Polyphyllin I Inhibits the Proliferation of Bladder Cancer Cells by Down-regulating ADAR1

- 1. Yunnan University of Chinese Medicine, China

- 2. Kunming Medical University, China

- 3. State Key Laboratory of Phytochemistry and Sustainable Utilization of Plant Resources in Western China, China

- #. The authors have equal contribution to the paper.

Abstract

Objective: To investigate the molecular mechanism of Polyphyllin I (PPI) inhibits the proliferation of bladder cancer cells through intervening ADAR1 pathway.

Methods: It has been confirmed whether PPI can modulate ADAR1, thereby inhibiting the proliferation of bladder cancer cells both in vivo and in vitro.

Results: PPI inhibited the proliferation of bladder cancer cells in a dose-, time-, and concentration-dependent manner, significantly down-regulating the protein level of ADAR1 while increasing the levels of ZBP1 in vitro. Following the knockdown of the ZBP1 gene, PPI was unable to down-regulate the protein level of ADAR1; conversely, PPI could not increase the protein level of ZBP1 after the ADAR1 gene was overexpressed. In the animal experiment, PPI significantly inhibited the growth of tumors in Xenograft mice with bladder cancer cells, down-regulating the protein level of ADAR1 and up-regulating the levels of ZBP1, RIPK3, NLRP3, Caspase-1, and GSDMD.

Conclusion: PPI may inhibit the proliferation of bladder cancer cells by suppressing the activity of ADAR1 and promoting the expression level of ZBP1 protein.

Keywords

• PPI

• ADAR1

• ZBP1

• Bladder cancer

Citation

cLiu Z, Chen R, Tan Z, Zhao H, Wei Z, et al. (2025) Polyphyllin I Inhibits the Proliferation of Bladder Cancer Cells by Down-regulating ADAR1. J Pharmacol Clin Toxicol 13(2):1193.

INTRODUCTION

Bladder cancer is a prevalent malignancy within the urinary tract, consistently ranking among the top 10 most common cancers worldwide, with an estimated 550,000 new cases and 200,000 fatalities reported each year [1,2]. While the 5-year survival rate for patients with bladder cancer stands at 77.1%, this figure drops dramatically to a mere 4.6% once the disease has metastasized [3,4]. Furthermore, it is noted that approximately 25% of patients newly diagnosed with bladder cancer present with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC), where cancer cells have penetrated the muscularis propria of the bladder wall [5,6]. The current standard of care for muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) involves neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) and radical cystectomy (RC) [7]. Furthermore, the intravesical administration of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is intended to stimulate a local immune response to inhibit the proliferation of bladder cancer cells; however, this treatment fails in approximately 40% of patients. As a result, there is an urgent need for the development of innovative therapeutic approaches for bladder cancer [8]. Cell pyroptosis, a distinct mode of cell death, is orchestrated by the gasdermin (GSDM) protein family. Upon detection of exogenous or endogenous signals, inflammatory cells initiate inflammasome formation, followed by GSDM cleavage, which triggers the release of proinflammatory cytokines and cellular contents. This cascade of events culminates in the demise of the inflammatory cells [9]. Notably, recent research has identified cell pyroptosis as a promising therapeutic avenue for antitumor strategies [10]. Z-DNA binding protein 1 (ZBP1), is a potent innate immune sensor that plays a role in regulating innate immune responses and initiating multiple inflammatory cell death signaling pathways within PANoptosis, which encompasses pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis [11]. The Zα domain of ZBP1 can activate key molecules that regulate cell pyroptosis, namely NLRP3, ASC, and Caspase-1, thereby activating the NLRP3 inflammasome. Upon sensing stimulatory signals, NLRP3 recruits ASC and Caspase-1, which further cleaves and activates GSDMD. The activated GSDMD translocates to the cell membrane and promotes pore formation, leading to the release of cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 [12], ultimately resulting in inflammatory cell death. Besides ZBP1, ADAR1 is the only other protein known to contain the Zα domain [13]. The Zα domain of ZBP1 detects viral or endogenous Z-RNA, which leads to the interaction between the receptor-interacting protein homotypic interaction motif (RHIM) domain of ZBP1 and the corresponding RHIM domain of RIPK3, driving cell death [14-16]. The absence of ADAR1 results in increased expression of ZBP1, triggering extensive inflammasome activation and PANoptosis [17]. Conversely, the absence of ZBP1 hinders the activation of cGAS-STING signaling and the priming of CD8 T cells in tumor cells post radiotherapy [18]. ADAR1 can prevent ZBP1 from recognizing Z-RNA [19], and the loss of ADAR1 function facilitates ZBP1 mediated PANoptosis [20]. Consequently, ADAR1 suppresses ZBP1 signaling, which may promote cancer development. The creation of new drugs that can inhibit ADAR1 function or directly activate ZBP1 could represent innovative strategies for cancer treatment [21,22].Chinese traditional herbal medicines, abundant in anti inflammatory and anti-cancer compounds, can suppress the proliferation of malignant tumor cells and mitigate the side effects of chemotherapy [23-25]. For instance, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), which targets the laminin receptor (Lam 67R), has demonstrated significant efficacy in treating prostate cancer [26], Ginsenoside Rh2 inhibits P-glycoprotein (P-gp) activity, reversing multidrug resistance in tumor cells [27], Curcumin induces autophagy, enhancing apoptotic cell death [28], Berberine can inhibit tumor progression and may serve as a safe, effective, and cost-effective treatment for cancer patients [29], and Shikonin, among others, exhibits synergistic effects with chemotherapy drugs [30].Based on the anti-tumor targets of ADAR1 and ZBP1, the present study conducted virtual screening of a small molecule compound library from locally accessible traditional Chinese medicines in Yunnan Province, China, using the computer software AutoDockTools. Polyphyllin I (PPI) scored highly in this screening. PPI, a steroidal active saponin component of Paris polyphylla found in Yunnan Province, is widely used for the treatment of snake bites, sore throat, and various malignancies [31]. However, the specific anti-tumor molecular mechanism of PPI remains unclear. This study found that PPI may inhibit the proliferation of bladder cancer cells by regulating the ADAR1/ZBP1 pathway in both in vitro and in vivo experiments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Human bladder cancer cells J82 and RT112, as well as the mouse bladder cancer cell line MB49 and the 293T cell line, were purchased from the National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures. Experimental mice (C57BL/6J) were obtained from Hunan SJA Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. Polyphyllin I (PPI) (CAS: 50773-41-6) was purchased from Biochempartner (Shanghai, China), and the ADAR1 inhibitor CBL0137 (CAS: 1197996-80 7) was also acquired from Biochempartner (Shanghai, China). Protein antibodies against ADAR1 (24330-1-AP), ZBP1 (13285-1-AP), RIPK3 (17563-1-AP), and GSDMD (20770-1-AP) were purchased from Proteintech (wuhan, china). Antibodies against NLRP3 (also known as NALP3) (bs-6655R) and Caspase-1 (bs-10743R) were obtained from Bioss (Beijing, China). Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (C04001-050) was purchased from VivaCell BIOSCIENCES (Shanghai, China). The Penicillin-Streptomycin Solution (Pen-Strep-Solution) (C3420-0100) was also acquired from VivaCell BIOSCIENCES (Shanghai, China). The Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (11668-019) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. The adeno-associated virus 9 (AAV9) for overexpression of ADAR1 (86541-1) was sourced from GeneChem (Shanghai, China), and the ZBP1 siRNA (siRNA-460, siRNA-527, siRNA-1088) was obtained from GENERAL BioL (Anhui, China). The ZBP1 sequence was as follows:

