]. There may be some benefit to using a product that is produced using venoms from the species of snake that actually bit the animal. Although rattlesnake venoms are very similar, they do have differences. There are documented differences in response to antivenom depending on the type of snake that caused the bite [4-6].

Being a plasma product may offer some benefit to animals suffering from coagulopathy secondary to rattlesnake envenomation. However; coagulopathies can occur through many different mechanisms so the benefit of plasma would be dependent upon the cause of the coagulopathy.

There are also inherent risks to administering a plasma product. Any time foreign proteins are administered to an animal there is a risk for anaphylaxis. This product would carry minimal risk for horses, but could carry more significant risk for dogs. Peer reviewed safety data would be useful in evaluating the risk versus benefit of this product in a dog. Safety data gathered during licensing process did not indicate major adverse effects (personal communication Sarah Anthony). Lower total protein containing products such as Fab1 and Fab2 products have a lower risk of allergic reaction than whole IgG antivenom products [7]. A whole plasma product would carry more risk than any of these products due to the presence of more foreign proteins. The fewer foreign proteins, the less the risk of an adverse reaction.

LD50 studies have been performed previously on the venoms used in this study. Our findings were similar to those found by Sanchez et al. [8]. Interestingly, the route of administration in the Sanchez study was intravenous whereas the intraperitoneal route was used in this study. A comparison of IV versus IP administration of viper venom to mice showed that LD50s are approximately three times higher when the venom is given IV versus IP [9].With cobra venoms however, there was very little difference in the LD50s when venom is given IP versus IV [8]. The variation in clinical outcome secondary to route of venom administration is thought to be, at least in part, due to the size of the molecules in the venom [9]. The most toxic components in cobra venom are very small molecules allowing them to rapidly enter circulation from the IP route and therefore resulting in less difference in the two routes of administration [9]. To the authors’ knowledge this work has not been done with the venoms used in this study. Subjectively, it was noted that mice receiving Mojave rattlesnake (Crotalus scutulatus) venom took longer to experience the onset of effects and showed very minimal to no clinical signs immediately after envenomation; whereas mice receiving the Western Diamondback (Crotalus atrox) venom showed more immediate signs of depression, hunching and lack of activity. When evaluating LD50s it is important to know what route of administration was used.

The authors’ understand that there are limitations to the conclusions drawn from this type of study. An obvious limitation is that mice are not the target species for use of this product. There are inherent risks of species specific response differences whether due to physiologic, anatomic, metabolic or other factors. True challenge studies in the target species; however are difficult because of the suffering induced by rattlesnake venom, making murine models and in vitro models increasingly more popular and justifiable. Murine models do not allow for dosage estimations to be made and do not give an adequate picture of what safety issues may arise with a given product in the target species. Even when using murine models, humane treatment of the animals must be taken into account. Analgesics were provided for all mice, including controls, during this study. One of the analgesics was a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (meloxicam) which could have effects on the mechanism of action of the venom and hyperimmune plasma. The medication was given to all mice including control mice to try to account for any treatment effect.

During the ED50 study, the venom was mixed with the hyperimmune plasma and then incubated prior to giving it to mice. This is the standard method of testing neutralizing ability of antivenom. Unfortunately this does not mimic natural envenomation and dosing information cannot be extrapolated from this study. Additionally, the venoms used to challenge mice in this study were the same venoms that were used in the manufacturing process of the hyperimmune plasma which could give an efficacy bias. Using venoms of the same species but from a different source may offer a more robust challenge to the antivenin product.

CONCLUSION

Neutralization of lethality remains the best method of determining efficacy of an antivenom product. The equine hyperimmune plasma tested in this study was successful at neutralizing lethality up to 48 hours when tested against 5xthe LD50 of both venoms. Higher doses of this antivenom product were also able to reduce morbidity in mice when compared to lower doses. No adverse effects were noted in any mice receiving hyperimmune plasma alone. While the premixed venom/ hyperimmune plasma murine model may not exactly mimic natural envenomation, it does establish that this producta is capable of neutralizing lethality of the venoms tested up to 48 hours as well as reducing morbidity in mice. Peer reviewed studies in target species are needed to confirm safety of the product as well as dosing and efficacy in these species. This product offers the option of cost effective antivenom to be used in veterinary patients as well as antivenom that is produced using all North American rattlesnake venoms. The increased availability of antivenom for veterinary patients may result in decreased morbidity and mortality similar to what has been seen in human medicine.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding for this study was provided by MgBiologics, Inc. The authors thank Stacia Sullivan, Markie Schiller, Kristen Borsella, Tyler Caron, and Cassandra Cullins for technical assistance.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Lyndi Gilliam, Jerry Ritchey and Mark Payton conceived and designed the experiment. Lyndi Gilliam, Darla Moser and Jordan Cassidy performed the experiment. Mark Payton and Lyndi Gilliam analyzed the data. Lyndi Gilliam, Jerry Ritchey and Darla Moser composed the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

This study was funded by the producer of the hyperimmune plasma. The founding sponsor had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to publish the results.