ZBP1 (human) siRNA-527, GGGAAUGAGGACAGCAAAA

TTUUUUGCUGUCCUCAUUCCCTT;

ZBP1(human)siRNA-460, AGGAAGACAUCUACAGGUUT

AACCUGUAGAUGUCUUCCUTT;

ZBP1 (human) siRNA-1088 CCAGAGAAUCCACAUGAAA

TTUUUCAUGUGGAUUCUCUGGTT

Methods

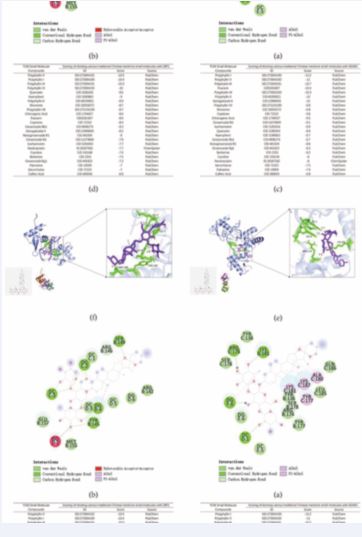

Computer-Aided Virtual Screening: To obtain the 2D structural active ingredient SDF files of small molecule compounds from traditional Chinese medicines, one can access the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/). These files will serve as the ligand files, which will then undergo minimum binding energy optimization using Chem3D version 23.1.1. The protein receptor files for ADAR1 (PDB ID: 1QBJ) and ZBP1 (PDB ID: 3EYI) canbe retrieved from the PDB database (https://www.rcsb. org/). The protein receptors will be processed to remove water and adjust residue ligands using PyMOL software. Molecular docking and result calculation will be conducted using AutoDockTools version 1.5.7, developed by the Olson Laboratory at The Scripps Research Institute. The binding affinity between the receptor and ligand will be evaluated based on the binding energy levels obtained from the molecular docking results. A binding energy lower than −5 kJ/mol indicates that the target small molecule compound from traditional Chinese medicine has a certain degree of binding activity with the docking targets ADAR1 or ZBP1. The lower the binding energy, the better the docking effect. PPI demonstrated the highest docking scores with both ADAR1 and ZBP1 proteins (Figure 1). Consequently, PPI was chosen for further visual docking analysis using PyMOL software. The visual docking results were then analyzed using Discovery Studio 2019 software.

Figure 1 PPI showed the better docking scores by computer-based virtual screening targeting the dual targets ZBP1 and ADAR1 using the AutoDock tool. (a) and (b) displayed the scoring results for each small molecule from traditional Chinese medicines. (c) and (d) presented the three-dimensional docking images of PPI with ADAR1 and ZBP1, respectively. (e) and (f) illustrated the binding sites of PPI with ADAR1 and ZBP1 proteins, respectively.

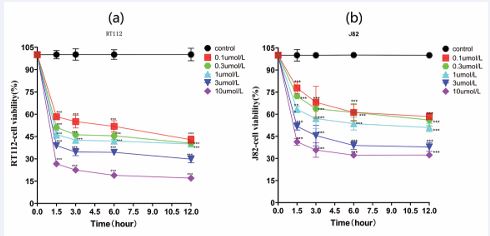

The Influence of Polyphyllin I on the Viability of Bladder Cancer Cells: Bladder cancer cell lines RT112 and J82 were cultured in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 95% air. The cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 2x10^4 cells per well during their logarithmic growth phase. The inhibitory effect of Polyphyllin I (PPI) on bladder cancer was examined at 1.5 hours, 3 hours, 6 hours, and 12 hours post-treatment using thiazolyl blue (methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium, MTT). The concentrations of PPI tested were 0.1 µM, 0.3 µM, 1 µM, 3 µM, and 10 µM. To each well, 10 µl of a 5 mg/ml MTT solution was added. After 4 hours, DMSO was added, and the plates were allowed to react for 10 minutes. The absorbance values were measured at a wavelength of 570 nm using the Enzyme- linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and the data were processed and statistically analyzed.

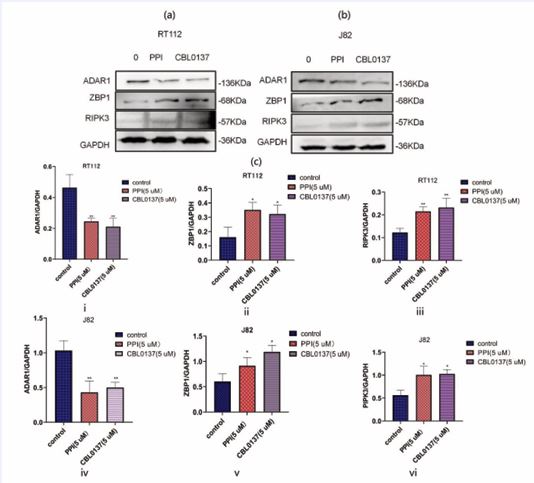

The Impact of PPI on ADAR1 Protein Expression in Bladder Cancer Cells: RT112 and J82 cells were resuspended in complete medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and cultured in a cell incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells in the logarithmic growth phase, exhibiting over 80% confluence, were digested with 0.25% trypsin. Following thorough pipetting to disperse the cells, they were seeded into cell culture plates. The cells were then divided into three groups: a model group (no treatment), a Polyphyllin I group (with a final drug concentration of 5µM), and a positive control group (treated with CBL0137 at a final drug concentration of 5µM). After 24 hours of Polyphyllin I treatment, the cells were collected for Western Blotting analysis.

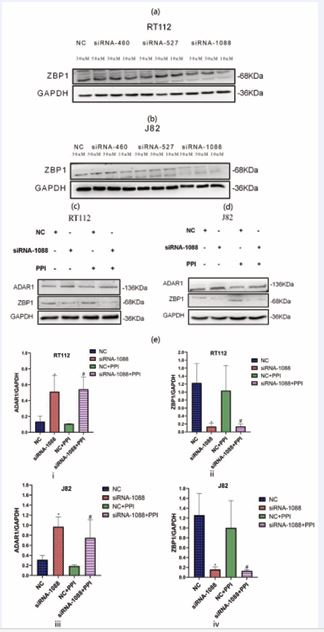

Gene Silencing or Overexpression Studies in Cellular Models: RT112 and J82 cells were seeded in a 12-well plate at a density of 2×105 to 3×105 cells per well during their logarithmic growth phase. The following day, upon achieving over 90% cell confluence, siRNA targeting ZBP1 was added to each well: siRNA-ZBP1 empty vector, siRNA-ZBP1 460, siRNA-ZBP1 527, and siRNA-ZBP1 1088.The siRNA-empty vector concentration was 30 nM, while the other fragments were tested at three concentrations: 50 nM, 30 nM, and 10 nM. Following the transfection protocol outlined in the manual, Lipofectamine 2000 was utilized to introduce the various siRNA fragments into the bladder cancer cells. The cells were then incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 48 hours, the cells were harvested, and transfection efficiency was assessed using Western Blotting. After determining the most effective siRNA for transfecting ZBP1, the bladder cancer cells were replated in a 12-well plate and the subsequent groups were established: negative control, siRNA ZBP1, negative control+ PPI, and siRNA ZBP1 + PPI. Twenty-four hours post- plating, siRNA ZBP1 was introduced, and PPI was added 24 hours later. After an additional 24 hours, cell proteins were extracted and Western Blotting was performed.PRDX3-Flag plasmids, driven by the pGFAP promoter, were packaged into AAV9 for the overexpression of ADAR1. The AAV9 vectors were designed and produced by GeneChem (Shanghai, China). 293T cells were plated in a 12-well plate at a density of 7×104 cells per well during their logarithmic growth phase. When the cell confluence reached approximately 90%, AAV9-pGFAP empty vector and AAV9-pGFAP-ADAR1 were added to the negative control and ADAR1 overexpression groups, respectively. Simultaneously, the transfection reagent Lipofectamine 2000 was added and mixed, followed by incubation at 37°C for 12 hours. The following day, the medium was replaced with 5 ml of DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and double antibiotics, and the cells were cultured for an additional 48 hours. The first batch of medium containing viral particles was collected and stored at 4°C. The medium was then replaced with 5 ml of fresh medium, and after a further 72 hours, the medium containing viral particles was collected. The collected medium from both the 48-hour and 72-hour time points was centrifuged at 1250 rpm for 5 minutes, after which the precipitate was discarded and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 µm filter. The filtered medium was stored at -20°C or -80°C.RT112 and J82 cells were plated at a density of 20×104 to 30×104 cells per well in a 12-well plate during their logarithmic growth phase. When the cells reached approximately 90% confluence, the collected viral supernatant was added to infect the cells. Polybrene (hexadimethrine bromide) was then added to enhance infection. The following day, the medium was replaced with fresh medium and cultured for an additional 24 hours. Puromycin was added at a concentration of 1-2 µg/ ml for three days to select for successfully infected cells. The number and proportion of fluorescent cells were observed under an inverted fluorescence microscope. The culture of successfully selected cells was expanded, and the efficiency of ADAR1 overexpression was validated by Western Blotting. After confirming successful ADAR1 overexpression in RT112 and J82 bladder cancer cells, the following groups were set up: negative control, ADAR1 overexpression, negative control with PPI, and ADAR1 overexpression with PPI. The cells were plated and PPI was administered 24 hours later. After an additional 24 hours, the cell proteins were extracted and Western Blotting was performed for detection.

Establishment of a Mouse Model for Bladder Cancer Xenograft and Evaluation of PPI Intervention Therapy: To establish a mouse model for bladder cancer xenograft tumors, well-cultured MB49 bladder cancer cells were mixed with PBS and subcutaneously inoculated into each C57BL/6J mouse at a density of 6×103. When the transplanted tumor volume reached 80 mm3, the mice were divided into groups: control, low-dose PPI group (25 mg/kg), high-dose PPI group (80 mg/kg), and positive drug group (CBL0137, 30 mg/kg). Except for the control group, which was gavaged with a 0.5% CMC-Na solution, each treatment group received intervention therapy with the corresponding dose of PPI or CBL0137. The treatment lasted for 21 days, and the mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation under anesthesia. The preparation method of the PPI dosing solution was based on the literature on a microemulsion drug delivery system (PPI-SMEDDS) [32], with an optimal average drug loading of 4.03 ± 0.03 mg/g. In this study, a drug loading of 4 mg/g was used to prepare the PPI-containing nanoemulsion. The specific process is as follows: First, accurately weigh the total daily dose of PPI required. Calculate the total amount of SMEDDS needed based on a nanoemulsion drug loading of 4 mg/g (with an oil phase of 15.89%, emulsifier of 47.38%, and co-emulsifier of 36.73%). Dissolve PPI, Cremophor RH40 (emulsifier), and 1,2-propanediol (co-emulsifier) in ethyl oleate (oil phase) in the aforementioned proportions. Mix thoroughly with a glass rod. Gradually add the aqueous phase (water) while stirring. Stop adding when the solution becomes transparent and mix well. Additionally, accurately measure the daily dose of CBL0137 required for the positive drug group to avoid drug adherence to the walls of the container or leakage. Weigh, dissolve, and dilute the drug in an appropriate amount of 0.5% CMC-Na solution for one and a half days’ use. Measure the body weight and tumor volume of the mice every other day. The tumor volume was calculated using the formula V = ab2 / 2 (where a is the longest axis and b is the shortest axis). Following the experiment, the mice were humanely euthanized via cervical dislocation, and the tumor tissue samples were collected as follows: The tumor, complete with any associated blood clots or blood vessels, was meticulously dissected from the mice in physiological saline. Depending on the experimental requirements, portions of the tumor were excised. Half of the tumor tissue was finely minced and temporarily stored on ice, then preserved at -80°C for Western blot analysis. The remaining half of the tumor tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in the dark and processed for paraffin embedding within 48 hours. The embedded paraffin blocks were subsequently stored at room temperature. This animal experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Kunming Medical University in accordance with the Animal Care and Use regulations (Approval No: Kmmu20221563).

Western Blotting: To extract total protein from bladder cancer tissue or cells, the tissue was homogenized or digested in a mixture of RIPA lysis buffer and protease inhibitor at 4°C for 30 minutes. The supernatant was collected by centrifuging at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and the pellet was discarded. Protein concentration was measured using a BCA assay kit. Subsequently, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Bio-Rad) was performed, and the SDS gel was transferred onto a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% non fat milk powder at room temperature for 1 hour. The membrane was then incubated with primary antibodies against GAPDH (1:10,000), ADAR1 (1:1,000), ZBP1 (1:2,000), NLRP3 (1:1,000), Caspase-1 (1:1,000), and PIPK3 (1:2,000) overnight at 4°C. Afterward, the membrane was incubated with the corresponding secondary antibody for 1 hour. Finally, protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) system, and the optical density values were analyzed using Image Pro Plus 6.0 software. The blots were normalized using the GAPDH protein signal.

Immunohistochemical Analysis: The embedded paraffin blocks were sectioned at a thickness of 3 μm. The sections were treated with 3% H2 O2 for 10 minutes and then heated in 10 mM citrate buffer at 95°C for 15 minutes to retrieve antigens and inactivate endogenous peroxidase. Following this, the sections were blocked with 5% goat serum. Subsequently, the samples were incubated with primary antibodies ADAR1 (1:200) and ZBP1 (1:200) overnight at 4°C. After incubation with the corresponding secondary antibody (1:100) for 1 hour, the slides were washed and stained with diaminobenzidine (Solarbio). The nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin (Solarbio), and the slides were sealed with neutral resin. Finally, images were captured under a microscope. The immunohistochemical images were analyzed using the Color Deconvolution algorithm in the ImageJ® analysis program plugin to assess antibody expression levels. The degree of positive expression was calculated based on grayscale values and subjected to statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed and plotted using GraphPad Prism 9, SPSS 27.0, and ImageJ. The experimental data represented the mean values from at least three independent and repeated measurements. Quantitative data are presented as “mean ± standard deviation” ( x ±s). The data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the least significant difference (LSD) test. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

PPI showed the better docking scores by Computer Aided Virtual Screening

Figures 1a and 1b illustrated the docking scores of each small molecule from the traditional Chinese medicines of Yunnan Province, China. PPI exhibited higher docking scores with both ZBP1 and ADAR1, and was therefore selected for further molecular experiments. Figures 1c and 1d depicted the three-dimensional docking images of PPI with ADAR1 and ZBP1, respectively. The binding sites of PPI with the ADAR1 protein included DC-1, PG-6, ARG-174, and LYS-181 (e), while the binding sites of PPI with the ZBP1 protein included DG-4, DC-3, TYR-145, and SER-149 (f).

PPI inhibited the activity of bladder cancer cells in a time- and concentration-dependent manner

PPI was utilized to intervene in the bladder cancer cell lines RT112 and J82, and the proliferation activity of the bladder cancer cells was assessed using the MTT assay. As depicted in Figures 2a and 2b, in comparison to the control group, the cell viability of bladder cancer cells RT112 and J82 diminished significantly in a time- and drug concentration-dependent manner (*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001). The 12-hour IC50 value for RT112 was 0.162 µM, and for J82, it was 0.606 µM.

Figure 2 PPI inhibited the activity of bladder cancer cells in a time- and concentration-dependent manner. (a) The effect of PPI on the viability of RT112 cells. (b) The effect of PPI on the viability of J82 cells. Asterisks (*) denote statistical significance between the control group and the drug-treated group (*: p<0.05; **: p<0.01; ***: p<0.001).

PPI suppressed the expression of ADAR1 and elevated the levels of ZBP1 and RIPK3 proteins in bladder cancer cells

To further evaluate the mechanism of PPI’s anti bladder cancer activity, Western Blotting was employed for detection. As shown in Figures 3a and 3b, PPI significantly reduced the protein level of ADAR1 while increasing the levels of ZBP1 and RIPK3. These results suggest that PPI may inhibit the proliferation of bladder cancer cells by suppressing the activity of ADAR1 protein level and increasing the level of ZBP1 protein.

Figure 3 PPI inhibited the expression of ADAR1 and increased the expression levels of ZBP1 and RIPK3 proteins. a, b, and c showed the protein interference levels of PPI on ADAR1, ZBP1, and RIPK3, respectively, in bladder cancer cells RT112 and J82. Asterisks (*) indicate statistical significance between the control group and the drug-treated group (*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01).

PPI was unable to inhibit the protein level of ADAR1 after knocking down the ZBP1 gene in RT112 and J82 cells.

To verify whether PPI inhibits the proliferation of bladder cancer cells by inhibiting ADAR1 protein and increasing ZBP1 protein levels, this study conducted experiments to knock down the ZBP1 gene and overexpress the ADAR1 gene in bladder cancer cells. As shown in Figures 4a and 4b, the siRNA ZBP1 1088 exhibited better knockdown efficiency with increasing intervention concentrations after treating RT112 and J82 cells with siRNA ZBP1, and thus it was selected for further experiments. Figures 4c and 4d demonstrated that PPI was unable to suppress the protein level of ADAR1 in RT112 and J82 cells where the ZBP1 gene was knocked down.

Figure 4 PPI did not suppress the protein level of ADAR1 following siRNA mediated knockdown of ZBP1 in RT112 and J82 cells. Western Blotting experiments were conducted to confirm the screening efficacy of siRNA knockdown ZBP1 in RT112 and J82 cells (a, b). (c, d, e) illustrated the protein levels of ADAR1 and ZBP1 following PPI treatment in RT112 and J82 cells with ZBP1 knockdown. Asterisks (*) denote statistical significance between the negative control (NC) group and the siRNA ZBP1 group (*: p<0.05); the hash (#) indicates statistical significance when comparing the NC + PPI group to the siRNA ZBP1 + PPI group.

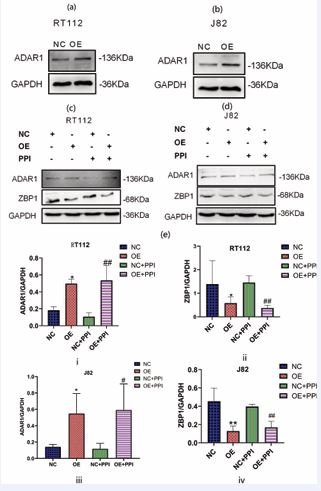

After overexpressing ADAR1 in RT112 and J82 cells, PPI was unable to increase the protein level of ZBP1

As depicted in Figures 5a and 5b, the protein level of ADAR1 in the overexpression group was significantly higher than that in the negative control group, indicating successful overexpression of ADAR1 in RT112 and J82 cells. As illustrated in Figures 5c and 5d, PPI was unable to increase the protein level of ZBP1 in RT112 and J82 cells with overexpressed ADAR1. Based on the aforementioned knockdown and overexpression results, it is speculated that PPI may inhibit the proliferation of bladder cancer cells by inhibiting the activity of ADAR1 and increasing the protein level of ZBP1.

Figure 5 PPI failed to increase the protein level of ZBP1 after overexpressing the ADAR1 in RT112 and J82 cells. Western Blotting validation results following the overexpression of ADAR1 in RT112 and J82 cells (a, b). (c, d, e) depicted the protein levels of ADAR1 and ZBP1 following PPI treatment in RT112 and J82 cells that overexpress ADAR1. Asterisks (*) signify statistical significance between the negative control (NC) group and the overexpression (OE) ADAR1 group (*: p<0.05); the hash (#) indicates statistical significance when comparing the NC + PPI group to the OE ADAR1 + PPI group?#?P<0.05, ##?P<0.01.

PPI inhibited tumor growth in xenograft mice with bladder cancer cells

To evaluate the therapeutic effect of PPI on bladder cancer xenografts in C57BL/6J mice, the mice in each group were administered via gavage for 21 consecutive days. As shown in Figure 6a and 6b, compared with the control group, the tumor volume in the PPI treatment group was significantly reduced, while there was no statistically significant difference in body weight (P > 0.05). These results suggest that PPI has a significant inhibitory effect on bladder cancer xenografts in C57BL/6J mice, with minimal side effects on the mice’s bodies.

Figure 6 PPI Inhibited Tumor Growth in Bladder Cancer Mice. Changes in tumor volume over 21 days (a), and body weight changes in mice over 21 days (b). Asterisks (*) indicate statistical significance between the control group and the treatment group (*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01).

PPI suppressed the expression level of ADAR1 protein,while increasing the protein levels of ZBP1, RIPK3, NLRP3, Caspase-1, and GSDMD.

As illustrated in Figure 7, compared to the control group, PPI significantly suppressed the expression level of ADAR1 protein, while elevating the levels of ZBP1, RIPK3, NLRP3, Caspase-1, and GSDMD.

Figure 7 PPI suppressed ADAR1 protein expression and elevated the levels of ZBP1, RIPK3, NLRP3, Caspase-1, and GSDMD. Protein expression levels in bladder cancer mice (a,b). An asterisk (*) denotes a statistically significant difference between the control group and the drug administered group (*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01).

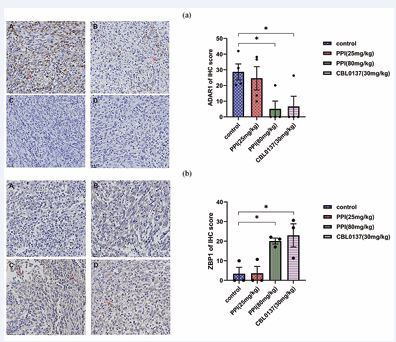

PPI inhibited ADAR1 protein expression and increased ZBP1 expression levels by IHC

As shown in Figures 8a and 8b, compared with the control group, ADAR1 exhibited a concentration dependent decrease, while the expression level of ZBP1 protein increased in a concentration-dependent manner, in the tumor tissues of Xenograft mice with bladder cancer cells.

Figure 8 PPI inhibited ADAR1 protein expression and increased ZBP1 expression levels. Immunohistochemical detection of ADAR1 and ZBP1 protein expression levels in tumor tissues of mice in each groups (a, b). A: control group; B: Low-dose PPI group; C: High-dose PPI group; D: Positive control group (CBL0137). An asterisk (*) denotes a statistically significant difference between the control group and the drug-administered group (*: p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

Bladder cancer is the second most prevalent cancer among men, following prostate cancer, with an incidence rate in males that is four times higher than in females [33]. In recent years, there has been a noted increase in the incidence of bladder cancer among women in developing countries, potentially linked to the rising prevalence of female smoking. However, at the time of diagnosis, 25% of bladder cancer patients have already experienced muscle invasion, with a 5-year survival rate of only 4.6% for those newly diagnosed each year [3-6]. Consequently, early and precise diagnosis is crucial for enhancing the success rate of cancer treatment. The standard diagnostic methods commonly employed in clinical practice, such as cystoscopy and biopsy, are invasive and may not be suitable for all patients. Moreover, these procedures can inadvertently lead to overdiagnosis, overtreatment, or undertreatment [34,35]. ZBP1, also known as the DNA-dependent activator of interferon-regulatory factors (DAI) or DLM1, plays a crucial role in the innate immune response to diseases such as viral infections and cancer [36]. This protein recognizes Z-DNA or Z-RNA through its Zα domain, which subsequently facilitates the interaction between its RHIM domain and receptor-interacting protein (RIP) kinases. This interaction is essential for regulating cellular inflammation and the interferon response to DNA/RNA from pathogens or dying cells [37]. ZBP1 can trigger the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome complex, which is associated with a form of cell death known as pyroptosis. ADAR1, on the other hand, competes with RIPK3 for binding to ZBP1, thereby inhibiting cell death and suppressing ZBP1-mediated activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and pyroptosis [17]. Consequently, targeting ADAR1 inhibition or ZBP1 activation could present innovative therapeutic avenues for cancer treatment [20,21]. In this study, we implemented a computer-aided virtual docking approach to simultaneously target ADAR1 and ZBP1, leveraging a regionally accessible library of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) compounds from Yunnan Province, China (http://www.biobiopha.com/). All TCM compounds utilized in this research were structurally validated and are documented in the PubChem small molecule database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). PPI was selected for further investigation due to its high docking score, ready availability, and previously reported anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor properties [23-25]. However, the exact anti-tumor mechanism of PPI remains to be fully elucidated. Cell viability assays demonstrated that PPI exerts a concentration- and time-dependent inhibitory effect on bladder cancer cells. It significantly downregulated ADAR1 protein expression while upregulating ZBP1 and RIPK3 protein levels. Knockdown of the ZBP1 gene abolished PPI’s ability to inhibit ADAR1 protein levels or elevate ZBP1 expression. Conversely, overexpression of the ADAR1 gene prevented PPI from upregulating ZBP1 protein levels. In vivo experiments showed that PPI markedly suppressed the growth of transplanted bladder tumors in mice, accompanied by downregulation of ADAR1 and upregulation of ZBP1, RIPK3, NLRP3, GSDMD, and Caspase-1 protein levels. Based on these findings, we hypothesize that PPI may inhibit the competitive binding of ADAR1 and RIPK3 to ZBP1, thereby activating ZBP1. This activation likely triggers the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway, enhancing pyroptosis in bladder cancer cells and ultimately inhibiting their proliferation. This study provides a preliminary exploration of the potential mechanism by which PPI inhibits the proliferation of bladder cancer cells through the regulation of the ADAR1/ZBP1 pathway. Our team intends to pursue more in-depth investigations into the mechanisms underlying PPI’s suppression of bladder cancer cell growth, with the aim of contributing to the advancement of natural drug based therapies for cancer treatment.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

ZXL, ZMT and HLZ performed the experiments; ZQW, LY and KBK analyzed the data; ZXL, RC and XNS wrote and revised the manuscript.

FUNDING

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China: [Grant Number 82060862]; Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Department-Applied Basic Research Joint Special Funds of Chinese Medicine [Grant Number 202101AZ070001-003/2019FF002( 050)/202101AZ070001-029]; Yunnan Applied Basic Research Program: [Grant Number 202301AT070098] Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Department - Kunming Medical University Joint Basic Research Program [202501AY070001-080].

REFERENCES

- De Hertogh O. Traitements de préservation vésicale pour le cancer de vessie: la thérapie trimodale, aperçu des pratiques cliniques en 2023 [Bladder preservation treatments for bladder cancer: Trimodality therapy, an overview of clinical practices in 2023]. Cancer Radiother. 2023; 27: 562-567.

- Pullen RL Jr. Bladder cancer: An Update. Nursing. 2024; 54: 27-39.

- Aginala K, Barsouk A, Aluru JS, Rawla P, Padala SA, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer. Med Sci (Basel). 2020; 8: 15.

- Wang M, Zhang Z, Li Z, Zhu Y, Xu C. E3 ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinases in bladder cancer tumorigenesis and implications for immunotherapies. Front Immunol. 2023; 14: 1226057.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018; 68: 7-30.

- Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Macdonald JS, Haller DG, Laurie JA, Tangen CM, et al. Fluorouracil plus levamisole as effective adjuvant therapy after resection of stage III colon carcinoma: a final report. Ann Intern Med. 1995; 122: 321-326.

- Racioppi M. Advances in Management of Bladder Cancer. J Clin Med. 2021; 11: 203.

- Seidl C. Targets for Therapy of Bladder Cancer. Semin Nucl Med. 2020; 50: 162-170.

- Yang F, Bettadapura SN, Smeltzer MS, Zhu H, Wang S. Pyroptosis and pyroptosis-inducing cancer drugs. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2022; 43: 2462-2473.

- Rao Z, Zhu Y, Yang P, Chen Z, Xia Y, Qiao C, et al. Pyroptosis in inflammatory diseases and cancer. Theranostics. 2022; 12: 4310-4329.

- Hao Y, Yang B, Yang J, Shi X, Yang X, Zhang D, et al. ZBP1: A Powerful Innate Immune Sensor and Double-Edged Sword in Host Immunity. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23: 10224.

- Hen XY, Dai YH, Wan XX, Hu XM, Zhao WJ, Ban XX, et al. ZBP1-Mediated Necroptosis, Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Molecules. 2022; 28: 52.

- Schwartz T, Behlke J, Lowenhaupt K, Heinemann U, Rich A. Structure of the DLM-1-Z-DNA complex reveals a conserved family of Z-DNA- binding proteins. Nat Struct Biol. 2001; 8: 761-765.

- Devos M, Tanghe G, Gilbert B, Dierick E, Verheirstraeten M, Nemegeer J, et al. Sensing of endogenous nucleic acids by ZBP1 induces keratinocyte necroptosis and skin inflammation. J Exp Med. 2020; 217: e20191913.

- Kesavardhana S, Malireddi RKS, Burton AR, Porter SN, Vogel P, Pruett- Miller SM, et al. The Zα2 domain of ZBP1 is a molecular switchregulating influenza-induced PANoptosis and perinatal lethality during development. J Bio Chem. 2020; 295: 8325-8330.

- Jiao H, Wachsmuth L, Kumari S, Schwarzer R, Lin J, Eren RO, et al. Z-nucleic-acid sensing triggers ZBP1-dependent necroptosis and inflammation. Nature. 2020; 580: 391-395.

- Yang Y, Wu M, Cao D, Yang C, Jin J, Wu L, et al. ZBP1-MLKL necroptotic signaling potentiates radiation-induced antitumor immunity via intratumoral STING pathway activation. Sci Adv. 2021; 7: eabf6290.

- Koehler H, Cotsmire S, Zhang T, Balachandran S, Upton JW, Langland J, et al. Vaccinia virus E3 prevents sensing of Z-RNA to block ZBP1- dependent necroptosis. Cell Host Microbe. 2021; 29: 1266-1276.e5.

- Karki R, Sundaram B, Sharma BR, Lee S, Malireddi RKS, Nguyen LN, et al. ADAR1 restricts ZBP1-mediated immune response and PANoptosis to promote tumorigenesis. Cell Rep. 2021; 37: 109858.

- Zhang T, Yin C, Fedorov A, Qiao L, Bao H, Beknazarov N, et al. ADAR1 masks the cancer immunotherapeutic promise of ZBP1-driven necroptosis. Nature. 2022; 606: 594-602.

- Baker AR, Slack FJ. ADAR1 and its implications in cancer development and treatment. Trends Genet. 2022; 38: 821-830.

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018; 68: 394-424.

- Wang S, Wu X, Tan M, Gong J, Tan W, Bian B, et al. Fighting fire with fire: poisonous Chinese herbal medicine for cancer therapy. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012; 140: 33-45.

- Zhong Z, Yu H, Wang S, Wang Y, Cui L. Anti-cancer effects of Rhizoma Curcumae against doxorubicin-resistant breast cancer cells. Chin Med. 2018; 13: 44.

- Shukla R, Chanda N, Zambre A, Upendran A, Katti K, Kulkarni RR, et al. Laminin receptor specific therapeutic gold nanoparticles (198AuNP- EGCg) show efficacy in treating prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012; 109: 12426-12431.

- Zhang J, Zhou F, Wu X, Zhang X, Chen Y, Zha BS, et al. Cellularpharmacokinetic mechanisms of adriamycin resistance and its modulation by 20(S)-ginsenoside Rh2 in MCF-7/Adr cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2012; 165: 120-134.

- Hsiao YT, Kuo CL, Chueh FS, Liu KC, Bau DT, Chung JG. Curcuminoids Induce Reactive Oxygen Species and Autophagy to Enhance Apoptosis in Human Oral Cancer Cells. Am J Chin Med. 2018; 46: 1145-1168.

- Wang N, Tan HY, Li L, Yuen MF, Feng Y. Berberine and Coptidis Rhizoma as potential anticancer agents: Recent updates and future perspectives. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015; 176: 35-48.

- Wang Z, Yin J, Li M, Shen J, Xiao Z, Zhao Y, et al. Combination of shikonin with paclitaxel overcomes multidrug resistance in human ovarian carcinoma cells in a P-gp-independent manner through enhanced ROS generation. Chin Med. 2019; 14: 7.

- Tian Y, Gong GY, Ma LL. Anti-cancer effects of Polyphyllin: An update in 5 years. Chemico-biological Interactions. 2020; 316: 108936

- Wang X, Zhang R, Wang S, Gu M, Li Y, Zhuang X, et al. Development, characterisation, and in vitro anti-tumor effect of self- microemulsifying drug delivery system containing polyphyllin I. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2023; 13: 356-370.

- Kuriakose T, Kanneganti TD. ZBP1: Innate Sensor Regulating Cell Death and Inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2018; 39: 123-134.

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021; 71: 209-249.

- Ng K, Stenzl A, Sharma A, Vasdev N. Urinary biomarkers in bladder cancer: A review of the current landscape and future directions. Urol Oncol. 2021; 39: 41-51.

- Repiska V, Radzo E, Biro C, Bevizova K, Bohmer D, Galbavy S. Endometrial cancer--prospective potential to make diagnostic process more specific. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2010; 31: 474-476.

- Ingram JP, Thapa RJ, Fisher A, Tummers B, Zhang T, Yin C, et al. ZBP1/DAI Drives RIPK3-Mediated Cell Death Induced by IFNs in the Absence of RIPK1. J Immunol. 2019; 203: 1348-1355.